Trumpet

B♭ trumpet |

|

| Brass instrument | |

|---|---|

| Classification |

Brass |

| Hornbostel-Sachs classification | 423.233 (Valved aerophone sounded by lip movement) |

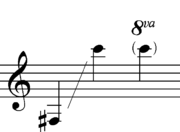

| Playing range | |

Written range:

|

|

| Related instruments | |

| Flugelhorn, Cornet, Bugle, Natural trumpet, Bass trumpet, Post horn, Roman tuba, Bucina, Shofar, Conch, Lur, Didgeridoo, Piccolo trumpet, Baritone horn, Pocket trumpet |

|

The trumpet is the musical instrument with the highest register in the brass family. Trumpets are among the oldest musical instruments,[1] dating back to at least 1500 BCE. They are constructed of brass tubing bent twice into an oblong shape, and are played by blowing air through closed lips, producing a "buzzing" sound which starts a standing wave vibration in the air column inside the trumpet.

There are several types of trumpet; the most common is a transposing instrument pitched in B♭. The tube length of the most common B-trumpet is about 134 cm. The predecessors to trumpets did not have valves, but modern trumpets have either three piston valves or three rotary valves. Each valve increases the length of tubing when engaged, thereby lowering the pitch.

The trumpet is used in many forms of music, including classical music and jazz.

A musician who plays the trumpet is called a trumpet player or trumpeter.

Contents |

History

The earliest trumpets date back to 1500 BCE and earlier. The bronze and silver trumpets from Tutankhamun's grave in Egypt, bronze lurs from Scandinavia, and metal trumpets from China date back to this period.[2] Trumpets from the Oxus civilization (3rd millennium BCE) of Central Asia have decorated swellings in the middle, yet are made out of one sheet of metal, which is considered a technical wonder.[3] The Moche people of ancient Peru depicted trumpets in their art going back to 300 CE. [4] The earliest trumpets were signaling instruments used for military or religious purposes, rather than music in the modern sense;[5] and the modern bugle continues this signaling tradition.

In medieval times, trumpet playing was a guarded craft, its instruction occurring only within highly selective guilds. The trumpet players were often among the most heavily guarded members of a troop, as they were relied upon to relay instructions to other sections of the army.

Improvements to instrument design and metal making in the late Middle Ages and Renaissance led to an increased usefulness of the trumpet as a musical instrument. The natural trumpets of this era consisted of a single coiled tube without valves and therefore could only produce the notes of a single overtone series. Changing keys required the player to swap out the crooks of the instrument. The development of the upper, "clarino" register by specialist trumpeters—notably Cesare Bendinelli—would lend itself well to the Baroque era, also known as the "Golden Age of the natural trumpet." During this period, a vast body of music was written for virtuoso trumpeters. The art was revived in the mid-20th century and natural trumpet playing is again a thriving art around the world. Most successful players nowadays use a version of the natural trumpet dubbed the baroque trumpet which is fitted with one or more vent holes to aid in correcting out-of-tune notes in the harmonic series.

The melody-dominated homophony of the classical and romantic periods relegated the trumpet to a secondary role by most major composers owing to the limitations of the natural trumpet. Berlioz wrote in 1844:

Notwithstanding the real loftiness and distinguished nature of its quality of tone, there are few instruments that have been more degraded (than the trumpet). Down to Beethoven and Weber, every composer - not excepting Mozart - persisted in confining it to the unworthy function of filling up, or in causing it to sound two or three commonplace rhythmical formulae.[6]

The attempt to give the trumpet more chromatic freedom in its range saw the development of the keyed trumpet, but this was a largely unsuccessful venture due to the poor quality of its sound.

Although the impetus for a tubular valve began as early as 1793, it was not until 1818 that Friedrich Bluhmel and Heinrich Stölzel made a joint patent application for the box valve as manufactured by W. Schuster. The symphonies of Mozart, Beethoven, and as late as Brahms, were still played on natural trumpets. Crooks and shanks (removable tubing of various lengths) as opposed to keys or valves were standard, notably in France, into the first part of the 20th century. As a consequence of this late development of the instrument's chromatic ability, the repertoire for the instrument is relatively small compared to other instruments. The 20th century saw an explosion in the amount and variety of music written for the trumpet.

Construction

The trumpet is constructed of brass tubing bent twice into an oblong shape.[7] The trumpet and trombone share a roughly cylindrical bore which results in a bright, loud sound. The bore is actually a complex series of tapers, smaller at the mouthpiece receiver and larger just before the flare of the bell begins; careful design of these tapers is critical to the intonation of the instrument. By comparison, the cornet and flugelhorn have conical bores and produce a more mellow tone. Bore sizes generally range from 0.430 to 0.472 inches and are usually listed as medium, medium large and large from various manufactuers.

As with all brass instruments, sound is produced by blowing air through closed lips, producing a "buzzing" sound into the mouthpiece and starting a standing wave vibration in the air column inside the trumpet. The player can select the pitch from a range of overtones or harmonics by changing the lip aperture and tension (known as the embouchure). The mouthpiece has a circular rim which provides a comfortable environment for the lips' vibration. Directly behind the rim is the cup, which channels the air into a much smaller opening (the back bore or shank) which tapers out slightly to match the diameter of the trumpet's lead pipe. The dimensions of these parts of the mouthpiece affect the timbre or quality of sound, the ease of playability, and player comfort. Generally, the wider and deeper the cup, the darker the sound and timbre.

Modern trumpets have three (or infrequently four) piston valves, each of which increases the length of tubing when engaged, thereby lowering the pitch. The first valve lowers the instrument's pitch by a whole step (2 semitones), the second valve by a half step (1 semitone), and the third valve by one-and-a-half steps (3 semitones). When a fourth valve is present, as with some piccolo trumpets, it lowers the pitch a perfect fourth (5 semitones). Used singly and in combination these valves make the instrument fully chromatic, i.e., able to play all twelve pitches of classical music.

The pitch of the trumpet can also be raised or lowered by the use of the tuning slide. Pulling the slide out flattens the pitch, pushing in the slide will make the horn play sharper. To overcome the problems of intonation and reduce the use of the slide, Renold Schilke designed the tuning-bell trumpet. Removing the usual brace between the bell and a valve body allows the use of a sliding bell; the player may then tune the horn with the bell while leaving the slide pushed in, or nearly so, thereby improving intonation and overall response.[8]

The sound is projected outward via the bell. The trumpet is also available in a variety of bell materials ranging from yellow-brass, red-brass and copper. The darker brass produces a warmer tonal quality.

A trumpet becomes a closed tube when the player presses it to the lips; therefore, the instrument only naturally produces every other overtone of the harmonic series. The shape of the bell is what allows the missing overtones to be heard.[9] Most notes in the series are slightly off key, and modern trumpets have slide mechanisms built in to compensate.

Types of trumpets

The most common type is the B♭ trumpet, but low F, C, D, E♭, E, G and A trumpets are also available. The C trumpet is most common in American orchestral playing, where it is used alongside the B♭ trumpet. Its slightly smaller size gives it a brighter, more lively sound. Because music written for early trumpets required the use of a different trumpet for each key — they did not have valves and therefore were not chromatic — and also because a player may choose to play a particular passage on a different trumpet from the one indicated on the written music, orchestra trumpet players are generally adept at transposing music at sight, sometimes playing music written for the B♭ trumpet on the C trumpet, and vice versa.

The standard trumpet range extends from the written F♯ immediately below Middle C up to about three octaves higher. Traditional trumpet repertoire rarely calls for notes beyond this range, and the fingering tables of most method books peak at the C (high C) two octaves above middle C. Several trumpeters have achieved fame for their proficiency in the extreme high register, among them Lew Soloff, Andrea Tofanelli, Bill Chase, Maynard Ferguson, Roger Ingram, Wayne Bergeron, Anthony Gorruso, Dizzy Gillespie, Jon Faddis, Cat Anderson, James Morrison, Doc Severinsen and Arturo Sandoval. It is also possible to produce pedal tones below the low F♯, which is a device commonly employed in contemporary repertoire for the instrument.

The smallest trumpets are referred to as piccolo trumpets. The most common of these are built to play in both B♭ and A, with separate leadpipes for each key. The tubing in the B♭ piccolo trumpet is one-half the length of that in a standard B♭ trumpet. Piccolo trumpets in G, F and C are also manufactured, but are rarer. Many players use a smaller mouthpiece on the piccolo trumpet, which requires a different sound production technique from the B♭ trumpet and can limit endurance. Almost all piccolo trumpets have four valves instead of the usual three — the fourth valve lowers the pitch, usually by a fourth, to facilitate the playing of lower notes. Maurice André, Håkan Hardenberger, and Wynton Marsalis are some well-known piccolo trumpet players.

Trumpets pitched in the key of low G are also called sopranos, or soprano bugles, after their adaptation from military bugles. Traditionally used in drum and bugle corps, sopranos have featured both rotary valves and piston valves.

The bass trumpet is usually played by a trombone player, being at the same pitch. Bass trumpet is played with a shallower trombone mouthpiece, and music for it is written in treble clef.

The modern slide trumpet is a B♭ trumpet that has a slide instead of valves. It is similar to a soprano trombone. The first slide trumpets emerged during the Renaissance, predating the modern trombone, and are the first attempts to increase chromaticism on the instrument. Slide trumpets were the first trumpets allowed in the Christian church.[10]

The historical slide trumpet was probably first developed in the late fourteenth century for use in alta capella wind bands. Deriving from early straight trumpets, the Renaissance slide trumpet was essentially a natural trumpet with a sliding leadpipe. This single slide was rather awkward, as the entire corpus of the instrument moved, and the range of the slide was probably no more than a major third. Originals were probably pitched in D, to fit with shawms in D and G, probably at a typical pitch standard near A=466Hz. As no instruments from this period are known to survive, the details - and even the existence - of a Renaissance slide trumpet is a matter of some conjecture, and there continues to be some debate among scholars.[11]

Some slide trumpet designs saw use in England in the eighteenth century.[12]

The pocket trumpet is a compact B♭ trumpet. The bell is usually smaller than a standard trumpet and the tubing is more tightly wound to reduce the instrument size without reducing the total tube length. Its design is not standardized, and the quality of various models varies greatly. It can have a tone quality and projection unique in the trumpet world: a warm sound and a voice-like articulation. Unfortunately, since many pocket trumpet models suffer from poor design as well as cheap and sloppy manufacturing, the intonation, tone color and dynamic range of such instruments are severely hindered. Professional-standard instruments are, however, available. While they are not a substitute for the full-sized instrument, they can be useful in certain contexts.

There are also rotary-valve, or German, trumpets, as well as alto and Baroque trumpets.

The trumpet is often confused with its close relative, the cornet, which has a more conical tubing shape compared to the trumpet's more cylindrical tube. This, along with additional bends in the cornet's tubing, gives the cornet a slightly mellower tone, but the instruments are otherwise nearly identical. They have the same length of tubing and, therefore, the same pitch, so music written for cornet and trumpet is interchangeable. Another relative, the flugelhorn, has tubing that is even more conical than that of the cornet, and an even richer tone. It is sometimes augmented with a fourth valve to improve the intonation of some lower notes.

Playing

Fingering

On any modern trumpet, cornet, or flugelhorn, pressing the valves indicated by the numbers below will produce the written notes shown - "OPEN" means all valves up, "1" means first valve, "1-2" means first and second valve simultaneously and so on. The concert pitch which sounds depends on the transposition of the instrument. Engaging the fourth valve, if present, drops any of these pitches by a perfect fourth as well. Within each overtone series, the different pitches are attained by changing the embouchure, or lip-aperture size and "firmness". Standard fingerings above high C are the same as for the notes an octave below (C♯ is 1-2, D is 1, etc.)

Each overtone series on the trumpet begins with the first overtone - the fundamental of each overtone series can not be produced except as a pedal tone. Notes in parentheses are the sixth overtone, representing a pitch with a frequency of seven times that of the fundamental; while this pitch is close to the note shown, it is slightly flat relative to equal temperament, and use of those fingerings is generally avoided.

The fingering schema arises from the length of each valve's tubing (a longer tube produces a lower pitch). Valve "1" increases the tubing length enough to lower the pitch by one whole step, valve "2" by one half step, and valve "3" by one and a half steps. This scheme and the nature of the overtone series create the possibility of alternate fingerings for certain notes. For example, third-space "C" can be produced with no valves engaged (standard fingering) or with valves 2-3. Also, any note produced with 1-2 as its standard fingering can also be produced with valve 3 - each drops the pitch by 1-1/2 steps. Alternate fingerings may be used to improve facility in certain passages, or to aid in intonation. Extending the third valve slide when using the fingerings 1-3 or 1-2-3 further lowers the pitch slightly to improve intonation.

Extended technique

Yale trombone professor John Swallow noted that brass techniques expanded rapidly in the 20th century due to the innovations of jazz players. Contemporary music for the trumpet makes wide uses of extended trumpet techniques.

Flutter tonguing: The trumpeter rolls the tip of the tongue to produce a 'growling like' tone. It is achieved as if one were rolling an R in the Spanish language. This technique is widely employed by composers like Berio and Stockhausen.

Growling: While playing a note, clinching the back of the throat to partially obstruct the air, preventing it from flowing evenly. This creates a gargling sound, thus making a 'growling' sound from the bell. Utilized by many jazz players, not to be confused with flutter tonguing, where the tongue is 100% responsible for creating the sound desired.

Double tonguing: The player articulates using the syllables ta-ka ta-ka ta-ka

Triple tonguing: The same as double tonguing, but with the syllables ta-ta-ka ta-ta-ka ta-ta-ka. Also can be said with the syllables ta-ka-ta ta-ka-ta ta-ka-ta ta-ka-ta.

Doodle tongue: The trumpeter tongues so lightly that the articulation is almost indistinguishable.

Glissando: Trumpeters can slide between notes by depressing the valve halfway or changing the lip tension. Modern repertoire makes extensive use of this technique.

Vibrato: Vibrato is often regulated in contemporary repertoire through specific notation. Composers can call for everything from fast, slow or no vibrato to actual rhythmic patterns played with vibrato.

Pedal tone: Composers have written for two and a half octaves below the low F#, which is at the bottom of the standard range. Extreme low pedals are produced by slipping the lower lip out of the mouthpiece. The technique was pioneered famously by Bohumir Kryl.

Microtones: Composers such as Scelsi and Stockhausen have made wide use of the trumpet's ability to play microtonally. Some instruments are adapted with a 4th valve which allows for a quarter-tone step between each note.

Mute belt: Karlheinz Stockhausen pioneered the use of a mute belt, worn around the player's waist, to enable rapid mute changes during pieces. The belt allows the performer to make faster and quieter mute changes, as well as enabling the performer to move around the stage.

Valve tremolo: Many notes on the trumpet can be played in several different valve combinations. By alternating between valve combinations on the same note, a tremolo effect can be created. Berio makes extended use of this technique in his Sequenza X.

Noises: By hissing, clicking, or breathing through the instrument, the trumpet can be made to resonate in ways that do not sound at all like a trumpet. Noises sound a 1/2 step higher than they are notated, and often require amplification to be heard.

Preparation: Composers have called for the trumpet to be played under water, or with certain slides removed. It is increasingly common for all sorts of preparations to be requested of a trumpeter. Extreme preparations involve alternate constructions, such as double bells and extra valves.

Singing: Composers such as Robert Erickson and Mark-Anthony Turnage have called for trumpeters to sing during the course of a piece, often while playing. It is possible to create a multiphonic effect by singing and playing different notes simultaneously.

Double buzz: Trumpeters can produce more than one tone simultaneously by vibrating the two lips at different speeds. The interval produced is usually an octave or a fifth.

Lip Trill or Shake: By rapidly varying lip tension, but not changing the depressed valves, the pitch varies quickly between adjacent harmonics. These are usually done, and more straight-forward to execute, in the upper register.

Instruction and method books

One trumpet method publication of long-standing popularity is Jean-Baptiste Arban's Complete Conservatory Method for Trumpet (Cornet).[13] Other well-known method books include Technical Studies by Herbert L. Clarke,[14] Grand Method by Louis Saint-Jacome,Daily Drills and Technical Studie by Max Schlossberg, and methods by Claude Gordon and Charles Colin.[15] Vassily Brandt's Orchestral Etudes and Last Etudes[16] is used in many college and conservatory trumpet studios, containing drills on permutations of standard orchestral trumpet repertoire, transpositions, and other advanced material. A common method book for beginners is the Walter Beeler's Method for the Cornet, and there have been several instruction books written by virtuoso Allen Vizzutti. The Breeze Eazy method is sometimes used to teach younger students, as it includes general musical information.

Players

In early jazz, Louis Armstrong was well known for his virtuosity and his improvisations on the Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings. Miles Davis is widely considered one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century. His trumpet playing was distinctive, with a vocal, clear tone that has been imitated by many. The phrasing and sense of space in his solos have been models for generations of jazz musicians.[17] Dizzy Gillespie was a gifted improviser with an extremely high range, building on the style of Roy Eldridge but adding new layers of harmonic complexity. Gillespie had an enormous impact on virtually every subsequent trumpeter, both by the example of his playing and as a mentor to younger musicians. Maynard Ferguson came to prominence playing in Stan Kenton's orchestra, before forming his own band in 1957. He was noted for being able to play accurately in a remarkably high register.[18]

Notable classical trumpeters include Maurice André, Armando Ghitalla, Hakan Hardenberger, Adolph "Bud" Herseth, Wynton Marsalis, Malcolm McNab, Rafael Méndez, Maurice Murphy, Sergei Nakariakov, Charles Schlueter, Philip Smith, William Vacchiano, Allen Vizzutti, and Roger Voisin .

Among the other great modern jazz trumpet players are Nat Adderley, Bud Brisbois, Chet Baker, Clifford Brown, Doc Cheatham, Don Cherry, Kenny Dorham, Jon Faddis, Roy Hargrove, Tom Harrell, Freddie Hubbard, Roger Ingram, Harry James, Wynton Marsalis, Blue Mitchell, Lee Morgan, Fats Navarro, Nicholas Payton, Claudio Roditi, Wallace Roney, Arturo Sandoval, Bobby Shew, Doc Severinsen, Woody Shaw, Allen Vizzutti, and Snooky Young.

Notable natural trumpet players include Valentine Snow for whom Handel wrote several pieces and Gottfried Reiche who was Bach's chief trumpeter.

The American orchestral trumpet sound is largely attributable to Adolph "Bud" Herseth's 53-year tenure with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Though he was not as prolific a teacher as some of his peers, his widely recorded sound became the standard for American orchestras.

Musical pieces

Solos

The chromatic trumpet was first made in the late 1700s. The repertoire for the natural trumpet and cornetto is extensive. This music is commonly played on modern piccolo trumpets, although there are many highly proficient performers of the original instruments. This vast body of repertoire includes the music of Gabrieli, Monteverdi, Bach, Vivaldi and countless other composers. Because the overtone series doesn't allow stepwise movement until the upper register, the tessitura for this repertoire is very high.

Joseph Haydn's Trumpet Concerto was one of the first for a chromatic trumpet,[19] a fact shown off by some stepwise melodies played low in the instrument's range. Johann Hummel wrote the other great Trumpet Concerto of the Classical period, and these two pieces are the cornerstone of the instrument's repertoire. Written as they were in the infancy of the chromatic trumpet, they reflect only a minor advancement of the trumpet's musical language, with the Hummel's being the more adventurous piece by far.

In 1827, François Dauverné became the first musician to use the new F three valved trumpet in public performance.

In the 20th century, trumpet repertoire expanded rapidly as composers embraced the almost completely untapped potential of the modern trumpet.

See also

- Clarion

- List of trumpeters

- Muted trumpet

- Piccolo trumpet

- Keyed trumpet

- Guča trumpet festival - The world's largest trumpet festival

- Category:Compositions for trumpet

- Trumpet repertoire

References

Notes

- ↑ "History of the Trumpet". www.petrouska.com. http://www.petrouska.com/historyofthetrumpet.htm. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ↑ Edward Tarr, The Trumpet (Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press, 1988), 20-30.

- ↑ "Trumpet with a swelling decorated with a human head," Musée du Louvre, [1]

- ↑ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ↑ "Chicago Symphony Orchestra - Glossary - Brass instruments". www.cso.org. http://www.cso.org/main.taf?p=1,1,4,3. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ↑ Berlioz, Hector (1844). Treatise on modern Instrumentation and Orchestration. Edwin F. Kalmus, NY, 1948.

- ↑ "Trumpet, Brass Instrument". www.dsokids.com. http://www.dsokids.com/2001/dso.asp?PageID=162. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ↑ Dr. Colin Bloch (August 1978). "The Bell-Tuned Trumpet". http://www.dallasmusic.org/schilke/Tunable%20Bell%20Trumpets.html. Retrieved 25 February 2010.

- ↑ D. J. Blaikley, "How a Trumpet Is Made. I. The Natural Trumpet and Horn", The Musical Times, January 1, 1910, p. 15.

- ↑ Tarr

- ↑ "IngentaConnect More about Renaissance slide trumpets: fact or fiction?". www.ingentaconnect.com. http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/oup/earlyj/2004/00000032/00000002/art00252. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ↑ "JSTOR: Notes, Second Series, Vol. 54, No. 2, (1997 ), pp. 484-485". www.jstor.org. http://www.jstor.org/pss/899543. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ↑ Arban, Jean-Baptiste (1894, 1936, 1982). Arban's Complete Conservatory Method for TRUMPET. Carl Fischer, Inc. ISBN 0-8258-0385-3.

- ↑ Herbert L. Clarke (1984). Technical Studies for the Cornet,C. Carl Fischer, Inc. ISBN 0-8258-0158-3.

- ↑ Colin, Charles. Advanced Lip Flexibilities.

- ↑ Vassily Brandt Orchestral Etudes and Last Etudes. ISBN 0-7692-9779-X.

- ↑ "Miles Davis, Trumpeter, Dies; Jazz Genius, 65, Defined Cool". www.nytimes.com. http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0525.html. Retrieved 2008-05-03.

- ↑ "Ferguson, Maynard". Encyclopedia of Music in Canada. The Canadian Encyclopedia. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=U1ARTU0001188. Retrieved 2008-01-02.

- ↑ Keith Anderson, liner notes for Naxos CD 8.550243, Famous Trumpet Concertos, "Haydn's concerto, written for Weidinger in 1796, must have startled contemporary audiences by its novelty. At the first performance of the new concerto in Vienna in 1800 a trumpet melody was heard in a lower register than had hitherto been practicable."

Bibliography

- Don L. Smithers, The Music and History of the Baroque Trumpet Before 1721, Syracuse University Press, 1973, ISBN 0815621574

- Philip Bate, The Trumpet and Trombone: An Outline of Their History, Development, and Construction, Ernest Benn, 1978, ISBN 0393021297

- Roger Sherman, Trumpeter's Handbook: A Comprehensive Guide to Playing and Teaching the Trumpet, Accura Music, 1979, ISBN 0918194024

- Stan Skardinski, You Can't Be Timid With a Trumpet: Notes from the Orchestra, Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Books, 1980, ISBN 0688419631

- Robert Barclay, The Art of the Trumpet-Maker: The Materials, Tools and Techniques of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries in Nuremberg , Oxford University Press, 1992, ISBN 0198162235

- James Arthur Brownlow, The Last Trumpet: A History of the English Slide Trumpet, Pendragon Press, 1996, ISBN 0945193815

- Frank Gabriel Campos, Trumpet Technique, Oxford University Press, 2005, ISBN 0195166922

- Gabriele Cassone, The Trumpet Book, pages 352+CD, illustrated, Zecchini Editore, 2009, ISBN 8887203806

External links

- International Trumpet Guild international trumpet players' association with online library of scholarly journal back issues, news, jobs and other trumpet resources.

- Trumpet Playing Articles by Jeff Purtle, protege of Claude Gordon

- Jay Lichtmann's trumpet studies Scales and technical trumpet studies.

- Dallas Music — a non-profit musical instrument resource site

- A trumpet fingering chartPDF (43.2 KiB)

- Trumpet History articles essays on trumpet history and construction.

- Trumpet Exercises a wiki-based trumpet exercise database.