Ambisonics

Ambisonics (not to be confused with ambiophonics) is a series of recording and replay techniques using multichannel mixing technology that can be used live or in the studio. By encoding and decoding sound information on a number of channels, a 2-dimensional ("planar", or horizontal-only) or 3-dimensional ("periphonic[1]", or full-sphere) sound field can be presented. Ambisonics was invented by Michael Gerzon of the Mathematical Institute, Oxford, who – with Professor Peter Fellgett[2] of the University of Reading, David Brown, John Wright and John Hayes of the now defunct IMF Electronics, and building on the work of other researchers – developed the theoretical and practical aspects of the system in the early 1970s.

Contents |

Advantages

Ambisonics offers a number of advantages over other surround sound systems:

- It is isotropic in that sounds arriving from all directions are treated equally (as opposed to most other surround systems that assume that the main sources of sound are frontal and that rear channels are only for ambience or special effects).

- All speakers are generally used to localise a sound in any direction (as opposed to conventional pan-potted (pair-wise mixing) techniques which use only two adjacent speakers). This gives better localisation, particularly to the sides and rear.[3][4]

- The stability and imaging of the reproduced soundfield vary less with listener position than with most other surround systems. The soundfield can even be appreciated by listeners outside the speaker array.[5]

- A minimum of four channels of information are required for distribution and storage of a full-sphere soundfield, and three for a horizontal soundfield. (This is fewer than other surround systems). Full-sphere replay requires a minimum of six loudspeakers (a minimum of four for horizontal), the signal for each speaker position being derived using appropriate circuitry or software.

- The loudspeakers do not have to be positioned in a rigid setting; most regular polygons and (with somewhat more complex technology) a number of irregular figures can be accommodated. This allows the speaker configuration to be matched more closely to real listening environments, such as domestic living rooms.

- The Ambisonic signal is independent of the replay-system: the same signal can be decoded for varying numbers of loudspeakers (in general, the more speakers, the higher the accuracy of the reconstructed soundfield). This allows flexibility for composers, performers and production teams to produce a "final" mix without worrying about how the mix will later be released and decoded.

Disadvantages

Ambisonics also suffers from some disadvantages:

- It is not supported by any major record label or media company.

- It has never been well marketed and, largely as a result, is not widely known.

- It can be conceptually difficult for people to grasp (as opposed to conventional "one channel=one speaker" surround, which is easier).

- It requires an Ambisonic decoder box at the replay end, and there are few commercial decoder manufacturers. However, G-Format ameliorates this (with attendant benefits and drawbacks), and there is a growing collection of free Ambisonic software decoders.

- The minimum number of loudspeakers required for planar (horizontal) decoding is four. While this is satisfactory in the average sized living-room for which it was designed, if the listening area is too large then, without treatment, the resulting soundfield can approach the limits of stability. This has resulted in some unimpressive demos. A six-speaker horizontal array is more stable.

- The two-channel matrixed form of Ambisonics, 2-channel UHJ, is not comparable to "true multichannel" (discrete) surround distribution systems. While multichannel distribution formats for Ambisonics exist (such as B-Format, G-Format and 2½ to 4 channel UHJ), only 2-channel UHJ and, to a lesser extent, G-Format have been employed in commercial releases to date.

First-order Ambisonics and B-Format

In the basic version, known as first-order Ambisonics, sound information is encoded into four channels: W, X, Y and Z. This is called Ambisonic B-format. The W channel is the non-directional mono component of the signal, corresponding to the output of an omnidirectional microphone. The X, Y and Z channels are the directional components in three dimensions. They correspond to the outputs of three figure-of-eight microphones, facing forward, to the left, and upward respectively. (Note that the fact that B-format channels are analogous to microphone configurations does not mean that Ambisonic recordings can only be made with coincident microphone arrays.)

The B-format signals are based on a spherical harmonic decomposition of the soundfield and correspond to the sound pressure (W), and the three components of the pressure gradient (X, Y, and Z) (not to be confused with the related particle velocity) at a point in space. Together, these approximate the sound field on a sphere around the microphone; formally the first-order truncation of the multipole expansion. This is called "first-order" because W (the mono signal) is the zero-order information, corresponding to a sphere (constant function on the sphere), while X, Y, and Z are the first-order terms (the dipoles), corresponding to the response of figure-of-eight microphones – as functions, to particular functions that are positive on half the sphere, and negative of the other half. This first-order truncation is only an approximation of the overall sound field (but see Higher-order Ambisonics).

The loudspeaker signals are derived by using a linear combination of these four channels, where each signal is dependent on the actual position of the speaker in relation to the center of an imaginary sphere the surface of which passes through all available speakers. In more advanced decoding schemes, spatial equalization is applied to the signals to account for the differences in the high- and low-frequency sound localization mechanisms in human hearing. A further refinement accounts for the distance of the listener from the loudspeakers.

Decoding

Several different decoder designs are possible, with different advantages and disadvantages. They use different decoding equations, and are intended for different types of application. Hardware decoders have been commercially available since the late 1970s; currently, Ambisonics is standard in surround products offered by Meridian Audio, Ltd.. Ad hoc software decoders are also available (see Downloadable B-Format files).

Relationship to coincident stereo techniques

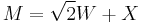

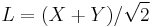

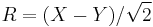

Different linear combinations of W, X, Y and Z can create signals equivalent to those picked up by any conventional microphone (omnidirectional, cardioid, hypercardioid, etc.) pointing in any direction. Thus the signals used in any coincident stereo microphone technique can be generated directly from the B-format signals (for example, Blumlein Mid-Side with a forward-facing cardioid using  and

and  , or a Blumlein Pair using

, or a Blumlein Pair using  and

and  ).

).

Thus we can consider first-order B Format as a series of sum and difference channels:

- W = front + back + left + right + up + down (mono, omni mic)

- X = front − back (figure-of-eight mic facing forward)

- Y = left − right (figure-of-eight facing left)

- and Z = up − down (figure-of-eight facing up).

Downloadable B-Format files

An official file format for B-Format files, called ".amb" format, has been defined. Over two hundred such files are available for free download from Ambisonia.com. The website also gives details of software players.

The ".amb" file format is defined for B-Format files up to third-order, full-sphere (16 channels), although most of the files currently available are first-order, full-sphere (4 channels).

Recording techniques

See also.[6]

The soundfield microphone

Many Ambisonic recordings have been made using a special microphone – the soundfield microphone (SFM). This microphone has also become popular with recording engineers, since it can be reconfigured electronically or via software to provide different stereo and 3-D polar responses either during or after recording.

"Native" microphones

The SFM uses a tetrahedral array of capsules, the outputs of which are matrixed together to generate the component B-Format signals. However it is entirely practical to generate B-Format from a collection of coincident microphones (or mic capsules), each with the characteristics of one of the B-Format channels listed earlier. This is referred to as a "Native" Ambisonic microphone or microphone array. The primary difficulty inherent in this approach is that high-frequency localisation relies on the diaphragms approaching true coincidence, and this is difficult to achieve with complete microphones. However electronic coincidence compensation can be used, and this can be effective especially where small capsules and not whole microphones are employed.

Thus if you wish to generate planar B-Format (WXY), you could use an omnidirectional mic coincident with a forward-facing and a left-facing figure-of-eight. Exactly this technique was used by Dr Jonathan Halliday at Nimbus Records to record their extensive and continuing series of Ambisonic releases.

Ambisonic mixing

A popular and unfortunate misconception is that Ambisonic recordings can only be made with the SFM, and as a result there is a widespread, and erroneous, belief that Ambisonics can only be used to capture a live acoustic event (something that accounts for a tiny proportion of modern commercial recordings, the vast majority of which are built up in the studio and mixed from multitrack). This is not the case. In fact, Michael Gerzon's designs for Ambisonic panpots pre-date much of his work on soundfield microphone technology. Ambisonic panpots - which allow mono (for example) signals to be localised in B-Format space - were developed as early as the 1970s, and were incorporated into a special mixing console designed by Chris Daubney[7] at the IBA (UK Independent Broadcasting Authority) and built by Alice Stancoil Ltd in the early 1980s for the IBA surround-sound test broadcasts.

Ambisonic panpots, with differing degrees of sophistication, provide the fundamental additional studio tool required to create an Ambisonic mix, by making it possible to localise individual, conventionally-recorded multi-track or multi-mic sources around a 360° stage analogous to the way conventional stereo panpots localise sounds across a front stage. However, unlike stereo panpots, which traditionally vary only the level between two channels, Ambisonic panning provides additional cues which eliminate conventional localisation accuracy problems. This is especially pertinent to surround, where our ability to localise level-only panned sources is severely limited to the sides and rear.

Other tools included "spreaders" which were designed to "de-localise" a signal (typically by varying the virtual source angle with frequency within a determined range) – for example, in the case of reverb returns – however these were not developed further.

Legacy hardware

By the early 1980s, studio hardware existed for the creation of multitrack-sourced, Ambisonically-mixed content, including the ability to incorporate SFM-derived sources (for example for room ambience) into a multichannel mix.[8] This was thanks primarily to the efforts of Dr Geoffrey Barton (now of Trifield Productions) and the pro-audio manufacturers Audio & Design Recording, UK (now Audio & Design Reading Ltd). Barton designed a suite of outboard rack-mounted studio units that became known as the Ambisonic Mastering System.[9] These units were patched into a conventional mixing console and allowed conventional multitrack recordings to be mixed Ambisonically. The system consisted of four units:

- Pan-Rotate Unit - This enabled eight mono signals to be panned in B-format, including 360° "angle" control and a "radius vector" control allowing the source to be brought in towards the centre, plus a control to rotate an external or internal B-format signal.

- B-Format Converter - This connected to four groups and an aux send and allowed existing console panpots to pan across a B-Format quadrant.

- UHJ Transcoder - This both encoded B-Format into 2-channel UHJ (see UHJ Format) and in addition allowed a stereo front stage and a stereo rear stage (both with adjustable widths) to be transcoded direct to 2-channel UHJ.

- Ambisonic Decoder - this accepted both horizontal (WXY) B-format and 2-channel UHJ and decoded it to four speaker feeds with configurable array geometry.

It is understood that versions of these units were subsequently made available in the late 1990s by Cepiar Ltd along with some other Ambisonics hardware. It is not known if they are still currently available.

A significant number of releases were made with this equipment, all in 2-channel UHJ, including several albums on the KPM production music library label, and commercial releases such as Steve Hackett's Till We Have Faces, The Alan Parsons Project's Stereotomy, Paul McCartney's Liverpool Oratorio, Frank Perry's Zodiac, a series of albums on the Collins Classics label, and others, most of which are available on CD. See The Ambisonic Discography in the External links for more information. Engineer John Timperley employed a transcoder on virtually all his mixes over the course of over a dozen years until his death in 2006. Unfortunately the albums, film soundtracks and other projects he created in UHJ over this period are largely undocumented at present, and thus remain unlisted in the Discography.

The lack of availability of 4-track mastering equipment led to a tendency (now regretted by some of the people involved) to mix directly to 2-channel UHJ rather than recording B-format and then converting it to UHJ for release. The fact that you could mix direct to 2-channel UHJ with nothing more than the transcoder made this even more tempting. As a result there is a lack of legacy Ambisonically-mixed B-format recordings that could be released today in more advanced formats (such as G-Format). However, the remastering – and in some cases release – of original 2-channel UHJ recordings in G-Format has proved to be surprisingly effective, yielding results at least as good as the original studio playbacks, thanks primarily to the significantly higher quality of current decoding systems (such as file-based software decoders) compared to those available when the recordings were made.

Current mixing tools

The advent of digital audio workstations has led to the development of both encoding and decoding tools for Ambisonic production. Many of these have been developed under the auspices of the University of York (see External links). The vast majority to date have been created using the VST plugin standard developed by Steinberg and used widely in a number of commercial and other software-based audio production systems, notably Steinberg's Nuendo. With the lack of necessity to interface to a conventional console, the encoding tools have primarily taken the form of B-Format panpots and associated controls. Decoder plugins are available for monitoring.

There are presently some issues with implementing B-format groups and other channel structures in current DAW software which is often either stereo-based or based inflexibly on conventional surround configurations. The ability must exist to use plugins with one input and multiple outputs, for example, and it must be possible to create B-format buses of some sort and hook up decoder plugins to them, record their contents, and perform other operations. Documentation is being assembled to assist engineers wishing to work with these tools.

There are also stand-alone software tools for manipulating multichannel files and for offline decoding of B-Format and UHJ files to standard arrays, plus software players capable of playing and decoding standard B-Format files and other Ambisonic content.

The plugin field is a particular growth area for Ambisonic production tools at the present time.

UHJ format

UHJ is a development of Ambisonics designed to allow Ambisonic recordings to be carried by mono- and stereo-compatible media. It is a hierarchy of systems in which the recorded soundfield will be reproduced with a degree of accuracy that varies according to the available channels. Although UHJ permits the use of up to four channels (carrying full-sphere with-height surround), only the 2-channel variant is in current use (as it is compatible with currently-available 2-channel media). 2-channel UHJ does not include height information and decodes to provide a horizontal surround experience to a somewhat lower level of resolution than 2½- or 3-channel UHJ.

Super stereo

A feature of domestic Ambisonic decoders has been the inclusion of a super stereo feature. This allows conventional stereo signals to be "wrapped around" the listener, using some of the capabilities of the decoder. A control is provided that allows the width to be varied between mono-like and full surround. This provides a useful capability for a listener to get more from their existing stereo collection.

A different kind of "super stereo" is experienced by listeners to a 2-channel UHJ signal who are not using a decoder. Because of the inter-channel phase relationships inherent in the encoding scheme, the listener experiences stereo that is often significantly wider than the loudspeakers. It is also often more stable and offers superior imaging.

Both features were used as selling points in the early days of Ambisonics, and especially Ambisonic mixing. It helped to overcome a "chicken and egg" situation where record companies were reluctant to release Ambisonic recordings because there were few decoders in the marketplace, while hi-fi manufacturers were unwilling to licence and incorporate Ambisonic decoders in their equipment because there was not very much mainstream released content. On the one hand, it was worth having a decoder because you could get more out of your existing record collection; while on the other it was worth making Ambisonic recordings because even people without a decoder could gain appreciable benefits.

G-Format

The lack of availability of Ambisonic decoders (only a handful of hardware decoder models are currently available, although software-based players are now emerging) led to the proposal that Ambisonics could be distributed by decoding the original signal (preferably B-Format but also legacy 2-channel UHJ recordings) in the studio instead of at the listening end. A professional software or hardware-based decoder is used to decode the Ambisonic signal to a conventional surround speaker array (e.g. 5.1) and the resulting speaker feeds are authored to a conventional multichannel disc medium such as DVD. This is known as "G-Format".[10]

The obvious advantage of this approach is that any surround listener can be able to experience Ambisonics; no special decoder is required beyond that found in a common home theatre system. The main disadvantage is that the flexibility of rendering a single, standard Ambisonic signal to any target speaker array is lost: the signal is targeted towards a specific "standard" array and anyone listening with a different array may experience a degradation of localisation accuracy, depending on how much the actual array differs from the target.

In practice, Ambisonics in general has proved to be very robust, however. Examples of G-Format recently released by Nimbus Records used 2-channel UHJ decoded to a square array of four speakers (this is conventional for decoding planar Ambisonic recordings; a rectangle of sides with ratios of between 2:1 and 1:2 can be used, a square being midway between the two). The resulting 4-channel (LF, RF, LS, RS) signal was authored to DVD-Audio/Video discs and although many listeners will be listening on arrays other than a square, the results have proved very encouraging.

Some releases of G-format sourced from B-Format have also occurred, for example the album Swing Live by Bucky Pizzarelli (available on Chesky Records, DVD-A or SACD), where a B-Format SFM recording was "manually decoded" to 4.0 speaker feeds in the mixdown process.

Recovering B-Format from G-Format

It is theoretically possible to recover B-Format from a G-Format signal, in which case Ambisonic listeners with their own decoders could recover the B-Format and decode it for their own array, thus achieving more accurate localisation. However for the greatest accuracy in smaller environments such as a living room, the decode process includes shelf filtering that may cause the decode to be irreversible if the shelf-filters are non-linear. It should be possible to implement linear shelf-filtering when decoding to a rectangular or regular polygonal array, but more work has yet to be performed in this area.

It is also possible that as a result of current development work (primarily by Dr Peter Craven) on hierarchical systems for audio rendering, these problems can be overcome (and G-Format superseded) by distributing a common signal that plays back as 5.1 on 5.1 systems (and so on) but can also be decoded Ambisonically if listeners have the right equipment.[11]

G-Format with height

It is entirely possible to create G-Format recordings that include height information. However, while there are "standards" for conventional planar surround (5.1, 7.1, etc.) there is currently no recognised standard (apart from Ambisonics) for the inclusion of height. There are several techniques being used, the most common one being to take one or two channels of the 5.1 signal (typically LFE, or CF & LFE) and to use them to drive elevated loudspeaker(s). It would be possible to decode an Ambisonic full-sphere recording to configurations like this, and to release the result (which would then be G-Format).

Current developments

General

The Ogg Vorbis project has shown interest in implementing Ambisonics as a means for including surround sound in their project. In addition there is a growing series of freely-available developments such as VST plugins, enabling common DAW systems (such as Nuendo) to be used to encode and decode B-Format and generate decoded speaker feeds; see External links.

Higher-order Ambisonics

A particularly active area of current research is the development of "higher orders" of Ambisonics. These use more channels than the original first-order B-Format to capture significantly more spatial information. At present, "real" recording techniques using them are in their infancy, it is, however, straightforward to compose synthetic recordings. Benefits include greater localisation accuracy and better performance in large-scale replay environments such as performance spaces.

The higher orders correspond to further terms of the multipole expansion of a function on the sphere in terms of spherical harmonics. As discussed at wave field synthesis, in the absence of obstacles, sound in a space over time can be described as the pressure at a plane or over a sphere – and thus if one reproduces this function, one can reproduce the sound of a microphone at any point in the space pointing in any direction.

Possible combinations

The following table lists the various higher-order combinations which are possible. In theory, the table could be extended to infinity.

In the table, note that as you move from horizontal to full-sphere, or from lower to higher orders, backwards compatibility is always guaranteed because channels are only ever added. This means, for example, that a first-order, horizontal decoder can still decode a third-order, full-sphere soundfield by simply ignoring 13 of the 16 channels.

| Horizontal order | Height order | Soundfield type | Number of channels |

Channels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | horizontal | 3 | WXY |

| 1 | 1 | full-sphere | 4 | WXYZ |

| 2 | 0 | horizontal | 5 | WXYUV |

| 2 | 1 | mixed-order | 6 | WXYZUV |

| 2 | 2 | full-sphere | 9 | WXYZRSTUV |

| 3 | 0 | horizontal | 7 | WXYUVPQ |

| 3 | 1 | mixed-order | 8 | WXYZUVPQ |

| 3 | 2 | mixed-order | 11 | WXYZRSTUVPQ |

| 3 | 3 | full-sphere | 16 | WXYZRSTUVKLMNOPQ |

Microphones and decoders

Soundfield microphones for recording first-order B-Format have been commercially available for many decades. A mic which can record up to third-order is shipping.[12] First-order B-Format decoders have been commercially available since the late 1970s. Ad hoc second-order and third-order software players (decoders) are currently available (see Downloadable B-Format files).

Use in gaming

Higher-order Ambisonics has found a niche market in video games developed by Codemasters. Their first game to use an Ambisonic audio engine was Colin McRae: DiRT, however, this only used Ambisonics on the PlayStation 3 platform.[13] Their game Race Driver: GRID extended the use of Ambisonics to the Xbox 360 platform,[14] and Colin McRae: DiRT 2 uses Ambisonics on all platforms including the PC.[15] The recent game from Codemasters, F1 2010, uses fourth-order Ambisonics on faster PCs. The PC versions use Blue Ripple Sound's Rapture3D OpenAL driver.

| B-Format channel |

Weight |

|---|---|

| W |  |

| X |  |

| Y |  |

| Z |  |

| R |  |

| S |  |

| T |  |

| U |  |

| V |  |

| K |  |

| L |  |

| M |  |

| N |  |

| O |  |

| P |  |

| Q |  |

Furse-Malham higher-order format

Furse-Malham higher-order format (FMH-Format) is a set of coefficients that can be applied to the first 16 B-format channels. The FMH set of coefficients applies weightings to the channels such that all the spherical harmonic coefficients have a maximum value of unity. Whilst this approach is not rigorously "correct" in mathematical terms, it has significant engineering advantages in that it restricts the maximum levels a panned mono source will generate in some of the higher-order channels.[16]

The Furse-Malham set of weighting factors is part of the ".amb" specification for downloadable B-Format files.

Patents and Trademarks

Most of the patents covering Ambisonic developments have now expired (including those covering the Soundfield microphone) and, as a result, the basic technology is available for anyone to implement. Exceptions to this include Dr Geoffrey Barton's Trifield technology, which is a three-speaker stereo rendering system based on Ambisonic theory (US 5594800), and so-called "Vienna" decoders, based on Gerzon and Barton's Vienna 1992 AES paper, which are intended for decoding to irregular speaker arrays (US 5757927).

The "pool" of patents comprising Ambisonics technology was originally assembled by the UK Government's National Research & Development Corporation (NRDC), which existed until the late 1970s to develop and promote British inventions and license them to commercial manufacturers - ideally to a single licensee. The system was ultimately licensed to Nimbus Records (now owned by Wyastone Estate Ltd) who hold the rights to the "interlocking circles" Ambisonic logo (UK trademarks 1113276 and 1113277), and the text marks "AMBISONIC" and "A M B I S O N" (UK trademarks 1500177 and 1112259).

Note that applications to register the word marks (trademarks) "AMBISONICS" and "AMBISONIC" in the USA were abandoned in 1992 and 2009 (US trademark serial numbers 74118119 and 77695983).

Notes on nomenclature

Some terms: their meanings and usage

Michael Gerzon used to wryly comment on the fact that the term "quadraphonic" mixed Greek and Latin roots (it is a hybrid word), and that it should have properly been called "tetraphony" or "quadrasonics" (you could also call it "quadrifontal" – "four-source"). The term "ambisonics" (literally "surround sound") does not suffer from this mongrel heritage.

In Ambisonics the term "periphony" (literally, "sound (around) the edge") is frequently used to denote full-sphere, with-height, 3-dimensional surround – note that in a periphonic system virtual sources can be localised anywhere within the sphere, not only at its surface.

Strictly speaking, we should define a difference between "with-height" and "periphony". The former implies the ability to (re)create a sensation of sounds coming from above the listener, and/or a sensation of space above the listener. "Periphony", however, strictly denotes full-sphere reproduction, which includes height and depth, providing the ability to place sounds in any direction including below the plane of the listener.

Thus a system for replaying height information might utilise a set of four speakers at ear level, say, and another four directly above them and higher up ("stacked rectangles"). This would be able to reproduce height, but not "depth". An array of "crossed rectangles", however (a horizontal rectangle at ear height and a vertical rectangle crossing it at right-angles at the centre, with two speakers at floor level and two more directly above them, above the plane of the horizontal rectangle), would permit the reproduction of depth as well as height. It is widely believed that when Michael Gerzon referred to "periphony" he meant the latter capability, as does Peter Craven, and not solely the ability to reproduce height.

The term "planar" (on a single plane, i.e. no height, or 2-dimensional) is used to refer to horizontal-only Ambisonics; the term "pantophonic" will also be found with the same meaning.

Also, in this field; "2-D" and "3-D" respectively mean planar & periphonic. It is not defined as "stereo", "5.1", etc...

Compass points

A significant difference between Ambisonics and other surround systems is that the signal is the same irrespective of the number of speakers connected to the decoder, or where they are. The decoder and speaker array do their best to render the original soundfield to the highest resolution of which the system is capable. Sound is not drawn into the speakers and you may not know where the speakers are (and it doesn't matter).

Conventional surround, however, maps one speaker to one channel. Thus each speaker (or channel) has a name based on its physical location (such as "left rear" or "right front"). In Ambisonics, it doesn't matter where the speakers are, it's the direction that's important, and the fact that the speakers are all required and working together to localise virtual sources. So we may talk about a source coming from so many degrees from centre front, and often reference is made in terms of compass points, centre front being North.

Thus while a typical surround "walk-around" or channel identification test will simply drive each speaker in turn and label the speaker from which listeners should be hearing sound, the Ambisonic equivalent will often call out compass directions, so listeners can check that the virtual source really is coming from that direction. How the points of a periphonic "fly-around" would be labelled is another matter entirely.

See also

- Ambisonic decoding

- Ambisonic UHJ Format

- Colin McRae: DiRT, a video game whose PlayStation 3 version uses Ambisonics

- Colin McRae: DiRT 2, a video game which uses Ambisonics (all versions)

- F1 2010, a video game which uses Ambisonics (all versions)

- Meridian Audio, Ltd.

- Nimbus Records

- Race Driver: GRID, a video game whose PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 versions use Ambisonics

- Soundfield microphone

- Surround sound

- Trifield

References

- ^ Michael A. Gerzon, Periphony: With-Height Sound Reproduction. Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, 1973, 21(1):2–10.

- ^ Peter Fellgett, Ambisonics. Part One: General System Description, Studio Sound, August 1975, 1:20–22,40.

- ^ Gerzon, Michael (December 8, 1977). "Don't say quad - say psychoacoustics". New Scientist 76: 634–636.

- ^ Leese, Martin (2005-02-06). "References on Pair-wise Mixing". An Experiment into Pair-Wise Mixing and Channel Separation. http://members.tripod.com/martin_leese/Ambisonic/exper.html#REFERENCES. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ^ Malham, DG (1992). "Experience with Large Area 3-D Ambisonic Sound Systems" (PDF). Proceedings of the Institute of Acoustics 14 (5): 209–215. http://www.dmalham.freeserve.co.uk/ioapaper1.pdf. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ^ Michael A. Gerzon, Ambisonics. Part Two: Studio Techniques, Studio Sound, October 1975, pages 24–30. Correction in Oct. 1975 issue on page 60.

- ^ Chris Daubney, Ambisonics – an operational insight. Studio Sound, Aug. 1982, pp.52–58

- ^ Richard Elen, Ambisonic mixing - an introduction, Studio Sound, September 1983

- ^ Michael A Gerzon and Geoffrey J. Barton, Ambisonic Surround-Sound Mixing for Multitrack Studios, AES Preprint C1009, Convention 2i (April 1984)(AES E-Library location: (CD aes10) /pp8185/pp8405/9109.pdf)

- ^ Richard Elen, Ambisonics for the New Millennium, September 1998.

- ^ Craven, Peter G.; Malcome J. Law, J. Robert Stuart, Rhonda J. Wilson (June 2003). "Hierarchical Lossless Transmission of Surround Sound Using MLP". Proceedings of the AES 24th International Conference: Multichannel Audio, The New Reality. AES 24th International Conference. AES.

- ^ "em32 Eigenmike microphone array". http://www.mhacoustics.com/page/page/2949006.htm. Retrieved 2008-10-18. "We are currently shipping em32 arrays with spatial harmonic orders up to and including third-order."

- ^ Deleflie, Etienne (August 30, 2007). "Interview with Simon Goodwin of Codemasters on the PS3 game DiRT and Ambisonics.". Building Ambisonia.com. Australia: Etienne Deleflie. http://etiennedeleflie.net/2007/08/30/interview-with-simon-goodwin-of-codemasters-on-the-ps3-game-dirt-and-ambisonics/. Retrieved August 07, 2010.

- ^ Deleflie, Etienne (June 24, 2008). "Codemasters ups Ambisonics again on Race Driver GRID …". Building Ambisonia.com. Australia: Etienne Deleflie. http://etiennedeleflie.net/2008/06/24/codemasters-ups-their-useage-of-ambisonics-on-race-driver-grid/. Retrieved August 07, 2010.

- ^ Firshman, Ben (3 March 2010). "Interview: Simon N Goodwin, Codemasters". The Boar (Coventry, United Kingdom: The University of Warwick): p. 18. Core of Volume 32, Issue 11. http://theboar.org/games/2010/mar/3/interview-simon-goodwin-codemasters/. Retrieved 7 August 2010.

- ^ Malham, David (April 2003). "Higher order Ambisonic systems" (PDF). Space in Music - Music in Space (Mphil thesis). University of York. pp. 2–3. http://www.york.ac.uk/inst/mustech/3d_audio/higher_order_ambisonics.pdf. Retrieved 2007-11-02.

Source texts on Ambisonics - basic theory

Included with permission from the List of Ambisonic Publications, which contains an extended list of references not all included here.

- Duane H. Cooper, Takeo Shiga: Discrete-matrix multichannel stereo, JAES, June 1972, Vol.20, No:5

- Michael Gerzon: Periphony: With-height sound reproduction, JAES Jan/Feb. 1973, Vol.21, No:1

- Michael Gerzon: Surround-sound psychoacoustics, Criteria for the design of matrix and discrete surround-sound systems. Wireless World, December 1974, pp. 483–485.

- Peter Fellgett: Ambisonics. Part One: General system description. Studio Sound, August 1975, p. 20-40.

- Michael Gerzon: Compatible 2-channel encoding of surround sound. NRDC reprint from Electronics Letters 11th Dec. 1975 Vol.11 Nos: 25/26.

- Michael Gerzon: Multidirectional sound reproduction systems, US Patent 3,997,725. Dec. 14, 1976

- Michael Gerzon: The optimum choice of surround sound specification. AES preprint No:1199, March 1977.

- Michael Gerzon: NRDC surround sound system. Wireless World, April 1977, p. 36-39.

- Michael Gerzon: Criteria for evaluating surround sound systems. JAES June 1977, Vol 25, No:6, p. 400-408.

- Peter Craven, Michael Gerzon: Coincident microphone simulation covering three dimensional space and yielding various directional outputs, US Patent 4,042,779. Aug. 16, 1977

- Michael Gerzon: Sound reproductions systems with augmentation of image definition in a selected direction, US Patent 4,081,606. March 28, 1978

- Michael Gerzon: Sound reproduction system with non-square loudspeaker lay-out, US Patent 4,086,433. Apr. 25, 1978

- Michael Gerzon: Non-rotationally-symmetric surround-sound encoding system, US Patent 4,095,049. June 13, 1978

- Barry Fox (writing as Adrian Hope): Surround sound patents, will the future of surround sound depend on patent bargaining? Wireless World, Jan 1979, p. 57-58.

- Michael Gerzon: Sound reproduction system with matrixing of power amplifier outputs, US Patent 4,139,729. Feb. 13, 1979

- Michael Gerzon: Sound reproduction systems, US Patent 4,151,369. Apr. 24, 1979

- Barry Fox (writing as Adrian Hope): Ambisonics - The theory and patents. Studio Sound, Oct 1979, p. 36-44.

- Michael Gerzon: Practical periphony: The reproduction of full-sphere sound, AES Preprint 1571, London 1980

- Michael Gerzon: Decoders for feeding irregular loudspeaker arrays, US Patent 4,414,430. Nov. 8, 1983

- Michael Gerzon: Ambisonics in multichannel broadcasting and video. JAES Vol 33, No:11, Nov. 1985 p. 859-871.

- Dermot J. Furlong: Comparative study of effective soundfield reconstruction. AES preprint 2842, Oct. 18-21, 1989.

- Michael Gerzon: Hierarchical system of surround sound transmission for HDTV, AES Preprint 3339, Vienna 1992

- Michael Gerzon: Ambisonic decoders for HDTV, AES Preprint 3345, Vienna 1992

- W.C.Clarck, K.Alimi, B.Spendor: Ambisonic depending Aural recognition, International Institute of Inuitive Audio research, IIAR 1205, pp 15–32, May 2008

External links

- Ambisonic.net website

- Ambisonic Surround Sound FAQ

- Ambisonia, a repository of Ambisonic recordings and compositions

- Ambisonic Discography, a list of record releases, broadcasts and other Ambisonic content

- Ambisonics Wiki on Ambisonia, a knowledge base for documenting and sharing anything related to Ambisonics

- List of Ambisonic Publications, an extensive list of published references and commentaries

- Ambisonics resources at the University of Parma

- 3D Audio Links and Information

- Ambisonic resources at the University of York

- Why First-order Ambisonics doesn’t work

- Why Ambisonics Works, a short critique of the above

- Josephson Engineering, who manufacture a "native" B-Format mic, the C700S