Temperature

Temperature is a physical property that underlies the common notions of hot and cold. Something that feels hotter generally has a higher temperature, though temperature is not a direct measurement of heat. Rather, temperature is the measure of the average kinetic energy of the particles in a substance, which is related to how hot or cold that substance is. Temperature is one of the principal parameters of thermodynamics. If no net heat flow occurs between two objects, the objects have the same temperature; otherwise, heat flows from the object with the higher temperature to the object with the lower one. This is a consequence of the laws of thermodynamics.

Historically, two equivalent scientific concepts of temperature have developed: the macroscopic thermodynamic description, and a microscopic explanation based on statistical physics. The thermodynamic definition of temperature, first stated by Lord Kelvin, is stated entirely in empirical, measurable variables, as could be measured with a thermometer. Statistical physics provides a deeper understanding by describing the atomic behavior of matter, and derives macroscopic properties from statistical averages of microscopic properties.

The statistical approach has shown that the thermodynamic definition of temperature can be interpreted as a measure of the average energy in each degree of freedom of the particles in the system. Because its temperature is seen as a statistical property, a system must contain a large number of particles for temperature to have a useful meaning. For a solid, this energy is found primarily in the vibrations of its atoms. In an ideal monatomic gas, energy is found in the translational motions of the particles; with molecular gases, vibrational and rotational motions also contribute.

Temperature is measured with thermometers that may be calibrated to a variety of temperature scales. In most of the world (except for Belize, Myanmar, Liberia and the United States), the Celsius scale is used for most temperature measuring purposes. The entire scientific world (these countries included) measures temperature using the Celsius scale and thermodynamic temperature using the Kelvin scale, which is just the Celsius scale shifted downwards so that 0 K[1]= −273.15 °C, or absolute zero. Many engineering fields in the U.S., notably high-tech and US federal specifications (civil and military), also use the Kelvin and Celsius scales. Other engineering fields in the U.S. also rely upon the Rankine scale (a shifted Fahrenheit scale) when working in thermodynamic-related disciplines such as combustion.

For a system in thermal equilibrium at a constant volume, temperature is thermodynamically defined in terms of its energy (E) and entropy (S) as:

Contents |

Overview

Scientifically, temperature is a measurement of the average kinetic energy of the particles in a substance. The most immediate way in which we can measure this is by feeling it. However, this is unreliable because it is based upon the phenomenon of felt air temperature, which can differ at varying degrees from actual temperature. On the molecular level, temperature is the result of the motion of particles which make up a substance. Temperature increases as the energy of this motion increases. The motion may be the translational motion of the particle, or the internal energy of the particle due to molecular vibration or the excitation of an electron energy level. Although very specialized laboratory equipment is required to directly detect the translational thermal motions, thermal collisions by atoms or molecules with small particles suspended in a fluid produces Brownian motion that can be seen with an ordinary microscope. The thermal motions of atoms are very fast and temperatures close to absolute zero are required to directly observe them. For instance, when scientists at the NIST achieved a record-setting low temperature of 700 nK (1 nK = 10−9 K) in 1994, they used optical lattice laser equipment to adiabatically cool caesium atoms. They then turned off the entrapment lasers and directly measured atom velocities of 7 mm per second in order to calculate their temperature.

Molecules, such as O2, have more degrees of freedom than single atoms: they can have rotational and vibrational motions as well as translational motion. An increase in temperature will cause the average translational energy to increase. It will also cause, through equipartition, the energy associated with vibrational and rotational modes to increase. Thus a diatomic gas, with extra degrees of freedom rotation and vibration, will require a higher energy input to change the temperature by a certain amount, i.e. it will have a higher heat capacity than a monatomic gas.

The process of cooling involves removing energy from a system. When there is no more energy able to be removed, the system is said to be at absolute zero, which is the point on the thermodynamic (absolute) temperature scale where all kinetic motion in the particles comprising matter ceases and they are at complete rest in the “classic” (non-quantum mechanical) sense. By definition, absolute zero is a temperature of precisely 0 kelvins (−273.15 °C or −459.68 °F).

Details

| Conjugate variables of thermodynamics |

|

|---|---|

| Pressure | Volume |

| (Stress) | (Strain) |

| Temperature | Entropy |

| Chemical potential | Particle number |

The formal properties of temperature follow from its mathematical definition (see below for the zeroth law definition and the second law definition) and are studied in thermodynamics and statistical mechanics.

Contrary to other thermodynamic quantities such as entropy and heat, whose microscopic definitions are valid even far away from thermodynamic equilibrium, temperature being an average energy per particle can only be defined at thermodynamic equilibrium, or at least local thermodynamic equilibrium (see below).

As a system receives heat, its temperature rises; similarly, a loss of heat from the system tends to decrease its temperature (at the—uncommon—exception of negative temperature; see below).

When two systems are at the same temperature, no heat transfer occurs between them. When a temperature difference does exist, heat will tend to move from the higher-temperature system to the lower-temperature system, until they are at thermal equilibrium. This heat transfer may occur via conduction, convection or radiation or combinations of them (see heat for additional discussion of the various mechanisms of heat transfer) and some ions may vary.

Temperature is also related to the amount of internal energy and enthalpy of a system: the higher the temperature of a system, the higher its internal energy and enthalpy.

Temperature is an intensive property of a system, meaning that it does not depend on the system size, the amount or type of material in the system, the same as for the pressure and density. By contrast, mass, volume, and entropy are extensive properties, and depend on the amount of material in the system.

Science

Temperature plays an important role in almost all fields of science, including physics, geology, chemistry, atmospheric sciences and biology.

Many physical properties of materials including the phase (solid, liquid, gaseous or plasma), density, solubility, vapor pressure, and electrical conductivity depend on the temperature. Temperature also plays an important role in determining the rate and extent to which chemical reactions occur. This is one reason why the human body has several elaborate mechanisms for maintaining the temperature at 310 K, since temperatures only a few degrees higher can result in harmful reactions with serious consequences. Temperature also controls the type and quantity of thermal radiation emitted from a surface. One application of this effect is the incandescent light bulb, in which a tungsten filament is electrically heated to a temperature at which significant quantities of visible light are emitted.

For study and analysis, the real world systems are usually spatially and temporally divided into 'cells' of small size, in which classical thermodynamical equilibrium conditions for matter are fulfilled to good approximation (local thermodynamic equilibrium).

Metrology

Temperature measurement using modern scientific thermometers and temperature scales goes back at least as far as the early 18th century, when Gabriel Fahrenheit adapted a thermometer (switching to mercury) and a scale both developed by Ole Christensen Rømer. Fahrenheit's scale is still in use in the United States for non-scientific applications.

Units

The basic unit of temperature (symbol: T) in the International System of Units (SI) is the kelvin (Symbol: K). The kelvin and Celsius scales are, by international agreement, defined by two points: absolute zero, and the triple point of Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water (water specially prepared with a specified blend of hydrogen and oxygen isotopes). Absolute zero is defined as being precisely 0 K and −273.15 °C. Absolute zero is where all kinetic motion in the particles comprising matter ceases and they are at complete rest in the “classic” (non-quantum mechanical) sense (the relationship between temperature and average kinetic energy is restricted to gases, therefore, it does not apply to temperatures near absolute zero. So zero temperature does not mean that everything is at rest. It means, rather, that all atoms and molecules are in the ground state)[2]. At absolute zero, matter contains no thermal energy. Also, the triple point of water is defined as being precisely 273.16 K and 0.01 °C. This definition does three things: 1) it fixes the magnitude of the kelvin unit as being precisely 1 part in 273.16 parts the difference between absolute zero and the triple point of water; 2) it establishes that one kelvin has precisely the same magnitude as a one degree increment on the Celsius scale; and 3) it establishes the difference between the two scales’ null points as being precisely 273.15 kelvins (0 K = −273.15 °C and 273.16 K = 0.01 °C). Formulas for converting from these defining units of temperature to other scales can be found at Temperature conversion formulas.

In the field of plasma physics, because of the high temperatures encountered and the electromagnetic nature of the phenomena involved, it is customary to express temperature in electronvolts (eV) or kiloelectronvolts (keV), where 1 eV = 11,605 K. In the study of QCD matter one routinely meets temperatures of the order of a few hundred MeV, equivalent to about 1012 K.

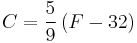

For everyday applications, it's very often convenient to use the Celsius scale, in which 0 °C corresponds to the temperature at which water freezes and 100 °C corresponds to the boiling point of water at sea level. Because liquid cloud droplets commonly exist in the atmosphere at sub-zero temperatures, 0 °C is better defined as the freezing point of bulk water or the melting point of ice. In this scale a temperature difference of 1 degree is the same as a 1 K temperature difference, so the scale is essentially the same as the Kelvin scale, but offset by the temperature at which water freezes (273.15 K). Thus the following equation can be used to convert from degrees Celsius to kelvins.

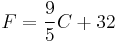

In the United States, the Fahrenheit scale is widely used. On this scale the freezing point of water corresponds to 32 °F and the boiling point to 212 °F. The following conversion formulas may be used to convert between Fahrenheit (F) and Celsius (C) temperature values:

and

and  .

.

See temperature conversion formulas for conversions between most temperature scales.

Negative temperature

In the macroscopic sense relevant to most people, a negative temperature is one below the zero-point of the measurement system used. For example, a temperature of 100 K is equivalent to −173.15 °C. Temperatures of macroscopic systems may have negative values in the Celsius and Fahrenheit, but not in the Kelvin or Rankine scales.

However, for some systems and specific definitions of temperature, it is possible to obtain a negative temperature, which is numerically less than absolute zero. However, a system with a negative temperature is not colder than absolute zero, but rather it is, in a sense, hotter than infinite temperature.[3] Negative temperature is "hotter" because, when brought into contact with a system at a positive temperature, energy will be transferred from the negative temperature system to the positive temperature system.

Theoretical foundation

Temperature in gases

For an ideal gas the kinetic theory of gases uses statistical mechanics to relate the temperature to the average kinetic energy of the atoms in the system. This average energy is independent of particle mass, which seems counter-intuitive. Temperature is related only to the average kinetic energy of the particles in a gas - each particle has its own energy which may or may not correspond to the average; the distribution of energies (and thus speeds) of the particles in any gas are given by the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. The temperature of a classical ideal gas is related to its average kinetic energy via the equation[4]:

, where

, where  (n= Avogadro number, R= ideal gas constant). This relation is valid in the classical regime, i.e. when the particle density is much less than

(n= Avogadro number, R= ideal gas constant). This relation is valid in the classical regime, i.e. when the particle density is much less than  , where

, where  is the thermal de Broglie wavelength.

is the thermal de Broglie wavelength.

In the case of a monoatomic gas, the kinetic energy is:

(Note that a calculation of the kinetic energy of a more complicated object, such as a molecule, is slightly more involved. Additional degrees of freedom are available, so molecular rotation or vibration must be included.)

The second law of thermodynamics states that any two given systems when interacting with each other will later reach the same average energy per particle (and hence the same temperature). In a mixture of particles of various mass, the heaviest particles will move more slowly than lighter counterparts, but will still have the same average energy. A neon atom moves slower relative to a hydrogen molecule of the same kinetic energy; a pollen particle moves in a slow Brownian motion among fast moving water molecules, etc. A visual illustration of this from Oklahoma State University makes the point more clear. Particles with different mass have different velocity distributions, but the average kinetic energy is the same because of the ideal gas law.

Temperature of vacuum

It is possible to use the zeroth law definition of temperature to assign a temperature to something not normally associated with temperatures, like a perfect vacuum. Because all objects emit black body radiation, a thermometer in a vacuum away from thermally radiating sources will radiate away its own thermal energy; decreasing in temperature indefinitely until it reaches the zero-point energy limit. At that point it can be said to be in equilibrium with the vacuum and by definition at the same temperature. A gas that behaved ideally all the way down to absolute zero, obeying the kinetic theory of gases, would achieve zero kinetic energy per particle, and thereby achieve absolute zero temperature. Thus, by the zeroth law a perfect, isolated vacuum is at absolute zero temperature. Note that in order to behave ideally in this context it is necessary for the atoms of the gas to have no zero point energy. It will turn out not to matter that this is not possible because the second law definition of temperature will yield the same result for any unique vacuum state.

More realistically, no such ideal vacuum exists. For instance a thermometer in a vacuum chamber which is maintained at some finite temperature (say, chamber is in the lab at room temperature) will equilibrate with the thermal radiation it receives from the chamber and with time reaches the temperature of the chamber. If a thermometer orbiting the Earth is exposed to sunlight, then it equilibrates at the temperature at which power received by the thermometer from the Sun is exactly equal to the power radiated away by thermal radiation of the thermometer. For a black body this equilibrium temperature is about 281 K (+8 °C). Since Earth has an albedo of 30%, average temperature as seen from space is lower than for a black body, 254 K, while the surface temperature is considerably higher due to the greenhouse effect.

A thermometer isolated from solar radiation (in the shade of the Earth, for example) is still exposed to thermal radiation of Earth - thus will show some equilibrium temperature at which it receives and radiates equal amount of energy. If this thermometer is close to Earth then its equilibrium temperature is about 236 K (-37 °C) provided that Earth surface is at 281 K.

A thermometer far away from the Solar system still receives Cosmic microwave background radiation. Equilibrium temperature of such thermometer is about 2.725 K, which is the temperature of a photon gas constituting black body microwave background radiation at present state of expansion of Universe. This temperature is sometimes referred to as the temperature of space. This temperature is thus similar to a test charge in that it facilitates a measure of the system even though temperature is not strictly defined there.

Definitions

Phenomenological definition based on second law of thermodynamics

In the previous section temperature was defined in terms of the Zeroth Law of thermodynamics. It is also possible to define temperature in terms of the second law of thermodynamics, which deals with entropy. Entropy is a measure of the disorder in a system. The second law states that any process will result in either no change or a net increase in the entropy of the universe. This can be understood in terms of probability. Consider a series of coin tosses. A perfectly ordered system would be one in which either every toss comes up heads or every toss comes up tails. This means that for a perfectly ordered set of coin tosses, there is only one set of toss outcomes possible: the set in which 100% of tosses came up the same.

On the other hand, there are multiple combinations that can result in disordered or mixed systems, where some fraction are heads and the rest tails. A disordered system can be 90% heads and 10% tails, or it could be 98% heads and 2% tails, et cetera. As the number of coin tosses increases, the number of possible combinations corresponding to imperfectly ordered systems increases. For a very large number of coin tosses, the combinations to ~50% heads and ~50% tails dominates and obtaining an outcome significantly different from 50/50 becomes extremely unlikely. Thus the system naturally progresses to a state of maximum disorder or entropy.

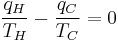

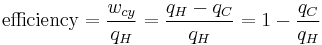

It has been previously stated that temperature controls the flow of heat between two systems and was just shown that the universe tends to progress so as to maximize entropy (this is expected of any natural system). Thus, it is expected that there is some relationship between temperature and entropy. To find this relationship, the relationship between heat, work and temperature is first considered. A heat engine is a device for converting heat into mechanical work and analysis of the Carnot heat engine provides the necessary relationships. The work from a heat engine corresponds to the difference between the heat put into the system at the high temperature, qH and the heat ejected at the low temperature, qC. The efficiency is the work divided by the heat put into the system or:

(2)

(2)

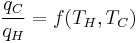

where wcy is the work done per cycle. The efficiency depends only on qC/qH. Because qC and qH correspond to heat transfer at the temperatures TC and TH, respectively, qC/qH should be some function of these temperatures:

(3)

(3)

Carnot's theorem states that all reversible engines operating between the same heat reservoirs are equally efficient. Thus, a heat engine operating between T1 and T3 must have the same efficiency as one consisting of two cycles, one between T1 and T2, and the second between T2 and T3. This can only be the case if:

Since the first function is independent of T2, this temperature must cancel on the right side, meaning f(T1,T3) is of the form g(T1)/g(T3) (i.e. f(T1,T3) = f(T1,T2)f(T2,T3) = g(T1)/g(T2)· g(T2)/g(T3) = g(T1)/g(T3)), where g is a function of a single temperature. A temperature scale can now be chosen with the property that:

(4)

(4)

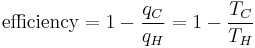

Substituting Equation 4 back into Equation 2 gives a relationship for the efficiency in terms of temperature:

(5)

(5)

Notice that for TC = 0 K the efficiency is 100% and that efficiency becomes greater than 100% below 0 K. Since an efficiency greater than 100% violates the first law of thermodynamics, this implies that 0 K is the minimum possible temperature. In fact the lowest temperature ever obtained in a macroscopic system was 20 nK, which was achieved in 1995 at NIST. Subtracting the right hand side of Equation 5 from the middle portion and rearranging gives:

where the negative sign indicates heat ejected from the system. This relationship suggests the existence of a state function, S, defined by:

(6)

(6)

where the subscript indicates a reversible process. The change of this state function around any cycle is zero, as is necessary for any state function. This function corresponds to the entropy of the system, which was described previously. Rearranging Equation 6 gives a new definition for temperature in terms of entropy and heat:

(7)

(7)

For a system, where entropy S may be a function S(E) of its energy E, the temperature T is given by:

(8)

(8)

i.e. the reciprocal of the temperature is the rate of increase of entropy with respect to energy.

Definition by statistical mechanics

The argument in the previous section is how the relation between entropy and heat was arrived at historically. Modern definition of temperature is given in Statistical mechanics and it is defined in terms of the fundamental degrees of freedom of a system (see the article on entropy for details). Eq.(8) of the previous section is then taken to be the defining relation of the temperature. Eq. (7) can be derived from the definition of entropy, see e.g. here.

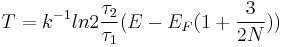

Generalized temperature from single particle statistics

It is possible to extend the definition of temperature even to systems made of few particles, like in a quantum dot. The generalized temperature is obtained by considering time ensembles instead of configuration space ensembles given in Statistical mechanics in the case of thermal and particle exchange between a small system of fermions (N even less than 10) with a single/double occupancy system. The finite quantum grand partition ensemble[5], obtained under the hypothesis of ergodicity and orthodicity, allows to express the generalized temperature from the ratio of the average time of occupation  1 and

1 and  2 of the single/double occupancy system [6]:

2 of the single/double occupancy system [6]:

where EF is the Fermi energy which tends to the ordinary temperature when N goes to infinity.

Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics

If two systems with fixed volumes are brought together in thermal contact, changes will most likely take place in the properties of both systems. These changes are caused by the transfer of heat between the systems. A state must be reached in which no further changes occur, to put the objects into thermal equilibrium.

A basis for the definition of temperature can therefore be obtained from the Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics which states that if two systems, A and B, are in thermal equilibrium and a third system C is in thermal equilibrium with system A then systems B and C will also be in thermal equilibrium (being in thermal equilibrium is a transitive relation; moreover, it is an equivalence relation). This is an empirical fact, based on observation rather than theory. Since A, B, and C are all in thermal equilibrium, it is reasonable to say each of these systems shares a common value of some property. This property is called temperature.

Generally, it is not convenient to place any two arbitrary systems in thermal contact to see if they are in thermal equilibrium and thus have the same temperature. Also, it would only provide an ordinal scale.

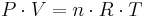

Therefore, it is useful to establish a temperature scale based on the properties of some reference system. Then, a measuring device can be calibrated based on the properties of the reference system and used to measure the temperature of other systems. One such reference system is a fixed quantity of gas. The ideal gas law indicates that the product of the pressure and volume (P · V) of a gas is directly proportional to the temperature[4]:

(1)

(1)

where 'T is temperature, n is the number of moles of gas and R is the gas constant. Thus, one can define a scale for temperature based on the corresponding pressure and volume of the gas: the temperature in kelvins is the pressure in pascals of one mole of gas in a container of one cubic metre, divided by 8.31... In practice, such a gas thermometer is not very convenient, but other measuring instruments can be calibrated to this scale.

The pressure, volume, and the number of moles of a substance are all inherently greater than or equal to zero, suggesting that temperature must also be greater than or equal to zero. As a practical matter it is not possible to use a gas thermometer to measure absolute zero temperature since the gasses tend to condense into a liquid long before the temperature reaches zero. It is possible to extrapolate how many degrees below the present temperature the absolute zero is from the temperature range where Equation 1 works.

| Effect of temperature | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Speed of sound | Density of air | Acoustic impedance |

in °C in °C |

c in m·s−1 | ρ in kg·m−3 | Z in N·s·m−3 |

| +35 | 351.96 | 1.1455 | 403.2 |

| +30 | 349.08 | 1.1644 | 406.5 |

| +25 | 346.18 | 1.1839 | 409.4 |

| +20 | 343.26 | 1.2041 | 413.3 |

| +15 | 340.31 | 1.2250 | 416.9 |

| +10 | 337.33 | 1.2466 | 420.5 |

| +5 | 334.33 | 1.2690 | 424.3 |

| ±0 | 331.30 | 1.2920 | 428.0 |

| -5 | 328.24 | 1.3163 | 432.1 |

| -10 | 325.16 | 1.3413 | 436.1 |

| -15 | 322.04 | 1.3673 | 440.3 |

| -20 | 318.89 | 1.3943 | 444.6 |

| -25 | 315.72 | 1.4224 | 449.1 |

Specific heat

Specific heat is the measure of the energy required to increase the temperature of a unit quantity of a substance by a unit of temperature. For example, the energy required to raise water’s temperature by one kelvin (equal to one degree Celsius) is 4186 J/kg.

See also

|

|

|

Notes

- ↑ This means "zero kelvins"; the unit kelvin is not used with a degree symbol because its name was changed from degrees Kelvin by the 13th CGPM in 1967–68; i.e. the notation 0 °K is not correct according to international standards

- ↑ http://www.calphad.com/absolute_zero.html

- ↑ Kittel and Kroemer, pp. 462

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Vu-Quoc, L., Configuration integral (statistical mechanics), 2008

- ↑ Prati, E. (2010). "The finite quantum grand canonical ensemble and temperature from single-electron statistics for a mesoscopic device". J. Stat. Mech. 1: P01003. http://www.iop.org/EJ/abstract/1742-5468/2010/01/P01003/. arxiv.org

- ↑ Prati, E., et al. (2010). "Measuring the temperature of a mesoscopic electron system by means of single electron statistics". Applied Physics Letters 96: 113109. doi:10.1063/1.3365204. http://link.aip.org/link/?APL/96/113109. arxiv.org

References

- Chang, Hasok (2004). Inventing Temperature: Measurement and Scientific Progress. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-517127-3.

- Kittel, Charles; Kroemer, Herbert (1980). Thermal Physics (2nd ed. ed.). W. H. Freeman Company. ISBN 0-7167-1088-9.

- Zemansky, Mark Waldo (1964). Temperatures Very Low and Very High. Princeton, N.J.: Van Nostrand.

External links

- An elementary introduction to temperature aimed at a middle school audience

- What is Temperature? An introductory discussion of temperature as a manifestation of kinetic theory.

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

![\mathrm{K = [^\circ C] \left(\frac{1 \, K}{1\, ^\circ C}\right) + 273.15\, K}](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/9912b6ce5daa2c92bc3d79557c739e43.png)