Suppressor

.jpg)

A suppressor, sound suppressor, sound moderator, or silencer, is a device attached to or part of the barrel of a firearm to reduce the amount of noise and flash generated by firing the weapon.

It generally takes the form of a cylindrically shaped metal tube with various internal mechanisms to reduce the sound of firing by slowing the escaping propellant gas and sometimes by reducing the velocity of the bullet.[1][2]

Contents |

History

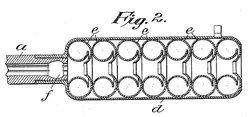

Early suppressors were created around the beginning of the 20th century by several inventors. American inventor Hiram Maxim is credited with inventing and selling the first commercially successful models circa 1902. Maxim gave his device the trademarked name Maxim Silencer. The muffler for internal combustion engines was developed in parallel with the firearm suppressor by Maxim in the early 20th century, using many of the same techniques to provide quieter-running engines. Indeed, in many European countries, automobile mufflers are still referred to as "silencers." The proper name Silencer has since fallen out of favor with some among the firearms industry, being replaced with the more literally accurate term sound suppressor or just suppressor, because a "sound supressor" does not "silence" any weapon, rather it eliminates muzzle flash and reduces the sonic pressure of a firearm discharging. Common usage and U.S. legislative language favor the historically earlier term, silencer. In U.S. law, the terms "firearm muffler" and "firearm silencer" are synonymous.[4]

Suppressors were regularly used by agents of the United States Office of Strategic Services, who favored the newly-designed High Standard HDM .22 Long Rifle pistol during World War II. OSS Director William Joseph "Wild Bill" Donovan demonstrated the pistol for President Franklin D. Roosevelt at the White House. According to OSS research chief Stanley Lovell,[5] Donovan (an old and trusted friend of the President) was waved into the Oval Office, where Roosevelt was dictating a letter. While Roosevelt finished his message, Donovan turned his back and fired ten shots into a sandbag he had brought with him, announced what he had done and handed the smoking gun to the astonished president.

Design and construction

The suppressor is typically a hollow cylindrical piece of machined metal (steel, aluminium, or titanium) containing expansion chambers that attaches to the muzzle of a pistol, submachine gun or rifle. These "can"-type suppressors (so-called as they resemble a beverage can), may be detached by the user and attached to a different firearm of the same caliber. Another type is the "integral" suppressor, which consists of expansion chambers surrounding the barrel. The barrel is pierced with openings or "ports" which bleed off gases into the chambers. This type of suppressor is part of the firearm, and maintenance of the suppressor requires that the firearm be at least partially disassembled.

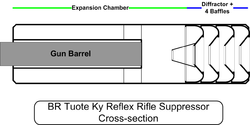

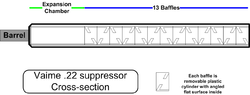

Both types of suppressor reduce noise by allowing the rapidly expanding gases from the firing of the cartridge to be briefly diverted or trapped inside a series of hollow chambers. The trapped gas expands and cools, and its pressure and velocity decreases as it exits the suppressor. The chambers are divided by either baffles or wipes (see below). There are typically at least four and up to perhaps fifteen chambers in a suppressor, depending on the intended use and design details. Often, a single, larger expansion chamber is located at the muzzle end of a can-type suppressor, which allows the propellant gas to expand considerably and slow down before it encounters the baffles or wipes. This larger chamber may be "reflexed" toward the rear of the barrel to minimize the overall length of the combined firearm and suppressor, especially with longer weapons such as rifles.

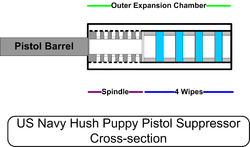

Suppressors vary greatly in size and efficiency. One disposable type developed in the 1980s by the U.S. Navy for 9 mm pistols was 150 mm (5.9 in) long and 45 mm (1.8 in) in outside diameter, and was designed for six shots with standard ammunition or up to thirty shots with subsonic (slower than the speed of sound) ammunition. In contrast, one suppressor designed for rifles firing the powerful .50 caliber cartridge is 509 mm (20 in) long and 76 mm (3 in) in diameter.[6]

Components

Baffles are usually circular metal dividers which separate the expansion chambers. Each baffle has a hole in its center to permit the passage of the bullet through the suppressor and towards the target. The hole is typically at least 0.04 inch (1 mm) larger than the bullet caliber to minimize the risk of the bullet hitting the baffle ("baffle strike"). Baffles are typically made of stainless steel, aluminium, titanium or alloys such as Inconel, and are either machined out of solid metal or stamped out of sheet metal. A few suppressors for low-powered cartridges such as the .22 Long Rifle have successfully used plastic baffles (certain models by Vaime and others.)[1]

Baffles are separated by spacers, which keep them aligned at a specified distance apart inside the suppressor. Many baffles are manufactured as a single assembly with its spacer, and several suppressor designs have all the baffles attached together with spacers as a one-piece helical baffle stack. Modern baffles are usually carefully shaped to divert the propellant gases effectively into the chambers. This shaping can be a slanted flat surface, canted at an angle to the bore, or a conical or otherwise curved surface. One popular technique is to have alternating angled surfaces through the stack of baffles.

Baffles come in several designs. M, K, Z, and Ω(Omega) are the most prevalent. M-type is the crudest and composes an inverted cone. K forms slanted obstructions diverging from the sidewalls, creating turbulence across the boreline. Z is expensive to machine and includes "pockets" of dead airspace along the sidewalls which trap expanded gasses and hold them thereby lenghtening the time that the gasses cool before exiting. Omega is an advanced design combining elements of all three previous designs. Omega forms a series of spaced cones drawing gas away from the boreline, incorporates a scallopped mouth creating cross-bore turbulence, which is in turn directed to a "mouse-hole" opening between the baffle stack and sidewall.

Baffles usually last for a significant number of firings. Propellant gas heats and erodes the baffles, causing wear, which is worsened by high rates of fire. Aluminium baffles are seldom used with fully automatic weapons, because service life is unacceptably short. Some modern suppressors using steel or high-temperature alloy baffles can endure extended periods of fully-automatic fire without damage. The highest-quality rifle suppressors available today have a claimed service life of greater than 30,000 rounds.[1]

Wipes are inner dividers intended to touch the bullet as it passes through the suppressor, and are typically made of rubber, plastic or foam. Each wipe may either have a hole drilled in it before use, a pattern stamped into its surface at the point where the bullet will strike it, or it may simply be punched through by the bullet. Wipes typically last for a small number of firings (perhaps no more than five) before their performance is significantly degraded. While many suppressors used wipes in the Vietnam War era, most modern suppressors do not use them to minimize disassembly and parts replacement.

"Wet" suppressors or "wet cans" use a small quantity of water, oil, grease or gel in the expansion chambers to cool the propellant gases and reduce their volume (see ideal gas law). The coolant lasts only a few shots before it must be replenished, but can greatly increase the effectiveness of the suppressor. Water is most effective, due to its high heat of vaporization, but it can run or evaporate out of the suppressor. Grease, while messier and less effective than water, can be left in the suppressor indefinitely without losing effectiveness. Oil is the least effective and least preferable, as it runs while being as messy as grease, and leaves behind a fine mist of aerosolized oil after each shot. Water-based gels, such as wire-pulling lubricant gel, are a good compromise; they offer the efficacy of water with less mess, as they do not run or drip. However, they take longer to apply, as they must be cleared from the bore of the suppressor to ensure a clear path for the bullet (grease requires this step as well). Generally, only pistol suppressors are shot wet, as rifle suppressors handle such high pressure and heat that the liquid is gone within 1-3 shots. Many manufacturers will not warranty their rifle suppressors for "wet" fire, as some feel this may even result in a dangerous over-pressurization of the silencer.

Packing materials such as metal mesh, steel wool or metal washers may be used to fill the chambers and further dissipate and cool the gases. These are somewhat more effective than empty chambers, but less effective than wet designs.[1] Metal mesh, if properly used, may last for hundreds or thousands of shots of spaced semi-automatic fire, however steel wool usually degrades within ten shots with stainless wool lasting longer than regular steel wool. Like wipes, packing materials are rarely found in modern suppressors.

Wipes, packing materials and purpose-designed wet cans have been generally abandoned in 21st-century suppressor design because they decrease overall accuracy and require excessive cleaning and maintenance. The instructions from several manufacturers state that their suppressors need not be cleaned at all. Furthermore, legal changes in the United States during the 1980s and 1990s made it much more difficult for end-users to legally replace internal silencer parts, and the newer designs reflect this reality.

Advanced types

In addition to containing and slowly releasing the gas pressure associated with muzzle blast or reducing pressure through the use of coolant mediums, advanced suppressor designs attempt to modify the properties of the sound waves generated by the muzzle blast. In these designs, effects known as frequency shifting and phase cancellation (or destructive interference) are used in an attempt to make the suppressor quieter. These effects are achieved by separating the flow of gases and causing them to collide with each other or by venting them through precision-made holes. The intended effect of frequency shifting is to shift audible sound waves frequencies into ultrasound (above 20 kHz), beyond the range of human hearing. The Russian AN-94 assault rifle features a muzzle attachment that claims apparent noise reduction by venting some gases through a "dog-whistle" type channel. Phase cancellation occurs when similar sound wave frequencies encounter each other 180° out of phase, canceling the amplitude of the wave and eliminating the pressure variations perceived as sound.

Using either property to advantage requires that the suppressor be designed within the specification of the muzzle blast in mind. For example, the velocity of the sound waves is a major factor. This figure can change significantly between different cartridges and barrel lengths.

Thus, in order for maximum effectiveness to be achieved, the suppressor must be "tuned" for a specific cartridge/barrel length combination. This can be done through the use of either a fixed or adjustable baffle design. While it may sound daunting, any weapon that needs to provide such exceptional sound suppression is almost certainly going to be manufactured in small quantities and issued only for mission profiles critical enough to make such efforts worthwhile.

However, these concepts are controversial because muzzle blast creates broadband noise rather than pure tones, and phase cancellation in particular is therefore extremely difficult (if not impossible) to achieve. Some suppressor manufacturers claim to use phase cancellation in their designs, but these claims are generally unsupported from a scientific perspective.

From the practical perspective, supersonic cartridge loads are impractical to suppress past the levels that are merely hearing-safe for the shooter due to the sonic boom emitted by the bullet, and cartridges such as .22LR and .45ACP have long been recognized as easy to suppress even if using technology dating back to 1940s when the mission calls for the quietest gun available.

Sources of firearm noise

The portrayal of suppressed firearms in popular culture is not always accurate and could lead to the misconception that silencers are capable of completely eliminating the sound of firing, or reducing it to a quiet whistling or "phut" sound. This is because when a gun is fired, multiple sounds are possibly made. There are five major categories of suppressed fire noise: action, blast, sonic signature, impact, and operator. Some of these are present in all instances, others depend wholly on the specific mechanics of the weapon employed.

In order of timing:

- Action noise required to ignite the round.

- Muzzle blast resulting from the discharge of propellant from the end of the barrel.

- Sonic signature of the projectile in flight (supersonic velocity rounds).

- Action noise in some firearm variants as the spent round is discharged and a fresh round reloaded.

- Impact noise created as the projectile finds terminal impact.

Obviously, some of these sounds are much louder than others. The two loudest sounds in a gunshot are typically the muzzle blast and the sonic signature. Multiple techniques are used to address each of these sounds, but the suppressor itself is capable of addressing muzzle blast, sonic signature (through integral gas bleed, reducing the projectile to subsonic) and the ability to cancel the mechanical action noise through Nielsen device manipulation, canceling the ejection cycle.

Real world data

Live tests by independent reviewers of numerous commercially available suppressors find that even low caliber unsuppressed .22 LR firearms produce gunshots over 160 decibels.[7] In testing, most of the suppressors reduced the volume to between 130 and 145 dB, with the quietest suppressors metering at 117 dB. The actual suppression of sound ranged from 14.3 to 43 dB, with most data points around the 30 dB mark.

Comparatively, ear protection commonly used while shooting provides 18 to 32 dB of sound reduction at the ear.[8] Further, chainsaws, rock concerts, rocket engines, pneumatic drills, small firecrackers, and ambulance sirens are rated at 100 to 140 dB.[9]

While some consider the noise reduction of a suppressor significant enough to permit safe shooting without hearing protection ("hearing safe"), noise induced hearing loss occurs at 85 dB or above,[10] and suppressed gunshots regularly meter above 130 dB. However, the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration uses 140 dB as the "safety cutoff" for impulsive noise, which has led most US manufacturers to advertise sub-140 dB suppressors as "hearing safe."

Limitations of dB meter effectiveness

dB testing measures only the peak sound "pressure" noise, not duration or frequency. Limitations of dB testing become apparent in a comparison of sound between a .308 caliber rifle and a .300 Winchester Magnum rifle. The dB meter will show that both rifles produce the same decibel level of noise. Upon firing these rifles, however, it is clear that the .300 WIN MAG sounds much louder. What the decibel meter doesn't show is that although both rifles produce the same peak sound pressure level (SPL), the .300 WIN MAG holds its peak duration longer. The .300 WIN MAG sound remains at full value longer and is louder while the .308 goes to peak and falls off more quickly. dB meters fail in this and other regards when being used as the principal means to determine suppressor capability.[11]

Caliber versus volume

The caliber and power of the bullet/cartridge being suppressed is also an important factor. Generally, equal quality suppressors can quiet the report of a smaller caliber bullet more effectively than a larger caliber bullet. This is because the exhaust gases can move more quickly through the exit hole necessary for larger caliber bullets. Likewise, cartridges which produce higher pressures and more gasses, such as those used in rifles, will also generally be louder than those which produce less pressure and fewer gasses, such as handgun cartridges. In a gunshot, the sound of the report (the combination of the sonic boom, the vacuum release, and burn of powder) will almost always be louder than the sound of the action cycling of an auto-loading firearm. Alan C. Paulson, a renowned firearms specialist, claimed to have encountered an integrally suppressed .22 LR that had such a quiet report,[12] although this is somewhat uncommon.

Because of the limited stopping power of less powerful cartridges[13], movie scenes in which an attacker fires a near-silent shot that instantly kills the victim are generally unrealistic.

Subsonic ammunition versus volume

In weapons firing supersonic bullets, the supersonic bullet itself produces a loud and very sharp sound as it leaves the muzzle in excess of the speed of sound and gradually reducing speed as it travels downrange. This is a small sonic boom, and is referred to in the firearm field as "ballistic crack". Subsonic ammunition reduces this sound, but at the cost of lower velocity, often resulting in decreased range and effectiveness on the target. Military marksmen and police units may use this ammunition to maximize the effectiveness of their silenced rifles. While the range may be decreased when using subsonic rounds, this may be acceptable for specialized situations, where the absolute minimum amount of noise is required.[14]

However, the numeric effectiveness of subsonic rounds is, again, misrepresented by media. Independent testing of commercially available firearm suppressors with commercially available subsonic rounds has found that .308 subsonic rounds decreased the volume at the muzzle 10 to 12 dB when compared to the same caliber of suppressed supersonic ammunition.[7] When combined with suppressors, the subsonic .308 rounds metered between 121 and 137 dB.

This ballistic crack depends on the speed of sound, which in turn depends mainly on air temperature. At sea level, an ambient temperature of 70 °F (21 °C), and under normal atmospheric conditions, the speed of sound is approximately 1140 feet per second (347 m/s). Bullets that travel near the speed of sound are considered transonic, which means that the airflow over the surface of the bullet, which at points travels faster than the bullet itself, can break the speed of sound. Pointed bullets which gradually displace air can get closer to the speed of sound than round nosed bullets before becoming transonic.

Because merely reducing the propellant in a cartridge to get a slower bullet would lead to less stopping power, special cartridges have been developed specifically to maximize the energy available when used with a suppressor. These cartridges use very heavy bullets to make up for the energy lost by keeping the bullet subsonic. A good example of this is the .300 Whisper cartridge, which is formed from a necked-up .221 Remington Fireball cartridge case. The subsonic .300 Whisper fires up to a 250 grain (16.2 g), .30 caliber bullet at about 980 feet per second (298 m/s), generating about 533 ft·lbf (722 J) of energy at the muzzle. While this is similar to the energy available from the .45 ACP pistol cartridge, the reduced diameter and streamlined shape of the heavy .30 caliber bullet provides far better external ballistic performance, improving range substantially.

9x19mm Parabellum, a very popular caliber for suppressed shooting, can use almost any factory-loaded 147 gr (9.5 g) weight round to achieve subsonic performance. These 147 gr weight bullets typically have a velocity between 900 and 980 feet per second (275 and 300 m/s), which is less than the common 1140 ft/s speed of sound.

Russian 9x39mm ammo had a high subsonic Ballistic coefficient, high retained downrange energy, high Sectional density, and moderate recoil. All elements combined make this a very attractive choice for Close Quarters Combat firearms.

Instead of using subsonic ammunition, one can also lower the muzzle velocity of a supersonic bullet before it leaves the barrel. Some suppressor designs, referred to as "integrals", do this by allowing gas to bleed off along the length of the barrel before the projectile exits. However, as of 2010, the best-known weapons with integral suppressors such as MP5SD and VSS Vintorez/AS Val fire subsonic cartiges and use integral suppressors for the sole purpose of reducing the weapon's length rather than to slow down an inherently supersonic cartridge.

Identification

Aside reductions in volume, suppressors also tend to alter the sound to something that is not identifiable as a gunshot. This reduces or eliminates attention drawn to the shooter (hence the Finnish expression: "A silencer does not make a marksman silent, but it does make him invisible"). This is especially true in cases where there are other sources of ambient noise, such as in an urban environment. Suppressors are particularly useful in enclosed spaces where the sound, flash and pressure effects of a weapon being fired are amplified. Such effects may disorient the shooter, affecting situational awareness, concentration and accuracy, and can permanently damage hearing very quickly.

As the suppressed sound of firing is overshadowed by ballistic crack, observers can be deceived as to the location of the shooter, often from 90 to 180 degrees from his actual location. However, counter-sniper tactics can include Gunshot Location Detection Systems, where sensitive microphones are coupled to computer algorithms, and use the ballistic crack to detect and localize the origin of the shot. The U.S. Boomerang system is currently the only deployed example.

Rear of a suppressor with the Nielsen device protruding (completely assembled). |

Retaining ring unscrewed and Nielsen device partially removed. |

Nielsen device completely removed and disassembled. |

Rear of suppressor showing the rotational indexing system incorporated into some Nielsen devices. |

Other advantages

There are many advantages in using a suppressor that are not related to the sound.

Hunters using centerfire rifles find suppressors bring various important benefits that outweigh the extra weight and resulting change in the firearm's center of gravity. The most important advantage of a suppressor is the hearing protection for the shooter as well as his/her companions. There are many hunters who have suffered permanent hearing damage due to someone else firing a high-caliber gun too closely without a warning. By reducing noise, recoil and muzzle-blast, it also enables the firer to follow-through calmly on his first shot and fire a further carefully-aimed shot without delay if necessary. Wildlife of all kinds are often confused as to the direction of the source of a well-suppressed shot. In the field, however, the comparatively large size of a centerfire rifle suppressor can cause unwanted noise if it bumps or rubs against vegetation or rocks, and many users cover them with neoprene sleeves.

Suppressors can increase the precision of a rifle, as they strip away hot gases from around the projectile in a uniform fashion. The suppressor can reduce the recoil significantly as it traps the escaping gas. This gas mass is a little less than one-half the projectile mass (approximately 1.6 grams vs 4 grams for 5.56x45mm NATO ammunition), with the gas exiting the muzzle at about twice the projectile's velocity, thus giving a reduction in the felt recoil of approximately 15%.[1] The added weight of the suppressor — normally 300 to 500 grams — also contributes to the reduction of the recoil, though a significantly heavy suppressor would unbalance a weapon. Further, the pressure against the face of each baffle is higher than the pressure on its reverse side, making each baffle a miniature "pneumatic ram" which pulls the suppressor forward on the weapon, which can contribute an immense force to counter recoil.

A suppressor also cools the hot gases coming out of the barrel enough that most of the lead laced vapor that leaves the barrel condenses inside the suppressor, reducing the amount of lead that might be inhaled by the shooter and others around them. However, this might be offset by increased back pressure which results in hot gas blowing back into a shooter's face.

Regulation

Legal regulation of suppressors varies widely around the world. In some nations, such as Finland, Norway and France, some or all types of suppressor are essentially unregulated and may be bought "over the counter" in retail stores or by mail-order as they are considered a great help, along with hearing protection, to preserve the hearing of the user and any onlookers.

Asia

In Thailand, sound suppressors of any kind are allowed to be used only by law enforcement units or military personnel in operation.

In Hong Kong, "any accessory to such arms designed or adapted to diminish the noise or flash" is within the definition of 'arms' under the Firearms and Ammunition Ordinance (HK Laws. Chap 238). As such, a permit is required (as with firearms and ammunition) for possession which would otherwise be illegal and carries penalties up to a fine of HK$100,000 and 14 years in jail.

Europe

In Austria, the purchase or possession of a suppressor is prohibited according to §17 of the Austrian Weapons Law.

In Norway, suppressors can be bought by anyone possessing a simple firearm license.

In Denmark, the Danish Weapons And Explosives Law makes the unlicensed possession of a suppressor illegal. A permit may be acquired from the local police, but permission is almost always denied. Only police and hunters with special permission for the emergency slaughtering of livestock inside buildings are allowed to use them.

Italy prohibits the purchase or possession of a suppressor except for military personnel.

In Sweden, suppressors for specified calibers are legal for hunting purposes. A license is required, but is normally always granted.

In Finland, suppressors are not classified as "weapon parts". Therefore, they are completely legal in all calibers, requiring no registration or permit. As a somewhat generalized rule of thumb, Finnish gun law classifies only parts subject to firing pressure directly involved with firing the cartridge as weapon parts; barrels, bolts, and any part with a chamber. These are restricted to owners with a valid permit. All other parts and accessories are not weapon parts under this classification. This would include parts like magazines, various sights and scopes, and also suppressors.

In Poland, suppressors are not classified as "important weapon parts". Therefore, they are completely legal in all calibers, requiring no registration or permit. However using suppressors (even installing) with firearm is prohibited. Only police and military are allowed to use them.

In the United Kingdom, sales of suppressors fall into four categories of use. For replica and air weapons, the purchase of a suppressor requires no license and in most cases, no identification requirement. For shotguns, these will probably require the presentation of the buyer's shotgun certificate but will not be recorded. For a small- or full-bore rifle, the firearm certificate (FAC) will need to show permission for the purchase of a suppressor and also the gun for which it is intended. All firearms certificates have the firearm and caliber approved by the police and annotated to the document before a suppressor may be purchased. Police forces usually approve applications for a suppressor for hunting and target shooters, as the risks of litigation for personal injury, especially high-tone deafness resulting from shooting-induced hearing loss, are significant; and noise pollution in general is a problem for shooting sports.

In the Netherlands suppressors are only legal if used for airguns. All other civilian use and ownership is prohibited by law.

In Turkey, civilian purchase, sale or possession of suppressors are strictly prohibited, with possible jail terms of up to 25 years if convicted. Suppressors can only be purchased by military personnel when approved by the officer in charge of the base armory. Individual law enforcement officers are not eligible to purchase or possess suppressors unless these are issued by a local agency, in which case these would be registered to the General Directorate of Security in Ankara.

North America

In Canada, a device to muffle or stop the sound of a firearm is a "prohibited device" under the Criminal Code.[15] A prohibited device is not inherently illegal in Canada but it does require an uncommon and very specific prohibited device license for its possession, use, and transport. Suppressors cannot be imported into the country by civilians[16]; special licensing is required for businesses to import and sell suppressors, and they are typically only available to law enforcement, conservation agencies and the military.

The United States taxes and strictly regulates the manufacture and sale of suppressors under the National Firearms Act. They are legal for individuals to possess and use for lawful purposes in thirty-eight of the fifty states.[17] However, a prospective user must go through an application process administered by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), which requires a Federal tax payment of USD 200.00 and a thorough criminal background check. The USD 200.00 buys a tax stamp, which is the legal document allowing possession of a suppressor. The market for used suppressors in the U.S. is consequently very poor, which has driven innovations in the field (buyers want the height of technology, because they are basically "stuck" with the purchase). Primitive suppressors are available in other countries for under USD 40,[18] but they are usually of crude construction, using cheap materials and baffle designs that were obsolete in the United States by the 1970s. While suppressors in the US are more expensive (hundreds to thousands of dollars), they are generally built with highly advanced baffle stacks and exotic materials like Inconel and high-grade heat-treated stainless steels. The following states have explicitly banned any civilian from possessing a suppressor: California, Delaware, District of Columbia, Hawaii, Illinois, Iowa, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont.

The Federal legal requirements to manufacture a suppressor in the United States are enumerated in Title 26, Chapter 53 of the United States Code.[19] The individual states and several municipalities also have their specific requirements.

Oceania

Suppressors are banned in all Australia's states.

New Zealand has no restrictions on the manufacture, sale, possession, or use of suppressors.

Naming

While suppressors are also referred to as "silencers", the latter is misleading because no firearm can be made completely silent, as the term "silencer" implies[1]. Functionally, a suppressor is meant to diminish the report of a discharged round, or make its sound unrecognizable. Other sounds emanating from the weapon remain unchanged. Even subsonic bullets make distinct sounds by their passage through the air and striking targets, and supersonic bullets produce a small sonic boom, resulting in a "ballistic crack". Semi- and fully-automatic firearms also make distinct noises as their actions cycle, ejecting the fired cartridge case and loading a new round. Despite being misleading, the term "silencer" is still a wide-spread, even official term.

Both the United States Department of Justice and the BATF (Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms) refers to these devices as "silencers".[20]

See also

- OTs-38 Stechkin silent revolver

- Sound Blimp

- Title II weapons

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Paulson, Alan C (1996). Silencer History and Performance, Vol 1: Sporting And Tactical Silencers. Paladin Press. ISBN 0873649095.

- ↑ Paulson, Alan C; Kokalis, Peter G., and Parker, N.R. (2002). Silencer History and Performance, Vol 2: CQB, Assault Rifle, and Sniper Technology. Paladin Press. ISBN 1-58160-323-1.

- ↑ Parker, Firearm Suppressor Patents: Vol. 1 United States Patents, ISBN 1-58160-460-2

- ↑ "Title 18, United States Code, Chapter 44, Section (§) 921 (a)(3)(C) - Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School". Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School. 1994-09-13. http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/18/usc_sec_18_00000921----000-.html. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ↑ Stanley Lovell, Of Spies and Stratagems, 1963.

- ↑ "Reflex Suppressor for Barrett M82A1 - BR Reflex Suppressors (Finland)". Guns.connect.fi. http://www.guns.connect.fi/rs/btxgraaf.html. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Silvers, Robert (2005). "Results". http://silencertalk.com/results.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ↑ "Firearms and Hearing Protection | March 2007 | The Hearing Industry Resource". Hearingreview.com. 2007-02-12. http://www.hearingreview.com/issues/articles/2007-03_06.asp. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ↑ "2.7: Decibels". Campus.murraystate.edu. http://campus.murraystate.edu/tsm/tsm118/Ch2/Ch2_7/Ch2_7.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ↑ "nihl". Hearinglossweb.com. http://www.hearinglossweb.com/Medical/Causes/nihl/nihlfs.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ↑ dB in Principle and Practice, AWC Systems Technology April 2010

- ↑ Silencer: History and Performance, Volume 1 by Alan C. Paulson

- ↑ http://www.abaris.net/info/ballistics/hatcher-table.htm

- ↑ ""Modern sniper rifles"". world.guns.ru. 2001-01-26. http://world.guns.ru/sniper/sn00-e.htm. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ↑ "Criminal Code of Canada, Part III Firearms and other Weapons". http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/showdoc/cs/C-46/bo-ga:l_III//en#anchorbo-ga:l_III. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ "Importing a Firearm or Weapon Into Canada". Canadian Border Services Agency. http://www.cbsa-asfc.gc.ca/publications/pub/bsf5044-eng.html. Retrieved 2008-06-11.

- ↑ "NFA Gun Trust Lawyer Blog". http://www.guntrustlawyer.com. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ "Husssh Sound Moderators". Husssh.co.nz. http://www.husssh.co.nz/details.html. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ↑ "Title 26, United States Code, Chapter 53 - Legal Information Institute, Cornell University Law School". Law.cornell.edu. 2008-09-24. http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/html/uscode26/usc_sup_01_26_10_E_20_53.html. Retrieved 2009-03-09.

- ↑ "Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, Silencer FAQ". http://www.atf.gov/firearms/nfa/041708silencer_faqs.htm. Retrieved 2009-11-14.