United States Army Air Service

| Air Service, United States Army | |

|---|---|

"Prop and Wings" branch insignia of the Air Service |

|

| Active | May 24, 1918–July 2, 1926 |

| Country | United States of America |

| Branch | United States Army |

| Size | 195,024 men, 7,900 aircraft (1918) 9,954 men, 1,451 aircraft (1926) |

The United States Army Air Service (officially the Air Service, United States Army[1]) was a forerunner of the United States Air Force. It was established on May 24, 1918, after U.S. entry into World War I, replacing the Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps which had been the nation's air force from 1914 to 1918.

Although the Air Service was recognized by the Department of War on May 24, 1918, no Director of Air Service was appointed until August 28, when President Woodrow Wilson made John D. Ryan a Second Assistant Secretary of War and civilian Director of Air Service. After World War I, the Air Service was again directed by a military officer and remained so until replaced by the United States Army Air Corps on July 1, 1926.

The Air Service was the first form of the air force to have both its own unique organizational structure and identity. Prior to May 1918 its permanent personnel were part of the Signal Corps and its pilots on temporary assignment from other branches of the Army. Between May 1918 and July 1920, enlisted men were assigned to and new officers commissioned in the Air Service as either war-mobilized National Army or United States Army (Regulars). After July 1, 1920, all personnel retained by the Army were designated members of the Air Service, with officers who had been previously commissioned in the Signal Corps or the Signal Officers Reserve Corps (S.O.R.C.) receiving new commissions in the Air Service branch.

Lineage of the United States Air Force

- Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps August 1, 1907–July 18, 1914

- Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps July 18, 1914–May 20, 1918

- Division of Military Aeronautics May 20, 1918–May 24, 1918

- Air Service, United States Army May 24, 1918–July 2, 1926

- United States Army Air Corps July 2, 1926–June 20, 1941

- United States Army Air Forces June 20, 1941–September 18, 1947

- United States Air Force September 18, 1947–present

Creation of the Air Service

See main articles: Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps and Division of Military Aeronautics

Although Congress had vastly increased the appropriations for the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps in 1916, it had also tabled a bill proposing an aviation department incorporating all aspects of military aviation, the first ever introduced to create a separate aviation service. The declaration of war against Germany on April 6, 1917, putting the United States in World War I, came too quickly to solve emerging engineering and production problems, and the reorganization of the Aviation Section had been inadequate in resolving problems in training, leaving the United States totally unprepared to fight an air war in Europe.

The administration of President Woodrow Wilson, through its Council of National Defense, created an advisory Aircraft Production Board in May 1917, consisting of members of the Army, Navy, and industry, to study the Europeans' experience in aircraft production and the standardization of aircraft parts.[1] The United States Congress responded to the problems by considering two new bills to create a "Department of Aeronautics" consolidating all aviation activities, including aircraft production, into a single department, and passed a series of legislation in the next three months that appropriated huge sums for development of military aviation, including the largest single appropriation for a single purpose to that time, $640 million in the Aviation Act (40 Stat. 243), passed July 24, 1917.[1]

Both the Department of War and the Department of the Navy opposed the creation of a separate air department, and on October 1, 1917, Congress instead legalized the existence of the APB and changed its name to the "Aircraft Board", transferring its functions from the Council of National Defense to the secretaries of War and the Navy.[1] Even so, the Aircraft Board in practice had little control over procurement contracts and functioned mostly as an information clearinghouse between the various involved business, governmental, and military entities. Moreover, the airplane of World War I was not suitable to the mass production methods of the automotive industry and the priority of mass producing spare parts was neglected. Though individual areas within the aviation industry responded well, the industry as a whole failed. Efforts to mass produce European aircraft under license largely failed.

As a result, the board came under severe criticism for failure to meet goals or its own claims of aircraft production, followed by a highly-publicized personal investigation by Gutzon Borglum, a harshly vocal critic of the board. Borglum had exchanged letters with President Wilson, a personal friend, from which he assumed an appointment to investigate had been authorized, which the administration soon denied.[2] Both the U.S. Senate and the Department of Justice began investigations into possible fraudulent dealings. President Wilson also acted by appointing a Director of Aircraft Production on April 28, 1918, and creating a Division of Military Aeronautics (DMA) under Brigadier General William L. Kenley, to separate supervision of aviation from the duties of the Chief Signal Officer.[1] However, before this took effect, Wilson used a provision of the Overman Act of May 20, 1918, to issue Executive Order No. 2862 that removed the DMA entirely from the Signal Corps (reporting directly to the Secretary of War), and assigned it the function of procuring and training a combat force. In addition, the executive order created a Bureau of Aircraft Production (BAP) as a separate executive bureau to provide the aircraft needed.[1][3]

This arrangement lasted only four days, when the War Department issued General Order No. 51 creating the Air Service, United States Army to consolidate the two agencies under a single director.[4] (The term "Air Service" had been in use in France since June 13, 1917, to describe the function of aviation units attached to the American Expeditionary Force.) However, it delayed the appointment of a director as long as the BAP operated as a separate bureau. In August, the Senate completed its investigation of the Air Board, and while it found no criminal culpability, it reported that massive waste and delay in production had occurred. As a result, the Director of Aircraft Production (who was also chairman of the Aircraft Board), John D. Ryan, was appointed to the vacant position of Second Assistant Secretary of War and named Director of Air Service, in charge of both the BAP and DMA.[1] The Department of Justice report followed two months later and also blamed the delays on administrative and organizational deficiencies in the Aviation Section. Ryan's appointment came too late for any effective consolidation of both agencies.

Following the Armistice, Ryan resigned on November 27, leaving both the BAP and DMA, as well as the original Aircraft Board, leaderless. Maj. Gen. Charles Menoher was appointed the new Director of Air Service on January 2, 1919, but the patchwork nature of laws and executive orders that had created the various parts of the Air Service prevented him from exercising all their legal powers. President Wilson issued a new executive order in March 1919 dissolving the Aircraft Board and consolidating all powers conferred into a single executive, the Director of Air Service.[5]

By November 11, 1918, the Air Service both overseas and domestically had 195,024 personnel (20,568 officers; 174,456 enlisted men) and 7,900 aircraft,[6] constituting five per cent of the United States Army.[7] With an aviation cadet program modeled on Canada's, the Air Service commissioned over 17,000 as reserve officers. Using variants of the Curtiss Jenny, 27 flying training centers graduated nearly 8,000 pilots, and 1,600 more came from foreign schools in Great Britain, France, and Italy. 10,000 mechanics were trained to service the American aircraft fleet. Of aircraft manufactured in America, the de Havilland DH-4 (3,400) was the most numerous, although only 1,200 were shipped overseas, most used in observation units.

Assigned overseas in the American Expeditionary Force, the air arm totalled 78,507 (7,738 officers and 70,769 enlisted men) at the armistice. Of this total, 58,090 served in France; 20,075 in England; and 342 in Italy. Balloon troops made up approximately 17,000 of the Air Service, with 6,811 in the dangerous duty of spotting for the artillery at the front.[8]

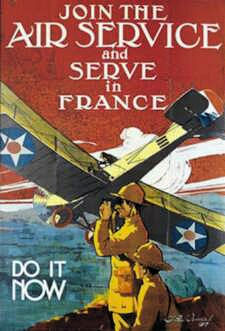

Air Service World War I posters

|

|

|

|

|

Air Service of the AEF

Organization

During the first year of U.S. participation in World War I, aviation units had been created and deployed without organization. Upon his arrival in France in June 1917, Pershing met with Lieutenant Colonel Billy Mitchell, who had been sent to Europe in March 1917 as an observer, and arrived in Paris just four days after the United States declared war.[9] Mitchell had established a "headquarters" for the American "air service" and so advised Pershing that it was ready to proceed with any project Pershing might require.[10] Pershing's aviation officer, Major Townsend Dodd, first used the term "Air Service" in a memo to the chief of staff of the AEF on 20 June 1917.[11] The first official use of the term was in AEF General Order No. 8, 5 July 1917, in tables detailing staff organization and duties.[12] The term became commonplace, but units organized into "air services" down to the corps level did not occur until May 1918.[13]

Five days after the formation of the Army Air Service, separating it from the Signal Corps, General John J. Pershing, commanding the American Expeditionary Force (AEF), duplicated the action in Europe by creating the "Air Service of the AEF" and placing it in charge of all U.S. aviation units, personnel, and equipment in France. As Chief of Air Service, AEF, he chose a West Point classmate and non-aviator, Major General Mason Patrick. Air Service staff planning had been inefficient, with considerable friction between its members and those of Pershing's General Staff. Aircraft and unit totals lagged far behind those promised in 1917. Considerable house-cleaning of the existing staff coincided with Patrick's appointment, bringing in experienced staff officers to administrate and tightening up lines of communication.

General Pershing had at first called for creation of 260 U.S. air combat squadrons, but slowness of the buildup reduced that to 202 on August 17, 1918. In Pershing's view, the two functions of the AEF's Air Service were to repel German aircraft and conduct observation of enemy movements. The heart of the force was its 101 observation squadrons (52 corps observation and 49 army observation), to be distributed to three armies and 16 corps. In addition, 60 pursuit squadrons, 27 night-bombardment squadrons, and 14 day-bombardment squadrons were to conduct supporting operations.[14]

Without the time or infrastructure in the United States to equip units to send overseas using aircraft designed and built in the U.S., the AEF Air Service ordered Allied aircraft designs already in service with the French and British air services. On August 30, 1917, the American and French governments agreed to a contract in which France would provide the Air Service AEF, with 1,500 Breguet 14 B.2 bombers and reconnaissance planes; 2,000 SPAD XIII fighters; and 1,500 Nieuport 28 pursuits.

The primary aircraft employed were the SPAD XIII (877 combat sorties), Nieuport 28 (181), and SPAD VII (103) as pursuit aircraft, the DeHaviland DH-4 (696) and Breguet 14 (87) for daylight bombing, and the DH-4 and Salmson 2 A.2 (557 sorties) for observation and photo reconnaissance. The SE-5 operated as the main trainer for the Air Service. Balloon companies operated the French Caquot Type R hydrogen-filled observation balloon, with one balloon per company.

Operations

The first U.S. aviation squadron to reach France was the 1st Aero Squadron, an observation unit, which sailed from New York in August 1917 and arrived at Le Havre on September 3. A member of the squadron, Stephen W. Thompson, on February 5, 1918, achieved the first aerial victory by the U. S. military. As other squadrons were organized at home, they too were sent overseas, where they continued their training. It was February 18, 1918, before any U.S. squadron entered combat (the 103rd Aero Squadron, a pursuit unit flying with French forces and composed largely of former members of the Lafayette Escadrille). By the beginning of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive the Air Service AEF consisted of 32 squadrons (15 pursuit, 13 observation, and 4 bombing) at the front,[15] while by November 11, 1918, 45 squadrons (20 pursuit,[16] 18 observation,[17] and 7 bombardment[18]) had been assembled for combat. During the war, these squadrons played important roles in the Third Battle of the Aisne, the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, and the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. Several units, including the 94th Aero Squadron, Captain Eddie Rickenbacker commanding, and the 27th Aero Squadron, which had "balloon buster" First Lieutenant Frank Luke as one of its pilots, achieved distinguished records in combat and became part of the future United States Army Air Corps.

Observation planes often operated individually, as did pursuit pilots to attack a balloon or to meet the enemy in a dogfight. However the tendency was toward formation flying, for pursuit as well as for bombardment operations, as a defensive tactic. The dispersal of squadrons among the army ground units (each corps and division had an observation squadron attached) made coordination of air activities difficult, so that squadrons were organized by functions into groups, the first of these being the 1st Corps Observation Group, organized in April 1918. On May 5, 1918, the 1st Pursuit Group was formed, and by the armistice the AEF had 14 heavier-than-air groups (7 observation, 5 pursuit, and 2 bombardment).[19] Of these 14 groups, only the 1st Pursuit and 1st Day Bombardment Groups would have their lineage continued into the post-war Air Service.

In July 1918, the AEF organized its first wing, the 1st Pursuit Wing, made up of the 2d Pursuit, 3rd Pursuit, and 1st Day Bombardment Groups. Each Army and Corps echelon of the ground forces had a chief of air service designated to direct operations. The Air Service, First Army was activated August 26, 1918, marking the commencement of large scale coordinated U.S. air operations. Col. Benjamin Foulois was named chief of the First Army Air Service over Col. Billy Mitchell, who had been directing air operations as chief of the I Corps Air Service since March, but Foulois voluntarily relinquished his post to Mitchell and became one of the two assistant chiefs of Air Service AEF, at Tours in charge of personnel and training. Mitchell went on to become a brigadier general and chief of the Army Group Air Service in mid-October 1918, succeeded at First Army by Col. Thomas Milling. The Air Service, Second Army was activated in November just before the armistice, and the Air Service, Third Army was created immediately after the armistice to provide aviation support to the army of occupation.

Mitchell and Foulois were advocates of the formation of an "air force" to centralize control over military aviation. In the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, commencing September 12, 1918, the American and French offensive against the German salient was supported by 1,481 airplanes directed by Mitchell, totalling 24 Air Service, 58 French Aéronautique Militaire, and three Royal Air Force squadrons in coordinated operations. Observation and pursuit planes supported ground forces, while the other two-thirds of the aerial force bombed and strafed behind enemy lines. Later, during the Meuse-Argonne offensive, Mitchell employed a smaller concentration of airpower, nearly all American this time, to keep the German army on the defensive.

Army of occupation duties

Immediately after the armistice, the AEF formed the Third United States Army to march immediately into Germany, occupy the Coblenz area, and be prepared to resume combat if peace treaty negotiations failed. Three corps were formed from seven of the Army's most experienced divisions,[20] and Brig. Gen. Mitchell was appointed to command the Air Service, Third Army, on November 14, 1918.[21]

As with the ground forces, the most veteran units of the Air Service were selected to form the new Air Service. A pursuit unit, the 94th "Hat in the Ring" Aero Squadron; a day bombardment squadron, the 166th; and four observation squadrons (1st, 12th, 88th, and 9th Night) were initially assigned.[22] The demobilization of the AEF accelerated in December and January, and all but two of these squadrons returned to the United States. Gen. Mitchell was replaced in January as commander of the Third Army Air Service by Col. Harold Fowler, a combat veteran of the Royal Flying Corps and former commander of the American 17th Pursuit Squadron.

By March 1919 the U.S. Second Army in France had also closed down. Its former air units were transferred to the Third Army Air Service in Germany, which at its maximum consisted of the:

- 5th Pursuit Group (41st, 138th, 141st, and 605th Aero Squadrons) at Coblenz, the

- 3rd Corps Observation Group (1st, 24th, and 258th A.S.) at Weißenthurm, the

- 4th Corps Observation Group (85th and 278th A.S. only, its other squadrons sent home before assignment) at Sinzig, and the

- 7th Corps Observation Group (9th, 88th, and 186th A.S.) at Trier.

The Third Army and its air service were inactivated in July 1919 after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles.[23]

Statistical summary, World War I

"Though the casualties in the air force were small compared with the total strength, the casualty rate of the flying personnel at the front was somewhat above the Artillery and Infantry rates... The results of allied and American experience at the front indicate that two aviators lose their lives in accidents for each aviator killed in battle.[15]

The 740 airplanes[24] equipping the AEF on November 11, 1918, were approximately 10% of the total aircraft strength of the Allied forces.[25] The 45 squadrons in the Zone of Advance had 767 pilots, 481 observers, and 23 aerial gunners, covering 137 kilometers of front from Pont-à-Mousson to Sedan. 35 balloon companies also deployed in France, 17 at the front and six en route to the Second Army, and made 1,642 combat ascensions. 13 photographic sections were assigned to observation squadrons. 43 flying training, air park (supply), depot, and construction squadrons supported the air services.[25] In all, 211 squadrons of all types trained in Great Britain, with 71 arriving in France before the Armistice.[26] A major air depot at Colombey-les-Belles; three other maintenance depots at Behonne, LaTrecey, and Vinets; four supply depots at Clichy, Romorantin, Tours, and Is-sur-Tille; and 17 air park squadrons maintained the combat and training forces.[27] At its peak establishment in November 1918, the Air Service was based at 31 stations in the Service of Supply and 78 aerodromes in the Zone of Advance.[28]

A large training establishment was also set up in France. The Air Service Concentration Barracks at Saint-Maixent received all Air Service troops arriving in France, distributing them to 26 training centers and schools throughout central and western France.[29] Flying training schools, equipped with 2,948 airplanes, supplied 1,674 fully-trained pilots and 851 observers to the Air Service, with 1,402 pilots and 769 observers serving at the front. The observers trained in France included 825 artillery officers from the infantry divisions who volunteered to fill a critical shortage in 1918.[30] After the Armistice, the schools graduated 675 additional pilots and 357 observers to serve with the Third Army Air Service in the Army of Occupation.[31] The 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun provided 766 pursuit pilots.[32] 169 students and 49 instructors died in training accidents.[33] Balloon candidates made 4,224 practice ascensions while training.

The Air Service conducted 150 bombing missions, the longest 160 miles behind German lines, and dropped 138 tons (125 kg) of bombs. Its squadrons had 756 confirmed destruction of German aircraft and 76 German balloons destroyed, creating 71 Air Service aces.[34] Air Service combat losses were 289 airplanes and 48 balloons (35 shot by German fighters, 12 by antiaircraft guns, and 1 that drifted across the lines), with 235 airmen killed in action, 130 wounded, 145 captured, and 654 Air Service members of all ranks dead of illness or accidents.[35] Air Service personnel were awarded 611 decorations in combat, including 4 Medals of Honor and 312 Distinguished Service Crosses (54 were oak leaf clusters). 210 decorations were awarded to aviators by France, 22 by Great Britain, and 69 by other nations.[36]

Air Service of the AEF, 11 November 1918

SOURCES: Order of battle and commanders, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, Vol. I, pp. 391–392; locations and aircraft Combat Squadrons of the Air Force, World War II under individual unit entries

Chief of Air Service, AEF - Maj.Gen. Mason Patrick (Chaumont)

- Chief of Air Service, Group of Armies - Brig. Gen. William L. Mitchell

Air Service, First Army

Col. Thomas D. Milling, (Souilly)

- 1st Pursuit Group - (Rembercourt, Maj. Harold E. Hartney)

- 27th, 94th, 95th, & 147th Aero Squadrons (Spad XIII)

- 1st Pursuit Wing - (Chaumont-sur-Aire, Maj. Burt M. Atkinson)

- 2d Pursuit Group - (Souilly, Maj. Davenport Johnson)

- 13th, 22d, 99th, & 139th Aero Squadrons (Spad S.XIII)

- 3d Pursuit Group - (Foucaucourt, Maj. William K. Thaw)

- 28th, 93d, 103d Aero Squadron, & 213th Aero Squadrons (Spad XIII)

- 1st Day Bombardment Group - (Maulan, Maj. James L. Dunsworth)

- 11th, 20th, 166th (DH-4B) & 96th (Breguet 14 B2) Aero Squadrons

- 2d Pursuit Group - (Souilly, Maj. Davenport Johnson)

- 155th Aero Squadron (night bombardment) - (Belrain, Sopwith FE-2b)

- First Army Observation Group - (Vavincourt, Capt. Harry T. Wood)

- 9th Aero Squadron (night reconnaissance) - (DH-4B, FE-2b)

- 24th Aero Squadron - (Salmson 2 A2)

- 91st Aero Squadrons (Salmson 2 A2)

- 186th Aero Squadron (Lemmes, Salmson 2 A2)

- First Army Balloon Group - (Maj. John Paegelow)

- 11th (Fontaines) & 43d (Fossé) Balloon Companies

- Corps Observation Wing - (Rampont, Maj. Melvin A. Hall)

- Air Service, I Corps - (Chéhéry, Capt. Oliver P. Echols)

- 1st Corps Observation Group - (Julvécourt)

- Air Service, I Corps - (Chéhéry, Capt. Oliver P. Echols)

-

-

- 1st Aero Squadron - (Salmson 2 A2)

- 12th Aero Squadron - (Salmson 2 A2)

- 50th Aero Squadron - (Clermont-en-Argonne, DH-4B)

- 88th Aero Squadron - (AR type, Sopworth 1, Salmson 2 A2)

- 90th Aero Squadron - (Sopworth 1, Salmson 2 A2, Spad XI)

- N.211 Escadrille, Aéronautique Militaire (Clermont-en-Argonne)

-

-

-

- 1st Corps Balloon Group - (Chéhéry)

- 1st (Auzéville), 2d (Les Petites-Armoises), & 5th (La Besace) Balloon Companies

- 1st Corps Balloon Group - (Chéhéry)

- Air Service, III Corps - (Dun-sur-Meuse, Maj. Joseph C. Morrow)

- 3d Corps Observation Group - (Bethelainville, Capt. Kenneth P. Littauer)

-

-

-

- 88th Aero Squadron (Salmson 2 A2)

- 90th Aero Squadrons (Salmson 2 A2)

- N.219 & N.229 Escadrille, Aéronautique Militaire

-

-

-

- 3d Corps Balloon Group - (Dun-sur-Meuse)

- 3d (Belrupt), 4th (Vilosnes-sur-Meuse), 9th (Consenvoye), & 42d (Villers-devant-Dun) Balloon Companies

- 3d Corps Balloon Group - (Dun-sur-Meuse)

- Air Service, V Corps - (Nouart, Maj. Martin F. Scanlon)

- 5th Corps Observation Group - (Parois, Capt. Stephen H. Noyes)

-

-

-

- 99th Aero Squadron (Salmson 2 A2)

- 104th Aero Squadron (Salmson 2 A2)

- N.214 & N.215 Escadrille, Aéronautique Militaire

-

-

-

- 5th Corps Balloon Group - (Nouart, Capt. Alvin C. Rois)

- 6th (Brabant-sur-Meuse), 7th (Tailly), 8th (Nouart), & 12th (Buzancy) Balloon Companies

- 5th Corps Balloon Group - (Nouart, Capt. Alvin C. Rois)

-

Air Service, Second Army

Col. Frank Lahm, (Toul)

- Balloons Wing - (Toul, Maj. John H. Jouett)

- N.20 and N.52 Balloon Companies, Aéronautique Militaire

- 4th Pursuit Group - (Toul, Maj. Charles J. Biddle)

- 17th, 25th, 141st, & 148th Aero Squadrons (mostly Spad XIII, with S.E.5a for 25th Aero Squadron)

- 5th Pursuit Group - (Lay-Saint-Remy, Capt. Dudley L. Hill)

- 41st, 138th, & 638th Aero Squadrons (forming)

- 2nd Day Bombardment Group - (Ourches, Maj. George E. A. Reinberg)

- 100th Aero Squadron & 163d Aero Squadrons (DH-4B)

- Second Army Observation Wing - (Toul, Lt.Col. John H. Reynolds)

- Second Army Observation Group - (Major C. Delaney, attached from French Third Army)

-

- N.28, N.47, and N.277 Escadrille

-

- Air Service, IV Corps - (Toul, Maj. Harry B. Anderson)

- 4th Corps Observation Group - (Toul)

- Air Service, IV Corps - (Toul, Maj. Harry B. Anderson)

-

-

- 8th Aero Squadron - (Salmson 2.A2)

- 135th Aero Squadron - (DH-4B)

- 168th Aero Squadron - (DH-4B)

- 255th & 278th Aero Squadrons (designated for VII Corps) - (DH-4B)

-

-

-

- 4th Corps Balloon Group

- 15th, 18th, & 69th Balloon Companies

- 4th Corps Balloon Group

- Air Service, VI Corps - (Nancy, Maj. Joseph T. McNarney)

- 6th Corps Observation Group - (Saizerais, Capt. John G. Winant)

-

-

-

- 8th Aero Squadron - (Salmson 2.A2)

- 354th Aero Squadron - (DH-4B)

-

-

-

- 6th Corps Balloon Group

- 10th Balloon Company

- 6th Corps Balloon Group

-

Postwar reorganization of the Air Service

Executive order

In France the "Air Service" was a component of Pershing's American Expeditionary Force (AEF). In the United States the Chief Signal Officer was responsible for organizing, training, and equipping aviation units until May 20, 1918. At that time, the President separated aviation from the Signal Corps, creating a Bureau of Aircraft Production (BAP), to be responsible for aeronautical equipment, and a Division of Military Aeronautics (DMA), to be responsible for the training of personnel and aviation units. An Aircraft Engineering Department was set up within the BAP and a Technical Section within the DMA, both under military officers and having similar responsibilities. Both the BAP and the DMA were then placed under the administration of the newly-created Army Air Service on May 24, and formally merged into the air arm by Executive Order 3066 on March 19, 1919.

At the end of November 1918, the Air Service consisted of 185 flying, 44 construction, 114 supply, 11 replacement, and 150 spruce production squadrons; 86 balloon companies; six balloon group headquarters; 15 construction companies; 55 photographic sections; and a few miscellaneous units. Its personnel strength was 19,189 officers and 178,149 enlisted men. Its aircraft inventory consisted primarily of Curtiss JN-4 trainers, de Havilland DH-4B scout planes, SE-5 and Spad S.XIII fighters, and Martin MB-1 bombers.

Complete demobilization of the Air Service was accomplished within a year. By November 22, 1919, the Air Service had been reduced to one construction, one replacement, and 22 flying squadrons; 32 balloon companies; 15 photographic sections; and 1,168 officers and 8,428 enlisted men. The combat strength of the Air Service was only four pursuit and four bombardment squadrons. Although the leaders of the reorganized Air Service persuaded the General Staff to increase the combat strength to 20 squadrons by 1923, the balloon force was deactivated, including dirigibles, and personnel shrank even further, to just 880 officers. By July 1924, the Air Service inventory was 457 observation planes, 55 bombers, 78 pursuit planes, and 8 attack aircraft, with trainers to make the total number 754.

The Air Service replaced its wartime structure with the formation of six permanent groups in 1919, four of which were based in the United States (only two of which were combat groups) and two overseas. In 1920, a seventh group was formed to provide a headquarters for squadrons serving in the Philippines, and in 1922 an eighth group was created to replace one inactivated the year before. (The 8th Fighter Group was also designated on March 23, 1923, but not activated until 1931 as part of the Air Corps.)

1920 reorganization

With the passage of the Armed Forces Reorganization Act (41 Stat. 759 - June 4, 1920), the Air Service became a combatant arm of the Army, along with the Infantry, Cavalry, Field Artillery, Corps of Engineers, and Signal Corps. A Chief of Air Service was authorized with the rank of major general to replace the previous Director of Air Service, and an assistant chief created in the rank of brigadier general (from 1920 to 1925 this position was held by Brig.Gen. Billy Mitchell). The primary missions of the Air Service were observation and pursuit aviation, and its tactical squadrons in the United States were controlled by the commanders of nine corps areas created by the Act, primarily in support of the ground forces. The Chief of the Air Service retained command of training schools, depots, and support activities exempted from corps control.

The General Staff produced a mobilization plan in the 1920 reorganization that in the event of war would create an expeditionary force of six armies, 18 corps, and 54 divisions. Each army would have an Air Service attack wing (one attack and two pursuit groups) and an observation group, each corps and division would have an observation squadron, and a seventh attack wing-observation group would be reserved for the Expeditionary Force's general headquarters. A single bombardment group was planned, relegating bombardment to the most minor of roles. All aviation units would be under the command of ground officers at all levels. This structure provided the principles by which the Air Service and Air Corps operated until 1935.

The principal pursuit planes of the Air Service were the MB-3 (50 in inventory), the MB-3A (200 acquired 1920-23), and the Curtiss PW-8/P-1 Hawk (48 acquired in 1924-25). The only bomber ordered in quantity was the Martin NBS-1, the mass-produced version of the MB-2 bomber developed in 1920. Mitchell used the NBS-1 as the primary striking weapon during his demonstration in July 1921 off the Virginia coast that resulted in the sinking of the captured German battleship Ostfriesland.

Aeronautical development became the responsibility of the Technical Section, Air Service, created January 1, 1919, consolidating the Aircraft Engineering Department BAP, the Technical Section DMA, and the Testing Squadron at Wilbur Wright Field, which was renamed the Engineering Division on March 19 and relocated to McCook Field, Dayton, Ohio.

A formal training establishment was also created by the Air Service on February 25, 1920, when the War Department authorized the establishment of service schools. Flying training took place in Texas, and a technical school for mechanics was at located at Chanute Field, Illinois. The Air Service Tactical School was set up at Langley Field, Virginia, to train officers for higher command and to instruct in doctrine and the employment of military aviation, and later became the Air Corps Tactical School, transferred in 1931 to Maxwell Field, Alabama. The Engineering Division created an air engineering school at McCook Field and moved it to Wright Field when that base was established in 1924.

Groups of the Air Service

| Original Designation | Station | Date created | Redesignation (date) |

| 1st Surveillance Group | Fort Bliss, Texas | July 1, 1919 | 3rd Attack Group² (1921) |

| 2nd Observation Group | Luke Field, Hawaii | August 15, 1919 | 5th Group (Observation)² (1922) |

| 1st Pursuit Group² | Kelly Field, Texas | August 22, 1919 | 1st Group (Pursuit)² (1922) |

| 1st Day Bombardment Group | Kelly Field, Texas | September 18, 1919 | 2d Group (Bombardment)² (1922) |

| 3d Observation Group | France Field, Panama | September 30, 1919 | 6th Group (Observation)² (1922) |

| First Army Observation Group | Langley Field, Virginia | October 1, 1919 | 7th Group (Observation) (1921) |

| 1st Observation Group | Ft. Stotsenburg, Luzon | March 3, 1920 | 4th Group (Composite)² (1922) |

| 9th Observation Group² | Mitchel Field, New York | August 1, 1922 |

- ¹Redesignated, then inactivated until 1928

- ²Original 7 groups of US Army Air Corps

Annual Air Service strength

as of June 30 yearly

| Year | Strength | Year | Strength | Year | Strength | ||

| 1918 | 138,997 | 1921 | 11,830 | 1924 | 10,488 | ||

| 1919 | 24,115 | 1922 | 9,888 | 1925 | 9,719 | ||

| 1920 | 9,358 | 1923 | 9,407 | 1926 | 9,578 |

Heads of the Air Service

Directors of Air Service

- John D. Ryan (August 28, 1918–November 27, 1918)

- Maj.Gen. Charles T. Menoher (January 2, 1919–June 4, 1920)

Chiefs of Air Service

- Maj.Gen. Charles T. Menoher (June 4, 1920–October 4, 1921)

- Maj.Gen. Mason M. Patrick (October 5, 1921–July 2, 1926)

Debate over an independent Air Force

The seven-year history of the Air Service was essentially a prolonged debate between adherents of airpower and the supporters of the traditional military services about the value of an independent Air Force, spurred by the creation of the Royal Air Force in 1918. On one side were Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell, Brig. Gen. Benjamin Foulois, a cadre of young former Reserve officers who made up the overwhelming majority of Army pilots, and a few like-minded politicians and newspapers. Opposed were the General Staff of the U.S. Army, its senior leadership from World War I, and the United States Navy.[37]

While this debate focused largely on the controversial Mitchell, its early star was Foulois. Both returned from France with combat leadership experience in aviation, expecting to become the peacetime leaders of the Air Service. Instead, the War Department had appointed Maj.Gen. Charles Menoher, who had commanded the Rainbow Division in France, to be Director of the Air Service to replace Secretary Ryan, signalling to the nation and the airpower proponents its intent to keep the air arm under the direction of the ground forces.[38]

In 1919, Mitchell proposed a Cabinet-level Department of Aviation equal to the War and Navy Departments to control all aviation, including sea-based air, airmail, and commercial operations. His goal was not only independent and centralized control of airpower, but also encouragement of the peacetime U.S. aviation industry. However, Mitchell insisted that the debate be both broad and civil. Foulois, however, complained bitterly to the United States Congress about the historical neglect and indifference of the Army to its air service. Although a bill actually was introduced in the U.S. Senate to create Mitchell's proposed department and initially garnered strong support, the opposition of the Army's wartime leaders (especially General Pershing) frustrated the effort at the start and resulted in the passage of the less radical though still significant National Defense Act of 1920.[38]

Mitchell was not discouraged by the failure of his first proposal. He recognized the value of public opinion in the debate and changed tactics, embarking on a publicity campaign on behalf of military aviation. General Menoher, when he was unable to persuade the Secretary of War, John Weeks to silence Mitchell, resigned his position on October 4, 1921, and was replaced by Maj.Gen. Mason Patrick. Although an engineer and not an aviator, Patrick had been Pershing's Chief of Air Service in France, where his primary duty had been to coordinate the activities of Foulois and Mitchell, then rivals. Patrick had also testified before Congress against Mitchell's plan for an independent air force.[39]

Patrick was not hostile to aviation, however. He underwent flight training and obtained his wings, then issued a series of reports to the War Department emphasizing the need to expand and modernize the Air Service. Patrick was also critical of the policy that placed air units under the command of corps commanders and proposed that only observation squadrons should be part of the ground forces, with all combat forces centralized under the command of a "General Headquarters Air Force."[40]

The response to the proposal was three boards and committees. The Secretary of War convened the Lassiter Board in 1923, composed of general staff officers who fully endorsed Patrick's views, and adopted the proposal as policy. However, he proposed that appropriations for the GHQ Air Force be merged with those for Naval aviation, which the Navy rejected, and the reorganization could not be implemented.[41]

The U.S. House of Representatives then appointed the Lampert Committee in 1924 to investigate Patrick's criticisms. Mitchell testified before the committee and, upset by the failure of the War Department to even negotiate with the Navy in order to save the reforms of the Lassiter Board, harshly criticized Army leadership and attacked other witnesses. He had already antagonized the senior flag officers of both services with speeches and articles delivered in 1923 and 1924, and the Army refused to retain him as Assistant Chief of the Air Service when his term expired in March, 1925. He was reduced in rank to colonel by Secretary Weeks and exiled to the VIII Corps in San Antonio as air officer, where his continuing criticisms caused President Calvin Coolidge to order his court-martial. Mitchell was convicted in December 1925 and, shortly after, the Lampert Committee issued a compromise recommendation that both military air arms be expanded.[41]

The third board was the Morrow Board, convened by President Coolidge to make a general inquiry into U.S. aviation. Headed by an investment banker and personal friend of Coolidge's, Dwight Morrow, the board was made up of a federal judge, the head of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, former military officers now in industry, and the wartime head of the Board of Aircraft Production. The actual purpose of the Morrow Board was to minimize the political impact of the Mitchell trial, and Coolidge directed that it issue its findings by the end of November, to pre-empt the findings of not only the military court but also of the Lampert Committee that might be contrary to the Morrow Board. The major result of the Morrow Board was to maintain the status quo, but it also made the recommendation, adopted in 1926, that the Air Service be abolished and replaced by an Air Corps equal within the Army to the Signal Corps, but without the autonomy of the Marine Corps within the Navy Department, and thus still relegated as a support arm to the infantry.[42]

Advances in aviation

To positively influence U.S. public opinion and thereby enlist political support in Congress in his crusade for an independent air force, General Mitchell conducted a publicity campaign on behalf of airpower. While using public pronouncements for propaganda purposes, Mitchell also fostered within the Air Service advances in aeronautical science that would not only increase its effectiveness as a military service, but would also generate public support.

His first project, undertaken at McCook Field, in Dayton, Ohio, was for the creation of a heavily armored attack plane for supporting ground forces. Although the designs that resulted were not practical and did not meet Mitchell's specifications for aircraft that could land troops behind enemy lines, the project led Mitchell to closely supervise aircraft development, not only at McCook but in Europe as well. On October 30, 1919, the McCook Field engineers tested the first reversible-pitch propeller.

This effort resulted in the development of a monoplane with retractable landing gear, a metal propeller, and a streamlined engine design, the Verville R-3 Racer. Economy measures by the Air Service prevented the project from being fully completed, but contributed to a growing determination within the Air Service to set new aviation records for speed, altitude, distance, and endurance, which in turn contributed not only to technical improvements (and favorable publicity) but also advancements in aviation medicine.

Air Service pilots established world records in altitude, distance, and speed. Speed in particular attracted public attention and, although a number of speed records were set in cross-country flying, records were also set on measured courses. Mitchell himself set a world speed record of 222.97 mph (358.84 km/h) over a closed course in a Curtiss R-6 racer on October 18, 1922, at the Pulitzer Trophy competition of the 1922 National Air Races. A later world speed record of 232 mph (373 km/h) was made by 1st Lt. James H. Doolittle in winning the Schneider Trophy race at the 1925 Races.

The practical and military applications of speed were not ignored, however. On September 4, 1922, Doolittle had made the first transcontinental crossing in one day, flying from Pablo Beach, Florida, to Rockwell Field, California, in 21 hours, 20 minutes, a distance of 2,163 mi (3,481 km) in a DH-4 of the 90th Squadron.[43] Mitchell concluded that accomplishing the same feat by "daylight only", making only a single stop at Kelly Field, had tremendous value, and staged a dawn-to-dusk transcontinental flight across the United States in the summer of 1924 in a Curtiss PW-8 fighter acquired for the purpose.

Despite the emphasis in the press on speed, the Air Service also established a number of altitude, distance, and endurance records. The Packard-Le Peré LUSAC-11 biplane set world altitude records over McCook Field of 33,114 ft (10,093 m) on February 27, 1920, by Maj. R. W. Schroeder; and 34,507 ft (10,518 m) on September 28, 1921, by Lt. John A. Macready. The first nonstop flight across the U.S., made in 26 hours and 50 minutes at an average speed of 98.76 mph, was made May 2-May 3, 1923, from Roosevelt Field, New York to Rockwell Field in a Fokker T-2 (a converted F.IV airliner) by Macready and Lt. Oakley G. Kelly. The feat was followed in August by a flight in which a DeHavilland DH-4 stayed aloft for more than 37 hours by means of aerial refueling. The Fokker T.2 is on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

The greatest achievement of these projects, however, was the first flight around the world. The Air Service set up support facilities along the proposed route and in April 1924 sent a flight of four aircraft west from Seattle, Washington. Six months later, two aircraft completed the flight. Even if considered as primarily a publicity stunt, the flight was a brilliant accomplishment in which five nations had already failed.

Kelly and Macready, Doolittle, and the crews of the circumnavigation flight all won the Mackay Trophy for the respective years in which they accomplished their feats.

Notable members of the Air Service

- Henry H. Arnold, aviation pioneer; Commanding General of the United States Army Air Forces

- Hobey Baker, star athlete at Princeton University

- Hiram Bingham III, United States Senator from Connecticut

- Clayton Bissell, World War I ace, commander of Tenth Air Force during World War II

- Erwin R. Bleckley, artillery officer assigned to the Air Service and Medal of Honor recipient

- Raynal Bolling, executive of US Steel; first high-ranking casualty of World War I

- Leighton Brewer, poet and professor of English at Boston University

- Arthur Raymond Brooks, World War I ace

- Douglas Campbell, first American ace

- Merian C. Cooper, adventurer and Hollywood film producer

- Jimmy Doolittle, daredevil pilot, aeronautical engineer, World War II general

- Ira Eaker, commander of U.S. Eighth Air Force during World War II

- Benjamin Delahauf Foulois, aviation pioneer

- Harold Ernest Goettler, Medal of Honor recipient

- Edgar S. Gorrell, Air Service historian and later president of Stutz Motor Company

- James Norman Hall, author

- Charles W. "Chic" Harley, All-American college football player

- Arthur Harvey, oil pioneer, author

- Howard Hawks, film director

- Field Kindley, World War I ace

- Fiorello LaGuardia, U.S. Representative and Mayor of New York

- Charles Lindbergh, aviation pioneer; first solo pilot to fly the Atlantic non-stop

- Raoul Lufbery, member of Lafayette Escadrille and air tactics pioneer

- Frank Luke, ace and Medal of Honor recipient

- Thomas DeWitt Milling, aviation pioneer and first certified U.S. military pilot

- John Purroy Mitchel, advocate of universal military training and youngest mayor of New York City

- Billy Mitchell, airpower visionary

- Odas Moon, pioneer in aerial refueling and bombing doctrine

- Charles Nordhoff, co-author of Mutiny on the Bounty

- Eddie Rickenbacker, highest ranking U.S. ace of World War I and Medal of Honor recipient

- Quentin Roosevelt, youngest son of President Theodore Roosevelt

- John Monk Saunders, author and screenwriter of Academy Award-winning films Wings and The Dawn Patrol

- Carl Andrew Spaatz, first Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force

- Stephen W. Thompson, First Aerial Victory by the U. S. military

- George Augustus Vaughn, Jr. World War I Ace

- Alfred V. Verville, aircraft designer (Verville-Sperry R-3 Racer and M-1 Messenger currently displayed in the National Air and Space Museum)

- William Wellman, Hollywood film director

- Charles A. Willoughby, World War II general in the United States Army

- John Gilbert Winant, educator, governor of New Hampshire, and ambassador to Britain during World War II

See also

- List of American Aero Squadrons

- List of American Balloon Squadrons

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Army Air Forces in World War II: Plans and Early Operations: Section I, The Air Service in World War I". Hyper-War. http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/AAF/I/AAF-I-1.html. Retrieved 17 January 2009.

- ↑ Sweetser, Arthur (1919). The American Air Service: A Record of its Problems, Its Difficulties, Its Failures, and Its Final Achievements, Appleton and Company, pp. 215-219; and Bassett, John Spencer (1919). Our War With Germany, Alfred A. knopf, pp. 181-184.

- ↑ Futrell, Robert Frank (1971, 1991). Ideas, Concepts, and Doctrines: Basic Thinking in the United States Air Force 1907-1960, Air University Press, p. 21.

- ↑ Report of the Secretary of War, 1919. United States War Department.. http://books.google.com/books?id=bZcsAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA51&lpg=PA51&dq=John+D.+Ryan+1918+%22Second+Assistant+Secretary+of+War%22&source=web&ots=rtRgxY9h6P&sig=U-PDktOz_zL6I-_XZGWFMyV0YBI&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=8&ct=result#PPA55,M1. Retrieved 17 January 2009., p. 51.

- ↑ Futrell (1971), p. 28.

- ↑ Manufacturers' Aircraft Association, Inc. (1920) Aircraft Year Book, Doubleday, page and Co., pp. 80-81.

- ↑ Report of the Secretary of War, 1919. United States War Department.. http://books.google.com/books?id=bZcsAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA51&lpg=PA51&dq=John+D.+Ryan+1918+%22Second+Assistant+Secretary+of+War%22&source=web&ots=rtRgxY9h6P&sig=U-PDktOz_zL6I-_XZGWFMyV0YBI&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=8&ct=result#PPA55,M1. Retrieved 17 January 2009., p. 56.

- ↑ Maurer, Maurer, ed. (1978). The U.S. Air Service in World War I; Volume I: The Final Report and a Tactical History, Diane Publishing, ISBN 1428916040, p. 51. (This source is Volume I of four volumes on Air Service activities in World War I, reproduced from summary reports of the 30-volume "Gorrell's History" of the AS of the AEF, compiled and written by Colonel Edgar S. Gorrell and a staff of several hundred at Tours in 1919, and updated by research from the USAF Center for Air Force History, Maxwell AFB.)

- ↑ Mortenson, Daniel R. (1997). "The Air Service in the Great War," Winged Shield, Winged Sword: A History of the United States Air Force, ISBN 0-16-049009-X, p. 43.

- ↑ Maurer, Maurer (1978). The U.S. Air Service in World War I; Volume II: Early Concepts of Military Aviation, p. 107.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. II, p. 113.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. II, p. 125.

- ↑ Mortenson (1997), p. 60.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.71.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Report of the Secretary of War, 1919. United States War Department.. http://books.google.com/books?id=bZcsAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA51&lpg=PA51&dq=John+D.+Ryan+1918+%22Second+Assistant+Secretary+of+War%22&source=web&ots=rtRgxY9h6P&sig=U-PDktOz_zL6I-_XZGWFMyV0YBI&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=8&ct=result#PPA55,M1. Retrieved 17 January 2009., p. 55.

- ↑ Each pursuit squadron was authorized 25 aircraft, including seven reserve spares, and 18 pilots.

- ↑ Observation squadrons had 24 airplanes including 6 spares, 18 pilots, and 18 observers.

- ↑ Day bombardment squadrons had 25 aircraft including spares, and 18 pilots. Night bombardment squadrons had 14 aircraft including spares, 10 pilots, and 10 observers.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.391.

- ↑ 1st, 2nd, 4th, 32nd, 42nd, 89th, and 90th Divisions. Three other divisions (5th, 33rd, and 37th) guarded the line of communications through Belgium and Luxembourg.

- ↑ Cooke, James J. (1996). The U.S. Air Service in the Great War, 1917-1919. Preager Press. ISBN 0275948625. P. 204.

- ↑ Cooke (1996), p. 208.

- ↑ Cooke (1996), p. 216.

- ↑ Cooke (1996), p. 198. Quoting Mitchell, there were 196 American-made, 16 British-made, and 528 French-made aircraft.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.17.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.85.

- ↑ Maurer, Vol. I, p.120.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.26.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.78.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.105.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.112.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.106.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.110.

- ↑ AIR FORCE Magazine 2006 Almanac The actual number is confused. Gorrell originally reported 118 aces, but the Air Service followed the French practice of crediting each aviator participating in a kill with a whole victory, forcing a review by USAF from 1965-1969 that revised total kills. A preliminary assessment by the USAF (Historical Study 73) recognized 69 Air Service aces. Its final product, USAF Historical Study 133, credited 71 aces. The review identified 491 kills made by one pilot against one aircraft. An additional 342 kills resulted in 1022 partial credits. None of the figures includes kills made by members while they previously served in a foreign air service.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.27.

- ↑ Maurer (1978), Vol. I, p.46-47.

- ↑ Shiner, Lt. Col. John F. (1997). "From Air Service to Air Corps: The Era of Billy Mitchell," Winged Shield, Winged Sword: A History of the United States Air Force Vol. I, ISBN 0-16-049009-X, p. 72, 74.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Shiner (1997), p. 73.

- ↑ Shiner (1997), p. 82.

- ↑ Shiner (1997), p. 96.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Shiner (1997), p.97.

- ↑ Shiner (1997), p. 102-103.

- ↑ "Remembering Our Heritage". Alaska Wing, Commemorative Air Force. http://www.alaskawingcaf.org/Alaska%20Heritage/September3-9.pdf. Retrieved 28 January 2010.

- Bowman, Martin W., "Background to War", USAAF Handbook 1939-1945, ISBN 0-8117-1822-0

- Mortenson, Daniel R., "The Air Service in the Great War," Winged Shield, Winged Sword: A History of the United States Air Force, Vol. I, Chapter 2 (1997), ISBN 0-16-049009-X

- Shiner, Lt. Col. John F., "From Air Service to Air Corps: The Era of Billy Mitchell," Winged Shield, Winged Sword: A History of the United States Air Force Vol. I, Chapter 3 (1997), ISBN 0-16-049009-X

- Maurer Maurer (ed.) (1978). The U.S. Air Service in World War I, Volume I: The Final Report and A Tactical History

- Maurer Maurer Combat squadrons of the Air Force, World War II, USAF Historical Study 82 large PDF file

- "Chapter 1: The Air Service in World War I" Craven, Wesley and James Cate, eds. The Army Air Forces In World War II, Volume I: Plans and Early Operations January 1939 to August 1942.

- "2006 Almanac," Air Force Magazine, May 2006, Vol. 89, No. 5, the Air Force Association, Arlington, Virginia

- Army Air Forces Statistical Digest, Table 3

- The American Army in the World War, A Divisional Record Of The American Expeditionary Forces in Europe, G Waldo Browne, Rosencrans W. Pillsbury, 1921, Overseas Book Co, Manchester, New Hampshire.

External links

- Military Times Hall of Fame, listing of 567 citations for gallantry for Air Service members

- 1st Pursuit Group history at www.acepilots.com

- United States Air Service overview, history and 90th Anniversary celebration photos at www.usaww1.com

- United States Air Service interactive Google Map of bases, etc. at www.usaww1.com

- 1st Pursuit Group history at www.1stfighter.com

- 50th Aero Squadron Harold Goettler and Erwin Bleckley to be Honored October 7, 2009

- History of the US 22nd Aero Squadron by Arthur R. Brooks (.pdf)

- Army Air Service Recruiting Film - Balloon and Airship Division at YouTube - Call of the Air silent

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

| Preceded by Division of Military Aeronautics |

United States Army Air Service 1918-1926 |

Succeeded by United States Army Air Corps |