Tadeusz Kościuszko

| Tadeusz Kościuszko | |

|---|---|

| February 4, 1746 – October 15, 1817 (aged 71) | |

Portrait by Wojniakowski |

|

| Place of birth | Mereczowszczyzna, near Kosava, then in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, a part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, now in Belarus |

| Place of death | Solothurn, Switzerland |

| Years of service | 1765–1794 |

| Rank | U.S. Brigadier General by brevet, October 1783;[1] Generał dywizji |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War, Polish-Russian War of 1792, Kościuszko Uprising |

Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kościuszko ([taˈdɛuʂ kɔɕˈt͡ɕuʂkɔ] (![]() listen), Belarusian: Тадэвуш Касьцюшка, Lithuanian: Tadas Kosciuška; February 4, 1746 – October 15, 1817) was a Polish–Lithuanian[2][3] [4][5][6][7] general and military leader during the Kościuszko Uprising. He is a national hero in Poland, Lithuania,[8] the United States and Belarus.[9][10][11] He led the 1794 Kościuszko Uprising against Imperial Russia and the Kingdom of Prussia as Supreme Commander of the National Armed Force (Najwyższy Naczelnik Siły Zbrojnej Narodowej).[12]

listen), Belarusian: Тадэвуш Касьцюшка, Lithuanian: Tadas Kosciuška; February 4, 1746 – October 15, 1817) was a Polish–Lithuanian[2][3] [4][5][6][7] general and military leader during the Kościuszko Uprising. He is a national hero in Poland, Lithuania,[8] the United States and Belarus.[9][10][11] He led the 1794 Kościuszko Uprising against Imperial Russia and the Kingdom of Prussia as Supreme Commander of the National Armed Force (Najwyższy Naczelnik Siły Zbrojnej Narodowej).[12]

Before commanding the 1794 Uprising, he had fought in the American Revolutionary War as a colonel in the Continental Army. In 1783, in recognition of his dedicated service, he had been brevetted by the Continental Congress to the rank of brigadier general and had become a naturalized citizen of the United States.

There are several Anglicized spellings of Kościuszko's name. Perhaps the most frequently-occurring is Thaddeus Kosciusko, though the full "Andrew Thaddeus Bonaventure Kosciusko" is also seen. In Lithuanian, Kościuszko's name is rendered as Tadas Kosciuška[13] or Tadeušas Kosciuška. In Belarusian it is Tadevush Kasciushka.

Contents |

Early life

Kościuszko was born in the village of Mereczowszczyzna (Belarusian: Мерачоўшчына, Merachoushchyna), now abandoned, near the present-day town of Kosava, Belarus. The area lay within the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, a part of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[14]

Kościuszko was the son of a local noble Ludwik Tadeusz Kościuszko and Tekla, née Ratomska. He was the youngest child in a family whose lineages are traced partly to Lithuanian and Ruthenian nobility[15] and to a 15th–16th–century courtier of Polish King Sigismund I the Old, Konstanty Fiodorowicz Kostiuszko.[16][17][18] At the time of Tadeusz Kościuszko's birth, the family possessed modest holdings in the Grand Duchy.[15] His first language may have been Belarusian, and he was christened in both the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic religions.[19] As a result of the dual baptisms, he bore the names Andrei and Tadeusz.[19]

In 1765 Poland's King Stanisław August Poniatowski created at Warsaw, on the grounds of present-day Warsaw University, the Szkoła Rycerska (School of Knights) to educate military officers and government officials. Kościuszko enrolled on 18 December 1765, becoming a member of the Corps of Cadets. Since the school emphasized both military subjects and the liberal arts, his courses included world history, the history of Poland, philosophy, Latin, the Polish, German and French languages, and law, economics, geography, arithmetic, geometry and engineering. Upon graduation, he was promoted to captain.[14]

France

A civil war arose in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth during 1768, when the Bar Confederation sought to depose the king. Faced with the difficult choice between the rebels and his sponsors, the king and the Czartoryski family - who favored a more gradual approach to the problem of Russian domination - Kosciuszko chose to emigrate.[20] In 1769 Kościuszko and his colleague Orłowski were granted a royal scholarship and on October 5 they set off for Paris. While both sought to gain further military education, they were barred as foreigners from enrollment in any of the French military academies, and instead enrolled in the Royal Academy of Fine Arts and Sculpture.[20] For five years, however, Kościuszko educated himself as an extern, frequenting lectures and the libraries of the Paris military academies. His exposure to the Enlightenment there, coupled with the religious tolerance practiced in the Commonwealth, would have a strong influence on his later career.[21] The theory of Physiocracy made a particularly strong impression on his thinking.[20]

Return to Poland

By the First Partition of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in 1772, the adjoining countries of Russia, Prussia and Austria annexed large swaths of Polish-Lithuanian territory and acquired influence over the internal politics of the reduced Poland and Lithuania. The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was forced to cut back its Army to 10,000 men, and when Kościuszko finally returned home in 1774, there was no place for him in the Army. He took a position as tutor in the family of a provincial governor and fell in love with his pupil Ludwika Sosnowska. They eloped but were overtaken by her father's retainers.[15] Kościuszko received a thrashing at their hands — an event which may have led to his later antipathy to class distinctions.[15] In autumn of 1775 he decided to emigrate.

Dresden and Paris

In late 1775 Kościuszko arrived in Dresden, where he wanted to join either the Saxon court or the Elector's army. However, he was refused and decided to travel back to Paris. There he was informed of the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, in which the British colonies in North America had revolted against the crown and begun their struggle for independence. The first American successes were well publicized in France, and the revolutionaries' cause was openly supported by the French people and government.

American Revolution

Kościuszko came to Colonial America on his own,[22] and on August 30, 1776 he presented a Memorial to Congress. He initially served as a volunteer, but on October 18, 1776, Congress commissioned him a Colonel of Engineers in the Continental Army. "He was assigned a black orderly named Agrippa Hull. At the recommendation of Prince Adam Kazimierz Czartoryski and General Charles Lee, Kościuszko was named head engineer of the Continental Army.

He was sent to Pennsylvania to work with the Continental Army. Shortly after arriving, he read the United States Declaration of Independence. Kościuszko was moved by the document because it encompassed everything in which he believed; he was so moved, in fact, that he decided to meet Thomas Jefferson, the principal author of the Declaration. The two met in Virginia a few months later. After spending the day discussing philosophy and other things they shared in common, they became very close friends. Kościuszko was a guest at Monticello on many occasions, and spent prolonged visits there.

War in the north

Kościuszko's first task in America was the fortification of Philadelphia. His first structure was the construction of Fort Billingsport.[23] On September 24, 1776, Kościuszko was ordered to fortify the banks of the Delaware River against a possible British crossing. In the spring of 1777 he was attached to the Northern Army under Maj. Gen. Horatio Gates where he directed the construction of several forts and fortified military camps along the Canadian border.

Subsequently posted at Fort Ticonderoga, he worked to restore the defenses of what had once been one of the most formidable fortresses in North America. His surveys of the landscape prompted him to strongly recommend the construction of a battery on Sugar Loaf Mtn. overlooking the fort. Though a prudent suggestion, and one that carried the agreement of Kościuszko's fellow engineers, garrison commander Brigadier Gen. Arthur St. Clair ultimately declined to carry it out, citing logistical difficulties. This turned out to be an egregious tactical blunder, as, when the British Army under General John Burgoyne arrived in July, he did exactly what Kościuszko would have done and had his engineers place artillery on the hill.

With the British in complete control of the high ground, the Americans realized their situation was hopeless and abandoned the fortress with hardly a shot fired in the Siege of Ticonderoga. The British advance force nipped hard on the heels of the outnumbered and exhausted Continentals as they fled southward. Maj. Gen. Philip Schuyler, desperate to put distance between his men and their pursuers, ordered scorched earth tactics along the route of retreat. In his crucial rearguard role, Kościuszko carried out these orders by directing the felling of trees, damming of streams, and destruction of all bridges and causeways to deny the British use of the roadway. Encumbered by their vast supply train, the British slowly began to bog down, giving the Americans the time needed to safely withdraw across the Hudson River.

Shortly thereafter, General Gates relieved Schuyler, regrouping his forces to try and prevent the British from taking Albany. He tapped Kościuszko to survey the countryside between the opposing armies, choose the most defensible position he could, and fortify it. Finding just such a position near Saratoga, overlooking the Hudson at Bemis Heights, Kościuszko proceeded to lay out an excellent array of defenses; nearly impregnable to attack from any direction. His excellent judgment and meticulous attention to every detail in the American defense frustrated the British Army attack during the final battle on October 7, 1777. Added to the checking action at Freeman's Farm two weeks prior, the dwindling British army was dealt a sound tactical defeat, the combination turning the tide of the campaign to an American advantage.

The Americans were then free and able to pursue and bottle up the tattered remnants of the disintegrating British expedition. Having all but cut off the last means of escape, Gates accepted General Burgoyne's surrender of his entire force at Saratoga on October 16, 1777. This complete and total American victory marked the turning point of the entire war, leading directly to the alliance with France (concluded on February 6, 1778). Kościuszko's work at Saratoga received great praise from Gen. Gates, who later told his friend Dr. Benjamin Rush "...the great tacticians of the campaign were hills and forests, which a young Polish engineer was skillful enough to select for my encampment".

Thereafter, Kościuszko was regarded as one of the best engineers in American service. George Washington immediately took notice, tasking him with the command of improving defensive works at the stronghold in West Point. Here he was posted until being granted his request for transfer to the Southern Army in August of 1780. It was Kościuszko's defenses at West Point that General Benedict Arnold attempted to pass to the British when he turned traitor the following month. It was later revealed that the original blueprints had been destroyed before either Arnold or Gen. Washington could get their hands on them.

War in the south

Traveling southward through rural Virginia, where he witnessed chattel slavery for the first time up-close and personal, he eventually reported to his former commander Gen. Gates in North Carolina in October. However, following the disastrous defeat at the Battle of Camden on August 16, Congress selected Washington's choice of Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene to replace the disgraced Gates as commander of the Southern Department. When Gen. Greene formally assumed command on December 3, 1780, Kościuszko's services were retained, employed as Greene's chief engineer. In this capacity, he made substantial contributions towards the planning and execution of the general's overall strategy that culminated in the reconquest of the Carolinas and Georgia two years later.

Over the course of this campaign, he was placed in charge of constructing bateaux, siting camps, scouting river crossings, fortifying positions, and developing intelligence contacts. Many of his contributions were instrumental in preventing the destruction of the Southern Army. This was especially true during the famous "Race to the Dan", where Cornwallis and his exhausted troops chased Greene through 200 miles of rough backcountry terrain in the dead of winter. Thanks largely to a combination of Greene's tactics, and Kościuszko's bateaux and accurate scouting of the rivers ahead of the main body, the Continentals safely crossed each one in its path, including the Dan River. Cornwallis, having no boats of his own, and finding no way to cross the swollen Dan, finally gave up the chase and withdrew back into North Carolina, while the Continentals regrouped south of Halifax, VA, where Kościuszko had earlier established a fortified depot at Greene's request.

During the "Race to the Dan", Kościuszko had contributed to the selection of the site where Gen. Greene eventually returned to fight Cornwallis at Guilford Courthouse. Though tactically defeated, the Americans all but destroyed Cornwallis' army as an effective fighting force and gained a permanent strategic advantage in the South. Thus, as Greene began his reconquest of South Carolina in the spring of 1781, he recalled Kościuszko to rejoin the main body of the Southern Army. It wasn't long before he was back in his engineering element at Ninety Six where, from May 22 - June 18, he conducted the longest siege of the Revolutionary War. Kościuszko suffered his only wound in seven full years of service during the unsuccessful siege, as he was bayonetted in his hindquarters during an assault by the Star Fort's defenders on the approach trench he was preparing.

As the combined forces of the Continentals and Southern militia gradually forced the British from the backcountry into the coastal ports during the latter half of 1781, Kościuszko began participating in more direct action. There exists evidence he saw limited action in the major battles at Hobkirk's Hill (2nd Camden) in April and Eutaw Springs in September. However, he was most active throughout the final year of hostilities in much smaller actions focused on harassing British foraging parties near Charleston. His only known battlefield command of the war occurred at James Island on November 14, 1782. In what is believed by many to be the Continental Army's final armed action of the war, he was very nearly killed as his small force was soundly routed. A month later, he was among the first Continental troops to reoccupy Charleston following the British evacuation of the city. Kościuszko spent the rest of the war there, allegedly conducting a fireworks display to celebrate news of the signing of the Treaty of Paris in April, 1783.

Mustering-out

After seven years of faithful, uninterrupted service to the American cause, on October 13, 1783, Kościuszko was promoted by Congress to the rank of brigadier general. He also received American citizenship, a grant of land near present-day Columbus, Ohio, and was admitted to both the prestigious Society of the Cincinnati and the American Philosophical Society. When he was leaving America, he wrote a last will, naming Thomas Jefferson the executor and leaving his property in America to be used to buy the freedom of black slaves, including Jefferson's, and to educate them for independent life and work.[24] Several years after Kościuszko's death, Jefferson pled an inability to act as executor, an action deprecated by the abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison and Jefferson historian Merrill Peterson. The U.S. Supreme Court awarded the estate to Kościuszko's descendants in 1852,[25] ruling that he had died intestate despite the four wills he had made.[26] During the legal proceedings between the date of his death and the Supreme Court decision, the value of his estate decreased substantially; this was attributed by a case attorney to Colonel George Bomford's use of the estate for his own purposes.[26] None of the monies that Kościuszko had earmarked for the manumission and education of African-Americans were ever used for that purpose.[26]

Return to Poland

In July 1784 Kościuszko set off for Poland, where he arrived on August 12. He settled in his home village of Siechnowicze. The property, administered by his brother-in-law, brought a small but stable income, and Kościuszko decided to limit the servitude of his peasants (corvée) to two days a week, while completely exempting female serfs. This move was seen by local szlachta (nobility) as a sign of Kościuszko's dangerous liberalism.

By that time the internal situation in Poland was changing rapidly. A strong, if still informal, group of politicians advocated for reforms and for strengthening the state. Notable political writers such as Stanisław Staszic and Hugo Kołłątaj argued for granting the serfs and burghers more rights and for strengthening the central authorities. These ideas were supported by a large part of the szlachta, who also wanted to curb foreign meddling in Poland's internal affairs.

Finally the Great Sejm of 1788–92 opened the necessary reforms. One of its first acts was to approve the creation of a 100,000-man army to defend the Commonwealth's borders against its aggressive neighbors. Kościuszko saw this as a chance to return to military service and serve his country in the field that he knew best. He applied to the army and on October 12, 1789, received a royal commission as a major general. As such, he began receiving the high salary of 12,000 złotys a year, which ended his financial difficulties.

The Commonwealth's internal situation and the reforms initiated by the Constitution of May 3, 1791, the first constitution written in the modern era in Europe and second in the world after the American, were seen by the surrounding powers as a threat to their influence over Polish politics. On May 14, 1792, conservative magnates created the Targowica Confederation, which asked Russian Tsarina Catherine II for help in overthrowing the constitution. On May 18, 1792, a 100,000-man Russian army crossed the Polish border and headed for Warsaw, thus opening the Polish-Russian War of 1792.

Defense of the Constitution

Although the plan to create a 100,000-man Polish Army was not accomplished due to economic problems, the Polish Army was well-trained and prepared for war.

Before the Russians invaded Poland, Kościuszko was appointed deputy commander of Prince Józef Poniatowski's 3rd Crown Infantry Division. When the Prince became Commander in Chief of the entire Polish Army on May 3, 1792, Kościuszko automatically assumed command of the Division.

After Prussia's betrayal of her Polish ally, the Army of Lithuania did not oppose the advancing Russians. The Polish Army was too weak to oppose the enemy advancing into Ukraine and withdrew to the western side of the Bug River, where it regrouped and counterattacked. Victorious in the Battle of Zieleńce (June 18, 1792), Kościuszko was among the first to receive the newly-created Virtuti Militari medal, Poland's highest military decoration even today.

In the ensuing Battles of Włodzimierz (July 17, 1792, now Volodymyr-Volynskyi) and Dubienka (July 18) Kościuszko repulsed the numerically superior enemy and came to be regarded as one of Poland's most brilliant military commanders of the time. On August 1, 1792, King Stanisław August promoted him to Lieutenant General. But before the nomination arrived at Kościuszko's camp in Sieciechów, the King had joined the ranks of the Targowica Confederation and surrendered to the Russians.

Emigré: biding time

The King's capitulation was a hard blow for Kościuszko, who had not lost a single battle in the campaign. Together with many other notable Polish commanders and politicians he fled to Dresden and then to Leipzig, where the émigrées began preparing an uprising against Russian rule in Poland. The politicians, grouped around Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj, sought contacts with similar opposition groups formed in Poland and by spring 1793 had been joined by other politicians and revolutionaries, including Ignacy Działyński.

On August 26, 1792, the French Legislative Assembly awarded Kościuszko with honorary citizenship of France in honor of his fight for freedom of his fatherland and the ideas of equality and liberty. After two weeks in Leipzig, Kościuszko set off for Paris, where he tried to gain French support of the planned uprising in Poland.

On January 13, 1793, Prussia and Russia signed the Second Partition of Poland, which was ratified by the Sejm of Grodno on June 17. Such an outcome was a giant blow for the members of Targowica Confederation who saw their actions as a defense of centuries-old privileges of the magnates, but now were regarded by the majority of the Polish population as traitors. After the partition Poland became a small country of roughly 200,000 square kilometres and a population of approximately 4 million. The economy was ruined and the support for the cause of an uprising grew significantly, especially since there was no serious opposition to the idea after the Targowica Confederation was discredited.

In June of 1793 Kościuszko prepared a plan of an all-national uprising, mobilization of all the forces and a war against Russia. The preparations in Poland were slow and he decided to postpone the outbreak. However, the situation in Poland was changing rapidly. The Russian and Prussian governments forced Poland to again disband the majority of her armed forces and the reduced units were to be drafted to the Russian army. Also, in March the tsarist agents discovered the group of revolutionaries in Warsaw and started arresting notable Polish politicians and military commanders. Kościuszko was forced to execute his plan earlier than planned and on March 15, 1794 he set off for Kraków.

Kościuszko's Uprising

During the Uprising, Kościuszko was named Naczelnik (Commander-in-Chief) of all Polish-Lithuanian forces fighting against Russian occupation, and issued his Proclamation of Połaniec. After initial successes following the Battle of Racławice, Kościuszko was wounded at Maciejowice and captured by the Russians. He was imprisoned at Saint Petersburg in Prince Orlov's Marble Palace. Soon afterward, the uprising ended with the Siege of Warsaw.

Music

In 1777, Kościuszko composed a polonaise and scored it for the harpsichord. It was named after him, and became popular among Polish patriots at the time of the November Uprising in 1830-31, with lyrics written by Rajnold Suchodolski.[27]

Later life

In 1796 Tsar Paul I of Russia pardoned Kościuszko and set him free. In exchange for his oath of loyalty, Paul I also freed some 20,000 Polish political prisoners held in Russian prisons and forcibly settled in Siberia. The Tsar granted Kościuszko 12,000 roubles, which the Polish leader attempted in 1798 to return; the Tsar refused to accept it back as "money from a traitor".

Kościuszko emigrated to the United States, but the following year returned to Europe and in 1798 settled in Breville, near Paris. Still devoted to the Polish cause, he took part in creating the Polish Legions. Also, on October 17 and November 6, 1799 he met with Napoleon Bonaparte. However, he failed to reach any agreement with the French leader, who regarded Kościuszko as a "fool" who "overestimated his influence" in Poland (letter from Napoleon to Fouché, 1807).

Kościuszko remained politically active in Polish émigré circles in France and in 1799 was a founding member of the Society of Polish Republicans. However, he did not return to the Duchy of Warsaw and did not join the reborn Polish Army allied with Napoleon. Instead, after the fall of Napoleon's empire in 1815 he met with Russia's Tsar Alexander I in Braunau. In return for his prospective services, Kościuszko demanded social reforms and territorial gains for Poland, which he wished to reach as far as the Dvina and Dnieper Rivers in the east.

Alexander asked him to go to Warsaw. However, soon afterwards, in Vienna, Kościuszko learned that the Kingdom of Poland created by the Tsar would be even smaller than the earlier Duchy of Warsaw. Kościuszko called such an entity "a joke";[28] and when he received no reply to his letters to the Tsar, he left Vienna and moved to Solothurn, Switzerland, where his friend Franciszek Zeltner was mayor. Suffering from poor health and old wounds, on October 15, 1817 Kościuszko died there of typhoid fever.[29] Two years earlier, he had emancipated his serfs.

Kościuszko's body was embalmed and placed in a crypt at Solothurn's Jesuit Church. His viscera, removed in the process of embalming, were separately interred in a graveyard at Zuchwil, near Solothurn, except for the heart, for which an urn was fashioned. In 1818 Kościuszko's body was transferred to Kraków, Poland, and placed in a crypt at Wawel Cathedral, a pantheon of Polish kings and national heroes. Kościuszko's heart, which had been preserved at the Polish Museum in Rapperswil, Switzerland, was in 1927, along with the rest of the Museum's holdings, repatriated to Warsaw, where the heart now reposes in a chapel at the Royal Castle. Kościuszko's other viscera remain interred at Zuchwil, where a large memorial stone was erected in 1820 and can be visited today, next to a Polish memorial chapel.[30][31]

Commemorations

As a national hero in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, and the United States, Kościuszko has given his name to many places around the world and numerous monuments. The Polish explorer Count Paweł Edmund Strzelecki named the highest mountain in Australia, Mount Kosciuszko, after him. The mountain is the central feature of Kosciuszko National Park.

He has also given his name to Kosciusko, Mississippi and Kosciusko, Texas; Kosciusko County, Indiana; Kosciusko Island in Alaska; New York State's two Kosciuszko Bridges (in Latham on I-87 just north of Albany; and on the Brooklyn Queens Expressway); Kosciuszko Street (BMT Jamaica Line); the Kosciuszko Bridge that crosses the Naugatuck River in Naugatuck, Connecticut; Kosciuszko Street in Brooklyn, New York; Kosciuszko Street in Rochester, New York; Kosciuszko Street in Manchester, New Hampshire; Kosciuszko Street in Nanticoke, Pennsylvania; Kosciuszko Way in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Kosciuszko Park in Stamford, Connecticut; Kosciuszko Street in South Bend, Indiana, Kosciusko Street in Woburn, Massachusetts, General Thaddeus Kosciusko Way in downtown Los Angeles, California, Thaddeus Kosciuszko Memorial Highway as part of Route 9 in New Britain, Connecticut, General Thaddeus Kosciusko Memorial Highway as part of State Route 257 in Columbus, Ohio, and Kosciuszko Street in Bay City, Michigan.

Monmouth, Illinois, was to be called Kosciuszko after that name was drawn from a hat around 1831. It was decided that Kosciuszko would be too hard to pronounce, so Monmouth was selected as an alternative.

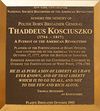

There is a Kościuszko Monument at the entrance to Kraków's Wawel Castle, where he was laid to rest.[33] Its replica was erected in Detroit, Michigan in 1978 (pictured). There is an equestrian statue of him at Kosciuszko Park in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, across from the Polish Basilica of St. Josaphat, and other statues, in Boston Public Garden; Scranton, Pennsylvania; Chicago's Museum Campus on Solidarity Drive; Lafayette Park in Washington, D.C.; the United States Military Academy at West Point; Williams Park in St. Petersburg, Florida; and Red Bud Springs Memorial Park in Kosciusko, Mississippi; in Kosciuszko Park in East Chicago, Indiana; and (with Kazimierz Pułaski) in Poland, Ohio, a village named in honor of the two heroes of the American Revolution.

In Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, his Revolutionary War home is preserved as Thaddeus Kosciuszko National Memorial, administered as part of Independence National Historical Park; and a monument to him stands at the corner of Benjamin Franklin Parkway and 18th Street. Hamtramck, Michigan, has a Kosciuszko Middle School; Winona, Minnesota has Washington-Kosciuszko Elementary School; Chicago, a public park named for him in Logan Square; and East Chicago, Indiana, a public park (with statue), a school and a neighborhood, all bearing Kosciuszko's name. Mount Pleasant, Pennsylvania has a Polish Falcons Sportsman's Club named after Kosciuszko. There is a Kosciusko Way in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In Grand Rapids, Michigan, there is a club called Kosciuszko Hall.

In Poland, every major town has a street or square named for Kościuszko. Between 1820 and 1823, the people of Kraków built the Kościuszko Mound (Polish: Kopiec Kościuszki) to commemorate the Polish leader. A similar mound was built in 1861 at Olkusz.

He is the patron of Kraków University of Technology, Wrocław Military University, and countless other schools and gymnasia (secondary schools) throughout Poland.

He was the patron of the 1st Regiment of the Polish 5th Rifle Division, and of the 1st Division of the Polish 1st Army. After World War I the Kościuszko Squadron, and during World War II the 303rd Polish Squadron, were named for him. Two ships have been named for him: SS Kościuszko, and ORP Generał Tadeusz Kościuszko (a former United States Navy frigate that was transferred to Poland).

There are also streets named for Kościuszko in Saint Petersburg, Russia; downtown Belgrade, Serbia (Ulica Tadeuša Košćuška); Budapest, Hungary (Kosciuszkó Tádé utca); and Vilnius, Lithuania (Kosciuškos gatvė). There is a Kosciusko Avenue in Geelong, Victoria and one in Canberra in Australia. A small street is named after him in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. A Kosciuszko monument in Minsk, Belarus was dedicated in 2005.[19]

Thomas Jefferson called Kościuszko "as pure a son of liberty as I have ever known."

Mikael Dziewanowski claims he was a "pioneer of emancipation and a spokesman for racial democracy and justice in eighteenth-century America."[34]

The home in Philadelphia, which is part of Independence National Historical Park, was actually his post-Revolutionary home. He lived there when he returned briefly to the USA.

The Kościuszko Polish Patriotic Social Society in Natrona, Pennsylvania is named after Kościuszko.

See also

- Kazimierz Pułaski (Anglicized as "Casimir Pulaski"), another Polish commander in the American Revolutionary War

- Kosciuszko Foundation

- List of Poles

Notes

- ↑ Alex Storozynski (2009). The Peasant Prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and the Age of Revolution. Macmillan. p. 114. ISBN 9780312388027. http://books.google.com/?id=l2eduXGh0FsC&pg=PT128&dq=kosciusko+brigadier+general+october+1783&q=.

- ↑ "Tadeusz Kościuszko". Encyclopedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/322659/Tadeusz-Kosciuszko. Retrieved 2009-11-08.

- ↑ Aušra Paulauskienė (2007). Lost and found: the discovery of Lithuania in American fiction. Rodopi. p. 23. ISBN 9789042022669. http://books.google.com/?id=rqtIbHwRRKkC&dq=A.+Paulauskiene+kosciusko+lost+and+found. "Both Kościuszko and Mickiewicz are known to have identified themselves as Lithuanian."

- ↑ Pamela Chester, Sibelan Elizabeth S. Forrester (1996). Engendering Slavic literatures. Indiana University Press. p. 57. ISBN 9780253210425. http://books.google.com/?id=KQD57bf5g0AC&pg=PA57&dq=Chester+Ko%C5%9Bciuszko#v=onepage&q=.

- ↑ R Morfill. The Story of Poland. 2009, p.239

- ↑ Aleksandra Piłsudska, Jennifer Ellis. Pilsudski. 1971, p.72

- ↑ Gordon McLachlan. Lithuania. 2008, p.20

- ↑ Belarusian review. Vol. 16-19, 2004 p.CX

- ↑ "?". http://www.belarus.by/en/about-belarus/famous-belarusians/tadeusz-kosciuszko.

- ↑ Радаводы Касцюшкаў // Анатоль Бензярук. Касцюшкі-Сяхновіцкія. Гісторыя старадаўняга роду. — Брэст: Издательство «Академия», 2006. — 132 с.

- ↑ Тадэвуш Касцюшка — ганаровы грамадзянін Францыі, нацыянальны герой ЗША, Польшчы і Беларусі // Звязда. — 1994. — 23 сак.

- ↑ Bartłomiej Szyndler, Powstanie kościuszkowskie 1794, Warszawa 1994, passim.

- ↑ Alfredas Bumblauskas. "Lithuania’s Millennium – Millennium Lithuaniae, Or what Lithuania can tell the world on this occasion". http://www.lietuviai.se/uploads/file/Straipsniai/A_Bumblauskas_english_RED.pdf. Retrieved 2010-01-20.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Tadeusz Kosciuszko: A man of unwavering principle". The Institute of World Politics. http://www.iwp.edu/about/pageID.245/default.asp. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Lituanus 32 (No. 1 - Spring 1986). http://www.lituanus.org/1986/86_1_03.htm. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ↑ Tadeusz Korzon, Kościuszko, biografia z dokumentów wysnuta. Kraków, Warszawa, 1894.

- ↑ "?". http://www.belarus-misc.org/kosciusko.htm.

- ↑ "?". http://www.belarusguide.com/cities/commanders/Kasciushka_&_others.html.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 George A. Krol. "Tadeusz Kosciuszko Monument Unveiled in Minsk". Belarusan-American Association, Inc.. http://www.belreview.cz/articles/2932.html. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Alex Storozynski (2009). The peasant prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and the age of revolution. Macmillan. pp. 9–12. ISBN 9780312388027. http://books.google.com/?id=qAzjgfuBufUC&pg=PA9&dq=Ko%C5%9Bciuszko+lithuanian-ruthenian&cd=2#v=onepage&q=.

- ↑ "Comprehensive Plan - Liberty in My Name". National Park Service. http://www.nps.gov/thko/upload/KHouse%20REV%20CompPlan.pdf. Retrieved 2009-07-03.

- ↑ Martin I.J. Griffin (2006-06). Catholics and the American Revolution. p. 133. ISBN 9781428628434. http://books.google.com/?id=-OdphE7yhXwC&pg=PA133&lpg=PA133&dq=deane+kosciusko.

- ↑ Colimore, Edward (December 10, 2007). "Fighting to save remains of a fort". Philadelphia Inquirer. http://www.philly.com/inquirer/home_region/20071210_Fighting_to_save_remains_of_a_fort.html.

- ↑ Kościuszko's American last will and testament, in English translation in Manfred Kridl, ed., For Your Freedom and Ours.

- ↑ Gary B. Nash and Graham Russell Gao Hodges. "Why We Should All Regret Jefferson's Broken Promise to Kościuszko". History News Network. http://hnn.us/articles/48794.html. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Alex Storozynski (2009). The Peasant Prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and the Age of Revolution. Macmillan. p. 282. ISBN 9780312388027. http://books.google.com/?id=l2eduXGh0FsC&pg=PT128&dq=kosciusko+brigadier+general+october+1783&q=.

- ↑ Margaret Anderton, "The Spirit of the Polonaise," Polish Music Journal Vol. 5, No. 2, Winter 2002.

- ↑ Feliks Koneczny - "Święci w dziejach Narodu Polskiego".

- ↑ For your freedom and ours, the Kościuszko squadron, Olson&Cloud, pg 22, Arrow books ISBN 0-09-942812-1

- ↑ Gemeinde Zuchwil (German)

- ↑ Kościuszko Mound: Biography

- ↑ Zacharias, Pat, The Monuments of Detroit, September 5, 1999. Detroit News

- ↑ Rick Steves, Cameron Hewitt, Rick Steves' Best of Eastern Europe 2007 by Avalon

- ↑ Mikael Dziewanowski's "Tadeuz Kościuszko, Kazimierz Puaski, and the American War of Independence," in Jaraslaw Pelenki, ed., The American and European Revolutions, 1776-1848: Sociopolitical and Ideological Aspects; Proceedings of the Second Bicentennial Conference of Polish and American Historians, September 29 — October 1, 1976 (Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 1980).

References

- Pula, James S. (1998). Thaddeus Kosciuszko: The Purest Son of Liberty. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 0781805767.

- Niestsiarchuk, Leanid (2006) (in Belarusian). Андрэй Тадэвуш Банавентура Касцюшка: Вяртаннегероя нарадзіму (Andrzej Tadeusz Bonawentura Kosciuszko: Return of the Hero to his Motherland). ISBN 9856665930.

- Nash, Gary B.; Graham Russell Gao Hodges (2008). Friends of Liberty: Thomas Jefferson, Thaddeus Kosciuszko, and Agrippa Hull. Basic Books. ISBN 9780465048144.

- Storozynski, Alex (2009). The Peasant Prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and The Age of Revolution, Thomas Dunne Books, ISBN 978-0-312-38802-7, ISBN 0-312-38802-0

- Manfred Kridl, ed., For Your Freedom and Ours.

External links

- The Peasant Prince (Unknown story of Kosciuszko’s life, liberty and pursuit of tolerance during the age of revolution)Storozynski, Alex (2009). The Peasant Prince: Thaddeus Kosciuszko and The Age of Revolution, Thomas Dunne Books, ISBN 978-0-312-38802-7, ISBN 0-312-38802-0

- Thaddeus Kosciuszko as an Artist (book about the Polish-American hero.)

- Kosciuszko by Monica Mary Gardner

- The Kosciuszko Foundation. (Polish-American cultural foundation named for General Tadeusz Kosciuszko.)

- Mt. Kosciuszko Inc. Webpage of Australia's Mt. Kosciuszko Association (named for Australia's highest mountain peak).

- About.com feature on Tadeusz Kosciuszko.

- Polish Embassy in the United States: a tribute page.

- US Kosciuszko National Monument web site.

- Kosciuszko Polish-American Historical Society, Inc., of the Valley Ansonia - Derby - Shelton - Seymour, Connecticut.

- Kosciuszko monuments gallery.

- Tadeusz Kościuszko at Find-a-grave.

- Unknown Kościuszko manuscript (Nieznany rękopis Tadeusza Kościuszki).

- Photographs of Mereszowszczyzna manor in Belarus.

- A humorous biographical comic about Kościuszko.

- Will of Thaddeus Kosciuszko.

- Henri La Fayette Villaume Ducoudray Holstein (1833). Le Glaneur Francais, Number One. pp. 251–252. http://books.google.com/?id=SDABAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA240&dq=maubourg.