Surfing

- This article focuses on stand-up surfing. For other uses see Surfing (disambiguation)

Surfing is a surface water sport.

Two major subdivisions within stand-up surfing are longboarding and shortboarding, reflecting differences in surfboard design including surfboard length, and riding style.

In tow-in surfing (most often, but not exclusively, associated with big wave surfing), a motorized water vehicle, such as a personal watercraft tows the surfer into the wave front, helping the surfer match a large wave's higher speed, a speed that is generally, but not exclusively a speed that a self-propelled surfer can not match.

Surfing-related sports such as paddleboarding and sea kayaking do not require waves, and other derivative sports such as kitesurfing and windsurfing rely primarily on wind for power, yet all of these platforms may also be used to ride waves.

Recently with the use of V-drive boats, wake surfing, riding the boat wake has emerged.

Contents |

Origin

Surfing was a central part of ancient Polynesian culture. Surfing was first observed by Europeans at Tahiti in 1767, by the crew members of the Dolphin. Later, Lieutenant James King wrote about the art[1] when completing the journals of Captain James Cook upon Cook's death in 1779. When Mark Twain visited Hawaii in 1866 he wrote,

- "In one place we came upon a large company of naked natives, of both sexes and all ages, amusing themselves with the national pastime of surf-bathing."[2]

References to surf riding on planks and single canoe hulls are also verified for pre-contact Samoa, where surfing was called fa'ase'e or se'egalu (see Kramer, Samoa Islands) and Tonga.

Surf waves

Swell is generated when wind blows consistently over a large area of open water, called the wind's fetch. The size of a swell is determined by the strength of the wind and the length of its fetch and duration. Accordingly, surf tends to be larger and more prevalent on coastlines exposed to large expanses of ocean traversed by intense low pressure systems.

Local wind conditions affect wave quality, since the surface of a wave can become choppy in blustery conditions. Ideal conditions include a light to moderate "offshore" wind, because it blows into the front of the wave, making it a "barrel" or "tube" wave.

The most important influence on wave shape is the topography of the seabed directly behind and immediately beneath the breaking wave. The contours of the reef or bar front becomes stretched by diffraction. Each break is different, since the underwater topography of one place is unlike any other. At beach breaks, sandbanks change shape from week to week. Surf forecasting is aided by advances in information technology. Mathematical modeling graphically depicts the size and direction of swells around the globe.

Swell regularity varies across the globe and throughout the year. During winter, heavy swells are generated in the mid-latitudes, when the north and south polar fronts shift toward the Equator. The predominantly westerly winds generate swells that advance eastward, so waves tend to be largest on west coasts during winter months. However, an endless train of mid-latitude cyclones cause the isobars to become undulated, redirecting swells at regular intervals toward the tropics.

East coasts also receive heavy winter swells when low-pressure cells form in the sub-tropics, where slow moving highs inhibits their movement. These lows produce a shorter fetch than polar fronts, however they can still generate heavy swells, since their slower movement increases the duration of a particular wind direction. The variables of fetch and duration both influence how long wind acts over a wave as it travels, since a wave reaching the end of a fetch behaves as if the wind died.

During summer, heavy swells are generated when cyclones form in the tropics. Tropical cyclones form over warm seas, so their occurrence is influenced by El Niño & La Niña cycles. Their movements are unpredictable. They can move westward as in 1979, when Tropical Cyclone Kerry wandered for three weeks across the Coral Sea and into Queensland before dissipating.

Surf travel and some surf camps offer surfers access to remote, tropical locations, where tradewinds ensure offshore conditions. Since winter swells are generated by mid-latitude cyclones, their regularity coincides with the passage of these lows. Swells arrive in pulses, each lasting for a couple of days, with a few days between each swell.

Wave intensity

Classification parameters

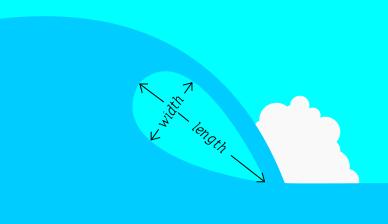

- Tube shape defined by length to width ratio

- Square: <1:1

- Round: 1-2:1

- Almond: >2:1

- Tube speed defined by angle of peel line

- Fast: 30°

- Medium: 45°

- Slow: 60°

| Fast | Medium | Slow | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Square | The Cobra | Teahupoo | Shark Island |

| Round | Speedies, Gnaraloo | Banzai Pipeline | |

| Almond | Lagundri Bay, Superbank | Jeffreys Bay, Bells Beach | Angourie Point |

Artificial reefs

The value of good surf has even prompted the construction of artificial reefs and sand bars to attract surf tourism. Of course, there is always the risk that one's vacation coincides with a "flat spell." Wave pools aim to solve that problem, by controlling all the elements that go into creating perfect surf, however there are only a handful of wave pools that can simulate good surfing waves, owing primarily to construction and operation costs and potential liability.

The availability of free model data from the NOAA has allowed the creation of several surf forecasting websites.

An artificial reef known as Chevron Reef, was constructed in El Segundo, California in hopes of creating a new surfing area. However, the project was a failure, and the reef failed to produce any quality waves .

Surfers and surf culture

Surfers represent a diverse culture based on riding the waves. Some people practice surfing as a recreational activity while others make it the central focus of their lives. Within the United States, surfing culture is most dominant in California, Florida and Hawaii. Some historical markers of the culture included the woodie, the station wagon used to carry surfers' boards, as well as boardshorts, the long swim suits typically worn while surfing.

The sport of surfing now represents a multi-billion dollar industry especially in clothing and fashion markets. Some people make a career out of surfing by receiving corporate sponsorships.

When the waves were flat, surfers persevered with sidewalk surfing, which is now called skateboarding. Sidewalk surfing has a similar feel to surfing and requires only a paved road or sidewalk. To create the feel of the wave, surfers even sneak into empty backyard swimming pools to ride in, known as pool skating.

Maneuvers

Surfing begins when the surfer finds a ridable wave on the horizon and then attempts to match its speed (by paddling or sometimes, by tow-in). Once the wave starts to carry the surfer forward, the surfer stands up and proceeds to ride down the face of the wave, generally staying just ahead of the breaking part (white water) of the wave (in a place often referred to as the pocket or the curl). A common problem for beginners is being unable to catch the wave in the first place, and one sign of a good surfer is the ability to catch a difficult wave that other surfers cannot.

Surfers' skills are not tested only in their ability to control their board in challenging conditions and/or catch and ride challenging waves, but by their ability to execute maneuvers such as turning and carving. Some of the common turns have become recognizable tricks such as the cutback (turning back toward the breaking part of the wave), the floater (riding on the top of the breaking curl of the wave), and off the lip (banking off the top of the wave). A newer addition to surfing is the progression of the air where a surfer propels oneself off the wave and re-enters. Some of these maneuvers are executed to extreme degrees, as with off-the-lips where a surfer over-rotates his turn and re-enters backward, or airs done in the same fashion, recovering either with re-rotation or continuing the over-rotation to come out with his nose forward again.

Tube ride

The tube ride is a manouevre performed in the sport of surfing. When a wave begins to break, it often creates a hollow section as it peels down the sandbank or reef bottom, enabling the experienced surfer to position him / her self in the hollow part of the wave, also known as the tube. The surfer can be completely surrounded by water for several seconds (sometimes much longer depending upon the wave) until the wave forces him / her to exit the tube and go back out onto the open wave face. Given the degree of difficulty experienced whilst riding a tube, surfers often fall off their surfboards before exiting the tube cleanly. Strong tube riding skills can only be acquired from years of experience riding hollow waves and learning to anticipate how the wave will break, thus enabling you to stay inside the tube longer, or exit quickly before the wave collapses on top of you. Some of the world's best known waves for tube riding include Pipeline on the North shore of Oahu, Teahupoo in Tahiti and G-Land in Java.

Hanging Ten and Hanging Five are moves usually specific to longboarding. Hanging Ten refers to having both feet on the front end of the board with all of the surfer's toes off the edge, also known as noseriding. Hanging Five is having just one foot near the front, toes off the edge. Hanging Ten was first made famous by James (Rip) Carman from the early Californian surfing beaches.

Cutback: Generating speed down the line and then turning up the face to reverse direction. Has the effect of slowing the rider down to keep up with slower wave sections that appear after a fast section, for example a drop in.

Floater: Popping up on the lip of the wave and coming down with the lip. Can be used at the end of a wave when the wave section is closing out. Very easy and popular on small waves.

Top-Turn: Simple turn off the top of the wave. Used sometimes to generate speed and sometimes to shoot spray.

Air / Aerial: Popping up over the lip into the air. Many types include ollies, lien airs, method airs, and other skateboard airs.

Common terms

- Air/Aerial—riding the board briefly into the air above the wave, landing back upon the wave, and continuing to ride

- Bottom turn—the first turn at the bottom of the wave

- Carve—turns (often accentuated)

- Caught inside- When a surfer is paddling out and cannot get past the breaking surf to the safer part of the ocean to find a wave.

- Close-out—When the wave breaks in front of, or potentially on top of, the rider. A wave is said to be "closed-out" when the wave breaks at every position along the face at once.

- Cutback—a turn cutting back toward the breaking part of the wave

- Drop in—dropping into (engaging) the wave, most often as part of standing up

- Duck dive—pushing the board underwater, nose first, and diving under an oncoming wave instead of riding it

- Fade—on take-off, aiming toward the breaking part of the wave, before turning sharply and surfing in the direction the wave is breaking

- Fins-free snap (or "fins out")—a sharp turn where the surfboard's fins slide off the top of the wave

- Floater—riding up on the top of the breaking part of the wave, and coming down with it (invented at Terrigal Beach, Central Coast Australia)

- Goofy foot—Left foot on back of board

- Grom/Grommet—young surfer (anyone younger than you)

- Hang Heels—Facing backwards and putting the surfers' heels over the edge of a longboard.

- Hang-five/hang ten—putting five or ten toes respectively over the nose of a longboard

- Hang-loose—Generally meaning "catch that wave" or "well done". This message can be sent by raising a hand with the thumb and pinkie fingers up while the index, middle and ring fingers remain folded over the palm. Then twisting the wrist back and forth as if waving goodbye.

- Off the Hook—If a surfer were to say the swell is 'off the hook', he generally means that the surfspot he is referring to is of a good size, shape and look.

- Off the Top—a turn on the top of a wave, either sharp or carving

- Over the falls—When a surfer falls and the wave carries him in a circular motion with the lip of the wave, also referred to as the "wash cycle", being "pitched over" and being "sucked over" because the wave can suck the surfer off of the bottom and draw him or her "over the falls."

- Pearl—accidentally driving the nose of the board underwater, generally ending the ride

- Pop-up—Going from lying on the board to standing, all in one jump

- Pump—an up/down carving movement that generates speed along a wave

- Re-entry—hitting the lip vertically and re-reentering the wave in quick succession.

- Regular/Natural foot—Right foot on back of board

- Rolling—, Turtle Roll; Flipping a longboard up-side-down, nose first and pulling through a breaking or broken wave when paddling out to the line-up

- Shoulder—the unbroken part of the wave

- Snake—When a surfer who doesn't have the right of way, steals a wave from another surfer.

- Snaking, Drop in on, cut off, or "burn"—taking off on a wave in front of someone closer to the peak (considered inappropriate)

- Snaking/Back-Paddling—paddling around someone to get into the best position for a wave (in essence, stealing it)

- Snap—a quick, sharp turn off the top of a wave

- Stall—slowing down by shifting weight to the tail of the board or putting a hand in the water

- Switch-foot—having equal ability to surf regular foot or goofy foot (i.e. left foot forward or right foot forward)—like being ambidextrous

- Take-off—the start of a ride

- Tube riding/Getting barreled—riding inside the hollow curl of a wave

- Wipe Out—Falling off your surfboard while riding a wave. Accident while involved with surfing

Learning to surf

Many popular surfing destinations, such as Hawaii, California, Florida, Chile, Ireland, Australia and Costa Rica, have surf schools and surf camps that offer lessons. Surf camps for beginners and intermediates are multi-day lessons that focus on surfing fundamentals. They are designed to take new surfers and help them become proficient riders. All-inclusive surf camps offer overnight accommodations, meals, lessons and surfboards. Most surf lessons begin by instructors pushing students into waves on longboards. The longboard is considered the ideal surfboard for learning, due to the fact it has more paddling speed and stability than shorter boards. Funboards are also a popular shape for beginners as they combine the volume and stability of the longboard with the manageable size of a smaller surfboard.[3]

Typical surfing instruction is best performed one-on-one, but can also be done in a group setting. Popular surf locations such as Hawaii and Costa Rica offer perfect surfing conditions for beginners, as well as challenging breaks for advanced students. Surf spots more conducive to instruction typically offer conditions suitable for learning, most importantly, sand bars or sandy bottom breaks with consistent waves.

Surfing can be broken into several skills: drop in positioning to catch the wave, the pop-up, and positioning on the wave. Paddling out requires strength but also the mastery of techniques to break through oncoming waves (duck diving, eskimo roll). Drop in positioning requires experience at predicting the wave set and where they will break. The surfer must pop up quickly as soon as the wave starts pushing the board forward. Preferred positioning on the wave is determined by experience at reading wave features including where the wave is breaking.[4]

Balance plays a crucial role in standing on a surfboard. Thus, balance training exercises are a good preparation. Practicing with a Balance board or swing boarding helps novices master the art.

Equipment

Surfing can be done on various equipment, including surfboards, longboards, Stand Up Paddle boards (SUP's) , bodyboards, wave skis, skimboards, kneeboards and surf mats.

Surfboards were originally made of solid wood and were large and heavy (often up to 12 feet (3.7 m) long and 100 pounds (45 kg)). Lighter balsa wood surfboards (first made in the late 1940s and early 1950s) were a significant improvement, not only in portability, but also in increasing maneuverability.

Most modern surfboards are made of polyurethane foam (PU), with one or more wooden strips or "stringers", fiberglass cloth, and polyester resin. An emerging board material is epoxy (EPS) which is stronger and lighter than traditional fiberglass. Even newer designs incorporate materials such as carbon fiber and variable-flex composites.

Since epoxy surfboards are lighter, they will float better than a fiberglass board of similar size, shape and thickness. This makes them easier to paddle and faster in the water. However, a common complaint of EPS boards is that they do not provide as much feedback as a traditional fiberglass board. For this reason, many advanced surfers prefer that their surfboards be made from fiberglass.

Other equipment includes a leash (to stop the board from drifting away after a wipeout, and to prevent it from hitting other surfers), surf wax, traction pads (to keep a surfer's feet from slipping off the deck of the board), and fins (also known as skegs) which can either be permanently attached (glassed-on) or interchangeable.

Sportswear designed or particularly suitable for surfing may be sold as boardwear (the term is also used in snowboarding). In warmer climates, swimsuits, surf trunks or boardshorts are worn, and occasionally rash guards; in cold water surfers can opt to wear wetsuits, boots, hoods, and gloves to protect them against lower water temperatures. A newer introduction is a rash vest with a thin layer of titanium to provide maximum warmth without compromising mobility.

There are many different surfboard sizes, shapes, and designs in use today. Modern longboards, generally 9 to 10 feet (3.0 m) in length, are reminiscent of the earliest surfboards, but now benefit from modern innovations in surfboard shaping and fin design. Competitive longboard surfers need to be competent at traditional walking maneuvers, as well as the short-radius turns normally associated with shortboard surfing.

The modern shortboard began life in the late 1960s and has evolved into today's common thruster style, defined by its three fins, usually around 6 to 7 feet (1.8 to 2.1 m) in length. The thruster was invented by Australian shaper Simon Anderson.

Midsize boards, often called funboards, provide more maneuverability than a longboard, with more floation than a shortboard. While many surfers find that funboards live up to their name, providing the best of both surfing modes, others are critical.

- "It is the happy medium of mediocrity," writes Steven Kotler. "Funboard riders either have nothing left to prove or lack the skills to prove anything."[5]

There are also various niche styles, such as the Egg, a longboard-style short board targeted for people who want to ride a shortboard but need more paddle power. The Fish, a board which is typically shorter, flatter, and wider than a normal shortboard, often with a split tail (known as a swallow tail). The Fish often has two or four fins and is specifically designed for surfing smaller waves. For big waves there is the Gun, a long, thick board with a pointed nose and tail (known as a pin tail) specifically designed for big waves.

Famous surfing locations

Mavericks ( California )

Maverick's or Mavericks is a world-famous surfing location in Northern California. It is located approximately one-half mile (0.8 km) from shore in Pillar Point Harbor, just north of Half Moon Bay at the village of Princeton-By-The-Sea. After a strong winter storm in the northern Pacific Ocean, waves can routinely crest at over 25 feet (8m) and top out at over 50 feet (15m). The break is caused by an unusually-shaped underwater rock formation.

Mavericks is a winter destination for some of the world's best big wave surfers. Very few riders become big wave surfers; and of those, only a select few are willing to risk the hazardous conditions at Maverick's. An invitation-only contest is held there every winter, depending on wave conditions. The first big-wave surfing contest at Maverick's was held in 1999. The competition resulted in Darryl Virostko ("Flea"), Richard Schmidt, Ross Clarke-Jones, and Peter Mel taking first, second, third, and fourth places, respectively. The second competition was held the following year and put Darryl Virostko, Kelly Slater, Tony Ray, Peter Mel, Zach Wormhoudt, and Matt Ambrose in first through sixth places. In 2004, with Darryl Virostko, Matt Ambrose, Evan Slater, Anthony Tashnick, Peter Mel, and Grant Washburn placing in spots first through sixth. The 2005 winner was Anthony Tashnick. In 2006, Grant Baker, from South Africa, won first place, with Tyler Smith (Santa Cruz) and Brock Little (Hawai'i) in second and third places. The 2007 contest was called off by organizers because unusually mild weather resulted in no days with suitable waves by the end of March, the usual cutoff time for holding the competition. In 2008, Greg Long, from San Clemente, was crowned Maverick's Champion, Grant Baker (South Africa) won second place and Jamie Sterling (Hawai'i) won third place, followed by Tyler Smith in fourth, Grant Washburn in fifth, and Evan Slater in sixth. In 2010 South Africa's Chris Bertish took first place.

Dangers

Drowning

Surfing, like all water sports, carries the inherent danger of drowning. Although the board assists a surfer in staying buoyant, it cannot be relied on for floation, as it can be separated from the user.[6] The leash, which is attached at the ankle or knee, keeps the surfer connected to the board for convenience but does not prevent drowning. The established rule is that if the surfer cannot handle the water conditions without his or her board then he or she should not go in.

Some drownings have occurred as a result of leashes tangling with reefs, holding the surfer underwater. In very large waves such as Waimea or Mavericks, a leash may be undesirable, because the water can drag the board for long distances, holding the surfer underneath the wave.

Collisions

Under the wrong set of conditions, anything that a surfer's body can come in contact with is potentially a danger, including sand bars, rocks, reefs, surfboards, and other surfers.[7] Collisions with these objects can sometimes cause unconsciousness, or even death.

Many surfers jump off bridges, buildings, wharves and other structures to reach the surf. If the timing is wrong they can either damage themselves or their equipment, or both.[8]

A large number of injuries, up to 66%,[9] are caused by collision with a surfboard (nose or fins). Fins can cause deep lacerations and cuts, as well as bruising. While these injuries can be minor, they can open the skin to infection from the sea; groups like Surfers Against Sewage campaign for cleaner waters to reduce the risk of infections.

Falling off a surfboard, colliding with others, or hurting oneself whilst surfing is commonly referred to as a wipeout.

Marine life

Sea life can sometimes cause injuries and even fatalities. Animals such as sharks,[10] stingrays, seals and jellyfish can sometimes present a danger.[11]

Rip Currents

Riptides endanger both experienced and inexperienced surfers. Rip currents are water channels that flow away from shore. Since these currents lurk in seemingly calm waters, tired or inexperienced swimmers or surfers can easily be swept away.[12]

Seabed

The Seabed can pose dangers for the surfers. If a surfer is to fall while riding a wave, the wave will then toss him around, usually downwards. Whether it'd be a reef break or beach break, plenty of surfers have been seriously injured or even died because of the great collision with the bottom of the sea. Seabeds can get very shallow, especially, on beach breaks, during low tide. Take Cyclpos in Western Australia for example. This is one of the biggest and thickest reef breaks in the world, with waves measuring up to 10 meters high. Yet, the reef below is only about 2 meters deep.

See also

|

|

|

References

- ↑ History of Surfing Surfing for Life

- ↑ History of Surfing - Surf Naked

- ↑ John Dang. "Learn To Surf". surfscience.com. http://www.surfscience.com/topics/learn-to-surf/. Retrieved 2010-03-11.

- ↑ The quick guide on how to surf

- ↑ Kotler, Steven (June 13, 2006). West of Jesus: Surfing, Science, and the Origins of Belief. Bloomsbury. ISBN 1596910518.

- ↑ Ocean Safety

- ↑ Hard Bottom Surf Dangers

- ↑ citation needed

- ↑ The Dangers of Surfing

- ↑ http://www.sharkresearchcommittee.com/unprovoked_surfer.htm

- ↑ Surf Dangers Animals

- ↑ "Surfing's hidden dangers". BBC News. September 7, 2001. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/1530767.stm. Retrieved May 24, 2010.