Breastfeeding

- Suckling and nursing are synonyms. For other uses, see Nursing (disambiguation) and Suckling (disambiguation)

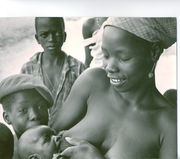

Breastfeeding is the feeding of an infant or young child with breast milk directly from female human breasts (i.e., via lactation) rather than from a baby bottle or other container. Babies have a sucking reflex that enables them to suck and swallow milk. Most mothers can breastfeed for six months or more, without the addition of infant formula or solid food.

Human breast milk is the healthiest form of milk for human babies.[1] There are few exceptions, such as when the mother is taking certain drugs or is infected with Human T-lymphotropic virus, HIV, or has active untreated tuberculosis. Breastfeeding promotes health, helps to prevent disease, and reduces health care and feeding costs.[2][3][4] Artificial feeding is associated with more deaths from diarrhea in infants in both developing and developed countries.[5] Experts agree that breastfeeding is beneficial, but may disagree about the length of breastfeeding that is most beneficial, and about the risks of using artificial formulas.[6][7][8]

The World Health Organization (WHO) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) emphasize the value of breastfeeding for mothers as well as children. Both recommend exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life and then supplemented breastfeeding for at least one year and up to two years or more.[9][10] While recognizing the superiority of breastfeeding, regulating authorities also work to minimize the risks of artificial feeding.[7]

Breast milk

Not all the properties of breast milk are understood, but its nutrient content is relatively stable. Breast milk is made from nutrients in the mother's bloodstream and bodily stores. Breast milk has just the right amount of fat, sugar, water, and protein that is needed for a baby's growth and development.[11] Because breastfeeding uses an average of 500 calories a day it helps the mother lose weight after giving birth.[12] The composition of breast milk changes depending on how long the baby nurses at each session, as well as on the age of the child. The quality of a mother's breast milk may be compromised by smoking, alcoholic beverages, caffeinated drinks, marijuana, methamphetamine, heroin, and methadone.[13]

Benefits for the infant

Scientific research, such as the studies summarized in a 2007 review for the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)[14] and a 2007 review for the WHO[15], has found many benefits to breastfeeding for the infant. These include:

Greater immune health

During breastfeeding antibodies pass to the baby[16]. This is one of the most important features of colostrum, the breast milk created for newborns. Breast milk contains several anti-infective factors such as bile salt stimulated lipase (protecting against amoebic infections), lactoferrin (which binds to iron and inhibits the growth of intestinal bacteria)[17][18] and immunoglobulin A protecting against microorganisms.[19]

Fewer infections

Among the studies showing that breastfed infants have a lower risk of infection than non-breastfed infants are:

- In a 1993 University of Texas Medical Branch study, a longer period of breastfeeding was associated with a shorter duration of some middle ear infections (otitis media with effusion) in the first two years of life.[20]

- A 1995 study of 87 infants found that breastfed babies had half the incidence of diarrheal illness, 19% fewer cases of any otitis media infection, and 80% fewer prolonged cases of otitis media than formula fed babies in the first twelve months of life.[21]

- Breastfeeding appeared to reduce symptoms of upper respiratory tract infections in premature infants up to seven months after release from hospital in a 2002 study of 39 infants.[22]

- A 2004 case-control study found that breastfeeding reduced the risk of acquiring urinary tract infections in infants up to seven months of age, with the protection strongest immediately after birth.[23]

- The 2007 review for AHRQ found that breastfeeding reduced the risk of acute otitis media, non-specific gastroenteritis, and severe lower respiratory tract infections.[14]

Protection from SIDS

Breastfed babies have better arousal from sleep at 2–3 months. This coincides with the peak incidence of sudden infant death syndrome.[24] A study conducted at the University of Münster found that breastfeeding halved the risk of sudden infant death syndrome in children up to the age of 1.[25]

Higher intelligence

Studies examining whether breastfeeding in infants is associated with higher intelligence later in life include:

- Horwood, Darlow and Mogridge (2001) tested the intelligence quotient (IQ) scores of 280 low birthweight children at seven or eight years of age.[26] Those who were breastfed for more than eight months had verbal IQ scores 6 points higher (which was significantly higher) than comparable children breastfed for less time.[26] They concluded "These findings add to a growing body of evidence to suggest that breast milk feeding may have small long term benefits for child cognitive development."[26]

- A 2005 study using data on 2,734 sibling pairs from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health "provide[d] persuasive evidence of a causal connection between breastfeeding and intelligence." The same data "also suggests that nonexperimental studies of breastfeeding overstate some of [breastfeeding's] other long-term benefits, even if controls are included for race, ethnicity, income, and education." [27]

- In 2006, Der and colleagues, having performed a prospective cohort study, sibling pairs analysis, and meta-analysis, concluded that "Breast feeding has little or no effect on intelligence in children."[28] The researchers found that "Most of the observed association between breast feeding and cognitive development is the result of confounding by maternal intelligence."[28]

- The 2007 review for the AHRQ found "no relationship between breastfeeding in term infants and cognitive performance."[14]

- The 2007 review for the WHO "suggests that breastfeeding is associated with increased cognitive development in childhood." The review also states that "The issue remains of whether the association is related to the properties of breastmilk itself, or whether breastfeeding enhances the bonding between mother and child, and thus contributes to intellectual development." [15]

- Two initial cohort studies published in 2007 suggest babies with a specific version of the FADS2 gene demonstrated an IQ averaging 7 points higher if breastfed, compared with babies with a less common version of the gene who showed no improvement when breastfed.[29] FADS2 affects the metabolism of polyunsaturated fatty acids found in human breast milk, such as docosahexaenoic acid and arachidonic acid, which are known to be linked to early brain development.[29] The researchers were quoted as saying "Our findings support the idea that the nutritional content of breast milk accounts for the differences seen in human IQ. But it's not a simple all-or-none connection: it depends to some extent on the genetic makeup of each infant."[30] The researchers wrote "further investigation to replicate and explain this specific gene–environment interaction is warranted."[29]

- In "the largest randomized trial ever conducted in the area of human lactation," between 1996 and 1997 maternity hospitals and polyclinics in Belarus were randomized to receive or not receive breastfeeding promotion modeled on the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative.[31] Of 13,889 infants born at these hospitals and polyclinics and followed up in 2002-2005, those who had been born in hospitals and polyclinics receiving breastfeeding promotion had IQs that were 2.9-7.5 points higher (which was significantly higher).[31] Since (among other reasons) a randomized trial should control for maternal IQ, the authors concluded in a 2008 paper that the data "provide strong evidence that prolonged and exclusive breastfeeding improves children's cognitive development."[31]

Less diabetes

Infants exclusively breastfed have less chance of developing diabetes mellitus type 1 than peers with a shorter duration of breastfeeding and an earlier exposure to cow milk and solid foods.[14][32] Breastfeeding also appears to protect against diabetes mellitus type 2,[14][15][33][34] at least in part due to its effects on the child's weight.[34]

Less childhood obesity

Breastfeeding appears to reduce the risk of extreme obesity in children aged 39 to 42 months.[35] The protective effect of breastfeeding against obesity is consistent, though small, across many studies, and appears to increase with the duration of breastfeeding.[14][15][36]

Less tendency to develop allergic diseases (atopy)

In children who are at risk for developing allergic diseases (defined as at least one parent or sibling having atopy), atopic syndrome can be prevented or delayed through exclusive breastfeeding for four months, though these benefits may not be present after four months of age.[37] However, the key factor may be the age at which non-breastmilk is introduced rather than duration of breastfeeding.[38] Atopic dermatitis, the most common form of eczema, can be reduced through exclusive breastfeeding beyond 12 weeks in individuals with a family history of atopy, but when breastfeeding beyond 12 weeks is combined with other foods incidents of eczema rise irrespective of family history.[39]

Less necrotizing enterocolitis in premature infants

Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is an acute inflammatory disease in the intestines of infants. Necrosis or death of intestinal tissue may follow. It is mainly found in premature births. In one study of 926 preterm infants, NEC developed in 51 infants (5.5%). The death rate from necrotizing enterocolitis was 26%. NEC was found to be six to ten times more common in infants fed formula exclusively, and three times more common in infants fed a mixture of breast milk and formula, compared with exclusive breastfeeding. In infants born at more than 30 weeks, NEC was twenty times more common in infants fed exclusively on formula.[40] A 2007 meta-analysis of four randomized controlled trials found "a marginally statistically significant association" between breastfeeding and a reduction in the risk of NEC.[14]

Other long term health effects

In one study, breastfeeding did not appear to offer protection against allergies.[41] However, another study showed breastfeeding to have lowered the risk of asthma, protect against allergies, and provide improved protection for babies against respiratory and intestinal infections.[42]

A review of the association between breastfeeding and celiac disease (CD) concluded that breast feeding while introducing gluten to the diet reduced the risk of CD. The study was unable to determine if breastfeeding merely delayed symptoms or offered life-long protection.[43]

An initial study at the University of Wisconsin found that women who were breast fed in infancy may have a lower risk of developing breast cancer than those who were not breast fed.[44]

Breastfeeding may decrease the risk of cardiovascular disease in later life, as indicated by lower cholesterol and C-reactive protein levels in adult women who had been breastfed as infants.[15][45] Although a 2001 study suggested that adults who had been breastfed as infants had lower arterial distensibility than adults who had not been breastfed as infants[46], the 2007 review for the WHO concluded that breastfed infants "experienced lower mean blood pressure" later in life[15]. Nevertheless, the 2007 review for the AHRQ found that "the relationship between breastfeeding and cardiovascular diseases was unclear"[14].

Benefits for mothers

Breastfeeding is a cost effective way of feeding an infant, providing nourishment for a child at a small cost to the mother. Frequent and exclusive breastfeeding can delay the return of fertility through lactational amenorrhea, though breastfeeding is an imperfect means of birth control. During breastfeeding beneficial hormones are released into the mother's body[16] and the maternal bond can be strengthened.[11] Breastfeeding is possible throughout pregnancy, but generally milk production will be reduced at some point.[47]

Bonding

Hormones released during breastfeeding help to strengthen the maternal bond.[11] Teaching partners how to manage common difficulties is associated with higher breastfeeding rates.[48] Support for a mother while breastfeeding can assist in familial bonds and help build a paternal bond between father and child.[49]

If the mother is away, an alternative caregiver may be able to feed the baby with expressed breast milk. The various breast pumps available for sale and rent help working mothers to feed their babies breast milk for as long as they want. To be successful, the mother must produce and store enough milk to feed the child for the time she is away, and the feeding caregiver must be comfortable in handling breast milk.

Hormone release

Breastfeeding releases oxytocin and prolactin, hormones that relax the mother and make her feel more nurturing toward her baby.[50] Breastfeeding soon after giving birth increases the mother's oxytocin levels, making her uterus contract more quickly and reducing bleeding. Pitocin, a synthetic hormone used to make the uterus contract during and after labour, is structurally modelled on oxytocin.[51]

Weight loss

As the fat accumulated during pregnancy is used to produce milk, extended breastfeeding—at least 6 months—can help mothers lose weight.[52] However, weight loss is highly variable among lactating women; monitoring the diet and increasing the amount/intensity of exercise are more reliable ways of losing weight.[53] The 2007 review for the AHRQ found "The effect of breastfeeding in mothers on return-to-pre-pregnancy weight was negligible, and the effect of breastfeeding on postpartum weight loss was unclear."[14]

Natural postpartum infertility

Breastfeeding may delay the return to fertility for some women by suppressing ovulation. A breastfeeding woman may not ovulate, or have regular periods, during the entire lactation period. The period in which ovulation is absent differs for each woman. This Lactational amenorrhea has been used as an imperfect form of natural contraception, with a greater than 98% effectiveness during the first six months after birth if specific nursing behaviors are followed.[54] It is possible for some women to ovulate within two months after birth while fully breastfeeding.

Long-term health effects

For breastfeeding women, long-term health benefits include:

- Less risk of breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and endometrial cancer.[10][14][55][56]

- A 2009 study indicated that lactation for at least 24 months is associated with a 23% lower risk of coronary heart disease.[57]

- Although the 2007 review for the AHRQ found "no relationship between a history of lactation and the risk of osteoporosis"[14], mothers who breastfeed longer than eight months benefit from bone re-mineralisation.[58]

- Breastfeeding diabetic mothers require less insulin.[59]

- Reduced risk of post-partum bleeding.[51]

- According to a Malmö University study published in 2009, women who breast fed for a longer duration have a lower risk for contracting rheumatoid arthritis than women who breast fed for a shorter duration or who had never breast fed.[60]

Organisational endorsements

World Health Organization

| “ | The vast majority of mothers can and should breastfeed, just as the vast majority of infants can and should be breastfed. Only under exceptional circumstances can a mother’s milk be considered unsuitable for her infant. For those few health situations where infants cannot, or should not, be breastfed, the choice of the best alternative – expressed breast milk from an infant’s own mother, breast milk from a healthy wet-nurse or a human-milk bank, or a breast-milk substitute fed with a cup, which is a safer method than a feeding bottle and teat – depends on individual circumstances.[9] | ” |

The WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, after which "infants should receive nutritionally adequate and safe complementary foods while breastfeeding continues for up to two years of age or beyond."[9]

American Academy of Pediatrics

| “ | Extensive research using improved epidemiologic methods and modern laboratory techniques documents diverse and compelling advantages for infants, mothers, families, and society from breastfeeding and use of human milk for infant feeding. These advantages include health, nutritional, immunologic, developmental, psychologic, social, economic, and environmental benefits.[10] | ” |

The AAP recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life.[10] Furthermore, "breastfeeding should be continued for at least the first year of life and beyond for as long as mutually desired by mother and child."[10]

Breastfeeding difficulties

While breastfeeding is a natural human activity, difficulties are not uncommon. Putting the baby to the breast as soon as possible after the birth helps to avoid many problems. The AAP breastfeeding policy says: "Delay weighing, measuring, bathing, needle-sticks, and eye prophylaxis until after the first feeding is completed."[10] Many breastfeeding difficulties can be resolved with proper hospital procedures, properly trained midwives, doctors and hospital staff, and lactation consultants.[61] There are some situations in which breastfeeding may be harmful to the infant, including infection with HIV and acute poisoning by environmental contaminants such as lead.[42] The Institute of Medicine has reported that breast surgery, including breast implants or breast reduction surgery, reduces the chances that a woman will have sufficient milk to breast feed.[62] Rarely, a mother may not be able to produce breastmilk because of a prolactin deficiency. This may be caused by Sheehan's syndrome, an uncommon result of a sudden drop in blood pressure during childbirth typically due to hemorrhaging. In developed countries, many working mothers do not breast feed their children due to work pressures. For example, a mother may need to schedule for frequent pumping breaks, and find a clean, private and quiet place at work for pumping. These inconveniences may cause mothers to give up on breast feeding and use infant formula instead.

HIV infection

As breastfeeding can transmit HIV from mother to child, UNAIDS recommends avoidance of all breastfeeding where formula feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable and safe.[63] The qualifications are important. Some constituents of breast milk may protect from infection. High levels of certain polyunsaturated fatty acids in breast milk (including eicosadienoic, arachidonic and gamma-linolenic acids) are associated with a reduced risk of child infection when nursed by HIV-positive mothers. Arachidonic acid and gamma-linolenic acid may also reduce viral shedding of the HIV virus in breast milk.[64] Due to this, in underdeveloped nations infant mortality rates are lower when HIV-positive mothers breastfeed their newborns than when they use infant formula. However, differences in infant mortality rates have not been reported in better resourced areas.[65] Treating infants prophylactically with lamivudine (3TC) can help to decrease the transmission of HIV from mother to child by breastfeeding.[66] If free or subsidized formula is given to HIV-infected mothers, recommendations have been made to minimize the drawbacks such as possible disclosure of the mother's HIV status.[67]

Infant weight gain

Breastfed infants generally gain weight according to the following guidelines:

- 0–4 months: 6 oz. per week†

- 4–6 months: 4-5 oz. per week

- 6–12 months: 2-4 oz. per week

- † It is acceptable for some babies to gain 4–5 ounces per week. This average is taken from the lowest weight, not the birth weight.

The average breastfed baby doubles its birth weight in 5–6 months. By one year, a typical breastfed baby will weigh about 2½ times its birth weight. At one year, breastfed babies tend to be leaner than bottle fed babies.[68] By two years, differences in weight gain and growth between breastfed and formula-fed babies are no longer evident.[69]

Methods and considerations

There are many books and videos to advise mothers about breastfeeding. Lactation consultants in hospitals or private practice, and volunteer organisations of breastfeeding mothers such as La Leche League International also provide advice and support.

Early breastfeeding

In the half hour after birth, the baby's suckling reflex is strongest, and the baby is more alert, so it is the ideal time to start breastfeeding.[70] Early breast-feeding is associated with fewer nighttime feeding problems.[71]

Time and place for breastfeeding

Breastfeeding at least every two to three hours helps to maintain milk production. For most women, eight breastfeeding or pumping sessions every 24 hours keeps their milk production high.[10] Newborn babies may feed more often than this: 10 to 12 breastfeeding sessions every 24 hours is common, and some may even feed 18 times a day.[72] Feeding a baby "on demand" (sometimes referred to as "on cue"), means feeding when the baby shows signs of hunger; feeding this way rather than by the clock helps to maintain milk production and ensure the baby's needs for milk and comfort are being met. However, it may be important to recognize whether a baby is truly hungry, as breastfeeding too frequently may mean the child receives a disproportionately high amount of foremilk, and not enough hindmilk.[73]

"Experienced breastfeeding mothers learn that the sucking patterns and needs of babies vary. While some infants' sucking needs are met primarily during feedings, other babies may need additional sucking at the breast soon after a feeding even though they are not really hungry. Babies may also nurse when they are lonely, frightened or in pain."[74]

"Comforting and meeting sucking needs at the breast is nature's original design. Pacifiers (dummies, soothers) are a substitute for the mother when she can't be available. Other reasons to pacify a baby primarily at the breast include superior oral-facial development, prolonged lactational amenorrhea, avoidance of nipple confusion and stimulation of an adequate milk supply to ensure higher rates of breastfeeding success."[74]

Most US states now have laws that allow a mother to breastfeed her baby anywhere she is allowed to be. In hospitals, rooming-in care permits the baby to stay with the mother and improves the ease of breastfeeding. Some commercial establishments provide breastfeeding rooms, although laws generally specify that mothers may breastfeed anywhere, without requiring them to go to a special area. Dedicated breastfeeding rooms are generally preferred by women who are expressing milk while away from their baby.

Latching on, feeding and positioning

Correct positioning and technique for latching on can prevent nipple soreness and allow the baby to obtain enough milk.[75] The "rooting reflex" is the baby's natural tendency to turn towards the breast with the mouth open wide; mothers sometimes make use of this by gently stroking the baby's cheek or lips with their nipple in order to induce the baby to move into position for a breastfeeding session, then quickly moving baby onto the breast while baby's mouth is wide open.[76] In order to prevent nipple soreness and allow the baby to get enough milk, a large part of the breast and areola need to enter the baby's mouth.[75][77] To help the baby latch on well, tickle the baby's top lip with the nipple, wait until the baby's mouth opens wide, then bring the baby up towards the nipple quickly, so that the baby has a mouthful of nipple and areola. The nipple should be at the back of the baby's throat, with the baby's tongue lying flat in its mouth. Inverted or flat nipples can be massaged so that the baby will have more to latch onto. Resist the temptation to move towards the baby, as this can lead to poor attachment.

Pain in the nipple or breast is linked to incorrect breastfeeding techniques. Failure to latch on is one of the main reasons for ineffective feeding and can lead to infant health concerns. A 2006 study found that inadequate parental education, incorrect breastfeeding techniques, or both were associated with higher rates of preventable hospital admissions in newborns.[78]

The baby may pull away from the nipple after a few minutes or after a much longer period of time. Normal feeds at the breast can last a few sucks (newborns), from 10 to 20 minutes or even longer (on demand). Sometimes, after the finishing of a breast, the mother may offer the other breast.

While most women breastfeed their child in the cradling position, there are many ways to hold the feeding baby. It depends on the mother and child's comfort and the feeding preference of the baby. Some babies prefer one breast to the other, but the mother should offer both breasts at every nursing with her newborn.

When tandem breastfeeding, the mother is unable to move the baby from one breast to another and comfort can be more of an issue. As tandem breastfeeding brings extra strain to the arms, especially as the babies grow, many mothers of twins recommend the use of more supporting pillows.

Exclusive breastfeeding

Exclusive breastfeeding is defined as "an infant's consumption of human milk with no supplementation of any type (no water, no juice, no nonhuman milk, and no foods) except for vitamins, minerals, and medications."[10] National and international guidelines recommend that all infants be breastfed exclusively for the first six months of life. Breastfeeding may continue with the addition of appropriate foods, for two years or more. Exclusive breastfeeding has dramatically reduced infant deaths in developing countries by reducing diarrhea and infectious diseases. It has also been shown to reduce HIV transmission from mother to child, compared to mixed feeding.[80][81][82][83]

Exclusively breastfed infants feed anywhere from 6 to 14 times a day. Newborns consume from 30 to 90 ml (1 to 3 US fluid ounces) per feed. After the age of four weeks, babies consume about 120ml (4 US fluid ounces) per feed. Each baby is different, but as it grows the amount will increase. It is important to recognize the baby's hunger signs. It is assumed that the baby knows how much milk it needs and it is therefore advised that the baby should dictate the number, frequency, and length of each feed. The supply of milk from the breast is determined by the number and length of these feeds or the amount of milk expressed. The birth weight of the baby may affect its feeding habits, and mothers may be influenced by what they perceive its requirements to be. For example, a baby born small for gestational age may lead a mother to believe that her child needs to feed more than if it larger; they should, however, go by the demands of the baby rather than what they feel is necessary.

While it can be hard to measure how much food a breastfed baby consumes, babies normally feed to meet their own requirements.[84] Babies that fail to eat enough may exhibit symptoms of failure to thrive. If necessary, it is possible to estimate feeding from wet and soiled nappies (diapers): 8 wet cloth or 5–6 wet disposable, and 2–5 soiled per 24 hours suggests an acceptable amount of input for newborns older than 5–6 days old. After 2–3 months, stool frequency is a less accurate measure of adequate input as some normal infants may go up to 10 days between stools. Babies can also be weighed before and after feeds.

Expressing breast milk

When direct breastfeeding is not possible, a mother can express (artificially remove and store) her milk. With manual massage or using a breast pump, a woman can express her milk and keep it in freezer storage bags, a supplemental nursing system, or a bottle ready for use. Breast milk may be kept at room temperature for up to six hours , refrigerated for up to eight days or frozen for up to four to six months. Research suggests that the antioxidant activity in expressed breast milk decreases over time but it still remains at higher levels than in infant formula.[85]

Expressing breast milk can maintain a mother's milk supply when she and her child are apart. If a sick baby is unable to feed, expressed milk can be fed through a nasogastric tube.

Expressed milk can also be used when a mother is having trouble breastfeeding, such as when a newborn causes grazing and bruising. If an older baby bites the nipple, the mother's reaction - a jump and a cry of pain - is usually enough to discourage the child from biting again.

"Exclusively expressing", "exclusively pumping" and "EPing" are terms for a mother who feeds her baby exclusively on her breastmilk while not physically breastfeeding. This may arise because her baby is unable or unwilling to latch on to the breast. With good pumping habits, particularly in the first 12 weeks when the milk supply is being established, it is possible to produce enough milk to feed the baby for as long as the mother wishes. Kellymom has a page of links relating to exclusive pumping.[86]

It is generally advised to delay using a bottle to feed expressed breast milk until the baby is 4–6 weeks old and is good at sucking directly from the breast.[87] As sucking from a bottle takes less effort, babies can lose their desire to suck from the breast. This is called nursing strike or nipple confusion. To avoid this when feeding expressed breast milk (EBM) before 4–6 weeks of age, it is recommended that breast milk be given by other means such as feeding spoons or feeding cups. Also, EBM should be given by someone other than the breastfeeding mother (or wet nurse), so that the baby can learn to associate direct feeding with the mother (or wet nurse) and associate bottle feeding with other people.

Some women donate their expressed breast milk (EBM) to others, either directly or through a milk bank. Though historically the use of wet nurses was common, some women dislike the idea of feeding their own child with another woman's milk; others appreciate being able to give their baby the benefits of breast milk. Feeding expressed breast milk—either from donors or the baby's own mother—is the feeding method of choice for premature babies.[88] The transmission of some viral diseases through breastfeeding can be prevented by expressing breast milk and subjecting it to Holder pasteurisation.[89]

Mixed feeding

Predominant or mixed breastfeeding means feeding breast milk along with infant formula, baby food and even water, depending on the age of the child. Babies feed differently with artificial teats than from a breast. With the breast, the infant's tongue massages the milk out rather than sucking, and the nipple does not go as far into the mouth; with an artificial teat, an infant will suck harder and the milk may come in more rapidly. Therefore, mixing breastfeeding and bottle-feeding (or using a pacifier) before the baby is used to feeding from its mother can result in the infant preferring the bottle to the breast. Orthodontic teats, which are generally slightly longer, are closer to the nipple. Some mothers supplement feed with a small syringe or flexible cup to reduce the risk of artificial nipple preference.

Tandem breastfeeding

Feeding two children at the same time is called tandem breastfeeding The most common reason for tandem breastfeeding is the birth of twins, although women with closely spaced children can and do continue to nurse the older as well as the younger. As the appetite and feeding habits of each baby may not be the same, this could mean feeding each according to their own individual needs, and can also include breastfeeding them together, one on each breast.

In cases of triplets or more, it is a challenge for a mother to organize feeding around the appetites of all the babies. While breasts can respond to the demand and produce large quantities of milk, it is common for women to use alternatives. However, some mothers have been able to breastfeed triplets successfully.[90][91][92]

Tandem breastfeeding may also occur when a woman has a baby while breastfeeding an older child. During the late stages of pregnancy the milk will change to colostrum, and some older nurslings will continue to feed even with this change, while others may wean due to the change in taste or drop in supply. Feeding a child while being pregnant with another can also be considered a form of tandem feeding for the nursing mother, as she also provides the nutrition for two.[93]

Extended breastfeeding

Breastfeeding past two years is called "full term breastfeeding" or extended breastfeeding or "sustained breastfeeding" by supporters and those outside the U.S.[94] Supporters of extended breastfeeding believe that all the benefits of human milk, nutritional, immunological and emotional, continue for as long as a child nurses. Often the older child will nurse infrequently or sporadically as a way of bonding with the mother.

It used to be common worldwide, and still is in developing nations such as those in Africa, for more than one woman to breastfeed a child. Shared breastfeeding is a risk factor for HIV infection in infants.[95] A woman who is engaged to breastfeed another's baby is known as a wet nurse. Islam has codified the relationship between this woman and the infants she nurses, and also between the infants when they grow up, so that milk siblings are considered as blood siblings and cannot marry (mahram). Shared breastfeeding can incur strong negative reactions in the Anglosphere;[96] American feminist activist Jennifer Baumgardner has written about her experiences in New York with this issue.[97]

Weaning

Weaning is the process of introducing the infant to other food and reducing the supply of breast milk. The infant is fully weaned when it no longer receives any breast milk. Most mammals stop producing the enzyme lactase at the end of weaning, and become lactose intolerant. Humans often have a mutation, with frequency depending primarily on ethnic background, that allows the production of lactase throughout life and so can drink milk - usually cow or goat milk - well beyond infancy.[98] In humans, the psychological factors involved in the weaning process are crucial for both mother and infant as issues of closeness and separation are very prominent during this stage.[99]

In the past bromocriptine was in some countries frequently used to reduce the engorgement experienced by many women during weaning. This is now done only in exceptional cases as it causes frequent side effects, offers very little advantage over non-medical management and the possibility of serious side effects can not be ruled out.[100] Other medications such as cabergoline, lisuride or birth control pills may be occasionally used as lactation suppressants.

History of breastfeeding

For hundreds of thousands of years, humans, like all other mammals, fed their young milk. Before the twentieth century, alternatives to breastfeeding were rare. Attempts in 15th century Europe to use cow or goat milk were not very positive. In the 18th century, flour or cereal mixed with broth were introduced as substitutes for breastfeeding, but this did not have a favorable outcome, either. True commercial infant formulas appeared on the market in the mid 19th Century but their use did not become widespread until after WWII. As the superior qualities of breast milk became better-established in medical literature, breastfeeding rates have increased and countries have enacted measures to protect the rights of infants and mothers to breastfeed.

Sociological factors with breastfeeding

Researchers have found several social factors that correlate with differences in initiation, frequency, and duration of breastfeeding practices of mothers. Race, ethnic differences and socioeconomic status and other factors have been shown to affect a mother’s choice whether or not to breastfeed and how long she breastfeeds her child.

- Race and culture Singh et al. also found that African American women are less likely than white women of similar socioeconomic status to breastfeed and Hispanic women are more likely to breastfeed. The Center of Disease Control used information from the National Immunization Survey to determine the proportion of Caucasian and African American children that were ever breast fed. They found that 71.5% of Caucasians had breastfed their child while only 50.1% of African Americans had. At six months of age this fell to 53.9% of Caucasian mothers and 43.2% of African American mothers who were still breastfeeding.

- Income Deborah L. Dee's research found that women and children who qualify for WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children were among those who were least likely to initiate breastfeeding. Income level can also contribute to women discontinuing breastfeeding early. More highly educated women are more likely to have access to information regarding difficulties with breastfeeding, allowing them to continue breastfeeding through difficulty rather than weaning early. Women in higher status jobs are more likely to have access to a lactation room and suffer less social stigma from having to breastfeed or express breastmilk at work. In addition, women who are unable to take an extended leave from work following the birth of their child are less likely to continue breastfeeding when they return to work.

- Other factors Other factors they found to have an effect on breastfeeding are “household composition, metropolitan/non-metropolitan residence, parental education, household income or poverty status, neighborhood safety, familial support, maternal physical activity, and household smoking status.”

Breastfeeding in public

Role of marketing

Controversy has arisen over the marketing of breast milk vs. formula; particularly how it affects the education of mothers in third world counties and their comprehension (or lack thereof) of the health benefits of breastfeeding.[101] The most famous example being the Nestlé boycott, which arose in the 1970s and continues to be supported by high-profile stars and international groups to this day.[102][103]

In 1981, the World Health Assembly (WHA) adopted Resolution WHA34.22 which includes the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes.

See also

- Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative

- Baby-led weaning

- Breast shell

- Dairy allergy

- Erotic lactation

- Human milk banking in North America

- Lactation

- Lactation room

- Male lactation

- Milk line

- Nursing chair

References

- ↑ Picciano M (2001). "Nutrient composition of human milk". Pediatr Clin North Am 48 (1): 53–67. doi:10.1016/S0031-3955(05)70285-6. PMID 11236733.

- ↑ Riordan JM (1997). "The cost of not breastfeeding: a commentary". J Hum Lact 13 (2): 93–97. doi:10.1177/089033449701300202. PMID 9233193.

- ↑ Bartick M, Reinhold A (2010-04-05). "The burden of suboptimal breastfeeding in the United States: a pediatric cost analysis". Pediatrics 125 (5): e1048–56. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-1616. PMID 20368314. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/abstract/peds.2009-1616v1. "If 90% of US families could comply with medical recommendations to breastfeed exclusively for 6 months, the United States would save $13 billion per year and prevent an excess 911 deaths".

- ↑ Falco M (2010-04-05). "Study: lack of breastfeeding costs lives, billions of dollars". CNN. http://www.cnn.com/2010/HEALTH/04/05/breastfeeding.costs.

- ↑ Horton S, Sanghvi T, Phillips M, et al. (1996). "Breastfeeding promotion and priority setting in health". Health Policy Plan 11 (2): 156–68. doi:10.1093/heapol/11.2.156. PMID 10158457.

- ↑ Kramer M, Kakuma R (2002). "Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (1): CD003517. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003517. PMID 11869667.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Baker R (2003). "Human milk substitutes. An American perspective". Minerva Pediatr 55 (3): 195–207. PMID 12900706.

- ↑ Agostoni C, Haschke F (2003). "Infant formulas. Recent developments and new issues". Minerva Pediatr 55 (3): 181–94. PMID 12900705.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 World Health Organization. (2003). Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization and UNICEF. ISBN 9241562218. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2003/9241562218.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 Gartner LM, et al. (2005). "Breastfeeding and the use of human milk [policy statement"]. Pediatrics 115 (2): 496–506. doi:10.1542/peds.2004-2491. PMID 15687461. http://aappolicy.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/pediatrics;115/2/496.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Benefits of Breastfeeding". U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.4woman.gov/breastfeeding/index.cfm?page=227. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommwen LA. Maternal weight-loss patterns during the menstrual cycle. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;58: 162-166

- ↑ Fisher D (2006 November). "Social drugs and breastfeeding". Queensland, Australia: Health e-Learning. http://www.health-e-learning.com/content/view/32/63/.

- ↑ 14.00 14.01 14.02 14.03 14.04 14.05 14.06 14.07 14.08 14.09 14.10 Ip S, Chung M, Raman G, et al. (2007). "Breastfeeding and maternal and infant health outcomes in developed countries". Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep) (153): 1–186. PMID 17764214. http://www.ahrq.gov/downloads/pub/evidence/pdf/brfout/brfout.pdf. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 Horta BL, Bahl R, Martines JC, Victora CG (2007). Evidence on the long-term effects of breastfeeding: systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. ISBN 9789241595230. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2007/9789241595230_eng.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Breastfeeding". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/. Retrieved 2007-01-23.

- ↑ Kunz C, Rodriguez-Palmero M, Koletzko B, Jensen R (1999). "Nutritional and biochemical properties of human milk, Part I: General aspects, proteins, and carbohydrates". Clin Perinatol 26 (2): 307–33. PMID 10394490.

- ↑ Rodriguez-Palmero M, Koletzko B, Kunz C, Jensen R (1999). "Nutritional and biochemical properties of human milk: II. Lipids, micronutrients, and bioactive factors". Clin Perinatol 26 (2): 335–59. PMID 10394491.

- ↑ Glass RI, Svennerholm AM, Stoll BJ, et al. (1983). "Protection against cholera in breast-fed children by antibodies in breast milk". N. Engl. J. Med. 308 (23): 1389–92. PMID 6843632.

- ↑ Owen MJ, Baldwin CD, Swank PR, Pannu AK, Johnson DL, Howie VM (1993). "Relation of infant feeding practices, cigarette smoke exposure, and group child care to the onset and duration of otitis media with effusion in the first two years of life". J. Pediatr. 123 (5): 702–11. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(05)80843-1. PMID 8229477.

- ↑ Dewey KG, Heinig MJ, Nommsen-Rivers LA (1995). "Differences in morbidity between breast-fed and formula-fed infants". J. Pediatr. 126 (5 Pt 1): 696–702. doi:10.1016/S0022-3476(95)70395-0. PMID 7751991.

- ↑ Blaymore Bier JA, Oliver T, Ferguson A, Vohr BR (2002). "Human milk reduces outpatient upper respiratory symptoms in premature infants during their first year of life". J Perinatol 22 (5): 354–9. doi:10.1038/sj.jp.7210742. PMID 12082468.

- ↑ Mårild S, Hansson S, Jodal U, Odén A, Svedberg K (2004). "Protective effect of breastfeeding against urinary tract infection". Acta Paediatr. 93 (2): 164–8. doi:10.1080/08035250310007402. PMID 15046267.

- ↑ Horne RS, Parslow PM, Ferens D, Watts AM, Adamson TM (2004). "Comparison of evoked arousability in breast and formula fed infants". Arch. Dis. Child. 89 (1): 22–5. PMID 14709496.

- ↑ Vennemann MM, Bajanowski T, Brinkmann B, Jorch G, Yücesan K, Sauerland C, Mitchell EA; GeSID Study Group (2009). "Does breastfeeding reduce the risk of sudden infant death syndrome?". Pediatrics 123 (3): e406–10. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-2145. PMID 19254976. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/content/full/123/3/e406.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Horwood LJ, Darlow BA, Mogridge N (2001). "Breast milk feeding and cognitive ability at 7-8 years". Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 84 (1): F23–7. doi:10.1136/fn.84.1.F23. PMID 11124919.

- ↑ Evenhouse E, Reilly S (2005). "Improved estimates of the benefits of breastfeeding using sibling comparisons to reduce selection bias". Health Serv Res 40 (6 Pt 1): 1781–802. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00453.x. PMID 16336548. PMC 1361236. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=1361236.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Der G, Batty GD, Deary IJ (2006). "Effect of breast feeding on intelligence in children: prospective study, sibling pairs analysis, and meta-analysis". BMJ 333 (7575): 945. doi:10.1136/bmj.38978.699583.55. PMID 17020911.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Caspi A, Williams B, Kim-Cohen J, et al. (2007). "Moderation of breastfeeding effects on the IQ by genetic variation in fatty acid metabolism". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104 (47): 18860–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.0704292104. PMID 17984066.

- ↑ Paddock C (6 November 2007). "IQ boost from breastfeeding linked to common gene". Medical News Today. http://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/87775.php. Retrieved 20 September 2009.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Kramer MS, Aboud F, Mironova E, et al. (2008). "Breastfeeding and child cognitive development: new evidence from a large randomized trial". Arch Gen Psychiatry 65 (5): 578–84. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.578. PMID 18458209. http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/full/65/5/578.

- ↑ Perez-Bravo F, Carrasco E, Gutierrez-Lopez MD, Martinez MT, Lopez G, de los Rios MG (1996). "Genetic predisposition and environmental factors leading to the development of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in Chilean children". J. Mol. Med. 74 (2): 105–9. doi:10.1007/BF00196786. PMID 8820406.

- ↑ Owen CG, Martin RM, Whincup PH, Smith GD, Cook DG (2006). "Does breastfeeding influence risk of type 2 diabetes in later life? A quantitative analysis of published evidence". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 84 (5): 1043–54. PMID 17093156.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Mayer-Davis EJ, Dabelea D, Lamichhane AP, et al. (2008). "Breast-feeding and type 2 diabetes in the youth of three ethnic groups: the SEARCh for diabetes in youth case-control study". Diabetes Care 31 (3): 470–5. doi:10.2337/dc07-1321. PMID 18071004.

- ↑ Armstrong J, Reilly JJ (2002). "Breastfeeding and lowering the risk of childhood obesity". Lancet 359 (9322): 2003–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08837-2. PMID 12076560.

- ↑ Arenz S, Rückerl R, Koletzko B, von Kries R (2004). "Breast-feeding and childhood obesity--a systematic review". Int. J. Obes. Relat. Metab. Disord. 28 (10): 1247–56. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0802758. PMID 15314625.

- ↑ Greer FR, Sicherer SH, Burks AW (2008). "Effects of early nutritional interventions on the development of atopic disease in infants and children: the role of maternal dietary restriction, breastfeeding, timing of introduction of complementary foods, and hydrolyzed formulas". Pediatrics (journal) 121 (1): 183–91. doi:10.1542/peds.2007-3022. PMID 18166574.

- ↑ Oddy WH, Holt PG, Sly PD, et al. (1999). "Association between breast feeding and asthma in 6 year old children: findings of a prospective birth cohort study". BMJ 319 (7213): 815–9. PMID 10496824.

- ↑ Pratt HF (1984). "Breastfeeding and eczema". Early Hum. Dev. 9 (3): 283–90. doi:10.1016/0378-3782(84)90039-2. PMID 6734490.

- ↑ Lucas A, Cole TJ (1990). "Breast milk and neonatal necrotising enterocolitis". Lancet 336 (8730): 1519–23. doi:10.1016/0140-6736(90)93304-8. PMID 1979363.

- ↑ Kramer MS, Matush L, Vanilovich I, et al. (2007). "Effect of prolonged and exclusive breast feeding on risk of allergy and asthma: cluster randomised trial". BMJ 335 (7624): 815. doi:10.1136/bmj.39304.464016.AE. PMID 17855282.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Mead MN (2008). "Contaminants in human milk: weighing the risks against the benefits of breastfeeding". Environ Health Perspect 116 (10): A426–34. doi:10.1289/ehp.116-a426. PMID 18941560. PMC 2569122. http://www.ehponline.org/members/2008/116-10/focus.html.

- ↑ Akobeng AK, Ramanan AV, Buchan I, Heller RF (2006). "Effect of breast feeding on risk of coeliac disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies". Arch. Dis. Child. 91 (1): 39–43. doi:10.1136/adc.2005.082016. PMID 16287899.

- ↑ Nichols HB, Trentham-Dietz A, Sprague BL, et al (May 2008). "Effects of birth order and maternal age on breast cancer risk: modification by whether women had been breast-fed". Epidemiology 19 (3): 417–23. doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816a1cff. PMID 18379425.

- ↑ Williams MJ, Williams SM, Poulton R (Feb 2006). "Breast feeding is related to C reactive protein concentration in adult women". J Epidemiol Community Health 60 (2): 146–8. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.039222. PMID 16415265. PMC 2566145. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=16415265. Retrieved 2009-09-19.

- ↑ Leeson C, Kattenhorn M, Deanfield J, Lucas A (2001). "Duration of breast feeding and arterial distensibility in early adult life: population based study". BMJ 322 (7287): 643–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.322.7287.643. PMID 11250848. PMC 26543. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/reprint/322/7287/643.

- ↑ Feldman S (July-August 2000). "Nursing Through Pregnancy". New Beginnings (La Leche League International) 17 (4): 116–118, 145. http://www.lalecheleague.org/NB/NBJulAug00p116.html. Retrieved 2007-03-15.

- ↑ Pisacane A, Continisio GI, Aldinucci M, D'Amora S, Continisio P (2005). "A controlled trial of the father's role in breastfeeding promotion". Pediatrics 116 (4): e494–8. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-0479. PMID 16199676. http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16199676.

- ↑ van Willigen J (2002). Applied anthropology: an introduction. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 0897898338.

- ↑ Stuart-Macadam P, Dettwyler K (1995). Breastfeeding: biocultural perspectives. Aldine de Gruyter. pp. 131. ISBN 978-0-202-01192-9.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Chua S, Arulkumaran S, Lim I, Selamat N, Ratnam S (1994). "Influence of breastfeeding and nipple stimulation on postpartum uterine activity". Br J Obstet Gynaecol 101 (9): 804–5. PMID 7947531.

- ↑ Dewey K, Heinig M, Nommsen L (1993). "Maternal weight-loss patterns during prolonged lactation". Am J Clin Nutr 58 (2): 162–6. PMID 8338042.

- ↑ Lovelady C, Garner K, Moreno K, Williams J (2000). "The effect of weight loss in overweight, lactating women on the growth of their infants". N Engl J Med 342 (7): 449–53. doi:10.1056/NEJM200002173420701. PMID 10675424.

- ↑ Price C; Robinson S (2004). Birth: Conceiving, Nurturing and Giving Birth to Your Baby. McMillan. pp. 489. ISBN 1-4050-3612-5.

- ↑ Rosenblatt K, Thomas D (1995). "Prolonged lactation and endometrial cancer. WHO Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives". Int J Epidemiol 24 (3): 499–503. PMID 7672888.

- ↑ Newcomb P, Trentham-Dietz A (2000). "Breast feeding practices in relation to endometrial cancer risk, USA". Cancer Causes Control 11 (7): 663–7. doi:10.1023/A:1008978624266. PMID 10977111.

- ↑ Stuebe AM, Michels KB, Willett WC, Manson JE, Rexrode K, Rich-Edwards JW (2009). "Duration of lactation and incidence of myocardial infarction in middle to late adulthood". Am J Obstet Gynecol 200 (2): 138.e1–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2008.10.001. PMID 19110223. PMC 2684022. http://www.ajog.org/article/PIIS000293780802005X/fulltext.

- ↑ Melton III L; Bryant S, Wahner H, O'Fallon W, Malkasian G, Judd H, Riggs B (March 1993). "Influence of breastfeeding and other reproductive factors on bone mass later in life". Osteoporosis International (London: Springer) 3 (2): 76. doi:10.1007/BF01623377. PMID 8453194.

- ↑ Rayburn W, Piehl E, Lewis E, Schork A, Sereika S, Zabrensky K (1985). "Changes in insulin therapy during pregnancy". Am J Perinatol 2 (4): 271–5. doi:10.1055/s-2007-999968. PMID 3902039.

- ↑ Pikwer M, Bergström U, Nilsson JA, et al (Apr 2009). "Breast feeding, but not use of oral contraceptives, is associated with a reduced risk of rheumatoid arthritis". Ann Rheum Dis 68 (4): 526–30. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.084707. PMID 18477739.

- ↑ Newman J; Pitman T (2000). Dr. Jack Newman's guide to breastfeeding. HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0006385680.

- ↑ "Breast Surgery Likely to Cause Breastfeeding Problems". The Implant Information Project of the Nat. Research Center for Women & Families. February 2008. http://www.breastimplantinfo.org/augment/brstfdg122000.html.

- ↑ "Nutrition and food security". http://www.unaids.org/en/PolicyAndPractice/CareAndSupport/NutrAndFoodSupport. Retrieved 2008-11-19.

- ↑ Villamor E, Koulinska IN, Furtado J, et al. (2007). "Long-chain n-6 polyunsaturated fatty acids in breast milk decrease the risk of HIV transmission through breastfeeding". Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 86 (3): 682–9. PMID 17823433.

- ↑ Hilderbrand K., Goemaere E., Coetzee E. (2003). "The prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programme and infant feeding practices". South African Medical Journal 93 (10): 779–781. PMID 14652971.

- ↑ Kilewo C, Karlsson K, Massawe A, et al. (2008). "Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 through breast-feeding by treating infants prophylactically with lamivudine in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania: the Mitra Study". J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 48 (3): 315–323. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e31816e395c. PMID 18344879.

- ↑ Coutsoudis A, Goga AE, Rollins N, Coovadia HM (2002). "Free formula milk for infants of HIV-infected women: blessing or curse?". Health Policy and Planning 17 (2): 154–160. doi:10.1093/heapol/17.2.154. PMID 12000775. http://heapol.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/reprint/17/2/154.

- ↑ "Weight gain (Growth patterns)". AskDrSears.com. http://www.askdrsears.com/html/2/T023600.asp. Retrieved 2007-04-03.

- ↑ Mohrbacher N, Stock J (2003). The breastfeeding answer book (3rd (revised) ed.). Schaumburg, Ill.: La Leche League International. ISBN 0-912500-92-1.

- ↑ Widstrom AM, Wahlberg V, Matthiesen AS, Eneroth P, Uvnas-Moberg K, Werner S, et al. Short-term effects of early suckling and touch of the nipple on maternal behavior. Early Hum Dev 1990; 21:153-63.

- ↑ Renfrew MJ, Lang S. Early versus delayed initiation of breastfeeding. In: The Cochrane Library [on CD-ROM]. Oxford: Update Software;1998.

- ↑ "Infant feeding – Breast or bottle and how to breast feed". http://www.patient.co.uk/showdoc/40002328/. Retrieved 2007-05-26.

- ↑ V Livingstone. The Art of Successful Breastfeeding. [VHS]. Vancouver, BC, Canada: New Vision Media Ltd..

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Marasco L (1998 Apr-May). "Common breastfeeding myths". Leaven 34 (2): 21–24. http://www.llli.org/llleaderweb/LV/LVAprMay98p21.html. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 "Proper positioning and latch-on skills". AskDrSears.com. 2006. http://www.askdrsears.com/html/2/T021000.asp. Retrieved 2008-09-24.

- ↑ Natural Birth and Baby Care.com

- ↑ "Breastfeeding Guidelines". Rady Children's Hospital San Diego. http://www.chsd.org/1438.cfm. Retrieved 2007-03-04.

- ↑ Paul I, Lehman E, Hollenbeak C, Maisels M (2006). "Preventable newborn readmissions since passage of the Newborns' and Mothers' Health Protection Act". Pediatrics 118 (6): 2349–58. doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2043. PMID 17142518.

- ↑ http://www.drpaul.com/breastfeeding/colostrum.html

- ↑ Coutsoudis A, Pillay K, Kuhn L, Spooner E, Tsai WY, Coovadia HM: Method of feeding and transmission of HIV-1 from mothers to children by 15 months of age: prospective cohort study from Durban, South Africa. Aids 2001, 15(3):379-387

- ↑ Coovadia HM, Rollins NC, Bland RM, Little K, Coutsoudis A, Bennish ML, Newell ML: Mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 infection during exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life: an intervention cohort study. Lancet 2007, 369(9567):1107-1116.

- ↑ Coutsoudis A, Pillay K, Spooner E, Kuhn L, Coovadia HM: Influence of infant-feeding patterns on early mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Durban, South Africa: a prospective cohort study. South African Vitamin A Study Group. Lancet 1999, 354(9177):471-476.

- ↑ Iliff PJ, Piwoz EG, Tavengwa NV, Zunguza CD, Marinda ET, Nathoo KJ, Moulton LH, Ward BJ, Humphrey JH: Early exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of postnatal HIV-1 transmission and increases HIV-free survival. Aids 2005, 19(7):699-708.

- ↑ Iwinski S (2006). "Is Weighing Baby to Measure Milk Intake a Good Idea?". LEAVEN 42 (3): 51–3. http://www.lalecheleague.org/llleaderweb/LV/LVJulAugSep06p51.html. Retrieved 2007-04-08.

- ↑ Hanna N; Ahmed K, Anwar N, Petrova A, M Hiatt M, Hegyi T (November 2004). "Effect of storage on breast milk antioxidant activity". Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed (BMJ Publishing Group Ltd) 89 (6): F518–20. doi:10.1136/adc.2004.049247. PMID 15499145.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Arlene Eisenberg (1989). What to Expect the First Year. Workman Publishing Company. ISBN 0894805770.

- ↑ Spatz D (2006). "State of the science: use of human milk and breast-feeding for vulnerable infants". J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 20 (1): 51–5. PMID 16508463.

- ↑ Tully DB, Jones F, Tully MR (2001). "Donor milk: what's in it and what's not". J Hum Lact 17 (2): 152–5. doi:10.1177/089033440101700212. PMID 11847831. http://jhl.sagepub.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=11847831.

- ↑ Grunberg R (1992). "Breastfeeding multiples: Breastfeeding triplets". New Beginnings 9 (5): 135–6. http://www.lalecheleague.org/NB/NBSepOct92p135.html.

- ↑ Australian Breastfeeding Association: Breastfeeding triplets, quads and higher

- ↑ Association of Radical Midwives: Breastfeeding triplets

- ↑ Flower H (2003). Adventures in Tandem Nursing: Breastfeeding During Pregnancy and Beyond. La Leche League International. ISBN 978-0912500973.

- ↑ La Leche League International. "Report from the Board: Update from the LLLI Board of Directors". LLL. http://lalecheleague.org/llleaderweb/LV/LVAprMay03p26.html. Retrieved 2007-08-02.

- ↑ Alcorn K (2004-08-24). "Shared breastfeeding identified as new risk factor for HIV". Aidsmap. http://www.aidsmap.com/en/news/72E08565-12B7-43CF-A71E-7A57292B30DF.asp. Retrieved 2007-04-10.

- ↑ Guardian Unlimited: Not your mother's milk

- ↑ Jennifer Baumgardner, Breast Friends, Babble, 2007

- ↑ http://www.aafp.org/afp/20020501/1845.html AAFP.org

- ↑ The perils of intimacy: Closeness and distance in feeding and weaning. Daws, Dilys Source:Journal of Child Psychotherapy, Vol 23(2), Aug, 1997. pp. 179-199

- ↑ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (1994-08-17). "FDA moves to end use of bromocriptine for postpartum breast engorgement". Archived from the original on 2007-12-23. http://web.archive.org/web/20071223043815/http://www.fda.gov/bbs/topics/ANSWERS/ANS00594.html. Retrieved 2009-09-22.

- ↑ [2] Infant Feeding Action Coalition Canada

- ↑ Milking it Joanna Moorhead, The Guardian, May 15, 2007

- ↑ "Writers boycott literary festival". BBC News. 27 May 2002. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/2010324.stm. Retrieved 2007-06-07.

Further reading

- Baumslag N, Michels DL (1995). Milk, money, and madness: the culture and politics of breastfeeding. Westport, Conn.: Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 0-89789-407-3.

- Hausman B (2003). Mother's milk: breastfeeding controversies in American culture. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96656-6.

- Huggins K (1999). The nursing mother's companion (4th ed.). Boston, Mass.: Harvard Common Press. ISBN 1-55832-152-7.

- Pryor G (1997). Nursing mother, working mother: the essential guide for breastfeeding and staying close to your baby after you return to work. Boston, Mass.: Harvard Common Press. ISBN 1-55832-116-0.

- Torgus J, Gotsch G (2004). The womanly art of breastfeeding (7th ed.). Schaumburg, Ill.: La Leche League International. ISBN 0-912500-98-0.

External links

- Breastfeeding at the Open Directory Project

- Human Milk Secretion: An Overview US National Institute of Health

- Breastfeeding Resources La Leche League International

- Breast-Feeding Past Infancy ABC News

- Breast-Feeding Content Resources WHO reports on Breast Feeding

- Health risks of not breastfeeding US Department of Health & Human Services

- The World Alliance for Breastfeeding Action (WABA) is a global network of individuals & organisations concerned with the protection, promotion & support of breastfeeding worldwide.

- Breastfeeding: NHS Choices

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[[ta:தாய்ப்பாலூட்டல்