Weaving

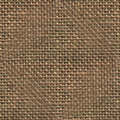

Weaving is a textile craft in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads, called the warp and the filling or weft (older woof), are interlaced to form a fabric or cloth. The warp threads run lengthways on the piece of cloth, and the weft runs across from side to side, across the bolt of cloth.

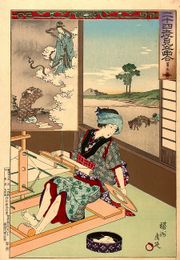

Cloth is woven on a loom, a device that holds the warp threads in place while filling threads are woven through them. Weft is an old English word meaning "that which is woven".[1]

The way the warp and filling threads interlace with each other is called the weave. The majority of woven products are created with one of three basic weaves: plain weave, satin weave, or twill.

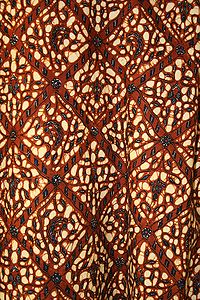

Woven cloth can be plain (in one colour or a simple pattern), or can be woven in decorative or artistic designs, including tapestries. Fabric in which the warp and/or weft is tie-dyed before weaving is called ikat.

The ancient craft of handweaving, along with hand spinning, remains a popular craft. The majority of commercial fabrics in the West are woven on computer-controlled Jacquard looms. In the past, simpler fabrics were woven on dobby looms, while the Jacquard harness adaptation was reserved for more complex patterns. Some believe the efficiency of the Jacquard loom, with its Jacquard weaving process, makes it more economical for mills to use them to weave all of their fabrics, regardless of the complexity of the design.

Contents |

Process

In general, weaving involves the interlacing of two sets of threads at right angles to each other: the warp and the weft. The warp are held taut and in parallel order, typically by means of a loom, though some forms of weaving may use other methods. The loom is warped (or dressed) with the warp threads passing through heddles on two or more harnesses. The warp threads are moved up or down by the harnesses creating a space called the shed. The weft thread is wound onto spools called bobbins. The bobbins are placed in a shuttle that carries the weft thread through the shed. The raising and lowering sequence of warp threads gives rise to many possible weave structures:

- plain weave,

- twill weave,

- satin weave, and

- complex computer-generated interlacings.

Both warp and weft can be visible in the final product. By spacing the warp more closely, it can completely cover the weft that binds it, giving a warpfaced textile such as rep weave. Conversely, if the warp is spread out, the weft can slide down and completely cover the warp, giving a weftfaced textile, such as a tapestry or a Kilim rug. There are a variety of loom styles for hand weaving and tapestry. In tapestry, the image is created by placing weft only in certain warp areas, rather than across the entire warp width.

Ancient and traditional cultures

There are some indications that weaving was already known in the Palaeolithic era. An indistinct textile impression has been found at Pavlov, Moravia. Neolithic textiles are well known from finds in pile dwellings in Switzerland. One extant fragment from the Neolithic was found in Fayum, at a site dated to about 5000 BCE. This fragment is woven at about 12 threads by 9 threads per cm in a plain weave. Flax was the predominant fibre in Egypt at this time and continued popularity in the Nile Valley, even after wool became the primary fibre used in other cultures around 2000 BCE. Another Ancient Egyptian item, known as the Badari dish, depicts a textile workshop. This item, catalogue number UC9547, is now housed at the Petrie Museum and dates to about 3600 BCE. Enslaved women worked as weavers during the Sumerian Era. They washed wool fibers in hot water and wood-ash soap and then dried them. Next, they beat out the dirt and carded the wool. The wool was then graded, bleached, and spun into a thread. The spinners pulled out fibers and twisted them together. This was done either by rolling fibers between palms or using a hooked stick. The thread was then placed on a wooden or bone spindle and rotated on a clay whorl, which operated like a flywheel.

The slaves then worked in three-woman teams on looms, where they stretched the threads, after which they passed threads over and under each other at perpendicular angles. The finished cloth was then taken to a fuller.

Easton's Bible Dictionary (1897) points to numerous Biblical references to weaving in ancient times:

Weaving was an art practised in very early times (Ex. 35:35). The Egyptians were specially skilled in it (Isa. 19:9; Ezek. 27:7), and some have regarded them as its inventors.

In the wilderness, the Hebrews practised it (Ex. 26:1, 8; 28:4, 39; Lev. 13:47). It is referred to in subsequent times as specially the women's work (2 Kings 23:7; Prov. 31:13, 24). No mention of the loom is found in Scripture, but we read of the "shuttle" (Job 7:6), "the pin" of the beam (Judg. 16:14), "the web" (13, 14), and "the beam" (1 Sam. 17:7; 2 Sam. 21:19). The rendering, "with pining sickness," in Isa. 38:12 (A.V.) should be, as in the Revised Version, "from the loom," or, as in the margin, "from the thrum." We read also of the "warp" and "woof" (Lev. 13:48, 49, 51–53, 58, 59), but the Revised Version margin has, instead of "warp," "woven or knitted stuff."

American Southwest

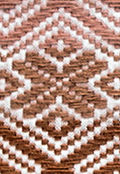

Textile weaving, using cotton dyed with pigments, was a dominant craft among pre-contact tribes of the American southwest, including various Pueblo peoples, the Zuni, and the Ute tribes. The first Spaniards to visit the region wrote about seeing Navajo blankets. With the introduction of Navajo-Churro sheep, the resulting woolen products have become very well known. By the 1700s the Navajo had begun to import yarn with their favorite color, Bayeta red. Using an upright loom, the Navajos wove blankets and then rugs after the 1880s for trade. Navajo traded for commercial wool, such as Germantown, imported from Pennsylvania. Under the influence of European-American settlers at trading posts, Navajos created new and distinct styles, including "Two Gray Hills" (predominantly black and white, with traditional patterns), "Teec Nos Pos" (colorful, with very extensive patterns), "Ganado" (founded by Don Lorenzo Hubbell), red dominated patterns with black and white, "Crystal" (founded by J. B. Moore), Oriental and Persian styles (almost always with natural dyes), "Wide Ruins," "Chinlee," banded geometric patterns, "Klagetoh," diamond type patterns, "Red Mesa" and bold diamond patterns. Many of these patterns exhibit a fourfold symmetry, which is thought to embody traditional ideas about harmony, or hózhó.

Amazonia

In Native Amazonia, densely woven palm-bast mosquito netting, or tents, were utilized by the Panoans, Tupí, Western Tucano, Yameo, Záparoans, and perhaps by the indigenous peoples of the central Huallaga River basin (Steward 1963:520). Aguaje palm-bast (Mauritia flexuosa, Mauritia minor, or swamp palm) and the frond spears of the Chambira palm (Astrocaryum chambira, A.munbaca, A.tucuma, also known as Cumare or Tucum) have been used for centuries by the Urarina of the Peruvian Amazon to make cordage, net-bags hammocks, and to weave fabric. Among the Urarina, the production of woven palm-fiber goods is imbued with varying degrees of an aesthetic attitude, which draws its authentication from referencing the Urarina’s primordial past. Urarina mythology attests to the centrality of weaving and its role in engendering Urarina society. The post-diluvial creation myth accords women’s weaving knowledge a pivotal role in Urarina social reproduction.[2] Even though palm-fiber cloth is regularly removed from circulation through mortuary rites, Urarina palm-fiber wealth is neither completely inalienable, nor fungible since it is a fundamental medium for the expression of labor and exchange. The circulation of palm-fiber wealth stabilizes a host of social relationships, ranging from marriage and fictive kinship (compadrazco, spiritual compeership) to perpetuating relationships with the deceased.[3]

Islamic world

Hand weaving of Persian carpets and kilims has been an important element of the tribal crafts of many of the subregions of modern day Iran. Examples of carpet types are the Lavar Kerman carpet from Kerman and the Seraband rug from Arak.

An important innovation in weaving that was developed in the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age was the introduction of foot pedals to operate a loom. The first such devices appeared in Syria, Iran and Islamic parts of East Africa, where "the operator sat with his feet in a pit below a fairly low-slung loom." By 1177, it was further developed in Al-Andalus, where having the mechanism was "raised higher above the ground on a more substantial frame." This type of loom spread to the Christian parts of Spain and soon became popular all over medieval Europe.[4]

Europe

Dark Age and Medieval Europe

Weighted-warp looms were commonplace in Europe until the development of more advanced looms around the 10th–11th centuries. Especially in colder climates, where a large floor loom would take up too much valuable floor space, the more primitive looms remained in use until the 20th Century to produce "homespun" cloth for individual family needs. The primary material woven in most of Europe was wool, though linen was also common, and imported silk thread was occasionally made into cloth. Both men and women were weavers, though the task often fell to the wife of a farming household. Fabric width was limited to the reach of the weaver, but was sufficient for the tunic-style garments worn in much of Europe at the time. A plain weave or twill was common, since professional weavers with skills to produce better fabrics were rare.

Weaving was a strictly local enterprise until later in the period, when larger weaving operations sprung up in places like Brugges, in Flanders. Within this setting, master weavers could improve their craft and pass skills along to apprentices. As the Middle Ages progressed, significant trade in fine cloth developed, and loom technology improved to allow very thin threads to be woven. Weaver's guilds (and associated craft guilds, like fullers) gained significant political and economic power in some of the bigger weaving cities.

In the medieval period, weaving was considered part of the set of seven mechanical arts.

Colonial America

Colonial America was heavily reliant on Great Britain for manufactured goods of all kinds. British policy was to encourage the production of raw materials in colonies. Weaving was not prohibited, but the export of British wool was. As a result many people wove cloth from locally produced fibers in Colonial America.

In Colonial times the colonists mostly used wool, cotton and flax (linen) for weaving, though hemp fiber could be made into serviceable canvas and heavy cloth also. They could get one cotton crop each fall, but until the invention of the cotton gin it was a labor-intensive process to separate the seeds from the cotton fiber. Flax and hemp were harvested in the summer, and the stalks rendered for the long fibers within. Wool could be sheared up to twice yearly, depending on the breed of sheep.

A plain weave was preferred in Colonial times, and the added skill and time required to make more complex weaves kept them from common use in the average household. Sometimes designs were woven into the fabric but most were added after weaving using wood block prints or embroidery.

Industrial Revolution

Before the Industrial Revolution, weaving remained a manual craft, usually undertaken part-time by family craftspeople. Looms might be broad or narrow; broad looms were those too wide for the weaver to pass the shuttle through the shed, so that the weaver needed an assistant (often an apprentice). This ceased to be necessary after John Kay invented the flying shuttle in 1733, which also sped up the process of weaving.

Great Britain

The first attempt to mechanise weaving was the work of Edmund Cartwright from 1785. He built a factory at Doncaster and obtained a series of patents between 1785 and 1792. In 1788, his brother Major John Cartwight built Revolution Mill at Retford (named for the centenary of the Glorious Revolution. In 1791, he licensed his loom to the Grimshaw brothers of Manchester, but their Knott Mill burnt down the following year (possibly a case of arson). Edmund Cartwight was granted a reward of £10,000 by Parliament for his efforts in 1809.[5] However, success in power-weaving also required improvements by others, including H. Horrocks of Stockport. Only during the two decades after about 1805, did power-weaving take hold. Textile manufacture was one of the leading sectors in the British Industrial Revolution, but weaving was a comparatively late sector to be mechanised. The loom became semi-automatic in 1842 with Kenworthy and Bulloughs Lancashire Loom. The various innovations took weaving from a home-based artisan activity (labour intensive and man-powered) to steam driven factories process. A large metal manufacturing industry grew to produce the looms, firms such as Howard & Bullough of Accrington, and Tweedales and Smalley and Platt Brothers. Most cotton weaving took place in weaving sheds, in small towns circling Greater Manchester and worsted weaving in West Yorkshire – men and women with weaving skills emigrated, and took the knowledge to their new homes in New England, in places like Pawtucket and Lowell.

The invention in France of the Jacquard loom, enabled complicated patterned cloths to be woven, by using punched cards to determine which threads of coloured yarn should appear on the upper side of the cloth.

America, 1800–1900

The Jacquard loom attachment was perfected in 1801, and was becoming common in Europe by 1806. It came to the US in the early 1820's, some immigrant weavers bringing jacquard equipment with them, and spread west from New England. At first it was used with traditional human-powered looms. As a practical matter, previous looms were mostly limited to the production of simple geometric patterns. The jacquard allowed individual control of each warp thread, row by row without repeating, so very complex patterns were suddenly feasible. Jacquard woven coverlets (bedspreads) became popular by mid-century, in some cases being custom-woven with the name of the customer embedded in the programmed pattern. Undyed cotton warp was usually combined with dyed wool weft.

Natural dyes were used until just before the American Civil War, when artificial dyes started to come into use.

See also

- Kilim

- Persian weave

- Textile manufacturing terminology

- Weaving (mythology)

- Basket weaving

Notes

- ↑ deriving from an obsolete past participle of weave (Oxford English Dictionary, see "weft" and "weave".

- ↑ Bartholomew Dean 2009 Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia, Gainesville: University Press of Florida ISBN 978-081303378 [1]

- ↑ Bartholomew Dean. "Multiple Regimes of Value: Unequal Exchange and the Circulation of Urarina Palm-Fiber Wealth" Museum Anthropology February 1994, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 3–20 available online)(paid subscription).

- ↑ Pacey, Arnold (1991), Technology in world civilization: a thousand-year history, MIT Press, pp. 40–1, ISBN 0262660725

- ↑ W. English, The Textile Industry (1969), 89–97; W. H. Chaloner, People and Industries (1093), 45–54

References

- This article incorporates text from Textiles by William H. Dooley, Boston, D.C. Heath and Co., 1914, a volume in the public domain and available online from Project Gutenberg

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)