Amdahl's law

Amdahl's law, also known as Amdahl's argument,[1] is named after computer architect Gene Amdahl, and is used to find the maximum expected improvement to an overall system when only part of the system is improved. It is often used in parallel computing to predict the theoretical maximum speedup using multiple processors.

The speedup of a program using multiple processors in parallel computing is limited by the time needed for the sequential fraction of the program. For example, if a program needs 20 hours using a single processor core, and a particular portion of 1 hour cannot be parallelized, while the remaining promising portion of 19 hours (95%) can be parallelized, then regardless of how many processors we devote to a parallelized execution of this program, the minimum execution time cannot be less than that critical 1 hour. Hence the speedup is limited up to 20×, as the diagram illustrates.

Contents |

Description

Amdahl's law is a model for the relationship between the expected speedup of parallelized implementations of an algorithm relative to the serial algorithm, under the assumption that the problem size remains the same when parallelized. For example, if for a given problem size a parallelized implementation of an algorithm can run 12% of the algorithm's operations arbitrarily quickly (while the remaining 88% of the operations are not parallelizable), Amdahl's law states that the maximum speedup of the parallelized version is 1/(1 – 0.12) = 1.136 times as fast as the non-parallelized implementation.

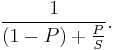

More technically, the law is concerned with the speedup achievable from an improvement to a computation that affects a proportion P of that computation where the improvement has a speedup of S. (For example, if an improvement can speed up 30% of the computation, P will be 0.3; if the improvement makes the portion affected twice as fast, S will be 2.) Amdahl's law states that the overall speedup of applying the improvement will be:

To see how this formula was derived, assume that the running time of the old computation was 1, for some unit of time. The running time of the new computation will be the length of time the unimproved fraction takes (which is 1 − P), plus the length of time the improved fraction takes. The length of time for the improved part of the computation is the length of the improved part's former running time divided by the speedup, making the length of time of the improved part P/S. The final speedup is computed by dividing the old running time by the new running time, which is what the above formula does.

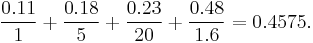

Here's another example. We are given a sequential task which is split into four consecutive parts: P1, P2, P3 and P4 with the percentages of runtime being 11%, 18%, 23% and 48% respectively. Then we are told that P1 is not sped up, so S1 = 1, while P2 is sped up 5×, P3 is sped up 20×, and P4 is sped up 1.6×. By using the formula P1/S1 + P2/S2 + P3/S3 + P4/S4, we find the new sequential running time is:

or a little less than ½ the original running time. Using the formula (P1/S1 + P2/S2 + P3/S3 + P4/S4)−1, the overall speed boost is 1 / 0.4575 = 2.186, or a little more than double the original speed. Notice how the 20× and 5× speedup don't have much effect on the overall speed when P1 (11%) is not sped up, and P4 (48%) is sped up only 1.6 times.

Parallelization

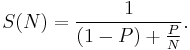

In the case of parallelization, Amdahl's law states that if P is the proportion of a program that can be made parallel (i.e. benefit from parallelization), and (1 − P) is the proportion that cannot be parallelized (remains serial), then the maximum speedup that can be achieved by using N processors is

In the limit, as N tends to infinity, the maximum speedup tends to 1 / (1 − P). In practice, performance to price ratio falls rapidly as N is increased once there is even a small component of (1 − P).

As an example, if P is 90%, then (1 − P) is 10%, and the problem can be sped up by a maximum of a factor of 10, no matter how large the value of N used. For this reason, parallel computing is only useful for either small numbers of processors, or problems with very high values of P: so-called embarrassingly parallel problems. A great part of the craft of parallel programming consists of attempting to reduce the component (1 – P) to the smallest possible value.

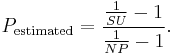

P can be estimated by using the measured speedup SU on a specific number of processors NP using

P estimated in this way can then be used in Amdahl's law to predict speedup for a different number of processors.

Relation to law of diminishing returns

Amdahl's law is often conflated with the law of diminishing returns, whereas only a special case of applying Amdahl's law demonstrates 'law of diminishing returns'. If one picks optimally (in terms of the achieved speed-up) what to improve, then one will see monotonically decreasing improvements as one improves. If, however, one picks non-optimally, after improving a sub-optimal component and moving on to improve a more optimal component, one can see an increase in return. Note that it is often rational to improve a system in an order that is "non-optimal" in this sense, given that some improvements are more difficult or consuming of development time than others.

Amdahl's law does represent the law of diminishing returns if you are considering what sort of return you get by adding more processors to a machine, if you are running a fixed-size computation that will use all available processors to their capacity. Each new processor you add to the system will add less usable power than the previous one. Each time you double the number of processors the speedup ratio will diminish, as the total throughput heads toward the limit of  .

.

This analysis neglects other potential bottlenecks such as memory bandwidth and I/O bandwidth, if they do not scale with the number of processors; however, taking into account such bottlenecks would tend to further demonstrate the diminishing returns of only adding processors.

Speedup in a sequential program

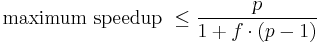

The maximum speedup in an improved sequential program, where some part was sped up  times is limited by inequality

times is limited by inequality

where  (

( ) is the fraction of time (before the improvement) spent in the part that was not improved. For example (see picture on right):

) is the fraction of time (before the improvement) spent in the part that was not improved. For example (see picture on right):

- If part B is made five times faster (

),

),  ,

,  and

and  , then

, then

- If part A is made to run twice as fast (

),

),  ,

,  and

and  , then

, then

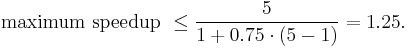

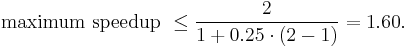

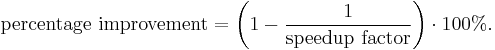

Therefore, making A twice as fast is better than making B five times faster. The percentage improvement in speed can be calculated as

- Improving part A by a factor of two will increase overall program speed by a factor of 1.6, which makes it 37.5% faster than the original computation.

- However, improving part B by a factor of five, which presumably requires more effort, will only achieve an overall speedup factor of 1.25, which makes it 20% faster.

Criticisms

Danny Hillis (in the 1998 book Pattern on the Stone) has criticized Amdahl's Law as being unnecessarily pessimistic in its assumption that the sequential portion of a program as being 5% (or 50%) of the execution time. In many applications, particularly with very large data sets (such as Google calculating PageRank, or scientific programs doing FEA), the amount of sequential code is closer to 0%, as essentially every data element can be processed independently.

John L. Gustafson pointed out in 1988 what is now known as Gustafson's Law: people typically are not interested in solving a fixed problem in the shortest possible period of time, as Amdahl's Law describes, but rather in solving the largest possible problem (e.g. the most accurate possible approximation) in a fixed "reasonable" amount of time. If the non-parallelizable portion of the problem is fixed, or grows very slowly with problem size (e.g. O(log n)), then additional processors can increase the possible problem size without limit.

See also

- Amdahl Corporation

- Brooks's law

- Gustafson's law

- Karp–Flatt metric

- Moore's law

- Ninety-ninety rule

- Speedup

Notes

- ^ Rodgers 85, p.226

References

- Amdahl, Gene (1967). "Validity of the Single Processor Approach to Achieving Large-Scale Computing Capabilities" (PDF). AFIPS Conference Proceedings (30): 483–485. http://www-inst.eecs.berkeley.edu/~n252/paper/Amdahl.pdf.

- Rodgers, David P. (June 1985). "Improvements in multiprocessor system design". ACM SIGARCH Computer Architecture News archive (New York, NY, USA: ACM) 13 (3): 225–231. doi:10.1145/327070.327215. ISSN 0163-5964. http://portal.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=327215.

External links

- Cases where Amdahl's law is inapplicable

- Oral history interview with Gene M. Amdahl Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota. Amdahl discusses his graduate work at the University of Wisconsin and his design of WISC. Discusses his role in the design of several computers for IBM including the STRETCH, IBM 701, and IBM 704. He discusses his work with Nathaniel Rochester and IBM's management of the design process. Mentions work with Ramo-Wooldridge, Aeronutronic, and Computer Sciences Corporation

- Reevaluating Amdahl's Law

- Reevaluating Amdahl's Law and Gustafson's Law

- A simple interactive Amdahl's Law calculator

- "Amdahl's Law" by Joel F. Klein, Wolfram Demonstrations Project, 2007.

- Amdahl's Law in the Multicore Era

- Amdahl's Law explanation

- Blog Post: "What the $#@! is Parallelism, Anyhow?"

- Amdahl's Law applied to OS system calls on multicore CPU

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||