Algorithmic Lovász local lemma

In theoretical computer science, the algorithmic Lovász local lemma gives an algorithmic way of constructing objects that obey a system of constraints with limited dependence.

Given a finite set of bad events  in a probability space with limited dependence amongst the

in a probability space with limited dependence amongst the  's and with specific bounds on their respective probabilities, the Lovász local lemma proves that with non-zero probability all of these events can be avoided. However, the lemma is non-constructive in that it does not provide any insight on how to avoid the bad events.

's and with specific bounds on their respective probabilities, the Lovász local lemma proves that with non-zero probability all of these events can be avoided. However, the lemma is non-constructive in that it does not provide any insight on how to avoid the bad events.

If the events  are determined by a finite collection of mutually independent random variables, a simple Las Vegas algorithm with expected polynomial runtime proposed by Robin Moser and Gábor Tardos[1] can compute an assignment to the random variables such that all events are avoided.

are determined by a finite collection of mutually independent random variables, a simple Las Vegas algorithm with expected polynomial runtime proposed by Robin Moser and Gábor Tardos[1] can compute an assignment to the random variables such that all events are avoided.

Contents |

Review of Lovász local lemma

The Lovász Local Lemma is a powerful tool commonly used in the probabilistic method to prove the existence of certain complex mathematical objects with a set of prescribed features. A typical proof proceeds by operating on the complex object in a random manner and uses the Lovász Local Lemma to bound the probability that any of the features is missing. The absence of a feature is considered a bad event and if it can be shown that all such bad events can be avoided simultaneously with non-zero probability, the existence follows. The lemma itself reads as follows:

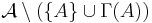

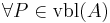

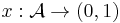

Let  be a finite set of events in the probability space

be a finite set of events in the probability space  . For

. For  let

let  denote a subset of

denote a subset of  such that

such that  is independent from the collection of events

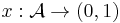

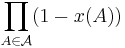

is independent from the collection of events  . If there exists an assignment of reals

. If there exists an assignment of reals  to the events such that

to the events such that

then the probability of avoiding all events in  is positive, in particular

is positive, in particular

Algorithmic version of the Lovász local lemma

The Lovász Local Lemma is non-constructive because it only allows us to conclude the existence of structural properties or complex objects but does not indicate how these can be found or constructed efficiently in practice. Note that random sampling from the probability space  is likely to be inefficient, since the probability of the event of interest

is likely to be inefficient, since the probability of the event of interest ![Pr\left[\overline{A_1} \wedge \ldots \wedge \overline{A_n}\right]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/57469c77149e052dcc138ac1d736be7c.png) is only bounded by a product of small numbers

is only bounded by a product of small numbers  and therefore likely to be very small.

and therefore likely to be very small.

Under the assumption that all of the events in  are determined by a finite collection of mutually independent random variables

are determined by a finite collection of mutually independent random variables  in

in  , Robin Moser and Gábor Tardos proposed an efficient randomized algorithm that computes an assignment to the random variables in

, Robin Moser and Gábor Tardos proposed an efficient randomized algorithm that computes an assignment to the random variables in  such that all events in

such that all events in  are avoided.

are avoided.

Hence, this algorithm can be used to efficiently construct witnesses of complex objects with prescribed features for most problems to which the Lovász Local Lemma applies.

History

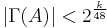

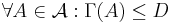

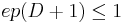

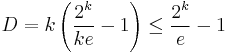

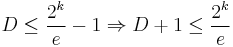

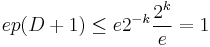

Prior to the recent work of Moser and Tardos, earlier work had also made progress in developing algorithmic versions of the Lovász Local Lemma. József Beck in 1991 first gave proof that an algorithmic version was possible.[2] In this breakthrough result, a stricter requirement was imposed upon the problem formulation than in the original non-constructive definition. Beck's approach required that for each  , the number of dependencies of A was bounded above with

, the number of dependencies of A was bounded above with  (approximately). The existential version of the Local Lemma permits a larger upper bound on dependencies:

(approximately). The existential version of the Local Lemma permits a larger upper bound on dependencies:

This bound is known to be tight. Since the initial algorithm, work has been done to push algorithmic versions of the Local Lemma closer to this tight value. Moser and Tardos's recent work are the most recent in this chain, and provide an algorithm that achieves this tight bound.

Algorithm

Let us first introduce some concepts that are used in the algorithm.

For any random variable  denotes the current assignment (evaluation) of

denotes the current assignment (evaluation) of  . An assignment (evaluation) to all random variables is denoted

. An assignment (evaluation) to all random variables is denoted  .

.

The unique minimal subset of random variables in  that determine the event

that determine the event  is denoted by

is denoted by  .

.

If the event  is true under an evaluation

is true under an evaluation  , we say that

, we say that  satisfies

satisfies  , otherwise it avoids

, otherwise it avoids  .

.

Given a set of bad events  we wish to avoid that is determined by a collection of mutually independent random variables

we wish to avoid that is determined by a collection of mutually independent random variables  , the algorithm proceeds as follows:

, the algorithm proceeds as follows:

:

:  a random evaluation of P

a random evaluation of P- while

such that A is satisfied by

such that A is satisfied by

- pick an arbitrary satisfied event

:

:  a new random evaluation of P

a new random evaluation of P

- pick an arbitrary satisfied event

- return

In the first step, the algorithm randomly initializes the current assignment  for each random variable

for each random variable  . This means that an assignment

. This means that an assignment  is sampled randomly and independently according to the distribution of the random variable

is sampled randomly and independently according to the distribution of the random variable  .

.

The algorithm then enters the main loop which is executed until all events in  are avoided and which point the algorithm returns the current assignment. At each iteration of the main loop, the algorithm picks an arbitrary satisfied event

are avoided and which point the algorithm returns the current assignment. At each iteration of the main loop, the algorithm picks an arbitrary satisfied event  (either randomly or deterministically) and resamples all the random variables that determine

(either randomly or deterministically) and resamples all the random variables that determine  .

.

Main theorem

Let  be a finite set of mutually independent random variables in the probability space

be a finite set of mutually independent random variables in the probability space  . Let

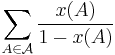

. Let  be a finite set of events determined by these variables. If there exists an assignment of reals

be a finite set of events determined by these variables. If there exists an assignment of reals  to the events such that

to the events such that

then there exists an assignment of values to the variables  avoiding all of the events in

avoiding all of the events in  .

.

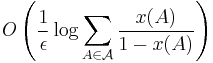

Moreover, the randomized algorithm described above resamples an event  at most an expected

at most an expected  times before it finds such an evaluation. Thus the expected total number of resampling steps and therefore the expected runtime of the algorithm is at most

times before it finds such an evaluation. Thus the expected total number of resampling steps and therefore the expected runtime of the algorithm is at most  .

.

The proof of this theorem can be found in the paper by Moser and Tardos [1]

Symmetric version

The requirement of an assignment function  satisfying a set of inequalities in the theorem above is complex and not intuitive. But this requirement can be replaced by three simple conditions:

satisfying a set of inequalities in the theorem above is complex and not intuitive. But this requirement can be replaced by three simple conditions:

, i.e. each event

, i.e. each event  depends on at most

depends on at most  other events,

other events,![\forall A \in \mathcal{A}: \Pr[A] \leq p](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/98ecd63e7503b256d58b9de3a9de487d.png) , i.e. the probability of each event

, i.e. the probability of each event  is at most

is at most  ,

, , where

, where  is the base of the natural logarithm.

is the base of the natural logarithm.

The version of the Lovász Local Lemma with these three conditions instead of the assignment function x is called the Symmetric Lovász Local Lemma. We can also state the Symmetric Algorithmic Lovász Local Lemma:

Let  be a finite set of mutually independent random variables and

be a finite set of mutually independent random variables and  be a finite set of events determined by these variables as before. If the above three conditions hold then there exists an assignment of values to the variables

be a finite set of events determined by these variables as before. If the above three conditions hold then there exists an assignment of values to the variables  avoiding all of the events in

avoiding all of the events in  .

.

Moreover, the randomized algorithm described above resamples an event  at most an expected

at most an expected  times before it finds such an evaluation. Thus the expected total number of resampling steps and therefore the expected runtime of the algorithm is at most

times before it finds such an evaluation. Thus the expected total number of resampling steps and therefore the expected runtime of the algorithm is at most  .

.

Example

The following example illustrates how the algorithmic version of the Lovász Local Lemma can be applied to a simple problem.

Let  be a CNF formula over variables

be a CNF formula over variables  , containing

, containing  clauses, and with at least

clauses, and with at least  literals in each clause, and with each variable

literals in each clause, and with each variable  appearing in at most

appearing in at most  clauses. Then,

clauses. Then,  is satisfiable.

is satisfiable.

This statement can be proven easily using the symmetric version of the Algorithmic Lovász Local Lemma. Let  be the set of mutually independent random variables

be the set of mutually independent random variables  which are sampled uniformly at random.

which are sampled uniformly at random.

Firstly, we truncate each clause in  to contain exactly

to contain exactly  literals. Since each clause is a disjunction, this does not harm satisfiability, for if we can find a satisfying assignment for the truncated formula, it can easily be extended to a satisfying assignment for the original formula by reinserting the truncated literals.

literals. Since each clause is a disjunction, this does not harm satisfiability, for if we can find a satisfying assignment for the truncated formula, it can easily be extended to a satisfying assignment for the original formula by reinserting the truncated literals.

Now, define a bad event  for each clause in

for each clause in  , where

, where  is the event that clause

is the event that clause  in

in  is unsatisfied by the current assignment. Since each clause contains

is unsatisfied by the current assignment. Since each clause contains  literals (and therefore

literals (and therefore  variables) and since all variables are sampled uniformly at random, we can bound the probability of each bad event by

variables) and since all variables are sampled uniformly at random, we can bound the probability of each bad event by ![Pr[A_j] = p = 2^{-k}](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/eab2230e4e6749c318a476bc9a7c1c8e.png) . Since each variable can appear in at most

. Since each variable can appear in at most  clauses and there are

clauses and there are  variables in each clause, each bad event

variables in each clause, each bad event  can depend on at most

can depend on at most  other events.

other events.

Finally, since  and therefore

and therefore  it follows by the symmetric Lovász Local Lemma that the probability of a random assignment to

it follows by the symmetric Lovász Local Lemma that the probability of a random assignment to  satisfying all clauses in

satisfying all clauses in  is non-zero and hence such an assignment must exist.

is non-zero and hence such an assignment must exist.

Now, the Algorithmic Lovász Local Lemma actually allows us to efficiently compute such an assignment by applying the algorithm described above. The algorithm proceeds as follows:

It starts with a random truth value assignment to the variables  sampled uniformly at random. While there exists a clause in

sampled uniformly at random. While there exists a clause in  that is unsatisfied, it randomly picks an unsatisfied clause

that is unsatisfied, it randomly picks an unsatisfied clause  in

in  and assigns a new truth value to all variables that appear in

and assigns a new truth value to all variables that appear in  chosen uniformly at random. Once all clauses in

chosen uniformly at random. Once all clauses in  are satisfied, the algorithm returns the current assignment.

are satisfied, the algorithm returns the current assignment.

This algorithm is in fact identical to WalkSAT which is used to solve general boolean satisfiability problems. Hence, the Algorithmic Lovász Local Lemma proves that WalkSAT has an expected runtime of at most  steps on CNF formulas that satisfy the two conditions above.

steps on CNF formulas that satisfy the two conditions above.

A stronger version of the above statement is proven by Moser.[3]

Applications

As mentioned before, the Algorithmic Version of the Lovász Local Lemma applies to most problems for which the general Lovász Local Lemma is used as a proof technique. Some of these problems are discussed in the following articles:

Parallel version

The algorithm described above lends itself well to parallelization, since resampling two independent events  , i.e.

, i.e.  , in parallel is equivalent to resampling

, in parallel is equivalent to resampling  sequentially. Hence, at each iteration of the main loop one can determine the maximal set of independent and satisfied events

sequentially. Hence, at each iteration of the main loop one can determine the maximal set of independent and satisfied events  and resample all events in

and resample all events in  in parallel.

in parallel.

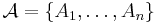

Under the assumption that the assignment function  satisfies the slightly stronger conditions:

satisfies the slightly stronger conditions:

for some  Moser and Tardos proved that the parallel algorithm achieves a better runtime complexity. In this case, the parallel version of the algorithm takes an expected

Moser and Tardos proved that the parallel algorithm achieves a better runtime complexity. In this case, the parallel version of the algorithm takes an expected

steps before it terminates. The parallel version of the algorithm can be seen as a special case of the sequential algorithm shown above, and so this result also holds for the sequential case.

References

- ^ a b Moser, Robin A.; Tardos, Gabor (2009). "A constructive proof of the general Lovász Local Lemma". arXiv:0903.0544..

- ^ Beck, József (1991), "An algorithmic approach to the Lovász Local Lemma. I", Random Structures and Algorithms 2 (4): 343–366, doi:10.1002/rsa.3240020402.

- ^ Moser, Robin A. (2008). "A constructive proof of the Lovász Local Lemma". arXiv:0810.4812..

![\forall A \in \mathcal{A}�: \Pr[A] \leq x(A) \prod_{B \in \Gamma(A)} (1-x(B))](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/b1512029ad831f3b449b5b358efb1046.png)

![\Pr\left[\,\overline{A_1} \wedge \ldots \wedge \overline{A_n}\,\right] \geq \prod_{A \in \mathcal{A}} (1-x(A)).](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/0305fa9a436977d22c81218a779f772d.png)

![\forall A \in \mathcal{A}�: Pr[A] \leq x(A) \prod_{B \in \Gamma(A)} (1-x(B))](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/ac487c2a53452368130a6d6f2cf0fd07.png)

![\forall A \in \mathcal{A}�: \Pr[A] \leq (1 - \epsilon) x(A) \prod_{B \in \Gamma(A)} (1-x(B))](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/cd1280bfa6f18342da244378b28a9453.png)