Linezolid

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

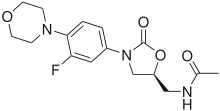

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| (S)-N-({3-[3-fluoro-4-(morpholin-4-yl)phenyl]-2-oxo-1,3-oxazolidin-5-yl}methyl)acetamide | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 165800-03-3 |

| ATC code | J01XX08 |

| PubChem | CID 441401 |

| DrugBank | APRD01073 |

| ChemSpider | 390139 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C16H20FN3O4 |

| Mol. mass | 337.346 g/mol |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | ~100% (oral) |

| Protein binding | Low (31%) |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (50–70%, CYP not involved) |

| Half-life | 4.2–5.4 hours (shorter in children) |

| Excretion | Nonrenal, renal, and fecal |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Licence data | US FDA:link |

| Pregnancy cat. | C (Au), C (U.S.) |

| Legal status | S4 (Au), POM (UK), ℞-only (U.S.) |

| Routes | Intravenous infusion, oral |

| |

|

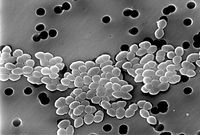

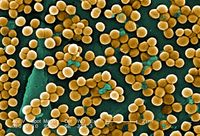

Linezolid (INN) (pronounced /lɪˈnɛzəlɪd/, li-NE-zə-lid) is a synthetic antibiotic used for the treatment of serious infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria that are resistant to several other antibiotics. A member of the oxazolidinone class of drugs, linezolid is active against most Gram-positive bacteria that cause disease, including streptococci, vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).[1] The main indications of linezolid are infections of the skin and soft tissues and pneumonia (particularly hospital-acquired pneumonia), although off-label use for a variety of other infections is becoming popular. Linezolid is marketed by Pfizer under the trade names Zyvox (in the United States, United Kingdom, Australia, and several other countries), Zyvoxid (in Europe), and Zyvoxam (in Canada and Mexico). Generics are also available in India, such as Linospan (Cipla).

Discovered in the 1990s and first approved for use in 2000, linezolid was the first commercially available oxazolidinone antibiotic. As of 2009, it is the only marketed oxazolidinone, although others are in development. As a protein synthesis inhibitor, it stops the growth of bacteria by disrupting their production of proteins. Although many antibiotics work this way, the exact mechanism of action of linezolid appears to be unique to the oxazolidinone class. Bacterial resistance to linezolid has remained very low since it was first detected in 1999, although it may be increasing.

When administered for short periods, linezolid is a relatively safe drug; it can be used in patients of all ages and in people with liver disease or poor kidney function. Common adverse effects of short-term use include headache, diarrhea, and nausea. Long-term use, however, has been associated with serious adverse effects; linezolid can cause bone marrow suppression and low platelet counts, particularly when used for more than two weeks. If used for longer periods still, it may cause peripheral neuropathy (which can be irreversible), optic nerve damage, and lactic acidosis (a buildup of lactic acid in the body), all most likely due to mitochondrial toxicity.

Linezolid is quite expensive, as a course of treatment can cost up to several thousand U.S. dollars;[2] nonetheless, it appears to be more cost-effective than comparable antibiotics,[3] mostly because of the possibility of switching from intravenous to oral administration as soon as patients are stable enough, without the need for dose adjustments.

Contents |

History

The oxazolidinones have been known as monoamine oxidase inhibitors since the late 1950s. Their antimicrobial properties were discovered by researchers at E.I. duPont de Nemours in the 1970s.[4] In 1978, DuPont patented a series of oxazolidinone derivatives as being effective in the treatment of bacterial and fungal plant diseases, and in 1984, another patent described their usefulness in treating bacterial infections in mammals.[4][5] In 1987, DuPont scientists presented a detailed description of the oxazolidinones as a new class of antibiotics with a novel mechanism of action.[4][6] Early compounds were found to produce liver toxicity, however, and development was discontinued.[7]

Pharmacia & Upjohn (now part of Pfizer) started its own oxazolidinone research program in the 1990s. Studies of the compounds' structure–activity relationships led to the development of several subclasses of oxazolidinone derivatives, with varying safety profiles and antimicrobial activity. Two compounds were considered drug candidates: eperezolid (codenamed PNU-100592) and linezolid (PNU-100766).[8][9] In the preclinical stages of development, they were similar in safety and antibacterial activity, so they were taken to Phase I clinical trials to identify any difference in pharmacokinetics.[7][10] Linezolid was found to have a pharmacokinetic advantage—requiring only twice-daily dosage, while eperezolid needed to be given three times a day to achieve similar exposure—and therefore proceeded to further trials.[8] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved linezolid on April 18, 2000.[11] Approval followed in Brazil (June 2000),[12] the United Kingdom (January 2001),[9][13] Japan and Canada (April 2001),[14][15][16] Europe (throughout 2001),[17] and other countries in Latin America and Asia.[15]

As of 2009, linezolid is the only oxazolidinone antibiotic available.[18] Other members of this class have entered development, such as posizolid (AZD2563),[19] ranbezolid (RBx 7644),[20] torezolid (TR-701),[18][21] and radezolid (RX-1741).[22]

Spectrum of activity

Linezolid is effective against all clinically important Gram-positive bacteria—those whose cell wall contains a thick layer of peptidoglycan and no outer membrane—notably Enterococcus faecium and Enterococcus faecalis (including vancomycin-resistant enterococci), Staphylococcus aureus (including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, MRSA), Streptococcus agalactiae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Streptococcus pyogenes, the viridans group streptococci, Listeria monocytogenes, and Corynebacterium species (the latter being among the most susceptible to linezolid, with minimum inhibitory concentrations routinely below 0.5 mg/L).[1][5][23] Linezolid is also highly active in vitro against several mycobacteria.[5] It appears to be very effective against Nocardia, but because of high cost and potentially serious adverse effects, authors have recommended that it be combined with other antibiotics or reserved for cases that have failed traditional treatment.[24]

Linezolid is considered bacteriostatic against most organisms—that is, it stops their growth and reproduction without actually killing them—but has some bactericidal (killing) activity against streptococci.[1][25] Some authors have noted that, despite its bacteriostatic effect in vitro, linezolid "behaves" as a bactericidal antibiotic in vivo because it inhibits the production of toxins by staphylococci and streptococci.[8] It also has a post-antibiotic effect lasting one to four hours for most bacteria, meaning that bacterial growth is temporarily suppressed even after the drug is discontinued.[26]

Gram-negative bacteria

Linezolid has no clinically significant effect on most Gram-negative bacteria. Pseudomonas and the Enterobacteriaceae, for instance, are not susceptible.[25] In vitro, it is active against Pasteurella multocida,[1][27] Fusobacterium, Moraxella catarrhalis, Legionella, Bordetella, and Elizabethkingia meningoseptica, and moderately active (having a minimum inhibitory concentration for 90% of strains of 8 mg/L) against Haemophilus influenzae.[25][28] It has also been used to great effect as a second-line treatment for Capnocytophaga infections.[29][30]

Comparable antibiotics

Linezolid's spectrum of activity against Gram-positive bacteria is similar to that of the glycopeptide antibiotic vancomycin, which has long been the standard for treatment of MRSA infections, and the two drugs are often compared.[26][31] Other comparable antibiotics include teicoplanin (trade name Targocid, a glycopeptide like vancomycin), quinupristin/dalfopristin (Synercid, a combination of two streptogramins, not active against E. faecalis),[7] and daptomycin (Cubicin, a lipopeptide), and some agents still being developed, such as ceftobiprole, dalbavancin, and telavancin. Linezolid is the only one that can be taken by mouth.[26] In the future, oritavancin and iclaprim may be useful oral alternatives to linezolid—both are in the early stages of clinical development.[26]

Therapeutic uses

The main indication of linezolid is the treatment of severe infections caused by Gram-positive bacteria that are resistant to other antibiotics; it should not be used against bacteria that are sensitive to drugs with a narrower spectrum of activity, such as penicillins and cephalosporins. In both the popular press and the scientific literature, linezolid has been called a "reserve antibiotic"—one that should be used sparingly so that it will remain effective as a drug of last resort against potentially intractable infections.[32][33]

In the United States, the FDA-approved indications for linezolid use are: vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus infection, with or without bacterial invasion of the bloodstream; hospital- and community-acquired pneumonia caused by S. aureus or S. pneumoniae; complicated skin and skin structure infections (cSSSI) caused by susceptible bacteria, including diabetic foot infection, unless complicated by osteomyelitis (infection of the bone and bone marrow); and uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections caused by S. pyogenes or S. aureus. The manufacturer advises against the use of linezolid for community-acquired pneumonia or uncomplicated skin and soft tissue infections caused by MRSA.[1] In the United Kingdom, pneumonia and cSSSIs are the only indications noted in the product labeling.[13] Linezolid appears to be as safe and effective for use in children and newborns as it is in adults.[26]

Skin and soft tissue infections

A large meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials found linezolid to be more effective than glycopeptide antibiotics (such as vancomycin and teicoplanin) and beta-lactam antibiotics in the treatment of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) caused by Gram-positive bacteria,[34] and smaller studies appear to confirm its superiority over teicoplanin in the treatment of all serious Gram-positive infections.[35]

In the treatment of diabetic foot infections, linezolid appears to be cheaper and more effective than vancomycin.[36] In a 2004 open-label study, it was as effective as ampicillin/sulbactam and co-amoxiclav, and far superior in patients with foot ulcers and no osteomyelitis, but with significantly higher rates of adverse effects.[37][38] A 2008 meta-analysis of 18 randomized controlled trials, however, found that linezolid treatment failed as often as other antibiotics, regardless of whether patients had osteomyelitis.[39]

Some authors have recommended that combinations of cheaper or more cost-effective drugs (such as co-trimoxazole with rifampicin or clindamycin) be tried before linezolid in the treatment of SSTIs when susceptibility of the causative organism allows it.[38][40]

Pneumonia

There appears to be no significant difference in treatment success rates between linezolid, glycopeptides, or appropriate beta-lactam antibiotics in the treatment of pneumonia.[34] Clinical guidelines for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia developed by the American Thoracic Society and the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend that linezolid be reserved for cases in which MRSA has been confirmed as the causative organism, or when MRSA infection is suspected based on the clinical presentation.[41] The guidelines of the British Thoracic Society do not recommend it as first-line treatment, but rather as an alternative to vancomycin.[42] Linezolid is also an acceptable second-line treatment for community-acquired pneumococcal pneumonia when penicillin resistance is present.[41]

U.S. guidelines recommend either linezolid or vancomycin as the first-line treatment for hospital-acquired (nosocomial) MRSA pneumonia.[43] Some studies have suggested that linezolid is better than vancomycin against nosocomial pneumonia, particularly ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by MRSA, perhaps because the penetration of linezolid into bronchial fluids is much higher than that of vancomycin. Several issues in study design have been raised, however, calling into question results that suggest the superiority of linezolid.[38] Regardless, linezolid's advantages include its high bioavailability (because it allows easy switching to oral therapy), and the fact that poor kidney function is not an obstacle to use (whereas achieving the correct dosage of vancomycin in patients with renal insufficiency is very difficult).[43]

Off-label use

It is traditionally believed that so-called "deep" infections—such as osteomyelitis or infective endocarditis—should be treated with bactericidal antibiotics, not bacteriostatic ones. Nevertheless, preclinical studies were conducted to assess the efficacy of linezolid for these infections,[8] and the drug has been used successfully to treat them in clinical practice. Linezolid appears to be a reasonable therapeutic option for infective endocarditis caused by multi-resistant Gram-positive bacteria, despite a lack of high-quality evidence to support this use.[45][46] Results in the treatment of enterococcal endocarditis have varied, with some cases treated successfully and others not responding to therapy.[47][48][49][50][51][52] Low- to medium-quality evidence is also mounting for its use in bone and joint infections, including chronic osteomyelitis, although adverse effects are a significant concern when long-term use is necessary.[53][54][55][56][57][58]

In combination with other drugs, linezolid has been used to treat tuberculosis.[59] The optimal dose for this purpose has not been established. In adults, daily and twice-daily dosing have been used to good effect. Many months of treatment are often required, and the rate of adverse effects is high regardless of dosage.[60][61] There is not enough reliable evidence of efficacy and safety to support this indication as a routine use.[26]

Linezolid has been studied as an alternative to vancomycin in the treatment of febrile neutropenia in cancer patients when Gram-positive infection is suspected.[62] It is also one of few antibiotics that diffuse into the vitreous humor, and may therefore be effective in treating endophthalmitis (inflammation of the inner linings and cavities of the eye) caused by susceptible bacteria. Again, there is little evidence for its use in this setting, as infectious endophthalmitis is treated widely and effectively with vancomycin injected directly into the eye.[38]

Infections of the central nervous system

In animal studies of meningitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, linezolid was found to penetrate well into cerebrospinal fluid, but its effectiveness was inferior to that of other antibiotics.[5][63] There does not appear to be enough high-quality evidence to support the routine use of linezolid to treat bacterial meningitis. Nonetheless, it has been used successfully in many cases of central nervous system infection—including meningitis—caused by susceptible bacteria, and has also been suggested as a reasonable choice for this indication when treatment options are limited or when other antibiotics have failed.[29][64] The guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of America recommend linezolid as the first-line drug of choice for VRE meningitis, and as an alternative to vancomycin for MRSA meningitis.[65] Linezolid appears superior to vancomycin in treating community-acquired MRSA infections of the central nervous system, although very few cases of such infections have been published (as of 2009).[66]

In March 2007, the FDA reported the results of a randomized, open-label, phase III clinical trial comparing linezolid to vancomycin in the treatment of catheter-related bloodstream infections. Patients treated with vancomycin could be switched to oxacillin or dicloxacillin if the bacteria that caused their infection was found to be susceptible, and patients in both groups (linezolid and vancomycin) could receive specific treatment against Gram-negative bacteria if necessary.[67] The study itself was published in January 2009.[68]

Linezolid was associated with significantly greater mortality than the comparator antibiotics. When data from all participants were pooled, the study found that 21.5% of those given linezolid died, compared to 16% of those not receiving it. The difference was found to be due to the inferiority of linezolid in the treatment of Gram-negative infections alone or mixed Gram-negative/Gram-positive infections. In participants whose infection was due to Gram-positive bacteria alone, linezolid was as safe and effective as vancomycin.[67][68] In light of these results, the FDA issued an alert reminding healthcare professionals that linezolid is not approved for the treatment of catheter-related infections or infections caused by Gram-negative organisms, and that more appropriate therapy should be instituted whenever a Gram-negative infection is confirmed or suspected.[67]

Adverse effects

When used for short periods, linezolid is a relatively safe drug.[31] Common side effects of linezolid use (those occurring in more than 1% of people taking linezolid) include diarrhea (reported by 3–11% of clinical trial participants), headache (1–11%), nausea (3–10%), vomiting (1–4%), rash (2%), constipation (2%), altered taste perception (1–2%), and discoloration of the tongue (0.2–1%).[2] Fungal infections such as thrush and vaginal candidiasis may also occur as linezolid suppresses normal bacterial flora and opens a niche for fungi (so-called antibiotic candidiasis).[2] Less common (and potentially more serious) adverse effects include allergic reactions, pancreatitis, and elevated transaminases, which may be a sign of liver damage.[2][9] Unlike some antibiotics, such as erythromycin and the quinolones, linezolid has no effect on the QT interval, a measure of cardiac electrical conduction.[9][69] Adverse effects in children are similar to those that occur in adults.[69]

Like nearly all antibiotics, linezolid has been associated with Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea (CDAD) and pseudomembranous colitis, although the latter is uncommon, occurring in about one in two thousand patients in clinical trials.[2][9][69][70] C. difficile appears to be susceptible to linezolid in vitro, and linezolid was even considered as a possible treatment for CDAD.[71]

As of 2009, linezolid is a "black triangle drug" in the United Kingdom, meaning that it is under intensive postmarketing surveillance by the Commission on Human Medicines of the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency.[13]

Long-term use

Bone marrow suppression, characterized particularly by thrombocytopenia (low platelet count), may occur during linezolid treatment; it appears to be the only adverse effect that occurs significantly more frequently with linezolid than with glycopeptides or beta-lactams.[34] It is uncommon in patients who receive the drug for 14 days or fewer, but occurs much more frequently in patients who receive longer courses or who have renal failure.[9][72] A 2004 case report suggested that pyridoxine (a form of vitamin B6) could reverse the anemia and thrombocytopenia caused by linezolid,[73] but a later, larger study found no protective effect.[74]

Long-term use of linezolid has also been associated with peripheral neuropathy and optic neuropathy, which is most common after several months of treatment and may be irreversible.[75][76][77][78] Although the mechanism of injury is still poorly understood, mitochondrial toxicity has been proposed as a cause;[79][80] linezolid is toxic to mitochondria, probably because of the similarity between mitochondrial and bacterial ribosomes.[81] Lactic acidosis, a potentially life-threatening buildup of lactic acid in the body, may also occur due to mitochondrial toxicity.[79] Because of these long-term effects, the manufacturer recommends weekly complete blood counts during linezolid therapy to monitor for possible bone marrow suppression, and recommends that treatment last no more than 28 days.[1][9] A more extensive monitoring protocol for early detection of toxicity in seriously ill patients receiving linezolid has been developed and proposed by a team of researchers in Melbourne, Australia. The protocol includes twice-weekly blood tests and liver function tests; measurement of serum lactate levels, for early detection of lactic acidosis; a review of all medications taken by the patient, interrupting the use of those that may interact with linezolid; and periodic eye and neurological exams in patients set to receive linezolid for longer than four weeks.[82]

The adverse effects of long-term linezolid therapy were first identified during postmarketing surveillance. Bone marrow suppression was not identified during Phase III trials, in which treatment did not exceed 21 days. Although some participants of early trials did experience thrombocytopenia, it was found to be reversible and did not occur significantly more frequently than in controls (participants not taking linezolid).[5] There have also been postmarketing reports of seizures, and, as of July 2009, a single case each of Bell's palsy (paralysis of the facial nerve) and kidney toxicity.[69]

Chemistry

At physiological pH, linezolid exists in an uncharged state. It is moderately water-soluble (approximately 3 mg/mL), with a logP of 0.55.[26]

![Skeletal formula of N-{[(5S)-3-[3-fluoro-4-(morpholin-4-yl)phenyl]-2-oxo-1,3-oxazolidin-5-yl]methyl}acetamide, highlighting the morpholino and fluoro groups in orange, with the rest in blue. The carbon atoms of the parent chain are numbered.](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/180px-Linezolid_showing_oxazolidinone_pharmacophore.svg.png)

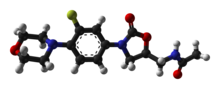

The oxazolidinone pharmacophore—the chemical "template" essential for antimicrobial activity—consists of a 1,3-oxazolidin-2-one moiety with an aryl group at position 3 and an S-methyl group, with another substituent attached to it, at position 5 (the R-enantiomers of all oxazolidinones are devoid of antibiotic properties).[4] In addition to this essential core, linezolid also contains several structural characteristics that improve its effectiveness and safety. An acetamide substituent on the 5-methyl group is the best choice in terms of antibacterial efficacy, and is used in all of the more active oxazolidinones developed thus far; in fact, straying too far from an acetamide group at this position makes the drug lose its antimicrobial power, although weak to moderate activity is maintained when some isosteric groups are used. A fluorine atom at the 3′ position practically doubles in vitro and in vivo activity, and the electron-donating nitrogen atom in the morpholine ring helps maintain high antibiotic potency and an acceptable safety profile.[4][8]

The anticoagulant rivaroxaban (Xarelto) bears a striking structural similarity to linezolid; both drugs share the oxazolidinone pharmacophore, differing in only three areas (an extra ketone and chlorothiophene, and missing the fluorine atom). However this similarity appears to carry no clinical significance.[83]

Synthesis

Linezolid is a completely synthetic drug: it does not occur in nature (unlike erythromycin and many other antibiotics) and was not developed by building upon a naturally occurring skeleton (unlike most beta-lactams, which are semisynthetic). Many approaches are available for oxazolidinone synthesis, and several routes for the synthesis of linezolid have been reported in the chemistry literature.[4][84] Despite good yields, the original method (developed by Upjohn for pilot plant-scale production of linezolid and eperezolid) is lengthy, requires the use of expensive chemicals—such as palladium on carbon and the highly sensitive reagents methanesulfonyl chloride and n-butyllithium—and needs low-temperature conditions.[4][84][85] Much of the high cost of linezolid has been attributed to the expense of its synthesis.[85] A somewhat more concise and cost-effective route better suited to large-scale production was patented by Upjohn in 1998.[8][86]

Later syntheses have included an "atom-economical" method starting from D-mannitol, developed by Indian pharmaceutical company Dr. Reddy's and reported in 1999,[87] and a route starting from (S)-glyceraldehyde acetonide (prepared from vitamin C), developed by a team of researchers from Hunan Normal University in Changsha, Hunan, China.[84] On June 25, 2008, during the 12th Annual Green Chemistry and Engineering Conference in New York, Pfizer reported the development of their "second-generation" synthesis of linezolid: a convergent, green synthesis starting from (S)-epichlorohydrin, with higher yield and a 56% reduction in total waste.[88]

Pharmacokinetics

One of the advantages of linezolid is its high bioavailability (close to 100%) when given by mouth: the entire dose reaches the bloodstream, as if it had been given intravenously. This means that people receiving intravenous linezolid may be switched to oral linezolid as soon as their condition allows it, whereas comparable antibiotics (such as vancomycin and quinupristin/dalfopristin) can only be given intravenously.[89] Taking linezolid with food somewhat slows its absorption, but the area under the curve is not affected.[26]

Linezolid has low plasma protein binding (approximately 31%, but highly variable) and an apparent volume of distribution at steady state of around 40–50 liters.[2] Peak serum concentrations (Cmax) are reached one to two hours after administration of the drug. Linezolid is readily distributed to all tissues in the body apart from bone matrix and white adipose tissue.[8] Notably, the concentration of linezolid in the epithelial lining fluid of the lower respiratory tract is at least equal to, and often higher than, that achieved in serum (some authors have reported bronchial fluid concentrations up to four times higher than serum concentrations), which may account for its efficacy in treating pneumonia. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) concentrations vary; peak CSF concentrations are lower than serum ones, due to slow diffusion across the blood-brain barrier, and trough concentrations in the CSF are higher for the same reason.[26] The average half-life is three hours in children, four hours in teenagers, and five hours in adults.[1]

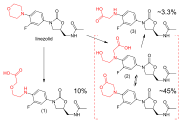

Linezolid is metabolized in the liver, by oxidation of the morpholine ring, without involvement of the cytochrome P450 system. This metabolic pathway leads to two major inactive metabolites (which each account for around 45% and 10% of an excreted dose at steady state), one minor metabolite, and several trace metabolites, none of which accounts for more than 1% of an excreted dose.[90] Clearance of linezolid varies with age and gender; it is fastest in children (which accounts for the shorter half-life), and appears to be 20% lower in women than in men.[1][90][91]

Use in special populations

In adults and children over the age of 12, linezolid is usually given every 12 hours, whether orally or intravenously.[5][89] In younger children and infants, it is given every eight hours.[92] No dosage adjustments are required in the elderly, in people with mild-to-moderate liver failure, or in those with impaired kidney function.[2] In people requiring hemodialysis, care should be taken to give linezolid after a session, because dialysis removes 30–40% of a dose from the body; no dosage adjustments are needed in people undergoing continuous hemofiltration,[2] although more frequent administration may be warranted in some cases.[26] According to one study, linezolid may need to be given more frequently than normal in people with burns affecting more than 20% of body area, due to increased nonrenal clearance of the drug.[93]

Linezolid is in U.S. pregnancy category C, meaning there have been no adequate studies of its safety when used by pregnant women, and although animal studies have shown mild toxicity to the fetus, the benefits of using the drug may outweigh its risks.[1] It also passes into breast milk, although the clinical significance of this (if any) is unknown.[28]

Mechanism of action

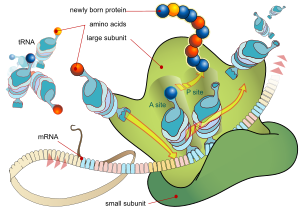

The oxazolidinones are protein synthesis inhibitors: they stop the growth and reproduction of bacteria by disrupting translation of messenger RNA (mRNA) into proteins in the ribosome. Although its mechanism of action is not fully understood,[94] linezolid appears to work on the first step of protein synthesis, initiation, unlike most other protein synthesis inhibitors, which inhibit elongation.[89][95]

It does so by preventing the formation of the initiation complex, composed of the 30S and 50S subunits of the ribosome, tRNA, and mRNA. Linezolid binds to the 23S portion of the 50S subunit (the center of peptidyl transferase activity),[96] close to the binding sites of chloramphenicol, lincomycin, and other antibiotics. Due to this unique mechanism of action, cross-resistance between linezolid and other protein synthesis inhibitors is highly infrequent or nonexistent.[5][26]

In 2008, the crystal structure of linezolid bound to the 50S subunit of a ribosome from the archaean Haloarcula marismortui was elucidated by a team of scientists from Yale University and deposited in the Protein Data Bank.[97] Another team in 2008 determined the structure of linezolid bound to a 50S subunit of Deinococcus radiodurans. The authors proposed a refined model for the mechanism of action of oxazolidinones, finding that linezolid occupies the A site of the 50S ribosomal subunit, inducing a conformational change that prevents tRNA from entering the site and ultimately forcing tRNA to separate from the ribosome.[98]

Resistance

Acquired resistance to linezolid was reported as early as 1999, in two patients with severe, multidrug-resistant Enterococcus faecium infection who received the drug through a compassionate use program.[25] Linezolid-resistant Staphylococcus aureus was first isolated in 2001.[99]

In the United States, resistance to linezolid has been monitored and tracked since 2004 through a program named LEADER, which (as of 2007) was conducted in 60 medical institutions throughout the country. Resistance has remained stable and extremely low—less than one-half of one percent of isolates overall, and less than one-tenth of one percent of S. aureus samples.[23] A similar, worldwide program—the "Zyvox Annual Appraisal of Potency and Spectrum Study", or ZAAPS—has been conducted since 2002. As of 2007, overall resistance to linezolid in 23 countries was less than 0.2%, and nonexistent among streptococci. Resistance was only found in Brazil, China, Ireland, and Italy, among coagulase-negative staphylococci (0.28% of samples resistant), enterococci (0.11%), and S. aureus (0.03%).[100] In the United Kingdom and Ireland, no resistance was found in staphylococci collected from bacteremia cases between 2001 and 2006,[101] although resistance in enterococci has been reported.[102] Some authors have predicted that resistance in E. faecium will increase if linezolid use continues at current levels or increases.[103]

Mechanism

The intrinsic resistance of most Gram-negative bacteria to linezolid is due to the activity of efflux pumps, which actively "pump" linezolid out of the cell faster than it can accumulate.[8][104]

Gram-positive bacteria usually develop resistance to linezolid as the result of a point mutation known as G2576T, in which a guanine base is replaced with thymine in base pair 2576 of the genes coding for 23S ribosomal RNA.[105][106] This is the most common mechanism of resistance in staphylococci, and the only one known to date in isolates of E. faecium.[103] Other mechanisms have been identified in Streptococcus pneumoniae (including mutations in an RNA methyltransferase that methylates G2445 of the 23S rRNA and mutations causing increased expression of ABC transporter genes)[107] and in Staphylococcus epidermidis.[108][109]

Interactions

Linezolid is a weak monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), and should not be used concomitantly with other MAOIs, large amounts of tyramine-rich foods (such as pork, aged cheeses, alcoholic beverages, or smoked and pickled foods), or serotonergic drugs. There have been postmarketing reports of serotonin syndrome when linezolid was given with or soon after the discontinuation of serotonergic drugs, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as paroxetine and sertraline.[9][110][111][112] It may also enhance the blood pressure-increasing effects of sympathomimetic drugs such as pseudoephedrine or phenylpropanolamine.[5][113] It should also not be given in combination with pethidine (meperidine) under any circumstance due to the risk of serotonin syndrome.

Linezolid does not inhibit or induce the cytochrome P450 (CYP) system, which is responsible for the metabolism of many commonly used drugs, and therefore does not have any CYP-related interactions.[1]

Economic considerations

Linezolid is quite expensive; a course of treatment may cost several thousand U.S. dollars for the drug alone, not to mention other costs (such as those associated with hospital stay). However, because intravenous linezolid may be switched to an oral formulation (tablets or oral solution) without jeopardizing efficacy, patients may be discharged from hospital relatively early and continue treatment at home, whereas home treatment with injectable antibiotics may be impractical.[3] Reducing the length of hospital stay reduces the overall cost of treatment, even though linezolid may have a higher acquisition cost—that is, it may be more expensive—than comparable antibiotics.

Studies have been conducted in several countries with different health care system models to assess the cost-effectiveness of linezolid compared to glycopeptides such as vancomycin or teicoplanin. In most countries, linezolid was more cost-effective than comparable antibiotics for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia and complicated skin and skin structure infections, either due to higher cure and survival rates or lower overall treatment costs.[3]

In 2009, Pfizer paid $2.3 billion and entered a corporate integrity agreement to settle charges that it had misbranded and illegally promoted four drugs, and caused false claims to be submitted to government healthcare programs for uses that were not medically accepted.[114] $1.3 billion were to settle criminal charges of illegally marketing the anti-inflammatory valdecoxib, while $1 billion was paid in civil fines regarding illegal marketing of three other drugs, including Zyvox.[115]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Pfizer (June 20, 2008). "ZYVOX (linezolid) Label Information" (PDF). http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2008/021130s016,021131s013,021132s014lbl.pdf. Retrieved 2008-08-24.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Lexi-Comp (August 2008). "Linezolid". The Merck Manual Professional. http://www.merck.com/mmpe/lexicomp/linezolid.html. Retrieved on May 14, 2009.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Grau S, Rubio-Terrés C (April 2008). "Pharmacoeconomics of linezolid". Expert Opinion on Pharmacotherapy 9 (6): 987–1000. doi:10.1517/14656566.9.6.987. ISSN 1465-6566. PMID 18377341.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 Brickner SJ (1996). "Oxazolidinone antibacterial agents". Current Pharmaceutical Design 2 (2): 175–94. http://books.google.com/?id=_HFitfA4OcUC&pg=PA175&lpg=PA175. Detailed review of the discovery and development of the whole oxazolidinone class, including information on synthesis and structure-activity relationships.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Moellering RC (January 2003). "Linezolid: the first oxazolidinone antimicrobial". Annals of Internal Medicine 138 (2): 135–42. ISSN 0003-4819. PMID 12529096. http://www.annals.org/cgi/reprint/138/2/135.pdf.

- ↑ Slee AM, Wuonola MA, McRipley RJ, et al. (November 1987). "Oxazolidinones, a new class of synthetic antibacterial agents: in vitro and in vivo activities of DuP 105 and DuP 721". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 31 (11): 1791–7. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 3435127. PMC 175041. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/reprint/31/11/1791.pdf.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Livermore DM (September 2000). "Quinupristin/dalfopristin and linezolid: where, when, which and whether to use?". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 46 (3): 347–50. doi:10.1093/jac/46.3.347. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 10980159. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/46/3/347.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 Barbachyn MR, Ford CW (May 2003). "Oxazolidinone structure-activity relationships leading to linezolid". Angewandte Chemie (International Edition in English) 42 (18): 2010–23. doi:10.1002/anie.200200528. ISSN 1433-7851. PMID 12746812.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 French G (May 2003). "Safety and tolerability of linezolid" (Free full text). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 51 (Suppl 2): ii45–53. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg253. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 12730142. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12730142. Review. Includes extensive discussion of the hematological adverse effects of linezolid.

- ↑ Ford CW, Zurenko GE, Barbachyn MR (August 2001). "The discovery of linezolid, the first oxazolidinone antibacterial agent". Current Drug Targets – Infectious Disorders 1 (2): 181–99. doi:10.2174/1568005014606099. ISSN 1568-0053. PMID 12455414.

- ↑ "Drug Approval Package: Zyvox". FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. November 20, 2001. Archived from the original on 2008-01-10. http://web.archive.org/web/20080110042651/http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/nda/2000/21130_Zyvox.htm. Retrieved 2009-01-17. Comprehensive review of the FDA approval process. Includes detailed reviews of the chemistry and pharmacology of linezolid, correspondence between the FDA and Pharmacia & Upjohn, and administrative documents.

- ↑ ANVISA (June 5, 2000). "Resolução nº 474, de 5 de junho de 2000" (in Portuguese). National Health Surveillance Agency. http://www.anvisa.gov.br/legis/resol/2000/474_00re.htm. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 [No authors listed] (2009-06-24). "Zyvox 600 mg Film-Coated Tablets, 100 mg/5 ml Granules for Oral Suspension, 2 mg/ml Solution for Infusion – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. http://emc.medicines.org.uk/medicine/9857. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ↑ Irinoda K, Nomura S, Hashimoto M (October 2002). "[Antimicrobial and clinical effect of linezolid (ZYVOX), new class of synthetic antibacterial drug]" (in Japanese). Nippon Yakurigaku Zasshi 120 (4): 245–52. doi:10.1254/fpj.120.245. ISSN 0015-5691. PMID 12425150.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Canada Approves Marketing Of Zyvoxam (Linezolid) For Gram Positive Infections". Press release. May 8, 2001. http://www.docguide.com/news/content.nsf/news/917912FCF5C34DCA85256A46006E24B0. Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- ↑ Karlowsky JA, Kelly LJ, Critchley IA, Jones ME, Thornsberry C, Sahm DF (June 2002). "Determining Linezolid's baseline in vitro activity in Canada using gram-positive clinical isolates collected prior to its national release" (Free full text). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 46 (6): 1989–92. doi:10.1128/AAC.46.6.1989-1992.2002. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 12019122. PMC 127260. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12019122.

- ↑ "Pharmacia Corporation Reports 17% Increase In Second-Quarter Earnings-Per-Share Driven By 61% Increase In Pharmaceutical Earnings". Press release. July 25, 2001. http://www.prnewswire.ca/cgi-bin/stories.pl?ACCT=104&STORY=/www/story/07-25-2001/0001540814&EDATE=. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Livermore DM, Mushtaq S, Warner M, Woodford N (April 2009). "Activity of oxazolidinone TR-700 against linezolid-susceptible and -resistant staphylococci and enterococci". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 63 (4): 713–5. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp002. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 19164418.

- ↑ Howe RA, Wootton M, Noel AR, Bowker KE, Walsh TR, MacGowan AP (November 2003). "Activity of AZD2563, a novel oxazolidinone, against Staphylococcus aureus strains with reduced susceptibility to vancomycin or linezolid" (Free full text). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 47 (11): 3651–2. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.11.3651-3652.2003. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 14576139. PMC 253812. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=14576139.

- ↑ Kalia V, Miglani R, Purnapatre KP, et al. (April 2009). "Mode of action of Ranbezolid against staphylococci and structural modeling studies of its interaction with ribosomes". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 53 (4): 1427–33. doi:10.1128/AAC.00887-08. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 19075051.

- ↑ "Trius Completes Enrollment In Phase 2 Clinical Trial Evaluating Torezolid (TR-701) In Patients With Complicated Skin And Skin Structure Infections". Press release. 2009-01-27. http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/136728.php. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ "Rx 1741". Rib-X Pharmaceuticals. 2009. http://www.rib-x.com/pipeline/rx_1741. Retrieved 2009-05-17.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Jones RN, Stilwell MG, Hogan PA, Sheehan DJ (April 2007). "Activity of linezolid against 3,251 strains of uncommonly isolated gram-positive organisms: report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 51 (4): 1491–3. doi:10.1128/AAC.01496-06. PMID 17210770.

- ↑ Jodlowski TZ, Melnychuk I, Conry J (October 2007). "Linezolid for the treatment of Nocardia spp. infections". Annals of Pharmacotherapy 41 (10): 1694–9. doi:10.1345/aph.1K196. ISSN 1060-0280. PMID 17785610.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 [No authors listed] (2001). "Linezolid". Drugs & Therapy Perspectives 17 (9): 1–6. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/406493. Free full text with registration at Medscape.

- ↑ 26.00 26.01 26.02 26.03 26.04 26.05 26.06 26.07 26.08 26.09 26.10 Herrmann DJ, Peppard WJ, Ledeboer NA, Theesfeld ML, Weigelt JA, Buechel BJ (December 2008). "Linezolid for the treatment of drug-resistant infections". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 6 (6): 825–48. doi:10.1586/14787210.6.6.825. ISSN 1478-7210. PMID 19053895.

- ↑ [No authors listed] (August 5, 2008). "Animal Bites and Pasteurella multocida: Information for Healthcare Staff". Health Protection Agency. http://www.hpa.org.uk/webw/HPAweb&HPAwebStandard/HPAweb_C/1195733833519?p=1203409654995. Retrieved on 2009-05-15.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Davaro RE, Glew RH, Daly JS (2004). "Oxazolidinones, quinupristin-dalfopristin, and daptomycin". In Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR. Infectious diseases. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 241–3. ISBN 0-7817-3371-5. http://books.google.com/books?id=91altE1evAsC&pg=PP241. Retrieved 2009-06-20.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Sabbatani S, Manfredi R, Frank G, Chiodo F (June 2005). "Linezolid in the treatment of severe central nervous system infections resistant to recommended antimicrobial compounds". Le Infezioni in Medicina 13 (2): 112–9. ISSN 1124-9390. PMID 16220032. http://www.infezmed.it/VisualizzaUnArticolo.aspx?Anno=2005&numero=2&ArticoloDaVisualizzare=Vol_13_2_2005_8.

- ↑ Geisler WM, Malhotra U, Stamm WE (December 2001). "Pneumonia and sepsis due to fluoroquinolone-resistant Capnocytophaga gingivalis after autologous stem cell transplantation" (Free full text). Bone Marrow Transplantation 28 (12): 1171–3. doi:10.1038/sj.bmt.1703288. ISSN 0268-3369. PMID 11803363.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Marino PL, Sutin KM (2007). "Antimicrobial therapy". The ICU book. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 817. ISBN 0-7817-4802-X.

- ↑ Wroe, David (2002-02-28). "An antibiotic to fight immune bugs". The Age. http://www.theage.com.au/articles/2002/02/27/1014704966995.html. Retrieved 2009-05-16.

- ↑ Wilson AP, Cepeda JA, Hayman S, Whitehouse T, Singer M, Bellingan G (August 2006). "In vitro susceptibility of Gram-positive pathogens to linezolid and teicoplanin and effect on outcome in critically ill patients" (Free full text). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 58 (2): 470–3. doi:10.1093/jac/dkl233. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 16735420. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16735420.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Falagas ME, Siempos II, Vardakas KZ (January 2008). "Linezolid versus glycopeptide or beta-lactam for treatment of Gram-positive bacterial infections: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials". Lancet Infectious Diseases 8 (1): 53–66. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70312-2. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 18156089. Structured abstract with quality assessment available at DARE.

- ↑ Tascini C, Gemignani G, Doria R, et al. (June 2009). "Linezolid treatment for gram-positive infections: a retrospective comparison with teicoplanin". Journal of Chemotherapy (Florence, Italy) 21 (3): 311–6. ISSN 1120-009X. PMID 19567352.

- ↑ Chow I, Lemos EV, Einarson TR (2008). "Management and prevention of diabetic foot ulcers and infections: a health economic review". PharmacoEconomics 26 (12): 1019–35. doi:10.2165/0019053-200826120-00005. ISSN 1170-7690. PMID 19014203.

- ↑ Lipsky BA, Itani K, Norden C (January 2004). "Treating foot infections in diabetic patients: a randomized, multicenter, open-label trial of linezolid versus ampicillin-sulbactam/amoxicillin-clavulanate". Clinical Infectious Diseases 38 (1): 17–24. doi:10.1086/380449. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 14679443.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 Pigrau C, Almirante B (April 2009). "[Oxazolidinones, glycopeptides and cyclic lipopeptides]" (in Spanish). Enfermedades Infecciosas y Microbiología Clínica 27 (4): 236–46. doi:10.1016/j.eimc.2009.02.004. PMID 19406516. http://www.elsevier.es/revistas/ctl_servlet?_f=7064&articuloid=13136682.

- ↑ Vardakas KZ, Horianopoulou M, Falagas ME (June 2008). "Factors associated with treatment failure in patients with diabetic foot infections: An analysis of data from randomized controlled trials". Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice 80 (3): 344–51. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2008.01.009. ISSN 0168-8227. PMID 18291550.

- ↑ Grammatikos A, Falagas ME (2008). "Linezolid for the treatment of skin and soft tissue infection". Expert Review of Dermatology 3 (5): 539–48. doi:10.1586/17469872.3.5.539.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. (March 2007). "Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults". Clinical Infectious Diseases 44 (Suppl 2): S27–72. doi:10.1086/511159. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 17278083.

- ↑ BTS Pneumonia Guidelines Committee (2004-04-30). "BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults – 2004 update". British Thoracic Society. http://www.brit-thoracic.org.uk/Portals/0/Clinical%20Information/Pneumonia/Guidelines/MACAPrevisedApr04.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-30.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 American Thoracic Society, Infectious Diseases Society of America (February 2005). "Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia" (Free full text). American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 171 (4): 388–416. doi:10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. ISSN 1073-449X. PMID 15699079. http://ajrccm.atsjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15699079.

- ↑ Koya D, Shibuya K, Kikkawa R, Haneda M (December 2004). "Successful recovery of infective endocarditis-induced rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis by steroid therapy combined with antibiotics: a case report" (Free full text). BMC Nephrology 5 (1): 18. doi:10.1186/1471-2369-5-18. PMID 15610562. PMC 544880. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2369/5/18.

- ↑ Pankey GA, Sabath LD (March 2004). "Clinical relevance of bacteriostatic versus bactericidal mechanisms of action in the treatment of Gram-positive bacterial infections". Clinical Infectious Diseases 38 (6): 864–70. doi:10.1086/381972. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 14999632.

- ↑ Falagas ME, Manta KG, Ntziora F, Vardakas KZ (August 2006). "Linezolid for the treatment of patients with endocarditis: a systematic review of the published evidence" (Free full text). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 58 (2): 273–80. doi:10.1093/jac/dkl219. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 16735427. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16735427.

- ↑ Babcock HM, Ritchie DJ, Christiansen E, Starlin R, Little R, Stanley S (May 2001). "Successful treatment of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus endocarditis with oral linezolid". Clinical Infectious Diseases 32 (9): 1373–5. doi:10.1086/319986. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 11303275.

- ↑ Ang JY, Lua JL, Turner DR, Asmar BI (December 2003). "Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium endocarditis in a premature infant successfully treated with linezolid". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 22 (12): 1101–3. doi:10.1097/01.inf.0000101784.83146.0c. ISSN 0891-3668. PMID 14688576.

- ↑ Archuleta S, Murphy B, Keller MJ (September 2004). "Successful treatment of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium endocarditis with linezolid in a renal transplant recipient with human immunodeficiency virus infection". Transplant Infectious Disease 6 (3): 117–9. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3062.2004.00059.x. ISSN 1398-2273. PMID 15569227.

- ↑ Zimmer SM, Caliendo AM, Thigpen MC, Somani J (August 2003). "Failure of linezolid treatment for enterococcal endocarditis". Clinical Infectious Diseases 37 (3): e29–30. doi:10.1086/375877. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 12884185.

- ↑ Tsigrelis C, Singh KV, Coutinho TD, Murray BE, Baddour LM (February 2007). "Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis endocarditis: linezolid failure and strain characterization of virulence factors" (Free full text). Journal of Clinical Microbiology 45 (2): 631–5. doi:10.1128/JCM.02188-06. ISSN 0095-1137. PMID 17182759. PMC 1829077. http://jcm.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17182759.

- ↑ Berdal JE, Eskesen A (2008). "Short-term success, but long-term treatment failure with linezolid for enterococcal endocarditis". Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases 40 (9): 765–6. doi:10.1080/00365540802087209. ISSN 0036-5548. PMID 18609208.

- ↑ Falagas ME, Siempos II, Papagelopoulos PJ, Vardakas KZ (March 2007). "Linezolid for the treatment of adults with bone and joint infections". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 29 (3): 233–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.08.030. ISSN 0924-8579. PMID 17204407. Review.

- ↑ Bassetti M, Vitale F, Melica G, et al. (March 2005). "Linezolid in the treatment of Gram-positive prosthetic joint infections" (Free full text). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 55 (3): 387–90. doi:10.1093/jac/dki016. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 15705640. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15705640.

- ↑ Aneziokoro CO, Cannon JP, Pachucki CT, Lentino JR (December 2005). "The effectiveness and safety of oral linezolid for the primary and secondary treatment of osteomyelitis". Journal of Chemotherapy (Florence, Italy) 17 (6): 643–50. ISSN 1120-009X. PMID 16433195.

- ↑ Senneville E, Legout L, Valette M, et al. (August 2006). "Effectiveness and tolerability of prolonged linezolid treatment for chronic osteomyelitis: a retrospective study". Clinical Therapeutics 28 (8): 1155–63. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2006.08.001. ISSN 0149-2918. PMID 16982292.

- ↑ Rao N, Hamilton CW (October 2007). "Efficacy and safety of linezolid for Gram-positive orthopedic infections: a prospective case series". Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 59 (2): 173–9. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2007.04.006. ISSN 0732-8893. PMID 17574788.

- ↑ Papadopoulos A, Plachouras D, Giannitsioti E, Poulakou G, Giamarellou H, Kanellakopoulou K (April 2009). "Efficacy and tolerability of linezolid in chronic osteomyelitis and prosthetic joint infections: a case-control study". Journal of Chemotherapy (Florence, Italy) 21 (2): 165–9. ISSN 1120-009X. PMID 19423469.

- ↑ von der Lippe B, Sandven P, Brubakk O (February 2006). "Efficacy and safety of linezolid in multidrug resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB)—a report of ten cases". Journal of Infection 52 (2): 92–6. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2005.04.007. ISSN 0163-4453. PMID 15907341.

- ↑ Park IN, Hong SB, Oh YM, et al. (September 2006). "Efficacy and tolerability of daily-half dose linezolid in patients with intractable multidrug-resistant tuberculosis" (Free full text). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 58 (3): 701–4. doi:10.1093/jac/dkl298. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 16857689. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16857689.

- ↑ Fortún J, Martín-Dávila P, Navas E, et al. (July 2005). "Linezolid for the treatment of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis" (Free full text). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 56 (1): 180–5. doi:10.1093/jac/dki148. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 15911549. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15911549.

- ↑ Jaksic B, Martinelli G, Perez-Oteyza J, Hartman CS, Leonard LB, Tack KJ (March 2006). "Efficacy and safety of linezolid compared with vancomycin in a randomized, double-blind study of febrile neutropenic patients with cancer". Clinical Infectious Diseases 42 (5): 597–607. doi:10.1086/500139. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 16447103. Criticism in doi:10.1086/504431; author reply in doi:10.1086/504437.

- ↑ Cottagnoud P, Gerber CM, Acosta F, Cottagnoud M, Neftel K, Täuber MG (December 2000). "Linezolid against penicillin-sensitive and -resistant pneumococci in the rabbit meningitis model" (Free full text). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 46 (6): 981–5. doi:10.1093/jac/46.6.981. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 11102418. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/46/6/981.

- ↑ Ntziora F, Falagas ME (February 2007). "Linezolid for the treatment of patients with central nervous system infection". Annals of Pharmacotherapy 41 (2): 296–308. doi:10.1345/aph.1H307. ISSN 1060-0280. PMID 17284501. Structured abstract with quality assessment available at DARE.

- ↑ Tunkel AR, Hartman BJ, Kaplan SL, et al. (November 2004). "Practice guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis". Clinical Infectious Diseases 39 (9): 1267–84. doi:10.1086/425368. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 15494903.

- ↑ Naesens R, Ronsyn M, Druwé P, Denis O, Ieven M, Jeurissen A (June 2009). "Central nervous system invasion by community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus: case report and review of the literature". Journal of Medical Microbiology 58 (Pt 9): 1247–51. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.011130-0. ISSN 0022-2615. PMID 19528145.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 [No authors listed] (March 16, 2007). "Linezolid (marketed as Zyvox) – Healthcare Professional Sheet". U.S. Food and Drug Administration. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm126262.htm. Retrieved 2009-06-10.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Wilcox MH, Tack KJ, Bouza E, et al. (January 2009). "Complicated skin and skin-structure infections and catheter-related bloodstream infections: noninferiority of linezolid in a phase 3 study". Clinical Infectious Diseases 48 (2): 203–12. doi:10.1086/595686. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 19072714.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 Metaxas EI, Falagas ME (July 2009). "Update on the safety of linezolid". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 8 (4): 485–91. doi:10.1517/14740330903049706. ISSN 1474-0338. PMID 19538105.

- ↑ Zabel LT, Worm S (June 2005). "Linezolid contributed to Clostridium difficile colitis with fatal outcome". Infection 33 (3): 155–7. doi:10.1007/s15010-005-4112-6. ISSN 0300-8126. PMID 15940418.

- ↑ Peláez T, Alonso R, Pérez C, Alcalá L, Cuevas O, Bouza E (May 2002). "In vitro activity of linezolid against Clostridium difficile" (Free full text). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 46 (5): 1617–8. doi:10.1128/AAC.46.5.1617-1618.2002. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 11959617. PMC 127182. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11959617.

- ↑ Lin Y-H, Wu V-C, Tsai I-J, et al. (October 2006). "High frequency of linezolid-associated thrombocytopenia among patients with renal insufficiency". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 28 (4): 345–51. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.04.017. ISSN 0924-8579. PMID 16935472.

- ↑ Spellberg B, Yoo T, Bayer AS (October 2004). "Reversal of linezolid-associated cytopenias, but not peripheral neuropathy, by administration of vitamin B6". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 54 (4): 832–5. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh405. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 15317746. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/54/4/832.

- ↑ Plachouras D, Giannitsioti E, Athanassia S, et al. (November 2006). "No effect of pyridoxine on the incidence of myelosuppression during prolonged linezolid treatment". Clinical Infectious Diseases 43 (9): e89–91. doi:10.1086/508280. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 17029128.

- ↑ Narita M, Tsuji BT, Yu VL (August 2007). "Linezolid-associated peripheral and optic neuropathy, lactic acidosis, and serotonin syndrome". Pharmacotherapy 27 (8): 1189–97. doi:10.1592/phco.27.8.1189. ISSN 0277-0008. PMID 17655517.

- ↑ Bressler AM, Zimmer SM, Gilmore JL, Somani J (August 2004). "Peripheral neuropathy associated with prolonged use of linezolid". Lancet Infectious Diseases 4 (8): 528–31. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01109-0. ISSN 1473-3099. PMID 15288827.

- ↑ Chao CC, Sun HY, Chang YC, Hsieh ST (January 2008). "Painful neuropathy with skin denervation after prolonged use of linezolid". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 79 (1): 97–9. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.127910. ISSN 0022-3050. PMID 17766431. http://jnnp.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17766431.

- ↑ Saijo T, Hayashi K, Yamada H, Wakakura M (June 2005). "Linezolid-induced optic neuropathy". American Journal of Ophthalmology 139 (6): 1114–6. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2004.11.047. ISSN 0002-9394. PMID 15953450.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Soriano A, Miró O, Mensa J (November 2005). "Mitochondrial toxicity associated with linezolid". New England Journal of Medicine 353 (21): 2305–6. doi:10.1056/NEJM200511243532123. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 16306535.

- ↑ Javaheri M, Khurana RN, O'hearn TM, Lai MM, Sadun AA (January 2007). "Linezolid-induced optic neuropathy: a mitochondrial disorder?". British Journal of Ophthalmology 91 (1): 111–5. doi:10.1136/bjo.2006.102541. ISSN 0007-1161. PMID 17179125.

- ↑ McKee EE, Ferguson M, Bentley AT, Marks TA (June 2006). "Inhibition of mammalian mitochondrial protein synthesis by oxazolidinones" (Free full text). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 50 (6): 2042–9. doi:10.1128/AAC.01411-05. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 16723564. PMC 1479116. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16723564.

- ↑ Bishop E, Melvani S, Howden BP, Charles PG, Grayson ML (April 2006). "Good clinical outcomes but high rates of adverse reactions during linezolid therapy for serious infections: a proposed protocol for monitoring therapy in complex patients" (Free full text). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 50 (4): 1599–602. doi:10.1128/AAC.50.4.1599-1602.2006. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 16569895. PMC 1426936. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16569895.

- ↑ European Medicines Agency (2008). "CHP Assessment Report for Xarelto (EMEA/543519/2008)". http://www.emea.europa.eu/humandocs/PDFs/EPAR/xarelto/H-944-en6.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 Xu GY, Zhou Y, Xu MC (2006). "A convenient synthesis of antibacterial linezolid from (S)-glyceraldehyde acetonide". Chinese Chemical Letters 17 (3): 302–4. http://www.imm.ac.cn/journal/ccl/1703/170306-302-b050449-p3.pdf.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Kaiser CR, Cunico W, Pinheiro AC, Oliveira AG, Peralta MA, Souza MV (2007). "[Oxazolidinones: a new class of compounds against tuberculosis"] (in Portuguese). Revista Brasileira de Farmácia 88 (2): 83–8. http://www.abf.org.br/pdf/2007/RBF_V88_N2_2007/PAG83a88_OXAZOLIDINONAS.pdf.

- ↑ US patent 5837870, Pearlman BA, Perrault WR, Barbachyn MR, et al., "Process to prepare oxazolidinones", issued 1997-03-28 Retrieved on 2009-06-13.

- ↑ Lohray BB, Baskaran S, Rao BS, Reddy BY, Rao IN (June 1999). "A short synthesis of oxazolidinone derivatives linezolid and eperezolid: A new class of antibacterials". Tetrahedron Letters 40 (26): 4855–6. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(99)00893-X.

- ↑ Perrault WR, Keeler JB, Snyder WC, et al. (June 25, 2008). "Convergent green synthesis of linezolid (Zyvox)", in 12th Annual Green Chemistry and Engineering Conference, June 24–26, 2008, New York, NY. Retrieved on 2009-06-08.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 Ament PW, Jamshed N, Horne JP (February 2002). "Linezolid: its role in the treatment of gram-positive, drug-resistant bacterial infections". American Family Physician 65 (4): 663–70. ISSN 0002-838X. PMID 11871684. http://www.aafp.org/afp/20020215/663.html.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Slatter JG, Stalker DJ, Feenstra KL, et al. (August 1, 2001). "Pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and excretion of linezolid following an oral dose of [14C]linezolid to healthy human subjects". Drug Metabolism and Disposition 29 (8): 1136–45. ISSN 0090-9556. PMID 11454733. http://dmd.aspetjournals.org/cgi/content/full/29/8/1136.

- ↑ Sisson TL, Jungbluth GL, Hopkins NK (January 2002). "Age and sex effects on the pharmacokinetics of linezolid". European Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 57 (11): 793–7. doi:10.1007/s00228-001-0380-y. ISSN 0031-6970. PMID 11868801.

- ↑ Buck ML (June 2003). "Linezolid use for resistant Gram-positive infections in children". Pediatric Pharmacotherapy 9 (6). http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/alive/pediatrics/PharmNews/200306.pdf. Retrieved 2009-06-08.

- ↑ Lovering AM, Le Floch R, Hovsepian L, et al. (March 2009). "Pharmacokinetic evaluation of linezolid in patients with major thermal injuries". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 63 (3): 553–9. doi:10.1093/jac/dkn541. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 19153078.

- ↑ Skripkin E, McConnell TS, DeVito J, et al. (October 2008). "Rχ-01, a new family of oxazolidinones that overcome ribosome-based linezolid resistance" (Free full text). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 52 (10): 3550–7. doi:10.1128/AAC.01193-07. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 18663023. PMC 2565890. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18663023.

- ↑ Swaney SM, Aoki H, Ganoza MC, Shinabarger DL (December 1, 1998). "The oxazolidinone linezolid inhibits initiation of protein synthesis in bacteria". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 42 (12): 3251–5. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 9835522. PMC 106030. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/content/full/42/12/3251.

- ↑ Colca JR, McDonald WG, Waldon DJ, et al. (June 2003). "Cross-linking in the living cell locates the site of action of oxazolidinone antibiotics". Journal of Biological Chemistry 278 (24): 21972–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M302109200. ISSN 0021-9258. PMID 12690106. http://www.jbc.org/cgi/content/full/278/24/21972.

- ↑ Ippolito JA, Kanyo ZF, Wang D, et al. (June 2008). "Crystal structure of the oxazolidinone antibiotic linezolid bound to the 50S ribosomal subunit". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 51 (12): 3353–6. doi:10.1021/jm800379d. ISSN 0022-2623. PMID 18494460.

- ↑ Wilson DN, Schluenzen F, Harms JM, Starosta AL, Connell SR, Fucini P (September 2008). "The oxazolidinone antibiotics perturb the ribosomal peptidyl-transferase center and effect tRNA positioning" (Free full text). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 105 (36): 13339–44. doi:10.1073/pnas.0804276105. ISSN 0027-8424. PMID 18757750. PMC 2533191. http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18757750.

- ↑ Tsiodras S, Gold HS, Sakoulas G, et al. (July 2001). "Linezolid resistance in a clinical isolate of Staphylococcus aureus". The Lancet 358 (9277): 207–8. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)05410-1. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 11476839.

- ↑ Jones RN, Kohno S, Ono Y, Ross JE, Yanagihara K (June 2009). "ZAAPS International Surveillance Program (2007) for linezolid resistance: results from 5591 Gram-positive clinical isolates in 23 countries". Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 64 (2): 191–201. doi:10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2009.03.001. ISSN 0732-8893. PMID 19500528.

- ↑ Hope R, Livermore DM, Brick G, Lillie M, Reynolds R (November 2008). "Non-susceptibility trends among staphylococci from bacteraemias in the UK and Ireland, 2001-06". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 62 (Suppl 2): ii65–74. doi:10.1093/jac/dkn353. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 18819981. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/62/suppl_2/ii65.

- ↑ Auckland C, Teare L, Cooke F, et al. (November 2002). "Linezolid-resistant enterococci: report of the first isolates in the United Kingdom". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 50 (5): 743–6. doi:10.1093/jac/dkf246. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 12407134. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/content/full/50/5/743.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 Scheetz MH, Knechtel SA, Malczynski M, Postelnick MJ, Qi C (June 2008). "Increasing incidence of linezolid-intermediate or -resistant, vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium strains parallels increasing linezolid consumption" (Free full text). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 52 (6): 2256–9. doi:10.1128/AAC.00070-08. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 18391028. PMC 2415807. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18391028.

- ↑ Schumacher A, Trittler R, Bohnert JA, Kümmerer K, Pagès JM, Kern WV (June 2007). "Intracellular accumulation of linezolid in Escherichia coli, Citrobacter freundii and Enterobacter aerogenes: role of enhanced efflux pump activity and inactivation" (Free full text). Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 59 (6): 1261–4. doi:10.1093/jac/dkl380. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 16971414. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16971414.

- ↑ Saager B, Rohde H, Timmerbeil BS, et al. (September 2008). "Molecular characterisation of linezolid resistance in two vancomycin-resistant (VanB) Enterococcus faecium isolates using Pyrosequencing". European Journal of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases 27 (9): 873–8. doi:10.1007/s10096-008-0514-6. ISSN 0934-9723. PMID 18421487.

- ↑ Besier S, Ludwig A, Zander J, Brade V, Wichelhaus TA (April 2008). "Linezolid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus: gene dosage effect, stability, fitness costs, and cross-resistances" (Free full text). Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 52 (4): 1570–2. doi:10.1128/AAC.01098-07. ISSN 0066-4804. PMID 18212098. PMC 2292563. http://aac.asm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=18212098.

- ↑ Feng J, Lupien A, Gingras H, et al. (May 2009). "Genome sequencing of linezolid-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae mutants reveals novel mechanisms of resistance". Genome Research 19 (7): 1214–23. doi:10.1101/gr.089342.108. ISSN 1088-9051. PMID 19351617.

- ↑ Lincopan N, de Almeida LM, Elmor de Araújo MR, Mamizuka EM (April 2009). "Linezolid resistance in Staphylococcus epidermidis associated with a G2603T mutation in the 23S rRNA gene". International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents 34 (3): 281–2. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.02.023. ISSN 0924-8579. PMID 19376688.

- ↑ Liakopoulos A, Neocleous C, Klapsa D, et al. (July 2009). "A T2504A mutation in the 23S rRNA gene responsible for high-level resistance to linezolid of Staphylococcus epidermidis". Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 64 (1): 206–7. doi:10.1093/jac/dkp167. ISSN 0305-7453. PMID 19429927.

- ↑ Lawrence KR, Adra M, Gillman PK (June 2006). "Serotonin toxicity associated with the use of linezolid: a review of postmarketing data". Clinical Infectious Diseases 42 (11): 1578–83. doi:10.1086/503839. ISSN 1058-4838. PMID 16652315.

- ↑ Huang V, Gortney JS (December 2006). "Risk of serotonin syndrome with concomitant administration of linezolid and serotonin agonists". Pharmacotherapy 26 (12): 1784–93. doi:10.1592/phco.26.12.1784. ISSN 0277-0008. PMID 17125439.

- ↑ Waknine, Yael (September 5, 2008). "FDA Safety Changes: Mirena, Zyvox, Orencia". Medscape. http://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/580101. Retrieved 2008-09-06. Freely available with registration.

- ↑ Stalker DJ, Jungbluth GL (2003). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of linezolid, a novel oxazolidinone antibacterial". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 42 (13): 1129–40. doi:10.2165/00003088-200342130-00004. ISSN 0312-5963. PMID 14531724.

- ↑ "Pfizer agrees record fraud fine". BBC News. September 2, 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/8234533.stm. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

- ↑ Harris, Gardiner (September 2, 2009). "Pfizer pays $2.3 billion to settle marketing case". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/03/business/03health.html. Retrieved 2009-09-12.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||