Bodhidharma

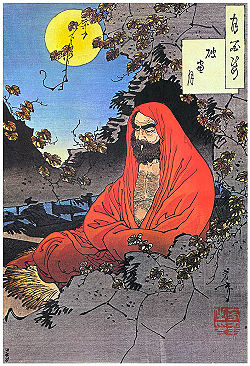

Bodhidharma, woodblock print by Yoshitoshi, 1887. |

|

| Names (details) | |

|---|---|

| Known in English as: | Bodhidharma |

| Tamil: | போதிதர்மன் |

| Sanskrit: | बोधिधर्म |

| Simplified Chinese: | 菩提达摩 |

| Traditional Chinese: | 菩提達摩 |

| Chinese abbreviation: | 達摩 |

| Hanyu Pinyin: | Pútídámó |

| Wade–Giles: | P'u-t'i-ta-mo |

| Tibetan: | Dharmottāra |

| Korean: | 달마 Dalma |

| Japanese: | 達磨 Daruma |

| Malay: | Dharuma |

| Thai: | ตั๊กม๊อ Takmor |

| Vietnamese: | Bồ-đề-đạt-ma |

Bodhidharma was a Buddhist monk who lived during the 5th/6th century and is traditionally credited as the transmitter of Zen (Chinese: Chán, Sanskrit: Dhyana) to China.

Little contemporary biographical information on Bodhidharma is extant, and subsequent accounts became layered with legend, but most accounts agree that he was from the southern region of India, born as a prince to a royal family. Bodhidharma left his kingdom after becoming a Buddhist monk and travelled through Southeast Asia into Southern China and subsequently relocated northwards. The accounts differ on the date of his arrival, with one early account claiming that he arrived during the Liú Sòng Dynasty (420–479) and later accounts dating his arrival to the Liáng Dynasty (502–557). Bodhidharma was primarily active in the lands of the Northern Wèi Dynasty (386–534). Modern scholarship dates him to about the early 5th century.[1]

Throughout Buddhist art, Bodhidharma is depicted as a rather ill-tempered, profusely bearded and wide-eyed barbarian. He is described as "The Blue-Eyed Barbarian" 藍眼睛的野人 (lán yǎnjīngde yěrén) in Chinese texts.[2]

The Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (952) identifies Bodhidharma as the 28th Patriarch of Buddhism in an uninterrupted line that extends all the way back to the Buddha himself. D.T. Suzuki contends that Chán's growth in popularity during the 7th and 8th centuries attracted criticism that it had "no authorized records of its direct transmission from the founder of Buddhism" and that Chán historians made Bodhidharma the 28th patriarch of Buddhism in response to such attacks.[3]

Contents |

Biography

|

Part of a series on Buddhism in China  |

|

|---|---|

| History | |

|

Timeline of Buddhism |

|

| Architecture | |

|

Chinese pagoda |

|

| Major Figures | |

|

Emperor Ming of Han |

|

| Chinese Buddhist Sects | |

| Chán • Tiantai • Huayan Pure Land • Weishi |

|

|

Practices and Attainment |

|

|

Buddhahood • Avalokiteśvara |

|

|

Festivals |

|

|

Buddha's Birthday |

|

| Texts | |

|

Chinese Buddhist canon |

|

| Sacred Mountains | |

|

Wutai • Emei • Jiuhua • Putuo |

|

| People Groups | |

|

Han • Manchu • Mongols |

|

| Culture | |

|

Buddhist Association of China |

|

|

|

|

Contemporary accounts

There are two known extant accounts written by contemporaries of Bodhidharma.

Yáng Xuànzhī

The Record of the Buddhist Monasteries of Luoyang (洛陽伽藍記 Luòyáng Qiélánjì), was compiled in 547 by his wife a writer and translator of Mahāyāna Buddhist texts into the Chinese language.

At that time there was a monk of the Western Region named Bodhidharma, a Persian Central Asian. He traveled from the wild borderlands to China. Seeing the golden disks [on the pole on top of Yung-ning's stupa] reflecting in the sun, the rays of light illuminating the surface of the clouds, the jewel-bells on the stupa blowing in the wind, the echoes reverberating beyond the heavens, he sang its praises. He exclaimed: "Truly this is the work of spirits." He said: "I am 150 years old, and I have passed through numerous countries. There is virtually no country I have not visited. Even the distant Buddha realms lack this." He chanted homage and placed his palms together in salutation for days on end.[4]

Broughton (1999:55) dates Bodhidharma's presence in Luoyang to between 516 and 526, when the temple referred to—Yǒngníngsì (永寧寺)—was at the height of its glory. Starting in 526, Yǒngníngsì suffered damage from a series of events, ultimately leading to its destruction in 534.[5]

Tánlín

The second account was written by Tánlín (曇林; 506–574). Tánlín's brief biography of the "Dharma Master" is found in his preface to the Two Entrances and Four Acts, a text traditionally attributed to Bodhidharma, and the first text to identify Bodhidharma as South Indian:

The Dharma Master was a South Indian of the Western Region. He was the third son of a great Indian king of the Pallava dynasty. His ambition lay in the Mahayana path, and so he put aside his white layman's robe for the black robe of a monk [...] Lamenting the decline of the true teaching in the outlands, he subsequently crossed distant mountains and seas, traveling about propagating the teaching in Han and Wei.[6]

Tánlín's account was the first to mention that Bodhidharma attracted disciples,[7] specifically mentioning Dàoyù (道育) and Huìkě (慧可), the latter of whom would later figure very prominently in the Bodhidharma literature.

Tánlín has traditionally been considered a disciple of Bodhidharma, but it is more likely that he was a student of Huìkě, who in turn was a student of Bodhidharma.[8]

Later accounts

Dàoxuān

In the 7th-century historical work Further Biographies of Eminent Monks (續高僧傳 Xù gāosēng zhuàn), Dàoxuān (道宣; 596-667) possibly drew on Tanlin's preface as a basic source, but made several significant additions:

Firstly, Dàoxuān adds more detail concerning Bodhidharma's origins, writing that he was of "South Indian Brahman stock" (南天竺婆羅門種 nán tiānzhú póluómén zhŏng).[9]

Secondly, more detail is provided concerning Bodhidharma's journeys. Tanlin's original is imprecise about Bodhidharma's travels, saying only that he "crossed distant mountains and seas" before arriving in Wei. Dàoxuān's account, however, implies "a specific itinerary":[10] "He first arrived at Nan-yüeh during the Sung period. From there he turned north and came to the Kingdom of Wei".[9] This implies that Bodhidharma had travelled to China by sea, and that he had crossed over the Yangtze River.

Thirdly, Dàoxuān suggests a date for Bodhidharma's arrival in China. He writes that Bodhidharma makes landfall in the time of the Song, thus making his arrival no later than the time of the Song's fall to the Southern Qi Dynasty in 479.[10]

Finally, Dàoxuān provides information concerning Bodhidharma's death. Bodhidharma, he writes, died at the banks of the Luo River, where he was interred by his disciple Huike, possibly in a cave. According to Dàoxuān's chronology, Bodhidharma's death must have occurred prior to 534, the date of the Northern Wei Dynasty's fall, because Huike subsequently leaves Luoyang for Ye. Furthermore, citing the shore of the Luo River as the place of death might possibly suggest that Bodhidharma died in the mass executions at Heyin in 528. Supporting this possibility is a report in the Taishō shinshū daizōkyō stating that a Buddhist monk was among the victims at Heyin.[11]

Epitaph for Fărú

The idea of a patriarchal lineage in Chán dates back to the epitaph for Fărú (法如 638–689), a disciple of the 5th patriarch Hóngrĕn (弘忍 601–674), which gives a line of descent identifying Bodhidharma as the first patriarch.[12]

Yǒngjiā Xuánjué

According to the Song of Enlightenment (證道歌 Zhèngdào gē) by Yǒngjiā Xuánjué (665-713)[13]—one of the chief disciples of Huìnéng, sixth Patriarch of Chán—Bodhidharma was the 28th Patriarch of Buddhism in a line of descent from Śākyamuni Buddha via his disciple Mahākāśyapa, and the first Patriarch of Chán:

Mahakashyapa was the first, leading the line of transmission;

Twenty-eight Fathers followed him in the West;

The Lamp was then brought over the sea to this country;

And Bodhidharma became the First Father here

His mantle, as we all know, passed over six Fathers,

And by them many minds came to see the Light.[14]

The idea of a line of descent from Śākyamuni Buddha is the basis for the distinctive lineage tradition of the Chán school.

Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall

In the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall (祖堂集 Zǔtángjí) of 952, the elements of the traditional Bodhidharma story are in place. Bodhidharma is said to have been a disciple of Prajñātāra,[15] thus establishing the latter as the 27th patriarch in India. After a three-year journey, Bodhidharma reaches China in 527[15] during the Liang Dynasty (as opposed to the Song period of the 5th century, as in Dàoxuān). The Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall includes Bodhidharma's encounter with Emperor Wu, which was first recorded around 758 in the appendix to a text by Shen-hui (神會), a disciple of Huineng.[16]

Finally, as opposed to Daoxuan's figure of "over 150 years,"[17] the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall states that Bodhidharma died at the age of 150. He was then buried on Mount Xiong'er (熊耳山 Xióngĕr Shān) to the west of Luoyang. However, three years after the burial, in the Pamir Mountains, Sòngyún (宋雲)—an official of one of the later Wei kingdoms—encountered Bodhidharma, who claimed to be returning to India and was carrying a single sandal. Bodhidharma predicted the death of Songyun's ruler, a prediction which was borne out upon the latter's return. Bodhidharma's tomb was then opened, and only a single sandal was found inside.

Insofar as, according to the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall, Bodhidharma left the Liang court in 527 and relocated to Mount Song near Luoyang and the Shaolin Monastery, where he "faced a wall for nine years, not speaking for the entire time",[18] his date of death can have been no earlier than 536. Moreover, his encounter with the Wei official indicates a date of death no later than 554, three years before the fall of the last Wei kingdom.

Dàoyuán

Subsequent to the Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall, the only dated addition to the biography of Bodhidharma is in the Jingde Records of the Transmission of the Lamp (景德傳燈錄 Jĭngdé chuándēng lù, published 1004 CE), by Dàoyuán (道原), in which it is stated that Bodhidharma's original name had been Bodhitāra but was changed by his master Prajñātāra.[19]

Modern scholarship

Bodhidharma's origins

Though Dàoxuān wrote that Bodhidharma was "of South Indian Brahman stock," Broughton (1999:2) notes that Bodhidharma's royal pedigree implies that he was of the Kshatriya warrior caste. Mahajan (1972:705–707) argued that the Pallava dynasty was a Tamilian dynasty and Zvelebil (1987) proposed that Bodhidharma was born a prince of the Pallava dynasty in their capital of Kanchipuram. Some other scholars have a view that Bodhidharma was a kalaripayattu master from the Malabar region .

Yáng Xuànzhī's eyewitness account identifies Bodhidharma as a Persian (波斯國胡人 bō-sī guó hú rén) from the Western Regions (西域 xī yù, usually referring to Central Asia), and Broughton (1999:54) notes that an Iranian Buddhist monk making his way to North China via the Silk Road is more likely than that of a South Indian master making his way by sea.[20] Broughton (1999:138) also states that the language Yang uses in his description of Bodhidharma is specifically associated with "Central Asia and particularly to peoples of Iranian extraction" and that of "an Iranian speaker who hailed from somewhere in Central Asia". However, Broughton 1999:54 notes that Yáng may have actually been referring to another monk named Boddhidharma, not related to the historical founder of Chan Buddhism.[21]

Bodhidharma's name

Bodhidharma was said to be originally named Bodhitara. His surname was Chadili. His Dhyāna teacher, Prajnatara, is said to have renamed him Bodhidharma.[22]

Faure (1986) notes that "Bodhidharma’s name appears sometimes truncated as Bodhi, or more often as Dharma (Ta-mo). In the first case, it may be confused with another of his rivals, Bodhiruci."

Tibetan sources give his name as "Bodhidharmottāra" or "Dharmottara", that is, "Highest teaching (dharma) of enlightenment".[23]

Practice and teaching

Meditation

Tanlin, in the preface to Two Entrances and Four Acts, and Daoxuan, in the Further Biographies of Eminent Monks, mention a practice of Bodhidharma's termed "wall-gazing" (壁觀 bìguān). Both Tanlin[24] and Daoxuan[25] associate this "wall-gazing" with "quieting [the] mind"[7] (安心 ān xīn). Elsewhere, Daoxuan also states: "The merits of Mahāyāna wall-gazing are the highest".[26] These are the first mentions in the historical record of what may be a type of meditation being ascribed to Bodhidharma.

In the Two Entrances and Four Acts, traditionally attributed to Bodhidharma, the term "wall-gazing" also appears:

Those who turn from delusion back to reality, who meditate on walls, the absence of self and other, the oneness of mortal and sage, and who remain unmoved even by scriptures are in complete and unspoken agreement with reason.[27]

Exactly what sort of practice Bodhidharma's "wall-gazing" was remains uncertain. Nearly all accounts have treated it either as an undefined variety of meditation, as Daoxuan and Dumoulin,[26] or as a variety of seated meditation akin to the zazen (坐禪; Chinese: zuòchán) that later became a defining characteristic of Chán; the latter interpretation is particularly common among those working from a Chán standpoint.[28] There have also, however, been interpretations of "wall-gazing" as a non-meditative phenomenon.[29]

The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra

The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, one of the Mahāyāna Buddhist sūtras, is a highly "difficult and obscure" text[30] whose basic thrust is to emphasize "the inner enlightenment that does away with all duality and is raised above all distinctions".[31] It is among the first and most important texts in the Yogācāra, or "Consciousness-only", school of Mahāyāna Buddhism.[32]

One of the recurrent emphases in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra is a lack of reliance on words to effectively express reality:

If, Mahamati, you say that because of the reality of words the objects are, this talk lacks in sense. Words are not known in all the Buddha-lands; words, Mahamati, are an artificial creation. In some Buddha-lands ideas are indicated by looking steadily, in others by gestures, in still others by a frown, by the movement of the eyes, by laughing, by yawning, or by the clearing of the throat, or by recollection, or by trembling.[33]

In contrast to the ineffectiveness of words, the sūtra instead stresses the importance of the "self-realization" that is "attained by noble wisdom"[34] and occurs "when one has an insight into reality as it is":[35] "The truth is the state of self-realization and is beyond categories of discrimination".[36] The sūtra goes on to outline the ultimate effects of an experience of self-realization:

[The Bodhisattva] will become thoroughly conversant with the noble truth of self-realization, will become a perfect master of his own mind, will conduct himself without effort, will be like a gem reflecting a variety of colours, will be able to assume the body of transformation, will be able to enter into the subtle minds of all beings, and, because of his firm belief in the truth of Mind-only, will, by gradually ascending the stages, become established in Buddhahood.[37]

One of the fundamental Chán texts attributed to Bodhidharma is a four-line stanza whose first two verses echo the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra's disdain for words and whose second two verses stress the importance of the insight into reality achieved through "self-realization":

A special transmission outside the scriptures,

Not founded upon words and letters;

By pointing directly to [one's] mind

It lets one see into [one's own true] nature and [thus] attain Buddhahood.[38]

The stanza, in fact, is not Bodhidharma's, but rather dates to the year 1108.[39] Nonetheless, there are earlier texts which explicitly associate Bodhidharma with the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra. Daoxuan, for example, in a late recension of his biography of Bodhidharma's successor Huike, has the sūtra as a basic and important element of the teachings passed down by Bodhidharma:

In the beginning Dhyana Master Bodhidharma took the four-roll Laṅkā Sūtra, handed it over to Huike, and said: "When I examine the land of China, it is clear that there is only this sutra. If you rely on it to practice, you will be able to cross over the world."[40]

Another early text, the Record of the Masters and Disciples of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra (楞伽師資記 Léngqié shīzī jì) of Jìngjué (淨覺; 683–750), also mentions Bodhidharma in relation to this text. Jingjue's account also makes explicit mention of "sitting meditation", or zazen:[41]

For all those who sat in meditation, Master Bodhi[dharma] also offered expositions of the main portions of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, which are collected in a volume of twelve or thirteen pages,[42] [...] bearing the title of Teaching of [Bodhi-]Dharma.[43]

In other early texts, the school that would later become known as Chán is sometimes referred to as the "Laṅkāvatāra school" (楞伽宗 Léngqié zōng).[44]

Legends

In Southeast Asia

According to Southeast Asian folklore, Bodhidharma travelled from south India by sea to Sumatra, Indonesia for the purpose of spreading the Mahayana doctrine. From Palembang, he went north into what are now Malaysia and Thailand. He travelled the region transmitting his knowledge of Buddhism and martial arts[45] before eventually entering China through Vietnam. Malay legend holds that Bodhidharma introduced preset forms to silat,[45] while Thais believe the techniques he brought to northern Siam formed the basis of Muay Thai.

Bodhidharma is also associated in legend with the Shaolin temple in China; see Bodhidharma at Shaolin for more.

Encounter with Emperor Liang

The Anthology of the Patriarchal Hall tells us that in 527 during the Liang Dynasty, Bodhidharma, the first Patriarch of Chán, visited the Emperor Wu, a fervent patron of Buddhism. The emperor asked Bodhidharma, "How much karmic merit have I earned for ordaining Buddhist monks, building monasteries, having sutras copied, and commissioning Buddha images?" Bodhidharma answered, "None, good deeds done with selfish intent bring no merit." The emperor then asked Bodhidharma, "So what is the highest meaning of noble truth?" Bodhidharma answered, "There is no noble truth, there is only void." The emperor then asked Bodhidharma, "Then, who is standing before me?" Bodhidharma answered, "I know not, Your Majesty."[46]

From then on, the emperor refused to listen to whatever Bodhidharma had to say. Although Bodhidharma came from India to China to become the first patriarch of China, the emperor refused to recognize him. Bodhidharma knew that he would face difficulty in the near future, but had the emperor been able to leave the throne and yield it to someone else, he could have avoided his fate of starving to death.

According to the teaching, Emperor Wu's past life was as a bhikshu. While he cultivated in the mountains, a monkey would always steal and eat the things he planted for food, as well as the fruit in the trees. One day, he was able to trap the monkey in a cave and blocked the entrance of the cave with rocks, hoping to teach the monkey a lesson. However, after two days, the bhikshu found that the monkey had died of starvation.

Supposedly, that monkey was reincarnated into Hou Jing of the Northern Wei Dynasty, who led his soldiers to attack Nanjing. After Nanjing was taken, the emperor was held in captivity in the palace and was not provided with any food, and was left to starve to death. Though Bodhidharma wanted to save him and brought forth a compassionate mind toward him, the emperor failed to recognize him, so there was nothing Bodhidharma could do. Thus, Bodhidharma had no choice but to leave Emperor Wu to die and went into meditation in a cave for nine years.

This encounter would later form the basis of the first kōan of the collection The Blue Cliff Record. However that version of the story is somewhat different. In the Blue Cliff's telling of the story, there is no claim that Emperor Wu did not listen to Bodhidharma after the Emperor was unable to grasp the meaning. Instead, Bodhidharma left the presence of the Emperor once Bodhidharma saw that the Emperor was unable to understand. Then Bodhidharma went across the river to the kingdom of Wei.

After Bodhidharma left, the Emperor asked the official in charge of the Imperial Annals about the encounter. The Official of the Annals then asked the Emperor if he still denied knowing who Bodhidharma was? When the Emperor said he didn't know, the Official said, "This was the Great-being Guanyin (i.e., the Mahasattva Avalokiteśvara) transmitting the imprint of the Buddha's Heart-Mind."

The Emperor regretted his having let Bodhidharma leave and was going to dispatch a messenger to go and beg Bodhidharma to return. The Official then said, "Your Highness, do not say to send out a messenger to go fetch him. The people of the entire nation could go, and he still would not return."

Nine years of wall-gazing

Failing to make a favorable impression in Southern China, Bodhidharma is said to have traveled to the northern Chinese kingdom of Wei to the Shaolin Monastery. After either being refused entry to the temple or being ejected after a short time, he lived in a nearby cave, where he "faced a wall for nine years, not speaking for the entire time".[18]

The biographical tradition is littered with apocryphal tales about Bodhidharma's life and circumstances. In one version of the story, he is said to have fallen asleep seven years into his nine years of wall-gazing. Becoming angry with himself, he cut off his eyelids to prevent it from happening again.[47] According to the legend, as his eyelids hit the floor the first tea plants sprang up; and thereafter tea would provide a stimulant to help keep students of Chán awake during meditation.[48]

The most popular account relates that Bodhidharma was admitted into the Shaolin temple after nine years in the cave and taught there for some time. However, other versions report that he "passed away, seated upright"[18]; or that he disappeared, leaving behind the Yi Jin Jing[49]; or that his legs atrophied after nine years of sitting,[50] which is why Japanese Bodhidharma dolls have no legs.

Bodhidharma at Shaolin

Some Chinese accounts describe Bodhidharma as being disturbed by the poor physical shape of the Shaolin monks, after which he instructed them in techniques to maintain their physical condition as well as teaching meditation. He is said to have taught a series of external exercises called the Eighteen Arhat Hands (Shi-ba Lohan Shou), and an internal practice called the Sinew Metamorphosis Classic.[51] In addition, after his departure from the temple, two manuscripts by Bodhidharma were said to be discovered inside the temple: the Yi Jin Jing or "Muscle/Tendon Change Classic" and the Xi Sui Jing. Copies and translations of the Yi Jin Jing survive to the modern day, though many modern historians believe it to be of much more recent origin.[49] The Xi Sui Jing has been lost.[22]

While Bodhidharma was born into the warrior caste in India and thus certainly studied and must have been proficient in self-defense, it is unlikely that he contributed to the development of self-defense technique specifically within China. However, the legend of his education of the monks at Shaolin in techniques for physical conditioning would imply (if true) a substantial contribution to Shaolin knowledge that contributed later to their renown for fighting skill. However, both the attribution of Shaolin boxing to Bodhidharma and the authenticity of the Yi Jin Jing itself have been discredited by some historians including Tang Hao, Xu Zhen and Matsuda Ryuchi. This argument is summarized by modern historian Lin Boyuan in his Zhongguo wushu shi as follows:

As for the "Yi Jin Jing" (Muscle Change Classic), a spurious text attributed to Bodhidharma and included in the legend of his transmitting martial arts at the temple, it was written in the Ming dynasty, in 1624, by the Daoist priest Zining of Mt. Tiantai, and falsely attributed to Bodhidharma. Forged prefaces, attributed to the Tang general Li Jing and the Southern Song general Niu Gao were written. They say that, after Bodhidharma faced the wall for nine years at Shaolin temple, he left behind an iron chest; when the monks opened this chest they found the two books "Xi Sui Jing" (Marrow Washing Classic) and "Yi Jin Jing" within. The first book was taken by his disciple Huike, and disappeared; as for the second, "the monks selfishly coveted it, practicing the skills therein, falling into heterodox ways, and losing the correct purpose of cultivating the Real. The Shaolin monks have made some fame for themselves through their fighting skill; this is all due to having obtained this manuscript." Based on this, Bodhidharma was claimed to be the ancestor of Shaolin martial arts. This manuscript is full of errors, absurdities and fantastic claims; it cannot be taken as a legitimate source.[49]

The oldest available copy was published in 1827[52] and the composition of the text itself has been dated to 1624.[49] Even then, the association of Bodhidharma with martial arts only becomes widespread as a result of the 1904–1907 serialization of the novel The Travels of Lao Ts'an in Illustrated Fiction Magazine.[53]

Teaching

In one legend, Bodhidharma refused to resume teaching until his would-be student, Dazu Huike, who had kept vigil for weeks in the deep snow outside of the monastery, cut off his own left arm to demonstrate sincerity.[54]

After death

Three years after Bodhidharma's death, Ambassador Songyun of northern Wei is said to have seen him walking while holding a shoe at the Pamir Heights. Songyun asked Bodhidharma where he was going, to which Bodhidharma replied "I am going home". When asked why he was holding his shoe, Bodhidharma answered "You will know when you reach Shaolin monastery". After arriving at Shaolin, the monks informed Songyun that Bodhidharma was dead and had been buried in a hill behind the temple. The grave was exhumed and was found to contain a single shoe. The monks then said "Master has gone back home" and prostrated three times.

For nine years he had remained and nobody knew him;

Carrying a shoe in hand he went home quietly, without ceremony.[55]

The lineage from Shakyamuni Buddha to Bodhidharma

- Shakyamuni Buddha

- 1.Mahakasyapa

- 2.Ananda

- 3.Sanavasa

- 4.Upagupta

- 5.Dhritaka

- 6.Michaka

- 7.Vasumitra

- 8.Buddhanandi

- 9.Buddhamitra

- 10.Parhsva

- 11.Punyayasas

- 12.Asvaghosa

- 13.Kapimala

- 14.Nagarjuna

- 15.Kanadeva

- 16.Rahulata

- 17.Sanghanandi

- 18.Sanghayasas

- 19.Kumarata

- 20.Jayata

- 21.Vasubandhu

- 22.Manura (Manorhita/Manorhata)

- 23.Haklenayasas

- 24.Aryasimha

- 25.Vasiasta (Vasi-Asita)

- 26.Punyamitra

- 27.Prajnatara

- 28.Bodhidharma

The lineage of Bodhidharma and his disciples

In the Two Entrances and Four Acts and the Continued Biographies of Eminent Monks, Daoyu and Huike are the only explicitly identified disciples of Bodhidharma. The Jingde Records of the Transmission of the Lamp gives Bodhidharma four disciples who, in increasing order of understanding, are Daofu, who attains Bodhidharma's skin; the nun Dharani,[57] who attains Bodhidharma's flesh; Daoyu, who attains Bodhidharma's bone; and Huike, who attains Bodhidharma's marrow.

Heng-Ching Shih [58] states that according to the Ching-te chuan-teng lu the first `bhiksuni` mentioned in the Ch'an literature was a disciple of the First Patriarch of Chinese Ch'an Bodhidharma, known as Tsung-chih [early-mid 500s]; Bodhidharma before returning to India after many years of teaching in China asked his disciples Tao-fu, Bhikshuni Tsung-chih, Tao-yu and Hui-k'o to relate their realization of the Dharma.[59] TSUNG-CH'IH is also known as Zongchi, by her title Soji, and by Myoren, her nun name. In the Shobogenzo chapter called Katto ("Twining Vines") by Dogen Zenji (1200–1253), she is named as one of Bodhidharma's four Dharma heirs. Although the First Patriarch's line continued through another of the four, Dogen emphasizes that each of them had a complete understanding of the teaching.[60]

- Bodhidharma

- Daoyu

- Yuan (Yuan-chi?)

- Tao-chih

- Huike

- Tanlin (506–574)

- Sengcan (d.606)

- Daoxin(580 - 651)

- Hongren(601 - 674)

- Huineng (638-713)

- Xuanjue (665-713)

- Huineng (638-713)

- Hongren(601 - 674)

- Daoxin(580 - 651)

- Layman Hsiang

- Hua-kung

- Yen-kung

- Dhyana Master Na

- Dhyana Master Ho

- Hsuan-ching

- Ching-ai

- T'an-yen

- Tao-an

- Tao-p'an

- Chih-tsang

- Seng-chao

- P'u-an

- Ch'ris Min-has

- Ching-yuan (1067–1120)[61]

Works attributed to Bodhidharma

- The Outline of Practice or Two Entrances

- The Bloodstream Sutra

- The Breakthrough Sutra

- The Wake-Up Sutra

See also

- Buddhism in China

- List of Buddhist topics

Notes

- ↑ Macmillan Encyclopedia of Buddhism (Volume One), pages 57, 130

- ↑ Soothill and Hodous

- ↑ Suzuki 1949:168

- ↑ Broughton 1999:54–55

- ↑ Broughton 1999:138

- ↑ Broughton 1999:8

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Broughton 1999:9

- ↑ Broughton 1999:53

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Dumoulin 2005:87

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Broughton 1999:56

- ↑ Broughton 1999:139

- ↑ Dumoulin 1993:37

- ↑ Chang, Chung-Yuan (1967), "Ch'an Buddhism: Logical and Illogical", Philosophy East and West (Philosophy East and West, Vol. 17, No. 1/4) 17 (1/4): 37–49, doi:10.2307/1397043, http://ccbs.ntu.edu.tw/FULLTEXT/JR-PHIL/ew27057.htm.

- ↑ Suzuki 1948:50

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Broughton 1999:2

- ↑ McRae, John R. (2000), "The Antecedents of Encounter Dialogue in Chinese Ch'an Buddhism", in Heine, Steven; Wright, Dale S., The Kōan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism, Oxford University Press, http://kr.buddhism.org/zen/koan/John_McRae.htm.

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005:88

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Lin 1996:182

- ↑ Broughton 1999:119

- ↑ Broughton 1999:54: "There is, however, nothing implausible about an early sixth-century Iranian Buddhist master who made his way to North China via the fabled Silk Road. This scenario is, in fact, more likely than a South Indian master who made his way by the sea route."

- ↑ Broughton 1999:54:

"Of course Yang may have been referring to another Bodhidharma. His record mentions a Bodhidharma twice in passing. This minor player's role is merely to illustrate that even a Westerner could be astonished by the imposing stupas and monasteries of metropolitan Lo-yang."

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Haines, Bruce (1995), "Chapter 3: China", Karate's history and traditions, Charles E. Tuttle Publishing Co., Inc, ISBN 0-8048-1947-5

- ↑ Tibetan Buddhism. By Steven D. Goodman, Ronald M. Davidson. SUNY Press, 1992. p. 65

- ↑ Broughton (1999:9, 66) translates 壁觀 as "wall-examining".

- ↑ Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō, Vol. 50, No. 2060, p. 551c 06(02)

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Dumoulin 2005:96

- ↑ Red Pine (1989:3), emphasis added.

Broughton (1999:9) offers a more literal rendering of the key phrase 凝住壁觀 (níngzhù bìguān) as "[who] in a coagulated state abides in wall-examining". - ↑ e.g., Keizan, Denkoroku;

Child, Simon, "In the Spirit of Chan". - ↑ viz. Broughton (1999:67–68), where a Tibetan Buddhist interpretation of "wall-gazing" as being akin to Dzogchen is offered.

- ↑ Suzuki 1932, Preface

- ↑ Kohn 1991:125

- ↑ Sutton 1991:1

- ↑ Suzuki 1932, XLII

- ↑ Suzuki 1932, XI(a)

- ↑ Suzuki 1932, XVI

- ↑ Suzuki 1932, IX

- ↑ Suzuki 1932, VIII

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005:85

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005:102

- ↑ Broughton 1999:62

- ↑ Taishō Shinshū Daizōkyō, Vol. 85, No. 2837, p. 1285b 17(05)

- ↑ The "volume" referred to is the Two Entrances and Four Acts.

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005:89

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005:52

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Zainal Abidin Shaikh Awab and Nigel Sutton (2006), Silat Tua: The Malay Dance Of Life, Kuala Lumpur: Azlan Ghanie Sdn Bhd, ISBN 9789834232801

- ↑ Broughton 1999:2–3

- ↑ Maguire 2001:58

- ↑ Watts, Alan W. (1962), The Way of Zen, Great Britain: Pelican books, pp. 106, ISBN 0140205470

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Lin 1996:183

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005:86

- ↑ Wong, Kiew Kit (2001), "Chapter 3: From Shaolin to Taijiquan", The Art of Shaolin Kungfu, Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 0-8048-3439-3

- ↑ Matsuda Ryuchi 松田隆智 (1986) (in Chinese), Zhōngguó wǔshù shǐlüè 中國武術史略, Taipei 臺北: Danqing tushu

- ↑ Henning, Stanley (1994), "Ignorance, Legend and Taijiquan", Journal of the Chenstyle Taijiquan Research Association of Hawaii 2 (3): 1–7, http://seinenkai.com/articles/henning/il&t.pdf.

- ↑ Maguire 2001:58

Dàoxuān records that Huìkě's arm was cut off by bandits (Broughton 1999:62). - ↑ Watts 1958:32

- ↑ Diener, Michael S. and friends.THE SHAMBHALA DICTIONARY OF BUDDHISM AND ZEN. 1991. Boston: Shambhala.page 266

- ↑ In the Jingde Records of the Transmission of the Lamp, Dharani repeats the words said by the nun Yuanji in the Two Entrances and Four Acts, possibly identifying the two with each other (Broughton 1999:132).

- ↑ see: Advisors - Ven. Bhiksuni Heng-ching Shih, Professor of Philosophy at Taiwan National University (Gelongma ordination 1975 in San Francisco).

- ↑ WOMEN IN ZEN BUDDHISM: Chinese Bhiksunis in the Ch'an Tradition by Heng-Ching Shih

- ↑ some information

- ↑ Zen Teachings of Fo-yen Ching-yuan

References

- Avari, Burjor (2007), India: The Ancient Past, New York: Routledge.

- Broughton, Jeffrey L. (1999), The Bodhidharma Anthology: The Earliest Records of Zen, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-21972-4

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005), Zen Buddhism: A History, 1: India and China, Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, ISBN 0-941532-89-5

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (1993), "Early Chinese Zen Reexamined: A Supplement to Zen Buddhism: A History", Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 20 (1): 31–53, ISSN 0304-1042, http://www.nanzan-u.ac.jp/SHUBUNKEN/publications/jjrs/pdf/387.pdf.

- Faure, Bernard (1986), "Bodhidharma as Textual and Religious Paradigm", History of Religions 25 (3): 187–198, doi:10.1086/463039, http://www.thezensite.com/ZenEssays/Philosophical/Bodhidharma_as_Paradigm.html

- Ferguson, Andrew. Zen's Chinese Heritage: The Masters and their Teachings. Somerville: Wisdom Publications, 2000. ISBN 0-86171-163-7.

- Hu, William; Bleicher, Fred (1965), "The Shadow of Bodhidharma", Black Belt Magazine (Black Belt Inc.) (May 1965, Vol. III, No. 5): 36–41, http://books.google.com/?id=z9kDAAAAMBAJ&lpg=PA41&dq=bodhidharma%20intitle%3Ablack%20intitle%3Abelt%20intitle%3Amagazine&pg=PA36#v=onepage&q=bodhidharma%20intitle:black%20intitle:belt%20intitle:magazine.

- Kohn, Michael H., ed. (1991), The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen, Boston: Shambhala.

- Lin, Boyuan (1996), Zhōngguó wǔshù shǐ 中國武術史, Taipei 臺北: Wǔzhōu chūbǎnshè 五洲出版社

- Maguire, Jack (2001), Essential Buddhism, New York: Pocket Books, ISBN 0-671-04188-6

- Mahajan, Vidya Dhar (1972), Ancient India, S. Chand & Co. OCLC 474621

- Red Pine, ed. (1989), The Zen Teaching of Bodhidharma: A Bilingual Edition, New York: North Point Press, ISBN 0-86547-399-4.

- Soothill, William Edward and Hodous, Lewis. A Dictionary of Chinese Buddhist Terms. London: RoutledgeCurzon, 1995.

- Sutton, Florin Giripescu (1991), Existence and Enlightenment in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra: A Study in the Ontology and Epistemology of the Yogācāra School of Mahāyāna Buddhism, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-0172-3.

- Suzuki, D.T., ed. (1932), The Lankavatara Sutra: A Mahayana Text, http://lirs.ru/do/lanka_eng/lanka-nondiacritical.htm.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1948), Manual of Zen Buddhism, http://consciouslivingfoundation.org/ebooks/new2/ManualOfZenBuddhism-manzen.pdf.

- Suzuki, D.T. (1949), Essays in Zen Buddhism, New York: Grove Press, ISBN 0-8021-5118-3

- Watts, Alan. The Way of Zen. New York: Vintage Books, 1985. ISBN 0-375-70510-4

- Watts, Alan (1958), The Spirit of Zen, New York: Grove Press.

- Williams, Paul. Mahayana Buddhism: The Doctrinal Foundations. ISBN 0-415-02537-0.

- Zvelebil, Kamil V. (1987), "The Sound of the One Hand", Journal of the American Oriental Society (Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 107, No. 1) 107 (1): 125–126, doi:10.2307/602960, http://jstor.org/stable/602960.

- 金实秋. Sino-Japanese-Korean Statue Dictionary of Bodhidharma (中日韩达摩造像图典). 宗教文化出版社, 2007-07. ISBN 7801238885

External links

- Essence of Mahayana Practice By Bodhidharma, with annotations. Also known as "The Outline of Practice." translated by Chung Tai Translation Committee

- Bodhidharma

- Bodhidharma

| Buddhist titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Prajñādhara |

Mahayana patriarch | Succeeded by Huike |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||