Propeller (aircraft)

| Propeller | |

|---|---|

| The feathered propellers of an RAF Hercules C.4 |

Aircraft propellers or airscrews[1] convert rotary motion from piston engines or turboprops to provide propulsive force. They may be fixed or variable pitch. Early aircraft propellers were carved by hand from solid or laminated wood with later propellers being constructed from metal. The most modern propeller designs use high-technology composite materials.

The propeller is usually attached to the crankshaft of a piston engine, either directly or through a reduction unit. Light aircraft engines often do not require the complexity of gearing but on larger engines and turboprop aircraft it is essential.

Contents |

History

The twisted airfoil (aerofoil) shape of modern aircraft propellers was pioneered by the Wright brothers. They realised that a propeller is essentially the same as a wing, and were able to use data from their earlier wind tunnel experiments on wings. They also realised that the angle of attack of the blades needed to vary along the length of the blade, thus it was necessary to introduce a twist along the length of the blades. Their original propeller blades were only about 5% less efficient than the modern equivalent, some 100 years later.[2]

Alberto Santos Dumont was another early pioneer, having designed propellers before the Wright Brothers (albeit not as efficient) for his airships. He applied the knowledge he gained from experiences with airships to make a propeller with a steel shaft and aluminium blades for his 14 bis biplane. Some of his designs used a bent aluminium sheet for blades, thus creating an airfoil shape. They were heavily undercambered, and this plus the absence of lengthwise twist made them less efficient than the Wright propellers. Even so, this was perhaps the first use of aluminium in the construction of an airscrew.

Theory and design of aircraft propellers

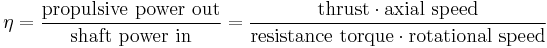

A well-designed propeller typically has an efficiency of around 80% when operating in the best regime.[3] Changes to a propeller's efficiency are produced by a number of factors, notably adjustments to the helix angle(θ), the angle between the resultant relative velocity and the blade rotation direction, and to blade pitch (where θ = Φ + α) . Very small pitch and helix angles give a good performance against resistance but provide little thrust, while larger angles have the opposite effect. The best helix angle is when the blade is acting as a wing producing much more lift than drag.

A propeller's efficiency is determined by

.

.

Propellers are similar in aerofoil section to a low-drag wing and as such are poor in operation when at other than their optimum angle of attack. Therefore a method is needed to alter the blades' pitch angle as engine speed and aircraft velocity are changed.

A further consideration is the number and the shape of the blades used. Increasing the aspect ratio of the blades reduces drag but the amount of thrust produced depends on blade area, so using high-aspect blades can result in an excessive propeller diameter. A further balance is that using a smaller number of blades reduces interference effects between the blades, but to have sufficient blade area to transmit the available power within a set diameter means a compromise is needed. Increasing the number of blades also decreases the amount of work each blade is required to perform, limiting the local Mach number - a significant performance limit on propellers.

A propeller's performance suffers as the blade speed nears the transonic. As the relative air speed at any section of a propeller is a vector sum of the aircraft speed and the tangential speed due to rotation, a propeller blade tip will reach transonic speed well before the aircraft does. When the airflow over the tip of the blade reaches its critical speed, drag and torque resistance increase rapidly and shock waves form creating a sharp increase in noise. Aircraft with conventional propellers, therefore, do not usually fly faster than Mach 0.6. There have been propeller aircraft which attained up to the Mach 0.8 range, but the low propeller efficiency at this speed makes such applications rare.

There have been efforts to develop propellers for aircraft at high subsonic speeds.[4] The 'fix' is similar to that of transonic wing design. The maximum relative velocity is kept as low as possible by careful control of pitch to allow the blades to have large helix angles; thin blade sections are used and the blades are swept back in a scimitar shape (Scimitar propeller); a large number of blades are used to reduce work per blade and so circulation strength; contra-rotation is used. The propellers designed are more efficient than turbo-fans and their cruising speed (Mach 0.7–0.85) is suitable for airliners, but the noise generated is tremendous (see the Antonov An-70 and Tupolev Tu-95 for examples of such a design).

Forces acting on a propeller

Five forces act on the blades of an aircraft propeller in motion, they are:[5]

- Thrust bending force

- Thrust loads on the blades act to bend them forward.

- Centrifugal twisting force

- Acts to twist the blades to a low or fine pitch angle.

- Aerodynamic twisting force

- As the centre of pressure of a propeller blade is forward of its centreline the blade is twisted towards a coarse pitch position.

- Centrifugal force

- The force felt by the blades acting to pull them away from the hub when turning.

- Torque bending force

- Air resistance acting against the blades, combined with inertial effects causes propeller blades to bend away from the direction of rotation.

Curved propeller blades

Since the 1940s, propellers and propfans with swept tips or curved "scimitar-shaped" blades have been studied for use in high-speed applications so as to delay the onset of shockwaves, in similar manner to wing sweepback, where the blade tips approach the speed of sound. The Airbus A400M turboprop transport aircraft is expected to provide the first production example: note that it is not a propfan because the propellers are not mounted direct on the engine shaft but are driven through reduction gearing.

Propeller control

Variable pitch

The purpose of varying pitch angle with a variable pitch propeller is to maintain an optimal angle of attack (maximum lift to drag ratio) on the propeller blades as aircraft speed varies. Early pitch control settings were pilot operated, either two-position or manually variable. Following World War I, automatic propellers were developed to maintain an optimum angle of attack. This was done by balancing the centripetal twisting moment on the blades and a set of counterweights against a spring and the aerodynamic forces on the blade. Automatic props had the advantage of being simple, lightweight, and requiring no external control, but a particular propeller's performance was difficult to match with that of the aircraft's powerplant. An improvement on the automatic type was the constant-speed propeller. Constant-speed propellers allow the pilot to select a rotational speed for maximum engine power or maximum efficiency, and a propeller governor acts as a closed-loop controller to vary propeller pitch angle as required to maintain the selected engine speed. In most aircraft this system is hydraulic, with engine oil serving as the hydraulic fluid. However, electrically controlled propellers were developed during World War II and saw extensive use on military aircraft, and have recently seen a revival in use on homebuilt aircraft.

Feathering

On some variable-pitch propellers, the blades can be rotated parallel to the airflow to reduce drag in case of an engine failure. This is called feathering. Feathering propellers were developed for military fighter aircraft prior to World War II, as a fighter is more likely to experience an engine failure due to the inherent danger of combat. On single-engined aircraft, whether a powered glider or turbine powered aircraft, the effect is to increase the gliding distance. On a multi-engine aircraft, feathering the propeller on a failed engine reduces drag, allowing the flight to continue with the remaining powerplant.

Most feathering systems for reciprocating engines sense a drop in oil pressure and move the blades toward the feather position, and require the pilot to pull the propeller control back to disengage the high-pitch stop pins before the engine reaches idle RPM. Turboprop control systems usually utilize a negative torque sensor in the reduction gearbox which moves the blades toward feather when the engine is no longer providing power to the propeller. Depending on design, the pilot may have to push a button to override the high-pitch stops and complete the feathering process, or the feathering process may be totally automatic.

Reverse pitch

In some aircraft, such as the C-130 Hercules, the pilot can manually override the constant-speed mechanism to reverse the blade pitch angle, and thus the thrust of the engine (although the rotation of the engine itself does not reverse). This is used to help slow the plane down after landing in order to save wear on the brakes and tires, but in some cases also allows the aircraft to back up on its own. See also Thrust reversal.

Contra-rotating propellers

Contra-rotating propellers use a second propeller rotating in the opposite direction immediately 'downstream' of the main propeller so as to recover energy lost in the swirling motion of the air in the propeller slipstream. Contra-rotation also increases power without increasing propeller diameter and provides a counter to the torque effect of high-power piston engine as well as the gyroscopic precession effects, and of the slipstream swirl. However on small aircraft the added cost, complexity, weight and noise of the system rarely make it worthwhile.

Counter-rotating propellers

Counter-rotating propellers are sometimes used on twin-, and other multi-engine, propeller-driven aircraft. The propellers of these wing-mounted engines turn in opposite directions from those on the other wing. Generally, the propellers on both engines of most conventional twin-engined aircraft spin clockwise (as viewed from the rear of the aircraft). Counter-rotating propellers generally spin clockwise on the left engine, and counter-clockwise on the right. The advantage of counter-rotating propellers is to balance out the effects of torque and p-factor, eliminating the problem of the critical engine.

Aircraft fans

A fan is a propeller with a large number of blades. A fan therefore produces a lot of thrust for a given diameter but the closeness of the blades means that each strongly affects the flow around the others. If the flow is supersonic, this interference can be beneficial if the flow can be compressed through a series of shock waves rather than one. By placing the fan within a shaped duct, specific flow patterns can be created depending on flight speed and engine performance. As air enters the duct, its speed is reduced while its pressure and temperature increase. If the aircraft is at a high subsonic speed this creates two advantages: the air enters the fan at a lower Mach speed; and the higher temperature increases the local speed of sound. While there is a loss in efficiency as the fan is drawing on a smaller area of the free stream and so using less air, this is balanced by the ducted fan retaining efficiency at higher speeds where conventional propeller efficiency would be poor. A ducted fan or propeller also has certain benefits at lower speeds but the duct needs to be shaped in a different manner than one for higher speed flight. More air is taken in and the fan therefore operates at an efficiency equivalent to a larger un-ducted propeller. Noise is also reduced by the ducting and should a blade become detached the duct would contain the damage. However the duct adds weight, cost, complexity and (to a certain degree) drag.

See also

References

- ^ "Airscrew." Oxford English Dictionary. Retrieved: 23 March 2011.

- ^ Ash, Robert L., Colin P. Britcher and Kenneth W. Hyde. "Wrights: How two brothers from Dayton added a new twist to airplane propulsion." Mechanical Engineering: 100 years of Flight, 3 July 2007.

- ^ Propeller Aircraft Performance and The Bootstrap Approach

- ^ Pushing The Envelope With Test Pilot Herb Fisher. Planes and Pilots of World War 2, 2000. Retrieved: 22 July 2011.

- ^ FAA 1976, p. 327.

- Airframe & Powerplant Mechanics Powerplant Handbook, U.S. Department of Transportation, 1976

External links

- Experimental Aircraft Propellers

- Basic information on the effects the prop has on basic flying

- HOWTO adjust a propeller correctly

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||