Viola

A viola shown from the front and the side |

|

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | French: alto; German: Bratsche |

| Hornbostel-Sachs classification | 321.322-71 (Composite chordophone sounded by a bow) |

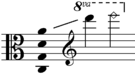

| Playing range | |

|

|

| Related instruments | |

|

|

| Musicians | |

|

|

The viola (pronounced /viˈoʊlə/ or /vaɪˈoʊlə/[1]) is a bowed string instrument. It is the middle voice of the violin family, between the violin and the cello.

The casual observer may mistake the viola for the violin because of their similarity in size, closeness in pitch range (the viola is a perfect fifth below the violin), and nearly identical playing position. However, the viola's timbre sets it apart: its rich, dark-toned sonority is more full-bodied than the violin's. As its mellow voice is frequently used for playing inner harmonies, the viola does not enjoy the wide solo repertoire or fame of the violin.

Contents |

Form of the viola

The viola is similar in material and construction to the violin but is larger in size and more variable in its proportions. A "full-size" viola's body is between one and four inches longer than the body of a full-size violin (i.e., between 15 and 18 inches (38 and 46 cm)), with an average length of about 16 inches (41 cm). Small violas made for children typically start at 12 inches (30 cm), which is equivalent to a half-size violin. Often, a fractional-sized violin will be strung with the strings of a viola (C, G, D and A) for those children who need even smaller sizes.[2] Unlike the violin, the viola does not have a standard full size. The body of a viola would need to measure about 21 inches (53 cm) long to match the acoustics of a violin, making it impractical to play in the same manner as the violin.[3] For centuries, viola makers have experimented with the size and shape of the viola, often tweaking the proportions or shape of the instrument to make an instrument with a shorter scale length and lighter weight, but that still has a large enough sound box to create an unmistakable "viola sound."

Experiments with the size of the viola have tended to increase it in the interest of improving the instrument's sound. These include Hermann Ritter's "viola alta", an instrument measuring about 18.9 inches (48 cm) intended for use in Richard Wagner's operas.[4] The Tertis model viola, which has wider bouts and deeper ribs to promote a better viola tone, is another slightly "non-standard" shape that allows the player to use a larger instrument. Many experiments with the acoustics of a viola, particularly increasing the size of the body, result in a much deeper tone of the instrument, making the instrument resemble the tone of a cello. Since many composers wrote for a traditional-sized viola, changes in the tone of a viola, particularly in orchestral music, can have unintended consequences on the balance in ensembles.

More recent (and more radically shaped) innovations address the ergonomic problems of playing the viola by making it shorter and lighter while finding ways to keep the traditional sound. These include Otto Erdesz "cutaway" viola (which has one shoulder cut out to make shifting easier);[5] the "Oak Leaf" viola (which has two extra bouts); viol shaped violas like Joseph Curtin's "Evia" model (which also utilizes a moveable neck and a maple-veneered carbon fiber back to reduce weight):[6] violas played in the same manner as cellos (see vertical viola); and the eye-catching "Dalí-esque" shapes of both Bernard Sabatier's violas in fractional sizes (which appear to have melted) and of David Rivinus' "Pellegrina" model violas.[7]

Other experiments besides those dealing with the "ergonomics vs. sound" problem have appeared. American composer Harry Partch fitted a viola with a cello neck to allow the use of his 43-tone scale. Luthiers have also created five-stringed violas, which allow a greater playing range. Modern music is played on these instruments, but viol music can be played as well.

Playing the viola

A person who plays the viola is called a violist or simply a viola player. While it is similar to the violin, the technique required for playing viola has many differences. The difference in size accounts for some of the technical differences, as notes are spread out farther along the fingerboard often requiring different fingerings. The less responsive strings and heavier bow warrant a somewhat different bowing technique. The viola requires the player to lean more intensely on the strings compared to the violin.

- Compared to violin, the viola will generally have a larger body as well as a longer string length, which is why younger violists or even some old tend to get smaller sized violas for easier playing. The most immediately noticeable adjustments a player accustomed to playing violin has to make are to use wider-spaced fingerings. It is common for some players to use a wider and more intense vibrato in the left hand facilitated by employing the fleshier pad of the finger rather than the tip, and to hold the bow and right arm farther away from the player's body. The player must also bring the left elbow farther forward or around, so as to reach the lowest string. This allows the fingers to be firm and create a clearer tone. Unless the violist is gifted with especially large hands, different fingerings are often used, including frequent use of half position and shifting position, where on the violin staying in one place would suffice.

- The viola is generally strung with thicker strings than the violin. This, combined with its larger size and lower pitch range, results in a deeper and mellower tone. However, the thicker strings also mean that the viola "speaks" more slowly than its soprano cousin. Practically speaking, if a violist and violinist are playing together, the violist must begin moving the bow a fraction of a second sooner than the violinist to produce a sound that starts at the same moment as the violinist's sound. The thicker strings also mean that more weight must be applied with the bow to make them speak.

- The viola bow has a wider band of horsehair than a violin bow, particularly noticeable near the frog (or "heel" in the UK). Viola bows (70 to 74 g) are heavier than violin bows (58 to 61 g). The profile of the outside corner of a viola bow frog generally is rounded, compared to the rectangular corner usually seen on violin bows.

Tuning

The viola's four strings are normally tuned in fifths: C3 (an octave below middle C) is the lowest, with G3, D4 and A4 above it. This tuning is exactly one fifth below the violin, so that they have three strings in common—G, D, and A—and is one octave above the cello. Although the violin and viola have three strings tuned the same, the tone quality or sound color is markedly different.

Violas are tuned by turning the pegs near the scroll, which the strings are wrapped around. Tightening the string raises the pitch; loosening the string lowers the pitch. The A string is normally tuned first, typically to 440 Hz or 442 Hz (see pitch). The other strings are then tuned to it in intervals of perfect fifths, bowing two strings simultaneously. Most violas also have adjusters (also called fine tuners) that are used to make finer changes. These permit the tension of the string to be adjusted by rotating a small knob at the opposite end of the string, at the tailpiece. Such tuning is generally easier to learn than using the pegs, and adjusters are usually recommended for younger players and put on smaller violas, although they are usually used in conjunction with one another. Adjusters work best, and are most useful, on higher tension metal strings. It is common to use one on the A string even if the others are not equipped with them. The picture on the right shows normal stringing of the pegs. Some violists reverse the stringing of the C and G pegs, so the thicker C string does not turn so severe an angle over the nut, although this is uncommon.

Small, temporary tuning adjustments can also be made by stretching a string with the hand. A string may be tuned down by pulling it above the fingerboard, or tuned up by pressing the part of the string in the pegbox. These techniques may be useful in performance, reducing the ill effects of an out-of-tune string until an opportunity to tune properly.

The tuning C-G-D-A is used for the great majority of all viola music. However, other tunings are occasionally employed both in classical music (where the technique is known as scordatura) and in some folk styles. Mozart, in his Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Viola and Orchestra, which is in E flat, wrote the viola part in D major and specified that the viola strings were to be raised in pitch by a semitone; his intention was probably to give the viola a brighter tone to avoid it being overpowered by the rest of the ensemble. Lionel Tertis, in his transcription of the Elgar cello concerto, wrote the slow movement with the C string tuned down to B flat, enabling the viola to play one passage an octave lower. Occasionally the C string may also be tuned up to D.

Viola organizations and research

A renewal of interest in the viola by performers and composers in the twentieth century also led to increased research devoted to the instrument. Paul Hindemith and Vadim Borisovsky made an early attempt at an organization in 1927 with the Violists' World Union. But it was not until 1968 with the creation of the Viola-Forschungsgellschaft, now the International Viola Society (IVS), that a lasting organization would take hold. The IVS now consists of twelve sections around the world, the largest being the American Viola Society (AVS), which publishes the Journal of the American Viola Society. In addition to the journal, the AVS sponsors the David Dalton Research Competition and the Primrose International Viola Competition.

The 1960s also saw the beginning of several research publications aimed at the viola, beginning with Franz Zeyringer's Literatur für Viola, which has undergone several versions, the most recent in 1985. Maurice Riley produced the first attempt at a comprehensive history of the viola in his History of the Viola from 1980, followed with a second volume in 1991. The IVS published the multi-language Viola Yearbook from 1979 to 1994, and several other national sections of the IVS publish newsletters. The Primrose International Viola Archive at Brigham Young University houses the most substantial amount of material related to the viola, including scores, recordings, instruments, and archival materials from some of the world's greatest violists.

Viola music

Reading music

Sheet music written for the viola differs from that of other instruments in that it primarily uses alto clef (sometimes called "viola clef"), which is otherwise rarely used. Viola sheet music also employs the treble clef when there are substantial sections of music written in higher registers. The note A4 is above the top line of the clef, D4 is in the second space down, G3 is in the space at the bottom of the staff, and C3 is two spaces under the staff.

Role of the viola in pre-twentieth century works

In early orchestral music, the viola part was frequently limited to the filling in of harmonies with little melodic material assigned to it. When the viola was given melodic parts in music of that era, it was often duplication in unison or octaves of whatever other strings played. A notable exception is J.S. Bach's Brandenburg Concerto No. 6, which placed the two violas in the primary melodic role (it was scored for 2 violas, cello, 2 violas da gamba, and continuo).

An example of a piece written before the 20th century that features a solo viola part is Hector Berlioz's Harold in Italy, though there are also a few Baroque and Classical concerti, such as those by Telemann (one of the earliest viola concertos known), Franz Anton Hoffmeister and Carl Stamitz.

The viola plays an important role in chamber music. Mozart succeeded in liberating the viola somewhat when he wrote his six string quintets, which are widely considered to include some of his greatest works. The quintets use two violas, which frees the instrument (especially the first viola) for solo passages and increases the variety and richness of the ensemble. Mozart also wrote for the viola in his Sinfonia Concertante in which the two solo instruments, viola and violin, are equally important. Another important contribution was a set of two duets for violin and viola, as well as his Kegelstatt Trio for viola, clarinet, and piano. The young Felix Mendelssohn wrote a little-known viola sonata in C minor (without opus number, but dating from 1824). From his earliest works Johannes Brahms wrote music that features the viola prominently. Among his first published pieces of chamber music, the sextets for strings Op.18 and Op.36 contain what amounts to solo parts for both violas. Late in life he wrote two greatly admired sonatas for clarinet and piano, his Opus 120 (1894); later Brahms transcribed these works for the viola (the horn part in his horn trio is also available in a transcription for viola). Brahms also wrote Two Songs for Alto with Viola and Piano (Zwei Gesänge für eine Altstimme mit Bratsche und Pianoforte), Op. 91, "Gestillte Sehnsucht" or "Satisfied Longing" and "Geistliches Wiegenlied" or "Spiritual Lullaby," which was a present for the famous violinist Joseph Joachim and his wife, Amalie. Antonín Dvořák played the viola, and apparently said it was his favorite instrument; his chamber music is rich in important parts for the viola. Another Czech composer, Bedřich Smetana, included a significant viola part in his quartet "From My Life"; the quartet begins with an impassioned statement by the viola. (Incidentally, Dvořák was the violist at the premiere.) It should also be noted that Bach, Mozart and Beethoven all occasionally played the viola part in chamber music.

The viola occasionally has a major role in orchestral music, for example the sixth variation of the Enigma Variations by Edward Elgar, called "Ysobel". Another prominent example is the Richard Strauss "Don Quixote" for solo cello and solo viola.

While the viola repertoire is quite large, the amount written by well-known pre-twentieth century composers is relatively small. There are many transcriptions of works for other instruments for the viola, and the large amount of 20th-century literature is very diverse. See "The Viola Project" at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, where Professor of Viola Jodi Levitz has paired a composer with each of her students, resulting in a recital of brand-new works played for the very first time.

Twentieth century and beyond

In the earlier part of the 20th century, more composers began to write for the viola, encouraged by the emergence of specialized soloists such as Lionel Tertis. Englishmen Arthur Bliss, York Bowen, Benjamin Dale, and Ralph Vaughan Williams all wrote chamber and concert works for Tertis. William Walton, Bohuslav Martinů and Béla Bartók wrote well-known viola concertos. One of the few composers to write a substantial amount of music for the viola was Paul Hindemith; being himself a violist, he often performed the premieres of his own viola works. Debussy's Sonata for Flute, Viola and Harp has inspired a significant number of other composers to write for this combination. Elliott Carter also wrote several fine works for viola including his Elegy (1943) for viola and piano; it was subsequently transcribed for clarinet. Ernest Bloch, a Swiss-born American composer best known for his compositions inspired by Jewish music, wrote two famous works for viola, the Suite 1919 and the Suite Hebraique for solo viola and orchestra. Rebecca Clarke was a 20th century composer and violist who also wrote extensively for the viola. Lionel Tertis records that Edward Elgar (whose cello concerto Tertis transcribed for viola, with the slow movement in scordatura), Alexander Glazunov (who wrote an Elegy, op. 44, for viola and piano), and Maurice Ravel all promised concertos for viola, yet all three died before doing any substantial work on them. In the latter part of the 20th century a substantial repertoire was produced for the viola; many composers including Alfred Schnittke, Sofia Gubaidulina, Giya Kancheli and Krzysztof Penderecki, have written viola concertos. The American composer Morton Feldman wrote a series of works entitled The Viola in My Life, which feature concertante viola parts.

In spectral music, the viola has been sought after because of its lower overtone partials that are more easily heard than on the violin. Spectral composers like Giacinto Scelsi, Gerard Grisey, Tristan Murail and Horatiu Radulescu have written solo works for viola.

Contemporary pop music

The viola is sometimes used in contemporary popular music, mostly in the avant-garde. The influential group Velvet Underground famously used the viola, as do some modern groups such as 10,000 Maniacs, Defiance, Ohio, The Funetics, Flobots, Beethoven's 5th, British Sea Power and others. Jazz music has also seen its share of violists, from those used in string sections in the early 1900s to a handful of quartets and soloists emerging from the 1960s onward. It is quite unusual though, to use individual string instruments in contemporary popular music. It is usually the flute or rather the full orchestra appearing to be the favoured choice, rather than a lone string player. The upper strings could be easily drowned out by the other instruments, especially if electric, or even by the singer.

See The viola in popular music below.

Viola in folk music

Although not as commonly used as the violin in folk music, the viola is nevertheless used by many folk musicians across the world. Extensive research into the historical and current use of the viola in folk music has been carried out by Dr. Lindsay Aitkenhead. Players in this genre include Eliza Carthy, Mary Ramsey, Helen Bell, and Nancy Kerr. Clarence "Gatemouth" Brown was the viola's most prominent exponent in the genre of blues.

The viola is also an important accompaniment instrument in Hungarian and Romanian folk string band music, especially in Transylvania. Here the instrument has three strings tuned g — d' - a (note that the a is an octave lower than found on the standard instrument), and the bridge is flattened with the instrument playing chords in a strongly rhythmic manner. In this usage, it is called a kontra or brácsa (pronounced "bra-cha").

Violists

The term "violist" is not used universally in English; "viola player" is in common usage in British English, as the word "violist" is used to mean "player of the viol".

There are few truly well-known viola virtuosi, perhaps because little virtuoso viola music was written before the twentieth century. Pre-twentieth century viola players of note include Alessandro Rolla, Antonio Rolla, Chrétien Urhan, Casimir Ney, Louis van Waefelghem, and Hermann Ritter. The most important viola pioneers from the twentieth century were Lionel Tertis, William Primrose, Paul Hindemith, Théophile Laforge, Cecil Aronowitz, Maurice Vieux, Vadim Borisovsky, Lillian Fuchs, Frederick Riddle, Walter Trampler, Ernst Wallfisch, and Emanuel Vardi, the first violist to record the 24 Caprices by Paganini on viola. Many noted violinists have publicly performed and recorded on the viola as well, among them Eugène Ysaÿe, Yehudi Menuhin, David Oistrakh, Pinchas Zukerman, Maxim Vengerov, Julian Rachlin and Nigel Kennedy.

Among the great composers, several preferred the viola to the violin when playing in ensembles,[8] the most noted being Ludwig van Beethoven, Johann Sebastian Bach[9] and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Numerous other composers also chose to play the viola in ensembles, including Joseph Haydn, Franz Schubert, Felix Mendelssohn, Antonín Dvořák, and Benjamin Britten. Among those noted both as violists and as composers are Rebecca Clarke and Paul Hindemith. Contemporary composer and violist Kenji Bunch has written a number of viola solos.

Viola in popular music

The viola sees limited use in popular music. It was sometimes part of popular dance orchestras in the period from about 1890 to 1930, and orchestrations of pop tunes from that era often had viola parts available. The viola largely disappeared from pop music at the start of the big band era. With the Charlie Daniels Band, Charlie Daniels has played viola instead of violin for some of the fiddling "Redneck Fiddlin' Man."

John Cale, a classically trained violist, played the instrument to great effect (amplified and often distorted) on some Velvet Underground tracks, most notably on "Venus in Furs", "Heroin", "The Black Angel's Death Song", "Stephanie Says", and "Hey Mr. Rain". He also played viola on "We Will Fall," a track on the debut Stooges album, which he also produced.

Producer and songwriter Don Kayvan is a classically trained violist and regularly uses the viola on rap, r&b, alternative and pop songs.

Singer-songwriter Patrick Wolf is a trained violinist and viola player, and regularly uses viola in his songs and onstage.

Kansas' "Dust in the Wind", as well as other tracks by the band, features a viola melody. Robby Steinhardt played violin, viola, and cello on the song, and he or David Ragsdale plays at least one of these on most Kansas songs during their membership.

The Who's "Baba O'Riley" from the album Who's Next features an extended viola solo played by Dave Arbus of East of Eden.

Dave Swarbrick of the English Folk-Rock group Fairport Convention has been known to contribute viola among other stringed instruments to the band, most notably on the Liege & Lief album on the track "Medley..." where he plays violin with an overdubbed viola playing the same part an octave lower.

Geoffrey Richardson is a classically trained violist and multi-instrumentalist best known for his work with Caravan, Murray Head and the Penguin Cafe Orchestra over more than 3 decades, though he has also performed and recorded with many other artists and bands.

Billy Currie played viola (as well as keyboards and violin) with the British bands Ultravox and Visage, which had their biggest success in the early 1980s.

A viola accompaniment, played by Toni Marcus, to four tracks on Van Morrison's album Into the Music can be heard. The tracks are: "Steppin' Out Queen"; "And the Healing Has Begun"; "It's All in the Game" and "You Know What They're Writing About". Also in the video of Van Morrison's performance of "Sweet Thing" live at the Hollywood Bowl, which was released on CD and DVD of a live performance of the album Astral Weeks, there is a considerable viola accompaniment and solo played by Tony Fitzgibbon.

Anna Bulbrook plays viola in the indie rock group The Airborne Toxic Event.

The Goo Goo Dolls featured the viola in "We are the Normal"

Frank Sweeney played viola in the proto-indie group The June Brides and also features on the track "Imperial" by Primal Scream.

The Beatles uses two violas in the accompaniment of "Hello, Goodbye".

The viola has made a slight comeback in modern pop music; aided and abetted by string groups, Bond and Wild. The band Flobots makes extensive use of the viola on nearly all of their songs as bandmember Mackenzie Roberts is a violist. In her latest album, Lonely Runs Both Ways, Alison Krauss uses the viola in many of her songs. Vienna Teng, a folk/indie artist, used the viola as a solo instrument in two of her songs from her recent album Dreaming Through the Noise (2006). Norwegian noise rock band Noxagt had a viola player until very recently; this musician left the band and was replaced by a baritone guitarist. New indie pop band The Funetics, use two violas and guitar for its instrumentation. The Six Parts Seven also used a viola. Neo-new wave indie rock band The Rentals features classically trained violist Lauren Chipman.

Vampire Weekend featured a viola during their song "The Kids Don't Stand a Chance" on their 2008 self-titled debut album. This was the most notable appearance of the viola on the album. Although, the instrument makes appearances throughout the album, often with the rest of the quartet.

Warren Ellis from The Dirty Three, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds and Grinderman has increasingly played the viola on recent recordings, in particular on The Bad Seeds' Dig, Lazarus, Dig!!! album.

Kris Allen, winner of American Idol Season 8, also plays the viola; he began playing at College Station Elementary School, and continued playing until he graduated from Mills University Studies High School under James Hatch. Allen made the Arkansas All-State Orchestra.

Electric violas

Amplification and equalization can make up for the weaker output of a violin string tuned to notes below G3, so most electric instruments with lower strings are violin-sized, and as such, are called "violins." Comparatively fewer electric violas do exist, for those who prefer the physical size or familiar touch references of a viola-sized instrument. Welsh musician John Cale, formerly of The Velvet Underground, is one of the more famous users of such an electric viola, who has used them both for melodies in his solo work and for drones in his work with The Velvet Underground (e.g. "Venus in Furs").

Instruments may be built with an internal preamplifier, or may put out the unbuffered transducer signal. While such raw signals may be fed directly to an amplifier or mixing board, they often benefit from an external preamp/equalizer on the end of a short cable, before being fed to the sound system.

Audio examples

See also

- List of compositions for viola

- Lionel Tertis International Viola Competition

- Maurice Vieux International Viola Competition

- Primrose International Viola Competition

- American Viola Society

- International Viola Society

- Tenor violin

- Vertical viola

- Viola d'amore

References

- ↑ Only the pronunciation /viˈoʊlə/ (vee-OH-lə) is used in US English, but both this pronunciation and /vaɪˈoʊlə/ (vye-OH-lə) are used in UK English, as shown by the entries in the American Heritage Dictionary, Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary, and Oxford Advanced Learner's Dictionary). Compare with the US and UK pronunciations of the flower called viola.

- ↑ "Violin and Viola". Oakville Suzuki Association. 2009. http://www.oakvillesuzuki.org/content.php?content_pg_id=5. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- ↑ "The Violin Octet". The New Violin Family Association, Inc. 2004-2007. http://www.newviolinfamily.org/8tet.html. Retrieved 2008-03-22.

- ↑ Maurice, Joseph. "Michael Balling: Pioneer German Solo Violist with a New Zealand Interlude". Journal of the American Viola Society (Summer 2003). http://www.americanviolasociety.org/JAVS%20Online/Summer%202003/Balling/Balling.htm. Retrieved 2006-07-31.

- ↑ Curtin, Joseph. "Otto Erdesz Remembered". The Strad (November 2000). http://www.josephcurtinstudios.com/news/strad/nov00/Erdesz_bio.htm. Retrieved 2006-07-30.

- ↑ Curtin, Joseph. Project Evia "Project Evia". American Lutherie Journal No 60 (Winter 1999). http://www.josephcurtinstudios.com/innovation/project_evia.htm Project Evia. Retrieved 2006-10-08.

- ↑ http://www.rivinus-instruments.com/Pellegrina.htm

- ↑ Groves Dictionary

- ↑ Forkel, Johann Nikolaus (in German). Ueber Johann Sebastian Bachs Leben, Kunst und Kunstwerke. Herausgegeben und eingeleitet von Claudia Maria Knispel. Berlin: Henschel Verlag.

Bibliography

- Dalton, David. "The Viola & Violists." Primrose International Viola Archive. Retrieved October 8, 2006

- Chapman, Eric. "Joseph Curtin and the Evia". Journal of the American Viola Society, Vol.20, No.1, Spring 2004, pp. 41–42.

- Curtin, Joseph. "Otto Erdesz Remembered". The Strad, November 2000. Retrieved July 30, 2006

- Curtin, Joseph. "Project Evia" (Retrieved October 8, 2006). American Lutherie Journal, No. 60, Winter 1999.

- Maurice, Joseph. "Michael Balling: Pioneer German Solo Violist with a New Zealand Interlude." Journal of the American Viola Society, Summer 2003. Retrieved July 31, 2006.

External links

- International Viola Society website

- American Viola Society website

- Primrose International Viola Archive library website

- Viola web site, with links to resources & viola societies

- Rivinus- David Rivinus' site with pictures of his oddly shaped violas

- Curtin - Joseph Curtin's "Evia" (Experimental viola) model

- Viola in music - The role of viola in music. Information, description of works, videos, free sheet music, MIDI files, RSS update.

- Anechoic Recordings of Viola Tones - University of Iowa Electronic Music Studios

- Brothers Gahl fighting violism – a film made by the Oslo String Quartet

- Dr. Lindsay Aitkenhead's folk viola research page.

- Nigel Keay's Contemporary Viola - Articles with a focus on contemporary repertoire for the viola.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Viola". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. Very brief, but it does have names for the viola in French, German and Italian.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Viola". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press. Very brief, but it does have names for the viola in French, German and Italian.