Alan Turing

| Alan Turing | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 23 June 1912 Maida Vale, London, England, United Kingdom |

| Died | 7 June 1954 (aged 41) Wilmslow, Cheshire, England, United Kingdom |

| Residence | United Kingdom |

| Nationality | British |

| Fields | Mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst, computer scientist |

| Institutions | University of Manchester National Physical Laboratory Government Code and Cypher School University of Cambridge |

| Alma mater | University of Cambridge Princeton University |

| Doctoral advisor | Alonzo Church |

| Doctoral students | Robin Gandy |

| Known for | Halting problem Turing machine Cryptanalysis of the Enigma Automatic Computing Engine Turing Award Turing Test Turing patterns |

| Notable awards | Officer of the Order of the British Empire Fellow of the Royal Society |

Alan Mathison Turing, OBE, FRS (pronounced /ˈtjʊərɪŋ/ TYOOR-ing; 23 June 1912 – 7 June 1954), was an English mathematician, logician, cryptanalyst and computer scientist. He was influential in the development of computer science and providing a formalisation of the concept of the algorithm and computation with the Turing machine, playing a significant role in the creation of the modern computer.[1]

During the Second World War, Turing worked for the Government Code and Cypher School at Bletchley Park, Britain's codebreaking centre. For a time he was head of Hut 8, the section responsible for German naval cryptanalysis. He devised a number of techniques for breaking German ciphers, including the method of the bombe, an electromechanical machine that could find settings for the Enigma machine. After the war he worked at the National Physical Laboratory, where he created one of the first designs for a stored-program computer, the ACE.

Towards the end of his life Turing became interested in mathematical biology. He wrote a paper on the chemical basis of morphogenesis,[2] and he predicted oscillating chemical reactions such as the Belousov–Zhabotinsky reaction, which were first observed in the 1960s.

Turing's homosexuality resulted in a criminal prosecution in 1952—homosexual acts were illegal in the United Kingdom at that time—and he accepted treatment with female hormones (chemical castration) as an alternative to prison. He died in 1954, several weeks before his 42nd birthday, from cyanide poisoning. An inquest determined it was suicide; his mother and some others believed his death was accidental. On 10 September 2009, following an Internet campaign, then-British Prime Minister Gordon Brown made an official public apology on behalf of the British government for the way in which Turing was treated after the war.[3]

Contents |

Childhood and youth

Alan Turing was conceived in Chhatrapur, Orissa, India.[4] His father, Julius Mathison Turing, was a member of the Indian Civil Service. Julius and wife Sara (née Stoney; 1881–1976, daughter of Edward Waller Stoney, chief engineer of the Madras Railways) wanted Alan to be brought up in England, so they returned to Maida Vale,[5] London, where Alan Turing was born on 23 June 1912, as recorded by a blue plaque on the outside of the building,[6] now the Colonnade Hotel.[7][8] He had an elder brother, John. His father's civil service commission was still active, and during Turing's childhood years his parents travelled between Hastings, England[7] and India, leaving their two sons to stay with a retired Army couple. Very early in life, Turing showed signs of the genius he was to display more prominently later.[9]

His parents enrolled him at St Michael's, a day school, at the age of six. The headmistress recognised his talent early on, as did many of his subsequent educators. In 1926, at the age of 14, he went on to Sherborne School, a famous independent school in the market town of Sherborne in Dorset. His first day of term coincided with the General Strike in Britain, but so determined was he to attend his first day that he rode his bicycle unaccompanied more than 60 miles (97 km) from Southampton to school, stopping overnight at an inn.[10]

Turing's natural inclination toward mathematics and science did not earn him respect with some of the teachers at Sherborne, whose definition of education placed more emphasis on the classics. His headmaster wrote to his parents: "I hope he will not fall between two stools. If he is to stay at Public School, he must aim at becoming educated. If he is to be solely a Scientific Specialist, he is wasting his time at a Public School".[11] Despite this, Turing continued to show remarkable ability in the studies he loved, solving advanced problems in 1927 without having even studied elementary calculus. In 1928, aged 16, Turing encountered Albert Einstein's work; not only did he grasp it, but he extrapolated Einstein's questioning of Newton's laws of motion from a text in which this was never made explicit.[12]

Turing's hopes and ambitions at school were raised by the close friendship he developed with a slightly older fellow student, Christopher Morcom, who was Turing's first love interest. Morcom died suddenly only a few weeks into their last term at Sherborne, from complications of bovine tuberculosis, contracted after drinking infected cow's milk as a boy.[13] Turing's religious faith was shattered and he became an atheist. He adopted the conviction that all phenomena, including the workings of the human brain, must be materialistic,[14] but he still believed in the survival of the spirit after death.[15]

University and work on computability

After Sherborne, Turing went to study at King's College, Cambridge. He was an undergraduate there from 1931 to 1934, graduating with first-class honours in Mathematics, and in 1935 was elected a fellow at King's on the strength of a dissertation on the central limit theorem.[16]

In his momentous paper "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem"[17] (submitted on 28 May 1936), Turing reformulated Kurt Gödel's 1931 results on the limits of proof and computation, replacing Gödel's universal arithmetic-based formal language with what are now called Turing machines, formal and simple devices. He proved that some such machine would be capable of performing any conceivable mathematical computation if it were representable as an algorithm. He went on to prove that there was no solution to the Entscheidungsproblem by first showing that the halting problem for Turing machines is undecidable: it is not possible to decide, in general, algorithmically whether a given Turing machine will ever halt. While his proof was published subsequent to Alonzo Church's equivalent proof in respect to his lambda calculus, Turing was unaware of Church's work at the time.

In his memoirs Turing wrote that he was disappointed about the reception of this 1936 paper and that only two people had reacted – these being Heinrich Scholz and Richard Bevan Braithwaite.

Turing's approach is considerably more accessible and intuitive. It was also novel in its notion of a 'Universal (Turing) Machine', the idea that such a machine could perform the tasks of any other machine. Or in other words, is provably capable of computing anything that is computable. Turing machines are to this day a central object of study in theory of computation, the simplest example being a 2 state 3 symbol Turing machine discovered by Stephen Wolfram.[18]

The paper also introduces the notion of definable numbers.

From September 1936 to July 1938 he spent most of his time at the Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, New Jersey, studying under Alonzo Church. As well as his pure mathematical work, he studied cryptology and also built three of four stages of an electro-mechanical binary multiplier.[19] In June 1938 he obtained his Ph.D. from Princeton; his dissertation introduced the notion of relative computing, where Turing machines are augmented with so-called oracles, allowing a study of problems that cannot be solved by a Turing machine.

Back in Cambridge, he attended lectures by Ludwig Wittgenstein about the foundations of mathematics.[20] The two argued and disagreed, with Turing defending formalism and Wittgenstein arguing that mathematics does not discover any absolute truths but rather invents them.[21] He also started to work part-time with the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS).

Cryptanalysis

During the Second World War, Turing was a main participant in the efforts at Bletchley Park to break German ciphers. Building on cryptanalysis work carried out in Poland by Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Różycki and Henryk Zygalski from Cipher Bureau before the war, he contributed several insights into breaking both the Enigma machine and the Lorenz SZ 40/42 (a Teletype cipher attachment codenamed "Tunny" by the British), and was, for a time, head of Hut 8, the section responsible for reading German naval signals.

Since September 1938, Turing had been working part-time for the Government Code and Cypher School (GCCS), the British code breaking organisation. He worked on the problem of the German Enigma machine, and collaborated with Dilly Knox, a senior GCCS codebreaker.[22] On 4 September 1939, the day after the UK declared war on Germany, Turing reported to Bletchley Park, the wartime station of GCCS.[23]

Turing had something of a reputation for eccentricity at Bletchley Park. Jack Good, a cryptanalyst who worked with him, is quoted by Ronald Lewin as having said of Turing:

in the first week of June each year he would get a bad attack of hay fever, and he would cycle to the office wearing a service gas mask to keep the pollen off. His bicycle had a fault: the chain would come off at regular intervals. Instead of having it mended he would count the number of times the pedals went round and would get off the bicycle in time to adjust the chain by hand. Another of his eccentricities is that he chained his mug to the radiator pipes to prevent it being stolen.[24]

Turing–Welchman bombe

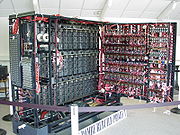

Within weeks of arriving at Bletchley Park,[23] Turing had specified an electromechanical machine which could help break Enigma faster than bomba from 1932, the bombe, named after and building upon the original Polish-designed bomba. The bombe, with an enhancement suggested by mathematician Gordon Welchman, became one of the primary tools, and the major automated one, used to attack Enigma-protected message traffic.

Jack Good opined:

Turing's most important contribution, I think, was of part of the design of the bombe, the cryptanalytic machine. He had the idea that you could use, in effect, a theorem in logic which sounds to the untrained ear rather absurd; namely that from a contradiction, you can deduce everything.[25]

The bombe searched for possibly correct settings used for an Enigma message (i.e., rotor order, rotor settings, etc.), and used a suitable "crib": a fragment of probable plaintext. For each possible setting of the rotors (which had of the order of 1019 states, or 1022 for the four-rotor U-boat variant),[26] the bombe performed a chain of logical deductions based on the crib, implemented electrically. The bombe detected when a contradiction had occurred, and ruled out that setting, moving onto the next. Most of the possible settings would cause contradictions and be discarded, leaving only a few to be investigated in detail. Turing's bombe was first installed on 18 March 1940.[27] More than two hundred bombes were in operation by the end of the war.[28]

Turing decided to tackle the particularly difficult problem of German naval Enigma "because no one else was doing anything about it and I could have it to myself".[30] In December 1939, Turing solved the essential part of the naval indicator system, which was more complex than the indicator systems used by the other services.[30][31] The same night that he solved the naval indicator system, he conceived the idea of Banburismus, a Bayesian statistical technique to assist in breaking naval Enigma, "though I was not sure that it would work in practice, and was not in fact sure until some days had actually broken".[30] Banburismus could rule out certain orders of the Enigma rotors, reducing time needed to test settings on the bombes.

In 1941, Turing proposed marriage to Hut 8 co-worker Joan Clarke, a fellow mathematician, but their engagement was short-lived. After admitting his homosexuality to his fiancée, who was reportedly "unfazed" by the revelation, Turing decided that he could not go through with the marriage.[32]

In July 1942, Turing devised a technique termed Turingismus or Turingery[33] for use against the Lorenz cipher used in the Germans' new Geheimschreiber machine ("secret writer") which was one of those codenamed "Fish". He also introduced the Fish team to Tommy Flowers who, under the guidance of Max Newman, went on to build the Colossus computer, the world's first programmable digital electronic computer, which replaced simpler prior machines (including the "Heath Robinson") and whose superior speed allowed the brute-force decryption techniques to be applied usefully to the daily changing cyphers.[34] A frequent misconception is that Turing was a key figure in the design of Colossus; this was not the case.[35]

Turing travelled to the United States in November 1942 and worked with U.S. Navy cryptanalysts on Naval Enigma and bombe construction in Washington, and assisted at Bell Labs with the development of secure speech devices. He returned to Bletchley Park in March 1943. During his absence, Hugh Alexander had officially assumed the position of head of Hut 8, although Alexander had been de facto head for some time—Turing having little interest in the day-to-day running of the section. Turing became a general consultant for cryptanalysis at Bletchley Park.

There should be no question in anyone's mind that Turing's work was the biggest factor in Hut 8's success. In the early days he was the only cryptographer who thought the problem worth tackling and not only was he primarily responsible for the main theoretical work within the Hut but he also shared with Welchman and Keen the chief credit for the invention of the Bombe. It is always difficult to say that anyone is absolutely indispensable but if anyone was indispensable to Hut 8 it was Turing. The pioneer's work always tends to be forgotten when experience and routine later make everything seem easy and many of us in Hut 8 felt that the magnitude of Turing's contribution was never fully realised by the outside world.—Alexander, Sir C. Hugh O'D. Cryptographic History of Work on the German Naval Enigma. The National Archives, Kew, Reference HW 25/1.

While working at Bletchley, Turing, a talented long-distance runner, occasionally ran the 40 miles (64 km) to London when he was needed for high-level meetings.[36]

In the latter part of the war he moved to work at Hanslope Park, where he further developed his knowledge of electronics with the assistance of engineer Donald Bailey. Together they undertook the design and construction of a portable secure voice communications machine codenamed Delilah.[37] It was intended for different applications, lacking capability for use with long-distance radio transmissions, and in any case, Delilah was completed too late to be used during the war. Though Turing demonstrated it to officials by encrypting/decrypting a recording of a Winston Churchill speech, Delilah was not adopted for use. Turing also consulted with Bell Labs on the development of SIGSALY, a secure voice system that was used in the later years of the war.

In 1945, Turing was awarded the OBE for his wartime services, but his work remained secret for many years. A biography published by the Royal Society shortly after his death recorded:

Three remarkable papers written just before the war, on three diverse mathematical subjects, show the quality of the work that might have been produced if he had settled down to work on some big problem at that critical time. For his work at the Foreign Office he was awarded the OBE.—Newman, M. H. A. (1955). Alan Mathison Turing. Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, 1955, Volume 1. The Royal Society.

Early computers and the Turing test

From 1945 to 1947 he lived in Church Sreet, Hampton[38] and was at the National Physical Laboratory, where he worked on the design of the ACE (Automatic Computing Engine). He presented a paper on 19 February 1946, which was the first detailed design of a stored-program computer.[39] Although ACE was a feasible design, the secrecy surrounding the wartime work at Bletchley Park led to delays in starting the project and he became disillusioned. In late 1947 he returned to Cambridge for a sabbatical year. While he was at Cambridge, the Pilot ACE was built in his absence. It executed its first program on 10 May 1950.

In 1948 he was appointed Reader in the Mathematics Department at Manchester. In 1949 he became deputy director of the computing laboratory at the University of Manchester, and worked on software for one of the earliest stored-program computers—the Manchester Mark 1. During this time he continued to do more abstract work, and in "Computing machinery and intelligence" (Mind, October 1950), Turing addressed the problem of artificial intelligence, and proposed an experiment now known as the Turing test, an attempt to define a standard for a machine to be called "intelligent". The idea was that a computer could be said to "think" if it could fool an interrogator into thinking that the conversation was with a human. In the paper, Turing suggested that rather than building a program to simulate the adult mind, it would be better rather to produce a simpler one to simulate a child's mind and then to subject it to a course of education. A form of the Turing test is widely used on the Internet; the CAPTCHA test is intended to determine whether the user is a human or a computer.

In 1948, Turing, working with his former undergraduate colleague, D. G. Champernowne, began writing a chess program for a computer that did not yet exist. In 1952, lacking a computer powerful enough to execute the program, Turing played a game in which he simulated the computer, taking about half an hour per move. The game was recorded.[40] The program lost to Turing's colleague Alick Glennie, although it is said that it won a game against Champernowne's wife.

His Turing test was a significant and characteristically provocative and lasting contribution to the debate regarding artificial intelligence, which continues after more than half a century [41].

Pattern formation and mathematical biology

Turing worked from 1952 until his death in 1954 on mathematical biology, specifically morphogenesis. He published one paper on the subject called "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis" in 1952, putting forth the Turing hypothesis of pattern formation.[42] His central interest in the field was understanding Fibonacci phyllotaxis, the existence of Fibonacci numbers in plant structures. He used reaction–diffusion equations which are now central to the field of pattern formation. Later papers went unpublished until 1992 when Collected Works of A.M. Turing was published. His contribution is now considered to be a seminal piece of work in this field.[43]

Conviction for indecency

In January 1952, Turing met Arnold Murray outside a cinema in Manchester. After a lunch date, Turing invited Murray to spend the weekend with him at his house, an invitation which Murray accepted although he did not show up. The pair met again in Manchester the following Monday, when Murray agreed to accompany Turing to the latter's house. A few weeks later Murray visited Turing's house again, and apparently spent the night there.[44]

After Murray helped an accomplice to break into his house, Turing reported the crime to the police. During the investigation, Turing acknowledged a sexual relationship with Murray. Homosexual acts were illegal in the United Kingdom at that time,[7] and so both were charged with gross indecency under Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885, the same crime for which Oscar Wilde had been convicted more than fifty years earlier.[45]

Turing was given a choice between imprisonment or probation conditional on his agreement to undergo hormonal treatment designed to reduce libido. He accepted chemical castration via oestrogen hormone injections.[46]

Turing's conviction led to the removal of his security clearance, and barred him from continuing with his cryptographic consultancy for GCHQ. At the time, there was acute public anxiety about spies and homosexual entrapment by Soviet agents,[47] because of the recent exposure of the first two members of the Cambridge Five, Guy Burgess and Donald Maclean, as KGB double agents. Turing was never accused of espionage but, as with all who had worked at Bletchley Park, was prevented from discussing his war work.[48]

Death

On 8 June 1954, Turing's cleaner found him dead; he had died the previous day. A post-mortem examination established that the cause of death was cyanide poisoning. When his body was discovered an apple lay half-eaten beside his bed, and although the apple was not tested for cyanide,[49] it is speculated that this was the means by which a fatal dose was delivered. An inquest determined that he had committed suicide, and he was cremated at Woking crematorium on 12 June 1954.

Turing's mother argued strenuously that the ingestion was accidental, caused by her son's careless storage of laboratory chemicals. Biographer Andrew Hodges suggests that Turing may have killed himself in an ambiguous way quite deliberately, to give his mother some plausible deniability.[50] Others suggest that Turing was re-enacting a scene from the 1937 film Snow White, his favourite fairy tale, pointing out that he took "an especially keen pleasure in the scene where the Wicked Witch immerses her apple in the poisonous brew."[51]

Epitaph

Hyperboloids of wondrous Light

Rolling for aye through Space and Time

Harbour those Waves which somehow Might

Play out God's holy pantomime—Turing, A. M. (1954). Postcard to Robin Gandy. Turing Digital Archive, AMT/D/4 image 16, http://www.turingarchive.org/.

Recognition and tributes

Since 1966, the Turing Award has been given annually by the Association for Computing Machinery to a person for technical contributions to the computing community. It is widely considered to be the computing world's highest honour, equivalent to the Nobel Prize.[52]

Breaking the Code is a 1986 play by Hugh Whitemore about Alan Turing. The play ran in London's West End beginning in November 1986 and on Broadway from 15 November 1987 to 10 April 1988. There was also a 1996 BBC television production. In all cases, Derek Jacobi played Turing. The Broadway production was nominated for three Tony Awards including Best Actor in a Play, Best Featured Actor in a Play, and Best Direction of a Play, and for two Drama Desk Awards, for Best Actor and Best Featured Actor. Turing was one of four mathematicians examined in the 2008 BBC documentary entitled "Dangerous Knowledge".[53]

On 23 June 1998, on what would have been Turing's 86th birthday, Andrew Hodges, his biographer, unveiled an official English Heritage Blue Plaque at his birthplace and childhood home in Warrington Crescent, London, now the Colonnade hotel.[54][55] To mark the 50th anniversary of his death, a memorial plaque was unveiled on 7 June 2004 at his former residence, Hollymeade, in Wilmslow, Cheshire.[56]

On 13 March 2000, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines issued a set of stamps to celebrate the greatest achievements of the twentieth century, one of which carries a recognisable portrait of Turing against a background of repeated 0s and 1s, and is captioned: "1937: Alan Turing's theory of digital computing".

On 28 October 2004, a bronze statue of Alan Turing sculpted by John W Mills was unveiled at the University of Surrey in Guildford, marking the 50th anniversary of Turing's death; it portrays him carrying his books across the campus.[57]

In 2006, Boston Pride named Turing their Honorary Grand Marshal.[58]

A 1.5-ton, life-size statue of Turing was unveiled on 19 June 2007 at Bletchley Park. Built from approximately half a million pieces of Welsh slate, it was sculpted by Stephen Kettle, having been commissioned by the late American billionaire Sidney Frank.[59]

Turing has been honoured in various ways in Manchester, the city where he worked towards the end of his life. In 1994, a stretch of the A6010 road (the Manchester city intermediate ring road) was named Alan Turing Way. A bridge carrying this road was widened, and carries the name Alan Turing Bridge. A statue of Turing was unveiled in Manchester on 23 June 2001. It is in Sackville Park, between the University of Manchester building on Whitworth Street and the Canal Street gay village. The memorial statue, depicts the "father of Computer Science" sitting on a bench at a central position in the park. The statue was unveiled on Turing's birthday.

Turing is shown holding an apple—a symbol classically used to represent forbidden love, the object that inspired Isaac Newton's theory of gravitation, and the means of Turing's own death. The cast bronze bench carries in relief the text 'Alan Mathison Turing 1912–1954', and the motto 'Founder of Computer Science' as it would appear if encoded by an Enigma machine: 'IEKYF ROMSI ADXUO KVKZC GUBJ'.

A plinth at the statue's feet says 'Father of computer science, mathematician, logician, wartime codebreaker, victim of prejudice'. There is also a Bertrand Russell quotation saying 'Mathematics, rightly viewed, possesses not only truth, but supreme beauty—a beauty cold and austere, like that of sculpture.' The sculptor buried his old Amstrad computer, which was an early popular home computer, under the plinth, as a tribute to "the godfather of all modern computers".[60]

In 1999, Time Magazine named Turing as one of the 100 Most Important People of the 20th Century for his role in the creation of the modern computer, and stated: "The fact remains that everyone who taps at a keyboard, opening a spreadsheet or a word-processing program, is working on an incarnation of a Turing machine."[1]

In 2002, Turing was ranked twenty-first on the BBC nationwide poll of the 100 Greatest Britons.[61]

The logo of Apple computers is often erroneously referred to as a tribute to Alan Turing, with the bite mark a reference to his method of suicide.[62] Both the designer of the logo[63] and the company deny that there is any homage to Turing in the design of the logo.[64]

In 2010, actor/playwright Jade Esteban Estrada portrayed Turing in the solo musical, "ICONS: The Lesbian and Gay History of the World, Vol. 4."

Government apology

In August 2009, John Graham-Cumming started a petition urging the British Government to posthumously apologise to Alan Turing for prosecuting him as a homosexual.[65][66] The petition received thousands of signatures.[67][68] Prime Minister Gordon Brown acknowledged the petition, releasing a statement on 10 September 2009 apologising and describing Turing's treatment as "appalling":[67][69]

Thousands of people have come together to demand justice for Alan Turing and recognition of the appalling way he was treated. While Turing was dealt with under the law of the time and we can't put the clock back, his treatment was of course utterly unfair and I am pleased to have the chance to say how deeply sorry I and we all are for what happened to him ... So on behalf of the British government, and all those who live freely thanks to Alan's work I am very proud to say: we're sorry, you deserved so much better.[67]

Tributes by universities

A celebration of Turing's life and achievements arranged by the British Logic Colloquium and the British Society for the History of Mathematics was held on 5 June 2004 at the University of Manchester; the Alan Turing Institute was initiated in the university that summer.

- Istanbul Bilgi University organises an annual conference on the theory of computation called "Turing Days".[70]

- The University of Texas at Austin has an honours computer science programme named the Turing Scholars.[71]

- The Department of Computer Science at Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, the Polytechnic University of Puerto Rico, Los Andes University in Bogotá, Colombia, King's College, Cambridge and Bangor University in Wales have computer laboratories named after Turing.

- The University of Manchester, The Open University, Oxford Brookes University and Aarhus University (in Århus, Denmark) all have buildings named after Turing.

- Alan Turing Road in the Surrey Research Park is named for Alan Turing.

- Carnegie Mellon University has a granite bench, situated in The Hornbostel Mall, with the name "A. M. Turing" carved across the top, "Read" down the left leg, and "Write" down the other.

- The École Internationale des Sciences du Traitement de l'Information has named its recently acquired third building "Turing".

See also

- Turing degree

- Turing switch

- Unorganized machine

- Alan Turing Year

- Good–Turing frequency estimation

- Turing machine examples

- Turing test

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Alan Turing – Time 100 People of the Century". Time Magazine. http://205.188.238.181/time/time100/scientist/profile/turing.html. "The fact remains that everyone who taps at a keyboard, opening a spreadsheet or a word-processing program, is working on an incarnation of a Turing machine."

- ↑ A.M. Turing, "The Chemical Basis of Morphogenesis", Philosophical Transactions of The Royal Society of London, series B, volume 237, pages 37–72, 1952.

- ↑ "PM apology after Turing petition". BBC News. 11 September 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/8249792.stm.

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 5

- ↑ "London Blue Plaques". English-Heritage.org.uk. http://www.english-heritage.org.uk/server/show/nav.001002006005/chooseLetter/T. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ↑ Plaque #381 on Open Plaques.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Hodges, Andrew (1983). Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 5. ISBN 0-671-49207-1.

- ↑ "The Alan Turing Internet Scrapbook". http://www.turing.org.uk/turing/scrapbook/memorial.html. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- ↑ Jones, G. James (11 December 2001). "Alan Turing – Towards a Digital Mind: Part 1". System Toolbox. http://www.systemtoolbox.com/article.php?history_id=3. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ↑ Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1985). Metamagical Themas: Questing for the Essence of Mind and Pattern. Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04566-9. OCLC 230812136.

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 26

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 34

- ↑ ** Teuscher, Christof (ed.) (2004). Alan Turing: Life and Legacy of a Great Thinker. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-20020-7. OCLC 62339998 53434737 62339998.

- ↑ Paul Gray, "Alan Turing", Time Magazine's Most Important People of the Century, p.2 [1]

- ↑ http://www.turing.org.uk/turing/scrapbook/spirit.html

- ↑ See Section 3 of John Aldrich, "England and Continental Probability in the Inter-War Years", Journal Electronique d'Histoire des Probabilités et de la Statistique, vol. 5/2 [2]

- ↑ Turing, A.M. (1936). "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 42: pp. 230–65. 1937. doi:10.1112/plms/s2-42.1.230. http://www.comlab.ox.ac.uk/activities/ieg/e-library/sources/tp2-ie.pdf. (and Turing, A.M. (1938). "On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem: A correction". Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society 43: pp. 544–6. 1937. doi:10.1112/plms/s2-43.6.544.)

- ↑ College Kid Proves That Wolfram’s Turing Machine is the Simplest Universal Computer Wired 24 Oct 2007

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 138

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 152

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, pp. 153–154

- ↑ Jack Copeland, "Colossus and the Dawning of the Computer Age", p. 352 in Action This Day, 2001

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Copeland, 2006 p. 378

- ↑ Lewin (1978) p. 57

- ↑ "The Men Who Cracked Enigma", Episode 4 in the UKTV History Channel documentary series "Heroes of World War II"

- ↑ Professor Jack Good in "The Men Who Cracked Enigma", 2003: with his caveat: "if my memory is correct"

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 191.

- ↑ Copeland, Jack; Diane Proudfoot (May 2004). "Alan Turing, Codebreaker and Computer Pioneer". http://www.alanturing.net/turing_archive/pages/Reference%20Articles/codebreaker.html. Retrieved 27 July 2007.

- ↑ "Bletchley Park Unveils Statue Commemorating Alan Turing". http://www.bletchleypark.org.uk/news/docview.rhtm/454075. Retrieved 30 June 2007.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Mahon 1945, p. 14

- ↑ Leavitt 2007, pp. 184–186

- ↑ Leavitt 2007, pp. 176–178

- ↑ Copeland, 2006, p. 380

- ↑ Copeland, 2006, p. 72.

- ↑ Copeland, 2006, pp. 382, 383.

- ↑ Bodyguard of Lies, by Anthony Cave Brown, 1975.

- ↑ Hodges, 1983, p. 270

- ↑ Plaque #1619 on Open Plaques.

- ↑ Copeland, 2006, p. 108.

- ↑ Alan Turing vs Alick Glennie (1952) "Turing Test"

- ↑ Saygin, A.P., Cicekli, I., & Akman, V. (2000) Turing Test: 50 years later. Minds and Machines, Vol. 10, pp 463-518.

- ↑ "Control Mechanism For Biological Pattern Formation Decoded" in ScienceDaily (30 Nov. 2006)

- ↑ [3]"Turing's Last, Lost work"

- ↑ Leavitt 2007, p. 266

- ↑ Leavitt 2007, p. 268

- ↑ Turing, Alan (1912–1954)

- ↑ Leavitt 2007, p. 269

- ↑ Copeland 2006, p. 143

- ↑ Hodges 1983, p. 488

- ↑ Hodges 1983, pp. 488, 489

- ↑ Leavitt 2007, p. 140

- ↑ Steven Geringer (27 July 2007). "ACM'S Turing Award Prize Raised To $250,000". ACM press release. http://www.acm.org/press-room/news-releases-2007/turingaward/. Retrieved 16 October 2008.

- ↑ "Dangerous Knowledge". BBC. 11 June 2008. http://www.bbc.co.uk/bbcfour/documentaries/features/dangerous-knowledge.shtml/. Retrieved 25 September 2009.

- ↑ "Unveiling the official Blue Plaque on Alan Turing's Birthplace". http://www.turing.org.uk/bio/oration.html. Retrieved 26 September 2006.

- ↑ "About this Plaque – Alan Turing". Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20071013143212/http://www.blueplaque.com/detail.php?plaque_id=348. Retrieved 25 September 2006.

- ↑ Plaque #3276 on Open Plaques.

- ↑ "The Earl of Wessex unveils statue of Alan Turing". http://portal.surrey.ac.uk/press/oct2004/281004a/. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ↑ "Honorary Grand Marshal". http://www.bostonpride.org/honorarymarshal.php. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ↑ Bletchley Park Unveils Statue Commemorating Alan Turing, Bletchley Park press release, 20 June 2007

- ↑ see "Computer buried in tribute to genius". Manchester Evening News. 15 June 2001. http://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/s/27/27595_computer_buried_in_tribute_to_genius.html. Retrieved 23 June 2009.

- ↑ "100 great British heroes". BBC News. 21 August 2002. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/2208671.stm.

- ↑ "Logos that became legends: Icons from the world of advertising". The Independent (London: www.independent.co.uk). 4 January 2008. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/media/logos-that-became-legends-icons-from-the-world-of-advertising-768077.html. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ↑ "Interview with Rob Janoff, designer of the Apple logo". creativebits.org. http://creativebits.org/interview/interview_rob_janoff_designer_apple_logo. Retrieved 14 September 2009.

- ↑ Leavitt 2007, p. 280

- ↑ Thousands call for Turing apology. BBC News. 31 August 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/8226509.stm. Retrieved 31 August 2009.

- ↑ Petition seeks apology for Enigma code-breaker Turing. CNN. 01 September 2009. http://www.cnn.com/2009/WORLD/europe/09/01/alan.turing.petition/index.html. Retrieved 1 September 2009.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 "Treatment of Alan Turing was "appalling"". Number10.gov.uk. 10 September 2009. http://www.number10.gov.uk/Page20571.

- ↑ The petition was only open to UK citizens.

- ↑ "PM apology after Turing petition". BBC News. 11 September 2009. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/8249792.stm. Retrieved 11 September 2009.

- ↑ "Turing Days @ İstanbul Bilgi University". http://cs.bilgi.edu.tr/pages/turing_days/. Retrieved 10 February 2007.

- ↑ "Turing Scholars Program at the University of Texas at Austin". http://www.cs.utexas.edu/academics/undergraduate/honors/turing/. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

References

- Levin, Janna (2006). A Madman Dreams of Turing Machines. New York, New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-1-4000-3240-2

- Agar, Jon (2002). The Government Machine. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-01202-2

- Beniger, James (1986). The Control Revolution: Technological and Economic Origins of the Information Society. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-16986-7

- Bodanis, David (2005). Electric Universe: How Electricity Switched on the Modern World. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-307-33598-4. OCLC 61684223.

- Campbell-Kelly, Martin (ed.) (1994). Passages in the Life of a Philosopher. London: William Pickering. ISBN 0-8135-2066-5

- Campbell-Kelly, Martin, and Aspray, William (1996). Computer: A History of the Information Machine. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-02989-2

- Ceruzzi, Paul (1998). A History of Modern Computing. Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53169-0

- Chandler, Alfred (1977). The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press. ISBN 0-674-94052-0

- Copeland, B. Jack (2004). "Colossus: Its Origins and Originators". IEEE Annals of the History of Computing 26 (4): 38–45. doi:10.1109/MAHC.2004.26.

- Copeland, B. Jack (ed.) (2004). The Essential Turing. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-825079-7. OCLC 224173329 48931664 57434580 57530137 59399569 156728127 224173329 48931664 57434580 57530137 59399569.

- Copeland (ed.), B. Jack (2005). Alan Turing's Automatic Computing Engine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-856593-3. OCLC 56539230 224640979 56539230.

- Copeland, B. Jack (2006). Colossus: The secrets of Bletchley Park's code-breaking computers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-284055-4.

- Edwards, Paul N (1996). The Closed World. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-55028-8

- Hodges, Andrew (1983). Alan Turing: The Enigma of Intelligence. London: Burnett Books. ISBN 0-04-510060-8.

- Hochhuth, Rolf. Alan Turing

- Leavitt, David (2007). The Man Who Knew Too Much; Alan Turing and the invention of the computer. Phoenix. ISBN 978-0-7538-2200-5.

- Lewin, Ronald (1978). Ultra Goes to War: The Secret Story. Classic Military History (Classic Penguin ed.). London, England: Hutchinson & Co (published 2001). ISBN 978-1566492317

- Lubar, Steven (1993). Infoculture. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-57042-5.

- Mahon, A.P. (1945). The History of Hut Eight 1939–1945. UK National Archives Reference HW 25/2. http://www.ellsbury.com/hut8/hut8-000.htm. Retrieved 10 December 2009

- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Alan Mathison Turing", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Turing.html.

- Petzold, Charles (2008). "The Annotated Turing: A Guided Tour through Alan Turing's Historic Paper on Computability and the Turing Machine". Indianapolis: Wiley Publishing. ISBN 978-0-470-22905-7

- Smith, Roger (1997). Fontana History of the Human Sciences. London: Fontana.

- Weizenbaum, Joseph (1976). Computer Power and Human Reason. London: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 0-7167-0463-3

- Williams, Michael R. (1985). A History of Computing Technology. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-8186-7739-2

- Yates, David M. (1997). Turing's Legacy: A history of computing at the National Physical Laboratory 1945–1995. London: London Science Museum. ISBN 0-901805-94-7. OCLC 40624091 123794619 40624091.

- Turing's mother, Sara Turing, who survived him by many years, wrote a biography of her son glorifying his life. Published in 1959, it could not cover his war work; scarcely 300 copies were sold (Sara Turing to Lyn Newman, 1967, Library of St John's College, Cambridge). The six-page foreword by Lyn Irvine includes reminiscences and is more frequently quoted.

- Breaking the Code is a 1986 play by Hugh Whitemore, telling the story of Turing's life and death. In the original West End and Broadway runs, Derek Jacobi played Turing and he recreated the role in a 1997 television film based on the play made jointly by the BBC and WGBH, Boston. The play is published by Amber Lane Press, Oxford. ASIN: B000B7TM0Q

External links

- Alan Turing site maintained by Andrew Hodges including a short biography

- AlanTuring.net – Turing Archive for the History of Computing by Jack Copeland

- The Turing Archive – contains scans of some unpublished documents and material from the Kings College, Cambridge archive

- Alan Turing at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- Alan Turing – Towards a Digital Mind: Part 1

- Alan Turing at Find a Grave

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry

- Time 100: Alan Turing

- Alan Turing in the RKBExplorer

- The Mind and the Computing Machine a 1949 discussion of Alan Turing and others, The Rutherford Journal

- Alan Turing Year website

- CiE 2012: Turing Centenary Conference website

- Visual Turing website

Papers

- An extensive list of Turing's papers, reports and lectures, plus translated versions and collections

- Turing, Alan (October 1950), "Computing Machinery and Intelligence", Mind LIX (236): 433–460, doi:10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433, ISSN 0026-4423, http://loebner.net/Prizef/TuringArticle.html, retrieved 2008-08-18

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||