Manuscript

A manuscript or handwrit is a recording of information that has been manually created by someone or some people, such as a hand-written letter, as opposed to being printed or reproduced some other way. The term may also be used for information that is hand-recorded in other ways than writing, for example inscriptions that are chiselled upon a hard material or scratched (the original meaning of graffiti) as with a knife point in plaster or with a stylus on a waxed tablet, (the way Romans made notes), or are in cuneiform writing, impressed with a pointed stylus in a flat tablet of unbaked clay. The word manuscript derives from the Medieval Latin manuscriptum, a word first recorded in 1594 as a latinisation of earlier Germanic words used in the Middle Ages: compare Middle High German hantschrift (c. 1450), Old Norse handrit (bef. 1300), Old English handgewrit (bef. 1150), all meaning "manuscript", literally, "written by hand".

In publishing and academic contexts, a "manuscript" is the text submitted to the publisher or printer in preparation for publication, usually as a typescript prepared on a typewriter, or today, a printout from a PC, prepared in manuscript format.

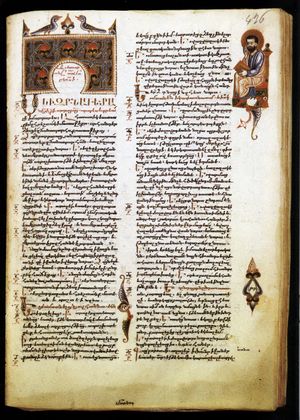

Manuscripts are not defined by their contents, which may combine writing with mathematical calculations, maps, explanatory figures or illustrations. Manuscripts may be in the form of scrolls or in book form, or codex format. Illuminated manuscripts are enriched with pictures, border decorations, elaborately engrossed initial letters or full-page illustrations.

Contents |

Cultural Background

The traditional abbreviations are MS for manuscript and MSS for manuscripts.[1][2] The second s is not simply the plural; by an old convention, it doubles the last letter of the abbreviation to express the plural, just as pp. means "pages".

Before the invention of woodblock printing in China or by moveable type in a printing press in Europe, all written documents had to be both produced and reproduced by hand. Historically, manuscripts were produced in form of scrolls (volumen in Latin) or books (codex, plural codices). Manuscripts were produced on vellum and other parchments, on papyrus, and on paper. In Russia birch bark documents as old as from the 11th century have survived. In India the Palm leaf manuscript, with a distinctive long rectangular shape, was used from ancient times until the 19th century. Paper spread from China via the Islamic world to Europe by the 14th century, and by the late 15th century had largely replaced parchment for many purposes.

When Greek or Latin works were published, numerous professional copies were made simultaneously by scribes in a scriptorium, each making a single copy from an original that was declaimed aloud.

The oldest written manuscripts have been preserved by the perfect dryness of their Middle Eastern resting places, whether placed within sarcophagi in Egyptian tombs, or reused as mummy-wrappings, discarded in the middens of Oxyrhynchus or secreted for safe-keeping in jars and buried (Nag Hammadi library) or stored in dry caves (Dead Sea scrolls). Manuscripts in Tocharian languages, written on palm leaves, survived in desert burials in the Tarim Basin of Central Asia. Volcanic ash preserved some of the Greek library of the Villa of the Papyri in Herculaneum.

Ironically, the manuscripts that were being most carefully preserved in the libraries of Antiquity are virtually all lost. Papyrus has a life of at most a century or two in relatively moist Italian or Greek conditions; only those works copied onto parchment, usually after the general conversion to Christianity, have survived, and by no means all of those.

Originally, all books were in manuscript form. In China, and later other parts of East Asia, Woodblock printing was used for books from about the seventh century. The earliest dated example is the Diamond Sutra of 868. In the Islamic world and the West, all books were in manuscript until the introduction of movable type printing in about 1450. Manuscript copying of books continued for a least a century, as printing remained expensive. Private or government documents remained hand-written until the invention of the typewriter in the late nineteenth century. Because of the likelihood of errors being introduced each time a manuscript was copied, the filiation of different version of the same text is a fundamental part of the study and criticism of all texts that have been transmitted in manuscript.

In Southeast Asia, in the first millennium, documents of sufficiently great importance were inscribed on soft metallic sheets such as copperplate, softened by refiner's fire and inscribed with a metal stylus. In the Philippines, for example, as early as 900, specimen documents were not inscribed by stylus, but were punched much like the style of today's dot-matrix printers. This type of document was rare compared to the usual leaves and bamboo staves that were inscribed. However, neither the leaves nor paper were as durable as the metal document in the hot, humid climate. In Burma, the kammavaca, buddhist manuscripts, were inscribed on brass, copper or ivory sheets, and even on discarded monk robes folded and lacquered. In Italy some important Etruscan texts were similarly inscribed on thin gold plates: similar sheets have been discovered in Bulgaria. Technically, these are all inscriptions rather than manuscripts.

The study of the writing, or "hand" in surviving manuscripts is termed palaeography. In the Western world, from the classical period through the early centuries of the Christian era, manuscripts were written without spaces between the words (scriptio continua), which makes them especially hard for the untrained to read. Extant copies of these early manuscripts written in Greek or Latin and usually dating from the 4th century to the 8th century, are classified according to their use of either all upper case or all lower case letters. Hebrew manuscripts, such as the Dead Sea scrolls make no such differentiation. Manuscripts using all upper case letters are called majuscule, those using all lower case are called minuscule. Usually, the majuscule scripts such as uncial are written with much more care. The scribe lifted his pen between each stroke, producing an unmistakable effect of regularity and formality. On the other hand, while minuscule scripts can be written with pen-lift, they may also be cursive, that is, use little or no pen-lift.

Modern variations

In the context of library science, a manuscript is defined as any hand-written item in the collections of a library or an archive; for example, a library's collection of the letters or a diary that some historical personage wrote. Such manuscript collections are described in finding aids, similar to an index or table of contents to the collection, in accordance with national and international content standards such as DACS and ISAD(G).

In other contexts, however, the use of the term "manuscript" no longer necessarily means something that is hand-written. By analogy a typescript has been produced on a typewriter.

In book, magazine, and music publishing, a manuscript is an original copy of a work written by an author or composer, which generally follows standardized typographic and formatting rules. (The staff paper commonly used for handwritten music is, for this reason, often called "manuscript paper.") In film and theatre, a manuscript, or script for short, is an author's or dramatist's text, used by a theater company or film crew during the production of the work's performance or filming. More specifically, a motion picture manuscript is called a screenplay; a television manuscript, a teleplay; a manuscript for the theater, a stage play; and a manuscript for audio-only performance is often called a radio play, even when the recorded performance is disseminated via non-radio means.

In insurance, a manuscript policy is one that is negotiated between the insurer and the policyholder, as opposed to an off-the-shelf form supplied by the insurer.

European Manuscript History

Almost all surviving manuscripts use the codex format (as in a modern book), which had replaced the scroll by Late Antiquity. Parchment, or vellum as the best type of parchment is known had also replaced papyrus, which was not nearly so long lived and has survived to the present only in the extremely dry conditions of Egypt, although it was widely used across the Roman world. Parchment is made of animal skin, normally calf, sheep, and/or goat, but also other animals. With all skins, the quality of the finished product is based on how much preparation and skill was put into turning the skin into parchment. Parchment made from calf or sheep was the most common in Northern Europe, while in Southern Europe, those civilizations preferred goatskin [3]. Often, if the parchment is white or cream in color and veins from the animal can still be seen, it is calfskin. If it is yellow, greasy or in some cases shiny, then it was made from sheepskin[3].

Vellum comes from the Latin word vitulinum which means “of calf”/ “made from calf”. For modern parchment makers and calligraphers, and apparently often in the past, the terms parchment and vellum are used based on the different degrees of quality, preparation and thickness, and not according to which animal the skin came from, and because of this, the more neutral term "membrane" is often used by modern academics, especially where the animal has not been established by testing.[3].

Prepare a Manuscript

The first stage in creating a manuscript is to prepare the skin so that the writer can write on it. The skin is washed with water and lime, but not together, and it has to soak in the lime for a couple of days.[1] The hair was removed. The skin was dried by tension. The skin is put into a frame (image). The frame is called a herse.[3] The parchment maker attached the skin at points around the circumference. The skin is attached to herse by cords, to prevent tearing the maker wrapped the area of the skin to which the cord is to be attached around a pebble, this pebble is called a pippin[3]. After that is complete, the maker will use a crescent shaped knife, called lunarium or lunellum, to clean an surviving hairs. Once the skin is completely dry, will be given a deep clean, and it will be processed into sheets. The number of sheets out of piece of skin depends on the size of the skin and the given dimensions requested by the order. For example, the average calfskin can provide three and half medium sheets of writing material. This can be doubled when it is folded into two conjoint leaves, also known as a bifolium. Historians have found evidence of manuscripts where the scribe wrote down the medieval instructions now followed by modern membrane makers[4] . Of course with any natural made product there will be some defects.Defects can be any sort of mistake in the membrane. Wither it was human error during the preparation period or from when the animal was killed. Defects can also appear durning the writing process. And unless it is kept in perfect condition, defects can appear later in the manuscript’s life as well.

Preparation of the pages for Writing

Before anything a scribe can do, the membrane must be prepared . This will be listed in steps, as they occur today when making traditional animal skin manuscripts and as they did back in the Middle Ages. The first step is to setup the quires. The quires is a group of several sheets put together. Raymond Clemens and Timothy Graham point out, in "Introduction to Manuscript Studies", that “the quire was the scribe’s basic writing unit throughout the Middle Ages”[3]

Pricking and Ruling the Leaves

In "Introduction to Manuscript Studies", Clemens and Graham define pricking and ruling perfectly

“Pricking is the process of making holes in a sheet of parchement (or membrane) in preparation of it ruling. The lines were then made by ruling between the prick marks”[3]

and on ruling “ The process of entering ruled lines on the page to serve as a guide for entering text. Most manuscripts were ruled with horizontal lines that served as the baselines on which the text was entered and with vertical bounding lines that marked the boundaries of the columns”[3]

After this stage, the scribe would get to work copying from the original work to his collection of sheets of parchment.

Forming the Quire

The scribe, usually a monk,would decide on what his quire would look like, by arranging the hair and flesh sides of the sheets. Throughout time from Carolingian period and all the way up to the Middles Ages, different styles of folding the quire came about. For example, though out mainland Europe throughout the Middle Ages, the quire would be put into a system which each side would fold on to the same style. The hair side would meet the hair side and the same goes with the flesh side. This was not the same style used in the British Isles, where the membrane would be folded so that it turned out a eight leaf quire, with single leaves in the third and sixth positions[3]. Once the scribe has it the way that he wants, the next stage was tacking the quire. Tacking is when the scribe would hold together the leaves in quire with thread. Once threaded together, the scribe would then sew a line of parchment up the “spine” of the manuscript, as to protect the tacking.

A Sample of Common Genres of Manuscripts

From Ancient texts to Medieval Maps, anything written down for study would have been done with manuscripts. Some of the most common genres were Bibles, Religious Commentaries, Philosophy, Law and government texts.

Bibles

“The Bible was the most studied book of the Middle Ages.”[5] The Bible was the center of medieval religious life. Along with the Bible, came scores of commentaries. Commentaries were written in volumes, with some focusing on just single pages of scripture. Across Europe, there were universities that prided themselves on their biblical knowledge. Along with Universities, certain cities also had their own celebrities of the medieval

Book of Hours

book of hours The book of hours was a devotional book popular in the Middle Ages. It is the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Like every manuscript, each manuscript book of hours is unique in one way or another, but most contain a similar collection of texts, prayers and psalms, often with appropriate decorations, for Christian devotion. Illumination or decoration is minimal in many examples, often restricted to decorated capital letters at the start of psalms and other prayers, but books made for wealthy patrons may be extremely lavish, with full-page miniatures.

Liturgical Books and Calendars

Along with Bibles, large numbers of manuscripts made in the Middle Ages were used in Church. Due to the church’s complex system of rituals and worship, these books were finally written and most decorated of all medieval manuscripts. Liturgical books, usually, came in two varieties. Those used during Mass and those for Divine Office. [3]

Most liturgical books came with a calendar in the front.This served served a quick reference point for important dates in Christ’s life and to tell Church officials which Saints were to be honored and on what day. The format of the Liturgical Calendar was as followed:

an example of a medieval liturgical calendar

| January,August, December | March,May,July,October | April, June, September, November | February |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kal. (1) | Kal. (1) | Kal. (1) | Kal. (1) |

| IV Non. (2) | VI Non. (2) | IV Non. (2) | IV Non. (2) |

| III Non. (3) | V Non. (3) | III Non. (3) | III Non. (3) |

| II Non. (4) | IV Non. (4) | II Non. (4) | II Non. (4) |

| Non. (5) | III Non. (5) | Non. (5) | Non. (5) |

| VIII Id. (6) | II Non. (6) | VIII Id. (6) | VIII Id. (6) |

| VII Id. (7) | Non. (7) | VII Id. (7) | VII Id. (7) |

| VI Id. (8) | VIII Id. (8) | VI Id. (8) | VI Id. (8) |

| V Id. (9) | VII Id. (9) | V Id. (9) | V Id. (9) |

| IV Id. (10) | VII Id. (10) | IV Id. (10) | IV Id. (10) |

| III Id. (11) | V Id. (11) | III Id. (11) | III Id. (11) |

| II Id. (12) | IV Id. (12) | II Id. (12) | II Id. (12) |

| Id (13) | III Id. (13) | Id. (13) | Id. (13) |

| XIX Kal. (14) | II Id. (14) | XVIII Kal. (14) | XVI Kal. (14) |

| XVIII Kal. (15) | Id. (15) | XVII Kal. (15) | XV Kal. (15) |

| XVII Kal. (16) | XVII Kal. (16) | XVI Kal. (16) | XIV Kal. (16) |

| XVI Kal. (17) | XVI Kal. (17) | XV Kal. (17) | XIII Kal. (17) |

| XV Kal. (18) | XV Kal. (18) | XIV Kal. (18) | XII Kal. (18) |

| XIV Kal. (19) | XIV Kal. (19) | XIII Kal. (19) | XI Kal. (19) |

| XIII Kal. (20) | XIII Kal. (20 | XII Kal. (20) | X Kal. (20) |

| XII Kal. (21) | XII Kal. (21) | XI Kal. (21) | IX Kal. (21) |

| XI Kal. (22) | XI Kal. (22) | X Kal. (22) | VIII Kal. (22) |

| X Kal. (23) | X Kal. (23) | IX Kal. (23) | VII Kal. (23) |

| IX Kal. (24) | IX Kal. (24) | VIII Kal. (24) | VI Kal (the extra day in a leap year) |

| VIII Kal. (25) | VIII Kal. (25) | VII Kal. (25) | VI Kal. (24/25) |

| VII Kal. (26) | VII Kal. (26) | VI Kal. (26) | V Kal. (25/26) |

| VI Kal. (27) | VI Kal. (27) | V Kal. (27) | V Kal. (26/27) |

| V Kal. (28) | V Kal. (28) | V Kal. (28) | V Kal. (28) |

| IV Kal. (29) | IV Kal. (29) | III Kal. (29) | III Kal. (28/29) |

| III Kal. (30) | III Kal. (30) | II Kal. (30) | |

| II Kal. (31) | II Kal. (31) |

Almost all medieval calendars give each day’s date according to the Roman method of reckoning time. In the Roman system, each month had three fixed points, known as Kalends (Kal), the Nons and the Ides. The nones fell on the fifth of the month in January, February, April, June, August, September, November and December, but on the seventh of the month in March,May, July and October. The ides ell on the thirteenth in those months in which the nones fell on the fifth, and the fifteenth in the other four months. All other days were dated by the number of days by which they preceded one of those fixed points.[3] [6]

Different Scripts

Merovingian script, or "Luxeuil minuscule", is named after an abbey in Western France, the Luxeuil Abbey, founded by the Irish missionary St Columba in ca.590. [7] [8] Caroline minuscule is a script developed as a writing standard in Europe so that the Roman alphabet could be easily recognized by the small literate class from one region to another. It was used in Charlemagne's empire between approximately 800 and 1200. Codices, classical and Christian texts, and educational material were written in Carolingian minuscule throughout the Carolingian Renaissance. The script developed into blackletter and became obsolete, though its revival in the Italian renaissance forms the basis of more recent scripts.[3] In Introduction to Manuscript Studies, Clemens and Graham associate the beginning of this text coming from the Abby of Saint-Martin at Tours. [3]

Caroline Minuscule arrived in England in the second half of the 10th century. Its adoption there, replacing Insular script, was encouraged by the importation of continental European manuscripts by Saints Dunstan, Aethelwold, and Oswald. This script spread quite rapidly, being employed in many English centres for copying Latin texts. English scribes adapted the Carolingian script, giving it proportion and legibility.[9] This new revision of the Caroline Minuscule was called English Protogothic Bookhand. Another script that is derived from the Caroline Minuscule was the German Protogothic Bookhand. It originated in southern Germany during the second half of the 12 century. [9] All the indiviual letters are Caroline; but just as with English Protogothic Bookhand it evolved. This can be seen most notably in the arm of the letter h. It has a hairline tapers out by curving to the left. When first read the German Protogothic h looks like the German Protogothic b. [10] Many more scripts sprung out of the German Protogothic Bookhand. After those came Bastard Anglicana, which is best described as: The coexistence in the Gothic period of formal hands employed for the copying of books and cursive scripts used for documentary purposes eventually resulted in cross-fertilization between these two fundamentally different writing styles. Notably, scribes began to upgrade some of the cursive scripts that has been thus formalized is known as abastard script (whereas a bookhand that has had cursive elementas fused onto it is known as a hybrid script). The advantage of such a script was that it could be written more quickly than a pure bookhand; it thus recommended itself to scribes in a period when demand for books was increasing and authors were tending to write longer texts. In England during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, many books were written in the script known as Bastard Anglicana.

The coexistence in the Gothic period of formal hands employed for the copying of books and cursive scripts used for documentary purposes eventually resulted in cross-fertilization between these two fundamentally different writing styles. Notably, scribes began to upgrade some of the cursive scripts that has been thus formalized is known as a bastard script (whereas a bookhand that has had cursive elementas fused onto it is known as a hybrid script). The advantage of such a script was that it could be written more quickly than a pure bookhand; it thus recommended itself to scribes in a period when demand for books was increasing and authors were tending to write longer texts. In England during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, many books were written in the script known as Bastard Anglicana.

Major US Repositories of Medieval Manuscripts

- Matenadaran (Yerevan, Armenia)= more than 17,000

- Pierpont Morgan = 1,300 (including papyri)

- Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale = 1,100

- Houghton Library, Harvard = 850

- Princeton University library = 500

- Huntington Library = 400

- Newberry Library = 260

- Cornell University Library = 150

See also

- Armenian Illuminated manuscript

- Genkō yōshi

- Gospel Book

- List of Hiberno-Saxon illustrated manuscripts

- Manuscript culture

- Miniature (illuminated manuscript)

- Music manuscript

- Preservation of Illuminated Manuscripts

- Printing press

- Voynich manuscript

- Woodblock printing

External links

- British Library Glossary of manuscript terms, mostly relating to Western medieval manuscripts

- Centre for the History of the Book, University of Edinburgh

- Chinese Codicology

- Manuscripts Department, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- The Sarasvati Mahal Library, has the richest collection of manuscripts in Sanskrit, Tamil, Marathi and Telugu

- The Schøyen Collection - the world's largest private collection of manuscripts of all types, with many descriptions and images

"Manuscripts". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Manuscripts". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.- Newberry Library Manuscript Search

- Getty Exhibitions

Work Cited

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "Manuscript." Online Etymology Dictionary. Nov. 2001. Accessed 10-11-2007.

- ↑ "Medieval English Literary Manuscripts." www.Library.Rochester.Edu. 22 June 2004. University of Rochester Libraries. Accessed 10-11-2007.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008.

- ↑ Thompson, Daniel. "Medieval Parchment-Making." The Library 16, no. 4 (1935).

- ↑ Beryl Smalley, The Study of the Bible in the Middle Ages. 3rd ed. (Oxford, 1983), xxvii

- ↑ F.P. Pickering, The Calendar Pages of Medieval Service Books: An Introductory Note for Art Historians (Reading, UK., 1980.

- ↑ Brown,Michelle P. Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts. Toronto, 1991.

- ↑ Brown, Michelle P. A Guide to Western Historical Scripts from Antiquity to 1600. Toronto,1990.

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. "English Protogothic Bookhand." In Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008. 146-147.

- ↑ Clemens, Raymond, and Timothy Graham. "German Protogothic Bookhand." In Introduction to Manuscript Studies. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008. 149-150.