Tiger

| Tiger | |

|---|---|

|

|

| A Bengal Tiger (P. tigris tigris) in India's Ranthambhore National Park. | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. tigris |

| Binomial name | |

| Panthera tigris (Linnaeus, 1758) |

|

| Subspecies | |

|

P. t. tigris |

|

|

|

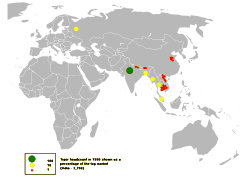

| Historical distribution of tigers (pale yellow) and 2006 (green).[2] | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Tigris striatus Severtzov, 1858 |

|

The tiger (Panthera tigris), a member of the Felidae family, is the largest of the four "big cats" in the genus Panthera.[4] Native to much of eastern and southern Asia, the tiger is an apex predator and an obligate carnivore. Reaching up to 3.3 metres (11 ft) in total length, weighing up to 300 kilograms (660 pounds), and having canines up to 4 inches long,[5] the larger tiger subspecies are comparable in size to the biggest extinct felids.[6][7] Aside from their great bulk and power, their most recognisable feature is a pattern of dark vertical stripes that overlays near-white to reddish-orange fur, with lighter underparts. The most numerous tiger subspecies is the Bengal tiger while the largest is the Siberian tiger.

Tigers have a lifespan of 10–15 years in the wild, but can live longer than 20 years in captivity.[8] They are highly adaptable and range from the Siberian taiga to open grasslands and tropical mangrove swamps.

They are territorial and generally solitary animals, often requiring large contiguous areas of habitat that support their prey demands. This, coupled with the fact that they are indigenous to some of the more densely populated places on earth, has caused significant conflicts with humans. Three of the nine subspecies of modern tiger have gone extinct, and the remaining six are classified as endangered, some critically so. The primary direct causes are habitat destruction, fragmentation and hunting.

Historically tigers have existed from Mesopotamia and the Caucasus throughout most of South and East Asia. Today the range of the species is radically reduced. While all surviving species are under formal protection, poaching, habitat destruction and inbreeding depression continue to threaten the tigers.

Tigers are among the most recognizable and popular of the world's charismatic megafauna. They have featured prominently in ancient mythology and folklore, and continue to be depicted in modern films and literature. Tigers appear on many flags and coats of arms, as mascots for sporting teams, and as the national animal of several Asian nations, including India.[9]

Contents |

Naming and etymology

The word "tiger" is taken from the Greek word "tigris", which is possibly derived from a Persian source meaning "arrow", a reference to the animal's speed and also the origin for the name of the Tigris river.[10][11] In American English, "tigress" was first recorded in 1611. It was one of the many species originally described by Linnaeus in his 18th century work, Systema Naturae: he called it Felis tigris.[3][12] The generic component of its scientific designation, Panthera tigris, is often presumed to derive from Greek pan- ("all") and theron ("beast"), but this may be a folk etymology. Although it came into English through the classical languages, panthera is probably of East Asian origin, meaning "the yellowish animal", or "whitish-yellow".[13]

Tigers rarely form groups (see below), but collective nouns sometimes used when they do are "streak".[14]

Range and habitat

In the past, tigers were found throughout Asia, from the Caucasus and the Caspian Sea to Siberia and Indonesia. Today the range of the tiger is only 7 percent of what it used to be. [15] Furthermore, within the past decade alone, the estimated area known to be occupied by tigers has declined 41 percent. [16]

During the 19th century, the tiger completely vanished from western Asia and became restricted to isolated pockets in the remaining parts of their range. Today, their range is fragmented, and certain parts degraded, and extends from India in the west to China and Southeast Asia in the east.[17] The northern limit is close to the Amur River in south eastern Siberia. The only large island inhabited by tigers today is Sumatra. Tigers vanished from Java and Bali during the 20th century. In Borneo they are known only from fossil remains.

Tiger habitats will usually include sufficient cover, proximity to water, and an abundance of prey. Bengal Tigers live in many types of forests, including wet; evergreen; the semi-evergreen of Assam and eastern Bengal; the mangrove forest of the Ganges Delta; the deciduous forest of Nepal, and the thorn forests of the Western Ghats. Compared to the lion, the tiger prefers denser vegetation, for which its camouflage colouring is ideally suited, and where a single predator is not at a disadvantage compared with the multiple felines in a pride.

Among the big cats, only the tiger and jaguar are strong swimmers; tigers are often found bathing in ponds, lakes, and rivers. Unlike other cats, which tend to avoid water, tigers actively seek it out. During the extreme heat of the day, they often cool off in pools. Tigers are excellent swimmers, able to swim up to 4 miles and carry dead prey across lakes.

Physical characteristics, taxonomy and evolution

The oldest remains of a tiger-like cat, called Panthera palaeosinensis, have been found in China and Java. This species lived about 2 million years ago, at the beginning of the Pleistocene, and was smaller than a modern tiger. The earliest fossils of true tigers are known from Java, and are between 1.6 and 1.8 million years old. Distinct fossils from the early and middle Pleistocene were also discovered in deposits from China, and Sumatra. A subspecies called the Trinil tiger (Panthera tigris trinilensis) lived about 1.2 million years ago and is known from fossils found at Trinil in Java.[18]

Tigers first reached India and northern Asia in the late Pleistocene, reaching eastern Beringia (but not the American Continent), Japan, and Sakhalin. Fossils found in Japan indicate that the local tigers were, like the surviving island subspecies, smaller than the mainland forms. This may be due to the phenomenon in which body size is related to environmental space (see insular dwarfism), or perhaps the availability of prey. Until the Holocene, tigers also lived in Borneo, as well as on the island of Palawan in the Philippines.[19]

Physical characteristics

Tigers are easy to recognise. They typically have rusty-reddish to brown-rusty coats, a whitish medial and ventral area, a white "fringe" that surrounds the face, and stripes that vary from brown or gray to pure black. The form and density of stripes differs between subspecies (as well as the ground coloration of the fur; for instance, Siberian tigers are usually paler than other tiger subspecies), but most tigers have over 100 stripes.

The pattern of stripes is unique to each animal, and thus could potentially be used to identify individuals, much in the same way that fingerprints are used to identify people. This is not, however, a preferred method of identification, due to the difficulty of recording the stripe pattern of a wild tiger. It seems likely that the function of stripes is camouflage, serving to help tigers conceal themselves amongst the dappled shadows and long grass of their environment as they stalk their prey. The stripe pattern is also found on the skin of the tiger. If a tiger were to be shaved, its distinctive camouflage pattern would be preserved.

Like other big cats, tigers have a white spot on the backs of their ears. These spots, called ocelli, serve a social function, by communicating the animal's mental state to conspecifics in the gloom of dense forest or in tall grass.

Tigers have the additional distinction of being the heaviest cats found in the wild.[20] They also have powerfully built legs and shoulders, with the result that they, like lions, have the ability to pull down prey substantially heavier than themselves. However, the subspecies differ markedly in size, tending to increase proportionally with latitude, as predicted by Bergmann's Rule.

Large male Siberian Tigers (Panthera tigris altaica) can reach a total length of 3.5 m "over curves" (3.3 m. "between pegs") and a weight of 306 kilograms,[21]. This is considerably larger than the sizes reached by island-dwelling tigers such as the Sumatran, the smallest living subspecies, with a body weight of only 75–140 kg.[21]

Tigresses are smaller than the males in each subspecies, although the size difference between male and female tigers tends to be more pronounced in the larger subspecies of tiger, with males weighing up to 1.7 times more than the females.[22] In addition, male tigers have wider forepaw pads than females. Biologists use this difference to determine gender based on tiger tracks.[23] The skull of the tiger is very similar to that of the lion, though the frontal region is usually not as depressed or flattened, with a slightly longer postorbital region. The skull of a lion has broader nasal openings. However, due to the amount of skull variation in the two species, usually, only the structure of the lower jaw can be used as a reliable indicator of species.[24]

Tigers have round pupils and yellow irises (except for the blue eyes of white tigers). Due to a retinal adaptation that reflects light back to the retina, the night vision of tigers is six times better than that of humans.[25]

Subspecies

There are nine recent subspecies of tiger, three of which are extinct. Their historical range (severely diminished today) ran through Bangladesh, Siberia, Iran, Afghanistan, India, China, and southeast Asia, including some Indonesian islands. The surviving subspecies, in descending order of wild population, are:

- The Bengal tiger or the Royal Bengal tiger (Panthera tigris tigris) is the most common subspecies of tiger and is found primarily in India and Bangladesh.[26] It lives in varied habitats: grasslands, subtropical and tropical rainforests, scrub forests, wet and dry deciduous forests, and mangroves. Males in the wild usually weigh 205 to 227 kg (450 to 500 lb), while the average female will weigh about 141 kg.[27] However, the northern Indian and the Nepalese Bengal tigers are somewhat bulkier than those found in the south of the Indian Subcontinent, with males averaging around 235 kilograms (520 lb).[27] While conservationists already believed the population to be below 2,000,[28] the most recent audit by the Indian Government's National Tiger Conservation Authority has estimated the number at just 1,411 wild tigers (1165–1657 allowing for statistical error), a drop of 60% in the past decade.[29] Since 1972, there has been a massive wildlife conservation project, known as Project Tiger, to protect the Bengal tiger. Despite increased efforts by Indian officials, poaching remains rampant and at least one Tiger Reserve (Sariska Tiger Reserve) has lost its entire tiger population to poaching.[30]

- The Indochinese Tiger (Panthera tigris corbetti), also called Corbett's tiger, is found in Cambodia, China, Laos, Burma, Thailand, and Vietnam. These tigers are smaller and darker than Bengal tigers: Males weigh from 150–190 kg (330–420 lb) while females are smaller at 110–140 kg (240–310 lb). Their preferred habitat is forests in mountainous or hilly regions. Estimates of the Indochinese tiger population vary between 1,200 to 1,800, with only several hundred left in the wild. All existing populations are at extreme risk from poaching, prey depletion as a result of poaching of primary prey species such as deer and wild pigs, habitat fragmentation and inbreeding. In Vietnam, almost three-quarters of the tigers killed provide stock for Chinese pharmacies.

- The Malayan Tiger (Panthera tigris jacksoni), exclusively found in the southern part of the Malay Peninsula, was not considered a subspecies in its own right until 2004. The new classification came about after a study by Luo et al. from the Laboratory of Genomic Diversity Study,[31] part of the National Cancer Institute of the United States. Recent counts showed there are 600–800 tigers in the wild, making it the third largest tiger population, behind the Bengal tiger and the Indochinese tiger. The Malayan tiger is the smallest of the mainland tiger subspecies, and the second smallest living subspecies, with males averaging about 120 kg and females about 100 kg in weight. The Malayan tiger is a national icon in Malaysia, appearing on its coat of arms and in logos of Malaysian institutions, such as Maybank.

- The Sumatran Tiger (Panthera tigris sumatrae) is found only on the Indonesian island of Sumatra, and is critically endangered.[32] It is the smallest of all living tiger subspecies, with adult males weighing between 100–140 kg (220–310 lb) and females 75–110 kg (170–240 lb).[33] Their small size is an adaptation to the thick, dense forests of the island of Sumatra where they reside, as well as the smaller-sized prey. The wild population is estimated at between 400 and 500, seen chiefly in the island's national parks. Recent genetic testing has revealed the presence of unique genetic markers, indicating that it may develop into a separate species, if it does not go extinct.[34] This has led to suggestions that Sumatran tigers should have greater priority for conservation than any other subspecies. While habitat destruction is the main threat to existing tiger population (logging continues even in the supposedly protected national parks), 66 tigers were recorded as being shot and killed between 1998 and 2000, or nearly 20% of the total population.

- The Siberian tiger (Panthera tigris altaica), also known as the Amur, Manchurian, Altaic, Korean or North China tiger, which is the most northernmost subspecies, is confined to the Amur-Ussuri region of Primorsky Krai and Khabarovsk Krai in far eastern Siberia, where it is now protected. [35] The largest subspecies of tiger, it has a head and body length of 160–180 cm for females and 190–230+ cm for males, plus a tail of about 60–110 cm long (about 270–330 cm in total length) and an average weight of around 227 kilograms (500 lb) for males,[27] the Amur tiger is also noted for its thick coat, distinguished by a paler golden hue and fewer stripes. The heaviest wild Siberian tiger on record weighed in at 384 kg,[36] but according to Mazak these giants are not confirmed via reliable references.[21] Even so, a six-month old Siberian tiger can be as big as a fully grown leopard. The last two censuses (1996 and 2005) found 450–500 Amur tigers within their single, and more or less continuous, range making it one of the largest undivided tiger populations in the world. Genetic research in 2009 demonstrated that the Siberian tiger, and the western "Caspian tiger" (once thought to have been a separate subspecies that became extinct in the wild in the late 1950s[37][38]) are actually the same subspecies, since the separation of the two populations may have occurred as recently as the past century due to human intervention.[39]

- The South China Tiger (Panthera tigris amoyensis), also known as the Amoy or Xiamen tiger, is the most critically endangered subspecies of tiger and is listed as one of the 10 most endangered animals in the world.[40] One of the smaller tiger subspecies, the length of the South China tiger ranges from 2.2–2.6 m (87–100 in) for both males and females. Males weigh between 127 and 177 kg (280 and 390 lb) while females weigh between 100 and 118 kg (220 and 260 lb). From 1983 to 2007, no South China tigers were sighted.[41] In 2007 a farmer spotted a tiger and handed in photographs to the authorities as proof.[41][42] The photographs in question, however, were later exposed as fake, copied from a Chinese calendar and digitally altered, and the “sighting” turned into a massive scandal.[43][44][45]

In 1977, the Chinese government passed a law banning the killing of wild tigers, but this may have been too late to save the subspecies, since it is possibly already extinct in the wild. There are currently 59 known captive South China tigers, all within China, but these are known to be descended from only six animals. Thus, the genetic diversity required to maintain the subspecies may no longer exist. Currently, there are breeding efforts to reintroduce these tigers to the wild.

Extinct subspecies

- The Bali Tiger (Panthera tigris balica) was limited to the island of Bali. They were the smallest of all tiger subspecies, with a weight of 90–100 kg in males and 65–80 kg in females.[21] These tigers were hunted to extinction—the last Balinese tiger is thought to have been killed at Sumbar Kima, West Bali on 27 September 1937; this was an adult female. No Balinese tiger was ever held in captivity. The tiger still plays an important role in Balinese Hinduism.

- The Javan tiger (Panthera tigris sondaica) was limited to the Indonesian island of Java. It now seems likely that this subspecies became extinct in the 1980s, as a result of hunting and habitat destruction, but the extinction of this subspecies was extremely probable from the 1950s onwards (when it is thought that fewer than 25 tigers remained in the wild). The last confirmed specimen was sighted in 1979, but there were a few reported sightings during the 1990s.[46][47] With a weight of 100–141 kg for males and 75–115 kg for females, the Javan tiger was one of the smaller subspecies, approximately the same size as the Sumatran tiger.

- The Caspian Tiger (formerly Panthera tigris virgata), also known as the Persian tiger or Turanian tiger was the westernmost population of Siberian tiger, found in Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Turkey, Mongolia, Kazakhstan, the Caucasus, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan until it apparently became extinct in the late 1950s, though there have been several alleged more recent sightings of the tiger.[38] Though originally thought to have been a distinct subspecies, genetic research in 2009 suggest that the animal was largely identical to the Siberian tiger.[39]

Hybrids

Hybridisation among the big cats, including the tiger, was first conceptualised in the 19th century, when zoos were particularly interested in the pursuit of finding oddities to display for financial gain.[48] Lions have been known to breed with tigers (most often the Amur and Bengal subspecies) to create hybrids called ligers and tigons.[49] Such hybrids were once commonly bred in zoos, but this is now discouraged due to the emphasis on conserving species and subspecies. Hybrids are still bred in private menageries and in zoos in China.

The liger is a cross between a male lion and a tigress.[50] Because the lion sire passes on a growth-promoting gene, but the corresponding growth-inhibiting gene from the female tiger is absent, ligers grow far larger than either parent. They share physical and behavioural qualities of both parent species (spots and stripes on a sandy background). Male ligers are sterile, but female ligers are often fertile. Males have about a 50% chance of having a mane, but, even if they do, their manes will be only around half the size of that of a pure lion. Ligers are typically between 10 to 12 feet in length, and can be between 800 and 1,000 pounds or more.[50]

The less common tigon is a cross between the lioness and the male tiger.[51]

Colour variations

White tigers

There is a well-known mutation that produces the white tiger, technically known as chinchilla albinistic,[52] an animal which is rare in the wild, but widely bred in zoos due to its popularity. Breeding of white tigers will often lead to inbreeding (as the trait is recessive). Many initiatives have taken place in white and orange tiger mating in an attempt to remedy the issue, often mixing subspecies in the process. Such inbreeding has led to white tigers having a greater likelihood of being born with physical defects, such as cleft palates and scoliosis (curvature of the spine).[53][54] Furthermore, white tigers are prone to having crossed eyes (a condition known as strabismus). Even apparently healthy white tigers generally do not live as long as their orange counterparts. Recordings of white tigers were first made in the early 19th century.[55] They can only occur when both parents carry the rare gene found in white tigers; this gene has been calculated to occur in only one in every 10,000 births. The white tiger is not a separate sub-species, but only a colour variation; since the only white tigers that have been observed in the wild have been Bengal tigers[56] (and all white tigers in captivity are at least part Bengal), it is commonly thought that the recessive gene that causes the white colouring is probably carried only by Bengal tigers, although the reasons for this are not known.[53][57] Nor are they in any way more endangered than tigers are generally, this being a common misconception. Another misconception is that white tigers are albinos, despite the fact that pigment is evident in the white tiger's stripes. They are distinct not only because of their white hue; they also have blue eyes and pink noses.

Golden tabby tigers

In addition, another recessive gene may create a very unusual "golden tabby" colour variation, sometimes known as "strawberry." Golden tabby tigers have light gold fur, pale legs and faint orange stripes. Their fur tends to be much thicker than normal.[58] There are extremely few golden tabby tigers in captivity, around 30 in all. Like white tigers, strawberry tigers are invariably at least part Bengal. Some golden tabby tigers, called heterozygous tigers, carry the white tiger gene, and when two such tigers are mated, can produce some stripeless white offspring. Both white and golden tabby tigers tend to be larger than average Bengal tigers.

Other colour variations

There are also unconfirmed reports of a "blue" or slate-coloured tiger, the Maltese Tiger, and largely or totally black tigers, and these are assumed, if real, to be intermittent mutations rather than distinct species.[52]

Biology and behaviour

Territorial behaviour

Tigers are essentially solitary and territorial animals. The size of a tiger's home range mainly depends on prey abundance, and, in the case of male tigers, on access to females. A tigress may have a territory of 20 square kilometres, while the territories of males are much larger, covering 60–100 km2. The range of a male tends to overlap those of several females.

The relationships between individuals can be quite complex, and it appears that there is no set "rule" that tigers follow with regards to territorial rights and infringing territories. For instance, although for the most part tigers avoid each other, both male and female tigers have been documented sharing kills. George Schaller observed a male tiger share a kill with two females and four cubs. Females are often reluctant to let males near their cubs, but Schaller saw that these females made no effort to protect or keep their cubs from the male, suggesting that the male might have been the father of the cubs. In contrast to male lions, male tigers will allow the females and cubs to feed on the kill first. Furthermore, tigers seem to behave relatively amicably when sharing kills, in contrast to lions, which tend to squabble and fight. Unrelated tigers have also been observed feeding on prey together. The following quotation is from Stephen Mills' book Tiger, as he describes an event witnessed by Valmik Thapar and Fateh Singh Rathore in Ranthambhore:[59]

A dominant tigress they called Padmini killed a 250 kg (550-lb) male nilgai – a very large antelope. They found her at the kill just after dawn with her three 14-month-old cubs and they watched uninterrupted for the next ten hours. During this period the family was joined by two adult females and one adult male – all offspring from Padmini's previous litters and by two unrelated tigers, one female the other unidentified. By three o'clock there were no fewer than nine tigers round the kill.

When young female tigers first establish a territory, they tend to do so fairly close to their mother's area. The overlap between the female and her mother's territory tends to wane with increasing time. Males, however, wander further than their female counterparts, and set out at a younger age to mark out their own area. A young male will acquire territory either by seeking out a range devoid of other male tigers, or by living as a transient in another male's territory until he is old and strong enough to challenge the resident male. The highest mortality rate (30–35% per year) amongst adult tigers occurs for young male tigers who have just left their natal area, seeking out territories of their own.[60]

Male tigers are generally more intolerant of other males within their territory than females are of other females. For the most part, however, territorial disputes are usually solved by displays of intimidation, rather than outright aggression. Several such incidents have been observed, in which the subordinate tiger yielded defeat by rolling onto its back, showing its belly in a submissive posture.[61] Once dominance has been established, a male may actually tolerate a subordinate within his range, as long as they do not live in too close quarters.[60] The most violent disputes tend to occur between two males when a female is in oestrus, and may result in the death of one of the males, although this is a rare occurrence.[60][62]

To identify his territory, the male marks trees by spraying of urine and anal gland secretions, as well as marking trails with scat. Males show a grimacing face, called the Flehmen response, when identifying a female's reproductive condition by sniffing their urine markings. Like the other Panthera cats, tigers can roar. Tigers will roar for both aggressive and non-aggressive reasons. Other tiger vocal communications include moans, hisses, growls and chuffs.

Tigers have been studied in the wild using a variety of techniques. The populations of tigers were estimated in the past using plaster casts of their pugmarks. This method was found faulty[63] and attempts were made to use camera trapping instead. Newer techniques based on DNA from their scat are also being evaluated. Radio collaring has also been a popular approach to tracking them for study in the wild.

Hunting and diet

In the wild, tigers mostly feed on larger and medium sized animals. Sambar, gaur, chital, barasingha, wild boar, nilgai and both water buffalo and domestic buffalo are the tiger's favoured prey in India. Sometimes, they also prey on leopards, pythons, sloth bears and crocodiles. In Siberia the main prey species are manchurian wapiti, wild boar, sika deer, moose, roe deer, and musk deer. In Sumatra Sambar, muntjac, wild boar, and malayan tapir are preyed on. In the former Caspian tiger's range, prey included saiga antelope, camels, caucasian wisent, yak, and wild horses. Like many predators, they are opportunistic and will eat much smaller prey, such as monkeys, peafowls, hares, and fish.

Adult elephants are too large to serve as common prey, but conflicts between tigers and elephants do sometimes take place. A case where a tiger killed an adult Indian Rhinoceros has been observed. Young elephant and rhino calves are occasionally taken. Tigers also sometimes prey on domestic animals such as dogs, cows, horses, and donkeys. These individuals are termed cattle-lifters or cattle-killers in contrast to typical game-killers.[64]

Old tigers, or those wounded and rendered incapable of catching their natural prey, have turned into man-eaters; this pattern has recurred frequently across India. An exceptional case is that of the Sundarbans, where healthy tigers prey upon fishermen and villagers in search of forest produce, humans thereby forming a minor part of the tiger's diet.[65] Tigers will occasionally eat vegetation for dietary fiber, the fruit of the Slow Match Tree being favoured.[64]

Tigers are thought to be nocturnal predators, hunting at night.[66] However, in areas where humans are absent, they have been observed via remote controlled, hidden cameras hunting during the daylight hours[67]. They generally hunt alone and ambush their prey as most other cats do, overpowering them from any angle, using their body size and strength to knock large prey off balance. Even with their great masses, tigers can reach speeds of about 49–65 kilometres per hour (35–40 miles per hour), although they can only do so in short bursts, since they have relatively little stamina; consequently, tigers must be relatively close to their prey before they break their cover. Tigers have great leaping ability; horizontal leaps of up to 10 metres have been reported, although leaps of around half this amount are more typical. However, only one in twenty hunts ends in a successful kill.[66]

When hunting large prey, tigers prefer to bite the throat and use their forelimbs to hold onto the prey, bringing it to the ground. The tiger remains latched onto the neck until its prey dies of strangulation.[68] By this method, gaurs and water buffalos weighing over a ton have been killed by tigers weighing about a sixth as much.[69] With small prey, the tiger bites the nape, often breaking the spinal cord, piercing the windpipe, or severing the jugular vein or common carotid artery.[70] Though rarely observed, some tigers have been recorded to kill prey by swiping with their paws, which are powerful enough to smash the skulls of domestic cattle,[64] and break the backs of sloth bears.[71]

During the 1980s, a tiger named "Genghis" in Ranthambhore National Park was observed frequently hunting prey through deep lake water,[72] a pattern of behaviour that had not been previously witnessed in over 200 years of observations. Moreover, he appeared to be extraordinarily successful for a tiger, with as many as 20% of hunts ending in a kill.

Reproduction

Mating can occur all year round, but is generally more common between November and April.[73] A female is only receptive for a few days and mating is frequent during that time period. A pair will copulate frequently and noisily, like other cats. The gestation period is 16 weeks. The litter size usually consists of around 3–4 cubs of about 1 kilogram (2.2 lb) each, which are born blind and helpless. The females rear them alone, sheltering them in dens such as thickets and rocky crevices. The father of the cubs generally takes no part in rearing them. Unrelated wandering male tigers may even kill cubs to make the female receptive, since the tigress may give birth to another litter within 5 months if the cubs of the previous litter are lost.[73] The mortality rate of tiger cubs is fairly high – approximately half do not survive to be more than two years old.[73]

There is generally a dominant cub in each litter, which tends to be male but may be of either sex.[72] This cub generally dominates its siblings during play and tends to be more active, leaving its mother earlier than usual. At 8 weeks, the cubs are ready to follow their mother out of the den, although they don't travel with her as she roams her territory until they are older. The cubs become independent around 18 months of age, but it is not until they are around 2–2½ years old that they leave their mother. Females reach sexual maturity at 3–4 years, whereas males reach sexual maturity at 4–5 years.[73]

Over the course of her life, a female tiger will give birth to an approximately equal number of male and female cubs. Tigers breed well in captivity, and the captive population in the United States may rival the wild population of the world.[74]

Interspecific predatory relationships

Tigers may kill such formidable predators as leopards, pythons and even crocodiles on occasion,[75][76][77] although predators typically avoid one another. When seized by a crocodile, a tiger will strike at the reptile's eyes with its paws.[64] Pythons have been known to kill tigers.[78] Leopards dodge competition from tigers by hunting in different times of the day and hunting different prey.[79] With relatively abundant prey, tigers and leopards were seen to successfully coexist without competitive exclusion or inter-species dominance hierarchies that may be more common to the savanna.[80] Tigers have been known to suppress wolf populations in areas where the two species coexist.[81][82] Dhole packs have been observed to attack and kill tigers in disputes over food, though not usually without heavy losses.[71] Lone golden jackals expelled from their pack have been known to form commensal relationships with tigers. These solitary jackals, known as kol-bahl, will attach themselves to a particular tiger, trailing it at a safe distance in order to feed on the big cat's kills. A kol-bahl will even alert a tiger to a kill with a loud pheal. Tigers have been known to tolerate these jackals: one report describes how a jackal confidently walked in and out between three tigers walking together a few feet away from each other.[83] Siberian tigers and brown bears can be competitors and usually avoid confrontation; however, tigers will kill bear cubs and even some adults on occasion. Bears (Asiatic black bears and brown bears) make up 5–8% of the tiger's diet in the Russian Far East.[21] There are also records of brown bears killing tigers, either in self defense or in disputes over kills.[24] Some bears emerging from hibernation will try to steal tigers' kills, although the tiger will sometimes defend its kill. Sloth bears are quite aggressive and will sometimes drive young tigers away from their kills, although it is more common for Bengal tigers to prey on sloth bears.[21]

Conservation efforts

Poaching for fur and destruction of habitat have greatly reduced tiger populations in the wild. At the start of the 20th century, it is estimated there were over 100,000 tigers in the world but the population has dwindled to about 2,000 in the wild.[84] Some estimates suggest the population is even lower, with some at less than 2,500 mature breeding individuals, with no subpopulation containing more than 250 mature breeding individuals.[85]

India

India is home to the world's largest population of tigers in the wild.[87] According to the World Wildlife Fund, of the 3,500 tigers around the world, 1,400 are found in India. Only 11 percent of original Indian tiger habitat remains, and it is becoming significantly fragmented and often degraded.[88] [89]

A major concerted conservation effort, known as Project Tiger, has been underway since 1973, initially spearheaded by Indira Gandhi. The fundamental accomplishment has been the establishment of over 25 well-monitored tiger reserves in reclaimed land where human development is categorically forbidden. The program has been credited with tripling the number of wild Bengal tigers from roughly 1,200 in 1973 to over 3,500 in the 1990s. However, a tiger census carried out in 2007, whose report was published on February 12, 2008, stated that the wild tiger population in India declined by 60% to approximately 1,411.[90] It is noted in the report that the decrease of tiger population can be attributed directly to poaching.[91]

Following the release of the report, the Indian government pledged $153 million to further fund the Project Tiger initiative, set-up a Tiger Protection Force to combat poachers, and fund the relocation of up to 200,000 villagers to minimise human-tiger interaction.[92] Additionally, eight new tiger reserves in India are being set up.[93] Indian officials successfully started a project to reintroduce the tigers into the Sariska Tiger Reserve.[94] The Ranthambore National Park is often cited as a major success by Indian officials against poaching.[95]

Tigers Forever is a collaboration between the Wildlife Conservation Society and Panthera Corporation to serve as both a science-based action plan and a business model to ensure that tigers live in the wild forever. Initial field sites of Tigers Forever include the world’s largest tiger reserve, the 21,756 km2 Hukaung Valley in Myanmar, the Western Ghats in India, Thailand’s Huai Khai Khaeng-Thung Yai protected areas, and other sites in Laos PDR, Cambodia, the Russian Far East and China covering approximately 260,000 km2 of critical tiger habitat. [96] [97]

Russia

The Siberian tiger was on the brink of extinction with only about 40 animals in the wild in the 1940s. Under the Soviet Union, anti-poaching controls were strict and a network of protected zones (zapovedniks) were instituted, leading to a rise in the population to several hundred. Poaching again became a problem in the 1990s, when the economy of Russia collapsed, local hunters had access to a formerly sealed off lucrative Chinese market, and logging in the region increased. While an improvement in the local economy has led to greater resources being invested in conservation efforts, an increase of economic activity has led to an increased rate of development and deforestation. The major obstacle in preserving the species is the enormous territory individual tigers require (up to 450 km2 needed by a single female and more for a single male).[98] [20] Current conservation efforts are led by local governments and NGO's in consort with international organisations, such as the World Wide Fund and the Wildlife Conservation Society.[20] The competitive exclusion of wolves by tigers has been used by Russian conservationists to convince hunters in the Far East to tolerate the big cats, as they limit ungulate populations less than wolves, and are effective in controlling the latter's numbers.[99] Currently, there are about 400–550 animals in the wild.

Tibet

In Tibet, tiger and leopard pelts have traditionally been used in various ceremonies and costumes. In January 2006 the Dalai Lama preached a ruling against using, selling, or buying wild animals, their products, or derivatives. It has yet to be seen whether this will result in a long-term slump in the demand for poached tiger and leopard skins.[100][101][102]

Rewilding

The first attempt at rewilding was by Indian conservationist Billy Arjan Singh, who reared a zoo-born tigress named Tara, and released her in the wilds of Dudhwa National Park in 1978. This was soon followed by a large number of people being eaten by a tigress who was later shot. Government officials claim that this tigress was Tara, an assertion hotly contested by Singh and conservationists. Later on, this rewilding gained further disrepute when it was found that the local gene pool had been sullied by Tara's introduction as she was partly Siberian tiger, a fact not known at the time of release, ostensibly due to poor record-keeping at Twycross Zoo, where she had been raised.[103][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112]

Save China's Tigers

The organisation Save China's Tigers, working with the Wildlife Research Centre of the State Forestry Administration of China and the Chinese Tigers South Africa Trust, secured an agreement on the reintroduction of Chinese tigers into the wild. The agreement, which was signed in Beijing on 26 November 2002, calls for the establishment of a Chinese tiger conservation model through the creation of a pilot reserve in China where indigenous wildlife, including the South China Tiger, will be reintroduced. Save China's Tigers aims to rewild the critically endangered South China Tiger by bringing a few captive-bred individuals to South Africa for rehabilitation training for them to regain their hunting instincts. At the same time, a pilot reserve in China is being set-up and the Tigers will be relocated and release back in China when the reserve in China is ready.[113] The offspring of the trained tigers will be released into the pilot reserves in China, while the original animals will stay in South Africa to continue breeding.[114]

The reason South Africa was chosen is because it is able to provide expertise and resources, land and game for the South China tigers. The South China Tigers of the project has since been successfully rewilded and are fully capable of hunting and surviving on their own.[113] This project is also very successful in the breeding of these rewilded South China Tigers and 5 cubs have been born in the project, these cubs of the 2nd generation would be able to learn their survival skills from their successfully rewilded mothers directly.[115]

It is hoped that in 2010, the Chinese year of the Tiger, the first batch of rewilded South China Tigers can be sent back to China from South Africa, and be released into the wild.[116]

Relation with humans

Tiger as prey

The tiger has been one of the Big Five game animals of Asia. Tiger hunting took place on a large scale in the early nineteenth and twentieth centuries, being a recognised and admired sport by the British in colonial India as well as the maharajas and aristocratic class of the erstwhile princely states of pre-independence India. Tiger hunting was done by some hunters on foot; others sat up on machans with a goat or buffalo tied out as bait; yet others on elephant-back.[117] In some cases, villagers beating drums were organised to drive the animals into the killing zone. Elaborate instructions were available for the skinning of tigers and there were taxidermists who specialised in the preparation of tiger skins.

Man-eating tigers

Although humans are not regular prey for tigers, they have killed more people than any other cat, particularly in areas where population growth, logging, and farming have put pressure on tiger habitats. Most man-eating tigers are old and missing teeth, acquiring a taste for humans because of their inability to capture preferred prey.[118] Almost all tigers that are identified as man-eaters are quickly captured, shot, or poisoned. Unlike man-eating leopards, even established man-eating tigers will seldom enter human settlements, usually remaining at village outskirts.[119] Nevertheless, attacks in human villages do occur.[120] Man-eaters have been a particular problem in India and Bangladesh, especially in Kumaon, Garhwal and the Sundarbans mangrove swamps of Bengal, where some healthy tigers have been known to hunt humans. Because of rapid habitat loss due to climate change, tiger attacks have increased in the Sundarbans.[121]

A female tiger Tatiana escaped from her enclosure in the San Francisco Zoo, killing one person and seriously injuring two more before being shot and killed by the police. The enclosure had walls that were lower than they were legally required to be, allowing the tiger to climb the wall and escape.

Traditional Asian medicine

Many people in China have a belief that various tiger parts have medicinal properties, including as pain killers and aphrodisiacs.[122] There is no scientific evidence to support these beliefs. The use of tiger parts in pharmaceutical drugs in China is already banned, and the government has made some offenses in connection with tiger poaching punishable by death. Furthermore, all trade in tiger parts is illegal under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora and a domestic trade ban has been in place in China since 1993. Still, there are a number of tiger farms in the country specialising in breeding the cats for profit. It is estimated that between 5,000 and 10,000 captive-bred, semi-tame animals live in these farms today.[123][124][125]

As pets

The Association of Zoos and Aquariums estimates that up to 12,000 tigers are being kept as private pets in the USA, significantly more than the world's entire wild population, 4,000 are believed to be in captivity in Texas alone.

Part of the reason for America's enormous tiger population relates to legislation. Only nineteen states have banned private ownership of tigers, fifteen require only a license, and sixteen states have no regulations at all.[126]

The success of breeding programmes at American zoos and circuses led to an overabundance of cubs in the 1980s and 1990s, which drove down prices for the animals. The SPCA estimate there are now 500 lions, tigers and other big cats in private ownership just in the Houston area.{{[127]=December 2009}}

In the 1983 film Scarface, the protagonist, Tony Montana, aspires to obtaining all the exterior trappings of the American Dream, which in the character's opinion included keeping a pet tiger on his property.

Cultural depictions

The tiger replaces the lion as King of the Beasts in cultures of eastern Asia,[128] representing royalty, fearlessness and wrath.[129] Its forehead has a marking which resembles the Chinese character 王, which means "king"; consequently, many cartoon depictions of tigers in China and Korea are drawn with 王 on their forehead.

Of great importance in Chinese myth and culture, the tiger is one of the 12 Chinese zodiac animals. Also in various Chinese art and martial art, the tiger is depicted as an earth symbol and equal rival of the Chinese dragon- the two representing matter and spirit respectively. In fact, the Southern Chinese martial art Hung Ga is based on the movements of the Tiger and the Crane. In Imperial China, a tiger was the personification of war and often represented the highest army general (or present day defense secretary),[129] while the emperor and empress were represented by a dragon and phoenix, respectively. The White Tiger (Chinese: 白虎; pinyin: Bái Hǔ) is one of the Four Symbols of the Chinese constellations. It is sometimes called the White Tiger of the West (西方白虎), and it represents the west and the autumn season.[129]

In Buddhism, it is also one of the Three Senseless Creatures, symbolising anger, with the monkey representing greed and the deer lovesickness.[129]

The Tungusic people considered the Siberian tiger a near-deity and often referred to it as "Grandfather" or "Old man". The Udege and Nanai called it "Amba". The Manchu considered the Siberian tiger as Hu Lin, the king.[23]

The widely worshiped Hindu goddess Durga, an aspect of Devi-Parvati, is a ten-armed warrior who rides the tigress (or lioness) Damon into battle. In southern India the god Ayyappan was associated with a tiger.[130]

The weretiger replaces the werewolf in shapeshifting folklore in Asia;[131] in India they were evil sorcerers while in Indonesia and Malaysia they were somewhat more benign.[132]

The tiger continues to be a subject in literature; both Rudyard Kipling, in The Jungle Book, and William Blake, in Songs of Experience, depict the tiger as a menacing and fearful animal. In The Jungle Book, the tiger, Shere Khan, is the wicked mortal enemy of the protagonist, Mowgli. However, other depictions are more benign: Tigger, the tiger from A. A. Milne's Winnie-the-Pooh stories, is cuddly and likable. In the Man Booker Prize winning novel "Life of Pi", the protagonist, Pi Patel, sole human survivor of a ship wreck in the Pacific Ocean, befriends another survivor: a large Bengal Tiger. The famous comic strip Calvin and Hobbes features Calvin and his stuffed tiger, Hobbes. A tiger is also featured on the cover of the popular cereal Frosted Flakes (also marketed as "Frosties") bearing the name "Tony the Tiger".

The Tiger is the national animal of Bangladesh, Nepal, India[133] (Bengal Tiger), Malaysia (Malayan Tiger), North Korea and South Korea (Siberian Tiger).

World's favourite animal

In a poll conducted by Animal Planet, the tiger was voted the world's favourite animal, narrowly beating the dog. More than 50,000 viewers from 73 countries voted in the poll. Tigers received 21% of the vote, dogs 20%, dolphins 13%, horses 10%, lions 9%, snakes 8%, followed by elephants, chimpanzees, orangutans and whales.[134][135][136][137]

Animal behaviourist Candy d'Sa, who worked with Animal Planet on the list, said: "We can relate to the tiger, as it is fierce and commanding on the outside, but noble and discerning on the inside".[134]

Callum Rankine, international species officer at the World Wildlife Federation conservation charity, said the result gave him hope. "If people are voting tigers as their favourite animal, it means they recognise their importance, and hopefully the need to ensure their survival," he said.[134]

See also

- 21st Century Tiger, information about tigers and conservation projects

- Panthera Corporation, big cat conservation organization

- Siegfried & Roy, two famous tamers of tigers

- Tiger in Chinese culture

- Tiger penis

- Tiger Temple, a Buddhist temple in Thailand famous for its tame tigers

Cited references

- ↑ Chundawat, R.S., Habib, B., Karanth, U., Kawanishi, K., Ahmad Khan, J., Lynam, T., Miquelle, D., Nyhus, P., Sunarto, Tilson, R. & Sonam Wang (2008). Panthera tigris. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 9 October 2008.

- ↑ "Wild Tiger Conservation". Save The Tiger Fund. http://www.savethetigerfund.org. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae:secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis.. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 41. http://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/726936. Retrieved 2008-09-08.

- ↑ "Encyclopaedia Britannica Online – Tiger (Panthera tigris)". http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9072439/tiger. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ↑ "Animal Face-Off: Lion vs. Tiger : Video : Animal Planet". Animal.discovery.com. 2008-04-29. http://animal.discovery.com/videos/animal-face-off-lion-vs-tiger.html. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ Cat Specialist Group.

- ↑ "BBC Wildfacts – Tiger". http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/wildfacts/factfiles/19.shtml.

- ↑ "Tiger Facts and Sound – Panthera tigris – Defenders of Wildlife – Defenders of Wildlife". Defenders.org. 2010-02-14. http://www.defenders.org/wildlife_and_habitat/wildlife/tiger.php. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "National Animal". Govt. of India Official website. http://india.gov.in/knowindia/national_animal.php.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George and Robert Scott (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ↑ "'Tiger' at the Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=tiger. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ (Latin) Linnaeus, C. (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata.. Holmiae. (Laurentii Salvii).. p. 824. http://dz1.gdz-cms.de/index.php?id=img&no_cache=1&IDDOC=265100.

- ↑ ""Panther"". Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper. http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=panther. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ ""Common Questions: What Do You Call a Group of...?">". http://www.npwrc.usgs.gov/about/faqs/animals/names.htm.

- ↑ Dinerstein, E., C. Loucks, E. Wikramanayake, J. Ginsberg, E. Sanderson, J. Forrest, G. Bryja, A. Heydlauff, S. Klenzendorf, P. Leimgruber, J. Mills. T. O’Brien, M. Shrestha, R. Simons, and M. Songer. 2007. The Fate of Wild Tigers. Bioscience 57(6):508–514.

- ↑ Dinerstein, E., C. Loucks, E. Wikramanayake, J. Ginsberg, E. Sanderson, J. Forrest, G. Bryja, A. Heydlauff, S. Klenzendorf, P. Leimgruber, J. Mills. T. O’Brien, M. Shrestha, R. Simons, and M. Songer. 2007. The Fate of Wild Tigers. Bioscience 57(6):508–514.

- ↑ Gubi, S. and A. Heydlauff. 2007. Tigers Forever. Oryx 41(1):13.

- ↑ Van den Hoek Ostende. 1999. Javan Tiger – Ruthlessly hunted down. 300 Pearls – Museum highlights of natural diversity. Downloaded on August 11, 2006.

- ↑ Piper et al. The first evidence for the past presence of the tiger Panthera tigris on the island of Palawan, Philippines: Extinction in an island population. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 264 (2008) 123–127

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 "WWF – Tigers – Ecology". http://www.worldwildlife.org/tigers/ecology.m.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 (German) Vratislav Mazak: Der Tiger. Nachdruck der 3. Auflage von 1983. Westarp Wissenschaften Hohenwarsleben, 2004 ISBN 3-89432-759-6

- ↑ Matthiessen, Peter. 2000. Tigers in the Snow, p. 47. The Harvill Press, London.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Matthiessen, Peter; Hornocker, Maurice (2001). Tigers In The Snow. North Point Press. ISBN 0865475962.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 V.G. Heptner & A.A. Sludskii. Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 2. ISBN 9004088768.

- ↑ Zoo animals. (2010). Retrieved from http://www.zooschool.ecsd.net/Tiger.htm

- ↑ EXPLORING MAMMALS, Marshall Cavendish, Marshall Cavendish Corporation, John L Gittleman

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Sunquist, Mel and Fiona Sunquist. 2002. Wild Cats of the World. University Of Chicago Press, Chicago

- ↑ "Task force says tigers under siege". Indianjungles.com. 2005-08-05. http://www.indianjungles.com/090805d.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ Wade, Matt (February 15, 2008). "Threat to a national symbol as India's wild tigers vanish". The Age (Melbourne): p. 9

- ↑ "No tigers found in Sariska: CBI". DeccanHerald.com. Archived from the original on 2007-02-10. http://web.archive.org/web/20070210220826/http://www.deccanherald.com/deccanherald/apr112005/national130442005410.asp. Retrieved 2007-07-20. (Archive).

- ↑ "Laboratory of Genomic Diversity LGD". http://home.ncifcrf.gov/ccr/lgd/.

- ↑ Cat Specialist Group (1996). Panthera tigris ssp. sumatrae. 2006. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 11 May 2006. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this subspecies is critically endangered and the criteria used.

- ↑ *Nowak, Ronald M. (1999) Walker's Mammals of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9

- ↑ Cracraft J., Feinstein J., Vaughn J., Helm-Bychowski K. (1998) Sorting out tigers (Panthera tigris) Mitochondrial sequences, nuclear inserts, systematics, and conservation genetics. Animal Conservation 1: 139–150.

- ↑ Kerley, L.L., J.M. Goodrich, D.G. Miquelle, E.N. Smirnov, H.G. Quigley, and M.G. Hornocker. 2003. Reproductive parameters of wild female Amur (Siberian) tigers (Panthera tigris altaica). Journal of Mammology 84:288–298.

- ↑ Graham Batemann: Die Tiere unserer Welt Raubtiere, Deutsche Ausgabe: Bertelsmann Verlag, 1986.

- ↑ "The Caspian Tiger – Panthera tigris virgata". http://www.tigerhomes.org/animal/curriculums/caspian-tiger-pc.cfm. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "The Caspian Tiger at www.lairweb.org.nz". http://www.lairweb.org.nz/tiger/caspian.html. Retrieved 12 October 2007.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Mitochondrial Phylogeography Illuminates the Origin of the Extinct Caspian Tiger and Its Relationship to the Amur Tiger". Plosone.org. http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0004125. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ www.china.org.cn Retrieved on 6 October 2007

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 "绝迹24年华南虎重现陕西 村民冒险拍下照片". News.xinhuanet.com. http://news.xinhuanet.com/newscenter/2007-10/13/content_6873252.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Rare China tiger seen in the wild". BBC News. 2007-10-12. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/asia-pacific/7042257.stm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "South China tiger photos are 'fake'". China Daily. 2007-11-17. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2007-11/17/content_6261263.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "South China tiger photos are fake: provincial authorities". China Daily date=2008-06-29. http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2008-06/29/content_6803353.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ Page, Jeremy (2008-06-30). "Farmer's photo of rare South China tiger is exposed as fake". London: The Times date=2008-06-30. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/asia/china/article4237441.ece. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Bambang M. 2002. In search of 'extinct' Javan tiger. The Jakarta Post (October 30)". Thejakartapost.com. http://www.thejakartapost.com/yesterdaydetail.asp?fileid=20021030.S03. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Harimau jawa belum punah! (Indonesian Javan Tiger website)". http://www.javantiger.or.id.

- ↑ "History of big cat hybridisation". http://www.lairweb.org.nz/tiger/hybridisation.html. Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- ↑ Guggisberg, C. A. W. (1975). Wild Cats of the World. New York: Taplinger Publishing. ISBN 0-8008-8324-1.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Markel, Scott; Darryl León (2003). Sequence Analysis in a Nutshell: a guide to common tools and databases. Sebastopol, California: O'Reily. ISBN 0-596-00494-X.

- ↑ "tigon – Encyclopædia Britannica Article". http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9001344/tigon. Retrieved 12 September 2007.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 "White tigers". http://www.lairweb.org.nz/tiger/white.html. Retrieved 25 September 2007.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "The white tiger today and the unusual white lion". Lairweb.org.nz. http://www.lairweb.org.nz/tiger/white.html. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "White Tigers". Bigcatrescue.org. http://www.bigcatrescue.org/cats/wild/white_tigers.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "White Tiger Facts". http://www.indiantiger.org/white-tigers/white-tiger-facts.html. Retrieved 26 September 2007.

- ↑ "White Tigers". Bigcathaven.org. http://bigcathaven.org/cats/wild/white_tigers_genetics.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "Snow Tigers". Bigcatrescue.org. http://www.bigcatrescue.org/cats/wild/snowtigers.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "Golden tabby Bengal tigers". Lairweb.org.nz. http://www.lairweb.org.nz/tiger/tabby.html. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ Mills, Stephen. (2004). Tiger. Pg. 89. BBC Books, London

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Mills, Stephen. pg. 86

- ↑ Thapar, Valmik. (1989). Tiger:Portrait of a Predator. pg. 88. Smithmark Pub, New York

- ↑ Thapar, Valmik. pg. 88

- ↑ Karanth, K.U., Nichols, J.D., Seidensticker, J., Dinerstein, E., Smith, J.L.D., McDougal, C., Johnsingh, A.J.T., Chundawat, R.S. (2003) Science deficiency in conservation practice: the monitoring of tiger populations in India. Animal Conservation (61): 141–146 Full text

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 64.3 Perry, Richard (1965). The World of the Tiger. p. 260. ASIN: B0007DU2IU.

- ↑ "Man-eaters. The tiger and lion, attacks on humans". Lairweb.org.nz. http://www.lairweb.org.nz/tiger/maneating7.html. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 ADW:Panthera tigris: Information, http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Panthera_tigris.html

- ↑ Tiger: Spy In The Jungle. John Downer Productions. BBC (2008)

- ↑ Schaller. G The Deer and the Tiger: A Study of Wildlife in India 1984, University Of Chicago Press

- ↑ Sankhala 1997, p. 17

- ↑ Sankhala 1997, p. 23

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Mills, Stephen (2004). Tiger. Richmond Hill., Ont.: Firefly Books. p. 168. ISBN 1552979490.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Thapar, Valmik. (1992). The Tiger's Destiny. Kyle Cathie Ltd: Publishers, London

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 73.3 Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9

- ↑ "Zoogoer – Tiger, Panthera tigris". http://nationalzoo.si.edu/Publications/ZooGoer/1998/2/tigerfacts.cfm. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ↑ "Tiger –". Bangalinet.com. http://www.bangalinet.com/tiger1.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Tiger – Oakland Zoo". Oaklandzoo.org. http://www.oaklandzoo.org/meet_the_animals/tiger. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ Sunquist, Fiona & Mel Sunquist. 1988. Tiger Moon. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- ↑ "Reptiles Database". jcvi.org. http://jcvi.org/reptiles/species.php?genus=Broghammerus&species=reticulatus. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ "Sympatric Tiger and Leopard: How two big cats coexist in the same area". http://www.ecology.info/tiger-leopard.htm. Ecology.info

- ↑ Karanth, K. Ullas; Sunquist, Melvin E. (2000). "Behavioural correlates of predation by tiger (Panthera tigris), leopard (Panthera pardus) and dhole (Cuon alpinus) in Nagarahole, India". Journal of Zoology 250: 255–265. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2000.tb01076.x. http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=40765. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ↑ "The IUCN-Reuters Media Awards 2000". IUCN. http://www.iucn.org/reuters/2000/eeurope.html. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ↑ "Amur Tiger". Save The Tiger Fund. http://www.savethetigerfund.org/Content/NavigationMenu2/Community/GeneralPublic/TigerSubspecies/AmurSiberianTigers/default.htm. Retrieved 2007-08-17.

- ↑ Perry, Richard (1965). The World of the Tiger. p. 260. ASIN B0007DU2IU.

- ↑ "Tiger". Big Cat Rescue. http://www.bigcatrescue.org/cats/wild/tiger.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ Cat Specialist Group (2002). Panthera Tigris. 2006. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2006. www.iucnredlist.org. Retrieved on 10 May 2006. Database entry includes justification for why this species is endangered.

- ↑ Tigress joins lone tiger in Sariska, Times of India, 4 July 2008.

- ↑ Students' Britannica India – By Dale Hoiberg, Indu Ramchandani. Books.google.com. 2000. ISBN 9780852297605. http://books.google.com/?id=DPP7O3nb3g0C&pg=PA153&dq=india+tiger+largest. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ Independent Online. "'World tiger population shrinking fast'". Iol.co.za. http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?sf=143&set_id=1&click_id=31&art_id=nw20080312141948377C153394. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ Dinerstein, E., Loucks, C., Heydlauff, A., Wikramanayake, E., Bryja, G., Forrest, J., Ginsberg, J., Klenzendorf, S., Leimgruber, P., O'Brien, T., Sanderson, E., Seidensticker, J., and Songer, M. Setting Priorities for the Conservation and Recovery of Wild Tigers: 2005–2015. A User's Guide. 1–50. 2006. Washington, D.C. – New York, WWF, WCS, Smithsonian, and NFWF-STF.

- ↑ Only 3500 tigers left worldwide – WWF

- ↑ "Front Page : Over half of tigers lost in 5 years: census". The Hindu. 2008-02-13. http://www.hindu.com/2008/02/13/stories/2008021357240100.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ Page, Jeremy (2008-07-05). "Tigers flown by helicopter to Sariska reserve to lift numbers in western India". The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/world/asia/article4272945.ece. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- ↑ "India Reports Sharp Decline in Wild Tigers". News.nationalgeographic.com. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2008/02/080213-AP-india-disap.html. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "It's the tale of a tiger, two tigresses in wilds of Sariska". Economictimes.indiatimes.com. 2009-03-02. http://economictimes.indiatimes.com/Earth/Its-the-tale-of-a-tiger-two-tigresses-in-wilds-of-Sariska/rssarticleshow/4212845.cms. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "Tigers galore in Ranthambhore National Park". Hindu.com. 2009-03-11. http://www.hindu.com/2009/03/11/stories/2009031152382000.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ Gubi, S. and A. Heydlauff. 2007. Tigers Forever. Oryx 41(1):13.

- ↑ Rabinowitz, A. 2009. Stop the bleeding: implementing a strategic Tiger Conservation Protocol. Cat News 51:30–31.

- ↑ J.M., D.G. Miquelle, E.M. Smirnov, L.L. Kerley, H.B. Quigley, and M.G. Hornocker. 2010. Spatial structure of Amur (Siberian) tigers (Panthera tigris altaica) on Sikhote-Alin Biosphere Zapovednik, Russia. Journal of Mammalogy, 91(3), 737–748.

- ↑ Wildlife Science: Linking Ecological Theory and Management Applications, By Timothy E. Fulbright, David G. Hewitt, Contributor Timothy E. Fulbright, David G. Hewitt, Published by CRC Press, 2007, ISBN 0-8493-7487-1

- ↑ Simon Denyer (March 6, 2006). "Dalai Lama offers Indian tigers a lifeline". iol.co.za. http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?set_id=1&click_id=143&art_id=qw1141631101585B251. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Justin Huggler (February 18, 2006). "Fur flies over tiger plight". New Zealand Herald. Tibet.com. http://www.tibet.com/NewsRoom/animalright2.htm. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ "Dalai Lama campaigns for wildlife". BBC News. April 6, 2005. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/4415929.stm. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ "Indian tiger isn't 100% “swadeshi (Made in India)”; by Pallava Bagla; Indian Express Newspaper; November 19, 1998". Indianexpress.com. 1998-11-19. http://www.indianexpress.com/res/web/pIe/ie/daily/19981119/32350524.html. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Tainted Royalty, Wildlife: Royal Bengal Tiger, a controversy arises over the purity of the Indian tiger after DNA samples show Siberian tiger genes. By Subhadra Menon. India Today, November 17, 1997". India-today.com. 1997-11-17. http://www.india-today.com/itoday/17111997/wild.html. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "The Tale of Tara, 4: Tara's Heritage from Tiger Territory website". Lairweb.org.nz. 1999-11-22. http://www.lairweb.org.nz/tiger/tara4.html. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Genetic pollution in wild Bengal tigers, Tiger Territory website". Lairweb.org.nz. http://www.lairweb.org.nz/tiger/bengal.html. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Interview with Billy Arjan Singh: Dudhwa's Tiger man, October 2000, Sanctuary Asia Magazine". Sanctuaryasia.com. 1917-08-15. http://www.sanctuaryasia.com/interviews/bilarjsingh.php. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Mitochondrial DNA sequence divergence among big cats and their hybrids by Pattabhiraman Shankaranarayanan* and Lalji Singh*, *Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Uppal Road, Hyderabad 500 007, India, Centre for DNA Fingerprinting and Diagnostics, CCMB Campus, Uppal Road, Hyderabad 500 007, India". Iisc.ernet.in. http://www.iisc.ernet.in/~currsci/nov10/articles18.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Central Zoo Authority of India (CZA), Government of India". CZA. http://www.cza.nic.in/research1.html. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ ""Indians Look At Their Big Cats' Genes", Science, Random Samples, Volume 278, Number 5339, Issue of 31 October 1997, 278: 807 (DOI: 10.1126/science.278.5339.807b) (in Random Samples),The American Association for the Advancement of Science". Sciencemag.org. http://www.sciencemag.org/content/vol278/issue5339/r-samples.dtl#278/5339/807b. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "BOOKS By & About Billy Arjan Singh". Fatheroflions.org. http://www.fatheroflions.org/ArjanSingh.html. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Book – Tara: The Cocktail Tigress/Ram Lakhan Singh. Edited by Rahul Karmakar. Allahabad, Print World, 2000, xxxviii, 108 p., ills., $22. ISBN 81-7738-000-1. A book criticizing Billy Arjan Singh's release of hand reared hybrid Tigress Tara in the wild at Dudhwa National Park in India". Vedamsbooks.com. https://www.vedamsbooks.com/no32235.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 "FAQs | Save China's Tigers". English.savechinastigers.org. 2004-07-25. http://english.savechinastigers.org/node/255. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ "FAQs | Save China's Tigers". English.savechinastigers.org. 2004-07-25. http://english.savechinastigers.org/node/255#14. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "The Baby Tiger That's Beating Extinction | Youtube Channel-SkyNews". Youtube.com. 2007-12-04. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iAnmxhTd1OA. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ James Pomfret. "Clock ticks for South China tigers in symbolic year | Reuters News". Connect-services.reuters.com. http://www.connect-services.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE61B12R20100212. Retrieved 2010-06-10.

- ↑ vide Royal Tiger (nom-de-plume) in The Manpoora Tiger – about a Tiger Hunt in Rajpootanah. (1836) Bengal Sporting Magazine, Vol IV. reproduced in The Treasures of Indian Wildlife

- ↑ "Man-eaters. The tiger and lion, attacks on humans". Lairweb.org.nz. http://www.lairweb.org.nz/tiger/maneating.html. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Man-eaters. The tiger and lion, attacks on humans". Lairweb.org.nz. http://www.lairweb.org.nz/tiger/maneating3.html. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Increasing tiger attacks trigger panic around Tadoba-Andhari reserve". Indianexpress.com. 2007-10-18. http://www.indianexpress.com/news/increasing-tiger-attacks-trigger-panic-around-tadobaandhari-reserve/229533/. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Climate change linked to Indian tiger attacks". http://www.enn.com/wildlife/article/38442. Retrieved 27 October 2008.

- ↑ Harding, Andrew (2006-09-23). "Programmes | From Our Own Correspondent | Beijing's penis emporium". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/programmes/from_our_own_correspondent/5371500.stm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Chinese tiger farms must be investigated". WWF. http://www.wwf.org.uk/news/n_0000003865.asp. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "WWF: Breeding tigers for trade soundly rejected at cites". Panda.org. http://www.panda.org/about_wwf/where_we_work/asia_pacific/where/bhutan/index.cfm?uNewsID=106740. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ Jackson, Patrick (29 January 2010). "Tigers and other farmyard animals". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/8487122.stm. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ http://www.bornfreeusa.org/b4a2_exotic_animals_summary.php

- ↑ Tamizhatamizha.com. (2009). Retrieved from http://tamizhatamizha.com/index.html

- ↑ "Tiger Culture | Save China's Tigers". English.savechinastigers.org. http://english.savechinastigers.org/node/316. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 129.2 129.3 Cooper, JC (1992). Symbolic and Mythological Animals. London: Aquarian Press. pp. 226–27. ISBN 1-85538-118-4.

- ↑ Balambal, V (1997). "19. Religion – Identity – Human Values – Indian Context". Bioethics in India: Proceedings of the International Bioethics Workshop in Madras: Biomanagement of Biogeoresources, 16–19 January 1997. Eubios Ethics Institute. http://www.eubios.info/india/BII19.HTM. Retrieved 2007-10-08.

- ↑ Summers, Montague (1966). The Werewolf. University Books. p. 21.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica. 1910–1911.

- ↑ National Animal Panthera tigris, Tiger is the national animal of India Govt. of India website,

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 134.2 Independent Online. "Tiger tops dog as world's favourite animal". Int.iol.co.za. http://www.int.iol.co.za/index.php?newslett=1&em=28164a99a20041206ah&click_id=29&art_id=qw1102325040750B216&set_id=1. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ Pers – The Tiger is the World's Favorite Animal

- ↑ "CBBC Newsround | Animals | Tiger 'is our favourite animal'". BBC News. 2004-12-06. http://news.bbc.co.uk/cbbcnews/hi/newsid_4070000/newsid_4073100/4073151.stm. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

- ↑ "Endangered tiger earns its stripes as the world's most popular beast | Independent, The (London) | Find Articles at BNET.com". Findarticles.com. 2004-12-06. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4158/is_20041206/ai_n12814678. Retrieved 2009-03-07.

References

- Brakefield, T. (1993). Big cats kingdom of might, Voyageur press.

- Dr. Tony Hare. (2001) Animal Habitats P. 172 ISBN 0-8160-4594-1

- Kothari, Ashok S. & Chhapgar, Boman F. (eds). 2005. The Treasures of Indian Wildlife. Bombay Natural History Society and Oxford University Press, Mumbai.

- Mazák, V. (1981). Panthera tigris. (PDF). Mammalian Species, 152: 1–8. American Society of Mammalogists.

- Nowak, Ronald M. (1999) Walker's Mammals of the World. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9

- Sankhala, K. (1997). Der indische Tiger und sein Reich. Bechtermuenz Verlag. ISBN 3-86047-734-X Abridged German translation of Return of the Tiger, Lustre Press, 1993.

- Seidensticker, John. (1999) Riding the Tiger. Tiger Conservation in Human-dominated Landscapes Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-64835-1

Tiger BANGKOK: Governments must act decisively to prevent the extinction of tigers in Southeast Asia's Greater Mekong region, where numbers have plunged more than 70 per cent in 12 years, the WWF said today.

The wild tiger population across Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, Thailand and Vietnam has dropped from an estimated 1,200 in 1998 — the last Year of the Tiger — to around 350 today, according to the conservation group.

The report was released ahead of a landmark three-day conference on tiger conservation, which will be attended in the Thai resort town of Hua Hin from tomorrow by ministers from 13 Asian tiger range countries.

It said the regional decline was reflected in the global wild tiger population, which is at an all-time low of 3,200, down from an estimated 20,000 in the 1980s and 100,000 a century ago.

"Today, wild tiger populations are at a crisis point," the WWF said, ahead of the start of the Year of the Tiger on Feb 14, according to the Chinese lunar calendar.

It cited growing demand for tiger body parts used in traditional Chinese medicine as a major factor endangering the region's Indochinese tiger population.

Infrastructure developments were also blamed by the report for fragmenting tigers' habitats, such as roads cutting through forests.

"Decisive action must be taken to ensure this iconic sub-species does not reach the point of no return," said Nick Cox, coordinator of the WWF Greater Mekong tiger programme.

"There is a potential for tiger populations in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia to become locally extinct by the next Year of the Tiger, in 2022, if we don't step up actions to protect them."

Although Indochinese tigers were once found in abundance across the Greater Mekong region, the WWF says there are now no more than 30 tigers per country in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.

The remaining populations are mainly found in mountainous border areas between Thailand and Myanmar. But the WWF is calling on the ministers in Hua Hin to take action to double the numbers of wild tigers by 2022.

"This region has huge potential to increase tiger numbers, but only if there are bold and coordinated efforts across the region and of an unprecedented scale that can protect existing tigers, tiger prey and their habitat," said Cox.

External links

- Truth about Tigers: Website with a lot of answers to the conservation issues faced by tigers

- 21st Century Tiger: information about tigers and conservation projects

- Biodiversity Heritage Library bibliography for Panthera tigris

- Save The Tiger Fund: Program of the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation

- Tiger Canyons Homepage: information about tigers and the Crossbred Tiger Rewilding project

- Tigers in Crisis: Information about Earth's Endangered Tigers

- WWF – Tigers

- Tiger Stamps: Tiger images on postage stamps from many different countries.

- Save China's Tigers: information about tigers and the South China Tiger rewilding project in Africa

- Sundarbans Tiger Project: research and conservation of tigers in the largest remaining mangrove forest in the world

- Explore T.I.G.E.R.S: The Institute of Greatly Endangered and Rare Species

- Tale of the Cat; Mar. 01, 2010; By Andrew Marshall; TIME Magazine (in partnership with CNN)

- BBC Year of the tiger: A video collection from the BBC highlighting the plight of the Tiger. Produced in celebration of the 2010 Year of the Tiger.

- Watch more tiger (Panthera tigris) video clips from the BBC archive on Wildlife Finder

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||