Algebraic variety

- This article is about algebraic varieties. For the term "a variety of algebras", and an explanation of the difference between a variety of algebras and an algebraic variety, see variety (universal algebra).

In mathematics, an algebraic variety is the set of solutions of a system of polynomial equations. Algebraic varieties are one of the central objects of study in algebraic geometry. The word "variety" is employed in the sense of a manifold, for which cognates of the word "variety" are used in the Romance languages.

Proven around the year 1800, the fundamental theorem of algebra establishes a link between algebra and geometry by showing that a monic polynomial in one variable with complex coefficients (an algebraic object) is determined by the set of its roots (a geometric object). Building on this result, Hilbert's Nullstellensatz provides a fundamental correspondence between ideals of polynomial rings and subsets of affine space. Using the Nullstellensatz and related results, mathematicians are able to capture the geometric notion of a variety in algebraic terms as well as bring geometry to bear on questions of ring theory.

Contents |

Formal definitions

Algebraic varieties can be classed into four kinds: affine varieties, quasi-affine varieties, projective varieties, and quasi-projective varieties. There is also the more general notion of an abstract algebraic variety.

Affine varieties

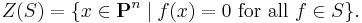

Let k be an algebraically closed field and let An be an affine n-space over k. The polynomials ƒ in the ring k[x1, ..., xn] can be viewed as k-valued functions on An by evaluating ƒ at the points in An. For each set S of polynomials in k[x1, ..., xn], define the zero-locus Z(S) to be the set of points in An on which the functions in S simultaneously vanish, that is to say

A subset V of An is called an affine algebraic set if V = Z(S) for some S. A nonempty affine algebraic set V is called irreducible if it cannot be written as the union of two proper algebraic subsets. An irreducible affine algebraic set is also called an affine variety. (Many authors use the phrase affine variety to refer to any affine algebraic set, irreducible or not; this article will use the stricter definition.)

Affine varieties can be given a natural topology by declaring the closed sets to be precisely the affine algebraic sets. This topology is called the Zariski topology.

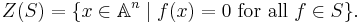

Given a subset V of An, we define I(V) to be the ideal of all functions vanishing on V:

For any affine algebraic set V, the coordinate ring or structure ring of V is the quotient of the polynomial ring by this ideal.

Projective varieties

Let k be an algebraically closed field and let Pn be a projective n-space over k. Let f ∈ k [x0, ..., xn] be a homogeneous polynomial of degree d. It is not well-defined to evaluate f on points in Pn in homogeneous coordinates. However, because f is homogeneous, f(λx0, ..., λxn) = λdf(x0, ..., xn), so it does make sense to ask whether f vanishes at a point [x0 : ... : xn]. For each set S of homogeneous polynomials, define the zero-locus of S to be the set of points in Pn on which the functions in S vanish:

A subset V of Pn is called a projective algebraic set if V = Z(S) for some S. An irreducible projective algebraic set is called a projective variety.

Projective varieties are also equipped with the Zariski topology by declaring all algebraic sets to be closed.

Given a subset V of Pn, let I(V) be the ideal generated by all homogeneous polynomials vanishing on V. For any projective algebraic set V, the coordinate ring of V is the quotient of the polynomial ring by this ideal.

Examples

Affine algebraic variety

Example 1

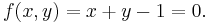

Let k be the field of complex numbers C. Let A2 be a two dimensional affine space over C. The polynomials f in the ring k[x, y] can be viewed as complex valued functions on A2 by evaluating ƒ at the points in A2. Let subset S of k[x, y] contain a single element f(x, y):

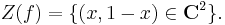

The zero-locus of f(x, y) is the set of points in A2 on which this function vanishes: it is the set of all pairs of complex numbers (x,y) such that y = 1 − x, commonly known as a line. This is the set Z(f):

Thus the subset V = Z(f) of A2 is an algebraic set. The set V is not an empty set. And it is irreducible as it cannot be written as the union of two proper algebraic subsets. Thus it is an affine algebraic variety.

Example 2

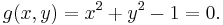

Let again k be the field of complex numbers C. Let A2 be a two dimensional affine space over C. The polynomials g in the ring k[x, y] can be viewed as complex valued functions on A2 by evaluating g at the points in A2. Let subset S of k[x, y] contain a single element g(x, y):

The zero-locus of g(x, y) is the set of points in A2 on which this function vanishes, that is the set of points (x,y) such that xx + yy = 1, commonly known as a circle.

Basic results

- An affine algebraic set V is a variety if and only if I(V) is a prime ideal; equivalently, V is a variety if and only if its coordinate ring is an integral domain.

- Every nonempty affine algebraic set may be written uniquely as a union of algebraic varieties (where none of the sets in the decomposition are subsets of each other).

- Let k[V] be the coordinate ring of the variety V. Then the dimension of V is the transcendence degree of the field of fractions of k[V] over k.

Isomorphism of algebraic varieties

Let V1 and V2 be algebraic varieties. We say that V1 and V2 are isomorphic, and write V1 ≅ V2, if there are regular maps φ : V1 → V2 and ψ : V2 → V1 such that the compositions ψ ° φ and φ ° ψ are the identity maps on V1 and V2 respectively.

Discussion and generalizations

The basic definitions and facts above enable one to do classical algebraic geometry. To be able to do more — for example, to deal with varieties over fields that are not algebraically closed — some foundational changes are required. The modern notion of a variety is considerably more abstract than the one above, though equivalent in the case of varieties over algebraically closed fields. An abstract algebraic variety is a particular kind of scheme; the generalization to schemes on the geometric side enables an extension of the correspondence described above to a wider class of rings. A scheme is a locally ringed space such that every point has a neighbourhood, which, as a locally ringed space, is isomorphic to a spectrum of a ring. Basically, a variety is a scheme whose structure sheaf is a sheaf of k-algebras with the property that the rings R that occur above are all domains and are all finitely generated k-algebras, i.e., quotients of polynomial algebras by prime ideals.

This definition works over any field k. It allows you to glue affine varieties (along common open sets) without worrying whether the resulting object can be put into some projective space. This also leads to difficulties since one can introduce somewhat pathological objects, e.g. an affine line with zero doubled. Such objects are usually not considered varieties, and are eliminated by requiring the schemes underlying a variety to be separated. (Strictly speaking, there is also a third condition, namely, that one needs only finitely many affine patches in the definition above.)

Some modern researchers also remove the restriction on a variety having integral domain affine charts, and when speaking of a variety simply mean that the affine charts have trivial nilradical.

A complete variety is a variety such that any map from an open subset of a nonsingular curve into it can be extended uniquely to the whole curve. Every projective variety is complete, but not vice versa.

These varieties have been called 'varieties in the sense of Serre', since Serre's foundational paper FAC on sheaf cohomology was written for them. They remain typical objects to start studying in algebraic geometry, even if more general objects are also used in an auxiliary way.

One way that leads to generalisations is to allow reducible algebraic sets (and fields k that aren't algebraically closed), so the rings R may not be integral domains. A more significant modification is to allow nilpotents in the sheaf of rings. A nilpotent in a field must be 0: these if allowed in coordinate rings aren't seen as coordinate functions.

From the categorical point of view, nilpotents must be allowed, in order to have finite limits of varieties (to get fiber products). Geometrically this says that fibres of good mappings may have 'infinitesimal' structure. In the theory of schemes of Grothendieck these points are all reconciled: but the general scheme is far from having the immediate geometric content of a variety.

There are further generalizations called algebraic spaces and stacks.

Algebraic manifolds

An algebraic manifold is an algebraic variety which is also an m-dimensional manifold, and hence every sufficiently small local patch is isomorphic to km. Equivalently, the variety is smooth (free from singular points). When k is the real numbers, R, algebraic manifolds are called Nash manifolds. Algebraic manifolds can be defined as the zero set of a finite collection of analytic algebraic functions. Projective algebraic manifolds are an equivalent definition for projective varieties. The Riemann sphere is one example.

See also

- function field of an algebraic variety

- dimension of an algebraic variety

- singular point of an algebraic variety

- birational geometry

- abelian variety

- motive

- scheme

- analytic variety

References

- David Cox; John Little, Don O'Shea (1997). Ideals, Varieties, and Algorithms (second ed.). Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-94680-2.

- David Dummit; Richard Foote (2003). Abstract Algebra (third ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-43334-9.

- David Eisenbud (1999). Commutative Algebra with a View Toward Algebraic Geometry. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-94269-6.

- Robin Hartshorne (1977). Algebraic Geometry. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-90244-9.

- Milne, James S. (2008). "Algebraic Geometry". http://www.jmilne.org/math/CourseNotes/ag.html. Retrieved 2009-09-01.

This article incorporates material from Isomorphism of varieties on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share-Alike License.

![I(V) = \{f \in k[x_1,\cdots,x_n] \mid f(x) = 0 \mbox{ for all } x\in V\}.](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/aa36effba81feb8a96813b2e6eaebd21.png)