1950 Atlantic hurricane season

| Season summary map | |

| First storm formed | August 12, 1950 |

|---|---|

| Last storm dissipated | November 13, 1950 |

| Strongest storm | Dog – 185 mph (295 km/h) |

| Total depressions | 16 |

| Total storms | 16 |

| Hurricanes | 11 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 8 (record) |

| Total fatalities | 88 overall |

| Total damage | $38.5 million (1950 USD) |

| Atlantic hurricane seasons 1948, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1952 |

|

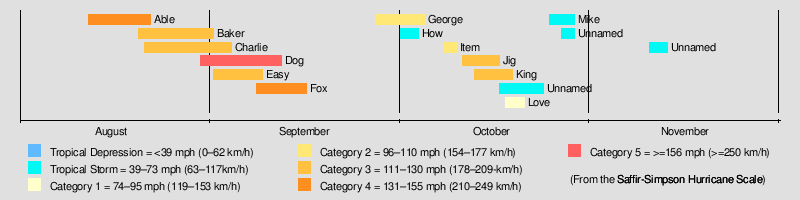

The 1950 Atlantic hurricane season was the first year in which tropical cyclones were given official names in the Atlantic basin. Names were taken from the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet, with the first named storm being designated "Able", the second "Baker", and so on. It was an active season with sixteen tropical storms, with all but two developing into hurricanes. Eight of these hurricanes were intense enough to be classified as major hurricanes—a denomination reserved for storms that attained sustained winds equivalent to a Category 3 or greater on the present-day Saffir-Simpson scale. The high number of major hurricanes make 1950 the holder of the record for the most systems of such intensity in a single season. One storm, the twelfth of the season, was unnamed and was originally excluded from the yearly summary. The large quantity of strong storms during the year yielded the highest seasonal accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) of the 20th century, and 1950 held the seasonal ACE record until broken by the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season.

The tropical cyclones of the season produced a total of 88 fatalities and $38.5 million in property damage (1950 USD, $351 million 2012 USD). The first officially named Atlantic hurricane was Hurricane Able, which formed on August 12, brushed the North Carolina coastline, and later moved across southeastern Canada. The strongest hurricane of the season, Hurricane Dog reached the equivalent of a Category 5 hurricane on the Saffir-Simpson scale, and caused extensive damage to the Leeward Islands. Two major hurricanes affected Florida: Easy produced the largest 24-hour rainfall total recorded in the United States, while King struck downtown Miami and caused $27.75 million (1950 USD, $253 million 2012 USD) of damage. The last storm of the year, Hurricane Love, dissipated on October 21 after striking the Florida Panhandle and causing minimal damage.

Contents |

Summary

| Most intense Atlantic hurricane seasons (since 1850)[nb 1] |

||

|---|---|---|

| Rank | Season | ACE |

| 1 | 2005 | 248 |

| 2 | 1950 | 243 |

| 3 | 1893 | 231 |

| 4 | 1995 | 227 |

| 5 | 2004 | 224 |

| 6 | 1926 | 222 |

| 7 | 1933 | 213 |

| 8 | 1961 | 205 |

| 9 | 1955 | 199 |

| 10 | 1887 | 182 |

The season officially began on June 15 and ended on November 15; these dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the Atlantic basin. This season was the first time that the United States Weather Bureau operated with radar technology to observe hurricanes 200 mi (320 km) away from land. Although the season began on June 15, most seasons do not experience tropical activity before August.[2] The tropics remained tranquil through early August, and the U.S. Weather Bureau noted that the season had been "remarkably quiet".[3] The inactive period soon ended on August 12, when the first tropical storm developed east of the Lesser Antilles. This storm received the name "Able" as part of the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet.[3] (The same alphabet was also used in the 1951 and 1952 seasons, before being replaced by female naming in 1953.)[4]

Before the end of August, four hurricanes had formed in the Atlantic, three of which attained major hurricane status.[3] A major hurricane is a tropical cyclone with winds of at least 111 mph (178 km/h); a storm of this intensity would be classified as a Category 3 or greater on the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Scale introduced in the 1970s.[5] Only five other Atlantic hurricane seasons had three major hurricanes before the end of August. Aside from 1950, this also occurred during the 1886, 1893, 1916, 2004, and 2005 seasons.[6] In contrast to the busy August, only three named storms developed in September—although three of the August hurricanes lasted into September. Hurricane Dog became the strongest hurricane of the season on September 6 with winds of 185 mph (295 km/h); its peak strength occurred over the open Atlantic Ocean, so it did not cause significant damage when it was at its strongest. It was, however, among the severest hurricanes on record in Antigua, where the hurricane struck early in its duration.[3] Six tropical storms or hurricanes formed in October, which at the time was greater than in any other year, and which no other season has broken; this level of October activity been matched only by the 2005 season.[6][nb 2]

In total, there were thirteen tropical storms during the season, of which only two (Tropical Storm How and an unnamed tropical storm) did not attain hurricane status. Overall, there were eight major hurricanes during the year, which is a record that still stands.[6] The Hurricane Hunters made about 300 flights into hurricanes during the season, the most since the practice began in 1943.[3] The number of storms was above average; a typical year experiences eleven tropical storms, six hurricanes, and between two and three major hurricanes.[7] With the numerous major hurricanes, the season produced the second-highest accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) on record, after 2005,[6][8] with a total of 243.[9] This value is an approximation of the combined kinetic energy used by all tropical cyclones throughout the season.[10]

Storms

Hurricane Able

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 12 – August 22 | ||

| Intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min), 953 mbar (hPa) | ||

The beginning of the hurricane season was very inactive, with no tropical cyclones forming during June or July. It was not until the middle of August when a tropical wave spawned the first tropical storm of the year. Tropical Storm Able formed east of the Lesser Antilles on August 12, and strengthened to hurricane status on August 13. Able gradually intensified as it tracked generally west-northwestward, and by early on August 18, Able reached peak winds of 140 mph (220 km/h). Initially, Able was thought to pose a threat to the Bahamas and Florida.[3][6][11] Instead, the hurricane turned to the northwest, and later to the northeast, passing just offshore Cape Hatteras, North Carolina and Cape Cod. Steadily weakening and accelerating as it moved away from the equator, Able struck Nova Scotia as a tropical storm, and later struck Newfoundland as a tropical depression. It dissipated late on August 22 in the far northern Atlantic Ocean.[3][6]

Along the coast of North Carolina, the hurricane produced light winds and rough waves,[12] as well as moderate precipitation. Heavier rainfall occurred in southern New England,[13] causing flooding in portions of New York City and producing slick roads that caused nine traffic fatalities.[14] Able produced hurricane-force winds in Nova Scotia,[3] and damage across Canada totaled over $1 million (1950 CAD, $9.5 million 2012 USD) in the agriculture, communications, and fishing industries.[15] Two people died in Canada when their raft was overturned.[16]

Hurricane Baker

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 20 – September 1 | ||

| Intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min), 979 mbar (hPa) | ||

Tropical Storm Baker developed early on August 20 about 445 mi (720 km) east of Guadeloupe. It quickly attained hurricane status, and by August 21 Baker had intensified to its peak intensity. At this time, the hurricane produced sustained winds of 120 mph (195 km/h) just as it crossed over Antigua,[3][6] where heavy damage was reported. More than 100 homes were damaged or destroyed, which left thousands homeless.[17] Afterward, the hurricane began to weaken, and on August 22 its winds decreased to tropical storm status. The next day it struck southwestern Puerto Rico, and shortly thereafter Baker degenerated into a tropical wave. The remnants of Baker continued west-northwestward, moving through Hispaniola and Cuba.[3][6] In Cuba, 37 people died, and the property losses reached several million dollars.[18]

On August 25, the remnants regenerated into a tropical storm in the western Caribbean Sea. Two days later, Baker entered the Gulf of Mexico, and by the next day Baker had regained hurricane status. It turned northward, reaching a secondary peak intensity of 110 mph (175 km/h) on August 30. Baker weakened slightly before making landfall near Gulf Shores, Alabama with winds of 85 mph (140 km/h) on August 31.[3][6] Property and crop damage totaled $2.55 million (1950 USD, $23.3 million 2012 USD), primarily between Mobile, Alabama and Saint Marks, Florida.[3] Torrential rainfall fell throughout the region, with the largest total occurring in Caryville, Florida, where 15.49 in (393 mm) of precipitation were recorded.[19] The heavy precipitation was responsible for extensive crop damage across the region. The hurricane also spawned two tornadoes, one of which destroyed four houses and a building in Apalachicola, Florida. In Birmingham, Alabama, high wind downed power lines, which caused one death and two injuries due to live wires. While inland, Baker tracked northwestward and eventually dissipated over southeastern Missouri on September 1.[3][6]

Hurricane Charlie

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 21 – September 4 | ||

| Intensity | 115 mph (185 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

Hurricane Charlie developed on August 21 to the southwest of the Cape Verde islands, although this was discovered in subsequent analyses[6]—at the time, the Weather Bureau did not consider Charlie to be a tropical cyclone until almost a week later. For four days, the storm tracked generally to the west as a weak tropical storm. On August 25, it turned to the northwest and intensified, becoming a hurricane on August 28. The next day, after Charlie had turned to the north, reconnaissance flights from the Hurricane Hunters reported peak winds of 115 mph (185 km/h) about 450 mi (740 km) east-southeast of Bermuda.[3]

On August 30, a strengthening high-pressure ridge caused Charlie to execute a small loop over the open Atlantic. The same day, it began weakening, and by September 1, the maximum sustained winds of the storm decreased to 80 mph (130 km/h). The next day, Charlie restrengthened slightly, to 100 mph (160 km/h). On September 2, Charlie turned to the north and northeast. At the time, it co-existed with two other hurricanes, Dog and Easy; it is a rare occurrence for three hurricanes to exist simultaneously in the Atlantic. Charlie slowly weakened and lost tropical characteristics, and by September 5 Charlie had transitioned into an extratropical cyclone about 480 mi (775 km) southeast of Halifax, Nova Scotia. It dissipated later on September 5 without having affected land.[3][6]

Hurricane Dog

| Category 5 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | August 30 – September 12 | ||

| Intensity | 185 mph (295 km/h) (1-min), 948 mbar (hPa) | ||

Hurricane Dog is believed to have developed from a tropical wave that left the coast of Africa on August 24. Its first observation as a tropical cyclone occurred on August 30, when it was a 70 mph (110 km/h) tropical storm. At the time, Dog was located east of the Lesser Antilles, and it quickly attained hurricane status as it moved to the west-northwest. Dog passed just north of the northern Lesser Antilles with winds of 130 mph (210 km/h).[3][6] It was considered among the worst hurricanes in the history of Antigua,[3] where thousands were left homeless.[20] Damage was estimated at $1 million (1950 USD, $9.12 million 2012 USD), and there were two deaths from drowning in the region.[3]

After passing through the Leeward Islands, the hurricane turned to a northerly drift with continued intensification. On September 5, it attained wind speeds that would be equivalent to a Category 5 hurricane on the present-day Saffir-Simpson scale, and the next day Dog reached its peak intensity, with sustained winds of 185 mph (298 km/h). This wind intensity value was estimated by Hurricane Hunters when the hurricane was located about 450 mi (720 km) south-southwest of Bermuda.[3][6]

Maintaining peak intensity for about 18 hours, Dog began a weakening trend as it made a sharp turn to the west. It accelerated to the north on September 10, and two days later Dog passed within 200 mi (320 km) of Cape Cod.[3][6] Newspapers attributed heavy rainfall in the Mid-Atlantic states—which resulted in five deaths—to the hurricane.[21] Further north, the hurricane killed 12 people in New England, and produced a total of $2 million (1950 USD, $18.2 million 2012 USD) of property damage.[3] Twelve others died in two shipwrecks off the coast of Canada.[22] The hurricane later became an extratropical cyclone, passing south of Nova Scotia and eventually losing its identity near Ireland on September 16.[6]

Hurricane Easy

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | September 1 – September 9 | ||

| Intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min), 958 mbar (hPa) | ||

Hurricane Easy developed on September 1 from a trough in the western Caribbean, which persisted after Hurricane Baker moved through the region in late August. Moving northeastward, the hurricane crossed Cuba on September 3 and entered the Gulf of Mexico. Easy turned to the northwest and strengthened to its peak intensity, attaining sustained winds of 125 mph (205 km/h). At the time, Easy was located just off the west coast of Florida; however, a ridge to its north caused the hurricane to stall, execute a small loop, and make landfall near Cedar Key. Following the landfall, Easy moved offshore, turned to the southeast, and made a second landfall west of Tampa on September 6. The hurricane turned northwestward over the Florida Peninsula, and gradually weakened as it moved into Georgia and the southeastern United States. On September 9, Easy dissipated over northeastern Arkansas.[3][6]

Damage in Cuba was minor, although large portions of western Florida experienced hurricane-force winds and heavy rainfall.[3] Yankeetown reported 38.70 in (983 mm) of precipitation in 24 hours, which was, at the time, the largest 24-hour rainfall total on record in the United States.[23] The cumulative total rainfall on Yankeetown from Easy was 45.20 in (1,148 mm), which still retains the record for the wettest tropical cyclone in Florida.[24] Damage was heaviest in Cedar Key, where half of the houses were destroyed and most of the remaining were damaged. The rainfall caused heavy crop damage in the region. Across the state, Easy caused $3 million in damage (1950 USD, $27.4 million 2012 USD); the total was less than expected, due to the sparse population of the affected area. Additionally, the hurricane was indirectly responsible for two deaths due to electrocutions. At the time, Easy was also known as the "Cedar Keys Hurricane".[3]

Hurricane Fox

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | September 8 – September 16 | ||

| Intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

Hurricane Fox was first discovered by Hurricane Hunters on September 10, when it was located about 1,000 mi (1,600 km) east of Puerto Rico. Subsequent analysis indicated that the system formed at least two days earlier. A small system, the hurricane moved generally northwestward and gradually intensified. After turning toward the north, Fox reached its peak intensity with maximum sustained winds of 140 mph (220 km/h) on September 14, as it passed about 300 mi (485 km) east of Bermuda. Following its peak intensity, the hurricane accelerated to the north and northeast. By September 17, Fox had lost all tropical characteristics, and later that day the circulation dissipated about halfway between the Azores and Newfoundland. Fox never affected land along its path. When Fox dissipated, it was the first time in 36 days without an active tropical cyclone in the Atlantic Ocean.[3][6]

Hurricane George

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | September 27 – October 5 | ||

| Intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

George originated from a strong tropical wave when it was located several hundred miles northeast of the Lesser Antilles, and southeast of Bermuda. Forming on September 27, George initially moved toward the north, although it curved westward over the subsequent days. Initially weak, George began strengthening on September 30 as it decreased its forward speed. The next day, while remaining nearly stationary, a nearby ship reported that George had reached hurricane status. It continued moving very slowly, passing only 100 mi (160 km) south of Bermuda.[3][6] The island experienced winds of 30 to 40 mph (40 to 65 km/h).[25] Aside from rainbands, little impact was reported on Bermuda.[26]

The hurricane passed west of Bermuda on October 3, by which time George reached its maximum intensity, attaining sustained winds of 110 mph (175 km/h). It accelerated to the north and later to the northeast, and on October 5 George transitioned into an extratropical cyclone. Shortly thereafter, it passed just south of Newfoundland, and on October 7 the remnants of George dissipated south of Iceland.[3][6]

Tropical Storm How

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | October 1 – October 4 | ||

| Intensity | 60 mph (95 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

A tropical depression formed in the central Gulf of Mexico on October 1, and quickly intensified into Tropical Storm How. Initially, the tropical storm moved west-northwestward and its sustained winds reached a peak strength of 60 mph (95 km/h) by October 2.[3][6] Officials advised small boats to remain at port along the Louisiana coast due to the storm.[27] On October 3, Tropical Storm How turned toward the southwest as it began weakening, and the next day it moved ashore near La Pesca, Tamaulipas as a rapidly weakening tropical cyclone. About six hours after making landfall, How dissipated over the Sierra Madre Oriental in northeastern Mexico. How was the only named storm in the season not to attain hurricane status.[3][6]

Hurricane Item

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | October 8 – October 10 | ||

| Intensity | 110 mph (175 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

On October 8, another tropical storm formed in the Gulf of Mexico just off the northwest coast of the Yucatán Peninsula. Given the name Item, the storm moved westward at first, and attained hurricane status on October 9. Reconnaissance flights by the Hurricane Hunters reported winds of 90 mph (145 km/h); soon after that measurement, Hurricane Item turned to the southwest. On October 10, the hurricane made landfall at peak intensity near Nautla, Veracruz, where sustained winds reached 110 mph (175 km/h). It quickly dissipated over land.[3][6] In the sparsely populated area where Item moved ashore, the hurricane dropped heavy rainfall.[28] Newspaper reports considered it the worst storm to hit Mexico in ten years, with damage in Veracruz totaling around $1.5 million (1950 USD, $13.7 million 2012 USD). The strong winds sank 20 ships, and although there were no reports of casualties, Item caused 15 injuries.[29] Communications were disrupted across the region, and downed trees blocked roads. Near Tuxpam, the winds damaged large areas of banana plantations.[30]

Hurricane Jig

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | October 11 – October 17 | ||

| Intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

A tropical storm was first observed on October 11 in the central Atlantic Ocean, northeast of the Lesser Antilles and southeast of Bermuda. Two days later, a ship reported strong winds and a rapid pressure drop, indicating a hurricane was in the region; the tropical cyclone was given the name Jig. It moved northwestward, steadily intensifying before turning to the north and northeast. On October 15, Hurricane Jig passed about 300 mi (480 km) east of Bermuda, and later that day its sustained winds reached their peak strength of 120 mph (195 km/h). The hurricane began rapidly weakening on October 17. Jig became an extratropical cyclone later that day and quickly dissipated, never having affected land due to its small size.[3][6]

Hurricane King

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | October 13 – October 19 | ||

| Intensity | 120 mph (195 km/h) (1-min), 955 mbar (hPa) | ||

The origins of Hurricane King can be traced to the formation of a tropical storm just off the north coast of Honduras on October 13.[6] Given the name King, the tropical storm was a small weather system throughout its duration. During its first 72 hours as a tropical cyclone, King initially toward the east and east-northeast.[3] On October 16, King's maximum sustained winds reached hurricane strength while the storm was located between Jamaica and the Cayman Islands. The next day, King struck Cuba near Camagüey with winds of 115 mph (185 km/h). King's winds were of sufficient strength to be equivalent to a modern-day Category 3 hurricane; thus, King became the eighth and final major hurricane of the season.[6] The hurricane killed seven people and caused $2 million (1950 USD, $18.2 million 2012 USD) in damage throughout the country.[31]

After reaching the southwestern Atlantic Ocean, King turned northward and later northwestward, striking downtown Miami, Florida on October 18 with winds of 122 mph (197 km/h). It was the most severe hurricane to impact the city since the 1926 Miami hurricane. Across Florida, damage totaled $27.75 million (1950 USD, $253 million 2012 USD), of which $15 million (1950 USD, $137 million 2012 USD) was in the Miami metropolitan area.[3] A preliminary survey indicated there were 12,290 houses damaged in the region, with an additional eight destroyed.[32] Along its path through the state, strong winds were observed around Lake Okeechobee, with a 93 mph (150 km/h) gust in Clewiston. Overall, there were three deaths in the state.[3] Early on October 19, King weakened to tropical storm status over north-central Florida, and later that day it dissipated over western Georgia.[6] There was one additional death in Georgia.[3]

Tropical Storm Twelve

| Tropical storm (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | October 17 – October 24 | ||

| Intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

A tropical storm developed in the east-central Atlantic on October 17. It moved northwestward at first before turning to the northeast on October 19. The storm steadily intensified as it tracked toward the Azores, and it reached a peak intensity of 70 mph (110 km/h) on October 21. Maintaining its peak strength for 30 hours, the storm began a steady weakening trend before crossing through the southern Azores. It turned to the southeast, weakening to tropical depression status on October 24. Subsequently, the system turned to the southwest and quickly dissipated.[6] This tropical storm was not considered to be a tropical storm at the time, and thus the system was not included in the Monthly Weather Review's summary of the 1950 hurricane season.[3] It is unknown when the storm was added to the Atlantic hurricane database,[6] although by 1962, the storm was included in seasonal statistics.[33]

Hurricane Love

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHS) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| Duration | October 18 – October 21 | ||

| Intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min), Unknown | ||

In the wake of Hurricane King moving northward through Florida, an area of low pressure developed into a tropical cyclone on October 18 south of Louisiana. This storm was given the name Love and quickly strengthened, reaching hurricane status shortly thereafter. The storm initially moved westward across the Gulf of Mexico, but soon swung southward into the central portion of the Gulf on October 19. Hurricane Love's maximum sustained winds are believed to have reached a peak intensity of 90 mph (150 km/h). Throughout the hurricane's track, dry air infringed on the western side of the tropical cyclone's circulation, which produced unfavorable conditions for additional tropical cyclogenesis. On October 20, the storm began curving northeastward towards the coast of western Florida; however, the dry air completely circled Love's center of circulation, drastically weakening the cyclone in the process. On October 21, Love weakened to a tropical storm, and it struck the Big Bend region of Florida, north of Cedar Key. At the time, its winds were only of moderate gale force, and the storm dissipated shortly thereafter.[3][6]

Certain areas began preparing for the storm along Florida's west coast. Hospitals set up emergency facilities in case of power failure, and some coastal residents left their homes.[34] Initially, the storm was forecast to strike the Tampa area, but missed to the north as it weakened. It reportedly left little damage in the sparsely populated land where it made landfall.[35]

Storm names

This was the first Atlantic hurricane season in which cyclones that attained at least tropical storm status were given names. The names used to name storms during the 1950 season were taken from the Joint Army/Navy Phonetic Alphabet, which was also used in the 1951 and 1952 hurricane seasons before being replaced by female names in 1953.[4] Names that were not assigned are marked in gray.[36]

|

|

|

See also

- List of Atlantic hurricanes

- List of Atlantic hurricane seasons

- 1950 Pacific hurricane season

- 1950–59 Pacific typhoon seasons

- Pre-1980 North Indian Ocean cyclone seasons

- Pre-1970 Southern Hemisphere tropical cyclone seasons

Notes

- ^ There is an undercount bias of zero to six tropical cyclones per year between 1851 and 1885 and zero to four per year between 1886 and 1910, due to the lack of modern observation techniques, see Tropical cyclone observation. This may have led to significantly lower ACE ratings for hurricane seasons prior to 1910.[1]

- ^ The 2005 Atlantic hurricane season had six fully tropical storms during the month of October; however, the 2005 season also had an unnamed subtropical storm.[6]

References

- ^ Chris Landsea, Hurricane Research Division (2010-05-08). "Subject: E11) How many tropical cyclones have there been each year in the Atlantic basin? What years were the greatest and fewest seen?". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/tcfaq/E11.html. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-06-15). "Hurricane Net is Ready as Season Opens". Sarasota Herald-Tribune. Associated Press. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=G5kcAAAAIBAJ&sjid=wWQEAAAAIBAJ&pg=5928,4688225&dq=hurricane+season&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Grady Norton, U.S. Weather Bureau (1950). "Hurricanes of the 1950 Season". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/general/lib/lib1/nhclib/mwreviews/1950.pdf. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ a b Chris Landsea (2010-03-17). "Subject: B1) How are tropical cyclones named?". Hurricane Research Division. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/tcfaq/B1.html. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ Jack Williams (2005-05-17). "Hurricane scale invented to communicate storm danger". USA Today. http://www.usatoday.com/weather/hurricane/whscale.htm. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae Hurricane Research Division (2009). "Easy-to-Read HURDAT 1851–2009". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/hurdat/easyread-2009.html. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ^ National Hurricane Center (2010). "Tropical Cyclone Climatology". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/pastprofile.shtml. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ Stacy Stewart (2006). "Tropical Storm Zeta Discussion Thirty". National Hurricane Center. http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/archive/2005/dis/al302005.discus.030.shtml?. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ^ Hurricane Research Division (March 2011). "Atlantic basin Comparison of Original and Revised HURDAT". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/hurdat/Comparison_of_Original_and_Revised_HURDAT_mar11.html. Retrieved 2011-07-23.

- ^ Carl Drews (2007-08-24). "Separating the ACE Hurricane Index into Number, Intensity, and Duration". University of Colorado at Boulder. http://acd.ucar.edu/~drews/hurricane/SeparatingTheACE.html. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-08-18). "Hurricane Alerts All of Florida". The Pittsburgh Press. Associated Press. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=uBENAAAAIBAJ&sjid=PWoDAAAAIBAJ&pg=2689,3761537&dq=hurricane&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-08-21). "North Carolina's East Coast Areas Return to Normal". Associated Press.

- ^ David M. Roth (2010). "Rainfall Summary for Hurricane Able (1950)". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/tropical/rain/able1950filledrainblk.gif. Retrieved 2010-04-22.

- ^ Milt Sosin (1950-08-21). "New Caribbean Storm Causes Puerto Rico Alert". Miami Daily News. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=EWE0AAAAIBAJ&sjid=uesFAAAAIBAJ&pg=5376,2441928&dq=hurricane+nova+scotia&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-08-22). "Damage is High". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Associated Press. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=76IpAAAAIBAJ&sjid=4_UDAAAAIBAJ&pg=6841,2659212&dq=hurricane+nova+scotia&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

- ^ "Able – 1950". Environment Canada. 2009. http://www.ec.gc.ca/hurricane/default.asp?lang=En&n=A0AC0965-1. Retrieved 2010-05-23.

- ^ Staff Writer (August 1950). "Storm Wrecks 100 Houses in Antigua". The Daily Gleaner. Trinidad Guardian.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-09-01). "Hurricane Only a "Whisper" Now". The Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=pGsjAAAAIBAJ&sjid=kyMEAAAAIBAJ&pg=5380,253998&dq=hurricane+cuba&hl=en. Retrieved 2011-01-01.

- ^ David M. Roth (2008-10-21). "Rainfall Summary for Hurricane Baker (1950)". Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/tropical/rain/baker1950.html. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-09-02). "Havoc Heaped On Antigua As Storm Strikes Again". The Daily Gleaner. Canadian Press.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-09-12). "Hurricane Misses Nantucket". Lowell Sun.

- ^ "Dog – 1950". Environment Canada. 2009. http://www.ec.gc.ca/hurricane/default.asp?lang=En&n=7E689586-1. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ Bob Swanson & Doyle Rice (2006). "On this date in weather history". USAToday.com. Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. http://web.archive.org/web/20080516214705/http://blogs.usatoday.com/weather/2006/09/on_this_date_in_2.html. Retrieved 2006-09-17.

- ^ David Roth. "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Climatology. Hydrometeorological Prediction Center. http://www.hpc.ncep.noaa.gov/tropical/rain/tcmaxima.html. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-10-04). "Hurricane Nears Bermuda; Winds Rake Texas Coast". Herald-Journal. Associated Press. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=FFgsAAAAIBAJ&sjid=N8sEAAAAIBAJ&pg=3369,3576353&dq=hurricane+bermuda&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-10-05). "Hurricane at Sea off New England". Lewiston Daily Sun. Associated Press. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=k7Q0AAAAIBAJ&sjid=UWgFAAAAIBAJ&pg=5744,370957&dq=hurricane+bermuda&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-05-05.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-10-01). "Miami Bureau Watches Ocean and Gulf Storms". Miami Sunday News. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=GmE0AAAAIBAJ&sjid=u-sFAAAAIBAJ&pg=5444,848190&dq=storm+gulf+mexico&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-10-10). "Mexico's Coast in Storm's Path". St. Petersburg Times. United Press International.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-10-12). "Hurricane Toll High". The Leader-Post. United Press International. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=hehTAAAAIBAJ&sjid=5TgNAAAAIBAJ&pg=4427,1200120&dq=hurricane+worst&hl=en. Retrieved 2011-01-27.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-10-12). "Hurricane Spends Itself In Coastal Mountains". Lewiston Evening Journal. Associated Press. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=r2IpAAAAIBAJ&sjid=LWcFAAAAIBAJ&pg=923,1058771&dq=storm+gulf+mexico&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-05-07.

- ^ "Hurricane Vulnerability in Latin America and The Caribbean: Normalized Damage and Loss Potentials" (PDF). Natural Hazards Review (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration): 101–114. August 2003. doi:10.1061/~ASCE!1527-6988~2003!4:3~101!. http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/hrd/Landsea/NHR-Cuba.pdf.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-10-19). "Reports Show Three Dead, Ten Missing". Reading Eagle. United Press International. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=lMMhAAAAIBAJ&sjid=ep0FAAAAIBAJ&pg=4115,819508&dq=hurricane+florida&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-05-15.

- ^ Cry, G.W.; Haggard, H.W. (August 1962). "North Atlantic Tropical Cyclone Activity: 1900–1961". Monthly Weather Review (American Meteorological Society): 341–349. http://docs.lib.noaa.gov/rescue/mwr/090/mwr-090-08-0341.pdf.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-10-21). "Huffing, Puffing Hurricane Finds the City Ready". St. Petersburg Times. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=ehAmAAAAIBAJ&sjid=TE4DAAAAIBAJ&pg=5929,2257605&dq=hurricane+storm&hl=en. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ^ Staff Writer (1950-10-21). "Florida Hurricane Fizzles, Missing Tampa Bay Area". The Free-Lance Star. http://news.google.com/newspapers?id=2RcQAAAAIBAJ&sjid=U4oDAAAAIBAJ&pg=4475,2102860. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ^ Gary Padgett (2007). "History of the Naming of Atlantic Tropical Cyclones, Part 1 - The Fabulous Fifties". http://www.australiasevereweather.com/cyclones/2008/summ0707.htm. Retrieved 2011-01-13.

External links

|

|||||||||||

|

|

|||||