2010 Pacific hurricane season

| Season summary map | |

| First storm formed | May 29, 2010 |

|---|---|

| Last storm dissipated | December 22, 2010 |

| Strongest storm | Celia – 921 mbar (hPa) (27.21 inHg), 160 mph (260 km/h) |

| Total depressions | 13 |

| Total storms | 8 (record low) |

| Hurricanes | 3 (record low) |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 2 |

| Total fatalities | 199 direct, 44 indirect |

| Total damage | $1.6 billion (2010 USD) |

| Pacific hurricane seasons 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, Post-2011 |

|

| Related article | |

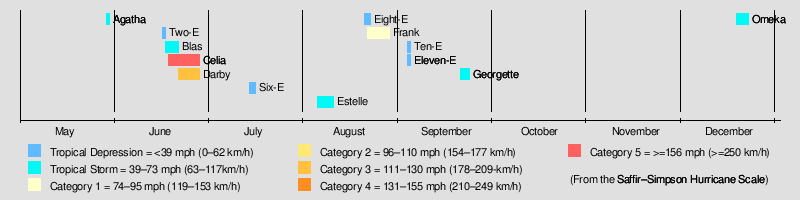

The 2010 Pacific hurricane season was the least active Pacific hurricane season, in terms of the number of named storms and hurricanes, on record, due to a moderate La Niña, unlike the 2010 Atlantic hurricane season, which was one of the most active on record. It officially started on May 15, 2010 for the eastern Pacific, and June 1, 2010 for the central Pacific, and officially ended on November 30, 2010. Unlike the 2009 season, the first storm of the 2010 season, Agatha, formed during the month of May. It developed on May 29 near the coast of Guatemala. In the second week of June, a sudden spree of tropical cyclones developed, and between June 16 and 22, four cyclones formed, including the first two major hurricanes of the season, Celia and Darby. However, following the record active June, July saw zero name storms. In August and September only 2 tropical storms and one hurricane formed. Tropical Depression Eleven-E caused a great deal of flooding in southern Mexico, causing millions of dollars in damage and causing over 50 deaths and $500 million in damage in areas of Oaxaca and Guatemala. Tropical Storm Omeka was a rare off-season storm.

Seasonal forecasts

| Source | Date | Named storms |

Hurricanes | Major hurricanes |

| Record high activity | 27 | 16 (Tie) | 10 | |

| Record low activity | 8 (Tie) | 3 | 0 (Tie) | |

| –––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––––– | ||||

| NOAA | Average[1] | 15.3 | 8.8 | 4.2 |

| NOAA | 1995-2008 average[1] | 14 | 7 | 3 |

| NOAA | 27 May 2010[1] | 9 - 15 | 4 - 8 | 1 - 3 |

On May 19, 2010, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released their forecast for the 2010 Central Pacific hurricane season, which would start on June 1. They expected two or three cyclones to form in or enter the region throughout the season, below the average of four or five storms. The below-average activity forecast was based on two factors: the first was the continuance of a period of decreased activity in the central Pacific; and second, the effects of a Neutral El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO) or La Niña, both of which reduce cyclone activity in the region. However, in light of the near-miss of Hurricane Felicia the previous year, forecasters at the Central Pacific Hurricane Center gave the public a basic message for the 2010 season, "Prepare! Watch! Act!".[2]

On May 27, 12 days after the official start of the 2010 eastern Pacific hurricane season, NOAA released their forecast for the basin. Similar to the forecast for the central Pacific, below-average activity was expected, with nine to fifteen named storms forming, four to eight of which would become hurricanes and a further one to three would become major hurricanes. This lessened activity was based on the same two factors as the central Pacific, decreased activity since 1995 and the ENSO event. Overall, NOAA stated there was a 75% chance of below-average activity, 20% of near-normal and only a 5% chance of above-average.[3]

Seasonal summary

| Month | Averages/Actual[nb 2] | ACE[nb 3] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Storms | Hurricanes | Major | Month | Year | |

| May | 1 (0-1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | - | - |

| June | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (0-1) | ~300% | >300% |

| July | 0 (3-4) | 0 (2) | 0 (1) | 0% | 107% |

| August | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | 0 (1) | 40% | 75% |

| September | 1 (3) | 0 (2) | 0 (1) | <5% | 46% |

| October | 0 (2) | 0 (1) | 0 (0-1) | 0% | 46% |

| November | 0 (0-1) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0% | ~46% |

| Total[4] | 7 (15) | 3 (9) | 2 (4) | - | ~46% |

Coinciding with pre-season forecasts,[1] the 2010 season was unusually quiet. However, it was less active than predicted as well, with a record low of eight named storms forming.[5] There was also a record-late December system, Tropical Storm Omeka, in the Central Pacific Hurricane Center's (CPHC) area of responsibility, though it was not factored in to the National Hurricane Center's (NHC) area of responsibly total.[4][6] Initially, the season began with record-high activity, featuring two major hurricanes in June. Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE)[nb 4] values exceeded 300% of the long-term mean, though most was due to Category 5 Hurricane Celia.[7] Hurricane Celia was also the second-earliest forming storm of that intensity during the course of a season, surpassed only by Hurricane Ava in 1973.[5] The month featured an ACE value of 37.22, eclipsing the previous record set in 1984.[7] However, this activity abruptly halted and languished throughout the month of July.[4][8] During that month, only one tropical depression formed; this marked the first time since 1966 that no named storms formed in the basin during the month of July.[5] However, due to the activity in June, the ACE value for the season by the start of August remained slightly above normal, roughly 107% the yearly mean.[8] From July 1 to the end of the season, the basin observed record low activity, with only three named storms developing.[9]

There were four tropical cyclones that impacted land in this season. The first was Tropical Storm Agatha, which brought catastrophic rainfall and flooding to Central America, especially Guatemala. Tens of thousands of structures were destroyed across four countries, leaving roughly $1.1 billion (2010 USD) in property damage and 317 fatalities. Tropical Depression Two-E caused only minor effects on land, bringing moderate rains and gusty winds to the Mexican state of Oaxaca. Tropical Depression 11-E caused a great deal of flooding in southern Mexico, causing millions of dollars in damage and causing over 50 deaths in areas of Oaxaca. And Tropical Storm Georgette made landfall in southern Baja California and Mainland Mexico, causing minor damage. Hurricane Celia became the first Category 5 hurricane of the season, and marked the first occasion when consecutive Pacific hurricane seasons had hurricanes of that intensity, following 2009's Hurricane Rick, and became only the second June Category 5 hurricane in the Eastern Pacific, after 1973's Ava.[10] Hurricane Darby was the second major hurricane of the season, reaching Category 3 strength on June 25. This made Darby the earliest second major hurricane of a season, eclipsing 1978's Hurricane Daniel, which reached major hurricane status on June 30.[11] However, after the very active June, there was a period of inactivity between July and early September, with only 2 named storms forming in the two-month period. September was the least active September since reliable records began in 1971 with the formation of only one tropical storm, Tropical Storm Georgette, which was partly due to the ongoing La Niña. There was a record low level of hurricanes and tropical storms. Initially, By the end of the season, the Central Pacific experienced no tropical cyclones; the last time this happened was in 1979.[12]

By the official end of the season, the Pacific had produced a record low of eight named storm, tying the previous in 1977.[5] In terms of ACE, the season was the third-quietest, only surpassed by the 2007 and 1977 seasons. Of this, roughly 70% was attributable to Hurricanes Celia and Darby.[4] The record inactivity experienced in the Northeastern Pacific also took place in the Northwestern Pacific. Since reliable records began in the 1970s, there has been no precedent for both basins experiencing exceptionally low tropical cyclone formation. Moreover, this general lack of storm formation was reflected in all cyclone basins except the Atlantic. On average, the Northeastern Pacific accounts for 16 percent of the world's storms; however, during 2010, it accounted for roughly 10 percent (7 out of 67 cyclones).[13]

Storms

Tropical Storm Agatha

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | May 29 – May 30 | ||

| Intensity | 45 mph (75 km/h) (1-min), 1001 mbar (hPa) | ||

Tropical Storm Agatha originated from an area of convection, or thunderstorms, that developed on May 24, off the west coast of Costa Rica.[14] At the time, there was a trough in the region that extended into the southwestern Caribbean Sea, associated with the Intertropical Convergence Zone.[15] The system drifted northwestward, and conditions favored further development.[16] On May 25, the convection became more concentrated, and the National Hurricane Center (NHC) noted the potential for a tropical depression to develop.[17] The next day, it briefly became disorganized,[18] as its circulation was broad and elongated; however, the disturbance was in a very moist environment, and multiple low level centers gradually organized into one.[19] The low continued to get better organized;[20] however, there was a lack of a well-defined circulation.[21] On May 29, after further organization of the circulation and convection, the NHC initiated advisories on Tropical Depression One-E while the system was located about 295 miles (475 km) west of San Salvador, El Salvador.[22] Later that morning, the depression strengthened into a tropical storm and was named Agatha. Agatha made landfall that afternoon near Champerico, Guatemala with winds of 45 mph (75 km/h). Agatha then weakened into a tropical depression during that evening. Early on the morning of May 30, Agatha degenerated into a remnant low before dissipating hours later. The following day, the remnants of Agatha may have redeveloped a surface low in the northwestern Caribbean Sea; however, this feature was short-lived.[23]

Although a weak tropical cyclone, Agatha brought torrential rainfall to much of Central America.[24] According to Guatemala's president, Álvaro Colom, some areas received more than 1 m (3.3 ft) of rain.[25] Throughout Guatemala, a total of 287 people were killed by the storm.[26] Additionally, damage amounted to $982 million, making it one of the costliest eastern Pacific tropical cyclones on record.[27] In El Salvador, 11 people were killed and damage from the storm reached $112.1 million.[26] Honduras also suffered significant losses from the storm. Throughout the country, 18 people were killed and damage was estimated at $530 million.[28] One person was also killed in Nicaragua.[26]

A burst of convection re-emerged east of Belize, in the Atlantic basin, on May 31. On June 1, the National Hurricane Center stated that the remnants of Tropical Storm Agatha had only a low chance of regeneration in the western Caribbean Sea.[29] By the next day, the thunderstorm activity associated with Agatha in the western Caribbean had dissipated. However, the remnans of Tropical Storm Agatha persisted until June 6, causing death and destruction over Central America. On June 6, the remnants of Tropical Storm Agatha dissipated completely, after ravaging the Honduras and El Salvador.

In all, Agatha caused 317 fatalities, and roughly $1.1 billion in damage throughout Central America.[26]

Tropical Depression Two-E

| Tropical depression (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | June 16 – June 17 | ||

| Intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min), 1007 mbar (hPa) | ||

During early June, a tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa and entered the Atlantic Ocean. Tracking westward, the system eventually reached the eastern Pacific on June 13. As it approached the Gulf of Tehuantepec, convection increased,[30] despite strong wind shear.[31] Early on June 16, sufficient development had taken place for the NHC to classify the wave as a tropical depression, at which time the depression was situated roughly 110 mi (175 km) south of Salina Cruz, Mexico. After attaining its peak intensity with winds of 35 mph (55 km/h) and a pressure 1007 mbar (hPa; 29.74 inHg).[30] The next day, organization decreased as strong wind shear took its toll on the system. However, the NHC was still predicting the system to become a tropical storm.[32] According to satellite imagery, the depression dissipated early on June 17;[30] however, operationally, the NHC continued advisories on the depression for an additional 15 hours.[33]

Due to its proximity to land, tropical storm watches and warnings were issued in advance of the storm when the system was first classified. This was discontinued when the system dissipated.[30] The NHC also noted the possibility of 4 in (100 mm) to 12 in (300 mm) of rain over the high mountains of Mexico.[34] The Civil Protection, a part of the local government, issued a high alert late on June 16 for the Oaxaca coast.[35] In addition, the public was urged to take precautions.[36] Extreme caution was recommended for shipping vessels.[37] Rainfall associated with the depression extended as far north as Oaxaca. In San Juan Bautista Tuxtepec, 82 homes were damaged by flood waters and 40 others were affected in the town of Zimatlán de Alvarez.[38] Some homes lost their roofs and a few trees were downed as a result of high winds.[39]

Tropical Storm Blas

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | June 17 – June 21 | ||

| Intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min), 994 mbar (hPa) | ||

On May 30, a new tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa and entered the Atlantic Ocean. Little convective development took place as it traversed the region; however, as it crossed Central America between June 9 and 10, it began to show signs of strengthening. By June 13, an area of low pressure developed within the wave and slowly developed a surface circulation over the following 48 hours as it remained nearly stationary over open waters. Early on June 17, deep convection was able to maintain itself over the system, prompting the NHC to classify the low as Tropical Depression Three-E; at this time, the depression was situated 305 mi (490 km) south-southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico. Within hours of becoming a tropical depression, a ship in the region reported sustained winds of 45 mph (75 km/h), indicating that the system had developed into a tropical storm. The newly upgraded storm, now named Blas by the NHC, began to track slowly to the northwest, and later nearly due west, in response to a strengthening ridge over Mexico.[40]

Strong wind shear prevented Blas from strengthening further over the following day; however, by June 19, the system entered a region of weaker shear. This allowed convection to develop over the center of circulation and that afternoon, the storm attained its peak intensity with winds of 65 mph (100 km/h) and a pressure of 992 mbar (hPa; 29.29 inHg). Shortly thereafter, cooler sea surface temperatures took their toll on Blas, causing the storm to gradually weaken. By June 21, the system weakened to a tropical depression as convection diminished. Hours later, it degenerated into a non-convective remnant low while situated about 715 mi (1,150 km) west-southwest of the southern tip of Baja California Sur. The remnants of Blas persisted through June 23 as they continued westward before it dissipated to a weak upper-level low.[40]

Hurricane Celia

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | June 18 – June 28 | ||

| Intensity | 160 mph (260 km/h) (1-min), 921 mbar (hPa) | ||

Celia formed out of a tropical wave on June 18, quickly organized into a tropical storm, and later into a hurricane the following day as deep convection consolidated around the center. On June 21, the storm further intensified into a Category 2 hurricane; however, over the following days, Celia's winds fluctuated. The system briefly attained major hurricane status on June 23 before temporarily succumbing to wind shear. Once this shear lightened the next day, Celia rapidly intensified to attain its peak intensity with winds of 160 mph (260 km/h) and an estimated barometric pressure of 921 mbar (hPa; 27.20 inHg).[41]

Not long after reaching this strength, wind shear increased and the system entered a dry, stable environment. Over the following 42 hours, sustained winds decreased to tropical storm force and the system began to stall over the open ocean by June 27. Despite highly unfavorable conditions, the storm managed to retain tropical storm status through June 28 and degenerated into a non-convective remnant low that evening. The remnants of Celia continued to drift towards the north before finally dissipating on June 30, about 990 mi (1,590 km) southwest of the southern tip of Baja California Sur.[41]

Hurricane Darby

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | June 23 – June 28 | ||

| Intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min), 959 mbar (hPa) | ||

The second, and final, major hurricane of the season, Hurricane Darby originated from a vigorous tropical wave that moved off the west coast of Africa on June 8. Initially well-organized, the wave rapidly deteriorated within 24 hours; it continued westward without redevelopment and entered the Eastern Pacific on June 19. The following day, an area of low pressure developed within the system as it slowed and turned towards the west-northwest. Gradually organizing, the low strengthened into a tropical depression on June 23 while situated roughly 380 mi (610 km) south-southeast of Salina Cruz, Mexico. Over the following two days, Darby underwent two periods of rapid intensification. At the end of the second phase on June 25, the storm attained its peak intensity as a Category 3 hurricane with winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) and a pressure of 959 mbar (hPa; 28.32 inHg). Though a strong strom, Darby was unusually small with tropical storm force winds extending only 70 mi (110 km) from its center.[42]

Not long after peaking, a large area of westerly winds, produced by Hurricane Alex over the Gulf of Mexico, caused Darby to stall offshore before turning to the east, being drawn into the circulation of the larger storm. Increased wind shear produced by the "massive outlfow of Alex" caused the small storm to rapidly weaken. By June 28, Darby had diminished to a tropical depression and later to a remnant low off the coast of Mexico. The low persisted for another day before fully dissipating offshore.[42]

While offshore, authorities in Mexico advised residents to be cautious of heavy rains from Darby. Alerts were issued for several areas; however, the storm dissipated before reaching land.[43][44] The combined effects of Hurricanes Alex and Darby resulted in heavy rains over much of Chiapas, amounting to 12 to 16 in (300 to 410 mm) in some areas. Flash flooding damaged 43 homes and affected 60,000 people.[45]

Tropical Depression Six-E

| Tropical depression (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | July 14 – July 16 | ||

| Intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min), 1006 mbar (hPa) | ||

On July 11, a low pressure formed southwest of Central America.[46] The next day, the system began to organize.[47] After a decrease in convection,[48] the system became more concentrated.[49] After additional development, the NHC upgraded the disturbance into Tropical Depression Six-E on July 14.[46] Six-E slowed down forward momentum, and slowly turned north. The depression did not develop further and degenerated into an area of low pressure on July 16.

Though relatively far from land, the depression's outer bands brought locally heavy rains to portions of Colima and Jalisco.[50]

Tropical Storm Estelle

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 4 – August 10 | ||

| Intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min), 994 mbar (hPa) | ||

After an unusual, record inactive July, an area of disturbed weather formed off the south coast of Mexico, on August 4 from a tropical wave that left Africa 13 days earlier.[51] The system became better organized throughout the next day, and was upgraded into a tropical depression on August 6, 138 mi (222 km) southwest of Acapulco, Mexico. Initially, there was uncertainty regarding the storm's path.[52] It reached tropical storm status on the same day. On August 8, the storm showed signs of weakening. It was downgraded into a tropical depression the next day. Estelle became a remnant low on August 10, dissipating shortly thereafter.[51]

Though the center of Estelle remained offshore, its outer bands brought moderate to heavy rains and increased surf to coastal areas of Guerrero, Michoacán, Colima, and Jalisco on August 7.[53] The following day, a detachment of clouds associated with the storm brought locally heavy rains to Mazatlán, resulting in localized street flooding.[54]

Tropical Depression Eight-E

| Tropical depression (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 20 – August 21 | ||

| Intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min), 1003 mbar (hPa) | ||

On August 3, a tropical wave moved off the west coast of Africa and tracked westward across the Atlantic Ocean. By August 15, the wave crossed Central America and entered the Eastern Pacific. Over the following five days, development was relatively slow at first, resulting in forecasters at the NHC not predicting the system to become a tropical cyclone. However, on August 20, a low pressure area formed and quickly became a tropical depression. At this time, the system was situated roughly 185 mi (295 km) west-southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico. Tracking northwestward in response to a mid-level ridge over northwestern Mexico, the depression moved through a region of moderate wind shear, preventing further development. Once over cooler waters on August 21, convection began to wane and the system degenerated into a remnant low later that day. Continuing along the same path, the remnants of the depression dissipated early on August 23 over open waters.[55]

Hurricane Frank

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 21 – August 28 | ||

| Intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min), 978 mbar (hPa) | ||

The wave that became Frank was first noticed on August 15 south of the Windward Islands. Tropical Depression Nine-E formed on August 21 south of the Gulf of Tehuantepec. It developed into a tropical storm the following morning. On August 23, Frank continued to intensify, but later faced shear and entered a period of weakening. However, on August 24, as shear decreased, it began to reorganize and strengthen again, becoming a hurricane on August 25. Frank also formed an eye feature that persisted for about a day. Two days later, Frank weakened back into a tropical storm. Frank encountered unfavorable conditions of high shear and cool waters, causing it to rapidly weakening overnight. Frank became a remnant low on August 28.

In Mexico, six deaths were reported. A total 30 homes were destroyed with 26 others damaged. Two major roads were damaged with another road blocked due to a landslides. Several rivers overflowed their banks as well.[56] In the wake of the storm, 110 communities requested assistance from the government. By September 14, an estimated 200,000 food packages were distributed to the region. Losses from Hurricane Frank exceeded 100 million pesos ($8.3 million USD).[57]

Tropical Depression Ten-E

| Tropical depression (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | September 3 – September 4 | ||

| Intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min), 1003 mbar (hPa) | ||

Tropical Depression Ten-E originated from a tropical wave that moved off the west coast of Africa on August 14. Tracking westward, the wave eventually crossed Central America and entered the Pacific Ocean on August 26. Gradual organization took place by early September as deepening convection. During September 3, a low-level circulation developed within the system and the NHC classified it as a tropical depression. At this time, the depression was situated roughly 255 mi (410 km) south-southeast of the southern tip of Baja California Sur. Located between a strong ridge over Mexico and trough over the north Pacific Ocean, the system tracked northwestward throughout the remainder of its existence. Maximum sustained winds never exceeded 35 mph (55 km/h) before moving into a region cooler waters and moderate wind shear. The combination of these two factors caused convection to diminish; the depression degenerated into a non-convective remnant low on September 4 before dissipating the following day.[58]

Tropical Depression Eleven-E (Hermine)

| Tropical depression (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | September 3 – September 4 | ||

| Intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min), 1004 mbar (hPa) | ||

During mid-August, a westward moving tropical wave in the Atlantic Ocean spawned Hurricane Danielle.[59] The southern portion of this system continued its track and later entered the Eastern Pacific on August 29. By September 2, convection consolidated over the Gulf of Tehuantepec and a low-level circulation developed as it moved in a general northward direction. Classified a tropical depression the following day,[60] the National Hurricane Center initially expected it to attain tropical storm status before moving over land.[61] A ship in the region measued gale-force winds, supporting this forecast but later analysis revealed that these winds were associated with a broad monsoon trough which the depression was embedded within. Failing to intensify, the system made landfall near Salina Cruz, Mexico and rapidly weakened. Maintaining its circulation, the depression survived its crossing of Mexico and regenerated into Atlantic Tropical Storm Hermine. The crossover of this storm is regarded as an uncommon occurrence,[60] taking place only a handful of times since reliable records in the Atlantic began in 1851.[62]

Due to the depression's proximity to land, tropical storm warnings were issued for southern Mexico. Little damage is directly attributed to the system but the overall trough which it was embedded within produced torrential rains over Guatemala and Costa Rica.[60] At least 44 people were killed throughout the country, mainly from a series of landslides along the Inter-American Highway.[63] Damage is estimated to be at least $500 million.[26] Additionally, three people were killed in Costa Rica.[64]

Tropical Storm Georgette

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | September 20 – September 23 | ||

| Intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min), 999 mbar (hPa) | ||

Georgette originated from a tropical wave that moved off the west coast of Africa on September 1. Tracking westward across the Atlantic, the wave eventually spawned an area of low pressure, which developed into Hurricane Karl on September 14. The wave itself continued through the Caribbean Sea, and entered the Eastern Pacific on September 17, but signification development was not anticipated. Tracking northwestward, the low gradually organized into a tropical depression by September 20, at which time it was situated south of Baja California Sur. Shortly thereafter, it intensified into a tropical storm and was named Georgette. On September 21, Georgette attained its peak intensity with winds of 40 mph (65 km/h) and a minimum pressure of 999 mbar (hPa; 29.50 inHg). The storm struck Baja California Sur later that day before weakening to a tropical depression. It continued north as a depression and made landfall on mainland Mexico on September 22. The system dissipated over northern Mexico early on September 23.[65]

Tropical Storm Omeka

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | December 18 – December 22 | ||

| Intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min), 997 mbar (hPa) | ||

On December 16, an extratropical cyclone over the Northern Pacific Ocean began showing signs of tropical cyclogenesis. Drifting southeastward around the International Dateline, the system developed into a subtropical depression within the Central Pacific basin on December 18, becoming the latest-forming system east of 180° and north of the equator in the Pacific Ocean on record. Turning southwest, the system intensified into a subtropical storm later that day before crossing into the Western Pacific. While west of the dateline, the system attained its peak intensity with winds of 60 mph (95 km/h). Gaining more tropical characteristics, the storm transitioned into a fully tropical system a few hours after crossing the dateline for a third time. Upon doing so, it was recognized by the Central Pacific Hurricane Center and given the name Omeka. Turning to the northeast, gradual weakening took place over the following days, before Omeka dissipated north of the Hawaiian Islands, on December 22.[5]

Storm names

The following names were used for named storms that formed in East Pacific in 2010. Retired names, if any, will be announced by the World Meteorological Organization in the spring of 2011. This is the same list used in the 2004 season.[66] In March 2011, the World Meteorological Organization announced that it would not retire any names. This list will be re-used during the 2016 Pacific hurricane season.[67]

|

|

For the central Pacific Ocean, four consecutive lists are used, with the names used sequentially until exhausted, rather than until the end of the year, due to the low number of storms each year. Only one name, Omeka, was used during the course of the year.[66]

Season effects

This is a table of the storms and their effects in the 2010 Pacific hurricane season. This table includes the storm's names, duration, peak intensity, Areas affected (bold indicates made landfall in that region at least once), damages, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but are still storm-related. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave or a low. All of the damage figures are in 2010 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson Hurricane Scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category

at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (millions USD) |

Deaths | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agatha | May 29 – 30 | Tropical storm | 45 (75) | 1001 | Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, Chiapas, El Salvador, Belize | 1,100 | 190 | |||

| Two-E | June 16 – 17 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1007 | Oaxaca | N/A | 0 | |||

| Blas | June 17 – 21 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 992 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Celia | June 18 – 28 | Category 5 hurricane | 160 (260) | 921 | Oaxaca, Guerrero | None | 0 | |||

| Darby | June 23 – 28 | Category 3 hurricane | 120 (195) | 959 | Chiapas | N/A | 0 | |||

| Six-E | July 14 – 16 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1006 | Colima, Jalisco | None | 0 | |||

| Estelle | August 5 – 10 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 994 | Guerrero, Michoacán, Colima, Jalisco, Sinaloa | None | 0 | |||

| Eight-E | August 20 – 22 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1003 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Frank | August 21 – 28 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 978 | Tabasco, Oaxaca | 8.3 | 6 | |||

| Ten-E | September 3 – 4 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1000 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Eleven-E | September 3 – 4 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1005 | Oaxaca, Guatemala, Costa Rica | 500 | 3 (44) | |||

| Georgette | September 20 – 23 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 999 | Baja California Sur, Sonora, Sinaloa | N/A | 0 | |||

| Omeka | December 18 – 22 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 997 | None | None | 0 | |||

| Season Aggregates | ||||||||||

| 13 cyclones | May 29 – December 22 | 160 (260) | 921 | 1,608.3 | 199 (44) | |||||

See also

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- List of Pacific hurricane seasons

- 2010 Atlantic hurricane season

- 2010 Pacific typhoon season

- 2010 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 2009-10, 2010–11

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 2009-10, 2010–11

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 2009-10, 2010–11

References

- ^ a b c d Climate Prediction Center, NOAA (May 21, 2009). "NOAA: 2008 Tropical Eastern North Pacific Hurricane Outlook". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.webcitation.org/5hSA3PQ4z. Retrieved June 11, 2009.

- ^ Delores Clark (May 19, 2010). "NOAA Expects Below Normal Central Pacific Hurricane Season" (PDF). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.weather.gov/hawaii/pages/examples/2010cphc.pdf. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ Gerald Bell; Jae Schemm, Eric Blake, Todd Kimberlain, and Christopher Landsea (May 27, 2010). "2010 Eastern Pacific Hurricane Season Outlook". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Archived from the original on May 29, 2010. http://www.webcitation.org/5q5TZ41Ky. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ a b c d John P. Cangialosi and Stacy Stewart (February 28, 2011). "2010 Eastern Pacific Hurricane Season" (PPTX). Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorology. http://www.ofcm.gov/ihc11/Presentations/Session02%20-%20Season%20in%20Review/s02-02cangialosi.pptx. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Hurricane Research Division (March 2011). "Eastern Pacific HURDAT: 1949-2010". National Hurricane Center. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/hurdat/tracks1949to2010_epa.html. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ Raymond Tanabe (February 28, 2011). "Review of the 2010 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season and Preliminary Verification" (PPTX). Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorology. http://www.ofcm.gov/ihc11/Presentations/Session02%20-%20Season%20in%20Review/s02-04CPHC_2011_IHC.pptx. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ a b Eric S. Blake (July 1, 2010). "Eastern Pacific Monthly Tropical Weather Summary for June 2010". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2010/tws/MIATWSEP_jun.shtml?. Retrieved July 3, 2010.

- ^ a b Stacey Stewart, Todd Kimberlain and Jack L. Beven (August 1, 2010). "Eastern Pacific Monthly Tropical Weather Summary for July 2010". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2010/tws/MIATWSEP_jul.shtml?. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- ^ Todd Kimberlain, Eric Blake, Stacy Stewart and Robbie Berg (November 1, 2010). "Eastern Pacific Monthly Tropical Weather Summary for October 2010". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2010/tws/MIATWSEP_oct.shtml?. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ "Eastern Pacific hurricane best track analysis 1949-2009". National Hurricane Center. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. May 1, 2010. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/tracks1949to2009_epa.txt. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- ^ Eric Blake (June 25, 2010). "Hurricane Darby Discussion Twelve". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2010/ep05/ep052010.discus.012.shtml?. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

- ^ "Annual Archives". Central Pacific Hurricane Center. 2010. http://www.prh.noaa.gov/cphc/summaries/. Retrieved November 30, 2010.

- ^ Jeff Masters (April 4, 2011). "The global tropical cyclone season of 2010: record inactivity". Weather Underground. http://www.wunderground.com/blog/JeffMasters/comment.html?entrynum=1776. Retrieved April 4, 2011.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila and Eric S. Blake (May 24, 2010). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/text/TWOEP/TWOEP.201005242339.txt. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ Dave Sandoval (May 28, 2010). "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/text/TWDEP/TWDEP.201005241516.txt. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ Lixion A. Avila (May 25, 2010). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/text/TWOEP/TWOEP.201005252331.txt. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ John Cangialosi and Richard J. Pasch (May 26, 2010). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/text/TWOEP/TWOEP.201005261134.txt. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ Daniel Brown and David Roberts (May 27, 2010). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/text/TWOEP/TWOEP.201005272345.txt. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ Scott Stripling (May 27, 2010). "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/text/TWDEP/TWDEP.201005271607.txt. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ David Brown and Stacey Stewert (May 28, 2010). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/gtwo/epac/201005281740/index.php?basin=epac¤t_issuance=201005281740. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ^ Lixion A. Aliva and John Cangialosi (5-28-2010). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/gtwo/epac/201005282333/index.php?basin=epac¤t_issuance=201005282333. Retrieved 5-29-2010.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (May 29, 2010). "Tropical Depression One-E Special Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2010/ep01/ep012010.discus.001.shtml?. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- ^ John L. Beven II (August 13, 2010). "Tropical Storm Agatha Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-EP012010_Agatha.pdf. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ Juan Carlos Llorca (May 31, 2010). "Tropical Storm Agatha kills 142 in Central America". Associated Press. Yahoo! News. http://news.yahoo.com/s/ap/20100531/ap_on_re_la_am_ca/tropical_weather. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ Staff Writer (May 31, 2010). "Agatha storm deaths rise across Central America". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/world/latin_america/10195619.stm. Retrieved June 21, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "International Disaster Database: Disaster List". Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters. 2010. http://www.emdat.be/disaster-list. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ Staff writer (June 6, 2010). "Gobierno de Guatemala sigue evaluando daños, mientras muertos aumentan a 172" (in Spanish). NTN24. EFE. http://www.ntn24.com/content/gobierno-guatemala-sigue-evaluando-danos-mientras-muertos-aumentan-a-172. Retrieved 2010-06-08.

- ^ (Spanish) Staff Writer (June 2, 2010). "Tegucigalpa necesita L 10 mil millones para recuperarse". La Prensa. http://www.webcitation.org/5qILjW55g. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ John Cangialosi and James Franklin (June 1, 2010). "Atlantic Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/text/refresh/MIATWOAT+shtml/011733.shtml. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ^ a b c d Michael J. Brennan (July 28, 2010). "Tropical Depression Two-E Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-EP022010_Two-E.pdf. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ Staff Writer (June 12, 2010). "Tropical Weather Discussion". National Hurricane Center. https://listserv.illinois.edu/wa.cgi?A2=ind1006b&L=wx-tropl&T=0&X=558D791777B97BA4EA&P=29813. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Stacy Stewart/Lixon Avila (June 17, 2010). "Tropical Depression Two-E Discussion 4". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2010/ep02/ep022010.discus.004.shtml?. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ Daniel Brown (June 17, 2010). "Tropical Depression Two-E Public Advisory Five". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2010/ep02/ep022010.public.005.shtml?. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain and Daniel Brown (June 16, 2010). "Tropical Depression Two-E Public Advisory One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2010/ep02/ep022010.public.001.shtml?. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ Staff Writer (June 16, 2010). "Tropical Depression Two-E will cause heavy rain". Spanish: Acapulco News. http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&langpair=es. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Staff Writer (June 16, 2010). "Alert for Tropical Depression Two-E". Elecne De La Costa. http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&langpair=es. Retrieved June 16, 2010.

- ^ Staff Writer (June 16, 2010). "Tropical Depression Two-E stalks Oaxaca". National Hurricane Center. http://translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&langpair=es. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ (Spanish) Jimenez Luna (June 17, 2010). "Depresión Tropical 2-E se dirige a Guerrero". Noticias. http://bbmnoticias.com/index2.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=20426&pop=1&page=0&Itemid=1. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ (Spanish) Oscar Rodríguez (June 17, 2010). "Más de 150 damnificados en Oaxaca por depresión tropical 2-E". Milenio. http://www.webcitation.org/5qYukd3wN. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Robbie Berg (July 31, 2010). "Tropical Storm Blas Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-EP032010_Blas.pdf. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Todd B. Kimberlain (October 6, 2010). "Hurricane Celia Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-EP042010_Celia.pdf. Retrieved December 1, 2010.

- ^ a b Stacy R. Stewart (November 18, 2010). "Hurricane Darby Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-EP052010_Darby.pdf. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ (Spanish) Unattributed (June 25, 2010). "Alerta en cuatro estados por huracán ‘‘Darby’’". Informador. http://www.informador.com.mx/mexico/2010/212757/6/alerta-en-cuatro-estados-por-huracan-darby.htm. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ (Spanish) Agence-France-Presse and Reuters (June 25, 2010). "Huracán Darby sube a nivel 3 frente a costas mexicanas". La Prensa. http://www.oem.com.mx/laprensa/notas/n1685309.htm. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ (Spanish) Óscar Gutiérrez (June 26, 2010). "'Darby' y 'Alex' provocan primeras inundaciones". El Universal. http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/notas/690614.html. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ a b Stewart (July 11, 2010). "Tropical Weather Outlook". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/gtwo/epac/201007111803/index.php?basin=epac¤t_issuance=201007111803. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ Chirs Landesa; Stewart (July 12, 2010). "Tropical Weather Outlook (2)". NOAA. National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/gtwo/epac/201007121743/index.php?basin=epac¤t_issuance=201007121743. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ Robbie Breg (July 12, 2010). "Tropical Weather Outlook (3)". National Hurricane center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/gtwo/epac/201007130557/index.php?basin=epac¤t_issuance=201007130557. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ Robbie Berg (July 13, 2010). "Tropical Weather Outlook (4)". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/gtwo/epac/201007140557/index.php?basin=epac¤t_issuance=201007140557. Retrieved July 15, 2010.

- ^ (Spanish) Notimex (July 15, 2010). "Depresión tropical afectará Colima y Jalisco". El Universal. http://www.eluniversal.com.mx/notas/695800.html. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ a b Eric Blake. "Tropical Cyclone Report - Estelle". National Hurricane center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-EP072010_Estelle.pdf.

- ^ John Brown (8-5-2010). "Tropical Depression Seven-E Discussion". Natioanl Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2010/ep07/ep072010.discus.001.shtml?. Retrieved 8-5-2010.

- ^ (Spanish) Notimex (August 7, 2010). "Afectará Estelle Guerrero, Michoacán, Colima". Noticias MVX. http://www.noticiasmvs.com/Afectara-Estelle-Guerrero-Michoacan-Colima.html. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ (Spanish) Manuel Guízar (August 8, 2010). "Empapan lluvias de "Estelle" a Mazatlán". Noroeste. http://www.noroeste.com.mx/publicaciones.php?id=608041. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ Richard J. Pasch (January 24, 2011). "Tropical Depression Eight-E Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-EP082010_Eight-E.pdf. Retrieved March 23, 2011.

- ^ (Spanish) IRZA (August 2010). "Estiman que "Frank" dejó daños por $14 millones". El Sol de Chilpancingo. http://www.elsoldechilpancingo.com.mx/index.php/portada/9382-estiman-que-frank-dejo-danos-por-14-millones. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ (Spanish) Sandra Pacheco (September 14, 2010). "Necesarios más de 100 mdp para atender emergencia: URO". CNX Oaxaca. http://cnxoaxaca.com/?mod=noticias&i=6930&is=5. Retrieved March 22, 2011.

- ^ John P. Cangialosi (October 28, 2010). "Tropical Depression Ten-E Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-EP102010_Ten-E.pdf. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

- ^ Todd B. Kimberlain (December 15, 2010). "Hurricane Danielle Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-AL062010_Danielle.pdf. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ a b c John L. Beven II (December 6, 2011). "Tropical Depression Eleven-E Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-EP112010_Eleven-E.pdf. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ Robbie Berg and Michael Brennan (September 3, 2010). "Tropical Depression Eleven-E Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2010/ep11/ep112010.discus.001.shtml?. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ Hurricane Research Division (2010). "Easy-to-Read HURDAT (1851-2009)". National Hurricane Center. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/hurdat/easyread-2010.html. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ Staff Writer (September 6, 2010). "Guatemala declares day of mourning". Al Jazeera. http://english.aljazeera.net/news/americas/2010/09/2010966543602485.html. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ (Spanish) Solange Garrido (September 4, 2010). "Tres muertos en Costa Rica tras deslizamiento de tierra por fuertes lluvias". Radio Bio Bio. http://www.radiobiobio.cl/2010/09/04/tres-muertos-en-costa-rica-tras-deslizamiento-de-tierra-por-fuertes-lluvias/. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ Michael J. Brennan (November 4, 2010). "Tropical Storm Georgette Tropical Cyclone Report" (PDF). National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pdf/TCR-EP122010_Georgette.pdf. Retrieved March 9, 2011.

- ^ a b National Hurricane Center (January 8, 2010). "Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Names". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/aboutnames.shtml. Retrieved June 24, 2010.

- ^ Dennis Feltgen (March 16, 2011). "Two Tropical Cyclone Names Retired from List of Atlantic Storms". National Hurricane Center. http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2011/20110316_hurricanenames.html. Retrieved March 21, 2011.

Notes

- ^ Values are only for the Eastern Pacific (east of 140°W).

- ^ Storm averages are those in parenthesis.

- ^ Percentage of average ACE through the end of the month

- ^ Accumulated Cyclone Energy, broadly speaking, is a measure of the power of a hurricane multiplied by the length of time it existed, so storms that last a long time, as well as particularly strong hurricanes, have high ACEs.

External links

|

|

|||||