Upanishads

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures |

|---|

|

| Vedas |

| Rigveda · Yajurveda Samaveda · Atharvaveda |

| Vedangas |

| Shiksha · Chandas Vyakarana · Nirukta Kalpa · Jyotisha |

| Upanishads |

| Rig vedic Aitareya Yajur vedic

Brihadaranyaka · Isha Taittiriya · Katha Shvetashvatara Sama vedic

Chandogya · Kena Atharva vedic

Mundaka · Mandukya Prashna |

| Puranas |

| Brahma puranas Brahma · Brahmānda Brahmavaivarta Markandeya · Bhavishya Shiva puranas

Shiva · Linga Skanda · Vayu |

| Epics |

| Ramayana Mahabharata (Bhagavad Gita) |

| Other scriptures |

| Manu Smriti Artha Shastra · Agama Tantra · Sūtra · Stotra Dharmashastra Divya Prabandha Tevaram Ramcharitmanas Yoga Vasistha |

| Scripture classification |

| Śruti · Smriti |

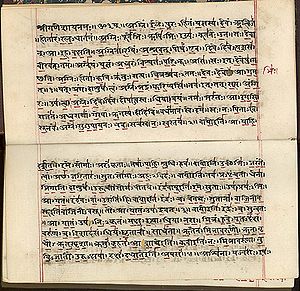

The Upanishads (Devanagari: उपनिषद्, IAST: Upaniṣad, also spelled "Upaniṣad") are philosophical texts of the Hindu religion. More than 200 are known, of which the first dozen or so, the oldest and most important, are variously referred to as the principal, main (mukhya) or old Upanishads. The oldest of these, the Brihadaranyaka and Chandogya Upanishads, were composed during the pre-Buddhist era of India.[1][2] while the Taittiriya, Aitareya and Kausitaki, which show Buddhist influence, must have been composed after the fifth century BC:[2] the remainder of the mukhya Upanishads are dated to the first two centuries of the common era.[2] The new Upanishads were composed in the medieval and early modern period: discoveries of newer Upanishads were being reported as late as 1926.[3] One, the Muktika Upanishad, predates 1656[4] and contains a list of 108 canonical Upanishads,[5] including itself as the last. However, several texts under the title of "Upanishads" originated up to the end of the British rule in 1947, some of which did not deal with subjects of vedic philosophy.[6] The newer Upanishads are known to be imitations of the mukhya Upanishads.

The Upanishads have been attributed to several composers: Yajnavalkya and Uddalaka Aruni feature prominently in the early Upanishads.[7] Other important composers include Shwetaketu, Shandilya, Aitreya, Pippalada and Sanat Kumara. Important women authors include Yajnavalkya's wife Maitreyi and Gari. Dara Shikoh, son of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, translated fifty Upanishads into Persian in 1657. The first written English translation came in 1804 from Max Müller, who was aware of 170 Upanishads. Sadhale's catalog from 1985, the Upaniṣad-vākya-mahā-kośa, lists 223 Upanishads.[8] The Upanishads are mostly the concluding part of the Brahmanas and the transition from the latter to the former is identified as the Aranyakas.[9]

All Upanishads have been passed down in oral tradition. The mukhya Upanishads hold the stature of revealed texts (shruti). With the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahmasutra[10] the mukhya Upanishads provide a foundation for several later schools of Indian philosophy (vedanta), among them two influential monistic schools of Hinduism.[11][12][13] Adi Sankara and Ramanuja, who taught two different variants of Advaita, wrote extensive exegeses on Upnishads and derived the authority of their respective positions from their interpretation.[14][15] A third major interpreter of Upanishadic canon was Madhvacharya whose commentaries presented a dualistic or Dvaita interpretation of these texts which was directly opposed to Advaita positions argued by Adi Sankara and Ramanuja.[16]

The Upanishads are collectively considered amongst the 100 Most Influential Books Ever Written by the British poet Martin Seymour-Smith.

Contents |

Etymology

The Sanskrit term Upaniṣad derives from upa- (nearby), ni- (at the proper place, down) and sad ("sitting down near"), implying sitting near a teacher to receive instruction[17] or, alternatively, "laying siege" to the teacher.[18] Monier-Williams adds that "according to native authorities Upanishad means 'setting to rest ignorance by revealing the knowledge of the supreme spirit.'"[19] A gloss of the term Upanishad based on Shankara's commentary on the Kaṭha and Brihadaranyaka Upanishads equates it with Ātmavidyā, that is, "knowledge of the Self", or Brahmavidyā "knowledge of Brahma". Other dictionary meanings include "esoteric doctrine" and "secret doctrine".[20]

Classification

There are more than two hundred known Upanishads, one of which, the Muktika, gives a list of one hundred and eight Upanishads – this number corresponding to the traditional number of beads on a rosary or mala. Modern scholars recognize the first ten, eleven, twelve or thirteen Upanishads as principal or Mukhya Upanishads and the remainder as derived from this ancient canon. If a Upanishad has been commented upon or quoted by revered thinkers like Shankara it is a Mukhya Upanishad,[9] accepted as shruti by most Hindus.

The new Upanishads recorded in the Muktika probably originated in southern India.[21] and are grouped according to their subject as (Sāmānya) Vedānta (philosophical), Yoga, Sanyasa (of the life of renuciation), Vaishnava (dedicated to the god Vishnu), Saiva(dedicated to Shiva) and Sakti (dedicated to the goddess).[22] Several notable and widely used Shakta Upaniṣads including the {{IAST|Kaula, the Śrīvidyā and the Śrichakra are not listed in the Muktika Upanishad. New Upaniṣads are often sectarian since sects have sought to legitimize their texts by claiming for them the status of Śruti.[23]

Another way of classifying the Upanishads is to associate them with the respective Brahmanas. The Jaiminīya Upaniṣadbrāhmaṇa, belonging to the late Vedic Sanskrit period, may also be included. Of nearly the same age are the Aitareya, Kauṣītaki and Taittirīya Upaniṣads, while the remnant date from the time of transition from Vedic to Classical Sanskrit.

Mukhya Upanishads

The Mukhya Upanishads can themselves be stratified into periods. Of the early period are the Brihadaranyaka and the Chandogya, the most important and the oldest, of which the former is the older of the two, though some parts which were composed after the Chandogya.[24] These are believed to pre-date Gautam Buddha (c.500BC).

The Aitareya, Taittiriya, Kausitaki, Mundaka, Prasna, and Kathaka Upaniṣads show Buddha's influence and must have been composed after the fifth century BCE. In the first two centures CE there followed the Kena, Mandukya and Isa Upanishads.[25] Not much is known about the authors except those few, like Yajnavalkayva and Uddalaka, mentioned in the texts:[9] a few women authors, such as Gargi and Maitreyi, the wife of Yajnavalkayva,[26] also feature occasionally.

Each of the principal Upanishads can be associated with one of the schools of exegesis of the four Vedas (shakhas).[27] 1131 Shakhas are said to have existed, of which only a few remain. The new Upanishads often have little relation to the Vedic corpus and have not been cited or commented upon by any great Vedanta philosopher: their language differs from that of the classic Upanishads, being less subtle and more formalized. As a result, they are not difficult to comprehend for the modern reader.[28]

| Veda | Recension | Shakha | Principal Upanishad |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rig Veda | Only one recension | Shakala | Aitareya |

| Sama Veda | Only one recension | Kauthuma | Chāndogya |

| Jaiminiya | Kena | ||

| Ranayaniya | |||

| Yajur Veda | Krishna Yajur Veda | Katha | Kaṭha |

| Taittiriya | Taittirīya and Śvetāśvatara | ||

| Maitrayani | Maitrāyaṇi | ||

| Hiranyakeshi (Kapishthala) | |||

| Kathaka | |||

| Shukla Yajur Veda | Vajasaneyi Madhyandina | Bṛhadāraṇyaka and Īṣa | |

| Kannav | |||

| Atharva | Only one recension | Shaunaka | Māṇḍūkya and Muṇḍaka |

The Kauśītāki and Maitrāyaṇi Upanishads are sometimes added to the list of the mukhya Upanishads.

New Upanishads

There is no fixed list of the Upanishads as newer ones are constantly being composed:[29] whenever older Upanishads do not suit the founders of new sects they compose new ones of their own.[30] 1908 marked the discovery of four new Upanishads, named Bashkala, Chhagaleya, Arsheya and Saunaka, by Dr. Friedrich Schrader,[31] who attributed them to the first prose period of the Upanishads.[32] The text of three, the Chhagaleya, Arsheya and Saunaka, was reportedly corrupt and neglected but possibly re-constructable with the help of their Perso-Latin translations. Texts called "Upanishads" continued to appear up to the end of the British rule in 1947. The Akbar Upanishad and Allah Upanishad are examples,[6] having been written in the seventeenth century, at the instance of Darah Shikoh, in praise of Islam.[33]

The main Shakta Upanishads mostly discuss doctrinal and interpretative differences between the two principal sects of a major Tantric form of Shaktism called Shri Vidya upasana. The many extant lists of authentic Shakta Upaniṣads vary, reflecting the sect of their compilers, so that they yield no evidence of their 'location' in Tantric tradition, impeding correct interpretation.The Tantra content of these texts also weakens its identity as an Upaniṣad for non-Tantrikas and therefore its status as shruti and thus its authority.[34]

Philosophy

Two words that are of paramount importance in grasping the Upanishads are Brahman and Atman.[35] The Brahman is the universal spirit and the Atman is the individual Self.[36] Differing opinions exist amongst scholars regarding the etymology of these words. Brahman probably comes from the root brh which means to grow.[37] The present day connotation of Brahman is "the source of all existence or from whom the universe has grown". Brahman is the ultimate, both transcendent and immanent, the absolute infinite existence, the sum total of all that ever is, was, or shall be. The word atman's original meaning was probably "breath" and it now means the soul of a living creature, especially of a human being. The discovery by the Upanashidic thinkers that Atman and Brahman are one and the same is the greatest contribution made to the thought of the world.[38][39][40][41]

The Brihadaranyaka and the Chandogya are the most important of the mukhya Upanishads. They represent two main schools of thought within the Upanishads. The Brihadaranyaka deals with acosmic or nis-prapancha, whereas the Chandogya deals with the cosmic or sa-prapancha.[9] Between the two, the Brihadaranyaka is the more original one.[42]

The Upanishads also contain the first and most definitive explications of the divine syllable Aum, the cosmic vibration that underlies all existence. The mantra Aum Shanti Shanti Shanti translated as "the soundless sound, peace, peace, peace" is often found in the Upanishads. The path of bhakti or 'Devotion to God' is foreshadowed in Upanishadic literature, and was later realized by texts such as the Bhagavad Gita.[43]

Important quotations from some of the Upanishads include:

- Prajñānam brahma meaning "Consciousness is Brahman" from the Aitareya Upanishad[44]

- Aham brahmāsmi meaning "I am Brahman" from the Brihadaranyaka[45]

- Tat tvam asi meaning "Thou art that" from the Chandogya[46]

- Ayamātmā brahmā meaning "This Atman is Brahman" from the Mandukya[47]

Metaphysics

The three main approaches in arriving at the solution to the problem of the Ultimate Reality have traditionally been the theological, the cosmological and the psychological approaches.[48] The cosmological approach involves looking outward, to the world, the psychological approach meaning looking inside or to the self and the theological approach is looking upward or to God. Descartes takes the first and starts with the argument that the Self is the primary reality, self-consciousness the primary fact of existence, and introspection the start of the real philosophical process.[49] According to him, we can arrive at the conception of God only through the Self because it is God who is the cause of the Self and thus we should regard God as more perfect than the Self. Spinoza on the other hand believes that God is the be-all and the end-all of all things, the alpha and the omega of existence. From God philosophy starts, and in god philosophy ends. The manner of approach of the Upanishadic philosophers to the problem of ultimate reality was neither the Cartesian nor the Spinozistic one. The Upanishadic philosophers regarded the Self as the ultimate existence and subordinated the World and God to the Self. The Self to them, is more real than either the World or God. It is only ultimately that they identify the Self with god, and thus bridge over the gulf that exists between the theological and psychological approaches to Reality. They take the cosmological approach to start with but they find that this cannot give them the solution of the Ultimate reality. So the Upanishadic thinkers go back and start over by taking the psychological approach and here again they cannot find the solution to the Ultimate Reality. So they perform yet another experiment by taking the theological approach. They find that this too is lacking in finding the solution. They give yet another try to the psychological approach and come up with the solution to the problem of the Ultimate Reality. Thus the Upanishadic thinkers follow a cosmo-theo-psychological approach.[49] A study of the mukhya Upanishads show that the Upanishadic thinkers progressively build on each others ideas. They go back and forth and refute improbable approaches before arriving at the solution of the Ultimate Reality.[50]

Schools of Vedanta

The source for all schools of Vedānta are the three texts – the Upanishads, the Bhagavad Gita and the Brahmasutras.[51] Two different types of the non-dual Brahman-Atman are presented in the Upanishads:[52]

- The one in which the non-dual Brahman-Atman is the all inclusive ground of the universe and

- The one in which all reality in the universe is but an illusion

The later theistic (Dvaita and Visistadvaita) and absolutist (Advaita) schools of Vendanta are made possible because of the difference between these two views. The three main schools of Vedanta are Advaita, Dvaita and Vishishtadvaita. Other schools of Vedanta made possible by the Upanishads include Nimbarka's Dvaitadvaita, Vallabha's Suddhadvaita and Chaitanya's Acintya Bhedabheda.[53] The philosopher Adi Sankara has provided commentaries on eleven mukhya Upanishads.[54]

Advaita is considered the most influential sub-school of the Vedānta school of Hindu philosophy,[55] though it does not represent the mainstream Hindu position.[56] Gaudapada was the first person to expound the basic principles of the Advaita philosophy in a commentary on the apparently conflicting statements of the Upanishads.[57] Advaita literally means non-duality, and it is a monistic system of thought.[55] It deals with the non-dual nature of the Brahman and the Atman. The Advaita school is said to have been consolidated by Shankara. He was a pupil of Gaudapada's pupil. Radhakrishnan believed that Shankara's views of Advaita are straightforward developments of the Upanishads and the Brahmasutra and he offered no innovations to these,[58], while other scholars find sharp differences between Shankara's writings and the Brahmasutra,[59][60] and that there are many ideas in the Upanishads at odds with those of Shankara.[61] Gaudapada lived in a time when Buddhism was widely prevalent in India, and he is at times conscious of the similarity between his system to some phases of Buddhist thought.[57] His main work is infused with philosophical terminology of Buddhism, and uses Buddhist arguments and analogies.[62] Towards the end of his commentary on the topic, he clearly says "This was not spoken by Buddha". Although there are a wide variety of philosophical positions propounded in the Upanishads, commentators since Adi Shankara have usually followed him in seeing idealist monism as the dominant force.[63][64][65][66][67]

The Dvaita school was founded by Madhvacharya. Born in 1138 near Udipi,[68] Dvaita is regarded as the best philosophic exposition of theism.[69] Sharma points out that Dvaita, a term commonly used to designate Madhava's system of philosophy, translates as "dualism" in English. The Western understanding of dualism equates to two independent and mutually irreducible substances. The Indian equivalent of that definition would be Samkya Dvaita.[70] Madhva's Dvaita differs from the Western definition of dualism in that while he agrees to two mutually irreducible substances that constitute reality, he regards only one, God, as being independent.[70]

The third school of Vedanta is the Vishishtadvaita, which was founded by Ramanuja. Traditional dates of his birth and death are given as 1017 and 1137 though a shorter life span somewhere between these two dates has been suggested. Modern scholars conclude that on the whole Ramanuja's theistic views may be closer to those of the Upanishads than are Shankara's, and Ramanuja's interpretations are in fact representative of the general trend of Hindu thought. Ramanuja strenuously refuted Shankara's works.[56] Visistadvaita is a synthetic philosophy of love that tries to reconcile the extremes of the other two monistic and theistic systems of vedanta.[69] It is called Sri-Vaisanavism in its religious aspect. Chari claims that has been misunderstood by its followers as well as its critics. Many, including leading modern proponents of this system forget that jiva is a substance as well as an attribute and call this system "qualified non-dualism" or the adjectival monism. While the Dvaita insists on the difference between the Brahman and the Jiva, Visistadvaita states that God is their inner-Self as well as transcendent.

Development

Chronology and geography

Scholars disagree about the exact dates of the composition of the Upanishads. Different researchers have provided different dates for the Vedic and Upanashic eras. Ranade criticizes Deussen for assuming that the oldest Upanishads were written in prose, followed by those that were written in verse and the last few again in prose. He proposes a separate chronology based on a battery of six tests.[71] The tables below summarize some of the prominent work:[72]

|

|

The general area of the composition of the early Upanishads was northern India, the region bounded on the west by the Indus valley, on the east by lower Ganges river, on the north by the Himalayan foothills and on the south by the Vindhya mountain range. There is confidence about the early Upanishads being the product of the geographical center of ancient Brahmanism, comprising the regions of Kuru-Panchala and Kosala-Videha together with the areas immediately to the south and west of these.[73]

While significant attempts have been made recently to identify the exact locations of the individual Upanishads, the results are tentative. Witzel identifies the center of activity in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad as the area of Videha, whose king, Janaka features prominently in the Upanishad. Yajnavalkya is another individual who features prominently, almost as the personal theologian of Janaka.[74] Brahmins of the central region of Kuru-Panchala rightly considered their land as the place of the best theological and literary activityes since this was the heartland of Brahmanism of the late Vedic period. The setting of the third and the fourth chapters of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishads was probably intended to show that Yajnavalkya of Videha defeated all the best theologians of the Kuru Panchala thereby demonstrating the rise of Videha as a center of learning. The Chandogya Upanishad was probably composed in a more Western than an Eastern location, probably somewhere in the western region of the Kuru-Panchala country.[75] The great Kuru-Panchala theologian Uddalaka Aruni who was vilified in the Brihadaranyaka features prominently in the Chandogya Upanishad. Compared to the Principal Upanishads, the new Upanishads recorded in the Muktika belong to an entirely different region, probably southern India, and are considerably relatively recent.[21]

Development of thought

While the hymns of the Vedas emphasize rituals and the Brahmanas serve as a liturgical manual for those Vedic rituals, the spirit of the Upanishads is inherently opposed to ritual.[76] The older Upanishads launch attacks of increasing intensity on the ritual. Anyone who worships a divinity other than the Self is called a domestic animal of the gods in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad. The Chandogya Upanishad parodies those who indulge in the acts of sacrifice by comparing them with a procession of dogs chanting Om! Let's eat. Om! Let's drink. The Mundaka launches the most scathing attack on the ritual by comparing those who value sacrifice with an unsafe boat that is endlessly overtaken by old age and death.[76]

The opposition to the ritual is not explicit all the time. On several occasions the Upanishads extend the task of the Aranyakas by making the ritual allegorical and giving it a philosophical meaning. For example, the Brihadaranyaka interprets the practice of horse-sacrifice or ashvamedha allegorically. It states that the over-lordship of the earth may be acquired by sacrificing a horse. It then goes on to say that spiritual autonomy can only be achieved by renouncing the universe which is conceived in the image of a horse.[76]

In similar fashion, the pattern of reducing the number of gods in the Vedas becomes more emphatic in the Upanishads. When Yajnavalkaya is asked how many gods exist, he decrements the number successively by answering thirty-three, six, three, two, one and a half and finally one. Vedic gods such as the Rudras, Visnu, Brahma are gradually subordinated to the supreme, immortal and incorporeal Brahman of the Upanishads. In fact Indra and the supreme deity of the Brahamanas, Prajapati, are made door keepers to the Brahman's residence in the Kausitaki Upanishad.[76]

In short, the one reality or ekam sat of the Vedas becomes the ekam eva a-dvitiyam or "the one and only and sans a second" in the Upanishads.[76]

Worldwide transmission

.jpg)

Given that Indian Brahmin seers are reputed to have visited Greece, it may be that the Upanishadic sages influenced Ancient Greek philosophy. Many ideas in Plato's Dialogues, particularly, have Indian analogues: Several concepts in the Platonic psychology of reason bear resemblance to the gunas of Indian philosophy. Professor Edward Johns Urwick conjectures that The Republic owes several central concepts to Indian influence.[77][78] Garb and West have also concluded that this was due to Indian influence.[79][80]

A. R. Wadia dissents in that Plato's metaphysics were rooted in this life,[77] the primary aim being an ideal state. He later proposed a state less ordered but more practicable and conducive to human happiness. As for the Upanishadic thinkers, their goal was not an ideal state or society but moksha or deliverance form the endless cycle of birth and death. Wadia concludes that there was no exchange of information and ideas between Plato and the Upanishadic thinkers: Plato remains Greek and the Indian sages remain Indian.[77]

The Upanishads were a part of an oral tradition. Their study was confined to the higher castes of Indian society.[81] Sudras and women were not given access to them soon after their composition. The Upanishads have been translated in to various languages including Persian, Italian, Urdu, French, Latin, German, English, Dutch, Polish, Japenese, and Russian.[82] The Moghul Emperor Akbar's reign (1556–1586) saw the first translations of the Upanishads into Persian,[83][84] and his great-grandson, Dara Shikoh, produced a collection called Sirr-e-Akbar (The Greatest Mysteries) in 1657 with the help of Sanskrit Pandits of Varansi. Its introduction states that the Upanishads constitute the Qur'an's "Kitab al-maknun" or hidden book.[85][86] But Akbar's and Sikoh's translations remained unnoticed in the Western world until 1775.[83]

Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron, a French Orientalist who had lived in India between 1755 and 1761, received a manuscript of the Upanishads in 1775 from M. Gentil and translated it into French and Latin, publishing the Latin translation in two volumes in 1802–1804 as Oupneck'hat.[87] The French translation was never published.[88] The first German translation appeared in 1832 and Roer's English version appeared in 1853. However Max Mueller's 1879 and 1884 editions were the first systematic English treatment to include the twelve Principal Upanishads.[82] After this the Upanishads were rapidly translated into Dutch, Polish, Japenese and Russian.

Global scholarship and praise

The German philosopher Schopenhauer read the Latin translation and praised the Upanishads in his main work, The World as Will and Representation (1819), as well as in his Parerga and Paralipomena (1851).[89] He found his own philosophy was in accord with the Upanishads, which taught that the individual is a manifestation of the one basis of reality. For Schopenhauer, that fundamentally real underlying unity is what we know in ourselves as "will." Schopenhauer used to keep a copy of the Latin Oupnekhet by his side and is said to have commented "It has been the solace of my life, it will be the solace of my death".[90] Another German philosopher, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, praised the mystical and spiritual aspects of the Upanishads.[91] Schelling and other philosophers associated with German idealism were dissatisfied with Christianity as propagated by churches. They were fascinated with the Vedas and the Upanishads.[91] Similarly-minded English and European writers, such as Thomas Carlyle, Victor Cousin, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Mme. de Staël, claimed to find deep wisdom in these non-Western writings. In the United States, the group known as the Transcendentalists were influenced by the German idealists. These Americans, such as Emerson and Thoreau, were not satisfied with traditional Christian mythology and therefore embraced Schelling's interpretation of Kant's Transcendental idealism, as well as his celebration of the romantic, exotic, mystical aspect of the Upanishads. As a result of the influence of these writers, the Upanishads gained renown in Western countries.[92] Erwin Schrödinger, the great quantum physicist said "The multiplicity is only apparent. This is the doctrine of the Upanishads. And not of the Upanishads only. The mystical experience of the union with God regularly leads to this view, unless strong prejudices stand in the West."[93] Eknath Easwaran in translating the Upanishads articulates how they "form snapshots of towering peaks of consciousness taken at various times by different observers and dispatched with just the barest kind of explanation".[94]

Criticism of the Upanishads

Citicisms of the Upanishads range from an ill-conceived and half-thought out bluster[97] to scholarly but scathing ones. An early European writer on the Upanishads writes:

| “ | They are the work of a rude age, a deteriorated race, and a barbarous and unprogressive community. | ” |

|

—An early European writer[97] |

||

The Brihadaranyaka gives an unorthodox explanation of the origin of the caste-system. It says that a similar four-tier caste system existed in heaven which is now replicated on earth.[98] This has been criticized by the Dalit leader Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar. He studied the philosophy of the Upanishads pragmatically and concluded that they were most ineffective and inconsequential piece of speculation and that they had no effect on the moral and social order of the Hindus. Ambedkar implies that the voluminous Upanishads are a useless work because of their inability to affect any change in the caste-biased, inherently unequal Hindu society. He dismisses the Upanishads by quoting Huxley in saying that Upanishadic philosophy can be reduced to very few words. Ambedkar agrees with Huxley:

| “ | In supposing the existence of a permanent reality, or 'substance', beneath the shifting series of phenomena, whether of matter or of mind. The substance of the cosmos was `Brahma', that of the individual man `Atman'; and the latter was separated from the former only, if I may so speak, by its phenomenal envelope, by the casing of sensations, thoughts and desires, pleasures and pains, which make up the illusive phantasmagoria of life. This the ignorant, take for reality; their `Atman' therefore remains eternally imprisoned in delusions, bound by the fetters of desire and scourged by the whip of misery. | ” |

|

—Thomas Huxley[99] |

||

According to another writer, David Kalupahana, the Upanishadic thinkers came to consider change as a mere illusion, because it could not be reconciled with a permanent and homogeneous reality. They were therefore led to a complete denial of plurality.[100] He states that philosophy suffered a setback because of the transcendentalism resulting from the search of the essential unity of things.[101] Kalupahana explains further that reality was simply considered to be beyond space, time, change and causlity. This caused change to be a mere matter of words, nothing but a name and due to this, metaphysical speculation took the upper hand. As a result the Upanishads fail to give any rational explanation of the experience of things.[101] Paul Deussen criticizes the idea of unity in the Upanishads as it excluded all plurality, and therefore, all proximity in space, all succession in time, all interdependence as cause and effect, and all opposition as subject and object.[102]

Association with Vedas

All Upanishads are associated with one of the four Vedas—Rigveda, Samaveda, Shukla Yajurveda, Krishna Yajurveda, and Atharvaveda. The Muktika Upanishad's list of 108 Upanishads groups the first ten as mukhya, twenty-one as Sāmānya Vedānta, twenty-three as Sannyāsa, nine as Shākta, thirteen as Vaishnava, fourteen as Shaiva and seventeen as Yoga.[103] The 108 Upanishads as recorded in the Muktika are shown in the table below.[104][105] The mukhya Upanishads are highlighted.

| Veda | Mukhya | Sāmānya | Sannyāsa | Śākta | Vaiṣṇava | Śaiva | Yoga |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ṛgveda | Aitareya | Kauśītāki, Ātmabodha, Mudgala | Nirvāṇa | Tripura, Saubhāgya, Bahvṛca | - | Akṣamālika (Mālika) | Nādabindu |

| Samaveda | Chāndogya, Kena | Vajrasūchi, Mahad, Sāvitrī | Āruṇeya, Maitrāyaṇi, Maitreyi, Sannyāsa, Kuṇḍika | - | Vāsudeva, Avyakta | Rudrākṣa, Jābāla | Yogachūḍāmaṇi, Darśana |

| Krishna Yajurveda | Taittirīya, Śvetāśvatara, Kaṭha | Sarvasāra, Śukarahasya, Skanda (Tripāḍvibhūṭi), Śārīraka, Ekākṣara, Akṣi, Prāṇāgnihotra | Brahma, Śvetāśvatara, Garbha, Tejobindu, Avadhūta, Kaṭharudra, Varāha | Sarasvatīrahasya | Nārāyaṇa (Mahānārāyaṇa), Kali-Saṇṭāraṇa (Kali) | Kaivalya, Kālāgnirudra, Dakṣiṇāmūrti, Rudrahṛdaya, Pañcabrahma | Amṛtabindu, Amṛtanāda, Kṣurika, Dhyānabindu, Brahmavidyā, Yogatattva, Yogaśikhā, Yogakuṇḍalini |

| Shukla Yajurveda | Bṛhadāraṇyaka, Īṣa | Subāla, Mantrikā, Nirālamba, Paiṅgala, Adhyātmā, Muktikā | Jābāla, Paramahaṃsa, Advayatāraka, Bhikṣu, Turīyātīta, Yājñavalkya, Śāṭyāyani | - | Tārasāra | - | Haṃsa, Triśikhi, Maṇḍalabrāhmaṇa |

| Atharvaveda | Muṇḍaka, Māṇḍūkya, Praśna | Sūrya, Ātmā | Parivrāt (Nāradaparivrājaka), Paramahaṃsaparivrājaka, Parabrahma | Sītā, Annapūrṇa, Devī, Tripurātapani, Bhāvana | Nṛsiṃhatāpanī, Mahānārāyaṇa (Tripādvibhuti), Rāmarahasya, Rāmatāpaṇi, Gopālatāpani, Kṛṣṇa, Hayagrīva, Dattātreya, Gāruḍa | Śira, Atharvaśikha, Bṛhajjābāla, Śarabha, Bhasma, Gaṇapati | Śāṇḍilya, Pāśupata, Mahāvākya |

See also

- 100 Most Influential Books Ever Written

- Hinduism-related articles

- Hinduism

- Bhagavad Gita

- Vedas

- Upanishad

- Puranas

- Uddhava Gita

- Ashtavakra Gita

- The Ganesha Gita

- Vyadha Gita

- Avadhuta Gita

Notes

- ↑ Olivelle 1998, p. xxxvi.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 King & Acarya 1995, p. 52.

- ↑ Ranade 1926, p. 12.

- ↑ Verma 2009.

- ↑ Sen 1937, p. 19.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Varghese 2008, p. 101.

- ↑ Mahadevan & 1956 pp59-60.

- ↑ Sadhale 1987.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Mahadevan 1956, p. 56.

- ↑ Ranade 1926, p. 205.

- ↑ Advaita Vedanta, generally attributed to Shankara (788–820), advances a non-dualistic (a-dvaita) interpretation of the Upanishads..." The Guru in Indian Catholicism: Ambiguity Or Opportunity of Inculturation, pp 12, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1992

- ↑ "These Upanishadic ideas are developed into Advaita monism. Brahman's unity comes to be taken to mean that appearances of individualities", Classical Indian metaphysics: refutations of realism and the emergence of "new logic" , Stephen H. Phillips, Open Court Publishing, 1995

- ↑ "The doctrine of advaita (non dualism) has is origin in the Upanishads..", Epistemics of Divine Reality , pp 91, Domenic Marbaniang, Domenic Marbaniang

- ↑ "Sankara wrote his commentary on the Upnishads toward the begining of the ninth century CE. Three hundred years later Ramanuja, a sourthern Brahmin and a scholar of the first rank, undertook reinterpretation of the Upanishads in which he challenged some of Sankara's basic assumptions.", Victorian lunatics: a social epidemiology of mental illness in mid-nineteenth century England, pp 81, Marlene Ann Arieno, Susquehanna University Press, 1989

- ↑ "This is far from an accurate picture of what we read in the Upanishads. It has become traditional to view the Upanishads through the lens of Shankara's Advaita interpretation. This imposes the philosophical revolution of about 700 C.E. upon a very different situation 1,000 to 1,500 years earlier. Shankara picked out monist and idealist themes from a much wider philosophical lineup." Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 195

- ↑ The Thirteen Principal Upanishads,pp 480, Robert Ernest Hume,BiblioBazaar, LLC, 2009

- ↑ Macdonell 2004, p. 53.

- ↑ Schayer 1925, pp. 57–67.

- ↑ Monier-Williams, p. 201.

- ↑ Müller 1900, p. lxxxiii.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Deussen 1908, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Varghese 2008, p. 131.

- ↑ Holdrege 1995, pp. 426.

- ↑ Patrick Olivelle, Upaniṣads. Oxford University Press, 1998, pages 3–4

- ↑ Richard King, Early Advaita Vedānta and Buddhism: the Mahāyāna context of the Gauḍapādīya-kārikā. SUNY Press, 1995, ISBN 9780791425138 (page 52).

- ↑ Ranade 1926, p. 61.

- ↑ Joshi 1994, pp. 90–92.

- ↑ Heehs 2002, p. 85.

- ↑ Rinehart 2004, p. 17.

- ↑ Mueller 1859, p. 317.

- ↑ Singh 2002, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Schrader & Adyar Library 1908, p. v.

- ↑ Walker 1968, p. 534.

- ↑ Brooks 1990, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Mahadevan 1956, p. 59.

- ↑ Smith 1995, p. 10.

- ↑ Mahadevan 1956, p. 60.

- ↑ Lanman 1897, p. 790.

- ↑ Brown 1922, p. 266.

- ↑ Slater 1897, p. 32.

- ↑ Varghese 2008, p. 132.

- ↑ Parmeshwaranand 2000, p. 458.

- ↑ Robinson 1992, p. 51..

- ↑ Panikkar 2001, p. 669.

- ↑ Panikkar 2001, pp. 725–727.

- ↑ Panikkar 2001, pp. 747–750.

- ↑ Panikkar 2001, pp. 697–701.

- ↑ Ranade 1926, p. 247.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Ranade 1926, p. 248.

- ↑ Ranade 1926, pp. 249–278.

- ↑ Radhakrishnan 1956, p. 272.

- ↑ Mahadevan 1956, p. 62.

- ↑ Ranade 1926, pp. 179–182.

- ↑ Mahadevan 1956, p. 63.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Klostermaier 2007, pp. 361–363.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Radhakrishnan 1956, p. 273.

- ↑ Radhakrishnan 1956, p. 284.

- ↑ King 1999, p. 221.

- ↑ Nakamura 2004, p. 31.

- ↑ Collins 2000, p. 195.

- ↑ King 1999, p. 219.

- ↑ Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, page 195 [1]: "The breakdown of the Vedic cults is more obscured by retrospective ideology than any other period in Indian history. It is commonly assumed that the dominant philosophy now became an idealist monism, the identification of atman (self) and Brahman (Spirit), and that this mysticism was believed to provide a way to transcend rebirths on the wheel of karma. This is far from an accurate picture of what we read in the Upanishads. It has become traditional to view the Upanishads through the lens of Shankara's Advaita interpretation. This imposes the philosophical revolution of about 700 C.E. upon a very different situation 1,000 to 1,500 years earlier. Shankara picked out monist and idealist themes from a much wider philosophical lineup."

- ↑ Patrick Olivelle, Upaniṣads. Oxford University Press, 1998, page 4: "In this Introduction I have avoided speaking of 'the philosophy of the upanishads', a common feature of most introductions to their translations. These documents were composed over several centuries and in various regions, and it is futile to try to discover a single doctrine or philosophy in them."

- ↑ Ariel Glucklich, The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective. Oxford University Press US, 2008, page 70: "The Upanishadic age was also characterized by a pluralism of worldviews. While some Upanishads have been deemed 'monistic', others, including the Katha Upanishad, are dualistic."

- ↑ Gregory P. Fields, Religious Therapeutics: Body and Health in Yoga, Āyurveda, and Tantra. SUNY Press, 2001, page 26: "The Maitri is one of the Upanishads that inclines more toward dualism, thus grounding classical Samkhya and Yoga, in contrast to the non-dualistic Upanishads eventuating in Vedanta."

- ↑ For instances of Platonic pluralism in the early Upanishads see Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change. Harvard University Press, 2000, pages 197–198.

- ↑ Raghavendrachar 1956, p. 322.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 Chari 1956, p. 305.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Sharma 2000, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Ranade 1926, pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Sharma 1985, pp. 17–19.

- ↑ Olivelle 1998, p. xxxvii.

- ↑ Olivelle 1998, p. xxxviii.

- ↑ Olivelle 1998, p. xxxix.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 76.2 76.3 76.4 Mahadevan 1956, p. 57.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 77.2 Wadia 1956, p. 64-65.

- ↑ Ranade 1925, p. xix.

- ↑ Chousalkar, p. 130.

- ↑ Urwick 1920, p. 14.

- ↑ Sharma 1985, p. 19.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Sharma 1985, p. 20.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Müller 1900, p. lvii.

- ↑ Muller 1899, p. 204.

- ↑ Mohammada 2007, p. 54.

- ↑ Engineer 2006, p. 20.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica 1911.

- ↑ Müller 1900, p. lviii.

- ↑ Schopenhauer & Payne 2000, p. 395.

- ↑ Schopenhauer & Payne 2000, p. 397.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Singh 1999, p. 456-461.

- ↑ Versluis 1993, pp. 69, 76, 95. 106–110.

- ↑ Schrödinger 1992, p. 129.

- ↑ Easwaran 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ Ranade 1926, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Chowdhry 1956, p. 46.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Ranade 1926, p. 11.

- ↑ Ranade 1926, p. 59-60.

- ↑ Singh 2000, pp. 96–97.

- ↑ Kalupahana 1975, p. 14.

- ↑ 101.0 101.1 Kalupahana 1975, p. 15.

- ↑ Deussen 1908, pp. 156.

- ↑ Sri Aurbindo Kapali Sastr Institute of Vedic Culture.

- ↑ Farquhar 1920, p. 364.

- ↑ Parmeshwaranand 2000, pp. 404–406.

References

- Singh, Nagendra Kr (2000), Ambedkar on religion, Anmol Publications, ISBN 9788126105038

- Mahadevan, T. M. P (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

- Ranade, R. D. (1926), A constructive survey of Upanishadic philosophy, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan

- Holdrege, Barbara A. (1995), Veda and Torah, Albany: SUNY Press, ISBN 0791416399

- Rinehart, Robin (2004), Robin Rinehart, ed., Contemporary Hinduism: ritual, culture, and practice, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 9781576079058

- Mueller, Friedrich Max (1859), A history of ancient Sanskrit literature so far as it illustrates the primitive religion of the Brahmans, Williams & Norgate

- Singh, N.K (2002), Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, Anmol Publications PVT. LTD, ISBN 9788174881687

- Brooks, Douglas Renfrew (1990), The Secret of the Three Cities: An Introduction to Hindu Shakta Tantrism, The University of Chicago Press

- Smith, Huston (1995), The Illustrated World’s Religions: A Guide to Our Wisdom Traditions, New York: Labrynth Publishing

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

- Encyclopædia Britannica, Advaita, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/6636/Advaita, retrieved August 10, 2010

- Chari, P. N. Srinivasa (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., History of Philosophy Eastern and Western

- Raghavendrachar, Vidvan H. N (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., History of Philosophy Eastern and Western

- Sharma, B. N. Krishnamurti (2000), Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, ISBN 9788120815759

- Robinson, Catherine (1992), Interpretations of the Bhagavad-Gītā and Images of the Hindu Tradition: The Song of the Lord, Routledge Press

- Anquetil Duperron, Abraham Hyacinthe, Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911, http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/1911_Encyclop%C3%A6dia_Britannica/Anquetil_Duperron,_Abraham_Hyacinthe

- Kalupahana (1975), Causality: The Central Philosophy of Buddhism, The University Press of Hawaii

- Causality: The Central Philosophy of Buddhism, The University Press of Hawaii, 1975

- Sharma, Shubhra (1985), Life in the Upanishads, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 9788170172024

- Easwaran, Eknath (2007), The Upanishads, Nilgiri Press, ISBN 9781586380212

- Joshi, Kireet (1994), The Veda and Indian culture: an introductory essay, Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 9788120808898, http://books.google.com/books?id=1CJlM2nhlt0C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Sadhale, S. Gajanan Shambhu (1987), Sri Garibdass Oriental Series, Delhi: Sri Satguru Publications

- Macdonell, Arthur Anthony (2004), A practical Sanskrit dictionary with transliteration, accentuation, and etymological analysis throughout, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 9788120820005, http://books.google.com/books?id=laIPgMQF_XsC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Monier-Williams, A Sanskrit-English Dictionary, http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/0200/mw__0234.html, retrieved August 10, 2010

- Deussen, Paul (1908), The philosophy of the Upanishads, T. & T. Clark

- Varghese, Alexander P (2008), India : History, Religion, Vision And Contribution To The World, Volume 1, Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, ISBN 9788126909032, http://books.google.com/books?id=y7GKwhuea9kC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Farquhar, John Nicol (1920), An outline of the religious literature of India, H. Milford, Oxford university press

- Parmeshwaranand, Swami (2000), Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Upanisads, Sarup & Sons, ISBN 9788176251488

- Sri Aurbindo Kapali Sastr Institute of Vedic Culture, SAKSIVC: Vedic Literature: Upanishads: 108 Upanishads:, www.vedah.com, http://www.vedah.com/org/literature/upanishads/108Upanishads.asp, retrieved Ausust 10, 2010

- Dr.A.G.Krishna Warrier (translator), Muktika Upanishad, The Theosophical Publishing House, Chennai, http://www.egr.msu.edu/~sundare2/mantra-sangraha/MuktikaUpanishad.pdf., retrieved Ausust 10, 2010

- Sen, Sris Chandra (1937), "Vedic literature and Upanishads", The Mystic Philosophy of the Upanishads, General Printers & Publishers

- Schayer, Stanislaw (1925), Die Bedeutung des Wortes Upanisad, 3, Rocznik Orientalistyczny

- Brodd, Jefferey (2003), World Religions, Winona, MN: Saint Mary's Press, ISBN 9780884897255

- Verma, Rajeev (2009), Faith & philosophy of Hinduism, Volume 1 of Indian religions series, Gyan Publishing House, ISBN 9788178357188, http://books.google.com/books?id=J7AIg5bVFCYC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Müller, Friedrich Max (1900), The Upanishads Sacred books of the East The Upanishads, Friedrich Max Müller, Oxford University Press

- Schopenhauer, Arthur; Payne, E. F.J (2000), E. F. J. Payne, ed., Parerga and paralipomena: short philosophical essays, Volume 2 of Parerga and Paralipomena, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199242214, http://books.google.com/books?id=88CV8JOYUmsC&pg=PA395&lpg=PA395&dq=Some+Remarks+on+Sanskrit+Literature+parerga+and+Paralipomena&source=bl&ots=X5yaMAd1Rm&sig=uNSVpjlI0IPwxF4a3mlXK5TQZgM&hl=en&ei=zaNlTJrAPIbksQPdpo3hDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CBIQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Wadia, A. R (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen & Unwin Ltd

- Collins, Randall (2000), The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, Harvard University Press

- Olivelle, Patrick (1998), Upaniṣads, Oxford University Press

- Glucklich, Ariel (2008), The Strides of Vishnu: Hindu Culture in Historical Perspective, Oxford University Press

- Fields, Gregory P (2001), Religious Therapeutics: Body and Health in Yoga, Āyurveda, and Tantra, SUNY Press

- Chowdhry, Tarapada (1956), Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, ed., History of Philosophy Eastern and Western, George Allen and Unwin Limited, p. 46

- King, Richard; Ācārya, Gauḍapāda (1995), Early Advaita Vedānta and Buddhism: the Mahāyāna context of the Gauḍapādīya-kārikā, SUNY Press, ISBN 9780791425138

- Muller, F. Max (1899), The science of language founded on lectures delivered at the royal institution in 1861 AND 1863, http://books.google.com/books?id=2DQTAAAAQAAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Schrödinger, Erwin (1992), What is life?, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521427081, http://books.google.com/books?id=dg2bYMwdaBwC&printsec=frontcover&dq=9780521427081&hl=en&ei=Wld0TImIA4nCsAOU--TSCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CDQQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Versluis, Arthur (1993), American transcendentalism and Asian religions, Oxford University Press US, ISBN 9780195076585, http://books.google.com/books?id=mNPMzoVEv3sC&printsec=frontcover&dq=9780195076585&hl=en&ei=QVd0TM39H4m-sQPc163dCA&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCgQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Mohammada, Malika (2007), The foundations of the composite culture in India, Aakar Books, ISBN 9788189833183, http://books.google.com/books?id=dwzbYvQszf4C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Engineer, Asgharali (2006), Muslims and India, Gyan Pub. House, ISBN 9788121208826

- Chousalkar, Ashok (1986), Social and Political Implications of Concepts Of Justice And Dharma, Mittal Publications, http://books.google.com/books?id=bsGJNVUMigAC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Urwick, Edward Johns (1920), The message of Plato: a re-interpretation of the "Republic", Methuen & co. ltd

- Panikkar, Raimundo (2001), The Vedic experience: Mantramañjarī : an anthology of the Vedas for modern man and contemporary celebration, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 9788120812802

- Heehs, Peter (2002), Indian religions: a historical reader of spiritual expression and experience, NYU Press, ISBN 9780814736500

- Walker, Benjamin (1968), The Hindu world: an encyclopedic survey of Hinduism, volume 2, Praeger

- Parmeshwaranand, Swami (2000), Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Upanisads, Sarup & Sons, ISBN 9788176251488

- Lanman, Charles R (1897), The Outlook, Volume 56, Outlook Co., http://books.google.com/books?id=M7oRAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA790&dq=The+Outlook+1897+upanishads&hl=en&ei=wH51TLahK4a6sAOtisGgDQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=1&ved=0CCgQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Slater, Thomas Ebenezer (1897), Studies in the Upanishads ATLA monograph preservation program, Christian Literature Society for India

- Brown, Rev. George William (1922), Missionary review of the world, Volume 45, Funk & Wagnalls, http://books.google.com/books?id=klwDAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA266&dq=upanishads+greatest+contribution&hl=en&ei=w391TNRVhKaxA8K4_KAN&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=9&ved=0CFYQ6AEwCDgK#v=onepage&q=upanishads%20greatest%20contribution&f=false

- Schrader, Friedrich Otto; Adyar Library (1908), A descriptive catalogue of the Sanskrit manuscripts in the Adyar Library, Oriental Pub. Co

- Klostermaier, Klaus K. (2007), A survey of Hinduism, SUNY Press

- Ambedkar, Bhimrao (1987), Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings and Speeches, Vol. 3", Government of Mahararasshtra, Bombay, http://www.ambedkar.org/ambcd/17.Philosophy%20of%20Hinduism.htm, retrieved August 8, 2010

- King, Richard (1999), Indian philosophy: an introduction to Hindu and Buddhist thought, Edinburgh University Press

- Nakamura, Hajime (2004), A history of early Vedānta philosophy, Volume 2, Motilal Banarsidass Publ.

Further reading

- Edmonds, I.G (1979), Hinduism, New York: Franklin Watts

- Embree, Ainslie T (1966), The Hindu Tradition, New York: Random House

- Frances Merrett, ed. (1985), The Hindu World, London: MacDonald and Co

- Pandit, Bansi; Glen, Ellyn (1998), The Hindu Mind, B&V Enterprises

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvapalli (1994) [1953], The Principal Upanishads, New Delhi: HarperCollins Publishers India, ISBN 817223124-5

- Wangu, Madhu Bazaz (1991), Hinduism: World Religions, New York: Facts on File

- Max Müller, translator, The Upaniṣads, Part I, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1962, ISBN 0-486-20992-X.

- Max Müller, translator, The Upaniṣads, Part II, New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1962, ISBN 0-486-20993-8.

External links

- Complete set of 108 Upanishads and other documents

- Upanishads at Sanskrit Documents Site

- Complete translation on-line into English of all 108 Upaniṣad-s

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||