North American X-15

| X-15 | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Role | Experimental high-speed rocket-powered research aircraft |

| Manufacturer | North American Aviation |

| First flight | 8 June 1959 |

| Introduced | 17 September 1959 |

| Retired | December 1970 |

| Primary users | United States Air Force NASA |

| Number built | 3 |

The North American X-15 rocket-powered aircraft/spaceplane was part of the X-series of experimental aircraft, initiated with the Bell X-1, that were made for the USAF, NASA, and the USN. The X-15 set speed and altitude records in the early 1960s, reaching the edge of outer space and returning with valuable data used in aircraft and spacecraft design. It currently holds the official world record for the fastest speed ever reached by a manned rocket powered aircraft.[1]

During the X-15 program, 13 of the flights (by eight pilots) met the USAF spaceflight criteria by exceeding the altitude of 50 miles (80.47 km, 264,000 ft), thus qualifying the pilots for astronaut status. The USAF pilots qualified for USAF astronaut wings, while the civilian pilots were later awarded NASA astronaut wings.[2][3]

Of all the X-15 missions, two flights (by the same pilot) qualified as space flights per the international (Fédération Aéronautique Internationale) definition of a spaceflight by exceeding a 100 kilometer (62.137 mi, 328,084 ft) altitude.

Contents |

Design and development

The X-15 was based on a concept study from Walter Dornberger for the NACA for a hypersonic research aircraft.[4] The requests for proposal were published on 30 December 1954 for the airframe and on 4 February 1955 for the rocket engine. The X-15 was built by two manufacturers: North American Aviation was contracted for the airframe in November 1955, and Reaction Motors was contracted for building the engines in 1956.

Like most X-series aircraft, the X-15 was designed to be carried aloft, under the wing of a B-52 bomber plane. The X-15 fuselage was long and cylindrical, with rear fairings that flattened its appearance, and thick, dorsal and ventral wedge-fin stabilizers. Parts of the fuselage were heat-resistant nickel alloy (Inconel-X 750).[4] The retractable landing gear comprised a nose-wheel carriage and two rear skis. The skis did not extend beyond the ventral fin, which required the pilot to jettison the lower fin (fitted with a parachute) just before landing. The two XLR-11 rocket engines for the initial X-15A model delivered 16,000 lbf (71 kN) maximum thrust each, for a total of 32,000 pounds-force. The main engine (installed later) was a single XLR-99 rocket engine delivering 57,000 lbf (250 kN) at sea level, and 70,000 lbf (310 kN) at peak altitude. The idle thrust of the XLR-99 was 15,000 lbf (67 kN).

Engines and fuel

Early flights used two Reaction Motors XLR11 engines. Later flights were undertaken with a single Reaction Motors Inc XLR99 rocket engine generating 57,000 pounds-force (250 kN) of thrust powered the aircraft. This engine used ammonia and liquid oxygen for propellant and hydrogen peroxide to drive the high-speed turbopump that delivered fuel to the engine. The XLR99 could be throttled, and were the first such controllable engines that were "man-rated", that is, declared safe to operate with a human aboard.

Operational history

Three X-15s were built, flying 199 test flights, the last on 24 October 1968. The first X-15 flight was an unpowered test flight by Scott Crossfield, on 8 June 1959; he also piloted the first powered flight, on 17 September 1959, with his first XLR-99 flight on 15 November 1960. Twelve test pilots flew the X-15; among them were Neil Armstrong (first man on the moon) and Joe Engle (a space shuttle commander). In July and August 1963, pilot Joe Walker crossed the 100 km altitude mark, joining the NASA astronauts and Soviet Cosmonauts as the only men to have crossed the barrier into outer space (Soviet Yuri Gagarin was the first man in space, reaching 327 km in apogee of his orbital flight, while Alan Shepard was the first American in space, reaching 187 km during suborbital flight) and becoming the first to exceed this threshold twice.

U.S. Air Force test pilot Major Michael J. Adams was killed on 15 November 1967 in X-15 Flight 191 when his craft (X-15-3) entered a hypersonic spin while descending, then oscillated violently as aerodynamic forces increased after re-entry. As his craft's flight control system operated the control surfaces to their limits, the craft's acceleration built to 15 g vertical and 8 g lateral. The airframe broke apart at 60,000 ft altitude, scattering the craft's wreckage for 50 square miles. On 8 June 2004, a monument was erected at the cockpit's locale, near Randsburg, California.[5] Major Adams was posthumously awarded Air Force astronaut wings for his final flight in craft X-15-3, which had reached 266,000 ft (81.1 km, 50.4 mi.) of altitude. In 1991, his name was added to the Astronaut Memorial.

The second X-15A was rebuilt after a landing accident. It was lengthened 2.4 feet (0.73 m), a pair of auxiliary fuel tanks attached under the fuselage, and a heat-resistant surface treatment applied. Re-named the X-15A-2, it first flew on 28 June 1964, reaching 7,274 km/h (4,520 mph, 2,021 m/s).

The altitudes attained by the X-15 aircraft do not match that of Alan Shephard's 1961 NASA space capsule flight nor subsequent NASA space capsules and space shuttle flights. However, the X-15 flights did reign supreme among rocket-powered aircraft until the second spaceflight of Space Ship One in 2004.

Five aircraft were the X-15 program: three X-15s, two B-52 bombers:

- X-15A-1 - 56-6670, 82 powered flights

- X-15A-2 - 56-6671, 53 powered flights

- X-15A-3 - 56-6672, 64 powered flights

- NB-52A - 52-003 (retired in October 1969)

- NB-52B - 52-008 (retired in November 2004)

A 200th flight over Nevada was slated for 21 November 1968, piloted by William J. Knight. Technical problems and bad weather delayed the flight six times, and on 20 December 1968, the 200th flight was finally cancelled. The X-15 was unfastened from the wing of bomber NB-52A, and prepared for indefinite storage.

Gallery

X-15A-2 on the flight line |

Neil Armstrong with X-15 ship #1 (56-6670)01/01/1960 |

X-15 on Boeing B-52 Mothership wing pylon |

X-15 in full scale ablative coating |

X-15 on display at the National Air and Space Museum |

X-15 nose |

Current static displays

- X-15-1 (s/n 56-6670) is on display in the National Air and Space Museum "Milestones of Flight" gallery, Washington, D.C.

- X-15-2A (s/n 56-6671) is at the National Museum of the United States Air Force, at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, near Dayton, Ohio. It was retired to the Museum in October 1969.[6] The aircraft is displayed in the Museum's Research & Development Hangar alongside other "X-planes", including the Bell X-1 and X-3 Stiletto.

- X-15-3 (s/n 56-6672) was destroyed. Parts have been recovered at the crash site as late as the 1990s.

Mock-ups:

- Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards AFB, California, USA (painted with s/n 56-6672)

- Pima Air Museum, Tucson, Arizona (painted with s/n 56-6671)

- Evergreen Aviation Museum, McMinnville, Oregon (painted with s/n 56-6671). This is the only known full-scale wooden mock-up of the X-15, and it is displayed along with one of the rocket motors.

Stratofortress Motherships:

- NB-52A (s/n 52-003) is at the Pima Air and Space Museum, Tucson, Arizona - launched the X-15 #1 thirty times, the X-15#2 eleven times, and the X-15#3 thirty-one times (as well as the M2-F2 four times, the HL-10 eleven times and the X-24A twice).

- NB-52B (s/n 52-008) is at the Dryden Flight Research Center, Edwards AFB, California, USA - Launched the majority of X-15 flights.

Aftermath

Before 1958, USAF and NACA, (later NASA), officials discussed an orbital X-15 spacecraft — the X-15B — for launching to outer space atop an SM-64 Navajo missile, that was cancelled when the NACA became the NASA, and Project Mercury was approved. By 1959, the X-20 Dyna-Soar space-glider program became the USAF's preferred means for launching military manned-spacecraft into orbit; the program was cancelled in the early 1960s.

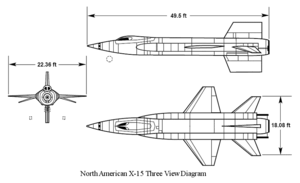

Specifications (X-15)

General characteristics

- Crew: one

- Length: 50 ft 9 in (15.45 m)

- Wingspan: 22 ft 4 in (6.8 m)

- Height: 13 ft 6 in (4.12 m)

- Wing area: 200 ft² (18.6 m²)

- Empty weight: 14,600 lb (6,620 kg)

- Loaded weight: 34,000 lb (15,420 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 34,000 lb (15,420 kg)

- Powerplant: 1× Thiokol XLR99-RM-2 liquid-fuel rocket engine, 70,400 lbf at 30 km (313 kN)

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 6.72 (4,520 mph / 7,274 km/h)

- Range: 280 mi (450 km)

- Service ceiling: 67 mi (354,330 ft / 108 km)

- Rate of climb: 60,000 ft/min (18,288 m/min)

- Wing loading: 170 lb/ft² (829 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 2.07

Record flights

Highest flights

There are two definitions of how high a person must go to be referred to as an astronaut. The USAF decided to award astronaut wings to anyone who achieved an altitude of 50 miles (80.47 km) or more. However the FAI set the limit of space at 100 km. Thirteen X-15 flights went higher than 50 miles (80.47 km) and two of these reached over 62.137 miles (100 km).

| Flight | Date | Top speed | Altitude | Pilot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flight 62 | 17 July 1962 | 3,831 mph (6,165 km/h) | 59.6 miles (95.9 km) | Robert M. White |

| Flight 77 | 17 January 1963 | 3,677 mph (5,918 km/h) | 51.4 miles (82.7 km) | Joe Walker |

| Flight 87 | 27 June 1963 | 3,425 mph (5,512 km/h) | 53.9 miles (86.7 km) | Robert Rushworth |

| Flight 90 | 19 July 1963 | 3,710 mph (5,970 km/h) | 65.8 miles (105.9 km) | Joe Walker |

| Flight 91 | 22 August 1963 | 3,794 mph (6,106 km/h) | 67.0 miles (107.8 km) | Joe Walker |

| Flight 138 | 29 June 1965 | 3,431 mph (5,522 km/h) | 53.1 miles (85.5 km) | Joseph H. Engle |

| Flight 143 | 10 August 1965 | 3,549 mph (5,712 km/h) | 51.3 miles (82.6 km) | Joseph H. Engle |

| Flight 150 | 28 September 1965 | 3,731 mph (6,004 km/h) | 55.9 miles (90.0 km) | John B. McKay |

| Flight 153 | 14 October 1965 | 3,554 mph (5,720 km/h) | 50.4 miles (81.1 km) | Joseph H. Engle |

| Flight 174 | 1 November 1966 | 3,750 mph (6,040 km/h) | 58.1 miles (93.5 km) | Bill Dana |

| Flight 190 | 17 October 1967 | 3,856 mph (6,206 km/h) | 53.1 miles (85.5 km) | Pete Knight |

| Flight 191 | 15 November 1967 | 3,569 mph (5,744 km/h) | 50.3 miles (81.0 km) | Michael J. Adams† |

| Flight 197 | 21 August 1968 | 3,443 mph (5,541 km/h) | 50.6 miles (81.4 km) | Bill Dana |

† fatal

Fastest flights

| Flight | Date | Top Speed | Altitude | Pilot |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flight 45 | 9 November 1961 | 4,092 mph (6,585 km/h) | 19.2 miles (30.9 km) | Robert M. White |

| Flight 59 | 27 June 1962 | 4,104 mph (6,605 km/h) | 23.4 miles (37.7 km) | Joe Walker |

| Flight 64 | 26 July 1962 | 3,989 mph (6,420 km/h) | 18.7 miles (30.1 km) | Neil Armstrong |

| Flight 86 | 25 June 1963 | 3,910 mph (6,290 km/h) | 21.7 miles (34.9 km) | Joe Walker |

| Flight 89 | 18 July 1963 | 3,925 mph (6,317 km/h) | 19.8 miles (31.9 km) | Robert Rushworth |

| Flight 97 | 5 December 1963 | 4,017 mph (6,465 km/h) | 19.1 miles (30.7 km) | Robert Rushworth |

| Flight 105 | 29 April 1964 | 3,905 mph (6,284 km/h) | 19.2 miles (30.9 km) | Robert Rushworth |

| Flight 137 | 22 June 1965 | 3,938 mph (6,338 km/h) | 29.5 miles (47.5 km) | John B. McKay |

| Flight 175 | 18 November 1966 | 4,250 mph (6,840 km/h) | 18.7 miles (30.1 km) | Pete Knight |

| Flight 188 | 3 October 1967 | 4,519 mph (7,273 km/h) | 36.3 miles (58.4 km) | Pete Knight |

X-15 pilots

| X-15 pilots and their achievements during the program | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pilot | Organization | Total Flights |

USAF space flights |

FAI space flights |

Max Mach |

Max speed (mph) |

Max altitude (miles) |

| Michael J. Adams† | U.S. Air Force | 7 | 1 | 0 | 5.59 | 3,822 | 50.3 |

| Neil Armstrong | NASA | 7 | 0 | 0 | 5.74 | 3,989 | 39.2 |

| Scott Crossfield | North American Aviation | 14 | 0 | 0 | 2.97 | 1,959 | 15.3 |

| Bill Dana | NASA | 16 | 2 | 0 | 5.53 | 3,897 | 58.1 |

| Joseph H. Engle | U.S. Air Force | 16 | 3 | 0 | 5.71 | 3,887 | 53.1 |

| Pete Knight | U.S. Air Force | 16 | 1 | 0 | 6.70 | 4,519 | 53.1 |

| John B. McKay | NASA | 29 | 1 | 0 | 5.65 | 3,863 | 55.9 |

| Forrest S. Petersen | U.S. Navy | 5 | 0 | 0 | 5.3 | 3,600 | 19.2 |

| Robert A. Rushworth | U.S. Air Force | 34 | 1 | 0 | 6.06 | 4,017 | 53.9 |

| Milt Thompson | NASA | 14 | 0 | 0 | 5.48 | 3,723 | 40.5 |

| Joe Walker | U.S. Air Force | 25 | 3 | 2 | 5.92 | 4,104 | 67.0 |

| Robert M. White* | U.S. Air Force | 16 | 1 | 0 | 6.04 | 4,092 | 59.6 |

| † Killed • * White was backup for Captain Iven Kincheloe | |||||||

See also

Related lists

- List of rocket planes

- List of X-15 flights

- List of space disasters

References

- Notes

- ↑ "Aerospaceweb.org | Aircraft Museum X-15". Aerospaceweb.org, 24 November 2008.

- ↑ Jenkins, Dennis R. Space Shuttle: The History of the National Space Transportation System: The First 100 Missions, 3rd edition. Stillwater, Minnesota: Voyageur Press, 2001. ISBN 0-9633974-5-1.

- ↑ "NASA astronaut wings award ceremony". NASA Press Release, 23 August 2005.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Käsmann 1999, p. 105.

- ↑ X-15A Crash site

- ↑ United States Air Force Museum 1975, p. 73.

- Bibliography

- American X-Vehicles: An Inventory X-1 to X-50, SP-2000-4531 - June 2003; NASA online PDF Monograph

- Flight experience with shock impingement and interference heating on the X-15-2 research airplane 1968 - NASA (PDF format)

- Godwin, Robert, ed. X-15: The NASA Mission Reports. Burlington, Ontario: Apogee Books, 2001. ISBN 1-896522-65-3.

- Hallion, Dr. Richard P. "Saga of the Rocket Ships." AirEnthusiast Six March-June 1978. Bromley, Kent, UK: Pilot Press Ltd., 1978.

- Käsmann, Ferdinand C.W. "Die schnellsten Jets der Welt". Weltrekord-Flugzeuge [World Speed Record Aircraft] (in German). Kolpingring, Germany: Aviatic Verlag, 1999. ISBN 3-925505-26-1.

- "Thermal protection system X-15A-2 Design report." NASA report 1968 (PDF format).

- Thompson, Milton O. and Neil Armstrong. At the Edge of Space: The X-15 Flight Program. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1992. ISBN 1-56098-107-5.

- Tregaskis, Richard. X-15 Diary: The Story of America's First Space Ship. Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse.com, 2000. ISBN 0-595-00250-1.

- United States Air Force Museum Guidebook. Wright-Patterson AFB, Ohio: Air Force Museum Foundation, 1975.

- "X-15 research results with a selected bibliography." NASA report (PDF format).

- "X-15: Extending the Frontiers of Flight." NASA (PDF format).

External links

- NASA's X-15 website

- X-15 Research Results With a Selected Bibliography (NASA SP-60, 1965)

- "Transiting from Air to Space: The North American X-15" (1998)

- "Proceedings of the X-15 First Flight 30th Anniversary Celebration, 8 June 1989"

- (PDF) Hypersonics Before the Shuttle: A Concise History of the X-15 Research Airplane (NASA SP-2000-4518, 2000)

- A Field Guide to American Spacecraft - Locations of X-15 aircraft

- unofficial X-15 website

- X-15 Research Results (1964)

- X-15 photos at Dryden

- Encyclopedia Astronautica's X-15 chronology

- Major Michael Adams Monument

- X15 site in French, with detailed flight reports

- Aerospace Legacy Foundation

- X-15, X-15A-2 • Dimensional references, plans and images (Primary source: NASA Technical Reports)

- Interview with Neil Armstrong about his experience in the X-15

- X-15 at the Internet Movie Database

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||