Social network

| Sociology |

|---|

|

| Portal |

| Theory and History |

|

Positivism · Antipositivism |

| Research methods |

|

Quantitative · Qualitative |

| Topics and Subfields |

|

cities · class · crime · culture Categories and lists

|

A social network is a social structure made up of individuals (or organizations) called "nodes," which are tied (connected) by one or more specific types of interdependency, such as friendship, kinship, common interest, financial exchange, dislike, sexual relationships, or relationships of beliefs, knowledge or prestige.

Social network analysis views social relationships in terms of network theory consisting of nodes and ties. Nodes are the individual actors within the networks, and ties are the relationships between the actors. The resulting graph-based structures are often very complex. There can be many kinds of ties between the nodes. Research in a number of academic fields has shown that social networks operate on many levels, from families up to the level of nations, and play a critical role in determining the way problems are solved, organizations are run, and the degree to which individuals succeed in achieving their goals.

In its simplest form, a social network is a map of all of the relevant ties between all the nodes being studied. The network can also be used to measure social capital -- the value that an individual gets from the social network. These concepts are often displayed in a social network diagram, where nodes are the points and ties are the lines.

Contents |

Social network analysis

Social network analysis (related to network theory) has emerged as a key technique in modern sociology. It has also gained a significant following in anthropology, biology, communication studies, economics, geography, information science, organizational studies, social psychology, and sociolinguistics, and has become a popular topic of speculation and study.

People have used the idea of "social network" loosely for over a century to connote complex sets of relationships between members of social systems at all scales, from interpersonal to international. In 1954, J. A. Barnes started using the term systematically to denote patterns of ties, encompassing concepts traditionally used by the public and those used by social scientists: bounded groups (e.g., tribes, families) and social categories (e.g., gender, ethnicity). Scholars such as S.D. Berkowitz, Stephen Borgatti, Ronald Burt, Kathleen Carley, Martin Everett, Katherine Faust, Linton Freeman, Mark Granovetter, David Knoke, David Krackhardt, Peter Marsden, Nicholas Mullins, Anatol Rapoport, Stanley Wasserman, Barry Wellman, Douglas R. White, and Harrison White expanded the use of systematic social network analysis.[1]

Social network analysis has now moved from being a suggestive metaphor to an analytic approach to a paradigm, with its own theoretical statements, methods, social network analysis software, and researchers. Analysts reason from whole to part; from structure to relation to individual; from behavior to attitude. They typically either study whole networks (also known as complete networks), all of the ties containing specified relations in a defined population, or personal networks (also known as egocentric networks), the ties that specified people have, such as their "personal communities".[2] The distinction between whole/complete networks and personal/egocentric networks has depended largely on how analysts were able to gather data. That is, for groups such as companies, schools, or membership societies, the analyst was expected to have complete information about who was in the network, all participants being both potential egos and alters. Personal/egocentric studies were typically conducted when identities of egos were known, but not their alters. These studies rely on the egos to provide information about the identities of alters and there is no expectation that the various egos or sets of alters will be tied to each other. A snowball network refers to the idea that the alters identified in an egocentric survey then become egos themselves and are able in turn to nominate additional alters. While there are severe logistic limits to conducting snowball network studies, a method for examining hybrid networks has recently been developed in which egos in complete networks can nominate alters otherwise not listed who are then available for all subsequent egos to see.[3] The hybrid network may be valuable for examining whole/complete networks that are expected to include important players beyond those who are formally identified. For example, employees of a company often work with non-company consultants who may be part of a network that cannot fully be defined prior to data collection.

Several analytic tendencies distinguish social network analysis:[4]

- There is no assumption that groups are the building blocks of society: the approach is open to studying less-bounded social systems, from nonlocal communities to links among websites.

- Rather than treating individuals (persons, organizations, states) as discrete units of analysis, it focuses on how the structure of ties affects individuals and their relationships.

- In contrast to analyses that assume that socialization into norms determines behavior, network analysis looks to see the extent to which the structure and composition of ties affect norms.

The shape of a social network helps determine a network's usefulness to its individuals. Smaller, tighter networks can be less useful to their members than networks with lots of loose connections (weak ties) to individuals outside the main network. More open networks, with many weak ties and social connections, are more likely to introduce new ideas and opportunities to their members than closed networks with many redundant ties. In other words, a group of friends who only do things with each other already share the same knowledge and opportunities. A group of individuals with connections to other social worlds is likely to have access to a wider range of information. It is better for individual success to have connections to a variety of networks rather than many connections within a single network. Similarly, individuals can exercise influence or act as brokers within their social networks by bridging two networks that are not directly linked (called filling structural holes).[5]

The power of social network analysis stems from its difference from traditional social scientific studies, which assume that it is the attributes of individual actors—whether they are friendly or unfriendly, smart or dumb, etc.—that matter. Social network analysis produces an alternate view, where the attributes of individuals are less important than their relationships and ties with other actors within the network. This approach has turned out to be useful for explaining many real-world phenomena, but leaves less room for individual agency, the ability for individuals to influence their success, because so much of it rests within the structure of their network.

Social networks have also been used to examine how organizations interact with each other, characterizing the many informal connections that link executives together, as well as associations and connections between individual employees at different organizations. For example, power within organizations often comes more from the degree to which an individual within a network is at the center of many relationships than actual job title. Social networks also play a key role in hiring, in business success, and in job performance. Networks provide ways for companies to gather information, deter competition, and collude in setting prices or policies.[6]

History of social network analysis

A summary of the progress of social networks and social network analysis has been written by Linton Freeman.[7]

Precursors of social networks in the late 1800s include Émile Durkheim and Ferdinand Tönnies. Tönnies argued that social groups can exist as personal and direct social ties that either link individuals who share values and belief (gemeinschaft) or impersonal, formal, and instrumental social links (gesellschaft). Durkheim gave a non-individualistic explanation of social facts arguing that social phenomena arise when interacting individuals constitute a reality that can no longer be accounted for in terms of the properties of individual actors. He distinguished between a traditional society – "mechanical solidarity" – which prevails if individual differences are minimized, and the modern society – "organic solidarity" – that develops out of cooperation between differentiated individuals with independent roles.

Georg Simmel, writing at the turn of the twentieth century, was the first scholar to think directly in social network terms. His essays pointed to the nature of network size on interaction and to the likelihood of interaction in ramified, loosely-knit networks rather than groups (Simmel, 1908/1971).

After a hiatus in the first decades of the twentieth century, three main traditions in social networks appeared. In the 1930s, J.L. Moreno pioneered the systematic recording and analysis of social interaction in small groups, especially classrooms and work groups (sociometry), while a Harvard group led by W. Lloyd Warner and Elton Mayo explored interpersonal relations at work. In 1940, A.R. Radcliffe-Brown's presidential address to British anthropologists urged the systematic study of networks.[8] However, it took about 15 years before this call was followed-up systematically.

Social network analysis developed with the kinship studies of Elizabeth Bott in England in the 1950s and the 1950s-1960s urbanization studies of the University of Manchester group of anthropologists (centered around Max Gluckman and later J. Clyde Mitchell) investigating community networks in southern Africa, India and the United Kingdom. Concomitantly, British anthropologist S.F. Nadel codified a theory of social structure that was influential in later network analysis.[9]

In the 1960s-1970s, a growing number of scholars worked to combine the different tracks and traditions. One group was centered around Harrison White and his students at the Harvard University Department of Social Relations: Ivan Chase, Bonnie Erickson, Harriet Friedmann, Mark Granovetter, Nancy Howell, Joel Levine, Nicholas Mullins, John Padgett, Michael Schwartz and Barry Wellman. Also important in this early group were Charles Tilly, who focused on networks in political sociology and social movements, and Stanley Milgram, who developed the "six degrees of separation" thesis.[10] Mark Granovetter and Barry Wellman are among the former students of White who have elaborated and popularized social network analysis.[11]

White's was not the only group. Significant independent work was done by scholars elsewhere: University of California Irvine social scientists interested in mathematical applications, centered around Linton Freeman, including John Boyd, Susan Freeman, Kathryn Faust, A. Kimball Romney and Douglas White; quantitative analysts at the University of Chicago, including Joseph Galaskiewicz, Wendy Griswold, Edward Laumann, Peter Marsden, Martina Morris, and John Padgett; and communication scholars at Michigan State University, including Nan Lin and Everett Rogers. A substantively-oriented University of Toronto sociology group developed in the 1970s, centered on former students of Harrison White: S.D. Berkowitz, Harriet Friedmann, Nancy Leslie Howard, Nancy Howell, Lorne Tepperman and Barry Wellman, and also including noted modeler and game theorist Anatol Rapoport.In terms of theory, it critiqued methodological individualism and group-based analyses, arguing that seeing the world as social networks offered more analytic leverage.[12]

Research

Social network analysis has been used in epidemiology to help understand how patterns of human contact aid or inhibit the spread of diseases such as HIV in a population. The evolution of social networks can sometimes be modeled by the use of agent based models, providing insight into the interplay between communication rules, rumor spreading and social structure.

SNA may also be an effective tool for mass surveillance -- for example the Total Information Awareness program was doing in-depth research on strategies to analyze social networks to determine whether or not U.S. citizens were political threats.

Diffusion of innovations theory explores social networks and their role in influencing the spread of new ideas and practices. Change agents and opinion leaders often play major roles in spurring the adoption of innovations, although factors inherent to the innovations also play a role.

Robin Dunbar has suggested that the typical size of an egocentric network is constrained to about 150 members due to possible limits in the capacity of the human communication channel. The rule arises from cross-cultural studies in sociology and especially anthropology of the maximum size of a village (in modern parlance most reasonably understood as an ecovillage). It is theorized in evolutionary psychology that the number may be some kind of limit of average human ability to recognize members and track emotional facts about all members of a group. However, it may be due to economics and the need to track "free riders", as it may be easier in larger groups to take advantage of the benefits of living in a community without contributing to those benefits.

Mark Granovetter found in one study that more numerous weak ties can be important in seeking information and innovation. Cliques have a tendency to have more homogeneous opinions as well as share many common traits. This homophilic tendency was the reason for the members of the cliques to be attracted together in the first place. However, being similar, each member of the clique would also know more or less what the other members knew. To find new information or insights, members of the clique will have to look beyond the clique to its other friends and acquaintances. This is what Granovetter called "the strength of weak ties".

Guanxi is a central concept in Chinese society (and other East Asian cultures) that can be summarized as the use of personal influence. Guanxi can be studied from a social network approach.[13]

The small world phenomenon is the hypothesis that the chain of social acquaintances required to connect one arbitrary person to another arbitrary person anywhere in the world is generally short. The concept gave rise to the famous phrase six degrees of separation after a 1967 small world experiment by psychologist Stanley Milgram. In Milgram's experiment, a sample of US individuals were asked to reach a particular target person by passing a message along a chain of acquaintances. The average length of successful chains turned out to be about five intermediaries or six separation steps (the majority of chains in that study actually failed to complete). The methods (and ethics as well) of Milgram's experiment was later questioned by an American scholar, and some further research to replicate Milgram's findings had found that the degrees of connection needed could be higher.[14] Academic researchers continue to explore this phenomenon as Internet-based communication technology has supplemented the phone and postal systems available during the times of Milgram. A recent electronic small world experiment at Columbia University found that about five to seven degrees of separation are sufficient for connecting any two people through e-mail.[15]

Collaboration graphs can be used to illustrate good and bad relationships between humans. A positive edge between two nodes denotes a positive relationship (friendship, alliance, dating) and a negative edge between two nodes denotes a negative relationship (hatred, anger). Signed social network graphs can be used to predict the future evolution of the graph. In signed social networks, there is the concept of "balanced" and "unbalanced" cycles. A balanced cycle is defined as a cycle where the product of all the signs are positive. Balanced graphs represent a group of people who are unlikely to change their opinions of the other people in the group. Unbalanced graphs represent a group of people who are very likely to change their opinions of the people in their group. For example, a group of 3 people (A, B, and C) where A and B have a positive relationship, B and C have a positive relationship, but C and A have a negative relationship is an unbalanced cycle. This group is very likely to morph into a balanced cycle, such as one where B only has a good relationship with A, and both A and B have a negative relationship with C. By using the concept of balances and unbalanced cycles, the evolution of signed social network graphs can be predicted.

One study has found that happiness tends to be correlated in social networks. When a person is happy, nearby friends have a 25 percent higher chance of being happy themselves. Furthermore, people at the center of a social network tend to become happier in the future than those at the periphery. Clusters of happy and unhappy people were discerned within the studied networks, with a reach of three degrees of separation: a person's happiness was associated with the level of happiness of their friends' friends' friends.[16] (See also Emotional contagion.)

Some researchers have suggested that human social networks may have a genetic basis.[17] Using a sample of twins from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, they found that in-degree (the number of times a person is named as a friend), transitivity (the probability that two friends are friends with one another), and betweenness centrality (the number of paths in the network that pass through a given person) are all significantly heritable. Existing models of network formation cannot account for this intrinsic node variation, so the researchers propose an alternative "Attract and Introduce" model that can explain heritability and many other features of human social networks.[18]

Application to Environmental Issues

The 1984 book The IRG Solution argued that central media and government-type hierarchical organizations could not adequately understand the environmental crisis we were manufacturing, or how to initiate adequate solutions. It argued that the widespread introduction of Information Routing Groups was required to create a social network whose overall intelligence could collectively understand the issues and devise and implement correct workeable solutions and policies.

Metrics (Measures) in social network analysis

- Betweenness

- The extent to which a node lies between other nodes in the network. This measure takes into account the connectivity of the node's neighbors, giving a higher value for nodes which bridge clusters. The measure reflects the number of people who a person is connecting indirectly through their direct links.[19]

- Bridge

- An edge is said to be a bridge if deleting it would cause its endpoints to lie in different components of a graph.

- Centrality

- This measure gives a rough indication of the social power of a node based on how well they "connect" the network. "Betweenness", "Closeness", and "Degree" are all measures of centrality.

- Centralization

- The difference between the number of links for each node divided by maximum possible sum of differences. A centralized network will have many of its links dispersed around one or a few nodes, while a decentralized network is one in which there is little variation between the number of links each node possesses.

- Closeness

- The degree an individual is near all other individuals in a network (directly or indirectly). It reflects the ability to access information through the "grapevine" of network members. Thus, closeness is the inverse of the sum of the shortest distances between each individual and every other person in the network. (See also: Proxemics) The shortest path may also be known as the "geodesic distance".

- Clustering coefficient

- A measure of the likelihood that two associates of a node are associates themselves. A higher clustering coefficient indicates a greater 'cliquishness'.

- Cohesion

- The degree to which actors are connected directly to each other by cohesive bonds. Groups are identified as ‘cliques’ if every individual is directly tied to every other individual, ‘social circles’ if there is less stringency of direct contact, which is imprecise, or as structurally cohesive blocks if precision is wanted.[20]

- Degree

- The count of the number of ties to other actors in the network. See also degree (graph theory).

- (Individual-level) Density

- The degree a respondent's ties know one another/ proportion of ties among an individual's nominees. Network or global-level density is the proportion of ties in a network relative to the total number possible (sparse versus dense networks).

- Flow betweenness centrality

- The degree that a node contributes to sum of maximum flow between all pairs of nodes (not that node).

- Eigenvector centrality

- A measure of the importance of a node in a network. It assigns relative scores to all nodes in the network based on the principle that connections to nodes having a high score contribute more to the score of the node in question.

- Local Bridge

- An edge is a local bridge if its endpoints share no common neighbors. Unlike a bridge, a local bridge is contained in a cycle.

- Path Length

- The distances between pairs of nodes in the network. Average path-length is the average of these distances between all pairs of nodes.

- Prestige

- In a directed graph prestige is the term used to describe a node's centrality. "Degree Prestige", "Proximity Prestige", and "Status Prestige" are all measures of Prestige. See also degree (graph theory).

- Radiality

- Degree an individual’s network reaches out into the network and provides novel information and influence.

- Reach

- The degree any member of a network can reach other members of the network.

- Structural cohesion

- The minimum number of members who, if removed from a group, would disconnect the group.[21]

- Structural equivalence

- Refers to the extent to which nodes have a common set of linkages to other nodes in the system. The nodes don’t need to have any ties to each other to be structurally equivalent.

- Structural hole

- Static holes that can be strategically filled by connecting one or more links to link together other points. Linked to ideas of social capital: if you link to two people who are not linked you can control their communication.

Network analytic software

Network analytic tools are used to represent the nodes (agents) and edges (relationships) in a network, and to analyze the network data. Like other software tools, the data can be saved in external files. Additional information comparing the various data input formats used by network analysis software packages is available at NetWiki. Network analysis tools allow researchers to investigate large networks like the Internet, disease transmission, etc. These tools provide mathematical functions that can be applied to the network model.

Visualization of Networks

Visual representation of social networks is important to understand the network data and convey the result of the analysis [1]. Most of the softwares have besides the analytical tools also modules for network visuaization. Exploration of the data is done through displaying nodes and ties in various layouts, and attributing colors, size and other advanced properties to nodes.

Typical representation of the network data are graphs in network layout (nodes and ties). These are not very easy-to-read and do not allow an intuitive interpretation. Various new methods have been developed in order to display network data in more intuitive format (e.g. Sociomapping).

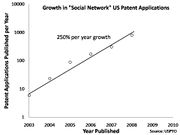

Patents

There has been rapid growth in the number of US patent applications that cover new technologies related to social networking. The number of published applications has been growing at about 250% per year over the past five years. There are now over 2000 published applications.[22] Only about 100 of these applications have issued as patents, however, largely due to the multi-year backlog in examination of business method patents and ethical issues connected with this patent category [23]

See also

|

|

References

- ↑ Linton Freeman, The Development of Social Network Analysis. Vancouver: Empirical Press, 2006.

- ↑ Wellman, Barry and S.D. Berkowitz, eds., 1988. Social Structures: A Network Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Hansen, William B. and Reese, Eric L. 2009. Network Genie User Manual. Greensboro, NC: Tanglewood Research.

- ↑ Freeman, Linton. 2006. The Development of Social Network Analysis. Vancouver: Empirical Pres, 2006; Wellman, Barry and S.D. Berkowitz, eds., 1988. Social Structures: A Network Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Scott, John. 1991. Social Network Analysis. London: Sage.

- ↑ Wasserman, Stanley, and Faust, Katherine. 1994. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ The Development of Social Network Analysis Vancouver: Empirical Press.

- ↑ A.R. Radcliffe-Brown, "On Social Structure," Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute: 70 (1940): 1-12.

- ↑ [Nadel, SF. 1957. The Theory of Social Structure. London: Cohen and West.

- ↑ The Networked Individual: A Profile of Barry Wellman

- ↑ Mark Granovetter, "Introduction for the French Reader," Sociologica 2 (2007): 1-8; Wellman, Barry. 1988. "Structural Analysis: From Method and Metaphor to Theory and Substance." Pp. 19-61 in Social Structures: A Network Approach, edited by Barry Wellman and S.D. Berkowitz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Mark Granovetter, "Introduction for the French Reader," Sociologica 2 (2007): 1-8; Wellman, Barry. 1988. "Structural Analysis: From Method and Metaphor to Theory and Substance." Pp. 19-61 in Social Structures: A Network Approach, edited by Barry Wellman and S.D. Berkowitz. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. (see also Scott, 2000 and Freeman, 2004).

- ↑ Barry Wellman, Wenhong Chen and Dong Weizhen. “Networking Guanxi." Pp. 221-41 in Social Connections in China: Institutions, Culture and the Changing Nature of Guanxi, edited by Thomas Gold, Douglas Guthrie and David Wank. Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- ↑ Could It Be A Big World After All?: Judith Kleinfeld article.

- ↑ Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age, Duncan Watts.

- ↑ James H. Fowler and Nicholas A. Christakis. 2008. "Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study." British Medical Journal. December 4, 2008: doi:10.1136/bmj.a2338. Media account for those who cannot retrieve the original: Happiness: It Really is Contagious Retrieved December 5, 2008.

- ↑ "Genes and the Friends You Make". Wall Street Journal. January 27, 2009. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB123302040874118079.html.

- ↑ Fowler, J. H.; Dawes, CT; Christakis, NA (10 February 2009). "Model of Genetic Variation in Human Social Networks" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 106 (6): 1720–1724. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806746106. PMID 19171900. PMC 2644104. http://jhfowler.ucsd.edu/genes_and_social_networks.pdf.

- ↑ The most comprehensive reference is: Wasserman, Stanley, & Faust, Katherine. (1994). Social Networks Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. A short, clear basic summary is in Krebs, Valdis. (2000). "The Social Life of Routers." Internet Protocol Journal, 3 (December): 14-25.

- ↑ Cohesive.blocking is the R program for computing structural cohesion according to the Moody-White (2003) algorithm. This wiki site provides numerous examples and a tutorial for use with R.

- ↑ Moody, James, and Douglas R. White (2003). "Structural Cohesion and Embeddedness: A Hierarchical Concept of Social Groups." American Sociological Review 68(1):103-127. Online: (PDF file.

- ↑ USPTO search on published patent applications mentioning “social network”

- ↑ USPTO search on issued patents mentioning “social network”

Further reading

- Barnes, J. A. "Class and Committees in a Norwegian Island Parish", Human Relations 7:39-58

- Berkowitz, Stephen D. 1982. An Introduction to Structural Analysis: The Network Approach to Social Research. Toronto: Butterworth. ISBN 0-409-81362-1

- Brandes, Ulrik, and Thomas Erlebach (Eds.). 2005. Network Analysis: Methodological Foundations Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag.

- Breiger, Ronald L. 2004. "The Analysis of Social Networks." Pp. 505–526 in Handbook of Data Analysis, edited by Melissa Hardy and Alan Bryman. London: Sage Publications. ISBN 0-7619-6652-8 Excerpts in pdf format

- Burt, Ronald S. (1992). Structural Holes: The Structure of Competition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-84372-X

- (Italian) Casaleggio, Davide (2008). TU SEI RETE. La Rivoluzione del business, del marketing e della politica attraverso le reti sociali. ISBN 88-901826-5-2

- Carrington, Peter J., John Scott and Stanley Wasserman (Eds.). 2005. Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80959-7

- Christakis, Nicholas and James H. Fowler "The Spread of Obesity in a Large Social Network Over 32 Years," New England Journal of Medicine 357 (4): 370-379 (26 July 2007)

- Doreian, Patrick, Vladimir Batagelj, and Anuska Ferligoj. (2005). Generalized Blockmodeling. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84085-6

- Freeman, Linton C. (2004) The Development of Social Network Analysis: A Study in the Sociology of Science. Vancouver: Empirical Press. ISBN 1-59457-714-5

- Hill, R. and Dunbar, R. 2002. "Social Network Size in Humans." Human Nature, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 53–72.

- Jackson, Matthew O. (2003). "A Strategic Model of Social and Economic Networks". Journal of Economic Theory 71: 44–74. doi:10.1006/jeth.1996.0108. pdf

- Huisman, M. and Van Duijn, M. A. J. (2005). Software for Social Network Analysis. In P J. Carrington, J. Scott, & S. Wasserman (Editors), Models and Methods in Social Network Analysis (pp. 270–316). New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80959-7

- Krebs, Valdis (2006) Social Network Analysis, A Brief Introduction. (Includes a list of recent SNA applications Web Reference.)

- Ligon, Ethan; Schechter, Laura, "The Value of Social Networks in rural Paraguay", University of California, Berkeley, Seminar, March 25, 2009 , Department of Agricultural & Resource Economics, College of Natural Resources, University of California, Berkeley

- Lima, Francisco W. S., Hadzibeganovic, Tarik, and Dietrich Stauffer (2009). Evolution of ethnocentrism on undirected and directed Barabási-Albert networks. Physica A, 388(24), 4999-5004.

- Lin, Nan, Ronald S. Burt and Karen Cook, eds. (2001). Social Capital: Theory and Research. New York: Aldine de Gruyter. ISBN 0-202-30643-7

- Mullins, Nicholas. 1973. Theories and Theory Groups in Contemporary American Sociology. New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-044649-8

- Müller-Prothmann, Tobias (2006): Leveraging Knowledge Communication for Innovation. Framework, Methods and Applications of Social Network Analysis in Research and Development, Frankfurt a. M. et al.: Peter Lang, ISBN 0-8204-9889-0.

- Manski, Charles F. (2000). "Economic Analysis of Social Interactions". Journal of Economic Perspectives 14: 115–36. doi:10.1257/jep.14.3.115. [2] via JSTOR

- Moody, James, and Douglas R. White (2003). "Structural Cohesion and Embeddedness: A Hierarchical Concept of Social Groups." American Sociological Review 68(1):103-127. [3]

- Newman, Mark (2003). "The Structure and Function of Complex Networks". SIAM Review 56: 167–256. doi:10.1137/S003614450342480. pdf

- Nohria, Nitin and Robert Eccles (1992). Networks in Organizations. second ed. Boston: Harvard Business Press. ISBN 0-87584-324-7

- Nooy, Wouter d., A. Mrvar and Vladimir Batagelj. (2005). Exploratory Social Network Analysis with Pajek. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-84173-9

- Scott, John. (2000). Social Network Analysis: A Handbook. 2nd Ed. Newberry Park, CA: Sage. ISBN 0-7619-6338-3

- Sethi, Arjun. (2008). Valuation of Social Networking [4]

- Tilly, Charles. (2005). Identities, Boundaries, and Social Ties. Boulder, CO: Paradigm press. ISBN 1-59451-131-4

- Valente, Thomas W. (1995). Network Models of the Diffusion of Innovations. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press. ISBN 1-881303-21-7

- Wasserman, Stanley, & Faust, Katherine. (1994). Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-38269-6

- Watkins, Susan Cott. (2003). "Social Networks." Pp. 909–910 in Encyclopedia of Population. rev. ed. Edited by Paul George Demeny and Geoffrey McNicoll. New York: Macmillan Reference. ISBN 0-02-865677-6

- Watts, Duncan J. (2003). Small Worlds: The Dynamics of Networks between Order and Randomness. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-11704-7

- Watts, Duncan J. (2004). Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-32542-3

- Wellman, Barry (1998). Networks in the Global Village: Life in Contemporary Communities. Boulder, CO: Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-1150-0

- Wellman, Barry. 2001. "Physical Place and Cyber-Place: Changing Portals and the Rise of Networked Individualism." International Journal for Urban and Regional Research 25 (2): 227-52.

- Wellman, Barry and Berkowitz, Stephen D. (1988). Social Structures: A Network Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-24441-2

- Weng, M. (2007). A Multimedia Social-Networking Community for Mobile Devices Interactive Telecommunications Program, Tisch School of the Arts/ New York University

- White, Harrison, Scott Boorman and Ronald Breiger. 1976. "Social Structure from Multiple Networks: I Blockmodels of Roles and Positions." American Journal of Sociology 81: 730-80.

External links

- Social Networking at the Open Directory Project

- The International Network for Social Network Analysis (INSNA) - professional society of social network analysts, with more than 1,000 members

- Center for Computational Analysis of Social and Organizational Systems (CASOS) at Carnegie Mellon

- NetLab at the University of Toronto, studies the intersection of social, communication, information and computing networks

- Netwiki (wiki page devoted to social networks; maintained at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

- Building networks for learning- A guide to on-line resources on strengthening social networking.

- Program on Networked Governance - Program on Networked Governance, Harvard University

- The International Workshop on Social Network Analysis and Mining (SNAKDD) - An annual workshop on social network analysis and mining, with participants from computer science, social science, and related disciplines.

- Historical Dynamics in a time of Crisis: Late Byzantium, 1204-1453 (a discussion of social network analysis from the point of view of historical studies)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||