Outer Hebrides

| Outer Hebrides | |

|---|---|

| Location | |

| OS grid reference | NB426340 |

| Names | |

| Gaelic name | Na h-Eileanan Siar |

| Meaning of name | Western Isles |

| Area and summit | |

| Area | 3,070 km2 (1,190 sq mi)[1] |

| Highest elevation | Clisham 799 m (2,621 ft)[2] |

| Population | |

| Population | 26,502[3] |

| Main settlement | Stornoway |

| Groupings | |

| Local Authority | Comhairle nan Eilean Siar |

| If shown, area and population ranks are for all Scottish islands and all inhabited Scottish islands respectively. Population data is from 2001 census. | |

The Outer Hebrides (Scottish Gaelic: Na h-Eileanan Siar, IPA: [nə ˈhelanən ˈʃiəɾ]) also known as the Western Isles and the Long Island, is an island chain off the west coast of Scotland. The islands are geographically contiguous with Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, one of the 32 unitary council areas of Scotland. They form part of the Hebrides, separated from the Scottish mainland and from the Inner Hebrides by the waters of the Minch, the Little Minch and the Sea of the Hebrides. Scottish Gaelic was formerly the dominant language and remains widely spoken, although in some areas English speakers form a majority.

Most of the islands have a bedrock formed from ancient metamorphic rocks and the climate is mild and oceanic. The 15 inhabited islands have a total population of about 26,500 and there are more than fifty substantial uninhabited islands.

There are a number of important prehistoric structures, many of which pre-date the first written references to the islands by Roman and Greek authors. The Western Isles became part of the Suðreyjar kingdom of the Norse, who ruled for over 400 years until sovereignty was transferred to Scotland by the Treaty of Perth in 1266. Control of the islands was then held by clan chiefs, principle of whom were the MacLeods, MacDonalds, Mackenzies and MacNeils. The Highland Clearances of the 19th century had a devastating effect on many communities and it is only in recent years that population levels have ceased to decline. Much of the land is now under local control and commercial activity is based on tourism, crofting, fishing, and weaving.

Sea transport is crucial and a variety of ferry services operate between the islands and to mainland Britain. Modern navigation systems now minimise the dangers but in the past the stormy seas have claimed many ships. Religion, music and sport are important aspects of local culture, and there are numerous designated conservation areas to protect the natural environment.

Contents |

Geography

The main islands form an archipelago of which the major islands include Lewis and Harris, North Uist, Benbecula, South Uist, and Barra. Lewis and Harris has an area of 217,898 hectares (841 sq mi)[4] and is the largest island in Scotland and the third largest in the British Isles, after Great Britain and Ireland.[5] It incorporates Lewis in the north and Harris in the south, both of which are frequently referred to as individual islands, although they are joined by a land border.[Note 1]

Much of the western coastline of the islands is machair, a fertile low-lying dune pastureland.[7] Lewis is comparatively flat, and largely consists of treeless moors of blanket peat. The highest eminence is Mealisval at 574 m (1,883 ft) in the south west. Most of Harris is mountainous, with large areas of exposed rock and Clisham, the archipelago's only Corbett, reaches 799 m (2,621 ft) in height.[2][4] North and South Uist and Benbecula, (sometimes collectively referred to as The Uists) have sandy beaches and wide cultivated areas of machair to the west and virtually uninhabited mountainous areas to the east. The highest peak here is Beinn Mhòr at 620 metres (2,034 ft).[8] The Uists and their immediate outliers have a combined area of 74,540 hectares (288 sq mi).[Note 2] Barra is 5,875 hectares (23 sq mi) in extent and has a rugged interior, surrounded by machair and extensive beaches.[10][11]

The land is deeply indented by arms of the sea such as Loch Ròg, Loch Seaforth and Loch nam Madadh. There are also more than 7,500 freshwater lochs in the Western Isles, about 24% of the total for the whole of Scotland.[12] North and South Uist and Lewis in particular have landscapes with a high percentage of freshwater and a maze and complexity of loch shapes. Harris has fewer large bodies of water but innumerable small lochans. Loch Langavat on Lewis is 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) long, and has several large islands in its midst, including Eilean Mòr. Although Loch Suaineabhal has only 25% of the Langavat's surface area it has a mean depth of 33 metres (108 ft) and is the most voluminous on the island.[13] Of Loch Sgadabhagh on North Uist it has been said that "there is probably no other loch in Britain which approaches Loch Scadavay in irregularity and complexity of outline."[14] Loch Bì is South Uist's largest loch and at 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) long it all but cuts the island in two.[15]

Populated islands

The inhabited islands had a total population of 26,502 at the time of the 2001 census. The largest settlement is Stornoway on Lewis.[3]

In addition to the North Ford (Oitir Mhòr) and South Ford causeways which connect North and South Uist, Benbecula and the northern of the two Grimsays, several other islands can now accessed by causeways and bridges. Great Bernera and Scalpay have bridge connections to Lewis and Harris respectively, Baleshare and Berneray are linked to North Uist, Eriskay to South Uist, Flodaigh, Fraoch-eilean and the southern Grimsay to Benbecula, and Vatersay to Barra by causeways.[15][16][17] This means that all of the inhabited islands are now connected to at least one other island by a land transport route.

| Island | Gaelic name | 2001 census population[3] |

|---|---|---|

| Lewis and Harris | Leòdhas agus na Hearadh | 19,918 |

| South Uist | Uibhist a Deas | 1,818 |

| North Uist | Uibhist a Tuath | 1,271 |

| Benbecula | Beinn nam Fadhla | 1,219 |

| Barra | Barraigh | 1,078 |

| Scalpay | Sgalpaigh | 322 |

| Great Bernera | Bearnaraigh Mòr | 233 |

| Grimsay (north) | Griomasaigh | 201 |

| Berneray | Beàrnaraigh | 136 |

| Eriskay | Eirisgeidh | 133 |

| Vatersay | Bhatarsaigh | 94 |

| Baleshare | Baile Sear | 49 |

| Grimsay (south) | Griomasaigh | 19 |

| Flodaigh | Flodaigh | 11 |

| Fraoch-eilean | Fraoch-eilean | ?[Note 3] |

| TOTAL (2001) | 26,502 |

Uninhabited islands

There are more than fifty uninhabited islands greater in size than 40 hectares (99 acres) in the Outer Hebrides, including the Barra Isles, Flannan Isles, Monach Islands, the Shiant Isles and the islands of Loch Ròg.[18] In common with the other main island chains of Scotland many of the more remote islands were abandoned during the 19th and 20th centuries, in some cases after continuous habitation since the prehistoric period.

Some of the smaller islands continue to contribute to modern culture. The "Mingulay Boat Song", although evocative of island life, was written after the abandonment of the island in 1938[19] and Taransay hosted the BBC television series ‘’Castaway 2000’’. Others have played a part in Scottish history. On 4 May 1746, the "Young Pretender" Charles Edward Stuart hid on Eilean Liubhaird with some of his men for four days whilst Royal Navy vessels patrolled the Minch.[20]

Smaller isles and skerries and other island groups pepper the North Atlantic surrounding the main islands. Some are not geologically part of the Outer Hebrides, but are administratively and in most cases culturally, part of Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. 73 kilometres (45 mi) to the west of Lewis lies St Kilda, now uninhabited except for a small military base.[21] A similar distance to the north of Lewis are North Rona and Sula Sgeir, two small and remote islands. While Rona used to support a small population who grew grain and raised cattle, Sula Sgeir is an inhospitable rock. Thousands of Northern Gannets nest here, and by special arrangement some of their young, known as "gugas" are harvested annually by the men of Ness.[22] The status of Rockall, which is 367 kilometres (228 mi) to the west of North Uist and decreed to be a part of the Western Isles by the Island of Rockall Act 1972, remains a matter of international dispute.[23][24]

Geology

Most of the islands have a bedrock formed from Lewisian gneiss. These are amongst the oldest rocks in Europe, having been formed in the Precambrian period up to 3000 million years ago. In addition to the Outer Hebrides, they form basement deposits on the Scottish mainland west of the Moine Thrust and on the islands of Coll and Tiree.[25] These rocks are largely igneous in origin, mixed with metamorphosed marble, quartzite and mica schist and intruded by later basaltic dykes and granite magma.[26] The gneiss's delicate pink colours are exposed throughout the islands and it is sometimes referred to by geologists as "The Old Boy".[27][Note 4]

Granite intrusions are found in the parish of Barvas in west Lewis, and another forms the summit plateau of the mountain Roineabhal in Harris. The granite here is anorthosite, and is similar in composition to rocks found in the mountains of the Moon. There are relatively small outcrops of Torridonian sandstone at Broad Bay near Stornoway. The Shiant Isles and St Kilda are formed from much later tertiary basalt and basalt and gabbros respectively.[6][29]

Climate

The Outer Hebrides have a cool temperate climate that is remarkably mild and steady for such a northerly latitude, due to the influence of the Gulf Stream. The average temperature for the year is 6°C (44°F) in January and 14°C (57°F) in summer. The average annual rainfall in Lewis is 1,100 millimetres (43 in) and sunshine hours range from 1,100 - 1,200 per annum. The summer days are relatively long and May to August is the driest period.[30] Winds are a key feature of the climate and even in summer there are almost constant breezes. According to the writer W. H. Murray if a visitor asks an islander for a weather forecast "he will not, like a mainlander answer dry, wet or sunny, but quote you a figure from the Beaufort Scale."[31] The are gales one day in six at the Butt of Lewis and small fish are blown onto the grass on top of 190 metres (620 ft) cliffs at Barra Head during winter storms.[32]

Prehistory

The Hebrides were originally settled in the Mesolithic era and have a diversity of important prehistoric sites. Eilean Dòmhnuill in Loch Olabhat on North Uist was constructed circa 3200-2800 BC and may be Scotland's earliest crannog.[33][34] The Callanish Stones dating from about 2900 BC are the finest example of a stone circle in Scotland, the 13 primary monoliths of between one and five metres high creating a circumference about 13 metres (43 ft) in diameter.[35][36][37] Cladh Hallan on South Uist, the only site in the UK where prehistoric mummies have been found and the impressive ruins of Dun Carloway broch on Lewis both date from the Iron Age.[38][39][40]

Etymology

| Pronunciation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Scots Gaelic: | A' Chomhairle | |

| Pronunciation: | [ə ˈxõ.ərˠʎə] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | An t-Eilean Fada | |

| Pronunciation: | [əɲ tʰʲelan fat̪ə] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Comhairle nan Eilean Siar | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈkʰõ.ərˠʎə nə ˈɲelan ˈʃiəɾ] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | guga | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈkukə] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Innse Gall | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈĩːʃə ˈkaulˠ̪] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Na h-Eileanan A-muigh | |

| Pronunciation: | [nə ˈhelanən əˈmuj] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Na h-Eileanan an Iar | |

| Pronunciation: | [nə ˈhelanən ə ˈɲiəɾ] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Na h-Eileanan Siar | |

| Pronunciation: | [nə ˈhelanən ˈʃiəɾ] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Oitir Mhòr | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈɔʰtʲɪɾʲ ˈvoːɾ] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Sloc na Béiste | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈs̪lˠ̪ɔʰk nə ˈpeːʃtʲə] | |

The earliest written references that have survived relating to the islands were made by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, where he states that there are 30 "Hebudes" and makes a separate reference to "Dumna" which latter name Watson (1926) concludes is unequivocally the Outer Hebrides. Writing about 80 years later in the period 140-150 AD, Ptolemy, drawing on the earlier naval expeditions of Agricola, also distinguished between the "Ebudes", of which he writes there were only five (and thus possibly meaning the Inner Hebrides) and Dumna.[41][42] Dumna is cognate with the Early Celtic dumnos and means the "deep-sea isle".[42][Note 5][Note 6]

Other early written references include the flight of the Nemed people from Ireland to "Domon", which is mentioned in the 12th century Lebor Gabála Érenn and a 13th century poem concerning Raghnall mac Gofraidh, then the heir to the throne of Mann and the Isles, who is said to have "broken the gate of Magh Domhna".[Note 7][42]

In Irish mythology the islands were the home of the Fomorians, described as "huge and ugly" and "ship men of the sea". The were pirates, extracting tribute from the coasts of Ireland and one of their kings was Indech mac Dé Domnand (i.e. Indech, son of the goddess Domnu, who ruled over the deep seas).[45]

In modern Gaelic the islands are sometimes referred to collectively as An t-Eilean Fada (the Long Island)[27] or Na h-Eileanan a-Muigh (the Outer Isles).[46] Innse Gall (islands of the foreigners or strangers) is also heard occasionally, a name that was originally used by mainland Highlanders when the islands were ruled by the Norse.[47]

The individual island and place names in the Outer Hebrides have mixed Gaelic and Norse origins. Various Gaelic terms are used repeatedly:[48]

| Common Gaelic terms | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

There are also several islands called Orasaigh from the Norse Örfirirsey meaning "tidal" or "ebb island".[48] |

History

In Scotland, the Celtic Iron Age way of life, often troubled but never extinguished by Rome, re-asserted itself when the legions abandoned any permanent occupation in 211 AD.[49][Note 8] The Roman's direct impact on the Highlands and Islands was scant and there is no evidence that they ever actually landed in the Outer Hebrides.[51]

The later Iron Age inhabitants of the northern and western Hebrides were probably Pictish, although the historical record is sparse. Hunter (2000) states that in relation to King Bridei I of the Picts in the sixth century AD: "As for Shetland, Orkney, Skye and the Western Isles, their inhabitants, most of whom appear to have been Pictish in culture and speech at this time, are likely to have regarded Bridei as a fairly distant presence.”[52] The island of Pabbay is the site of the Pabbay Stone, the only extant Pictish symbol stone in the Outer Hebrides. This 6th century stele shows a flower, V-rod and lunar crescent to which has been added a later and somewhat crude cross.[53]

Norse control

Viking raids began on Scottish shores towards the end of the 8th century AD and the Hebrides came under Norse control and settlement during the ensuing decades, especially following the success of Harald Fairhair at the Battle of Hafrsfjord in 872.[54][55] In the Western Isles Ketil Flatnose was the dominant figure of the mid 9th century, by which time he had amassed a substantial island realm and made a variety of alliances with other Norse leaders. These princelings nominally owed allegiance to the Norwegian crown, although in practice the latter's control was fairly limited.[56] Norse control of the Hebrides was formalised in 1098 when Edgar of Scotland formally signed the islands over to Magnus III of Norway.[57] The Scottish acceptance of Magnus III as King of the Isles came after the Norwegian king had conquered Orkney, the Hebrides and the Isle of Man in a swift campaign earlier the same year, directed against the local Norwegian leaders of the various islands petty kingdoms. By capturing the islands Magnus imposed a more direct royal control, although at a price. His skald Bjorn Cripplehand recorded that in Lewis "fire played high in the heaven" as "flame spouted from the houses" and that in the Uists "the king dyed his sword red in blood".[57][Note 9]

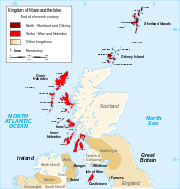

The Hebrides were now part of Kingdom of Mann and the Isles, whose kings were themselves vassals of the Kings of Norway. The Kingdom had two parts: the Suðr-eyjar or South Isles encompassing the Hebrides and the Isle of Man; and the Norðr-eyjar or North Isles of Orkney and Shetland. This situation lasted until the partitioning of the Western Isles in 1156, at which time the Outer Hebrides remained under Norwegian control while the Inner Hebrides broke out under Somerled, the Norse-Celtic kinsman of the Manx royal house.[59]

Following the ill-fated 1263 expedition of Haakon IV of Norway, the Outer Hebrides along with the Isle of Man, were yielded to the Kingdom of Scotland a result of the 1266 Treaty of Perth.[60] Although their contribution to the islands can still be found in personal and placenames, the archaeological record of the Norse period is scant. The best known find from this time is the Lewis chessmen, which date from the mid 12th century.[61]

Scots rule

As the Norse era drew to a close the Norse-speaking princes were gradually replaced by Gaelic-speaking clan chiefs including the MacLeods of Lewis and Harris, the MacDonalds of the Uists and MacNeil of Barra.[62][63] This transition did little to relieve the islands of internecine strife although by the early 14th century the MacDonald Lords of the Isles, based on Islay, were in theory these chiefs' feudal superiors and managed to exert some control.[64]

The growing threat that Clan Donald posed to the Scottish crown led to the forcible dissolution of the Lordship of the Isles by James IV in 1493, but although the king had the power to subdue the organised military might of the Hebrides, he and his immediate successors lacked the will or ability to provide an alternative form of governance.[65] The House of Stuart's attempts to control the Outer Hebrides were then at first desultory and little more than punitive expeditions. In 1506 the Earl of Huntly besieged and captured Stornoway Castle using cannon. In 1540 James V himself conducted a royal tour, forcing the clan chiefs to accompany him. There followed a period of peace, but all too soon the clans were at loggerheads again.[66]

In 1598 King James VI authorised some "Gentleman Adventurers" from Fife to civilise the "most barbarous Isle of Lewis". Initially successful, the colonists were driven out by local forces commanded by Murdoch and Neil MacLeod, who based their forces on Bearasaigh in Loch Ròg. The colonists tried again in 1605 with the same result but a third attempt in 1607 was more successful, and in due course Stornoway became a Burgh of Barony.[67][68] By this time Lewis was held by the Mackenzies of Kintail, (later the Earls of Seaforth), who pursued a more enlightened approach, investing in fishing in particular. The historian W. C. MacKenzie was moved to write:

At the end of the seventeenth century, the picture we have of Lewis that of a people pursuing their avocation in peace, but not in plenty. The Seaforths..., besides establishing orderly Government in the island.. had done a great deal to rescue the people from the slough of ignorance and incivility in which they found themselves immersed. But in the sphere of economics their policy apparently was of little service to the community.[69]

The Seaforth's royalist inclinations led to Lewis becoming garrisoned during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms by Cromwell's troops, who destroyed the old castle in Stornoway and in 1645 Lewismen fought at the Battle of Auldearn.[70] A new era of Hebridean involvement in the affairs of the wider world was about to commence.

British era

With the implementation of the Treaty of Union in 1707 the Western Isles became part of the new Kingdom of Great Britain, but the clan's loyalties to a distant monarch were not strong. A considerable number of islandmen "came out" in support of the Jacobite Earl of Mar in the "15" although the response to the 1745 rising was muted.[70] Nonetheless the aftermath of the decisive Battle of Culloden, which effectively ended Jacobite hopes of a Stuart restoration, were widely felt. The UK government's strategy was to estrange the clan chiefs from their kinsmen and turn their descendants into English-speaking landlords whose main concern was the revenues their estates brought rather than the welfare of those who lived on them. This may have brought peace to the islands, but in the following century it came at a terrible price.

The Highland Clearances of the 19th century destroyed communities throughout the Highlands and Islands as the human populations were evicted and replaced with sheep farms.[71] For example, Colonel Gordon of Cluny, owner of Barra, South Uist and Benbecula evicted thousands of islanders using trickery and cruelty and even offered to sell Barra to the government as a penal colony.[72] Islands such as Fuaigh Mòr were completely cleared of their populations and even today the subject is recalled with bitterness and resentment in some areas.[73] The position was exacerbated by the failure of the islands' kelp industry that thrived from the 18th century until the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815[74] and large scale emigration became endemic. Hundreds left North Uist for Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.[75] The pre-clearance population of the island had been almost 5,000, though by 1841 it had fallen to 3,870.[76][77]

For those who remained new economic opportunities emerged through the export of cattle, commercial fishing and tourism. During the summer season in the 1860s and 70s 5,000 inhabitants of Lewis could be found in Wick on the mainland of Scotland, employed on the fishing boats and at the quaysides.[78] Nonetheless emigration and military service became the choice of many[79] and the archipelago's populations continued to dwindle throughout the late 19th and 20th centuries. By 2001 the population of North Uist was only 1,271.[77]

The work of the Napier Commission and the Congested Districts Board, and the passing of the Crofting Act of 1886 helped, but social unrest continued.[80] In July 1906 grazing land on Vatersay was raided by landless men from Barra and its isles. Lady Gordon Cathcart took legal action against the "raiders" but the visiting judge took the view that she had neglected her duties as a landowner and that "long indifference to the necessities of the cottars had gone far to drive them to exasperation".[81] Millennia of continuous occupation notwithstanding, many of the remoter islands were abandoned - Mingulay in 1912, Hirta in 1930, and Ceann Iar in 1942 amongst them. This process involved a transition from these places being perceived as relatively self-sufficient agricultural economies[82] to a view becoming held by both island residents and outsiders alike that they lacked the essential services of a modern industrial economy.[83]

There were gradual economic improvements, amongst the most visible of which was the replacement of the traditional thatched black house with accommodation of a more modern design. The creation of the Highlands and Islands Development Board and the discovery of substantial deposits of North Sea oil in 1965, and the establishment of a unitary local authority for the islands in 1975 have all contributed to a degree of economic stability in recent decades.

Economy

The modern commercial activities centre on tourism, crofting, fishing, and weaving including the manufacture of Harris tweed. Some of the larger islands have development trusts that support the local economy and, in striking contrast to the 19th and 20th century domination by absentee landlords, more than two thirds of the Western Isles population now lives on community-owned estates.[84][85] However the economic position of the islands remains relatively precarious. The Western Isles, including Stornoway, are defined by Highlands and Islands Enterprise as an economically "Fragile Area" and they have an estimated trade deficit of some £163.4 million. Overall, the area is relatively reliant on primary industries and the public sector, and fishing and fish farming in particular are vulnerable to environmental impacts, changing market pressures and European legislation.[86]

There is some optimism about the possibility of future developments in for example, renewable energy generation, tourism, and education, and after declines in the 20th century the population has stabilised since 2003, although it is ageing.[86][87]

Politics and local government

From the passing of the Local Government (Scotland) Act 1889 to 1975 Lewis formed part of the county of Ross and Cromarty and the rest of the archipelago, including Harris, was part of Inverness-shire.[88]

The Western Isles became a unitary council area in 1975, although in most of the rest of Scotland similar unitary councils were not established until 1996.[89][90] Since then the islands have formed one of the 32 unitary council areas which now cover the whole country with the council becoming officially known by its Gaelic name, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar under the terms of the Local Government (Gaelic Names) (Scotland) Act 1997. The council has its base in Stornoway on Lewis and is often known locally simply as "the Comhairle" or "a' Chomhairle".[91]

The name for the British Parliament constituency covering this area is Na h-Eileanan an Iar, the seat being held by Angus MacNeil MP since 2005, whilst the Scottish Parliament constituency for the area is Western Isles, the incumbent being Alasdair Allan MSP.

Gaelic language

The Outer Hebrides have historically been a very strong Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig) speaking area. Both in the 1901 and 1921 census, all parishes were reported to be over 75% Gaelic speaking, including areas of high population density such as Stornoway. However, the Education (Scotland) Act 1872 led to generations of Gaels being forbidden to speak their native language in the classroom, and is now recognised as having dealt a major blow to the language. People still living can recall being beaten for speaking Gaelic in school.[92][93] Nonetheless, by 1971 most areas were still more than 75% Gaelic speaking – with the exception of Stornoway, Benbecula and South Uist at 50-74%.[94]

In the 2001 census, each island overall was over 50% Gaelic speaking – South Uist (71%), Harris (69%), Barra (68%), North Uist (67%), Lewis (56%) and Benbecula (56%). With 59.3% of Gaelic speakers or a total of 15,723 speakers, this made the Outer Hebrides the most strongly coherent Gaelic speaking area in Scotland.[94][95]

Most areas are between 60-74% Gaelic speaking and the areas with the highest density of over 80% are Scalpay near Harris, Newtonferry and Kildonan, whilst Daliburgh, Linshader, Eriskay, Brue, Boisdale, West Harris, Ardveenish, Soval, Ness, and Bragar all have more than 75%. The areas with the lowest density of speakers are Stornoway (44%), Braigh (41%), Melbost (41%), and Balivanich (37%).[94]

The Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act was enacted by the Scottish Parliament in 2005 in order to provide continuing support for the language.[96]

Transport

Scheduled ferry services between the Outer Hebrides and the Scottish Mainland and Inner Hebrides operate on the following routes:

- Oban to Castlebay on Barra and Lochboisdale on South Uist

- Uig on Skye to Tarbert on Harris

- Uig on Skye to Lochmaddy on North Uist

- Ullapool to Stornoway on Lewis

- Tiree to Castlebay, Barra (summer only)

Other ferries operate between some of the islands.[97]

National Rail services are available for onward journeys, from stations at Oban, which has direct services to Glasgow. However, parliamentary approval notwithstanding, plans in the 1890s to lay a railway connection to Ullapool were unable to obtain sufficient funding.[98]

There are scheduled flights from Stornoway, Benbecula and Barra airports both inter-island and to the mainland. Barra's airport is the only one in the world to have scheduled flights landing on a beach. At high water the runways are under the sea so flight times vary with the tide.[99][100]

Shipwrecks

The archipelago is exposed to wind and tide, and lighthouses are sited as an aid to navigation at locations from Barra Head in the south to the Butt of Lewis in the north.[101] There are numerous sites of wrecked ships and the Flannan Isles are the location of an enduring mystery which occurred in December 1900, when all three lighthouse keepers vanished without trace.[102]

The Annie Jane, a three-masted immigrant ship out of Liverpool bound for Montreal, Canada, struck rocks off the West Beach of Vatersay during a storm on Tuesday 28 September 1853. Within ten minutes the ship began to founder and break up casting 450 people into the raging sea. In spite of the conditions, islanders tried to rescue the passengers and crew. The remains of 350 men, women and children were buried in the dunes behind the beach and a small cairn and monument marks the site.[103]

The tiny Beasts of Holm of the east coast of Lewis were the site of the sinking of the HMS Iolaire during the first few hours of 1919,[104] one of the worst maritime disasters in United Kingdom waters during the 20th century. Calvay in the Sound of Barra provided the inspiration for Compton MacKenzie's novel Whiskey Galore after the SS Politician ran aground there with a cargo of single malt in 1941.

Religion, culture and sport

Christianity has deep roots in the Western Isles, but owing mainly to the different allegiances of the clans in the past, the people in the northern islands (Lewis, Harris, North Uist) have historically been predominantly Presbyterian, and those of the southern islands (Benbecula, South Uist, Barra) predominantly Roman Catholic.[105]

At the time of the 2001 Census, 42% of the population were recorded as Church of Scotland, with 13% Roman Catholic and 28% "Other Christian". Many of this last group belong to the Free Church of Scotland, known for its strict observance of the Sabbath. 11% stated that they had no religion.[Note 10] There are also small Episcopalian congregations in Lewis and Harris and the Outer Hebrides are part of the Diocese of Argyll and the Isles in both the Episcopalian and Catholic traditions.[107][108]

Gaelic music is popular in the islands and the Lewis and Harris Traditional Music Society plays and active role in promoting the genre.[109] Fèis Bharraigh began in 1981 with the aim of developing the practice and study of the Gaelic language, literature, music, drama and culture on the islands of Barra and Vatersay. A two week long festival, it has inspired 43 other feisean throughout Scotland.[110] The Lewis Pipe Band was founded in 1904 and the Lewis and Harris Piping Society in 1977.[109]

Outdoor activities including rugby, football, golf, shinty, fishing, riding, canoeing, athletics, and multi-sports are popular in the Western Isles. The Hebridean Challenge is an adventure race run in five daily stages, which takes place along the length of the islands and includes hill and road running, road and mountain biking, short sea swims and demanding sea kayaking sections. There are four main sports centres: Ionad Spors Leodhais in Stornoway, which has a 25m swimming pool; Harris Sports Centre; Lionacleit Sports Centre on Benbecula; and Castlebay Sports Centre on Barra. The Western Isles is a member of the International Island Games Association.[111][112]

South Uist is home to the Askernish Golf Course. The oldest links in the Outer Hebrides, it was designed by Old Tom Morris. Although it was in use until the 1930s, its existence was largely forgotten until 2005 and it is now being restored to Morris's original design.[113][114]

Natural history

Much of the archipelago is a protected habitat including both the islands and the surrounding waters. There are 53 Sites of Special Scientific Interest of which the largest are Loch an Duin, North Uist at 15,100 hectares (37,000 acres) and North Harris, which is 12,700 hectares (31,000 acres) in extent.[115][116]

Loch Druidibeg on South Uist is a National Nature Reserve owned and managed by Scottish Natural Heritage. The reserve covers 1,677 hectares across the whole range of local habitats.[117] Over 200 species of flowering plants have been recorded on the reserve, some of which are nationally scarce.[118] South Uist is considered the best place in the UK for the aquatic plant Slender Naiad, which is a European Protected Species.[119][120]

There has been considerable controversy over Hedgehogs on the Uists. The animals are not native to the islands, having been introduced in the 1970s to reduce garden pests and their spread posed a threat to the eggs of ground nesting wading birds. In 2003 Scottish Natural Heritage undertook culls of hedgehogs in the area although they were halted in 2007, with trapped animals now being relocated to the mainland.[121][122]

Nationally important populations of breeding waders are present in the Outer Hebrides including Common Redshank, Dunlin, Lapwing and Ringed Plover. The islands also provide a habitat for other important species such as Corncrake, Hen Harrier, Golden Eagle and Otter. Offshore, Basking Shark and various species of whale and dolphin can be seen regularly,[123] and the remoter islands' seabird populations are of international significance. St Kilda has 60,000 Northern Gannets, amounting to 24% of the world population, 49,000 breeding pairs of Leach's Petrel, up to 90% of the European population and 136,000 pairs of Puffin and 67,000 Northern Fulmar pairs, about 30% and 13% of the respective UK totals.[124] Mingulay is an important breeding ground for Razorbills, with 9,514 pairs, 6.3% of the European population.[125]

The bumblebee Bombus jonellus var. hebridensis is endemic to the Hebrides and there are local variants of the Dark Green Fritillary and Green-veined White butterflies.[126] T. t. hirtensis is subspecies of wren confined to St Kilda.[127]

See also

- Hebridean Myths and Legends

- List of places in the Western Isles

- List of Kings of the Isle of Man and the Isles

- List of islands of Scotland

- Ljótólfr - a 12th-century nobleman from Lewis

- Leod - the 13th-century eponymous ancestor of Clan MacLeod

References

- Notes

- ↑ The island does not have a common name in either English or Gaelic and is referred to as "Lewis and Harris", "Lewis with Harris", "Harris with Lewis" etc.[6]

- ↑ The quoted area figure includes the Uists themselves and the islands to which they are linked by causeways and bridges.[9]

- ↑ This island is at (grid reference NF860580) and the evidence of both Ordnance Survey maps and photographs (e.g. "Houses on Seana Bhaile" Geograph. Retrieved 10 August 2009) indicates a resident population. There is even a name, "Seana Bhaile" for the main settlement. However, neither the census nor the main reference work (Haswell-Smith 2004) refer to the island at all. Its population is presumably included in nearby Grimsay by the census.

- ↑ Lewisian gneiss is sometimes described as the oldest rock found in Europe, but trondhjemite gneiss recently measured at Siurua in Finland has been dated to 3.4–3.5 Ga.[28]

- ↑ Pliny probably took his information from Pytheas of Massilia who visited Britain sometime between 322 and 285 BC. It is possible that Ptolemy did as well, as Agricola's information about the west coast of Scotland was of poor quality.[41][42] Breeze also suggests that Dumna might be Lewis and Harris, the largest island of the Outer Hebrides although he conflates this single island with the name "Long Island".[41]

- ↑ Watson states that the meaning of Ptolemy's "Eboudai" is unknown and that the root may be pre-Celtic.[43] Murray (1966) claims that Ptolemy's "Ebudae" was originally derived from the Old Norse Havbredey, meaning "isles on the edge of the sea". This idea is often repeated but no firm evidence of this derivation has emerged.[44]

- ↑ Magh Domhna means "the plain of Domhna (or Domon)", but the precise meaning of the text is not clear.[42]

- ↑ Hanson (2003) writes: "For many years it has been almost axiomatic in studies of the period that the Roman conquest must have had some major medium or long-term impact on Scotland. On present evidence that cannot be substantiated either in terms of environment, economy, or, indeed, society. The impact appears to have been very limited. The general picture remains one of broad continuity, not of disruption.... The Roman presence in Scotland was little more than a series of brief interludes within a longer continuum of indigenous development."[50]

- ↑ Thompson provides a more literal translation: "Fire played in the fig-trees of Liodhus; it mounted up to heaven. Far and wide the people were driven to flight. The fire gushed out of the houses".[58]

- ↑ The 2001 census statistics used are based on local authority areas but do not specifically identify Free Church or Episcopal adherents. 4% of the respondents did not answer this census question and the total for all other religions combined is 1 per cent.[106]

- Footnotes

- ↑ "Unitary Authority Fact Sheet - Population and Area" University of Edinburgh School of GeoSciences. Retrieved 30 May 2010.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Thompson (1968) p. 14

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 General Register Office for Scotland (2003)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 289

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 262

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Thompson (1968) p. 13

- ↑ Murray (1966) pp. 171, 198

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 236-45

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 206

- ↑ Rotary Club (1995) p. 106

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 218-22

- ↑ "Botanical survey of Scottish freshwater lochs" SNH Information and Advisory Note Number 4. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- ↑ Murray and Pullar (1910) "Lochs of Lewis" Page 216, Volume II, Part II. National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ↑ Murray and Pullar (1910) "Lochs of North Uist" Page 188, Volume II, Part II. National Library of Scotland. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Get-a-map". Ordnance Survey. Retrieved 1–15 August 2009.

- ↑ "Fleet Histories" Caledonian MacBrayne. Retrieved 3 August 2009.

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 205, 253

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 206, 262

- ↑ "Mingulay Boat Song" Cantaria. Retrieved 26 December 2006.

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 282–83

- ↑ Thompson (1968) pp. 187-89

- ↑ Thompson (1968) pp. 182-85

- ↑ Oral Questions to the Minister of Foreign Affairs. Dáil Éireann. 1 November 1973. http://historical-debates.oireachtas.ie/D/0268/D.0268.197311010090.html. Retrieved 17 January 2007.

- ↑ MacDonald, Fraser (2006). "The last outpost of Empire: Rockall and the Cold War". Journal of Historical Geography 32: 627–647. doi:10.1016/j.jhg.2005.10.009. http://www.landfood.unimelb.edu.au. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ↑ Gillen (2003) p. 44

- ↑ McKirdy et al. (2007) p. 95

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Murray (1966) p. 2

- ↑ Lalli, Katja and Huhma, Hannu "The oldes rock of Europe at Siurua" (sic) (pdf) Fifth International Dyke Conference: Rovaniemi, Finland. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- ↑ McKirdy et al. (2007) p. 94

- ↑ Thompson (1968) pp. 24-26

- ↑ Murray (1973) p. 79

- ↑ Murray (1973) pp. 79-81

- ↑ Armit (1998) p. 34.

- ↑ Crone, B.A. (1993) "Crannogs and chronologies" (pdf) Proceedings of the Society of Antiquarians of Scotland. 123 pp. 245-54. Retrieved 1 May 2008.

- ↑ Li (2005) p. 509.

- ↑ Murray (1973) p. 122

- ↑ "Lewis, Callanish, 'Tursachan' " RCAHMS. Retrieved 21 April 2008.

- ↑ "Mummification in Bronze Age Britain" BBC History. Retrieved 11 February 2008.

- ↑ "The Prehistoric Village at Cladh Hallan". University of Sheffield. Retrieved 21 February 2008.

- ↑ "AD 200 - Valtos: brochs and wheelhouses" archaeology.co.uk Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Breeze, David J. "The ancient geography of Scotland" in Smith and Banks (2002) pp. 11-13

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 42.3 42.4 Watson (1926) pp. 40-41

- ↑ Watson (1926) p. 38

- ↑ Murray (1966) p. 1

- ↑ Watson (1926) pp. 41-42 quoting Lebor na hUidre and the Book of Leinster.

- ↑ "The Gaelic—English Dictionary" Bookrags.com. Retrieved 1 May 2010.

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 104

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Mac an Tàilleir (2003) various pages.

- ↑ Hanson (2003) p. 198

- ↑ Hanson (2003) p. 216.

- ↑ Hunter (2000) pp. 38-39

- ↑ Hunter (2000) pp. 44, 49

- ↑ Miers (2008) p. 367

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 74

- ↑ Rotary Club (1995) p. 12

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 78

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 Hunter (2000) p. 102

- ↑ Thompson (1968) p 39

- ↑ "The Kingdom of Mann and the Isles" thevikingworld.com Retrieved 6 July 2010.

- ↑ Hunter (2000) pp. 109-111

- ↑ Thompson (1968) p. 37

- ↑ Thompson (1968) p. 39

- ↑ Rotary Club (1995) pp. 27, 30

- ↑ Hunter (2000) pp. 127, 166

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 143

- ↑ Thompson (1968) pp. 40-41

- ↑ Rotary Club (1995) pp. 12-13

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) p. 312

- ↑ Thompson (1968) p. 41. It is not clear from the text which of MacKenzie's five books quoted in the bibliography spanning the years 1903-52 the quote is taken from.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Thompson (1968) pp. 41-42

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 212

- ↑ Rotary Club (1995) p. 31

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp 306-07

- ↑ Hunter (2000) pp. 247, 262

- ↑ Lawson, Bill (10 September 1999) "From The Outer Hebrides to Cape Breton - Part II". globalgenealogy.com. Retrieved 14 October 2007.

- ↑ "Hebridean Princess Scotland" (pdf) hebridean.co.uk. Retrieved 17 October 2007.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 "North Uist (Uibhist a Tuath)" Undiscovered Scotland Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 292

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 343

- ↑ Hunter (2000) p. 320

- ↑ Buxton (1995) p. 125

- ↑ See for example Hunter (2000) pp. 152–158

- ↑ See for example Maclean (1977) Chapter 10: "Arcady Despoiled" pp. 125–35

- ↑ "Directory of Members" DTA Scotland. Retrieved 15 July 2007.

- ↑ "The quiet revolution". (19 January 2007) West Highland Free Press. Broadford, Skye.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 "Factfile - Economy" Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ "Factfile - Population" Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ Keay and Keay (1994) pp. 542, 821

- ↑ "Areas of Scotland" ourscotland.co.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ↑ "Place-names of Scotland" scotlandsplaces.gov.uk. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ↑ Department of Education (January 2008) "Review of Educational Provision and the Comhairle’s Future Strategy for the Schools Estate: Daliburgh School, Isle of South Uist" (pdf) Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. Retrieved 1 June 2010.

- ↑ "Gaelic Education After 1872" simplyscottish.com. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ↑ Morris (2001) p. 416

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 94.2 Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2004) 1901-2001 Gaelic in the Census (PowerPoint) Linguae Celticae. Retrieved 01 June 2008

- ↑ "Census 2001 Scotland: Gaelic speakers by council area" Comunn na Gàidhlig. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ↑ “"About us", Bòrd na Gàidhlig. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- ↑ "Timetables and Fares" Caledonian MacBrayne. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ "Garve and Ullapool Railway Bill" Hansard. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ↑ "Barra Airport". Highlands and Islands Airports Limited. http://www.hial.co.uk/barra-airport.html. Retrieved 6 April 2009.

- ↑ "Barra Airport". Undiscovered Scotland. http://www.undiscoveredscotland.co.uk/barra/airport/index.html. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ "Lighthouse Library" Northern Lighthouse Board. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 329-31

- ↑ "Annie Jane Memorial - the story". Isle of Vatersay. http://www.isleofvatersay.com/Vatersay2chist.html. Retrieved 8 July 2010.

- ↑ Thompson (1968) p. 76.

- ↑ Clegg, E.J. "Fertility and Development in the Outer Hebrides; The Confounding Effcets of Religion" in Malhotra (1992) p. 88

- ↑ Pacione, Michael (2005) "The Geography of Religious Affiliation in Scotland". The Professional Geographer 57(2). Oxford. Blackwell.

- ↑ "Diocese of Argyll and the Isles" argyllandtheisles.org.uk. Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ↑ "RC Diocese of Argyll and the Isles" dioceseofargyllandtheisles.org Retrieved 16 June 2010.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 Rotary Club (1995) p. 39.

- ↑ "History" Feis Bharraigh. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ "Member Profile: Western Isles" IIGA. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ "Sgoil Lionacleit" Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ "Askernish Golf Course" Storas Uibhist. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ David Owen (April 20, 2009). "The Ghost Course". New Yorker. http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2009/04/20/090420fa_fact_owen. Retrieved 4 July 2010.

- ↑ "Western Isles Transitional Programme Strategy" Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- ↑ Rotary Club (1995) p. 10

- ↑ "Loch Druidibeg National Nature Reserve: Where Opposites Meet". (pdf) SNH. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- ↑ "South Uist and Eriskay attractions" isle-of-south-uist.co.uk. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ "Higher plant species: 1833 Slender naiad" JNCC. Retrieved 29 July 2007.

- ↑ "Statutory Instrument 1994 No. 2716 " Office of Public Sector Information. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ "Campaign to stop the slaughter of over 5000 Hedgehogs on the Island of Uist". Epping Forest Hedgehog Rescue. http://www.thehedgehog.co.uk/campaign.htm. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ↑ Ross, John (21 February 2007). "Hedgehogs saved from the syringe as controversial Uist cull called off". Edinburgh: The Scotsman.

- ↑ "Western Isles Biodiversity: Biodiversity Audit - Main report" Comhairle nan Eilean Siar. Retrieved 5 July 2010.

- ↑ Benvie (2004) pp. 116, 121, 132–34.

- ↑ "Mingulay birds". National Trust for Scotland. http://www.nts-seabirds.org.uk/properties/mingulay/mingulay_breeding.aspx/. Retrieved 16 February 2007.

- ↑ Thompson (1968) p. 21

- ↑ Maclean (1972) p. 21.

- General references

- Armit, Ian (1998) Scotland's Hidden History. Tempus (in association with Historic Scotland). ISBN 0-7486-6067-4

- Ballin Smith, B. and Banks, I. (eds) (2002) In the Shadow of the Brochs, the Iron Age in Scotland. Stroud. Tempus. ISBN 075242517X

- Benvie, Neil (2004) Scotland's Wildlife. London. Aurum Press. ISBN 1854109782

- Buxton, Ben (1995) Mingulay: An Island and Its People. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 1874744246

- General Register Office for Scotland (28 Nov 2003) Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 15 September 2007.

- Gillen, Con (2003) Geology and landscapes of Scotland. Harpenden. Terra Publishing. ISBN 1903544092

- Hanson, William S. "The Roman Presence: Brief Interludes", in Edwards, Kevin J. & Ralston, Ian B.M. (Eds) (2003) Scotland After the Ice Age: Environment, Archaeology and History, 8000 BC - AD 1000. Edinburgh. Edinburgh University Press.

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish. (2004) The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh. Canongate. ISBN 1-84195-454-3

- Hunter, James (2000) Last of the Free: A History of the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Edinburgh. Mainstream. ISBN 1840183764

- Keay, J. & Keay, J. (1994) Collins Encyclopaedia of Scotland. London. HarperCollins. ISBN 0002550822

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain (2003) Placenames/Ainmean-àite le buidheachas (pdf). Pàrlamaid na h-Alba. Retrieved 6 October 2009.

- McKirdy, Alan Gordon, John & Crofts, Roger (2007) Land of Mountain and Flood: The Geology and Landforms of Scotland. Edinburgh. Birlinn. ISBN 9781841583570

- Maclean, Charles (1977) Island on the Edge of the World: the Story of St. Kilda. Edinburgh. Canongate. ISBN 0903937417

- Malhotra, R. (1992) Anthropology of Development: Commemoration Volume in Honour of Professor I.P. Singh. New Delhi. Mittal. ISBN 8170993288

- Li, Martin (2005) Adventure Guide to Scotland. Hunter Publishing. Retrieved 19 May 2010.

- Miers, Mary (2008) The Western Seaboard: An Illustrated Architectural Guide. The Rutland Press. ISBN 9781873190296

- Murray, Sir John and Pullar, Laurence (1910) Bathymetrical Survey of the Fresh-Water Lochs of Scotland, 1897-1909. London. Challenger Office.

- Murray, W.H. (1966) The Hebrides. London. Heinemann.

- Murray, W.H. (1973) The Islands of Western Scotland: the Inner and Outer Hebrides. London. Eyre Methuen. ISBN 0413303802

- Ross, David (2005) Scotland - History of a Nation. Lomond. ISBN 0947782583

- Rotary Club of Stornoway (1995) The Outer Hebrides Handbook and Guide. Machynlleth. Kittwake. ISBN 0951100351

- Thompson, Francis (1968) Harris and Lewis, Outer Hebrides. Newton Abbot. David & Charles. ISBN 0715342606

- Watson, W. J. (1994) The Celtic Place-Names of Scotland. Edinburgh; Birlinn. ISBN 1841583235. First published 1926.

External links

- Western Isles at the Open Directory Project

- Outer Hebrides travel guide from Wikitravel

- Stornoway Port Authority

- Comhairle nan Eilean Siar

- 2001 Census Results for the Outer Hebrides

- Sites deriving partly from the original Virtual Hebrides

Historical footnote: Many websites of the Outer Hebrides derive content from the Eolas Virtual Hebrides website. Eolas Media went into voluntary liquidation in 2000 and the Eolas TV company became MacTV. The web design team became Reefnet and the content has largely found a home on GlobalGuide.Org.

- Hebrides.com Photographic website from ex-Eolas Sam Maynard

- Global Guide Hebrides Content website from ex-Eolas Scott Hatton

- www.visithebrides.com Western Isles Tourist Board site from Reefnet

- Virtual Hebrides.com Content from the VH which went its own way and became Virtual Scotland.

- hebrides.ca Home of the Quebec-Hebridean Scots who were cleared from Lewis to Quebec 1838-1920's

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||