USS Monitor

USS Monitor |

|

| Career | |

|---|---|

| Name: | USS Monitor |

| Ordered: | 4 October 1861 |

| Builder: | Continental Iron Works & DeLamater Iron Works (primarily), & others |

| Laid down: | 1861 |

| Launched: | 30 January 1862 |

| Commissioned: | 25 February 1862 |

| Fate: | Lost at sea, 31 December 1862 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Monitor |

| Displacement: | 987 long tons (1,003 t) |

| Length: | 172 ft (52 m) |

| Beam: | 41 ft 6 in (12.65 m) |

| Draft: | 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m) |

| Installed power: | Vibrating-lever steam engine |

| Propulsion: | Screw propeller |

| Speed: | 8 kn (9.2 mph; 15 km/h) |

| Complement: | 59 officers and men |

| Armament: | 2 × 11 in (280 mm) Dahlgren guns |

| Armor: | Iron plates |

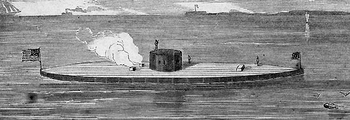

USS Monitor was the first ironclad warship commissioned by the United States Navy. She is most famous for her participation in the first-ever naval battle between two ironclad warships, the Battle of Hampton Roads on 9 March 1862, during the American Civil War, in which Monitor fought the ironclad CSS Virginia of the Confederate States Navy. Monitor was the first in a long line of Monitor-type U.S. warships and the term "monitor" describes a broad class of craft.

Ironclads were only a recent innovation, started with the floating ironclad batteries used in the Crimean War and the 1859 French battleship La Gloire. Afterwards, the design of ships and the nature of naval warfare changed dramatically.

Contents |

Construction

In response to news about construction of the CSS Virginia, Gideon Welles, the secretary of the United States Navy, decided that the Union would need an ironclad. Wells proposed to Congress the idea of there being a board composed of experts on ironclad ships. He was granted the authority to create this board a month later.[1]

The Ironclad Board was composed of three senior naval officers: Commodore Hiram Paulding, Commodore Joseph Smith, and Commander Charles Henry Davis. Welles put advertisements in Northern newspapers asking people to submit their designs for ironclads. The board initially chose two designs out of the 17 that were submitted.[2] These ships were the USS Galena and the USS New Ironsides.

Cornelius Bushnell, the designer of the Galena, went to New York City to have his design approved by the Swedish-born inventor John Ericsson. Ericsson, after assuring Bushnell that the Galena would be stable, brought out one of his own designs: a cardboard model of the USS Monitor. Bushnell immediately knew that Ericsson's ship was far superior to his own. Bushnell showed Ericsson's design to Welles, who arranged a meeting for Bushnell with the Ironclad Board.

Design

Designed by the Swedish engineer John Ericsson, Monitor was described as a "cheesebox on a raft,"[3] consisting of a heavy round revolving iron gun turret on the deck, housing two 11 in (280 mm) Dahlgren guns, paired side by side. The original design used a system of heavy metal shutters to protect the gun ports while reloading. However, the operation of the shutters proved so cumbersome, the gun crews simply rotated the turret away from potential hostile fire to reload. Further, the momentum of the rotating turret proved to be so great that a system for stopping the turret to fire the guns was implemented on later models of ships in the Monitor class. The crew of Monitor solved the turret momentum problem by firing the guns on the fly while the turret rotated past the target. While this procedure resulted in a substantial loss of accuracy, given the close range at which Monitor operated, the loss of accuracy was not critical.

The armored deck was barely above the waterline. Aside from the turret, a small boxy pilothouse, a detachable smokestack and a few fittings, the bulk of the ship was below the waterline to prevent damage from cannon fire. The turret comprised eight layers of 1 in (25 mm) plate, bolted together, with a ninth plate inside to act as a sound shield. A steam donkey engine turned the turret. The heavily armored deck extended beyond the waterproof hull, only 5⁄8 inches (16 mm) thick. The vulnerable parts of the ship were completely protected, as was proved during her battle with the Virginia during the Battle of Hampton Roads: the Virginia's shot bounced off of Monitor`s turret and deck, sometimes denting them but never breaching them. The only weak spot proved to be the pilothouse, both due to its location relative to the turret (poor aim on the part of Monitor`s gunners would cause them to strike their own pilothouse) and in or near its viewing slot, which, with one of the iron beams that reinforced the pilothouse was smashed by an exploding shell.[4]

Monitor's hull was built at the Continental Iron Works in the Greenpoint section of Brooklyn, New York, and the ship was launched there on 30 January 1862. The steam engines and machinery were constructed at the DeLamater Iron Works in Manhattan where 13th Street meets the Hudson River[5] There is a statue in Monsignor McGolrick park in Greenpoint, facing Monitor Street, commemorating the ship.

Monitor was innovative in construction technique as well as design. Parts were forged in nine foundries and brought together to build the ship; the whole process took less than 120 days. Portions of the heavy iron armor plating for the vessel were made at a forge in Clintonville, New York. In addition to the "cheesebox", its rotating turret, Monitor was also fitted with Ericsson's novel marine screw, whose efficiency and reliability allowed the warship to be one of the first to rely exclusively upon steam propulsion. Monitor had an unusually low freeboard, with the pilothouse and turret being the only permanent protrusions from the deck. Though this low freeboard greatly reduced the Monitor's vulnerability to gunfire compared to other naval vessels of the day, it also greatly reduced the ship's seakeeping capabilities.

Although John Ericsson was the designer of the ship itself, Saratoga Springs resident Theodore Timby is credited with the design of the revolving gun turret.[6] After showing his 21-foot (6.4 m) model to officials at the White House, a naval commission recommended Ericsson's ironclad be built with Timby's turret. Timby was paid a $13,500 commission for his contribution.[7] This is equivalent to $296,010 in present day terms.[8]

Monitor was also noteworthy for her social architecture. Unlike other ships of the time, in which common sailors slept near the bow, with those of increasingly higher rank being found as one worked back to the captain's cabin in the stern, on the Monitor it was the captain's cabin that appeard in the bow, followed by his officers and then the berth deck, where the junior officers, engineers, and sailors slept. Furthest aft were found the boilers and engines.[9]

Battle of Hampton Roads

On March 8, 1862, CSS Virginia attacked the Union blockading squadron in Hampton Roads, Virginia, destroying Cumberland and Congress. Early in the battle, Minnesota ran aground while attempting to engage the Virginia, and she remained stranded throughout the battle. Virginia, however, was unable to attack Minnesota before daylight faded.

That night, Monitor — under command of Lieutenant John L. Worden — arrived from Brooklyn after a harrowing trip under tow. When Virginia returned the next day to finish off Minnesota and the rest of the blockaders, Monitor moved out to stop her. The ironclads fought at close range for about four hours, neither one sinking or seriously damaging the other. At one point, Virginia attempted to ram, but she only struck Monitor with a glancing blow that did no damage. It did, however, aggravate the damage done to Virginia's bow when she previously rammed Cumberland. Monitor was also unable to do significant damage to Virginia, possibly due to the fact that her guns were firing with reduced charges.

Towards the end of the engagement, Virginia was able to hit Monitor's pilothouse. Lt. Worden, blinded by shell fragments and gunpowder residue from the explosion, ordered Monitor to sheer off into shallow water. The command passed to the executive officer, Samuel Greene, who assessed the damage and ordered Monitor to turn around back into the battle.

Virginia, seeing Monitor turn away, turned her attention back to Minnesota. The falling tide, however, prevented her from getting close to the stranded warship. After an informal war council with his officers, Virginia's captain decided to return to Norfolk to repairs. Monitor arrived back on the scene as Virginia was leaving. Greene, under orders to protect Minnesota, did not pursue.

Tactically, the battle between these two ships was a draw, though it could be argued that Virginia did slightly more damage to Monitor than Monitor did to Virginia. Monitor did successfully defend Minnesota and the rest of the U.S. fleet while Virginia was unable to complete the destruction she started the previous day. Strategically, nothing had immediately changed: The Federals still controlled Hampton Roads and the Confederates still held several rivers and Norfolk.[10]

Events after the battle

Both Union and Confederates came up with plans for defeating the other’s ironclad. Oddly, these did not depend on their own ironclads. The Union Navy chartered a large ship (the sidewheeler Vanderbilt) as a ram, provided Virginia steamed far enough out into Hampton Roads. The Confederate Navy made plans to swarm aboard and capture Monitor using the four gunboats of the James River Squadron. On 11 April, Virginia steamed out to Sewell’s Point at the southeast edge of Hampton Roads in a challenge to Monitor.

In an attempt to lure Monitor closer to where she could be boarded, Virginia stood out into the Roads and almost over to Newport News. However, Monitor stayed near Fort Monroe, ready to fight if Virginia came to attack the Federal force which had congregated there. Furthermore, Vanderbilt would be in a position to ram Virginia if she approached the fort. Virginia did not take the bait. In a further attempt to entice Monitor closer to the Confederate side so she could be boarded, the James River Squadron moved in and captured three merchant ships, the brigs Marcus and Sabout, and the schooner Catherine T. Dix. These had been grounded and abandoned when they sighted Virginia entering the Roads. Their flags were then hoisted "Union-side down" to taunt Monitor into a fight as they were towed back to Norfolk. In the end both sides had failed to lure the other out for a fight on their terms.

A second meeting occurred on 8 May, when Virginia came out while Monitor and four other Federal ships bombarded Confederate batteries at Sewell’s Point. The Federal ships retired slowly to Fort Monroe, hoping to lure Virginia into the Roads. She did not follow, however, and after firing a gun to windward as a sign of contempt, anchored off Sewell’s Point. However, she was forced to scuttle when Confederate forces abandoned Norfolk three days later.

After the destruction of Virginia, Monitor was free to assist McClellan's campaign against Richmond. On 15 May 1862, the ironclad and four other gunboats steamed up the James River and engaged Confederate batteries at Drewry's Bluff. Monitor's guns, however, could not elevate sufficiently to engage the batteries at close range, and the other gunboats were unable to overcome the fortifications on their own. The engagement ended when the Union fleet retired after four hours of bombardment.[5][10]

Loss at sea

While the design of Monitor was well-suited for river combat, her low freeboard and heavy turret made her highly unseaworthy in rough waters. This feature probably led to the early loss of the original Monitor, which foundered during a heavy storm. Swamped by high waves while under tow by Rhode Island, she sank on 31 December 1862 off Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. 16 of the 62 crewmen were lost in the storm.

The name Monitor was given to the troop carrier USS Monitor (LSV-5), commissioned late in World War II. She served primarily in the Pacific theater, and was later scrapped.

Rediscovery

In 1973, the wreck of the ironclad Monitor was located on the floor of the Atlantic Ocean about 16 nautical miles southeast of Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. The wreck site was designated as the first U.S. marine sanctuary. Monitor National Marine Sanctuary is the only one of the thirteen national marine sanctuaries created to protect a cultural resource, rather than a natural resource.

In 1986, Monitor was designated a National Historic Landmark. It is one of only four accessible monitor vessels in the world, the others being the Australian vessel HMVS Cerberus, and the wreck of the Norwegian KNM Thor, which lies at about 25 ft (7.6 m) off Verdens Ende in Vestfold county, Norway, and the British vessel Hellman.

The U.S. Navy interest in raising the entire ship ended in 1978 when Willard F. Searle, Jr. calculated the cost and possible damage expected from the operation.[11] However in 1998 the warship's propeller was raised to the surface.[11] On July 16, 2001, divers from the Monitor National Marine Sanctuary and the US Navy brought to the surface the 30-metric-ton (30-long-ton) steam engine. Due to the depth of the wreck, the divers utilized surface supplied diving techniques while breathing heliox.[12] In August 2002, after 41 days of work, the revolutionary revolving gun turret was recovered by the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and a team of U.S. Navy divers. Before removing the turret, divers discovered the remains of two trapped crewmen. The remains of these sailors, who died while on duty, are at the Joint POW-MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) at Hickam Air Force Base, Hawaii, awaiting positive identification.

The site is now under the supervision of NOAA. Many artifacts from Monitor, including her turret, cannon, propeller, anchor, engine and some personal effects of the crew, have been conserved and are on display at the Mariners' Museum of Newport News, Virginia. Artifact recovery from the site has become paramount, as the wreck has become unstable and will decay over the next several decades; this fate also awaits many other commonly-dived wrecks of iron and steel ships, such as Titanic.

Campaign to honor Monitor

The Cleveland Civil War Roundtable is mounting a grassroots campaign to persuade the United States Congress and the Navy to name a Virginia class submarine after Monitor. Despite the enduring fame of the original, innovative ironclad, there has not been a warship named Monitor listed in the Naval Vessel Register since 1961.

The Monitor-class warship

Monitor became the prototype for the monitor class of warship. Many more were built, including river monitors and deep-sea monitors, and they played key roles in Civil War battles on the Mississippi and James rivers. Some had two or even three turrets, and later monitors had improved seaworthiness.

Just three months after the famous Battle of Hampton Roads, the design was offered to Sweden, and in 1865 the first Swedish monitor was being built at Motala Wharf in Norrköping; she was named John Ericsson in honor of the engineer. She was followed by 14 more monitors. One of them, Sölve, is still preserved at the marine museum in Gothenburg.

Prior to the Vietnam War, the last U.S. Navy monitor-class warship was stricken from the Navy List in 1937. In 1966, Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara[13] reactivated the US Navy's Brown Water Navy, which would ultimately commission 24 US Navy Monitors for riverine operations in South Vietnam. Upon the deactivation of the Navy's Brown Water fleet in 1970 in Vietnam, the last U.S. Navy Monitor-class warships were stricken from the Naval Registry. However, the generic term is still often used to describe an armored, heavily gunned river patrol vessel.

See also

- Battle of Hampton Roads

- CSS Virginia

- Ironclad warship

- John Ericsson

- Jefferson Furnace, where much of the iron used for the ship was produced.

- Cornelius H. DeLamater who owned the Iron Works where the boilers and machinery were constructed.

References

- ↑ Time-Life Books "The Blockade: Runners and Raiders" Pg. 51

- ↑ http://www.mariner.org/uss-monitor-center/report-iron-clad-vessels

- ↑ Axelrod, Alan (2003). The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Civil War. Alpha Books. pp. 448 pages. ISBN 9781592571321. http://books.google.com/books?id=vOfXZ1-U-XMC&pg=PA107&lpg=PA107&dq=%22cheesebox+on+a+raft%22&source=web&ots=VB3YRDdUYz&sig=3Lzj16raYJI4lDF1IF8qKtALtyA&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=10&ct=result#PPA108,M1.

- ↑ Marvel, William (Editor), The Monitor Chronicles. Simon and Schuster, New York. 2000. pp. 28, 29.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Nelson, James L (2005). Reign of Iron: The Story of the First Battling Ironclads, the Monitor and the Merrimack. HarperCollins. pp. 400 pages. ISBN 9780060524043. http://books.google.com/books?id=d8XD-j--EVsC&pg=PA149&lpg=PA149&dq=Delamater+Iron+works+monitor&source=bl&ots=wb-P4Hew0q&sig=QH7EKP0z-BCtWFqpPHrrQlQNNkw&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=5&ct=result#PPA149,M1.

- ↑ Invented in Saratoga County

- ↑ Brooklyn Daily Eagle

- ↑ Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–2008. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved December 7, 2010.

- ↑ Marvel, William (Editor), The Monitor Chronicles. Simon and Schuster, New York. 2000. p.17.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Davis, William C. (1975). Duel Between the First Ironclads. Doubleday & Company, NY. pp. 199 pages.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Erickson, Mark St. John (1998). "Sands of time: Part 5 of 5". Newport News, Va., Daily Press. http://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/dp-news-ussmonitor98_5,0,3504569.story?page=2. Retrieved 2009-04-15.

- ↑ Southerland DG; Davidson DL (2002-10-29). Electronic diving data collection during Monitor expedition 2001.. 2. MTS/IEEE. pp. 908–912. http://archive.rubicon-foundation.org/7970. Retrieved 2009-03-01.

- ↑ Carrico p. 11

Bibliography

- Military Heritage magazine did a feature on the USS Merrimack (CSS Virginia), the USS Monitor, and the Battle at Hampton Roads (Keith Milton, Military Heritage, December 2001, Volume 3, No. 3, pp. 38 to 45 and p. 97).

- Gott, Kendall D., Where the South Lost the War: An Analysis of the Fort Henry—Fort Donelson Campaign, February 1862, Stackpole books, 2003, ISBN 0-8117-0049-6.

- Saratoga County History: Invented in Saratoga County

- The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, various issues, 1902

Publications

- Bennett, The Monitor and the Navy under Steam (Boston, 1900)

- Johnson and C. C. Buel (editors), Battles and Leaders of the Civil War volume i, (New York, 1887)

- Carrico, John M. Vietnam Ironclads; A Pictorial History of US Navy River Assault Craft, 1966-1970. (Brown Water Enterprises, 2007). ISBN 978-0-9794-2310-9.

- Mindell, War, Technology, and Experience aboard the USS Monitor (Baltimore, 2000)

- Wilson, Ironclads in Action (London, 1896)

- Hill, Twenty-six Historic Ships (New York, 1903)

- William C. Davis, Duel Between the First Ironclads,(New York, 1975)

External links

- The Monitor Center at the Mariners' Museum, Newport News, Virginia

- HNSA Ship Page: USS Monitor

- SF Gate describing the Monitor and depth charging

- Seattle Pilot mentioning the depth charging of the Monitor

- USS Monitor (1862–1862) -- Construction

- Museum of the Confederacy in Richmond, VA official website

- U.S. Naval History Center

- Monitor in the news – "Monitor turret raised from ocean"

- Online exhibition about Monitor

- Hampton Roads Naval Museum

- Roads to the Future – I-664 Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge Tunnel

- High resolution photo taken on deck of USS Monitor

- Video of wreck site from the 2008 USS Monitor expedition .wmv download

- Video of model vibrating-lever engine of USS Monitor, www.youtube.com.

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||