Antiderivative (complex analysis)

In complex analysis, a branch of mathematics, the antiderivative, or primitive, of a complex-valued function g is a function whose complex derivative is g. More precisely, given an open set  in the complex plane and a function

in the complex plane and a function  the antiderivative of

the antiderivative of  is a function

is a function  that satisfies

that satisfies  .

.

As such, this concept is the complex-variable version of the antiderivative of a real-valued function.

Contents |

Uniqueness

The derivative of a constant function is zero. Therefore, any constant is an antiderivative of the zero function. If  is a connected set, then the constants are the only antiderivatives of the zero function. Otherwise, a function is an antiderivative of the zero function if and only if it is constant on each connected component of

is a connected set, then the constants are the only antiderivatives of the zero function. Otherwise, a function is an antiderivative of the zero function if and only if it is constant on each connected component of  (those constants need not be equal).

(those constants need not be equal).

This observation implies that if a function  has an antiderivative, then that antiderivative is unique up to addition of a function which is constant on each connected component of

has an antiderivative, then that antiderivative is unique up to addition of a function which is constant on each connected component of  .

.

Existence

One can characterize the existence of antiderivatives via path integrals in the complex plane, much like the case of functions of a real variable. Perhaps not surprisingly, g has an antiderivative f if and only if, for every γ path from a to b, the path integral ∫γ g(ζ) d ζ = f(b) - f(a). Equivalently, ∫γ g(ζ) d ζ = 0 for any closed path γ.

However, this formal similarity notwithstanding, possessing a complex-antiderivative is a much more restrictive condition than its real counterpart. While it is possible for a discontinuous real function to have an anti-derivative, anti-derivatives can fail to exist even for holomorphic functions of a complex variable. For example, consider the reciprocal function,  which is holomorphic on the punctured plane C\{0}. A direct calculation shows that the integral of g along any circle enlosing the origin is non-zero. So g fails the condition cited above.

which is holomorphic on the punctured plane C\{0}. A direct calculation shows that the integral of g along any circle enlosing the origin is non-zero. So g fails the condition cited above.

In fact, holomorphy is characterized by having an antiderivative locally, that is, g is holomorphic if for every z in its domain, there is some neighborhood U of z such that g has an antiderivative on U. Furthermore, holomorphy is a necessary condition for a function to have an antiderivative, since the derivative of any holomorphic function is holomorphic.

Various versions of Cauchy integral theorem, an underpinning result of Cauchy function theory, which makes heavy use of path integrals, gives sufficient conditions under which, for a holomorphic g, ∫γ g(ζ) d ζ does vanish for any closed path γ (which may be, for instance, that the domain of g be simply connected or star-convex).

Necessity

First we show that if  is an antiderivative of

is an antiderivative of  on

on  , then it has the path integral property given above. Given any piecewise C1 path

, then it has the path integral property given above. Given any piecewise C1 path ![\gamma:[a, b]\to U](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/9078483f387058616c5c969450185a37.png) , one can express the path integral of

, one can express the path integral of  over

over  as

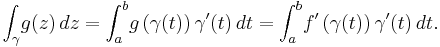

as

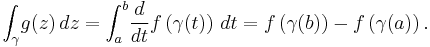

By the chain rule and the fundamental theorem of calculus one then has

Therefore the integral of  over

over  does not depend on the actual path

does not depend on the actual path  , but only on its endpoints, which is what we wanted to show.

, but only on its endpoints, which is what we wanted to show.

Sufficiency

Next we show that if g is holomorphic, and the integral of  over any path depends only on the endpoints, then g has an antiderivative. We will do so by finding an anti-derivative explicitly.

over any path depends only on the endpoints, then g has an antiderivative. We will do so by finding an anti-derivative explicitly.

Without loss of generality, we can assume that the domain  of

of  is connected, as otherwise one can prove the existence of an antiderivative on each connected component. With this assumption, fix a point

is connected, as otherwise one can prove the existence of an antiderivative on each connected component. With this assumption, fix a point  in

in  and for any

and for any  in

in  define the function

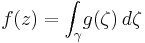

define the function

where  is any path joining

is any path joining  to

to  . Such a path exists since

. Such a path exists since  is assumed to be an open connected set. The function

is assumed to be an open connected set. The function  is well-defined because the integral depends only on the endpoints of

is well-defined because the integral depends only on the endpoints of  .

.

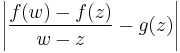

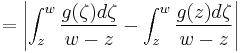

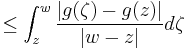

That this  is an antiderivative of

is an antiderivative of  can be argued in the same way as the real case. We have, for a given z in U,

can be argued in the same way as the real case. We have, for a given z in U,

where [z, w] denotes the line segment between z and w. By continuity of g, the final expression goes to zero as w approaches z. In other words, f' = g.

References

- Ian Stewart, David O. Tall (Mar 10, 1983). Complex Analysis. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-28763-4.

- Alan D Solomon (Jan 1, 1994). The Essentials of Complex Variables I. Research & Education Assoc. ISBN 0-87891-661-X.

![\leq \max_{ \zeta \in [w, z]} | g(\zeta) - g(z) |,](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/1d7d4865e412a8465b72b686d8b7798c.png)