Yukio Mishima

| 三島 由紀夫 Yukio Mishima |

|

|---|---|

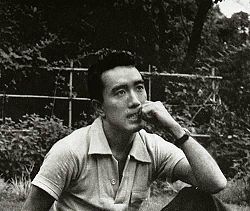

photograph by Shirou Aoyama (1956) |

|

| Born | January 14, 1925 Shinjuku, Tokyo |

| Died | November 25, 1970 (aged 45) JSDF headquarters, Tokyo |

| Pen name | Yukio Mishima |

| Occupation | novelist, playwright, poet, short story writer, essayist |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Ethnicity | Japanese |

| Citizenship | Japanese |

| Alma mater | University of Tokyo |

| Period | 1944–1970 |

| Children | Noriko Tomita (Daughter), Iichiro Hiraoka (Son) |

|

Influences

Ōshio Heihachirō[1], Thomas Mann[1], Friedrich Nietzsche[1], Raymond Radiguet[2], François Mauriac[2], Consciousness-only Buddhism

|

|

Yukio Mishima (三島 由紀夫 Mishima Yukio) was the pen name of Kimitake Hiraoka (平岡 公威 Hiraoka Kimitake, January 14, 1925 – November 25, 1970), a Japanese author, poet and playwright, also remembered for his ritual suicide by seppuku. Nominated three times for the Nobel Prize in Literature, Mishima is considered one of the most important Japanese authors of the 20th century, whose avant-garde work displayed a blending of modern and traditional aesthetics that broke cultural boundaries, with a focus on homosexuality, death, and political change.[3]

Contents |

Early life

Mishima was born in the Yotsuya district of Tokyo (now part of Shinjuku). His father was Azusa Hiraoka, a government official, and his mother, Shizue, was the daughter of a school principal in Tokyo. His paternal grandparents were Jotarō and Natsuko Hiraoka. He had a younger sister named Mitsuko, who died of typhus, and a younger brother named Chiyuki.

Mishima's early childhood was dominated by the shadow of his grandmother, Natsu, who took the boy and separated him from his immediate family for several years.[4] Natsu was the illegitimate granddaughter of Matsudaira Yoritaka, the daimyo of Shishido in Hitachi Province, and had been raised in the household of Prince Arisugawa Taruhito; she maintained considerable aristocratic pretensions even after marrying Mishima's grandfather, a bureaucrat who had made his fortune in the newly opened colonial frontier and who rose to become Governor-General of Karafuto. She was also prone to violence and morbid outbursts, which are occasionally alluded to in Mishima's works.[5] It is to Natsu that some biographers have traced Mishima's fascination with death.[6] Natsu did not allow Mishima to venture into the sunlight, to engage in any kind of sport or to play with other boys; he spent much of his time alone or with female cousins and their dolls.[5]

Mishima returned to his immediate family at 12. His father, a man with a taste for military discipline, employed such tactics as holding the young boy up to the side of a speeding train; he also raided Mishima's room for evidence of an "effeminate" interest in literature and often ripped up the boy's manuscripts.

Schooling and early works

At age six, Mishima enrolled in elite Peers School (Gakushuin 学習院).[7] At 12, Mishima began to write his first stories. He read voraciously the works of Oscar Wilde, Rainer Maria Rilke and numerous classic Japanese authors. After six years at school, he became the youngest member of the editorial board in its literary society. Mishima was attracted to the works of Tachihara Michizō, which in turn created an appreciation for the classical form of the waka. Mishima's first published works included waka poetry, before he turned his attention to prose.

He was invited to write a prose short story for the Peers' School literary magazine and submitted Hanazakari no Mori (花ざかりの森 The Forest in Full Bloom), a story in which the narrator describes the feeling that his ancestors somehow still live within him. Mishima’s teachers were so impressed with the work that they recommended it for the prestigious literary magazine, Bungei-Bunka (文芸文化 Literary Culture). The story, which makes use of the metaphors and aphorisms which later became his trademarks, was published in book form in 1944, albeit in a limited fashion (4,000 copies) because of the wartime shortage of paper. In order to protect him from a possible backlash from his schoolmates, his teachers coined the pen-name "Yukio Mishima".

Mishima's story Tabako (煙草 The Cigarette), published in 1946, describes some of the scorn and bullying he faced at school when he later confessed to members of the school's rugby union club that he belonged to the literary society. This trauma also provided material for the later story Shi o Kaku Shōnen (詩を書く少年 The Boy Who Wrote Poetry) in 1954.

Mishima received a draft notice for the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. At the time of his medical check up, he had a cold and spontaneously lied to the army doctor about having symptoms of tuberculosis and thus was declared unfit for service.

Although his father had forbidden him to write any further stories, Mishima continued to write secretly every night, supported and protected by his mother, who was always the first to read a new story. Attending lectures during the day and writing at night, Mishima graduated from the University of Tokyo in 1947. He obtained a position as an official in the government's Finance Ministry and was set up for a promising career.

However, Mishima had exhausted himself so much that his father agreed to his resigning from his position during his first year in order to devote his time to writing.

Post-war literature

Mishima was a disciplined and versatile writer. He wrote not only novels, popular serial novellas, short stories and literary essays, but also highly acclaimed plays for the Kabuki theater and modern versions of traditional Noh drama.

Mishima began the short story Misaki nite no Monogatari (岬にての物語 A Story at the Cape) in 1945, and continued to work on it through the end of World War II. In January 1946, he visited famed writer Yasunari Kawabata in Kamakura, taking with him the manuscripts for Chūsei (中世 The Middle Ages) and Tabako, and asking for Kawabata’s advice and assistance. In June 1946, per Kawabata's recommendations, Tabako was published in the new literary magazine Ningen (人間 Humanity).

Also in 1946, Mishima began his first novel, Tōzoku (盗賊 Thieves), a story about two young members of the aristocracy drawn towards suicide. It was published in 1948, placing Mishima in the ranks of the Second Generation of Postwar Writers. He followed with Confessions of a Mask, a semi-autobiographical account of a young latent homosexual who must hide behind a mask in order to fit into society. The novel was extremely successful and made Mishima a celebrity at the age of 24. Around 1949, Mishima published a series of essays in Kindai Bungaku on Yasunari Kawabata, for whom he had always had a deep appreciation.

His writing gained him international celebrity and a sizable following in Europe and America, as many of his most famous works were translated into English. Mishima traveled extensively; in 1952 he visited Greece, which had fascinated him since childhood. Elements from his visit appear in Shiosai (潮騒 Sound of the Waves), which was published in 1954, and which drew inspiration from the Greek legend of Daphnis and Chloe.

Mishima made use of contemporary events in many of his works. The Temple of the Golden Pavilion in 1956 is a fictionalization of the burning of the famous temple in Kyoto. Utage no Ato (After the Banquet), published in 1960, so closely followed the events surrounding politician Hachirō Arita's campaign to become governor of Tokyo that Mishima was sued for invasion of privacy. In 1962, Mishima's most avant-garde work, Utsukushii Hoshi (Beautiful Star), which at times comes close to science fiction, was published to mixed critical response.

Mishima was among those considered for the Nobel Prize for Literature three times and was the darling of many foreign publications. However, in 1968 his early mentor Kawabata won the Nobel Prize and Mishima realized that the chances of it being given to another Japanese author in the near future were slim. It is also believed that Mishima wanted to leave the prize to the aging Kawabata, out of respect for the man who had first introduced him to the literary circles of Tokyo in the 1940s.

Acting

Mishima was also an actor, and he had a starring role in Yasuzo Masumura's 1960 film, Afraid to Die. He also has had roles in films including Yukoku (1966), Black Lizard (1968) and Hitokiri (1969). He also sang the theme song for Hitokiri.

Private life

In 1955, Mishima took up weight training and his workout regimen of three sessions per week was not disrupted for the final 15 years of his life. In his 1968 essay Sun and Steel, Mishima deplored the emphasis given by intellectuals to the mind over the body. Mishima later also became very skillful at kendō.

Although he visited gay bars in Japan, Mishima's sexual orientation remains a matter of debate, though his widow wanted that part of his life downplayed after his death.[8] However, several people have claimed to have had homosexual relationships with Mishima, including writer Jiro Fukushima who, in his book, published a revealing correspondence between himself and the famed novelist. Soon after publication, Mishima's children successfully sued Fukushima for violating Mishima's privacy.[9] After briefly considering a marital alliance with Michiko Shōda—she later became the wife of Emperor Akihito—he married Yoko Sugiyama on June 11, 1958. The couple had two children, a daughter named Noriko (born June 2, 1959) and a son named Ichiro (born May 2, 1962).

In 1967, Mishima enlisted in the Ground Self Defense Force (GSDF) and underwent basic training. A year later, he formed the Tatenokai (Shield Society), a private army composed primarily of young students who studied martial principles and physical discipline, and swore to protect the Emperor. Mishima trained them himself. However, under Mishima's ideology, the emperor was not necessarily the reigning Emperor, but rather the abstract essence of Japan. In Eirei no Koe (Voices of the Heroic Dead), Mishima actually denounces Emperor Hirohito for renouncing his claim of divinity at the end of World War II.

In the last 10 years of his life, Mishima wrote several full length plays, acted in several movies and co-directed an adaptation of one of his stories, Patriotism, the Rite of Love and Death. He also continued work on his final tetralogy, Hōjō no Umi (Sea of Fertility), which appeared in monthly serialized format starting in September 1965.

Coup attempt and suicide

On November 25, 1970, Mishima and four members of the Tatenokai, under pretext, visited the commandant of the Ichigaya Camp—the Tokyo headquarters of the Eastern Command of Japan's Self-Defense Forces.[8] Inside, they barricaded the office and tied the commandant to his chair. With a prepared manifesto and banner listing their demands, Mishima stepped onto the balcony to address the soldiers gathered below. His speech was intended to inspire a coup d'etat restoring the powers of the emperor. He succeeded only in irritating them, however, and was mocked and jeered. He finished his planned speech after a few minutes, returned to the commandant's office and committed seppuku. The customary kaishakunin duty at the end of this ritual had been assigned to Tatenokai member Masakatsu Morita, but Morita was unable to properly perform the task: after several attempts, he allowed another Tatenokai member, Hiroyasu Koga, to behead Mishima.

Another traditional element of the suicide ritual was the composition of jisei no ku (death poems) before their entry into the headquarters.[10] Mishima planned his suicide meticulously for at least a year and no one outside the group of hand-picked Tatenokai members had any indication of what he was planning. His biographer, translator and former friend John Nathan suggests that the coup attempt was only a pretext for the ritual suicide of which Mishima had long dreamed.[11] Mishima made sure his affairs were in order and left money for the legal defense of the three surviving Tatenokai members.

Aftermath

Much speculation has surrounded Mishima's suicide. At the time of his death he had just completed the final book in his The Sea of Fertility tetralogy.[8] He was recognized as one of the most important post-war stylists of the Japanese language.

Mishima wrote 40 novels, 18 plays, 20 books of short stories, and at least 20 books of essays, one libretto, as well as one film. A large portion of this oeuvre comprises books written quickly for profit, but even if these are disregarded, a substantial body of work remains.

Politics

Mishima espoused a very individual brand of nationalism towards the end of his life. He was hated by leftists, in particular for his outspoken and anachronistic commitment to bushidō (the code of the samurai) and by mainstream nationalists for his contention, in Bunka Bōeiron (文化防衛論 A Defense of Culture), that Hirohito should have abdicated and taken responsibility for the war dead.

Awards

- Shincho Prize from Shinchosha Publishing, 1954, for The Sound of Waves.

- Kishida Prize for Drama from Shinchosha Publishing, 1955.

- Yomiuri Prize from Yomiuri Newspaper Co., for best novel, 1957, The Temple of the Golden Pavilion.

- Yomiuri Prize from Yomiuri Newspaper Co., for best drama, 1961, Toka no Kiku.

Major works

| Japanese Title | English Title | Year | English translation, year | ISBN |

| 假面の告白 Kamen no Kokuhaku |

Confessions of a Mask | 1948 | Meredith Weatherby, 1958 | ISBN 0-8112-0118-X |

| 愛の渇き Ai no Kawaki |

Thirst for Love | 1950 | Alfred H. Marks, 1969 | ISBN 4-10-105003-1 |

| 禁色 Kinjiki |

Forbidden Colors | 1953 | Alfred H. Marks, 1968–1974 | ISBN 0-375-70516-3 |

| 潮騷 Shiosai |

The Sound of Waves | 1954 | Meredith Weatherby, 1956 | ISBN 0-679-75268-4 |

| 金閣寺 Kinkaku-ji* |

The Temple of the Golden Pavilion | 1956 | Ivan Morris, 1959 | ISBN 0-679-75270-6 |

| 鏡子の家 Kyōko no Ie |

Kyoko's House | 1959 | ISBN | |

| 宴のあと Utage no Ato |

After the Banquet | 1960 | Donald Keene, 1963 | ISBN 0-399-50486-9 |

| 午後の曳航 Gogo no Eikō |

The Sailor Who Fell from Grace with the Sea | 1963 | John Nathan, 1965 | ISBN 0-679-75015-0 |

| 絹と明察 Kinu to Meisatsu |

Silk and Insight | 1964 | Hiroaki Sato, 1998 | ISBN 0-7656-0299-7 |

| 三熊野詣 Mikumano Mōde (short story) |

Acts of Worship | 1965 | John Bester, 1995 | ISBN 0-87011-824-2 |

| サド侯爵夫人 Sado Kōshaku Fujin (play) |

Madame de Sade | 1965 | Donald Keene, 1967 | ISBN 0-394-17304-X |

| 憂國 Yūkoku (short story) |

Patriotism | 1966 | Geoffrey W. Sargent, 1966 | ISBN 0-8112-1312-9 |

| 真夏の死 Manatsu no Shi |

Death in Midsummer and other stories | 1966 | Edward G. Seidensticker, Ivan Morris, Donald Keene, Geoffrey W. Sargent, 1966 |

ISBN 0-8112-0117-1 |

| 葉隠入門 Hagakure Nyūmon |

Way of the Samurai | 1967 | Kathryn Sparling, 1977 | ISBN 0-465-09089-3 |

| わが友ヒットラー Waga Tomo Hittorā (play) |

My Friend Hitler and Other Plays | 1968 | Hiroaki Sato, 2002 | ISBN 0-231-12633-6 |

| 太陽と鐡 Taiyō to Tetsu |

Sun and Steel | 1970 | John Bester | ISBN 4-7700-2903-9 |

| 豐饒の海 Hōjō no Umi |

The Sea of Fertility tetralogy: | 1964- 1970 |

ISBN 0-677-14960-3 | |

| I. 春の雪 Haru no Yuki |

1. Spring Snow | 1968 | Michael Gallagher, 1972 | ISBN 0-394-44239-3 |

| II. 奔馬 Honba |

2. Runaway Horses | 1969 | Michael Gallagher, 1973 | ISBN 0-394-46618-7 |

| III. 曉の寺 Akatsuki no Tera |

3. The Temple of Dawn | 1970 | E. Dale Saunders and Cecilia S. Seigle, 1973 | ISBN 0-394-46614-4 |

| IV. 天人五衰 Tennin Gosui |

4. The Decay of the Angel | 1970 | Edward Seidensticker, 1974 | ISBN 0-394-46613-6 |

*For the temple called Kinkaku-ji, see Kinkaku-ji.

Plays for classical Japanese theatre

In addition to contemporary-style plays such as Madame de Sade, Mishima wrote for two of the three genres of classical Japanese theatre: Noh and Kabuki (as a proud Tokyoite, he would not even attend the Bunraku puppet theatre, always associated with Osaka and the provinces).[12]

Though Mishima took themes, titles and characters from the Noh canon, his twists and modern settings, such as hospitals and ballrooms, startled audiences accustomed to the long-settled originals.

Donald Keene translated Five Modern Noh Plays (Tuttle, 1981; ISBN 0-8048-1380-9). Most others remain untranslated and so lack an "official" English title; in such cases it is therefore preferable to use the rōmaji title.

| Year | Japanese Title | English Title | Genre |

| 1950 | 邯鄲 Kantan |

Noh | |

| 1952 | 卒塔婆小町 Sotoba Komachi |

Komachi at the Stupa (gravepost) | Noh |

| 1954 | 鰯賣戀曳網 Iwashi Uri Koi Hikiami |

The Sardine Seller's Net of Love | Kabuki |

| 1955 | 綾の鼓 Aya no Tsuzumi |

The Damask Drum | Noh |

| 1955 | 芙蓉露大内実記 Fuyō no Tsuyu Ōuchi Jikki |

The Ōuchi Clan (oversimplified/not standardised) | Kabuki |

| 1956 | 班女 Hanjo |

Noh | |

| 1956 | 葵の上 Aoi no Ue |

The Lady Aoi | Noh |

| 1965 | 弱法師 Yoroboshi |

The Blind Young Man | Noh |

| 1969 | 椿説弓張月 Chinsetsu Yumiharizuki |

The Crescent, or Crescent Moon: The Adventures of Tametomo, literally "The Strange Theory of a Paper Lantern's Appearance" | Kabuki |

Films

| Year | Title | USA Release Title(s) | Character | Director |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 純白の夜 Jumpaku no Yoru |

Unreleased in the U.S. | Hideo Ōba | |

| 1959 | 不道徳教育講座 Fudōtoku Kyōikukōza |

Unreleased in the U.S. | himself | Katsumi Nishikawa |

| 1960 | からっ風野郎 Karakkaze Yarō |

Afraid to Die | Takeo Asahina | Yasuzo Masumura |

| 1966 | 憂国 Yūkoku |

The Rite of Love and Death Patriotism |

Shinji Takeyama | Domoto Masaki, Yukio Mishima |

| 1968 | 黒蜥蝪 Kurotokage |

Black Lizard | Human Statue | Kinji Fukasaku |

| 1969 | 人斬り Hitokiri |

Tenchu! | Shimbei Tanaka | Hideo Gosha |

| 1985 | Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters |

Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters | Paul Schrader Music by Philip Glass |

|

| The Strange Case of Yukio Mishima (BBC documentary) |

The Strange Case of Yukio Mishima | Michael Macintyre |

Photo modeling

Mishima has been featured as a photo model in Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses by Eikoh Hosoe, as well as in Young Samurai: Bodybuilders of Japan and OTOKO: Photo Studies of the Young Japanese Male by Tamotsu Yatō. Donald Richie gives a short lively account[13] of Mishima, dressed in a loincloth and armed with a sword, posing in the snow for one of Tamotsu Yato's photoshoots.

Works about Mishima

- Ba-ra-kei: Ordeal by Roses by Eikō Hosoe and Mishima (photoerotic collection of images of Mishima, with his own commentary) (Aperture 2002 ISBN 0-89381-169-6)

- Deadly Dialectics: Sex, Violence, and Nihilism in the World of Yukio Mishima by Roy Starrs (University of Hawaii Press, 1994, ISBN 0-8248-1630-7 and ISBN 0-8248-1630-7)

- Escape from the Wasteland: Romanticism and Realism in the Fiction of Mishima Yukio and Oe Kenzaburo (Harvard-Yenching Institute Monograph Series, No 33) by Susan J. Napier (Harvard University Press, 1995 ISBN 0-674-26181-X)

- Mishima: A Biography by John Nathan (Boston, Little, Brown and Company 1974, ISBN 0-316-59844-5)

- Mishima ou la vision du vide (Mishima : A Vision of the Void), essay by Marguerite Yourcenar trans. by Alberto Manguel 2001 ISBN 0-226-96532-5)

- Rogue Messiahs: Tales of Self-Proclaimed Saviors by Colin Wilson (Mishima profiled in context of phenomenon of various "outsider" Messiah types), (Hampton Roads Publishing Company 2000 ISBN 1-57174-175-5)

- The Life and Death of Yukio Mishima, by Henry Scott Stokes London : Owen, 1975 ISBN 0-7206-0123-1)

- The Madness and Perversion of Yukio Mishima by Jerry S. Piven. (Westport, Connecticut, Praeger Publishers, 2004 ISBN 0-275-97985-7)

- Teito Monogatari {vol. 5–10) by Hiroshi Aramata (a fantasy/historical novel featuring Mishima as a central character contending with malignant spiritual forces which feed off his nationalist pride), (Kadokawa Shoten ISBN/ASIN 4041690056)

- Yukio Mishima by Peter Wolfe ("reviews Mishima's life and times, discusses, his major works, and looks at important themes in his novels," 1989, ISBN 0-8264-0443-X)

- Yukio Mishima, Terror and Postmodern Japan by Richard Appignanesi (2002, ISBN 1-84046-371-6)

- Mishima's Sword–Travels in Search of a Samurai Legend by Christopher Ross (2006, ISBN 0-00-713508-4)

- Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters (1985), a film directed by Paul Schrader

- Yukio Mishima: Samurai Writer, a BBC documentary on Yukio Mishima, directed by Michael Macintyre, (1985, VHS ISBN 978-1-4213-6981-5, DVD ISBN 978-1-4213-6982-2)

- Yukio Mishima, a play by Adam Darius and Kazimir Kolesnik, first performed at Holloway Prison, London, in 1991, and later in Finland, Slovenia and Portugal.

- String Quartet No.3, "Mishima", by Philip Glass. A compilation of his soundtrack for Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters it has a duration of 18 minutes.

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Waagenar, Dick, and Iwamoto, Yoshio (1975). "Yukio Mishima: Dialectics of Mind and Body". Contemporary Literature, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Winter, 1975), pp. 41-60

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Yamanouchi,Hisaaki (1972). "Mishima Yukio and his Suicide". Modern Asian Studies, Vol. 6, No. 1 (1972), pp. 1-16

- ↑ http://www.enotes.com/twentieth-century-criticism/mishima-yukio

- ↑ Profile of Yukio Mishima (1925–1970)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 glbtq Entry Mishima, Yukio (1925-1970). Retrieved on 2007-2-6.

- ↑ Profile Yukio Mishima (January 14, 1925 - November 25, 1970. 2007 February 2–6.

- ↑ "Guide to Yamanakako Forest Park of Literature( Mishima Yukio Literary Museum)". http://www.mishimayukio.jp/history.html. Retrieved 20 October 2009. "三島由紀夫の年譜". http://www.mishimayukio.jp/history.html. Retrieved 20 October 2009.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Mishima: Film Examines an Affair with Death by Michiko Kakutani. New York Times. September 15, 1985.

- ↑ Sato, Hiroaki (2008-12-29). "Suppressing more than free speech". The View from New York (The Japan Times). http://search.japantimes.co.jp/rss/eo20081229hs.html. Retrieved 2009-01-10.

- ↑ Donald Keene, The Pleasures of Japanese Literature, p.62

- ↑ Nathan, John. Mishima: A biography, Little Brown and Company: Boston/Toronto, 1974.

- ↑ Donald Keene, Chronicles of My Life: An American in the Heart of Japan, Columbia University Press, 2008. ISBN 0231513488 Cf. Chapter 29 on Mishima in New York

- ↑ Donald Richie, The Japan Journals: 1947-2004, Stone Bridge Press (2005), pp. 148–149.

External links

- The Mishima Yukio Cyber Museum In Japanese only

- Web page devoted to Yukio Mishima Page with some information about Mishima, but with pop-up windows and advertisements

- Yukio Mishima: A 20th Century Samurai

- Books and Writers bio

- Short bio with photo

- Mishima chronology, with links

- YUKIO MISHIMA: The Harmony of Pen and Sword Ceremony commemorating his 70th Birthday Anniversary

- Blood and Flowers: Purity of Action in The Sea of Fertility

- Film review of Yukoku (Patriotism)

- Mishima is interviewed in English on a range of subjects From a 1980s BBC documentary (9:02)

- Mishima is interviewed in English on the subject of Japanese Nationalism From Canadian Television (3:59)

- Headlessgod.com: An Online Tribute to Yukio Mishima (Mishima-related news, quotes, links)