x86-64

x86-64 is an extension of the x86 instruction set. It supports vastly larger virtual and physical address spaces than are possible on x86, thereby allowing programmers to conveniently work with much larger data sets. x86-64 also provides 64-bit general purpose registers and numerous other enhancements. The original specification was created by AMD, and has been implemented by AMD, Intel, VIA, and others. It is fully backwards compatible with 32-bit code.[1](p13) Because the full 32-bit instruction set remains implemented in hardware without any intervening emulation, existing 32-bit x86 executables run with no compatibility or performance penalties,[2] although existing applications that are recoded to take advantage of new features of the processor design may see significant performance increases.

AMD K8 was the first family of processors implementing the architecture; this was the first significant addition to the x86 architecture designed by a company other than Intel. Intel was forced to follow suit and introduced a modified NetBurst family which was fully software-compatible with AMD's design and specification. VIA Technologies introduced x86-64 in their VIA Isaiah architecture, with the VIA Nano.

AMD later introduced AMD64 as the architecture's marketing name; Intel used the names IA-32e and EM64T before finally settling on the name Intel 64 for their implementation. x86-64 is still used by many in the industry as a vendor-neutral term, as is x64.

The x86-64 specification is distinct from the Intel Itanium (formerly IA-64) architecture, which is not compatible on the native instruction set level with either the x86 or x86-64 architectures.

Contents |

AMD64

The AMD64 instruction set is implemented in AMD's Athlon 64, Athlon 64 FX, Athlon 64 X2, Athlon II, Athlon X2, Opteron, Phenom, Phenom II, Turion 64, Turion 64 X2, and later Sempron processors.

History of AMD64

AMD64 was created as an alternative to Intel and Hewlett Packard's radically different IA-64 architecture. Originally announced in 1999 with a full specification in August 2000,[3] the architecture was positioned by AMD from the beginning as an evolutionary way to add 64-bit computing capabilities to the existing x86 architecture, as opposed to Intel's approach of creating an entirely new 64-bit architecture with IA-64.

The first AMD64-based processor, the Opteron, was released in April 2003.

Architectural features

The primary defining characteristic of AMD64 is the availability of 64-bit general-purpose processor registers, i.e. rax, rbx etc., 64-bit integer arithmetic and logical operations, and 64-bit virtual addresses. The designers took the opportunity to make other improvements as well. The most significant changes include:

- 64-bit integer capability: All general-purpose registers (GPRs) are expanded from 32 bits to 64 bits, and all arithmetic and logical operations, memory-to-register and register-to-memory operations, etc., can now operate directly on 64-bit integers. Pushes and pops on the stack are always in 8-byte strides, and pointers are 8 bytes wide.

- Additional registers: In addition to increasing the size of the general-purpose registers, the number of named general-purpose registers is increased from eight (i.e. eax, ebx, ecx, edx, ebp, esp, esi, edi) in x86 to 16 (i.e. rax, rbx, rcx, rdx, rbp, rsp, rsi, rdi, r8, r9, r10, r11, r12, r13, r14, r15). It is therefore possible to keep more local variables in registers rather than on the stack, and to let registers hold frequently accessed constants; arguments for small and fast subroutines may also be passed in registers to a greater extent. However, AMD64 still has fewer registers than many common RISC ISAs (which typically have 32–64 registers) or VLIW-like machines such as the IA-64 (which has 128 registers); note, however, that because of register renaming the number of physical registers is often much larger than the number of registers exposed by the instruction set.

- Additional XMM (SSE) registers: Similarly, the number of 128-bit XMM registers (used for Streaming SIMD instructions) is also increased from 8 to 16.

- Larger virtual address space: The AMD64 architecture defines a 64-bit virtual address format, of which the low-order 48 bits are used in current implementations.[1](p130) This allows up to 256 TB (248 bytes) of virtual address space. The architecture definition allows this limit to be raised in future implementations to the full 64 bits,[1](p115) extending the virtual address space to 16 EB (264 bytes). This is compared to just 4 GB (232 bytes) for the x86.[4] This means that very large files can be operated on by mapping the entire file into the process' address space (which is often much faster than working with file read/write calls), rather than having to map regions of the file into and out of the address space.

- Larger physical address space: The original implementation of the AMD64 architecture implemented 40-bit physical addresses and so could address up to 1 TB (240 bytes) of RAM.[1](p4) Current implementations of the AMD64 architecture (starting from AMD 10h microarchitecture) extend this to 48-bit physical addresses[5] and therefore can address up to 256 TB of RAM. The architecture permits extending this to 52 bits in the future[1](p24)[6] (limited by the page table entry format);[1](p131) this would allow addressing of up to 4 PB of RAM. For comparison, x86 processors are limited to 64 GB of RAM in Physical Address Extension (PAE) mode,[7] or 4 GB of RAM without PAE mode.[1](p4)

- Larger physical address space in legacy mode: When operating in legacy mode the AMD64 architecture supports Physical Address Extension (PAE) mode, as do most current x86 processors, but AMD64 extends PAE from 36 bits to an architectural limit of 52 bits of physical address. Any implementation therefore allows the same physical address limit as under long mode.[1](p24)

- Instruction pointer relative data access: Instructions can now reference data relative to the instruction pointer (RIP register). This makes position independent code, as is often used in shared libraries and code loaded at run time, more efficient.

- SSE instructions: The original AMD64 architecture adopted Intel's SSE and SSE2 as core instructions. SSE3 instructions were added in April 2005. SSE2 is an alternative to the x87 instruction set's IEEE 80-bit precision with the choice of either IEEE 32-bit or 64-bit floating-point mathematics. This provides floating-point operations compatible with many other modern CPUs. The SSE and SSE2 instructions have also been extended to operate on the eight new XMM registers. SSE and SSE2 are available in 32-bit mode in modern x86 processors; however, if they're used in 32-bit programs, those programs will only work on systems with processors that have the feature. This is not an issue in 64-bit programs, as all AMD64 processors have SSE and SSE2, so using SSE and SSE2 instructions instead of x87 instructions does not reduce the set of machines on which x86-64 programs can be run. SSE and SSE2 are generally faster than, and duplicate most of the features of the traditional x87 instructions, MMX, and 3DNow!.

- No-Execute bit: The "NX" bit (bit 63 of the page table entry) allows the operating system to specify which pages of virtual address space can contain executable code and which cannot. An attempt to execute code from a page tagged "no execute" will result in a memory access violation, similar to an attempt to write to a read-only page. This should make it more difficult for malicious code to take control of the system via "buffer overrun" or "unchecked buffer" attacks. A similar feature has been available on x86 processors since the 80286 as an attribute of segment descriptors; however, this works only on an entire segment at a time. Segmented addressing has long been considered an obsolete mode of operation, and all current PC operating systems in effect bypass it, setting all segments to a base address of 0 and (in their 32 bit implementation) a size of 4 GB. AMD was the first x86-family vendor to implement no-execute in linear addressing mode. The feature is also available in legacy mode on AMD64 processors, and recent Intel x86 processors, when PAE is used.

- Removal of older features: A number of "system programming" features of the x86 architecture are not used in modern operating systems and are not available on AMD64 in long (64-bit and compatibility) mode. These include segmented addressing (although the FS and GS segments are retained in vestigial form for use as extra base pointers to operating system structures)[1](p70), the task state switch mechanism, and Virtual 8086 mode. These features do of course remain fully implemented in "legacy mode," thus permitting these processors to run 32-bit and 16-bit operating systems without modification.

Virtual address space details

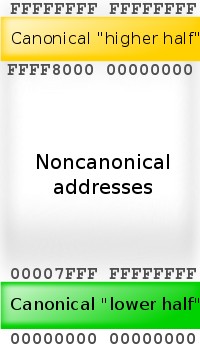

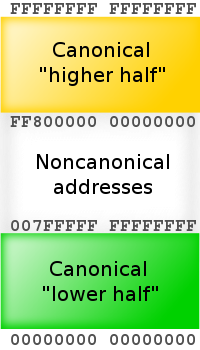

Canonical form addresses

Although virtual addresses are 64 bits wide in 64-bit mode, current implementations (and any chips known to be in the planning stages) do not allow the entire virtual address space of 264 bytes (16 EB) to be used. Most operating systems and applications will not need such a large address space for the foreseeable future (for example, Windows implementations for AMD64 are only populating 16 TB, or 44 bits' worth), so implementing such wide virtual addresses would simply increase the complexity and cost of address translation with no real benefit. AMD therefore decided that, in the first implementations of the architecture, only the least significant 48 bits of a virtual address would actually be used in address translation (page table lookup).[1](p130) Further, bits 48 through 63 of any virtual address must be copies of bit 47 (in a manner akin to sign extension), or the processor will raise an exception. Addresses complying with this rule are referred to as "canonical form."[1](p128) Canonical form addresses run from 0 through 00007FFF`FFFFFFFF, and from FFFF8000`00000000 through FFFFFFFF`FFFFFFFF, for a total of 256 TB of usable virtual address space.

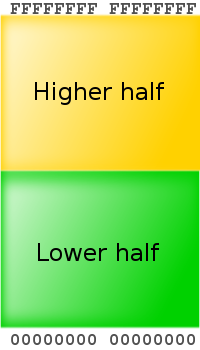

This "quirk" allows an important feature for later scalability to true 64-bit addressing: many operating systems (including, but not limited to, the Windows NT family) take the higher-addressed half of the address space (named kernel space) for themselves and leave the lower-addressed half (user space) for application code, user mode stacks, heaps, and other data regions. The "canonical address" design ensures that every AMD64 compliant implementation has, in effect, two memory halves: the lower half starts at 00000000`00000000 and "grows upwards" as more virtual address bits become available, while the higher half is "docked" to the top of the address space and grows downwards. Also, fixing the contents of the unused address bits prevents their use by operating system as flags, privilege markers, etc., as such use could become problematic when the architecture is extended to 52, 56, 60 and 64 bits.

| Current 48-bit implementation

|

56-bit implementation

|

Full 64-bit implementation

|

Page table structure

The 64-bit addressing mode ("long mode") is a superset of Physical Address Extensions (PAE); because of this, page sizes may be 4 KB (212 bytes) or 2 MB.[1](p118) Long mode also supports page sizes of 1 GB.[1](p118) Rather than the three-level page table system used by systems in PAE mode, systems running in long mode use four levels of page table: PAE's Page-Directory Pointer Table is extended from 4 entries to 512, and an additional Page-Map Level 4 (PML4) Table is added, containing 512 entries in 48-bit implementations.[1](p130) In implementations providing larger virtual addresses, this latter table would either grow to accommodate sufficient entries to describe the entire address range, up to a theoretical maximum of 33,554,432 entries for a 64-bit implementation, or be over ranked by a new mapping level, such as a PML5. A full mapping hierarchy of 4 KB pages for the whole 48-bit space would take a bit more than 512 GB of RAM (about 0.196% of the 256 TB virtual space).

Operating system limits

The operating system can also limit the virtual address space. Details, where applicable, are given in the "Operating system compatibility and characteristics" section.

Physical address space details

Current AMD64 implementations support a physical address space of up to 248 bytes of RAM, or 256 TB,[5]. A larger amount of installed RAM allows the operating system to keep more of the workload's pageable data and code in RAM, which can improve performance,[8] though various workloads will have different points of diminishing returns.[9][10]

The upper limit on RAM that can be used in a given x86-64 system depends on a variety of factors and can be far less than that implemented by the processor. For example, as of June 2010, there are no known motherboards for x86-64 processors that support 256 TB of RAM.[11][12][13][14] The operating system may place additional limits on the amount of RAM that is usable or supported. Details on this point are given in the "Operating system compatibility and characteristics" section of this article.

Operating modes

| Operating mode | Operating system required | Compiled-application rebuild required | Default address size | Default operand size | Register extensions | Typical GPR width | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long mode | 64-bit mode | OS with 64-bit support, or bootloader for 64-bit OS | Yes | 64 | 32 | Yes | 64 |

| Compatibility mode | No | 32 | 32 | No | 32 | ||

| 16 | 16 | 16 | |||||

| Legacy mode | Protected mode | Legacy 16-bit or 32-bit OS; or bootloader for 16, 32, or 64-bit OS | No | 32 | 32 | No | 32 |

| 16 | 16 | 16 | |||||

| Virtual 8086 mode | Legacy 16-bit or 32-bit OS | 16 | 16 | 16 | |||

| Real mode | Legacy 16-bit OS; or bootloader for 16, 32, or 64 bit OS | ||||||

The architecture has two primary modes of operation:

Long mode

The architecture's intended primary mode of operation; it is a combination of the processor's native 64-bit mode and a combined 32-bit and 16-bit compatibility mode. It is used by 64-bit operating systems. Under a 64-bit operating system, 64-bit programs run under 64-bit mode, and 32-bit and 16-bit protected mode applications (that do not need to use either real mode or virtual 8086 mode in order to execute at any time) run under compatibility mode. Real-mode programs and programs that use virtual 8086 mode at any time cannot be run in long mode unless they are emulated.

Since the basic instruction set is the same, there is almost no performance penalty for executing protected mode x86 code. This is unlike Intel's IA-64, where differences in the underlying ISA means that running 32-bit code must be done either in emulation of x86 (making the process slower) or with a dedicated x86 core. However, on the x86-64 platform, many x86 applications could benefit from a 64-bit recompile, due to the additional registers in 64-bit code and guaranteed SSE2-based FPU support, which a compiler can use for optimization. However, applications that regularly handle integers wider than 32 bits, such as cryptographic algorithms, will need a rewrite of the code handling the huge integers in order to take advantage of the 64-bit registers.

Legacy mode

The mode used by 16-bit (protected mode or real mode) and 32-bit operating systems. In this mode, the processor acts just like an x86 processor, and only 16-bit or 32-bit code can be executed. Legacy mode allows for a maximum of 32 bit virtual addressing which limits the virtual address space to 4 GB.[1](p14)(p24)(p118) 64-bit programs cannot be run from legacy mode.

AMD64 implementations

The following processors implement the AMD64 architecture:

- AMD Athlon 64

- AMD Athlon 64 X2

- AMD Athlon 64 FX

- AMD Athlon II (followed by 'X2', 'X3', or 'X4' to indicate the number of cores, and XLT models)

- AMD Opteron

- AMD Turion 64

- AMD Turion 64 X2

- AMD Sempron ("Palermo" E6 stepping and all "Manila" models)

- AMD Phenom (followed by 'X3' or 'X4' to indicate the number of cores)

- AMD Phenom II (followed by 'X2', 'X3', 'X4' or 'X6' to indicate the number of cores)

Intel 64

Intel 64 is Intel's implementation of x86-64. It is used in newer versions of Pentium 4, Celeron D, Xeon and Pentium Dual-Core processors, the Atom 230, 330, D510, and N450 and in all versions of the Pentium D, Pentium Extreme Edition, Core 2, Core i7, Core i5 and Core i3 processors.

History of Intel 64

Historically, AMD has developed and produced processors patterned after Intel's original designs, but with x86-64, roles were reversed: Intel found itself in the position of adopting the architecture which AMD had created as an extension to Intel's own x86 processor line.

Intel's project was originally codenamed Yamhill (after the Yamhill River in Oregon's Willamette Valley). After several years of denying its existence, Intel announced at the February 2004 IDF that the project was indeed underway. Intel's chairman at the time, Craig Barrett, admitted that this was one of their worst kept secrets.[15][16]

Intel's name for this technology has changed several times. The name used at the IDF was CT (presumably for Clackamas Technology, another codename from an Oregon river); within weeks they began referring to it as IA-32e (for IA-32 extensions) and in March 2004 unveiled the "official" name EM64T (Extended Memory 64 Technology). In late 2006 Intel began instead using the name Intel 64 for its implementation, paralleling AMD's use of the name AMD64.[17]

Intel 64 implementations

Intel's first processor to activate the Intel 64 technology was the multi-socket processor Xeon code-named Nocona later in 2004. In contrast, the initial Prescott chips (February 2004) did not enable this feature. Intel subsequently began selling Intel 64-enabled Pentium 4s using the E0 revision of the Prescott core, being sold on the OEM market as the Pentium 4, model F. The E0 revision also adds eXecute Disable (XD) (Intel's name for the NX bit) to Intel 64, and has been included in then current Xeon code-named Irwindale. Intel's official launch of Intel 64 (under the name EM64T at that time) in mainstream desktop processors was the N0 Stepping Prescott-2M. All 9xx, 8xx, 6xx, 5x9, 5x6, 5x1, 3x6, and 3x1 series CPUs have Intel 64 enabled, as do the Core 2 CPUs, as will future Intel CPUs for workstations or servers. Intel 64 is also present in the last members of the Celeron D line.

The first Intel mobile processor implementing Intel 64 is the Merom version of the Core 2 processor, which was released on 27 July 2006. None of Intel's earlier notebook CPUs (Core Duo, Pentium M, Celeron M, Mobile Pentium 4) implements Intel 64.

The following processors implement the Intel 64 architecture:

- Intel NetBurst microarchitecture

- Intel Core microarchitecture

- Intel Xeon (all models since "Woodcrest")

- Intel Core 2 (Including Mobile processors since "Merom")

- Intel Pentium Dual-Core (E2140, E2160, E2180, E2200, E2220, E5200, E5300, E5400, E6300, E6500, T2310, T2330, T2370, T2390, T3200 and T3400)

- Intel Celeron (Celeron 4x0; Celeron M 5xx; E3200, E3300, E3400)

- Intel Atom microarchitecture

- Intel Nehalem-Westmere microarchitecture

VIA's x86-64 implementation

- VIA Technologies Isaiah microarchitecture, implemented in the VIA Nano

Differences between AMD64 and Intel 64

There are a few differences between the two instruction sets. Compilers generally produce binaries that are compatible with both (that is, compatible with the subset of x86-64 that is common to both AMD64 and Intel 64), making these differences mainly of interest to developers of compilers and operating systems.

Recent implementations

- Intel 64's BSF and BSR instructions act differently when the source is 0 and the operand size is 32 bits. The processor sets the zero flag and leaves the upper 32 bits of the destination undefined.

- AMD64 requires a different microcode update format and control MSRs while Intel 64 implements microcode update unchanged from their 32-bit only processors.

- Intel 64 lacks some model-specific registers that are considered architectural to AMD64. These include SYSCFG, TOP_MEM, and TOP_MEM2.

- Intel 64 allows SYSCALL and SYSRET only in long mode (not in compatibility mode). It allows SYSENTER and SYSEXIT in both modes.

- AMD64 lacks SYSENTER and SYSEXIT in both sub-modes of long mode.

- Near branches with the 66H (operand size) prefix behave differently. Intel 64 clears only the top 32 bits, while AMD64 clears the top 48 bits.

Older implementations

- Early AMD64 processors lacked the CMPXCHG16B instruction, which is an extension of the CMPXCHG8B instruction present on most post-486 processors. Similar to CMPXCHG8B, CMPXCHG16B allows for atomic operations on 128-bit double quadword (or oword) data types. This is useful for parallel algorithms that use compare and swap on data larger than the size of a pointer, common in lock-free and wait-free algorithms. Without CMPXCHG16B one must use workarounds, such as a critical section or alternative lock-free approaches.[1]

- Early AMD and Intel 64-bit CPUs lacked LAHF and SAHF instructions. AMD introduced the instructions with their Athlon 64, Opteron and Turion 64 revision D processors in March 2005[18][19][20] while Intel introduced the instructions with the Pentium 4 G1 step in December 2005. LAHF and SAHF are load and store instructions, respectively, for certain status flags. These instructions are used for virtualization and floating-point condition handling.

- Early Intel CPUs with Intel 64 also lack the NX bit (No Execute bit) of the AMD64 architecture. The NX bit marks memory pages as non-executable, allowing protection against many types of malicious code.

- Early Intel 64 implementations only allowed access to 64 GB of physical memory while original AMD64 implementations, of that time, allowed access to 1 TB of physical memory. Recent AMD64 and Intel 64 implementations now provide 256 TB of physical address space (and AMD plans an expansion to 4 PB). Physical memory capacities of this size are appropriate for large-scale applications (such as large databases), and high-performance computing (centrally oriented applications, web-based applications and scientific computing).

- AMD64 originally lacked the MONITOR and MWAIT instructions, used by operating systems to better deal with Intel's Hyper-threading feature, later for dual core thread management, and also to enter specific low power states.

- Intel 64 lacked the ability to save and restore a reduced (and thus faster) version of the floating-point state (involving the FXSAVE and FXRSTOR instructions).

Operating system compatibility and characteristics

The following operating systems and releases support the x86-64 architecture in long mode.

BSD

DragonFly BSD

Preliminary infrastructure work was started in February 2004 for a x86-64 port.[21] This development later stalled. Development started again during July 2007 [22] and continued during Google Summer of Code 2008 and SoC 2009.[23][24] The first official release to contain x86-64 support was version 2.4.[25]

FreeBSD

FreeBSD first added x86-64 support under the name "amd64" as an experimental architecture in 5.1-RELEASE in June 2003. It was included as a standard distribution architecture as of 5.2-RELEASE in January 2004. Since then, FreeBSD has designated it as a Tier 1 platform. The 6.0-RELEASE version cleaned up some quirks with running x86 executables under amd64, and most drivers work just as they do on the x86 architecture. Work is currently being done to integrate more fully the x86 application binary interface (ABI), in the same manner as the Linux 32-bit ABI compatibility currently works.

NetBSD

x86-64 architecture support was first committed to the NetBSD source tree on 19 June 2001. As of NetBSD 2.0, released on 9 December 2004, NetBSD/amd64 is a fully integrated and supported port.

OpenBSD

OpenBSD has supported AMD64 since OpenBSD 3.5, released on 1 May 2004. Complete in-tree implementation of AMD64 support was achieved prior to the hardware's initial release due to AMD's loaning of several machines for the project's hackathon that year. OpenBSD developers have taken to the platform because of its support for the NX bit, which allowed for an easy implementation of the W^X feature.

The code for the AMD64 port of OpenBSD also runs on Intel 64 processors which contains cloned use of the AMD64 extensions, but since Intel left out the page table NX bit in early Intel 64 processors, there is no W^X capability on those Intel CPUs; later Intel 64 processors added the NX bit under the name "XD bit". Symmetric multiprocessing (SMP) works on OpenBSD's AMD64 port, starting with release 3.6 on 1 November 2004.

DOS

It is possible to enter long mode under DOS without a DOS extender[26], but the user must return to real mode in order to call BIOS or DOS interrupts.

It may also be possible to enter long mode with a DOS extender similar to DOS/4GW, but more complex since x86-64 lacks virtual 8086 mode. DOS itself is not aware of that, and no benefits should be expected unless running DOS in an emulation with an adequate virtualization driver backend, for example: the mass storage interface.

Linux

Linux was the first operating system kernel to run the x86-64 architecture in long mode, starting with the 2.4 version in 2001 (prior to the physical hardware's availability).[27][28] Linux also provides backward compatibility for running 32-bit executables. This permits programs to be recompiled into long mode while retaining the use of 32-bit programs. Several Linux distributions currently ship with x86-64-native kernels and userlands. Some, such as SUSE, Mandriva and Debian GNU/Linux, allow users to install a set of 32-bit components and libraries when installing off a 64-bit DVD, thus allowing most existing 32-bit applications to run alongside the 64-bit OS. Other distributions, such as Fedora, Ubuntu, and Arch Linux, are available in one version compiled for a 32-bit architecture and another compiled for a 64-bit architecture.

There is an attempt to run kernel in compatibility mode and to be able to run 64 bit applications in a 32 bit kernel; the name of this project is LINUX PAE64.[2]

64-bit Linux allows up to 128 TB of address space for individual processes, and can address approximately 64 TB of physical memory, subject to processor and system limitations.

Mac OS X

Mac OS X v10.6 is the first version of Mac OS X that supports a 64-bit kernel. However, with its first release (v10.6.0), not all 64-bit computers are currently supported. The 64-bit kernel, like the 32-bit kernel, supports 32-bit applications; both kernels also support 64-bit applications. 32-bit applications have a virtual address space limit of 4 GB under either kernel.[29][30]

The 64-bit kernel does not support 32-bit kernel extensions, and the 32-bit kernel does not support 64-bit kernel extensions.

Mac OS X v10.5 supports 64-bit GUI applications using Cocoa, Quartz, OpenGL and X11 on 64-bit Intel-based machines, as well as on 64-bit PowerPC machines.[31] All non-GUI libraries and frameworks also support 64-bit applications on those platforms. The kernel, and all kernel extensions, are 32-bit only.

Mac OS X v10.4.7 and higher versions of Mac OS X v10.4 run 64-bit command-line tools using the POSIX and math libraries on 64-bit Intel-based machines, just as all versions of Mac OS X v10.4 and higher run them on 64-bit PowerPC machines. No other libraries or frameworks work with 64-bit applications in Mac OS X v10.4.[32] The kernel, and all kernel extensions, are 32-bit only.

Mac OS X uses the universal binary format to package 32- and 64-bit versions of application and library code into a single file; the most appropriate version is automatically selected at load time. In Mac OS X 10.6, the universal binary format is also used for the kernel and for those kernel extensions that support both 32-bit and 64-bit kernels.

Solaris

Solaris 10 and later releases support the x86-64 architecture. Just as with the SPARC architecture, there is only one operating system image for all 32-bit and 64-bit x86 systems; this is labeled as the "x64/x86" DVD-ROM image.

Default behavior is to boot a 64-bit kernel, allowing both 64-bit and existing or new 32-bit executables to be run. A 32-bit kernel can also be manually selected, in which case only 32-bit executables will run. The isainfo command can be used to determine if a system is running a 64-bit kernel.

Windows

x86-64 editions of Microsoft Windows client and server, Windows XP Professional x64 Edition and Windows Server 2003 x64 Edition were released in March 2005. Internally they are actually the same build (5.2.3790.1830 SP1), as they share the same source base and operating system binaries, so even system updates are released in unified packages, much in the manner as Windows 2000 Professional and Server editions for x86. Windows Vista, which also has many different editions, was released in January 2007. Windows for x86-64 has the following characteristics:

- 8 TB of "user mode" virtual address space per process. A 64-bit program can use all of this, subject of course to backing store limits on the system, and provided it is linked with the "large address aware" option.[33] This is a 4096-fold increase over the default 2 GB user-mode virtual address space offered by 32-bit Windows.[34][35]

- 8 TB of kernel mode virtual address space for the operating system.[34] As with the user mode address space,, this is a 4096-fold increase over 32-bit Windows versions. The increased space is primarily of benefit to the file system cache and kernel mode "heaps" (non-paged pool and paged pool). Windows only uses a total of 16 TB out of the 256 TB implemented by the processors because early AMD64 processors lacked a CMPXCHG16B instruction.[36]

- Ability to run existing 32-bit applications (.exe's) and dynamic link libraries (.dll's). Furthermore, a 32-bit program, if it was linked with the "large address aware" option,[33] can use up to 4 GB of virtual address space in 64-bit Windows, instead of the default 2 GB (optional 3 GB with /3GB boot option and "large address aware" link option) offered by 32-bit Windows.[37] Unlike the use of the /3GB boot option on x86, this does not reduce the kernel mode virtual address space available to the operating system. 32-bit applications can therefore benefit from running on x64 Windows even if they are not recompiled for the x64 processor.

- Both 32- and 64-bit applications, if not linked with "large address aware," are limited to 2 GB of virtual address space.

- Ability to use up to 128 GB (Windows XP/Vista), 192 GB (Windows 7), 1 TB (Windows Server 2003), or 2 TB (Windows Server 2008) of random access memory (RAM).

- LLP64 data model: "int" and "long" types are 32 bits wide, long long is 64 bits, while pointers and types derived from pointers are 64 bits wide.

- Kernel mode device drivers must be 64-bit versions; there is no way to run 32-bit kernel-mode executables within the 64-bit operating system. User mode device drivers can be either 32-bit or 64-bit.

- 16-bit Windows (Win16) and DOS applications will not run on x86-64 versions of Windows due to removal of virtual DOS machine subsystem (NTVDM).

- Full implementation of the NX (No Execute) page protection feature. This is also implemented on recent 32-bit versions of Windows when they are started in PAE mode.

- Instead of FS segment descriptor on x86 versions of the Windows NT family, GS segment descriptor is used to point to two operating system defined structures: Thread Information Block (NT_TIB) in user mode and Processor Control Region (KPCR) in kernel mode. Thus, for example, in user mode GS:0 is the address of the first member of the Thread Information Block. Maintaining this convention made the x86-64 port easier, but required AMD to retain the function of the FS and GS segments in long mode — even though segmented addressing per se is not really used by any modern operating system.[38]

- Early reports claimed that the operating system scheduler would not save and restore the x87 FPU machine state across thread context switches. Observed behavior shows that this is not the case: the x87 state is saved and restored, except for kernel-mode-only threads (a limitation that exists in the 32-bit version as well). The most recent documentation available from Microsoft states that the x87/MMX/3DNow! instructions may be used in long mode, but that they are deprecated and may cause compatibility problems in the future.[37]

- Some components like Microsoft Jet Database Engine and Data Access Objects will not be ported to 64-bit architectures such as x86-64 and IA-64.[39][40]

- Microsoft Visual Studio can compile native applications to target only the x86-64 architecture, that will run only on 64-bit Microsoft Windows, or the x86 architecture which will run as a 32-bit application on 32-bit Microsoft Windows or 64-bit Microsoft Windows in WoW64 emulation mode. Managed applications can be compiled either in x86, x86-64 or AnyCPU modes. While the first two modes behave like their x86 or x86-64 native code counterparts respectively, when using the AnyCPU mode, the applications runs as a 32-bit application in 32-bit Microsoft Windows or as a 64-bit application in 64-bit Microsoft Windows.

Industry naming conventions

Since AMD64 and Intel 64 are substantially similar, many software and hardware products use one vendor-neutral term to indicate their compatibility with both implementations. AMD's original designation for this processor architecture, "x86-64", is still sometimes used for this purpose, as is the variant "x86_64".[41] Other companies, such as Microsoft and Sun Microsystems, use the contraction "x64" in marketing material.

The term IA-64 refers to the Itanium processor, and should not be confused with x86-64, as it is a completely different instruction set.

Many operating systems and products, especially those that introduced x86-64 support prior to Intel's entry into the market, use the term "AMD64" or "amd64" to refer to both AMD64 and Intel 64.

- BSD systems such as FreeBSD, MidnightBSD, NetBSD and OpenBSD refer to both AMD64 and Intel 64 under the architecture name "amd64".

- The Linux kernel refers to 64-bit architecture as "x86_64".

- The GNU Compiler Collection refers to 64-bit architecture as "amd64".

- Haiku: refers to 64-bit architecture as "x86_64".

- Java Development Kit (JDK): The name "amd64" is used in directory names containing x86-64 files.

- Mac OS X: Apple refers to 64-bit architecture as "x86_64", as noted with the Terminal command

archand in their developer documentation. [3]

- Microsoft Windows: x86-64 versions of Windows use the AMD64 moniker internally to designate various components which use or are compatible with this architecture. For example, the system folder on a Windows x86-64 Edition installation CD-ROM is named "AMD64", in contrast to "i386" in 32-bit versions.

- Solaris: The "isalist" command in Sun's Solaris operating system identifies both AMD64- and Intel 64–based systems as "amd64".

- T2 SDE refer to both AMD64 and Intel 64 under the architecture name "x86-64", in source code directories and package meta information.

Legal issues

AMD licensed its x86-64 design to Intel, where it is marketed under the name Intel 64 (formerly EM64T). AMD's design replaced earlier attempts by Intel to design its own x86-64 extensions which had been referred to as IA-32e. As Intel licenses AMD the right to use the original x86 architecture (upon which AMD's x86-64 is based), these rival companies now rely on each other for 64-bit processor development. This has led to a case of mutually assured destruction should either company refuse to renew the license.[42] Should such a scenario take place, AMD would no longer be authorized to produce any x86 processors, and Intel would no longer be authorized to produce x86-64 processors, forcing it back to the x86 architecture. However, the agreement[43] provides that if one party breaches the agreement it loses all rights to the other party's technology while the other party receives perpetual rights to all licensed technology. In 2009, AMD and Intel settled several lawsuits and cross-licensing disagreements, extending their cross-licensing agreements for the foreseeable future and settling several anti-trust complaints.[44]

See also

- NX bit

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 AMD Corporation (September 2007). "Volume 2: System Programming" (pdf). AMD64 Architecture Programmer's Manual. AMD Corporation. http://support.amd.com/us/Processor_TechDocs/24593.pdf. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ↑ IBM Corporation (2007-09-06). "IBM WebSphere Application Server 64-bit Performance Demystified". p. 14. ftp://ftp.software.ibm.com/software/webserver/appserv/was/64bitPerf.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-09. ""Figures 5, 6 and 7 also show the 32-bit version of WAS runs applications at full native hardware performance on the POWER and x86-64 platforms. Unlike some 64-bit processor architectures, the POWER and x86-64 hardware does not emulate 32-bit mode. Therefore applications that do not benefit from 64-bit features can run with full performance on the 32-bit version of WebSphere running on the above mentioned 64-bit platforms.""

- ↑ AMD (August 10, 2000). "AMD Releases x86-64 Architectural Specification; Enables Market Driven Migration to 64-Bit Computing". Press release. http://www.amd.com/us-en/Corporate/VirtualPressRoom/0,,51_104_543_552~715,00.html. Retrieved 2007-08-03.

- ↑ "Intel® 64 and IA-32 Architectures Software Developer’s Manual, Volume 3A: System Programming Guide, Part 1" (pdf). pp. 4–10. http://www.intel.com/Assets/PDF/manual/253668.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-29.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "BIOS and Kernel Developer’s Guide (BKDG) For AMD Family 10h Processors" (pdf). p. 24. http://www.amd.com/us-en/assets/content_type/white_papers_and_tech_docs/31116-Public-GH-BKDG_3.20_2-4-09.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-29. "Physical address space increased to 48 bits."

- ↑ "Myth and facts about 64-bit Linux®" (pdf). 2008-03-02. p. 7. http://www.amd64.org/fileadmin/user_upload/pub/64bit_Linux-Myths_and_Facts.pdf. Retrieved 2010-05-30. "Physical address space increased to 48 bits"

- ↑ Shanley, Tom (1998). Pentium Pro and Pentium II System Architecture. PC System Architecture Series (Second ed.). Addison-Wesley. p. 445. ISBN 0-201-30973-4.

- ↑ Jeff Tyson (2004-01-15). "How Virtual Memory Works". howstuffworks. http://computer.howstuffworks.com/virtual-memory.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-07. "The read/write speed of a hard drive is much slower than RAM, and the technology of a hard drive is not geared toward accessing small pieces of data at a time. If your system has to rely too heavily on virtual memory, you will notice a significant performance drop. The key is to have enough RAM to handle everything you tend to work on simultaneously."

- ↑ Jason Dunn (2003-09-03). "Computer RAM: A Crucial Component in Video Editing". Microsoft Corporation. http://www.microsoft.com/windowsxp/using/moviemaker/expert/dunn_03august11_ram.mspx. Retrieved 2010-06-09. "There's a point of diminishing returns where adding more RAM won't give you better system performance."

- ↑ "Understanding Memory Configurations and Exchange Performance". Microsoft Corporation. 2003-09-03. http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/dd346700.aspx. Retrieved 2010. "There is, however, a point of diminishing returns at which adding memory to the server may not be justifiable based on price and performance."

- ↑ "Opteron 6100 Series Motherboards". Supermicro Corporation. http://www.supermicro.com/Aplus/motherboard/Opteron6100/. Retrieved 2010-06-22.

- ↑ "Supermicro XeonSolutions". Supermicro Corporation. http://www.supermicro.com/products/motherboard/Xeon1333/#1366. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ "Opteron 8000 Series Motherboards". Supermicro Corporation. http://www.supermicro.com/Aplus/motherboard/Opteron8000/. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ "Tyan Product Matrix". MiTEC International Corporation. http://www.supermicro.com/products/motherboard/Core/index.cfm#1366. Retrieved 2010-06-21.

- ↑ "Craig Barrett confirms 64 bit address extensions for Xeon. And Prescott", from The Inquirer

- ↑ "A Roundup of 64-Bit Computing", from internetnews.com

- ↑ "Intel 64 Architecture". Intel. http://www.intel.com/technology/intel64/index.htm. Retrieved 2007-06-29.

- ↑ "Revision Guide for AMD Athlon 64 and AMD Opteron Processors", from AMD

- ↑ "AMD Turion 64 pictured up and running", from The Inquirer

- ↑ "Athlon 64 revision E won't work on some Nforce 3/4 boards", from The Inquirer

- ↑ "cvs commit: src/sys/amd64/amd64 genassym.c src/sys/amd64/include asm.h atomic.h bootinfo.h coredump.h cpufunc.h elf.h endian.h exec.h float.h fpu.h frame.h globaldata.h ieeefp.h limits.h lock.h md_var.h param.h pcb.h pcb_ext.h pmap.h proc.h profile.h psl.h ...". http://leaf.dragonflybsd.org/mailarchive/commits/2004-02/msg00011.html. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ "AMD64 port". http://leaf.dragonflybsd.org/mailarchive/users/2007-07/msg00016.html. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ "DragonFlyBSD: GoogleSoC2008". http://www.dragonflybsd.org/docs/developer/GoogleSoC2008/. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ "Summer of Code accepted students". http://leaf.dragonflybsd.org/mailarchive/users/2009-04/msg00091.html. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ "DragonFlyBSD: release24". http://www.dragonflybsd.org/release24/. Retrieved 2009-05-03.

- ↑ Tutorial for entering protected and long mode from DOS

- ↑ Andi Kleen (2001-06-26). "Porting Linux to x86-64". http://www.x86-64.org/pipermail/announce/2001-June/000020.html. "Status: The kernel, compiler, tool chain work. The kernel boots and work on simulator and is used for porting of userland and running programs"

- ↑ Andi Kleen. "Andi Kleen's Page". http://www.halobates.de/. "This was the original paper describing the Linux x86-64 kernel port back when x86-64 was only available on simulators."

- ↑ John Siracusa. "Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard: the Ars Technica review". Ars Technica LLC. http://arstechnica.com/apple/reviews/2009/08/mac-os-x-10-6.ars/5. Retrieved 2010-06-20.

- ↑ "Mac OS X Technology". Apple. http://www.apple.com/macosx/technology/. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ↑ Apple - Mac OS X Leopard - Technology - 64 bit

- ↑ Apple - Mac OS X Xcode 2.4 Release Notes: Compiler Tools

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 "/LARGEADDRESSAWARE (Handle Large Addresses)". Visual Studio 2005 Documentation - Visual C++ - Linker Options. Microsoft. http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/wz223b1z(VS.80).aspx. Retrieved 2010-06-19. "The /LARGEADDRESSAWARE option tells the linker that the application can handle addresses larger than 2 gigabytes."

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Matt Pietrek (2006-05). "Everything You Need To Know To Start Programming 64-Bit Windows Systems". Microsoft. http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/magazine/cc300794.aspx. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ↑ Chris St. Amand (2006-01). "Making the Move to x64". Microsoft. http://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/magazine/2006.01.insidemscom.aspx. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ↑ "Behind Windows x86-64’s 44-bit Virtual Memory Addressing Limit". http://www.alex-ionescu.com/?p=50. Retrieved 2009-07-02.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 "64-bit programming for Game Developers". http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/library/ee418798(VS.85).aspx#Porting_to_64bit.

- ↑ "Everything You Need To Know To Start Programming 64-Bit Windows Systems". http://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/magazine/cc300794.aspx. "On x86-64 versions of Windows, the FS register has been replaced by the GS register."

- ↑ Microsoft Developer Network - General Porting Guidelines (64-bit Windows Programming)

- ↑ Microsoft Developer Network - Data Access Road Map

- ↑ Kevin Van Vechten (August 9, 2006). "re: Intel XNU bug report". Darwin-dev mailing list. Apple Computer. http://lists.apple.com/archives/Darwin-dev/2006/Aug/msg00095.html. Retrieved 2006-10-05. "The kernel and developer tools have standardized on "x86_64" for the name of the Mach-O architecture"

- ↑ "AMD plays antitrust poker for Intel's X86 licence". Incisive Media Limited. 2009-02-03. http://www.theinquirer.net/inquirer/opinion/759/1050759/amd-plays-antitrust-poker-intel-x86-licence. Retrieved 2009-02-26.

- ↑ "Patent Cross License Agreement Between AMD and Intel". 2001-01-01. http://contracts.corporate.findlaw.com/agreements/amd/intel.license.2001.01.01.html. Retrieved 2009-08-23.

- ↑ "AMD Intel Settlement Agreement". http://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/2488/000119312509236705/dex101.htm.

External links

- AMD's free technical documentation for the AMD64 architecture

- AMD's AMD64 documentation on CD-ROM (U.S. and Canada only) and downloadable PDF format

- AMD64 Technology: Overview of the AMD64 Architecture (PDF)

- x86-64: Extending the x86 architecture to 64-bits - technical talk by the architect of AMD64 (video archive), and second talk by the same speaker (video archive)

- AMD's "Enhanced Virus Protection"

- Intel tweaks EM64T for full AMD64 compatibility

- Analyst: Intel Reverse-Engineered AMD64

- Early report of differences between Intel IA32e and AMD64

- Porting to 64-bit GNU/Linux Systems, by Andreas Jaeger from GCC Summit 2003 [4]. An excellent paper explaining almost all practical aspects for a transition from 32-bit to 64-bit.

- Tech Report article: 64-bit computing in theory and practice

- Intel 64 Architecture

- Intel® Software Network, 64 bits"

- TurboIRC.COM tutorial of entering the protected and the long mode the raw way from DOS

- Optimization of 64-bit programs

- Seven Steps of Migrating a Program to a 64-bit System

- Memory Limits for Windows Releases

- Intel® Software Network, Forum "64-Bit Programming"