Omar Khayyám

A depiction of Omar Khayyám, in the works of Edward FitzGerald |

|

| Full name | Omar Khayyám عمر خیام |

|---|---|

| Born | 18 May[1] 1048[2] |

| Died | 1131 (aged 82/83)[2] |

| School | Persian mathematics, Persian poetry, Persian philosophy |

| Main interests | Mathematics, Philosophy, Astronomy, Poetry, |

|

Influenced by

|

|

|

Influenced

|

|

Omar Khayyám (1048–1131; Persian: عمر خیام) was a Persian polymath: philosopher, mathematician, astronomer and poet. He also wrote treatises on mechanics, geography, mineralogy, music, climatology and theology.[3]

Born in Nishapur, at a young age he moved to Samarkand and obtained his education there, afterwards he moved to Bukhara and became established as one of the major mathematicians and astronomers of the medieval period. He is the author of one of the most important treatises on algebra written before modern times, the Treatise on Demonstration of Problems of Algebra, which includes a geometric method for solving cubic equations by intersecting a hyperbola with a circle.[4] He contributed to a calendar reform.

His significance as a philosopher and teacher, and his few remaining philosophical works, have not received the same attention as his scientific and poetic writings. Zamakhshari referred to him as “the philosopher of the world”. Many sources have testified that he taught for decades the philosophy of Ibn Sina in Nishapur where Khayyám was born and buried and where his mausoleum today remains a masterpiece of Iranian architecture visited by many people every year.[5]

Outside Iran and Persian speaking countries, Khayyám has had an impact on literature and societies through the translation of his works and popularization by other scholars. The greatest such impact was in English-speaking countries; the English scholar Thomas Hyde (1636–1703) was the first non-Persian to study him. The most influential of all was Edward FitzGerald (1809–83),[6] who made Khayyám the most famous poet of the East in the West through his celebrated translation and adaptations of Khayyám's rather small number of quatrains (rubaiyaas) in Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám.

Contents |

Early life

Khayyám's full name was Ghiyath al-Din Abu'l-Fath 'Umar ibn Ibrahim Al-Nishapuri al-Khayyami (Persian: غیاث الدین ابو الفتح عمر بن ابراهیم خیام نیشاپوری). He was born in Nishapur,(modern-day Iran), then a Seljuq capital in Khorasan,[7][8][9] which rivaled Cairo or Baghdad in cultural prominence in that era. He is thought to have been born into a family of tent makers (khayyami, lit. in Farsi "tent-maker"), which he would make this into a play on words later in life:

Khayyám, who stitched the tents of science,

Has fallen in grief's furnace and been suddenly burned,

The shears of Fate have cut the tent ropes of his life,

And the broker of Hope has sold him for nothing!— Omar Khayyám[4]

He spent part of his childhood in the town of Balkh (present northern Afghanistan), studying under the well-known scholar Sheikh Muhammad Mansuri. He later studied under Imam Mowaffaq Nishapuri, who was considered one of the greatest teachers of the Khorasan region. Throughout his life Omar Khayyám was dedicated to his efforts and abilities, in the day he would teach Algebra and Geometry in the evening he would attend the Seljuq court as an adviser of Malik-Shah I[10] and at night he would study Astronomy and complete the important aspects of the Jalali calendar.

Omar Khayyám's years in Isfahan were very productive ones but after the death of the Seljuq Sultan Malik-Shah I (presumably by the Assassins sect), the Sultan's widow turned against him as an adviser and and soon therefore Omar Khayyám set out on his Hajj or Pilgrimage to Mecca and Medina. He was then allowed to work as a court astrologer and was permitted to return to Nishapur where he was famous for works and continued to teach mathematics, astronomy and even medicine.[11]

Mathematician

Khayyám was famous during his times as a mathematician. He wrote the influential Treatise on Demonstration of Problems of Algebra (1070), which laid down the principles of algebra, part of the body of Persian Mathematics that was eventually transmitted to Europe. In particular, he derived general methods for solving cubic equations and even some higher orders.

In the Treatise he wrote on the triangular array of binomial coefficients known as Pascal's triangle. In 1077, Khayyám wrote Sharh ma ashkala min musadarat kitab Uqlidis (Explanations of the Difficulties in the Postulates of Euclid) published in English as "On the Difficulties of Euclid's Definitions".[12] An important part of the book is concerned with Euclid's famous parallel postulate, which attracted the interest of Thabit ibn Qurra. Al-Haytham had previously attempted a demonstration of the postulate; Khayyám's attempt was a distinct advance, and his criticisms made their way to Europe, and may have contributed to the eventual development of non-Euclidean geometry.

Omar Khayyám had notable works in geometry, specifically on the theory of proportions, his notable contemporary mathematicians included Al-Khazini and Abu Hatim al-Muzaffar ibn Ismail al-Isfizari[13]

Theory of parallels

Khayyám wrote a book entitled Explanations of the difficulties in the postulates in Euclid's Elements. The book consists of several sections on the parallel postulate (Book I), on the Euclidean definition of ratios and the Anthyphairetic ratio (modern continued fractions) (Book II), and on the multiplication of ratios (Book III).

The first section is a treatise containing some propositions and lemmas concerning the parallel postulate. It has reached the Western world from a reproduction in a manuscript written in 1387-88 AD by the Persian mathematician Tusi. Tusi mentions explicitly that he re-writes the treatise "in Khayyám's own words" and quotes Khayyám, saying that "they are worth adding to Euclid's Elements (first book) after Proposition 28."[14] This proposition[15] states a condition enough for having two lines in plane parallel to one another. After this proposition follows another, numbered 29, which is converse to the previous one.[16] The proof of Euclid uses the so-called parallel postulate (numbered 5). Objection to the use of parallel postulate and alternative view of proposition 29 have been a major problem in foundation of what is now called non-Euclidean geometry.

The treatise of Khayyám can be considered as the first treatment of parallels axiom which is not based on petitio principii but on more intuitive postulate. Khayyám refutes the previous attempts by other Greek and Persian mathematicians to prove the proposition. And he, as Aristotle, refuses the use of motion in geometry and therefore dismisses the different attempt by Ibn Haytham too.[17] In a sense he made the first attempt at formulating a non-Euclidean postulate as an alternative to the parallel postulate,[18]

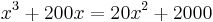

Geometric algebra

This philosophical view of mathematics (see below) has had a significant impact on Khayyám's celebrated approach and method in geometric algebra and in particular in solving cubic equations. In that his solution is not a direct path to a numerical solution and in fact his solutions are not numbers but rather line segments. In this regard Khayyám's work can be considered the first systematic study and the first exact method of solving cubic equations.[20]

In an untitled writing on cubic equations by Khayyám discovered in 20th century,[19] where the above quote appears, Khayyám works on problems of geometric algebra. First is the problem of "finding a point on a quadrant of a circle such that when a normal is dropped from the point to one of the bounding radii, the ratio of the normal's length to that of the radius equals the ratio of the segments determined by the foot of the normal." Again in solving this problem, he reduces it to another geometric problem: "find a right triangle having the property that the hypotenuse equals the sum of one leg (i.e. side) plus the altitude on the hypotenuse.[21] To solve this geometric problem, he specializes a parameter and reaches the cubic equation  .[19] Indeed, he finds a positive root for this equation by intersecting a hyperbola with a circle.

.[19] Indeed, he finds a positive root for this equation by intersecting a hyperbola with a circle.

This particular geometric solution of cubic equations has been further investigated and extended to degree four equations.[22]

Regarding more general equations he states that the solution of cubic equations requires the use of conic sections and that it cannot be solved by ruler and compass methods.[19] A proof of this impossibility was plausible only 750 years after Khayyám died. In this paper Khayyám mentions his will to prepare a paper giving full solution to cubic equations: "If the opportunity arises and I can succeed, I shall give all these fourteen forms with all their branches and cases, and how to distinguish whatever is possible or impossible so that a paper, containing elements which are greatly useful in this art will be prepared."[19]

This refers to the book Treatise on Demonstrations of Problems of Algebra (1070), which laid down the principles of algebra, part of the body of Persian Mathematics that was eventually transmitted to Europe.[20] In particular, he derived general methods for solving cubic equations and even some higher orders.

Binomial theorem and extraction of roots

From the Indians one has methods for obtaining square and cube roots, methods which are based on knowledge of individual cases, namely the knowledge of the squares of the nine digits 12, 22, 32 (etc.) and their respective products, i.e. 2 × 3 etc. We have written a treatise on the proof of the validity of those methods and that they satisfy the conditions. In addition we have increased their types, namely in the form of the determination of the fourth, fifth, sixth roots up to any desired degree. No one preceded us in this and those proofs are purely arithmetic, founded on the arithmetic of The Elements.

This particular remark of Khayyám and certain propositions found in his Algebra book has made some historians of mathematics believe that Khayyám had indeed a binomial theorem up to any power. The case of power 2 is explicitly stated in Euclid's elements and the case of at most power 3 had been established by Indian mathematicians. Khayyám was the mathematician who noticed the importance of a general binomial theorem. The argument supporting the claim that Khayyám had a general binomial theorem is based on his ability to extract roots.[24]

Khayyám-Saccheri quadrilateral

The Saccheri quadrilateral was first considered by Khayyám in the late 11th century in Book I of Explanations of the Difficulties in the Postulates of Euclid.[25] Unlike many commentators on Euclid before and after him (including of course Saccheri), Khayyám was not trying to prove the parallel postulate as such but to derive it from an equivalent postulate he formulated from "the principles of the Philosopher" (Aristotle):

- Two convergent straight lines intersect and it is impossible for two convergent straight lines to diverge in the direction in which they converge.[26]

Khayyám then considered the three cases (right, obtuse, and acute) that the summit angles of a Saccheri quadrilateral can take and after proving a number of theorems about them, he (correctly) refuted the obtuse and acute cases based on his postulate and hence derived the classic postulate of Euclid.

It wasn't until 600 years later that Giordano Vitale made an advance on Khayyám in his book Euclide restituo (1680, 1686), when he used the quadrilateral to prove that if three points are equidistant on the base AB and the summit CD, then AB and CD are everywhere equidistant. Saccheri himself based the whole of his long, heroic, and ultimately flawed proof of the parallel postulate around the quadrilateral and its three cases, proving many theorems about its properties along the way.

Astronomer

Like most Persian mathematicians of the period, Khayyám was famous as an astronomer. In 1073, the Seljuk Sultan Sultan Jalal al-Din Malekshah Saljuqi (Malik-Shah I, 1072–92), invited Khayyám to build an observatory, along with various other distinguished scientists. According to some accounts, the version of the medieval Iranian calendar in which 2,820 solar years together contain 1,029,983 days (or 683 leap years, for an average year length of 365.24219858156 days) was based on the measurements of Khayyám and his colleagues.[31] Another proposal is that Khayyám's calendar simply contained eight leap years every thirty-three years (for a year length of 365.2424 days).[32] In either case, his calendar was more accurate to the mean tropical year than the Gregorian calendar of 500 years later. The modern Iranian calendar is based on his calculations.

Calendar reform

Khayyám is claimed to be a member of a panel that introduced several reforms to the Persian calendar. On March 15, 1079, Sultan Malik Shah I accepted this corrected calendar as the official Persian calendar.[33]

This calendar was known as Jalali calendar after the Sultan, and was in force across Greater Iran from the 11th to the 20th centuries. It is the basis of the Iranian calendar which is followed today in Iran and Afghanistan. While the Jalali calendar is more accurate than the Gregorian, it is based on actual solar transit, (similar to Hindu calendars), and requires an Ephemeris for calculating dates. The lengths of the months can vary between 29 and 31 days depending on the moment when the sun crossed into a new zodiacal area (an attribute common to most Hindu calendars). This meant that seasonal errors were lower than in the Gregorian calendar.

The modern-day Iranian calendar standardizes the month lengths based on a reform from 1925, thus minimizing the effect of solar transits. Seasonal errors are somewhat higher than in the Jalali version, but leap years are calculated as before.

Poet

He is believed to have written about a thousand four-line verses or rubaiyat (quatrains). In the English-speaking world, he was introduced through the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám which are rather free-wheeling English translations by Edward FitzGerald (1809–1883). Other English translations of parts of the rubáiyát (rubáiyát meaning "quatrains") exist, but FitzGerald's are the most well known.

Ironically, FitzGerald's translations reintroduced Khayyám to Iranians "who had long ignored the Neishapouri poet." A 1934 book by one of Iran's most prominent writers, Sadeq Hedayat, Songs of Khayyam, (Taranehha-ye Khayyam) is said to have "shaped the way a generation of Iranians viewed" the poet.[34]

Khayyam's poetry is translated to many languages.

Khayyám's personal beliefs are not known with certainty, but much is discernible from his poetic oeuvre.

Poetry

Omar Khayyám's poems have been translated many times in many languages and many translators have claimed that their translations of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám literal, poetic and less controversial than that of Edward Fitzgerald.[35]

The Moving Finger writes; and, having writ,

Moves on: nor all thy Piety nor Wit,

Shall lure it back to cancel half a Line,

Nor all thy Tears wash out a Word of it.

But helpless pieces in the game He plays,

Upon this chequer-board of Nights and Days,

He hither and thither moves, and checks ... and slays,

Then one by one, back in the Closet lays.

And, as the Cock crew, those who stood before

The Tavern shouted - "Open then the Door!

You know how little time we have to stay,

And once departed, may return no more."

A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread--and Thou,

Beside me singing in the Wilderness,

And oh, Wilderness is Paradise enow.

If chance supplied a loaf of white bread,

Two casks of wine and a leg of mutton,

In the corner of a garden with a tulip-cheeked girl,

There'd be enjoyment no Sultan could outdo.

Myself when young did eagerly frequent

Doctor and Saint, and heard great Argument

About it and about: but evermore

Came out of the same Door as in I went.

With them the Seed of Wisdom did I sow,

And with my own hand labour'd it to grow:

And this was all the Harvest that I reap'd -

"I came like Water, and like Wind I go."

Into this Universe, and why not knowing,

Nor whence, like Water willy-nilly flowing:

And out of it, as Wind along the Waste,

I know not whither, willy-nilly blowing.

And that inverted Bowl we call The Sky,

Whereunder crawling coop't we live and die,

Lift not thy hands to It for help - for It

Rolls impotently on as Thou or I.

.........................................

Views on religion

How much more of the mosque, of prayer and fasting?

Better go drunk and begging round the taverns.

Khayyam, drink wine, for soon this clay of yours

Will make a cup, bowl, one day a jar.

When once you hear the roses are in bloom,

Then is the time, my love, to pour the wine;

Houris and palaces and Heaven and Hell-

These are but fairy-tales, forget them all.

There have been widely divergent views on Khayyám. According to Seyyed Hossein Nasr no other Iranian writer/scholar is viewed in such extremely differing ways. At one end of the spectrum there are nightclubs named after Khayyám, and he is seen as an agnostic hedonist. On the other end of the spectrum, he is seen as a mystical Sufi poet influenced by platonic traditions.

The verse: "Enjoy wine and women and don't be afraid, Allah has compassion," suggests that he was not an atheist. He further believes that it is almost certain that Khayyám objected to the notion that every particular event and phenomenon was the result of divine intervention. Nor did he zealously believe in an afterlife with a Judgment Day or rewards and punishments.[36] Instead, he supported the view that laws of nature explained all phenomena of observed life. One contemporary writes: "I did not observe that he had any great belief in astrological predictions or speculations; nor have I seen or heard of any of the great (scientists) who had such belief."

The following two quatrains are representative of numerous others that serve to reject many tenets of religious dogma:

- خيام اگر ز باده مستى خوش باش

- با ماه رخى اگر نشستى خوش باش

- چون عاقبت كار جهان نيستى است

- انگار كه نيستى، چو هستى خوش باش

which translates in FitzGerald's work as:

- And if the Wine you drink, the Lip you press,

- End in the Nothing all Things end in — Yes —

- Then fancy while Thou art, Thou art but what

- Thou shalt be — Nothing — Thou shalt not be less.

A more literal translation could read:

- If with wine you are drunk be happy,

- If seated with a moon-faced (beautiful), be happy,

- Since the end purpose of the universe is nothing-ness;

- Hence picture your nothing-ness, then while you are, be happy!

- آنانكه ز پيش رفتهاند اى ساقى

- درخاك غرور خفتهاند اى ساقى

- رو باده خور و حقيقت از من بشنو

- باد است هرآنچه گفتهاند اى ساقى

which FitzGerald has erroneously and mistakenly interpreted as:

- Why, all the Saints and Sages who discuss’d

- Of the Two Worlds so learnedly — are thrust

- Like foolish Prophets forth; their Words to Scorn

- Are scatter’d, and their Mouths are stopt with Dust.

A literal translation, in an ironic echo of "all is vanity", could read:

- Those who have gone forth, thou cup-bearer,

- Have fallen upon the dust of pride, thou cup-bearer,

- Drink wine and hear from me the truth:

- (Hot) air is all that they have said, thou cup-bearer.

But some specialists, like Seyyed Hossein Nasr who looks at the available philosophical works of Khayyám, maintain that it is really reductive to just look at the poems (which are sometimes doubtful) to establish his personal views about God or religion; in fact, he even wrote a treatise entitled "al-Khutbat al-gharrå˘" (The Splendid Sermon) on the praise of God, where he holds orthodox views, agreeing with Avicenna on Divine Unity.[5] In fact, this treatise is not an exception, and S.H. Nasr gives an example where he identified himself as a Sufi, after criticizing different methods of knowing God, preferring the intuition over the rational (opting for the so-called "kashf", or unveiling, method):[5]

"... Fourth, the Sufis, who do not seek knowledge by ratiocination or discursive thinking, but by purgation of their inner being and the purifying of their dispositions. They cleanse the rational soul of the impurities of nature and bodily form, until it becomes pure substance. When it then comes face to face with the spiritual world, the forms of that world become truly reflected in it, without any doubt or ambiguity.This is the best of all ways, because it is known to the servant of God that there is no reflection better than the Divine Presence and in that state there are no obstacles or veils in between. Whatever man lacks is due to the impurity of his nature. If the veil be lifted and the screen and

obstacle removed, the truth of things as they are will become manifest and known. And the Master of creatures [the Prophet Muhammad]—upon whom be peace—indicated this when he said: “Truly, during the days of your existence, inspirations come from God. Do you not want to follow them?” Tell unto reasoners that, for the lovers of God, intuition is guide, not discursive thought."—Omar Khayyám[37]

The same author goes on by giving other philosophical writings which are totally compatible with the religion of Islam, as the "al-Risålah fil-wujud" (Treatise on Being), written in Arabic, which begin with Quranic verses and asserting that all things come from God, and there is an order in these things. In another work, "Risålah jawåban li-thalåth maså˘il" (Treatise of Response to Three Questions), he gives a response to question on, for instance, the becoming of the soul post-mortem. S.H. Nasr even gives some poetry where he is perfectly in favor of Islamic orthodoxy, but expressing mystical views (God's goodness, the ephemerical state of this life, ...):[5]

- Thou hast said that Thou wilt torment me,

- But I shall fear not such a warning.

- For where Thou art, there can be no torment,

- And where Thou art not, how can such a place exist?

- The rotating wheel of heaven within which we wonder,

- Is an imaginal lamp of which we have knowledge by similitude.

- The sun is the candle and the world the lamp,

- We are like forms revolving within it.

- A drop of water falls in an ocean wide,

- A grain of dust becomes with earth allied;

- What doth thy coming, going here denote?

- A fly appeared a while, then invisible he became.

Considering misunderstandings about Khayyám in the West and elsewhere, S.H. Nasr concludes by saying that if a correct study of the authentic rubaiyat is done, but along with the philosophical works, or even the spiritual biography entitled Sayr wa sulak (Spiritual Wayfaring), we can no longer view the man as a simple hedonistic wine-lover, or even an early skeptic, but a profound mystical thinker and scientist whose works are more important than some verses.[5] C.H.A. Bjerregaard earlier summarised the situation:

"The writings of Omar Khayyam are good specimens of Sufism but are not valued in the West as they ought to be, and the mass of the people know him only through the poems of Edward Fitzgerald which is unfortunate. It is unfortunate because Fitzgerald is not faithful to his master and model, and at times he lays words upon the tongue of the Sufi which are blasphemous. Such outrageous language is that of the eighty-first quatrain for instance. Fitzgerald is doubly guilty because he was more of a Sufi than he was willing to admit."[38]

Abdullah Dougan, a modern Naqshbandi Sufi, provides commentary[39] on the role and contribution of Omar Khayyam to Sufi thought. Dougan says that while Omar is a minor Sufi teacher compared to the giants – Rumi, Attar and Sana’i – one aspect that makes Omar’s work so relevant and accessible is its very human scale as we can feel for him and understand his approach. The argument over the quality of Fitzgerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat has, according to Dougan, diverted attention from a fuller understanding of the deeply esoteric message contained in Omar’s actual material – "Every line of the Rubaiyat has more meaning than almost anything you could read in Sufi literature".

Philosopher

Khayyám himself rejects to be associated with the title falsafi- (lit. philosopher) in the sense of Aristotelian one and stressed he wishes "to know who I am". In the context of philosophers he was labeled by some of his contemporaries as "detached from divine blessings".[40]

It is now established that Khayyám taught for decades the philosophy of Avicena, especially "the Book of Healing", in his home town Nishapur, till his death.[5] In an incident he had been requested to comment on a disagreement between Avicena and a philosopher called Abu'l-Barakat (known also as Nathanel) who had criticized Avicena strongly. Khayyám is said to have answered "[he] does not even understand the sense of the words of Avicenna, how can he oppose what he does not know?"[40]

Khayyám the philosopher could be understood from two rather distinct sources. One is through his Rubaiyat and the other through his own works in light of the intellectual and social conditions of his time.[41] The latter could be informed by the evaluations of Khayyám's works by scholars and philosophers such as Bayhaqi, Nezami Aruzi, and Zamakhshari and Sufi poets and writers Attar Nishapuri and Najmeddin Razi.

As a mathematician, Khayyám has made fundamental contributions to the Philosophy of mathematics especially in the context of Persian Mathematics and Persian philosophy with which most of the other Persian scientists and philosophers such as Avicenna, Biruni, and Tusi are associated. There are at least three basic mathematical ideas of strong philosophical dimensions that can be associated with Khayyám.

- Mathematical order: From where does this order issue, and why does it correspond to the world of nature? His answer is in one of his philosophical "treatises on being". Khayyám's answer is that "the Divine Origin of all existence not only emanates wojud or being, by virtue of which all things gain reality, but It is the source of order that is inseparable from the very act of existence."[41]

- The significance of postulates (i.e. axiom) in geometry and the necessity for the mathematician to rely upon philosophy and hence the importance of the relation of any particular science to prime philosophy. This is the philosophical background to Khayyám's total rejection of any attempt to "prove" the parallel postulate, and in turn his refusal to bring motion into the attempt to prove this postulate, as had Ibn al-Haytham, because Khayyám associated motion with the world of matter, and wanted to keep it away from the purely intelligible and immaterial world of geometry.[41]

- Clear distinction made by Khayyám, on the basis of the work of earlier Persian philosophers such as Avicenna, between natural bodies and mathematical bodies. The first is defined as a body that is in the category of substance and that stands by itself, and hence a subject of natural sciences, while the second, called "volume", is of the category of accidents (attributes) that do not subsist by themselves in the external world and hence is the concern of mathematics. Khayyám was very careful to respect the boundaries of each discipline, and criticized Ibn al-Haytham in his proof of the parallel postulate precisely because he had broken this rule and had brought a subject belonging to natural philosophy, that is, motion, which belongs to natural bodies, into the domain of geometry, which deals with mathematical bodies.[41]

Legacy

- A lunar crater Omar Khayyam was named after him in 1970.

- A minor planet called 3095 Omarkhayyam, discovered by Soviet astronomer Lyudmila Zhuravlyova in 1980, is named after him.[42]

See also

- Astronomy in medieval Islam

- Mathematics in medieval Islam

- Nozhat al-Majales

- Omar Khayyam (film)

- The Keeper: The Legend of Omar Khayyam

Notes

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Online

- ^ a b Professor Seyyed Hossein Nasr and Professor Mehdi Aminrazavi. “An Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, Vol. 1: From Zoroaster to ‘Umar Khayyam”, I.B. Tauris in association with The Institute of Ismaili Studies, 2007.

- ^ Omar Khayyam and Max Stirner

- ^ a b He also founded the Islamic calender. "Omar Khayyam". The MacTutor History of Mathematics archive. http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Mathematicians/Khayyam.html.

- ^ a b c d e f S. H. Nasr Chapter 9.

- ^ Jos Biegstraaten

- ^ The Tomb of Omar Khayyâm, George Sarton, Isis, Vol. 29, No. 1 (Jul., 1938), 15.

- ^ Edward FitzGerald, Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, Ed. Christopher Decker, (University of Virginia Press, 1997), xv;"The Saljuq Turks had invaded the province of Khorasan in the 1030s, and the city of Nishapur surrendered to them voluntarily in 1038. Thus Omar Khayyam grew to maturity during the first of the several alien dynasties that would rule Iran until the twentieth century.".

- ^ Peter Avery and John Heath-Stubbs, The Ruba'iyat of Omar Khayyam, (Penguin Group, 1981), 14;"These dates, 1048-1131, tell us that Khayyam lived when the Saljuq Turkish Sultans were extending and consolidating their power over Persia and when the effects of this power were particularly felt in Nishapur, Khayyam's birthplace.".

- ^ Edward FitzGerald, Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, xv.

- ^ http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/428267/Omar-Khayyam

- ^ The Quatrains of Omar Khayyam E.H. Whinfield Pg 14

- ^ http://www.muslimheritage.com/fstc/newsletter/issue8.htm

- ^ (Smith 1935, p. 6)

- ^ Euclid. "Proposition 28". Elements. I. 28. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0086;query=proposition%3D%2328;layout=;loc=1.29. "If a straight line falling on two straight lines make the exterior angle equal to the interior and opposite angle on the same side, or the interior angles on the same side equal to two right angles, the straight lines will be parallel to one another."

- ^ Euclid. "Proposition 29". Elements. I. 29. http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/cgi-bin/ptext?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0086;query=proposition%3D%2328;layout=;loc=1.29. "A straight line falling on parallel straight lines makes the alternate angles equal to one another, the exterior angle equal to the interior and opposite angle, and the interior angles on the same side equal to two right angles."

- ^ (Rozenfeld 1988, pp. 64–65)

- ^ (Katz 1998, p. 270). Excerpt: In some sense, his treatment was better than ibn al-Haytham's because he explicitly formulated a new postulate to replace Euclid's rather than have the latter hidden in a new definition.

- ^ a b c d e A. R. Amir-Moez, "A Paper of Omar Khayyám", Scripta Mathematica 26 (1963), pp. 323-37

- ^ a b Mathematical Masterpieces: Further Chronicles by the Explorers, p. 92

- ^ E. S. Kennedy, Chapter 10 in Cambridge History of Iran (5), p. 665.

- ^ A. R. Amir-Moez, Khayyam's Solution of Cubic Equations, Mathematics Magazine, Vol. 35, No. 5 (Nov., 1962), pp. 269-271. This paper contains an extension by the late M. Hashtroodi of Khayyám's method to degree four equations.

- ^ "Muslim extraction of roots". Mactutor History of Mathematics. http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Extras/Muslim_roots.html.

- ^ J. L. Coolidge, The Story of the Binomial Theorem, Amer. Math. Monthly, Vol. 56, No. 3 (Mar., 1949), pp. 147-157

- ^ Boris Abramovich Rozenfelʹd (1988), A History of Non-Euclidean Geometry: Evolution of the Concept of a Geometric Space, p. 65. Springer, ISBN 0-387-96458-4.

- ^ Boris A Rosenfeld and Adolf P Youschkevitch (1996), Geometry, p.467 in Roshdi Rashed, Régis Morelon (1996), Encyclopedia of the history of Arabic science, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-12411-5.

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/persian/arts/story/2008/03/080312_shr-hh-calendar4.shtml

- ^ http://www.bbc.co.uk/persian/arts/story/2006/04/060421_pm-cy-calendar-malekpour.shtml

- ^ http://www.ghiasabadi.com/pasdashtegahshomari.html

- ^ http://www.ghiasabadi.com/jalali.html

- ^ Early History of Astronomy - The Middle East

- ^ Mapping Time: The Calendar and its History by E.G. Richards (Oxford University Press, 1998) ISBN 0-19-282065-7, p. 235

- ^ "Omar Khayyám". The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition.. 2001-05. http://www.bartleby.com/65/om/OmarKhay.html. Retrieved 2007-06-10.Here Omar Khayyám is described as "poet and mathematician", i.e. poet appearing first.

- ^ Molavi, Afshin, The Soul of Iran, Norton, (2005), p.110

- ^ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ajjada_Adibhatla_Narayana_Dasu

- ^ Sadegh Hedayat, the greatest Persian novelist and short-story writer of the twentieth century pointed out that Khayyám from "his youth to his death remained a materialist, pessimist, agnostic". "Khayyam looked at all religions questions with a skeptical eye", continues Hedayat, "and hated the fanaticism, narrow-mindedness, and the spirit of vengeance of the mullas, the so-called religious scholars".

- ^ Also Nasr, Science and Civilization in Islam, pp. 33–34. See also pp. 52–53 of the same work; also F. Schuon, Spiritual Perspectives and Human Facts, pp. 76–77.

- ^ C. H. A. Bjerregaard (1915). Sufism: Omar Khayyam and E. Fitzgerald. The Sufi Publishing Society. Preface.

- ^ Abdullah Dougan Who is the Potter? Gnostic Press 1991 ISBN 0-473-01064-X

- ^ a b Bausani, A., Chapter 3 in Cambridge History of Iran (5), p. 289.

- ^ a b c d S. H. Nasr Chapter 9, p . 170-1

- ^ Dictionary of Minor Planet Names - p.255

References

- Turner, Howard R. (1997). Science in Medieval Islam: An Illustrated Introduction. University of Texas Press. ISBN 0292781490.

- Jos Biegstraaten (2008). "Omar Khayyam (His impact on the literary and social scene abroad)". Encyclopaedia Iranica. vol. 15. Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation. http://www.iranica.com/articles/khayyam-xi.

- Nasr, S. H. (2006). Islamic Philosophy from Its Origin to the Present: Philosophy in the Land of Prophecy. SUNY Press. ISBN 0791467996.

- Katz, Victor (1998). A History of Mathematics: An Introduction (2 ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 879. ISBN 0321016181.

- KnoebelNasr, Arthur; Laubenbacher, Reinhard; Lodder, Jerry; Pengelley, David (2007). Mathematical Masterpieces: Further Chronicles by the Explorers. Springer. ISBN 0387330615.

- The Cambridge History of Iran (5): The Saljug and Mongol Periods. Cambridge University Press. 1968. ISBN 052106936X.

- Smith, David Eugene (1935). "Euclid, Omar Khayyâm, and Saccheri". Scripta Mathematica III (1): 5–10. OCLC 14156259.

- Rozenfeld, Boris A. (1988). A History of Non-Euclidean Geometry: Evolution of the Concept of a Geometric Space. Springer Verlag. pp. 65, 471. ISBN 0-387-96458-4. http://books.google.com/books?id=DRLpAFZM7uwC&printsec=frontcover&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- E.G. Browne (1998). Literary History of Persia. (Four volumes, 2,256 pages, and 25 years in the writing). ISBN 0-7007-0406-X

- Jan Rypka (1968). History of Iranian Literature. Reidel Publishing Company. OCLC 460598. ISBN 90-277-0143-1

- Omar Khayyam: Vierzeiler (Rubāʿīyāt) übersetzt von Friedrich Rosen mit Miniaturen von Hossein Behzad. ISBN 978-3-86931-622-2 Details

External links

- Hashemipour, Behnaz (2007). "Khayyām: Ghiyāth al‐Dīn Abū al‐Fatḥ ʿUmar ibn Ibrāhīm al‐Khayyāmī al‐Nīshāpūrī". In Thomas Hockey et al. The Biographical Encyclopedia of Astronomers. New York: Springer. pp. 627–8. ISBN 9780387310220. http://islamsci.mcgill.ca/RASI/BEA/Khayyam_BEA.htm. (PDF version)

- Umar Khayyam, at the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Khayyam's works in original Persian at Ganjoor Persian Library

- Khayyam in Tarikhema.ir

- Listen to The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám audiobook at LibriVox

- The illustrated Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám at Internet Archive.

- Omar Khayyam's Rubaiyat as translated by Edward Fitzgerald – 1st edition

- The Rubaiyat by Omar Khayyam – The Internet Classics Archive

- Illustrations to the Rubaiyat by Adelaide Hanscom

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||