Nipple

| Nipple | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Human female nipple, areola and breast. | |

|

|

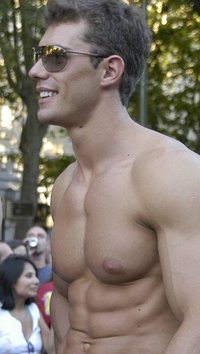

| Human male nipple.

Precursor = |

|

| Latin | papilla mammaria |

In its most general form, a nipple is a structure from which a fluid emanates. More specifically, it is the projection on the breasts or udder of a mammal by which breast milk is delivered to a mother's young. In this sense, it is often called a teat, especially when referring to non-humans. The rubber mouthpiece of a baby bottle or pacifier may also be referred to as a "nipple" or a "teat".

Contents |

Etymology

The word "teat" is of Germanic origin, having the same origin as the Dutch word "tiet" and German "Zitze". In turn, this word has Indo-European roots, as may be seen in the Welsh word "teth". The Old English for teat was "tit", which is still used as a vulgar or slang term for "breast" in Modern English.

Anatomy

In the anatomy of mammals, a nipple or mammary papilla or teat is a small projection of skin containing the outlets for 15-20 lactiferous ducts arranged cylindrically around the tip. The skin of the nipple is rich in a supply of special nerves that are sensitive to certain stimuli. The physiological purpose of nipples is to deliver milk to the infant, produced in the female mammary glands during lactation.

Marsupials and eutherian mammals typically have an even number of nipples arranged bilaterally, from as few as two to as many as 20.[1] They develop in the embryo, along the 'milk lines'. Most mammals develop multiple nipples along each milk line, with the total number approximating the maximum litter size, and half the total number (i.e. the number on one side) approximating the average litter size for that species. Monotremes, such as the platypus, lack teats; their young drink milk directly from pores in the skin (similar to sweat glands), or by sucking it off of hairs surrounding the pores.

In cetaceans such as whales, the infant cannot form a suction-seal to nurse, due to its mouth structure; the whale's nipple is therefore unlike that of any other mammal. Rather than requiring a sucking action, the discharge of milk is powered by maternal muscles. The calf takes the extended nipple into its mouth, and the mother ejects or expels her milk into the mouth of the calf.

Teats vary in size, location, and structure in different mammalian species. Teats, on occasion, become so plump and filled that milk may escape without suckling. Female goats and ewes have two teats, each with a single mammary gland, located between the hindlegs. Mares have two teats, each with two mammary glands. The teats of the sow can be quite variable in number, from six to thirty, and are located on two parallel lines along the belly. Cows have four teats, each with one mammary gland in the udder. Humans have two teats. Extra teats occur often, and are known as supernumerary teats. They are nonfunctional.

In most eutherian mammals, both males and females have teats. In the male, nipples are often not considered functional with regard to breastfeeding, although male lactation is possible. Notable exceptions to this are rats and horses, neither of which has teats in the male.

The pigments of the nipple and areola are brown eumelanin, a brown pigment, and to a greater extent pheomelanin, a red pigment. In many women, there are small bulges on the areola, which are called 'Montgomery bodies'. In humans, the nipple is innervated by the fourth intercostal nerve.

Instinct

Mammalian infants have a rooting instinct (moving their head so as to bring their mouth towards whatever is touching their face) for seeking the nipple, and a sucking instinct for extracting milk. The offspring of domestic animals, including piglets, calves, lambs, and foals, engage in a behavior known as teat seeking, sipping, and suckling. This strong instinct occurs in most species within minutes of birth, and serves both to connect the young to the food source and to encourage bonding between mother and young. The offspring thoroughly enjoy their suckling time, and may suckle even after filling up.

Nipples in humans

In infants

Most humans have two nipples after birth, located near the center of each breast and surrounded by an area of sensitive, pigmented skin known as the areola. Human fetuses develop several more nipples along the milk lines, which extend from the axilla (armpit), along the abdominal muscles, and down to the pubis (groin) on both sides. Those nipples usually disappear before birth, but sometimes remain, resulting in supernumerary nipples which uncommonly have lactiferous glands attached. Sometimes, babies, male or female, are born producing milk. This is common and is colloquially called 'witch's milk'. It is caused by maternal estrogens acting on the baby and disappears after several days.

Erection

The erection of nipples is not due to erectile tissue, but due to the contraction of smooth muscle under the control of the autonomic nervous system. It is more akin to a hair follicle standing on end than to a sexual erection. Nipple erections are a product of the pilomotor reflex which causes goose bumps. The erection of the nipple is partially due to the cylindrically-arranged muscle cells found within it.

Nipple erection can also be caused by a tactile response to cold temperature in both males and females. Nipple erection may also result during sexual arousal in females and males, or during breastfeeding. Both are caused by the release of oxytocin. The nipple and areola of males and females can be erotic receptors, sometimes intense enough to elicit orgasm in some individuals of either sex.

Changes in size

The average projection and size of human female nipples is slightly more than 3/8 of an inch (10mm).[2]. Pregnancy and nursing tend to increase nipple size, sometimes permanently. Pregnancy also deepens the pigmentation.

On male mammals

From conception until sexual differentiation, all mammalian fetuses within the same species look the same, regardless of sex. In humans this lasts for around 14 weeks, after which genetically-male fetuses begin producing male hormones such as testosterone. Usually, males' nipples do not change much past this point, however, some males develop a condition known as gynecomastia, in which the fatty tissue around and under the nipple develops into something similar to a female breast. This may happen whenever the testosterone level drops. Gynecomastia, although not as severe, may occur in pubescent boys undergoing physical changes due to the rapid and uncontrolled release of hormones, including estrogen. The heightened levels of estrogen in pubescent male bodies leads to the swelling of the nipple and surrounding tissue - this can often look similar to a female human nipple - and may cause slight discomfort.

Thus, because the "female template" is the default for humans, the question is not why evolution has not selected against male nipples, but why it would be advantageous to select against male nipples in the first place:

The uncoupling of male and female traits occurs if there is selection for it: if the trait is important to the reproductive success of both males and females but the best or "optimal" trait is different for a male and a female. We would not expect such an uncoupling if the attribute is important in both sexes and the "optimal" value is similar in both sexes, nor would we expect uncoupling to evolve if the attribute is important to one sex but unimportant in the other. The latter is the case for nipples. Their advantage in females, in terms of reproductive success, is clear. But because the genetic "default" is for males and females to share characters, the presence of nipples in males is probably best explained as a genetic correlation that persists through lack of selection against them, rather than selection for them. Interestingly, though, it could be argued that the occurrence of problems associated with the male nipple, such as carcinoma, constitutes contemporary selection against them. In a sense, male nipples are analogous to vestigial structures such as the remnants of useless pelvic bones in whales: if they did much harm, they would have disappeared.

In a now-famous paper, Stephen Jay Gould and Richard C. Lewontin emphasize that we should not immediately assume that every trait has an adaptive explanation. Just as the spandrels of St. Mark's domed cathedral in Venice are simply an architectural consequence of the meeting of a vaulted ceiling with its supporting pillars, the presence of nipples in male mammals is a genetic architectural by-product of nipples in females. So, why do men have nipples? Because females do.[3]

See also

- Areola

- Breast

- Breastfeeding

- Inverted nipple

- Lactation

- Mammary gland

- Milk

- Milk line

- Nipple piercing

- Oral stimulation of nipples

- Supernumerary (third) nipple

- Udder

References

- ↑ http://www.earthlife.net/mammals/milk.html

- ↑ M. Hussain, L. Rynn, C. Riordan and P. J. Regan, Nipple-areola reconstruction: outcome assessment; European Journal of Plastic Surgery, Vol. 26, Num. 7, December, 2003

- ↑ Simons, Andrew M. "Why do men have nipples? Scientific American (September 17, 2003)

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||