Transubstantiation

| Part of the series on Communion |

|

|

also known as |

|

|

Theology Real Presence |

|

|

Theologies contrasted |

|

|

Important theologians |

|

|

Related Articles |

|

In Roman Catholic theology, "transubstantiation" (in Latin, transsubstantiatio, in Greek μετουσίωσις (metousiosis)) means the change of the substance of bread and wine into the substance of the Body and Blood (respectively)[1] of Christ in the Eucharist, while all that is accessible to the senses (accidents) remains as before.[2][3]

Some Greek confessions use the term "transubstantiation" (in Greek, metousiosis), but most Orthodox Christian traditions play down the term itself, and the notions of "substance" and "accidents", while adhering to the holy mystery that bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ during Divine Liturgy. Other terms such as "trans-elementation" (μεταστοιχείωσις metastoicheiosis) and "re-ordination" (μεταρρύθμισις metarrhythmisis) are more common among the Orthodox.

The earliest known use of the term "transubstantiation" to describe the change from bread and wine to body and blood of Christ was by Hildebert de Lavardin, Archbishop of Tours (died 1133), in the eleventh century and by the end of the twelfth century the term was in widespread use.[4] In 1215, the Fourth Council of the Lateran spoke of the bread and wine as "transubstantiated" into the body and blood of Christ: "His body and blood are truly contained in the sacrament of the altar under the forms of bread and wine, the bread and wine having been transubstantiated, by God's power, into his body and blood."[5]

During the Protestant Reformation, the doctrine of transubstantiation was heavily criticised as an import into Christian teaching of Aristotelian "pseudo-philosophy,"[6] in favour of the doctrine of consubstantiation, Martin Luther's sacramental union, or in favour, per Huldrych Zwingli, of the Eucharist as memorial.[7]

The Council of Trent in its thirteenth session ending October 11, 1551, defined transubstantiation as "that wonderful and singular conversion of the whole substance of the bread into the Body, and of the whole substance of the wine into the Blood – the species only of the bread and wine remaining – which conversion indeed the Catholic Church most aptly calls Transubstantiation".[8]

This council thus officially approved use of the term "transubstantiation" to express the Catholic Church's teaching on the subject of the conversion of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist,[9] with the aim of safeguarding Christ's presence as a literal truth, while emphasizing the fact that there is no change in the empirical appearances of the bread and wine.[10] But it did not impose the Aristotelian theory of substance and accidents: it spoke only of the "species" (the appearances), not the philosophical term "accidents", and the word "substance" was in ecclesiastical use for many centuries before Aristotelian philosophy was adopted in the West,[11] as shown for instance by its use in the Nicene Creed which speaks of Christ having the same "οὐσία" (Greek) or "substantia" (Latin) as the Father.

Contents |

Roman Catholic theology of transubstantiation

"Substance" here means what something is in itself. (For more on the philosophical concept, see Substance theory.) A hat's shape is not the hat itself, nor is its colour, size, softness to the touch, nor anything else about it perceptible to the senses. The hat itself (the "substance") has the shape, the color, the size, the softness and the other appearances, but is distinct from them. While the appearances, which are referred to by the philosophical term accidents, are perceptible to the senses, the substance is not.[12]

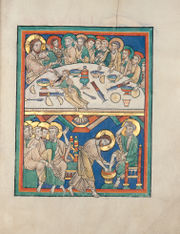

When at his Last Supper, Jesus said: "This is my body",[13] what he held in his hands still had all the appearances of bread: these "accidents" remained unchanged. However, the Roman Catholic Church believes that, when Jesus made that declaration,[14] the underlying reality (the "substance") of the bread was converted to that of his body. In other words, it actually was his body, while all the appearances open to the senses or to scientific investigation were still those of bread, exactly as before. The Catholic Church holds that the same change of the substance of the bread and of the wine occurs at the consecration of the Eucharist[15] when the words are spoken "This is my body ... this is my blood." In Orthodox confessions, the change is said to take place during the prayer of thanksgiving.

Believing that Christ is risen from the dead and is alive, the Catholic Church holds that when the bread is changed into his body, not only his body is present, but Christ as a whole is present (i.e. body and blood, soul and divinity.) The same holds for the wine changed into his blood.[16] This belief goes beyond the doctrine of transubstantiation, which directly concerns only the transformation of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ.

In accordance with this belief that Christ is really, truly and substantially present under the remaining appearances of bread and wine, and continues to be present as long as those appearances remain, the Catholic Church preserves the consecrated elements, generally in a church tabernacle, for administering Holy Communion to the sick and dying, and also for the secondary, but still highly prized, purpose of adoring Christ present in the Eucharist.

The Roman Catholic Church considers the doctrine of transubstantiation to be concerned with what is changed, and not how the change occurs; it teaches that the accidents that remain are real, not an illusion, and that Christ is "really, truly, and substantially present" in the Eucharist.[17]

In the acrimonious arguments which characterised the relationship between Roman Catholicism and Protestantism in the 16th century, the Council of Trent declared subject to the ecclesiastical penalty of anathema anyone who:

- "denieth, that, in the sacrament of the most holy Eucharist, are contained truly, really, and substantially, the body and blood together with the soul and divinity of our Lord Jesus Christ, and consequently the whole Christ; but saith that He is only therein as in a sign, or in figure, or virtue" and anyone who "saith, that, in the sacred and holy sacrament of the Eucharist, the substance of the bread and wine remains conjointly with the body and blood of our Lord Jesus Christ, and denieth that wonderful and singular conversion of the whole substance of the bread into the Body, and of the whole substance of the wine into the Blood - the species only of the bread and wine remaining - which conversion indeed the Catholic Church most aptly calls Transubstantiation."[8]

Protestant denominations have not generally subscribed to belief in transubstantiation or consubstantiation.

As already stated, the Roman Catholic Church insists that the "accidents" that remain are real. In the sacrament these are the signs of the reality that they efficaciously signify.[18] And by definition sacraments are "efficacious signs of grace, instituted by Christ and entrusted to the Catholic Church, by which divine life is dispensed to us."[19]

Scriptural interpretations

While the word "transubstantiation" is not found in the Bible, those who believe that the reality in the Eucharist is the body and blood of Christ and no longer bread and wine hold that this is implicitly taught in the New Testament.[20]

Eastern Orthodox, Oriental Orthodox, and Roman Catholics, who together constitute the majority of Christians[21] (see List of Christian denominations by number of members), hold that the consecrated elements in the Eucharist are indeed the body and blood of Christ; they also believe both a valid sacramental priesthood and the Words of Institution are necessary to make the sacrament present. Among Reform and Protestant Christian churches, some Lutherans and Anglicans hold the same belief.[22] They see as the main scriptural support for their belief that in the Eucharist the bread and wine are actually changed into the body and blood of Christ the words of Jesus himself at his Last Supper: the Synoptic Gospels[23] and Saint Paul's First Epistle to the Corinthians[24] recount that in that context Jesus said of what to all appearances were bread and wine: "This is my body … this is my blood" or, in the case of what appeared to be wine, "… this cup is the new covenant in my blood". Belief in the change of the bread and wine into the body and blood of Christ is based on these words of Christ at the Last Supper as interpreted by Christians from the earliest times, as for instance by Ignatius of Antioch, Justin Martyr, and Clement of Rome (who may have been the same Clement as mentioned in the Bible).

Other Protestants do not accept this literal interpretation of Jesus. Protestant Scripture-based arguments fall into different classes: figurative versus literal language, grammatical cues, and comparisons with other passages. The Protestant view on Communion varies, though the bread and wine are viewed only symbolically by most. While the Reformed (Calvinist and Presbyterian) denominations refer to it as a "sacrament", most Protestants consider it an "ordinance".

Jesus repeatedly spoke in non-literal terms e.g. "I am the door", "I am the vine", "Beware of the leaven of the Pharisees" (Matthew 16:6-12), etc. Figurative language in the Synoptic Gospels, the gospels that give the words of Jesus at his Last Supper, includes: "You are the salt of the earth ... You are the light of the world" (Matthew 5:13-14) and many other verses. It is accepted by Catholics and Protestants alike that Luke 22:20 and I Corinthians 11:25 are figurative where Jesus says that the cup is the new covenant.

Believers in the literal sense of Christ's words, "This is my body", "This is my blood" claim that there is a marked contrast between metaphorical figurative expressions, which of their nature have a symbolic meaning, and what Jesus said about concrete things such as the bread and wine. Catholics point to St. Paul's discourse in I Corinthians, in which he explicitly rhetorically states, "is the bread that we eat not a sharing in the Body of Christ?" and that those who profane the Eucharist are guilty of the Body and Blood of the Lord. They also point to the beliefs of the early Church, in which the writings of the early Church Fathers document a belief in the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist.

Some Protestants, however, use a grammatical argument, that because the Greek word "This" in "This is my body" is in the nominative singular neuter, it does not refer to the "bread" which is a masculine noun, but instead it means "this thing" (neuter) or refers to the "body", which is a grammatically neuter word.

Comparing Scripture with Scripture, Protestants point to Matthew 16:6-12, where Jesus spoke of "the leaven of the Pharisees and the Sadducees": the disciples thought he said it because they had brought no bread, but Jesus made them understand that he was referring to the teaching of the Pharisees and the Sadducees. This is an example where a metaphorical interpretation was allegedly intended by Christ, whereas his listeners originally understood him literally.

The Gospel of John presents Jesus as saying: "Unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood you have no life in you … he who eats my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me and I in him" (6:53-56), and as then not toning down these sayings, even when many of his disciples thereupon abandoned him (6:66), shocked at the idea. Protestants compare that passage to John 6:63 where Jesus says "the flesh profits nothing". However, Catholics argue, if this was meant to refer to Jesus' flesh, His flesh dying on the cross would profit nothing, which is theologically unacceptable to both Catholics and Protestants.

Another key Protestant contention is that Hebrews 9:11-10:18 speak of a "one-time" sacrifice, as opposed to the view of Christ's body being broken repeatedly or the blood being shed repeatedly. The response to this contention is that there is not "another sacrifice", but only a making present in different times and places of the one sacrifice of Christ: "The sacrifice of Christ and the sacrifice of the Eucharist are one single sacrifice."[25] The same, singular sacrifice is made present at Mass, in the Catholic view, it is not a new or "repeat sacrifice".

Catholics compare the idea of mere bread and wine with a passage of Scripture that implies it is something more than that. In response to a report that, when Corinthian Christians came together to celebrate the Lord's Supper, there were divisions among them, with some eating and drinking to excess, while others were hungry (1 Corinthians 11:17-22), Paul the Apostle reminded them of Jesus' words at the Last Supper (1 Corinthians 11:23-25) and concluded: "Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord" (1 Corinthians 11:27).

In general, Eastern Orthodox and Catholics consider it unnecessary to "prove" from texts of Scripture a belief that they see as held by Christians from the earliest, apostolic times. Catholics point to the fact that the Catholic Church and its teaching existed before any part of the New Testament had been assembled and canonized, and that the teaching of the Apostles was thus transmitted not only in writing but also orally and via tradition handed down to the Catholic bishops in apostolic succession.[26] Catholics further believe the Catholic Church predates the New Testament altogether, as they believe their Church to be the original Church founded by Christ. The Eastern Orthodox hold a similar view. Both Catholics and Eastern Orthodox see nothing in Scripture that contradicts the transubstantiation (versus consubstantiation) teaching that the reality beneath the visible signs in the Eucharist is the body and blood of Christ and no longer bread and wine. Instead, they see this teaching as definitely implied and even explicitly taught by both Christ and St. Paul in the Bible.

In the Messianic Jewish Passover Seder the blessing on the bread is the Grace After Meals "Birkat Hamazon", and the cup after the meal is the Cup of Blessing or Cup or Redemption. With this interpretation, the bread and wine which once pointed back to Passover, would henceforth point to Christ's body and blood being sacrificed for mankind's redemption. When Jesus said "As often as you eat this bread and drink this cup, do this in remembrance of me," he would have had a very specific occasion in mind, that being the Passover bread and the redemption cup after the Seder meal.

History

Patristic period

The belief that the Eucharist conveyed to the believer the body and blood of Christ appears to have been widespread from an early date, and the elements were commonly referred to as the body and the blood by early Christian writers. The early Christians who use these terms also speak of it as the flesh and blood of Christ, the same flesh and blood which suffered and died on the cross.

The short document known as the Teaching of the Apostles or Didache, which may be the earliest Christian document outside of the New Testament to speak of the Eucharist, says, "Let no one eat or drink of the Eucharist with you except those who have been baptized in the Name of the Lord,"[27] for it was in reference to this that the Lord said, "Do not give that which is holy to dogs." Matthew 7:6

A letter by Saint Ignatius of Antioch to the Romans, written in 106AD says: "I desire the bread of GOD, which is the flesh of Jesus Christ."[28]

Writing to the Christians of Smyrna, in about AD 106, Saint Ignatius warned them to "stand aloof from such heretics", because, among other reasons, "they abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they confess not the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ, which suffered for our sins, and which the Father, of His goodness, raised up again."[29]

In about 150, Justin Martyr wrote of the Eucharist: "Not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Savior, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh."[30]

Justin Martyr wrote, in Dialogue with Trypho, ch 70: "Now it is evident, that in this prophecy to the bread which our Christ gave us to eat, in remembrance of His being made flesh for the sake of His believers, for whom also He suffered; and to the cup which He gave us to drink, in remembrance of His own blood, with giving of thanks."

In about 200 AD, Tertullian wrote (Against Marcion IV. 40): "Taking bread and distributing it to his disciples he made it his own body by saying, 'This is my body,' that is a 'figure of my body.' On the other hand, there would not have been a figure unless there was a true body."

The Apostolic Constitutions (compiled c. 380) says: "Let the bishop give the oblation, saying, The body of Christ; and let him that receiveth say, Amen. And let the deacon take the cup; and when he gives it, say, The blood of Christ, the cup of life; and let him that drinketh say, Amen."[31]

Ambrose of Milan (d. 397) wrote:

- Perhaps you will say, "I see something else, how is it that you assert that I receive the Body of Christ?" ... Let us prove that this is not what nature made, but what the blessing consecrated, and the power of blessing is greater than that of nature, because by blessing nature itself is changed. ... For that sacrament which you receive is made what it is by the word of Christ. But if the word of Elijah had such power as to bring down fire from heaven, shall not the word of Christ have power to change the nature of the elements? ... Why do you seek the order of nature in the Body of Christ, seeing that the Lord Jesus Himself was born of a Virgin, not according to nature? It is the true Flesh of Christ which crucified and buried, this is then truly the Sacrament of His Body. The Lord Jesus Himself proclaims: "This is My Body." Before the blessing of the heavenly words another nature is spoken of, after the consecration the Body is signified. He Himself speaks of His Blood. Before the consecration it has another name, after it is called Blood. And you say, Amen, that is, It is true. Let the heart within confess what the mouth utters, let the soul feel what the voice speaks."[32]

Other fourth-century Christian writers say that in the Eucharist there occurs a "change",[33] "transelementation",[34] "transformation",[35] "transposing",[36] "alteration"[37] of the bread into the body of Christ.

In 400 AD, Augustine quotes Cyprian (200 AD): "For as Christ says 'I am the true vine,' it follows that the blood of Christ is wine, not water; and the cup cannot appear to contain His blood by which we are redeemed and quickened, if the wine be absent; for by the wine is the blood of Christ typified, ..."[38]

Middle Ages

In the eleventh century, Berengar of Tours denied that any material change in the elements was needed to explain the Eucharistic Presence, thereby provoking a considerable stir.[4] Berengar's position was never diametrically opposed to that of his critics, and he was probably never excommunicated. But the controversy that he aroused forced people to clarify the doctrine of the Eucharist.[39]

The earliest known use of the term "transubstantiation" to describe the change from bread and wine to body and blood of Christ was by Hildebert de Lavardin, Archbishop of Tours (died 1133), in about 1079,[40] long before the Latin West, under the influence especially of Thomas Aquinas (c. 1227-1274), accepted Aristotelianism.

Although it was only in the West that Aristotelian philosophy prevailed,[41] the objective reality of the Eucharistic change is also believed in by the Eastern Orthodox Church and the other ancient Churches of the East (see metousiosis).

In 1215, the Fourth Lateran Council used the word transubstantiated in its profession of faith, when speaking of the change that takes place in the Eucharist. It was only later in the thirteenth century that Aristotelian metaphysics was accepted and a philosophical elaboration in line with that metaphysics was developed, which found classic formulation in the teaching of Saint Thomas Aquinas."[4]

In 1551 the Council of Trent officially defined, with a minimum of technical philosophical language,[4] that "by the consecration of the bread and wine there takes place a change of the whole substance of the bread into the substance of the body of Christ our Lord and of the whole substance of the wine into the substance of his blood. This change the holy Catholic Church has fittingly and properly called transubstantiation."[42]

Protestant Reformation (Criticism of Transubstantiation)

In the Protestant Reformation, the doctrine of transubstantiation became a matter of much controversy. Martin Luther held that "It is not the doctrine of transubstantiation which is to be believed, but simply that Christ really is present at the Eucharist".[43] In his "On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church" (published on 6 October 1520) Luther wrote:

- Therefore it is an absurd and unheard-of juggling with words, to understand "bread" to mean "the form, or accidents of bread," and "wine" to mean "the form, or accidents of wine." Why do they not also understand all other things to mean their forms, or accidents? Even if this might be done with all other things, it would yet not be right thus to emasculate the words of God and arbitrarily to empty them of their meaning.

- Moreover, the Church had the true faith for more than twelve hundred years, during which time the holy Fathers never once mentioned this transubstantiation — certainly, a monstrous word for a monstrous idea — until the pseudo-philosophy of Aristotle became rampant in the Church these last three hundred years. During these centuries many other things have been wrongly defined, for example, that the Divine essence neither is begotten nor begets, that the soul is the substantial form of the human body, and the like assertions, which are made without reason or sense, as the Cardinal of Cambray himself admits.[44]

In his 1528 Confession Concerning Christ's Supper he wrote:

- Why then should we not much more say in the Supper, "This is my body", even though bread and body are two distinct substances, and the word "this" indicates the bread? Here, too, out of two kinds of objects a union has taken place, which I shall call a "sacramental union", because Christ's body and the bread are given to us as a sacrament. This is not a natural or personal union, as is the case with God and Christ. It is also perhaps a different union from that which the dove has with the Holy Spirit, and the flame with the angel, but it is also assuredly a sacramental union.[45]

What Luther thus called a "sacramental union" is often called consubstantiation by non-Lutherans.

In "On the Babylonian Captivity" Luther upheld belief in the Real Presence of Jesus and in his 1523 treatise The Adoration of the Sacrament defended adoration of the body and blood of Christ in the Eucharist.

Huldrych Zwingli taught that the sacrament is purely symbolic and memorial in character, arguing that this was the meaning of Jesus' instruction: "Do this in remembrance of me".[46]

The Thirty-nine articles of religion in the Church of England declare: "Transubstantiation (or the change of the substance of Bread and Wine) in the Supper of the Lord, cannot be proved by holy Writ; but is repugnant to the plain words of Scripture, overthroweth the nature of a Sacrament, and hath given occasion to many superstitions";[47] and made assistance at Mass illegal.[48]

Views of other Churches on transubstantiation

Eastern Christianity

The Eastern Catholic, Oriental Orthodox and Eastern Orthodox Churches, along with the Assyrian Church of the East, agree that in a valid Divine Liturgy bread and wine truly and actually become the body and blood of Christ. They have in general refrained from philosophical speculation, and usually rely on the status of the doctrine as a "Mystery," something known by divine revelation that could not have been arrived at by reason without revelation. Accordingly, they prefer not to elaborate upon the details and remain firmly within Holy Tradition, than to say too much and possibly deviate from the truth. However, there are official church documents that speak of a "change" (in Greek μεταβολή) or "metousiosis" (μετουσίωσις) of the bread and wine. "Μετ-ουσί-ωσις" (met-ousi-osis) is the Greek word used to represent the Latin word "trans-substanti-atio",[49][50] as Greek "μετα-μόρφ-ωσις" (meta-morph-osis) corresponds to Latin "trans-figur-atio". Examples of official documents of the Eastern Orthodox Church that use the term "μετουσίωσις" or "transubstantiation" are the Longer Catechism of The Orthodox, Catholic, Eastern Church (question 340) and the declaration by the Eastern Orthodox Synod of Jerusalem of 1672:

- "In the celebration of [the Eucharist] we believe the Lord Jesus Christ to be present. He is not present typically, nor figuratively, nor by superabundant grace, as in the other Mysteries, nor by a bare presence, as some of the Fathers have said concerning Baptism, or by impanation, so that the Divinity of the Word is united to the set forth bread of the Eucharist hypostatically, as the followers of Luther most ignorantly and wretchedly suppose. But [he is present] truly and really, so that after the consecration of the bread and of the wine, the bread is transmuted, transubstantiated, converted and transformed into the true Body Itself of the Lord, Which was born in Bethlehem of the ever-Virgin, was baptized in the Jordan, suffered, was buried, rose again, was received up, sits at the right hand of the God and Father, and is to come again in the clouds of Heaven; and the wine is converted and transubstantiated into the true Blood Itself of the Lord, Which as He hung upon the Cross, was poured out for the life of the world.[51]

Anglicanism

During the reign of King Henry VIII of England, the official teaching was identical with the Roman Catholic Church's doctrine before and after Henry's break with Rome by declaring that the Pope had no jurisdiction in England. A decade before the break the king wrote a book in defence of Catholic doctrine for which the Pope rewarded him with the title of Defender of the Faith, a title still claimed and held by English and, after 1707, British monarchs. Under Henry's son, Edward VI, the Church of England began to accept some aspects of Protestant theology and rejected transubstantiation. Elizabeth I, as part of the Elizabethan Religious Settlement, gave royal assent to the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion, which sought to distinguish Anglican from Roman Church doctrine. The Articles declared that "Transubstantiation (or the change of the substance of Bread and Wine) in the Supper of the Lord, cannot be proved by holy Writ; but is repugnant to the plain words of Scripture, overthroweth the nature of a Sacrament, and hath given occasion to many superstitions."

Anglicans generally consider no teaching binding that, according to the Articles, "cannot be found in Holy Scripture or proved thereby". Consequently, some Anglicans (especially Anglo-Catholics and High Church Anglicans) accept transubstantiation while others do not. In any case, nowadays even Church of England clergy are only required to assent that the Thirty-nine Articles have borne witness to the Christian faith.[52] In some Anglican churches other than the Church of England even this is not required. While Archbishop John Tillotson decried the "real barbarousness of this Sacrament and Rite of our Religion", considering it a great impiety to believe that people who attend Holy Communion "verily eat and drink the natural flesh and blood of Christ. And what can any man do more unworthily towards a Friend? How can he possibly use him more barbarously, than to feast upon his living flesh and blood?" (Discourse against Transubstantiation, London 1684, 35), official writings of the churches of the Anglican Communion have consistently upheld belief in the Real Presence. Some recent Anglican writers explicitly accept the doctrine of transubstantiation[53] or, while avoiding the term "transubstantiation", speak of an "objective presence" of Christ in the Eucharist. On the other hand, others hold views such as consubstantiation or "pneumatic presence", close to those of some Reformed Protestant churches.

Theological dialogue with the Roman Catholic Church has produced common documents that speak of "substantial agreement" about the doctrine of the Eucharist: the ARCIC Windsor Statement of 1971,[54] and its 1979 Elucidation.[55] Remaining arguments can be found in the Church of England's pastoral letter: The Eucharist: Sacrament of Unity.[56]

Lutheranism

Luther explicitly rejected transubstantiation, believing that the bread and wine remained fully bread and fully wine while also being fully the body and blood of Jesus Christ. Luther instead emphasized the sacramental union (not exactly the consubstantiation, as it is often claimed). Lutherans believe that within the Eucharistic celebration the body and blood of Jesus Christ are objectively present "in, with, and under the forms" of bread and wine (cf. Book of Concord). They place great stress on Jesus' instructions to "take and eat", and "take and drink", holding that this is the proper, divinely ordained use of the sacrament, and, while giving it due reverence, scrupulously avoid any actions that might indicate or lead to superstition or unworthy fear of the sacrament.

Other Protestants

Many Protestant denominations believe that the Lord's Supper is a symbolic act done in remembrance of what Christ has done for us on the cross. For example, according to the Official Creed of the Assemblies of God - an Evangelical Protestant church - Holy Communion, or "The Lord's Supper, consisting of the elements--bread and the fruit of the vine--is the symbol expressing our sharing the divine nature of our Lord Jesus Christ (2 Peter 1:4); a memorial of His suffering and death, and a prophecy of His suffering and death (1 Corinthians 11:26); and is enjoined on all believers "till He come!"[57] He commanded the apostles: "This do in remembrance of me", after "he took bread, and gave thanks, and broke it, and gave unto them, saying, This is my body which is given for you" (Luke 22:19, 1 Corinthians 11:24). Therefore they see it as a symbolic act done in remembrance and as a declaration (1 Corinthians 11:26) of faith in what they consider Christ's finished (John 19:30) work on the cross. They see the historical Last Supper as being not a literal event as Catholics do where Jesus; that is, Jesus humanly present in flesh and blood simultaneously shared out his sacramental Body and Blood under the appearances of bread and wine to his disciples, but as a prophetic act: in stating "This is my body", "This is the cup of my blood", Jesus was giving a figure of the sacrifice he would make upon the Cross the following day. Other Protestants also reject the idea that a priest, acting, he believes, in the name of Christ, not in his own name, can transform bread and wine into the actual body and blood of God incarnate in Jesus Christ, and many of them see the doctrine as a problem because of its connection with practices such as Eucharistic adoration, which they believe may be idolatry.[58] They base their criticism of the doctrine of transubstantiation (and also of the Real Presence) on a number of verses of the Bible, including Exodus 20:4-5, and on their interpretation of the central message of the Gospel. Scripture does not explicitly say "the bread was transformed" or "changed" in any way, and therefore they consider the doctrine of transubstantiation to be unbiblical from more than one approach. As already stated above, they also object to using early Christian writings to support belief that the bread of the Lord's Supper is more than a metaphor for Christ's body, because such writings are not Scripture nor writings that were able to be verified by any prophet or apostle, especially when they believe such doctrines contradict inspired Scripture.

A few Protestants apply to the doctrine of the Real Presence the warning that Jesus gave to His disciples in Matthew 24:26: "Wherefore if they shall say unto you, Behold, he is in the desert; go not forth: behold, he is in the secret chambers; believe it not", believing that "secret chambers" (also translated as "inner rooms", "a secret place", "indoors in the room") fits as a description for church tabernacles in which consecrated hosts are stored. They thus do not believe the words of those who say that Jesus Christ's person, spirit and divinity reside inside church tabernacles in host form. They believe that Christ's words at the Last Supper were meant to be taken metaphorically and believe that support for a metaphorical interpretation comes from Christ's other teachings that utilized food in general (John 4:32-34), bread (John 6:35), and leaven (Matthew 16:6-12), as metaphors. They believe that when Christ returns in any substance with any physical form (accidental or actual), it will be apparent to all and that no man will have to point and say "there He is".

Protestant denominations, such as Methodists and some Presbyterians, profess belief in the Real Presence, but offer explanations other than transubstantiation. Classical Presbyterianism held the Calvinist view of "pneumatic" presence or "spiritual feeding." However, when the Presbyterian Church (USA) signed "A Formula for Agreement" with the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, both affirmed belief in the Real Presence. John Calvin "can be regarded as occupying a position roughly midway between" (McGrath) the doctrines developed by Martin Luther on the one hand and Huldrych Zwingli, on the other: "Believers ought always to live by this rule: whenever they see symbols appointed by the Lord, to think and be convinced that the truth of the thing signified is surely present there. For why should the Lord put in your hand the symbol of his body, unless it was to assure you that you really participate in it? And if it is true that a visible sign is given to us to seal the gift of an invisible thing, when we have received the symbol of the body, let us rest assured that the body itself is also given to us." (Calvin); that is, "the thing that is signified is effected by its sign" (McGrath).[59]

Churches that hold strong beliefs against the consumption of alcohol replace wine with grape juice during the Lord's Supper. Other groups, such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, began the use of bread and water in the late 1800s to symbolize Christ's body and blood. Prior to this they typically used wine and operated a number of vineyards for this purpose.

See also

- Consubstantiation

- Host desecration

- New Covenant

- Transignification

References

- ↑ According to Catholic theology, the body of the living Christ, into which the bread is changed, is necessarily accompanied by his blood, his soul and his divinity, and similarly his body, his soul and his divinity are present "by concomitance" where is blood is.

- ↑ "The conversion of the whole substance of the bread and wine into the whole substance of the Body and Blood of Christ, only the accidents (i.e. the appearances of the bread and wine) remaining" (Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church - Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280-290-3 - article Transubstantiation

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article Transubstantiation

- ↑ of Faith Fourth Lateran Council: 1215, 1. Confession of Faith, retrieved 2010-03-13.

- ↑ Luther, M. The Babylonian Captivity of the Christian Church. 1520. Quoted in, McGrath, A. 1998. Historical Theology, An Introduction to the History of Christian Thought. Blackwell Publishers: Oxford. p. 198.

- ↑ McGrath, op.cit. pp. 198-99

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Council of Trent, The Thirteenth Session

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th ed. (1911), vol 27, page 186

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica: article transubstantiation

- ↑ Charles Davis: The Theology of Transubstantiation in Sophia, Vol. 3, No. 1 / April 1964

- ↑ "The word 'substance' as here used is not a technical philosophical term, such as might be found in the philosophy of Aristotle. It was used in the early Middle Ages long before the works of Aristotle were current. 'Substance' in common-sense usage denotes the basic reality of the thing, i.e., what it is in itself. Derived from the Latin root 'sub-stare', it means what stands under the appearances, which can shift from one moment to the next while leaving the subject intact. Appearances can be deceptive. You might fail to recognize me when I put on a disguise or when I become seriously ill, but I do not cease to be the person that I was; my substance is unchanged. There is nothing obscure, then, about the meaning of 'substance' in this context" (Avery Dulles: Christ's Presence in the Eucharist: True, Real and Substantial).

- ↑ Matthew 26:26, Mark 14:22, Luke 22:18, 1 Corinthians 11:24

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1376

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1377; Christ's Presence in the Eucharist: True, Real and Substantial

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1413

- ↑ CCC 1374

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1333-1336 is headed "The signs of bread and wine".

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1131

- ↑ They see the situation as similar to that of the doctrine of the Trinity, which, though "neither the word Trinity nor the explicit doctrine appears in the New Testament, nor did Jesus and his followers intend to contradict the Shema in the Old Testament: 'Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God is one Lord' (Deuteronomy 6:4) ... is accepted in all of the historic confessions of Christianity" (Encyclopedia Britannica Online: Trinity)

- ↑ Major Branches of Religions Ranked by Number of Adherents

- ↑ Transubstantiation and the Black Rubric; and see Anglican Eucharistic theology

- ↑ Mark 14:22-24; Matthew 26:26-28; Luke 22:19-20

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 11:23-25

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, 1367

- ↑ See, for instance, The Dogmatic Tradition of the Orthodox Church, Catechism of the Catholic Church, 74-82.

- ↑ "The Didache", 9:1

- ↑ "Epistle to the Romans", 7

- ↑ Epistle to the Smyrnaeans, 7

- ↑ First Apology, LXVI

- ↑ Book VIII, section II, XIII

- ↑ On the Mysteries, 50-54

- ↑ Cyril of Jerusalem, Cat. Myst., 5, 7 (Patrologia Graeca 33:1113): μεταβολή

- ↑ Gregory of Nyssa, Oratio catechetica magna, 37 (PG 45:93): μεταστοιχειώσας

- ↑ John Chrysostom, Homily 1 on the betrayal of Judas, 6 (PG 49:380): μεταρρύθμησις

- ↑ Cyril of Alexandria, On Luke, 22, 19 (PG 72:911): μετίτησις

- ↑ John Damascene, On the orthodox faith, book 4, chapter 13 (PG 49:380): μεταποίησις

- ↑ Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, book 4, ch 21, quoting Cyprian.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3), article Berengar of Tours

- ↑ Sermones xciii; PL CLXXI, 776

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press 2005), article Aristotle

- ↑ Session XIII, chapter IV; cf. canon II)

- ↑ McGrath, op.cit., p197.

- ↑ A Prelude by Martin Luther on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, 2:26 & 2:27

- ↑ Weimar Ausgabe 26, 442; Luther's Works 37, 299-300.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 11:23-26

- ↑ Thirty-Nine Articles, article 28

- ↑ The Literature of Persecution and Intolerance; James MacCaffrey, vol. 2; St. Margaret Clitherow

- ↑ The Synod of Jerusalem and the Confession of Dositheus, A.D. 1672

- ↑ "The Holy Orthodox Church at the Synod of Jerusalem (date 1643 A.D.) used the word metousiosis--a change of ousia--to translate the Latin Transubstantiatio" (Transubstantiation and the Black Rubric).

- ↑ Confession of Dositheus (emphasis added) The Greek text is quoted in an online extract from the 1915 book "Μελέται περί των Θείων Μυστηρίων" (Studies on the Divine Mysteries/Sacraments) by Saint Nektarios.

- ↑ The Declaration of Assent

- ↑ Transubstantiation and the Black Rubric by the Catholic Propaganda Society within the Church of England

- ↑ Pro Unione Web Site - Full Text ARCIC Eucharist

- ↑ Pro Unione Web Site - Full Text ARCIC Elucidation Eucharist

- ↑ Eucharist 2

- ↑ Official Creed of Assemblies of God

- ↑ According to Boswell's Life of Johnson, Samuel Johnson responded to such views: "Sir, there is no idolatry in the Mass. They believe GOD to be there, and they adore him."

- ↑ McGrath, op.cit., p.199.

External links

- "Transubstantiation" in Catholic Encyclopedia

- Pope Paul VI: Encyclical Mysterium Fidei

- Pope Paul VI: Credo of the People of God

- Eastern Orthodox Church statements on transubstantiation/metousiosis

- The Antiquity of the Doctrine of Transubstantiation

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||