Tramadol

-_&_(1S,2S)-Tramadol_Enantiomers_Structural_Formulae.png) |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| (1R,2R)-rel-2-[(dimethylamino)methyl]- 1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | 27203-92-5 |

| ATC code | N02AX02 |

| PubChem | CID 33741 |

| DrugBank | APRD00028 |

| ChemSpider | 31105 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C16H25NO2 |

| Mol. mass | 263.4 g/mol |

| SMILES | eMolecules & PubChem |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 68–72%(Increases with repeat dosing.) |

| Protein binding | 20% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic demethylation and glucuronidation |

| Half-life | 5–7 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. | C(AU) C(US) |

| Legal status | Prescription Only (S4) (AU) POM (UK) ℞-only (US) ℞ Prescription only |

| Routes | oral, IV, IM, rectal, sublingual, buccal, intranasal |

| |

|

Tramadol (Ultram, Tramal, others below) is a centrally-acting analgesic, used in treating moderate to moderately severe pain. The drug has a wide range of applications, including treatment for restless leg syndrome, acid reflux, and fibromyalgia. It was developed by the pharmaceutical company Grünenthal GmbH in the late 1970s.[1][2]

Tramadol possesses weak agonist actions at the μ-opioid receptor, releases serotonin, and inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine.[3][4][5][6][7][8][9]

Tramadol is a synthetic analog of the phenanthrene alkaloid codeine and, as such, is an opioid and also a prodrug (codeine is metabolized to morphine, tramadol is converted to M-1 aka O-desmethyltramadol). Opioids are chemical compounds which act upon one or more of the human opiate receptors. The euphoria and respiratory depression are mainly caused by the μ1 and μ2 receptors; the addictive nature of the drug is due to these effects as well as its serotonergic/noradrenergic effects. The opioid agonistic effect of tramadol and its major metabolite(s) are almost exclusively mediated by the substance's action at the μ-opioid receptor. This characteristic distinguishes tramadol from many other substances (including morphine) of the opioid drug class, which generally do not possess tramadol's degree of subtype selectivity.

Contents |

Uses

Tramadol is used similarly to codeine, to treat moderate to moderately severe pain and most types of neuralgia, including trigeminal neuralgia.[10] Tramadol is somewhat pharmacologically similar to levorphanol (albeit with much lower μ-agonism), as both opioids are also NMDA-antagonists which also have SNRI activity (other such opioids to do the same are dextropropoxyphene (Darvon) & M1-like molecule tapentadol (Nucynta, a new synthetic atypical opioid made to mimic the agonistic properties of tramadol's metabolite, M1(O-Desmethyltramadol). It has been suggested that tramadol could be effective for alleviating symptoms of depression, anxiety, and phobias[11] because of its action on the noradrenergic and serotonergic systems, such as its "atypical" opioid activity.[12] However, health professionals have not endorsed its use for these disorders,[13][14] claiming it may be used as a unique treatment (only when other treatments failed), and must be used under the control of a psychiatrist.[15][16]

In May 2009, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued a Warning Letter to Johnson & Johnson, alleging that a promotional website commissioned by the manufacturer had "overstated the efficacy" of the drug, and "minimized the serious risks".[17] The company which produced it, the German pharmaceutical company Grünenthal GmbH, were the ones alleged to be guilty of "minimizing" the addictive nature and proposed efficacy of the drug, although it showed little abuse liability in preliminary tests. The 2010 Physicians Desk Reference contains several warnings from the manufacturer, which were not present in prior years. The warnings include more compelling language regarding the addictive potential of tramadol, the possibility of difficulty breathing while on the medication, a new list of more serious side effects, and a notice that tramadol is not to be used in place of opiate medications for addicts. Tramadol is also not to be used in efforts to wean addict patients from opiate drugs, nor to be used to manage long-term opiate addiction.

Availability and Usage

Tramadol is usually marketed as the hydrochloride salt (tramadol hydrochloride); the tartrate is seen on rare occasions, and rarely (in the US at least) tramadol is available for both injection (intravenous and/or intramuscular) and oral administration. The most well known dosing unit is the 50 mg generic tablet made by several manufacturers. It is also commonly available in conjunction with APAP (Paracetamol, Acetaminophen) as Ultracet, in the form of a smaller dose of 37.5 mg tramadol and 325 mg of APAP. The solutions suitable for injection are used in patient-controlled analgesia pumps under some circumstances, either as the sole agent or along with another agent such as morphine.

Tramadol comes in many forms, including:

- capsules (regular and extended release)

- tablets (regular, extended release, chewable, low-residue and/or uncoated tablets that can be taken by the sublingual and buccal routes)

- suppositories

- effervescent tablets and powders

- ampules of sterile solution for SC, IM, and IV injection

- preservative-free solutions for injection by the various spinal routes (epidural, intrathecal, caudal, and others)

- powders for compounding

- liquids both with and without alcohol for oral and sub-lingual administration, available in regular phials and bottles, dropper bottles, bottles with a pump similar to those used with liquid soap and phials with droppers built into the cap

- tablets and capsules containing (acetaminophen/APAP), aspirin and other agents.

Tramadol has been experimentally used in the form of an ingredient in multi-agent topical gels, creams, and solutions for nerve pain, rectal foam, concentrated retention enema, and a skin plaster (transdermal patch) quite similar to those used with lidocaine.

Tramadol has a characteristic and unpleasant taste which is mildly bitter but much less so than morphine and codeine. Oral and sublingual drops and liquid preparations come with and without added flavoring. Its relative effectiveness via transmucosal routes (i.e. sublingual, buccal, rectal) is similar to that of codeine, and, like codeine, it is also metabolized in the liver to stronger metabolites (see below).

The maximum dosage for tramadol in any form is 400 mg per day. Certain manufacturers or formulations have lower maximum doses. For example, Ultracet (37.5 mg/325 mg tramadol/APAP tablets) is capped at 8 tablets per day (300 mg/day). Ultram ER is available in 100, 200, and 300 mg/day doses and is explicitly capped at 300 mg/day as well.

Patients taking SSRIs (Prozac, Zoloft, etc.), SNRIs (Efexor, etc.), TCAs, MAOIs, or other strong opioids (oxycodone, methadone, fentanyl, morphine), as well as the elderly (> 75 years old), pediatric (< 18 years old), and those with severely reduced renal (kidney) or hepatic (liver) function should consult their doctor regarding adjusted dosing or whether to use Tramadol at all.

Off-label and investigational uses

- diabetic neuropathy[18][19]

- postherpetic neuralgia[20][21]

- fibromyalgia[22]

- restless legs syndrome[23]

- opiate withdrawal management[24][25] /Anti-Depressant withdrawal aid (proven to be effective, especially with withdrawal from its distant relative Venlafaxine(Effexor).

- migraine headache[26]

- obsessive-compulsive disorder[27]

- premature ejaculation[28]

Veterinary

Tramadol may be used to treat post-operative, injury-related, and chronic (e.g., cancer-related) pain in dogs and cats[29] as well as rabbits, coatis, many small mammals including rats and flying squirrels, guinea pigs, ferrets, and raccoons. Tramadol comes in ampules in addition to the tablets, capsules, powder for reconstitution, and oral syrups and liquids; the fact that its characteristic taste is distasteful to dogs, but can be masked in food, makes for a means of administration. No data that would lead to a definitive determination of the efficacy and safety of tramadol in reptiles or amphibians is available at this time, and, following the pattern of all other drugs, it appears that tramadol can be used to relieve pain in marsupials such as North American opossums, Short-Tailed Opossums, sugar gliders, wallabies, and kangaroos among others.

Tramadol for animals is one of the most reliable and useful active principles available to veterinarians for treating animals in pain. It has a dual mode of action: mu agonism and mono-amine reuptake inhibition, which produces mild anti-anxiety results. Tramadol may be utilized for relieving pain in cats and dogs. This is an advantage because the use of some non-steroidal anti-inflammatory substances in these animals may be dangerous.

When animals are administered tramadol, adverse reactions can occur. The most common are constipation, upset stomach, decreased heart rate. In case of overdose, mental alteration, pinpoint pupils and seizures may appear. In such case, veterinarians should evaluate the correct treatment for these events. Some contraindications have been noted in treated animals taking certain other drugs. Tramadol should not be co-administered with selegiline or any other psychoactive class of medication such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, or monoamine oxidase inhibitors. In animals, tramadol is removed from the body via liver and kidney excretion. Animals suffering from diseases in these systems should be monitored by a veterinarian, as it may be necessary to adjust the dose.

Dosage and administration of tramadol for animals: in dogs for sufficient analgesia: 1–4 mg/kg PO q8-12h (Hardie, Lascelles et al. 2003) and to control chronic pain in cats: 4 mg/kg PO twice daily (Note: Dose extrapolated from human medicine. Tramadol has not been evaluated for toxicity in cats and has not been used extensively, but early results encouraging) (Lascelles, Robertson et al. 2003).

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

Tramadol is in FDA pregnancy category C; animal studies have shown its use to be dangerous during pregnancy and human studies are lacking. Therefore, the drug should not be taken by women that are pregnant unless "the potential benefits outweigh the risks".[30]

Tramadol causes serious or fatal side-effects in a newborn[31] including neonatal withdrawal, if the mother uses the medication during pregnancy or labor. Use of tramadol by nursing mothers is not recommended by the manufacturer because the drug passes into breast milk.[30] However, the absolute dose excreted in milk is quite low, and tramadol is generally considered to be acceptable for use in breastfeeding mothers when absolutely necessary.[32]

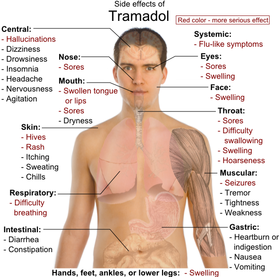

Adverse effects and drug interactions

The most commonly reported adverse drug reactions are nausea, vomiting, sweating and constipation. Drowsiness is reported, although it is less of an issue than for non-synthetic opioids. Patients prescribed tramadol for general pain relief with or without other agents have reported withdrawal symptoms including uncontrollable nervous tremors, muscle contracture, and 'thrashing' in bed (similar to restless leg syndrome) if weaning off the medication happens too quickly. Anxiety, 'buzzing', 'electrical shock' and other sensations may also be present, similar to those noted in Effexor withdrawal. Anecdotally, tramadol is widely regarded by chronic pain sufferers as being among the most difficult of the pain medications to stop after prolonged administration, as withdrawal from both the serotonergic/noradrenergic and the mu-opioid effects is present. Respiratory depression, a common side-effect of most opioids, is not clinically significant in normal doses. By itself, it can decrease the seizure threshold. When combined with SSRIs, tricyclic antidepressants, or in patients with epilepsy, the seizure threshold is further decreased. Seizures have been reported in humans receiving excessive single oral doses (700 mg) or large intravenous doses (300 mg). However, there have been several rare cases of people having grand-mal seizures at doses as low as 100–400 mg orally.[34][35][36] An Australian study found that of 97 confirmed new-onset seizures, eight were associated with tramadol, and that in the authors' First Seizure Clinic, "tramadol is the most frequently suspected cause of provoked seizures" (Labate 2005). There appears to be growing evidence that Tramadol use may have serious risks in some individuals. Seizures caused by tramadol are most often tonic-clonic seizures, more commonly known in the past as grand mal seizures. Also when taken with SSRIs, there is an increased risk of serotonin toxicity, which can be fatal. Fewer than 1% of users have a presumed incident seizure claim after their first tramadol prescription. Risk of seizure claim increases 2- to 6-fold among users adjusted for selected comorbidities and concomitant drugs. Risk of seizure is highest among those aged 25–54 years, those with more than four tramadol prescriptions, and those with a history of alcohol abuse, stroke, or head injury.[37] Dosages of warfarin may need to be reduced for anticoagulated patients to avoid bleeding complications. Constipation can be severe especially in the elderly requiring manual evacuation of the bowel. Furthermore, there are suggestions that chronic opioid administration may induce a state of immune tolerance,[38] although tramadol, in contrast to typical opioids may enhance immune function.[39][40][41] Some have also stressed the negative effects of opioids on cognitive functioning and personality.[42]

| Effect | Probability (%) |

|---|---|

| Any adverse effect | 71 |

| Drowsiness | 17 |

| Nausea | 17 |

| Dizziness | 15 |

| Constipation | 11 |

| Headache | 11 |

| Vomiting | 7 |

| Diarrhea | 6 |

| Dry Mouth | 5 |

| Fatigue | 5 |

| Indigestion | 5 |

| Seizure[37] | <1 |

Chemistry

Characteristics

Structurally, tramadol closely resembles a stripped down version of codeine. Both codeine and tramadol share the 3-methyl ether group, and both compounds are metabolized along the same hepatic pathway and mechanism to the stronger opioid, phenol agonist analogs. For codeine, this is morphine, and for tramadol, it is the M1 metabolite, O-desmethyltramadol. The closest chemical relative of tramadol in clinical use is venlafaxine (Effexor), an SSNRI. The two molecules are nearly identical. Both tramadol and venlafaxine share SSNRI properties, while venlafaxine is devoid of any opioid effects.

Structurally, tapentadol is the closest chemical relative of tramadol in clinical use. Tapentadol is also an opioid, but unlike both tramadol and venlafaxine, tapentadol represents only one stereoisomer and is the weaker of the two, in terms of opioid effect. Both tramadol and venlafaxine are racemic mixtures. Structurally, tapentadol also differs from tramadol in being a phenol, and not an ether. Also, both tramadol and venlafaxine incorporate a cyclohexyl moiety, attached directly to the aromatic, while tapentadol lacks this feature. In reality, the closest structural chemical entity to tapentadol in clinical use is the over-the-counter drug phenylephrine. Both share a meta phenol, attached to a straight chain hydrocarbon. In both cases, the hydrocarbon terminates in an amine.

Synthesis and stereoisomerism

-Tramadol.svg.png)

-Tramadol_gespiegelt.svg.png)

(1R,2R)-Tramadol (1S,2S)-Tramadol

-Tramadol.svg.png)

-Tramadol_gespiegelt.svg.png)

(1R,2S)-Tramadol (1S,2R)-Tramadol

The chemical synthesis of tramadol is described in the literature.[44] Tramadol [2-(dimethylaminomethyl)-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol] has two stereogenic centers at the cyclohexane ring. Thus, 2-(dimethylaminomethyl)-1-(3-methoxyphenyl)cyclohexanol may exist in four different configurational forms:

- (1R,2R)-isomer

- (1S,2S)-isomer

- (1R,2S)-isomer

- (1S,2R)-isomer

The synthetic pathway leads to the racemate (1:1 mixture) of (1R,2R)-isomer and the (1S,2S)-isomer as the main products. Minor amounts of the racemic mixture of the (1R,2S)-isomer and the (1S,2R)-isomer are formed as well. The isolation of the (1R,2R)-isomer and the (1S,2S)-isomer from the diastereomeric minor racemate [(1R,2S)-isomer and (1S,2R)-isomer] is realized by the recrystallization of the hydrochlorides. The drug tramadol is a racemate of the hydrochlorides of the (1R,2R)-(+)- and the (1S,2S)-(–)-enantiomers. The resolution of the racemate [(1R,2R)-(+)-isomer / (1S,2S)-(–)-isomer] was described[45] employing (R)-(–)- or (S)-(+)-mandelic acid. This process does not find industrial application, since tramadol is used as a racemate, besides known different physiological effects [46] of the (1R,2R)- and (1S,2S)-isomers.

Metabolism

Tramadol undergoes hepatic metabolism via the cytochrome P450 isozyme CYP2B6, CYP2D6 and CYP3A4, being O- and N-demethylated to five different metabolites. Of these, M1 (O-Desmethyltramadol) is the most significant since it has 200 times the μ-affinity of (+)-tramadol, and furthermore has an elimination half-life of nine hours, compared with six hours for tramadol itself. In the 6% of the population that have slow CYP2D6 activity, there is therefore a slightly reduced analgesic effect. Phase II hepatic metabolism renders the metabolites water-soluble, which are excreted by the kidneys. Thus, reduced doses may be used in renal and hepatic impairment.[47]

Mechanism of action

Tramadol acts as a μ-opioid receptor agonist,[48][49] serotonin releasing agent,[6][7][8][9] norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor,[49] NMDA receptor antagonist,[50] 5-HT2C receptor antagonist,[51] (α7)5 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist,[52] and M1 and M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist.[53][54]

The analgesic action of tramadol has yet to be fully understood, but it is believed to work through modulation of serotonin and norepinephrine in addition to its mild agonism of the μ-opioid receptor. The contribution of non-opioid activity is demonstrated by the fact that the analgesic effect of tramadol is not fully antagonised by the μ-opioid receptor antagonist naloxone.

Tramadol is marketed as a racemic mixture of the (1R,2R)- and (1S,2S)-enantiomers with a weak affinity for the μ-opioid receptor (approximately 1/6000th that of morphine; Gutstein & Akil, 2006). The (1R,2R)-(+)-enantiomer is approximately four times more potent than the (1S,2S)-(–)-enantiomer in terms of μ-opioid receptor affinity and 5-HT reuptake, whereas the (1S,2S)-(–)-enantiomer is responsible for noradrenaline reuptake effects (Shipton, 2000). These actions appear to produce a synergistic analgesic effect, with (1R,2R)-(+)-tramadol exhibiting 10-fold higher analgesic activity than (1S,2S)-(–)-tramadol (Goeringer et al., 1997).

The serotonergic-modulating properties of tramadol give tramadol the potential to interact with other serotonergic agents. There is an increased risk of serotonin toxicity when tramadol is taken in combination with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (e.g., SSRIs) or with use of a light box, since these agents not only potentiate the effect of 5-HT but also inhibit tramadol metabolism. Tramadol is also thought to have some NMDA antagonistic effects, which has given it a potential application in neuropathic pain states.

Tramadol has inhibitory actions on the 5-HT2C receptor. Antagonism of 5-HT2C could be partially responsible for tramadol's reducing effect on depressive and obsessive-compulsive symptoms in patients with pain and co-morbid neurological illnesses.[55] 5-HT2C blockade may also account for its lowering of the seizure threshold, as 5-HT2C knockout mice display significantly increased vulnerability to epileptic seizures, sometimes resulting in spontaneous death. However, the reduction of seizure threshold could be attributed to tramadol's putative inhibition of GABA-A receptors at high doses.[50]

The overall analgesic profile of tramadol supports intermediate pain especially chronic states, is slightly less effective for acute pain than hydrocodone, but more effective than codeine. It has a dosage ceiling similar to codeine, a risk of seizures when overdosed, and a relatively long half-life making its potential for abuse relatively low amongst intermediate strength analgesics.

Tramadol's primary active metabolite, O-desmethyltramadol, is a considerably more potent μ-opioid receptor agonist than tramadol itself, and is so much more so that tramadol can partially be thought of as a prodrug to O-desmethyltramadol. Similarly to tramadol, O-desmethyltramadol has also been shown be a norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, 5-HT2C receptor antagonist, and M1 and M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor antagonist.

Abuse and dependency

Physical dependence and withdrawal

Tramadol is associated with the development of physical dependence and a severe withdrawal in animals.[56] Tramadol causes typical opiate-like withdrawal symptoms as well as atypical withdrawal symptoms including seizures. The atypical withdrawal symptoms are probably related to tramadol's effect on serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake. Symptoms may include those of SSRI discontinuation syndrome, such as anxiety, depression, anguish, severe mood swings, aggressiveness, brain "zaps", electric-shock-like sensations throughout the body, paresthesias, sweating, palpitations, restless legs syndrome, sneezing, insomnia, tremors, and headache among others. In most cases, tramadol withdrawal will set in 12–20 hours after the last dose, but this can vary. Tramadol withdrawal lasts longer than that of other opioids; seven days or more of acute withdrawal symptoms can occur as opposed to typically three or four days for other codeine analogues. It is recommended that patients physically dependent on pain killers take their medication regularly to prevent onset of withdrawal symptoms and this is particularly relevant to tramadol because of its SSRI and SNRI properties, and, when the time comes to discontinue their tramadol, to do so gradually over a period of time that will vary according to the individual patient and dose and length of time on the drug.[57][58][59][60]

Psychological dependence and drug misuse

Some controversy regarding the abuse potential of tramadol exists. Grünenthal has promoted it as an opioid with a lower risk of opioid dependence than that of traditional opioids, claiming little evidence of such dependence in clinical trials (which is true, Grünenthal never claimed it to be non-addictive). They offer the theory that, since the M1 metabolite is the principal agonist at μ-opioid receptors, the delayed agonist activity reduces abuse liability. The norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor effects may also play a role in reducing dependence.

It is apparent in community practice that dependence to this agent may occur after as little as three months of use at the maximum dose—generally depicted at 400 mg per day. However, this dependence liability is considered relatively low by health authorities, such that tramadol is classified as a Schedule 4 Prescription Only Medicine in Australia, and been rescheduled in Sweden rather than as a Schedule 8 Controlled Drug like opioids.[61] Similarly, tramadol is not currently scheduled by the U.S. DEA, unlike opioid analgesics. It is, however, scheduled in certain states.[62] Nevertheless, the prescribing information for Ultram warns that tramadol "may induce psychological and physical dependence of the morphine-type".

However, due to the possibility of convulsions at high doses for some users, recreational use can be very dangerous.[63] Tramadol can, however, via agonism of μ opioid receptors, produce effects similar to those of other opioids (Codeine and other weak opiods), although not nearly as intense due to tramadol's much lower affinity for this receptor. Tramadol can cause a higher incidence of nausea, dizziness, loss of appetite compared with opiates which could deter abuse to some extent.[64] Tramadol can help alleviate withdrawal symptoms from opiates, and it is much easier to lower the quantity of its usage, compared with opioids such as hydrocodone and oxycodone.[65] It may also have large effect on sleeping patterns and high doses may cause insomnia.

- (Especially for those on methadone, both for maintenance and recreation. Though there is no scientific proof tramadol lessens effects or is a mixed agonist-antagonist, some people get the impression it is, while someone else might benefit being prescribed both for pain and B/T pain)[66]

Detection in biological fluids

Tramadol and O-desmethyltramadol may be quantitated in blood, plasma or serum to monitor for abuse, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or assist in the forensic investigation of a traffic or other criminal violation or a sudden death. Most commercial opiate immunoassay screening tests do not cross-react significantly with tramadol or its major metabolites, so chromatographic techniques must be used to detect and quantitate these substances. The concentrations of O-desmethyltramadol in the blood or plasma of a person who has taken tramadol are generally 10-20% those of the parent drug.[67][68][69]

Legal status

Tramadol is a controlled substance in some US states and Canada, and requires a prescription. However, Tramadol is readily available by remote prescription including via internet pharmacies with relative ease. As of December 5, 2008, Kentucky has classified tramadol as a Schedule IV controlled substance.[62] The Military Pain Care Act of 2008 requires on base pharmacies to label tramadol as a controlled substance[70]

Tramadol is available over the counter without prescription in a few countries.[71] Sweden, as of May 2008, has chosen to classify tramadol as a controlled substance in the same way as codeine and dextropropoxyphene. This means that the substance is a scheduled drug. But unlike codeine and dextropropoxyphene, a normal prescription can be used at this time.[72] In Mexico, combined with paracetamol and sold under the brand name Tramacet, it is widely available without a prescription. In most Asian countries such as the Philippines, it is sold as a capsule under the brand name Tramal, where it is mostly used to treat labor pains.

Tramadol (as the racemic, cis-hydrochloride salt), is available as a generic in the U.S. from any number of different manufacturers, including Caraco, Mylan, Cor Pharma, Mallinckrodt, Pur-Pak, APO, Teva, and many more. Typically, the generic tablets are sold in 50 mg tablets. Brand name formulations include Ultram ER, and the original Ultram from Ortho-McNeil (cross-licensed from Grünenthal GmbH). The extended-release formulation of tramadol—which, amongst other factors—was intended to be more abuse-deterrent than the instant release) allegedly possesses more abuse liability than the instant release formulation. Through a confluence of pharmacodynamics, large doses of instant release tramadol is likely to cause tachycardia and extreme panic, as the acute SNRI effects predominate. The more desirable opioid effects (which are due mainly to the M1 metabolite, after first-pass hepatic metabolism), are more pronounced with the extended-release (ER) formulation, as tramadol is not absorbed all at once. Thus, the acute (undesirable) SNRI effects are largely avoided, while the longer term, more desirable opioid effects, are enhanced. Another way to get a similar overall effect, would be to take a small dose of tramadol every half hour, being very careful to watch total intake as tramadol can be a very dangerous drug in overdose. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tramadol in March 1995 and an extended-release (ER) formulation in September 2005.[73] It is covered by U.S. patents nos. 6,254,887[74] and 7,074,430.[75][76] The FDA lists the patents as scheduled for expiration on May 10, 2014.[75] However, in August 2009, U.S. District Court for the District of Delaware ruled the patents invalid, which, if it survives appeal, would permit manufacture and distribution of generic equivalents of Ultram ER in the United States.[77]

Proprietary preparations

Grünenthal GmbH, which still owns the patent on tramadol, has cross-licensed the drug to pharmaceutical companies internationally. Thus, tramadol is marketed under many trade names around the world, including:

|

|

|

|

See also

- Bromadol

- C-8813

- Ciramadol

- Faxeladol

- Profadol

- Tapentadol

References

- ↑ US patent 3652589, Flick, Kurt; Frankus, Ernst, "1-(m-Substituted Phenyl)-2-Aminomethyl Cyclohexanols", issued 28 March 1972

- ↑ Tramal, What is Tramal? About its Science, Chemistry and Structure

- ↑ Dayer, P; Desmeules, J; Collart, L (1997). "Pharmacology of tramadol". Drugs 53 Suppl 2: 18–24. doi:10.2165/00003495-199700532-00006. PMID 9190321.

- ↑ Lewis, KS; Han, NH (1997). "Tramadol: a new centrally acting analgesic". American journal of health-system pharmacy 54 (6): 643–52. PMID 9075493.

- ↑ WO patent 2007070779, Singh, Chandra, "A Method to Treat Premature Ejaculation in Humans", issued 21 June 2007

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Driessen B, Reimann W (January 1992). "Interaction of the central analgesic, tramadol, with the uptake and release of 5-hydroxytryptamine in the rat brain in vitro". British Journal of Pharmacology 105 (1): 147–51. PMID 1596676.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Bamigbade TA, Davidson C, Langford RM, Stamford JA (September 1997). "Actions of tramadol, its enantiomers and principal metabolite, O-desmethyltramadol, on serotonin (5-HT) efflux and uptake in the rat dorsal raphe nucleus". British Journal of Anaesthesia 79 (3): 352–6. PMID 9389855. http://bja.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9389855.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Reimann W, Schneider F (May 1998). "Induction of 5-hydroxytryptamine release by tramadol, fenfluramine and reserpine". European Journal of Pharmacology 349 (2-3): 199–203. doi:10.1016/S0014-2999(98)00195-2. PMID 9671098. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0014-2999(98)00195-2.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gobbi M, Moia M, Pirona L, et al. (September 2002). "p-Methylthioamphetamine and 1-(m-chlorophenyl)piperazine, two non-neurotoxic 5-HT releasers in vivo, differ from neurotoxic amphetamine derivatives in their mode of action at 5-HT nerve endings in vitro". Journal of Neurochemistry 82 (6): 1435–43. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01073.x. PMID 12354291.

- ↑ http://facialneuralgia.org/ "Among strong pain-relieving drugs, analgesics like tramadol and some non-steroid antiphlogistic medicines like aspirin are widely used to cure trigeminal neuralgia."

- ↑ Rojas-Corrales, MO; Berrocoso, E; Gibert-Rahola, J; Micó, JA (2004). "Antidepressant-like effect of Tramadol and its enantiomers in reserpinized mice: comparative study with desipramine, fluvoxamine, venlafaxine and opiates". Journal of psycho-pharmacology 18 (3): 404–11. doi:10.1177/026988110401800305. PMID 15358985.

- ↑ Micó, JA; Ardid, D; Berrocoso, E; Eschalier, A (2006). "Antidepressants and pain". Trends in pharmacological sciences 27 (7): 348–54. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2006.05.004. PMID 16762426.

- ↑ Rojas-Corrales, MO; Gibert-Rahola, J; Micó, JA (1998). "Tramadol induces antidepressant-type effects in mice". Life sciences 63 (12): PL175–80. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00369-5. PMID 9749830.

- ↑ Hopwood, SE; Owesson, CA; Callado, LF; Mclaughlin, DP; Stamford, JA (2001). "Effects of chronic Tramadol on pre- and post-synaptic measures of mono-amine function". Journal of psycho-pharmacology 15 (3): 147–53. PMID 11565620.

- ↑ Rojas-Corrales MO, Gibert-Rahola J, Micó JA (1998). "Tramadol induces antidepressant-type effects in mice". Life Sciences 63 (12): PL175–80. doi:10.1016/S0024-3205(98)00369-5. PMID 9749830.

- ↑ Hopwood SE, Owesson CA, Callado LF, McLaughlin DP, Stamford JA (September 2001). "Effects of chronic tramadol on pre- and post-synaptic measures of monoamine function". Journal of Psychopharmacology 15 (3): 147–53. doi:10.1177/026988110101500301. PMID 11565620. http://jop.sagepub.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11565620.

- ↑ http://74.125.93.132/search?q=cache%3ApIw2Pm_16SMJ%3Awww.fda.gov%2Fdownloads%2FDrugs%2FguidanceComplianceRegulatoryinformation%2FEnforcementActivitiesbyFDA%2FWarningLettersandNoticeofViolationLetterstoPharmaceuticalCompanies%2FUCM153130.pdf+ultram+abuse+fda&hl=en

- ↑ Harati, Y; Gooch, C; Swenson, M; Edelman, S; Greene, D; Raskin, P; Donofrio, P; Cornblath, D et al. (1998). "Double-blind randomized trial of tramadol for the treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathy". Neurology 50 (6): 1842–6. PMID 9633738.

- ↑ Harati, Y; Gooch, C; Swenson, M; Edelman, SV; Greene, D; Raskin, P; Donofrio, P; Cornblath, D et al. (2000). "Maintenance of the long-term effectiveness of tramadol in treatment of the pain of diabetic neuropathy". Journal of diabetes and its complications 14 (2): 65–70. doi:10.1016/S1056-8727(00)00060-X. PMID 10959067.

- ↑ Göbel, H; Stadler, T (1997). "Treatment of post-herpes zoster pain with tramadol. Results of an open pilot study versus clomipramine with or without levomepromazine". Drugs 53 Suppl 2: 34–9. PMID 9190323.

- ↑ Boureau, F; Legallicier, P; Kabir-Ahmadi, M (2003). "Tramadol in post-herpetic neuralgia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Pain 104 (1-2): 323–31. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00020-4. PMID 12855342.

- ↑ Bennett, RM; Kamin, M; Karim, R; Rosenthal, N (2003). "Tramadol and acetaminophen combination tablets in the treatment of fibromyalgia pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study". The American journal of medicine 114 (7): 537–45. doi:10.1016/S0002-9343(03)00116-5. PMID 12753877.

- ↑ Lauerma, H; Markkula, J (1999). "Treatment of restless legs syndrome with tramadol: an open study". The Journal of clinical psychiatry 60 (4): 241–4. PMID 10221285.

- ↑ Sobey, PW; Parran Tv, TV; Grey, SF; Adelman, CL; Yu, J (2003). "The use of tramadol for acute heroin withdrawal: a comparison to clonidine". Journal of addictive diseases 22 (4): 13–25. PMID 14723475.

- ↑ Threlkeld, M; Parran, TV; Adelman, CA; Grey, SF; Yu, J; Yu, Jaehak (2006). "Tramadol versus buprenorphine for the management of acute heroin withdrawal: a retrospective matched cohort controlled study". The American journal on addictions 15 (2): 186–91. doi:10.1080/10550490500528712. PMID 16595358.

- ↑ Engindeniz, Z; Demircan, C; Karli, N; Armagan, E; Bulut, M; Aydin, T; Zarifoglu, M (2005). "Intramuscular tramadol vs. Diclofenac sodium for the treatment of acute migraine attacks in emergency department: a prospective, randomised, double-blind study". The journal of headache and pain 6 (3): 143–8. doi:10.1007/s10194-005-0169-y. PMID 16355295.

- ↑ Goldsmith, Toby D; Shapira, Nathan A; Keck, Paul E (1999). "Rapid Remission of OCD with Tramadol Hydrochloride". American Journal of Psychiatry 156 (4): 660. PMID 10200754. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/156/4/660a.

- ↑ Salem, EA; Wilson, SK; Bissada, NK; Delk, JR; Hellstrom, WJ; Cleves, MA (2008). "Tramadol HCL has promise in on-demand use to treat premature ejaculation". The journal of sexual medicine 5 (1): 188–93. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2006.00424.x. PMID 17362279.

- ↑ Brooks, Wendy C. (11 April 2008). "Tramadol". The Pet Health Library. Veterinary Information Network. http://www.veterinarypartner.com/Content.plx?P=A&A=1815&S=1&SourceID=42. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 http://www.fda.gov/cder/foi/label/2004/20281slr030,21123slr001_Ultram_lbl.pdf

- ↑ Willaschek, C; Wolter, E; Buchhorn, R (2009). "Tramadol withdrawal in a neonate after long-term analgesic treatment of the mother". European journal of clinical pharmacology 65 (4): 429–30. doi:10.1007/s00228-008-0598-z. PMID 19083210.

- ↑ http://toxnet.nlm.nih.gov/cgi-bin/sis/search/f?./temp/~4Ntv5b:1 United States National Library of Medicine]

- ↑ "Tramadol". MedlinePlus. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. 1 September 2008. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/druginfo/meds/a695011.html. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

- ↑ by Pseudome (2009-10-28). "Erowid Experience Vaults: Tramadol (Ultram) - Overdose - 81951". Erowid.org. http://www.erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=81951. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ by Rifter (2007-06-25). "Erowid Experience Vaults: Tramadol (Ultram) - My Seizures - 63922". Erowid.org. http://www.erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=63922. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ by angelsigh (2003-07-24). "Erowid Experience Vaults: Tramadol (Ultram) - My Four Months On It... - 13574". Erowid.org. http://www.erowid.org/experiences/exp.php?ID=13574. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Gardner, J. S.; Blough, D.; Drinkard, C. R.; Shatin, D.; Anderson, G.; Graham, D.; Alderfer, R. (2000). "Tramadol and Seizures: A Surveillance Study in a Managed Care Population". Pharmocotherapy 20 (12).

- ↑ Bryant et al. 1988; Rouveix 1992; cited by Collett, BJ (2001). "Chronic opioid therapy for non-cancer pain". British journal of anaesthesia 87 (1): 133–43. doi:10.1093/bja/87.1.133. PMID 11460802.

- ↑ Sacerdote, Paola; Bianchi, Mauro; Gaspani, Leda; Manfredi, Barbara; Maucione, Antonio; Terno, Giovanni; Ammatuna, Mario; Panerai, Alberto E (2000). "The Effects of Tramadol and Morphine on Immune Responses and Pain After Surgery in Cancer Patients". Anesthesia & Analgesia 90 (6): 1411. doi:10.1097/00000539-200006000-00028. PMID 10825330. http://www.anesthesia-analgesia.org/cgi/content/abstract/90/6/1411.

- ↑ Liu, Z; Gao, F; Tian, Y (2006). "Effects of morphine, fentanyl and tramadol on human immune response". Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Medical sciences = Hua zhong ke ji da xue xue bao. Yi xue Ying De wen ban = Huazhong keji daxue xuebao. Yixue Yingdewen ban 26 (4): 478–81. PMID 17120754.

- ↑ Sacerdote, P; Bianchi, M; Manfredi, B; Panerai, AE (1997). "Effects of tramadol on immune responses and nociceptive thresholds in mice". Pain 72 (3): 325–30. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00055-9. PMID 9313273.

- ↑ Maruta 1978; McNairy et al. 1984; cited by Collett, BJ (2001). "Chronic opioid therapy for non-cancer pain". British journal of anaesthesia 87 (1): 133–43. doi:10.1093/bja/87.1.133. PMID 11460802.

- ↑ Mullican, W. S.; Lacy, J. R. (2001). "Tramadol/Acetaminophen Comination Tablets and Codeine/Acetaminophen Combination Capsules for the Management of Chronic Pain: A Comparative Trial". Clinical Therapeutics 23 (9).

- ↑ Pharmaceutical Substances, Axel Kleemann, Jürgen Engel, Bernd Kutscher and Dieter Reichert, 4. ed. (2000) 2 volumes, Thieme-Verlag Stuttgart (Germany), p. 2085 bis 2086, ISBN 978-1-58890-031-9; since 2003 online with biannual actualizations.

- ↑ Zynovy Itov und Harold Meckler: A Practical Procedure for the Resolution of (+)- and (−)-Tramadol, Organic Process Research & Development 2000, 291-294.

- ↑ Burke D, Henderson DJ (April 2002). "Chirality: a blueprint for the future". British Journal of Anaesthesia 88 (4): 563–76. doi:10.1093/bja/88.4.563. PMID 12066734.

- ↑ Grond S, Sablotzki A (2004). "Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. La de la de da.". Clinical Pharmacokinetics 43 (13): 879–923. doi:10.2165/00003088-200443130-00004. PMID 15509185.

- ↑ Hennies HH, Friderichs E, Schneider J (July 1988). "Receptor binding, analgesic and antitussive potency of tramadol and other selected opioids". Arzneimittel-Forschung 38 (7): 877–80. PMID 2849950.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Frink MC, Hennies HH, Englberger W, Haurand M, Wilffert B (November 1996). "Influence of tramadol on neurotransmitter systems of the rat brain". Arzneimittel-Forschung 46 (11): 1029–36. PMID 8955860.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Hara K, Minami K, Sata T (May 2005). "The effects of tramadol and its metabolite on glycine, gamma-aminobutyric acidA, and N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Anesthesia and Analgesia 100 (5): 1400–5, table of contents. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000150961.24747.98. PMID 15845694.

- ↑ Ogata J, Minami K, Uezono Y, et al. (May 2004). "The inhibitory effects of tramadol on 5-hydroxytryptamine type 2C receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Anesthesia and Analgesia 98 (5): 1401–6, table of contents. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000108963.77623.A4. PMID 15105221. http://www.anesthesia-analgesia.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15105221.

- ↑ Shiraishi M, Minami K, Uezono Y, Yanagihara N, Shigematsu A, Shibuya I (May 2002). "Inhibitory effects of tramadol on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in adrenal chromaffin cells and in Xenopus oocytes expressing alpha 7 receptors". British Journal of Pharmacology 136 (2): 207–16. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0704703. PMID 12010769.

- ↑ Shiraishi M, Minami K, Uezono Y, Yanagihara N, Shigematsu A (October 2001). "Inhibition by tramadol of muscarinic receptor-induced responses in cultured adrenal medullary cells and in Xenopus laevis oocytes expressing cloned M1 receptors". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 299 (1): 255–60. PMID 11561087. http://jpet.aspetjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11561087.

- ↑ Shiga Y, Minami K, Shiraishi M, et al. (November 2002). "The inhibitory effects of tramadol on muscarinic receptor-induced responses in Xenopus oocytes expressing cloned M(3) receptors". Anesthesia and Analgesia 95 (5): 1269–73, table of contents. doi:10.1097/00000539-200211000-00031. PMID 12401609. http://www.anesthesia-analgesia.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12401609.

- ↑ Ogata, J; Minami, K; Uezono, Y; Okamoto, T; Shiraishi, M; Shigematsu, A; Ueta, Y (2004). "The inhibitory effects of tramadol on 5-hydroxytryptamine type 2C receptors expressed in Xenopus oocytes". Anesthesia and analgesia 98 (5): 1401–6, table of contents. PMID 15105221.

- ↑ Barsotti, CE; Mycyk, MB; Reyes, J (2003). "Withdrawal syndrome from tramadol hydrochloride". The American journal of emergency medicine 21 (1): 87–8. doi:10.1053/ajem.2003.50039. PMID 12563592.

- ↑ Choong, K; Ghiculescu, RA (2008). "Iatrogenic neuropsychiatric syndromes". Australian family physician 37 (8): 627–9. PMID 18704211.

- ↑ Ripamonti, C; Fagnoni, E; De Conno, F (2004). "Withdrawal syndrome after delayed tramadol intake". The American journal of psychiatry 161 (12): 2326–7. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2326. PMID 15569913.

- ↑ "Withdrawal syndrome and dependence: tramadol too". Prescrire international 12 (65): 99–100. 2003. PMID 12825576.

- ↑ Senay, EC; Adams, EH; Geller, A; Inciardi, JA; Muñoz, A; Schnoll, SH; Woody, GE; Cicero, TJ (2003). "Physical dependence on Ultram (tramadol hydrochloride): both opioid-like and atypical withdrawal symptoms occur". Drug and alcohol dependence 69 (3): 233–41. doi:10.1016/S0376-8716(02)00321-6. PMID 12633909.

- ↑ Rossi, 2004

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Kentucky Board of Pharmacy (8 December 2008). "Tramadol Listed as Schedule IV Substance in Kentucky". Press release. http://pharmacy.ky.gov/NR/rdonlyres/9A7E27E4-1D37-4F44-A542-C9DD5B487822/0/TramadolNotification.pdf. Retrieved 8 February 2009.

- ↑ Jovanović-Cupić, V; Martinović, Z; Nesić, N (2006). "Seizures associated with intoxication and abuse of tramadol". Clinical toxicology 44 (2): 143–6. doi:10.1080/1556365050014418. PMID 16615669.

- ↑ Rodriguez, RF; Bravo, LE; Castro, F; Montoya, O; Castillo, JM; Castillo, MP; Daza, P; Restrepo, JM et al. (2007). "Incidence of weak opioids adverse events in the management of cancer pain: a double-blind comparative trial". Journal of palliative medicine 10 (1): 56–60. doi:10.1089/jpm.2006.0117. PMID 17298254.

- ↑ Adams, EH; Breiner, S; Cicero, TJ; Geller, A; Inciardi, JA; Schnoll, SH; Senay, EC; Woody, GE (2006). "A comparison of the abuse liability of tramadol, NSAIDs, and Codeine in patients with chronic pain". Journal of pain and symptom management 31 (5): 465–76. doi:10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.10.006. PMID 16716877. http://paincenter.wustl.edu/c/BasicResearch/documents/CiceroJPain2006.pdf.

- ↑ Vorsanger, GJ; Xiang, J; Gana, TJ; Pascual, ML; Fleming, RR (2008). "Extended-release tramadol (tramadol ER) in the treatment of chronic low back pain". Journal of opioid management 4 (2): 87–97. PMID 18557165.

- ↑ Karhu D, El-Jammal A, Dupain T, Gaulin D, Bouchard S. Pharmacokinetics and dose proportionality of three tramadol Contramid OAD tablet strengths. Biopharm. Drug Dispos. 28: 323-330, 2007.

- ↑ Tjäderborn M, Jönsson AK, Hägg S, Ahlner J. Fatal unintentional intoxications with tramadol during 1995-2005. For. Sci. Int. 173: 107-111, 2007

- ↑ R. Baselt, Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man, 8th edition, Biomedical Publications, Foster City, CA, 2008, pp. 1573-1576.

- ↑ "New legislation aimed at the military". Buytramadolhcl.net. http://www.buytramadolhcl.net/new-legislation-aimed-at-the-military.html. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ Erowid

- ↑ "Substansen tramadol nu narkotikaklassad på samma sätt som kodein och dextropropoxifen - Läkemedelsverket". Lakemedelsverket.se. http://www.lakemedelsverket.se/Tpl/NewsPage____7342.aspx. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ USA. "Tramadol extended-release in the management of chronic pain". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2386353/. Retrieved 2010-04-18.

- ↑ US patent 6254887, Miller, Ronald Brown, et al., "Controlled Release Tramadol", issued 3 July 2001

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 FDA AccessData entry for Tramadol Hydrochloride. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ↑ US patent 7074430, Miller, Ronald Brown, et al., "Controlled Release Tramadol Tramadol Formulation", issued 11 July 2006

- ↑ Par Pharmaceutical (17 August 2009). "Par Pharmaceutical Wins on Invalidity in Ultram(R) ER Litigation". Press release. http://news.prnewswire.com/DisplayReleaseContent.aspx?ACCT=104&STORY=/www/story/08-17-2009/0005078446&EDATE=. Retrieved 29 September 2009.

External links

- Grünenthal website

- Medline Plus - Patient Information Medline Plus (A Service Of The U.S. National Library of Medicine)

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Tramadol

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|