Shawnee

|

| Total population |

|---|

| 14,000 (7584 enrolled)[1] |

| Regions with significant populations |

| Oklahoma[1] |

| Languages |

|

Shawnee, English |

| Religion |

|

traditional beliefs and Christianity |

| Related ethnic groups |

|

Sac and Fox (Mesquakie) |

The Shawnee, Shaawanwaki, Shaawanooki and Shaawanowi lenaweeki,[2] are an Algonquian-speaking people native to North America. Historically they inhabited the areas of Ohio, Virginia, West Virginia, Western Maryland, Kentucky, Indiana, and Pennsylvania. Today there are three federally recognized Shawnee tribes: Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, and Shawnee Tribe, all of which are headquartered in Oklahoma.

Contents |

History

Early history

The prehistoric origins of the Shawnees are uncertain. The Algonquian nations of present-day Canada regarded the Shawnee as their southernmost branch. Along the East Coast, the Algonquian-speaking tribes were mostly located in coastal areas, from Quebec to the Carolinas. Algonquian languages have words similar to the archaic shawano (now: shaawanwa) meaning "south". However, the stem shaawa- does not mean "south" in Shawnee, but "moderate, warm (of weather)". In one Shawnee tale, Shaawaki is the deity of the south.

Some scholars have speculated that the Shawnee are descendants of the people of the prehistoric Fort Ancient culture of the Ohio country, although no definitive proof has been established.[3]

Europeans reported encountering Shawnee over a widespread geographic area. The earliest mention of the Shawnee may be a 1614 Dutch map showing the Sawwanew just east of the Delaware River. Later 17th-century Dutch sources also place them in this general location. Accounts by French explorers in the same century usually located the Shawnee along the Ohio River, where they encountered them on forays from Canada and the Illinois Country.[4]

According to one legend, the Shawnee were descended from a party sent by Chief Opechancanough, ruler of the Powhatan Confederacy 1618-1644, to settle in the Shenandoah Valley. The party was led by his son, Sheewa-a-nee, for whom they were named.[5] Edward Bland, an explorer who accompanied Abraham Wood's expedition in 1650, wrote that in Opechancanough's day, there had been a falling-out between the "Chawan" chief and the weroance of the Powhatan (also a relative of Opechancanough's family). He said the latter had murdered the former.[6] Explorers Batts and Fallam in 1671 reported that the Shawnee were contesting the Shenandoah Valley with Iroquois in that year, and were losing. By the time European-American settlers began to arrive in the Valley (c. 1730), the Iroquois had departed. The Shawnee were then the sole residents of the northern part of the valley.

Sometime before 1670, a group of Shawnee migrated to the Savannah River area. The English based in Charles Town, South Carolina were contacted by these Shawnee in 1674. They forged a long-lasting alliance. The Savannah River Shawnee were known to the Carolina English as "Savannah Indians". Around the same time, other Shawnee groups migrated to Florida, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and other regions south and east of the Ohio country.

Historian Alan Gallay speculates that the Shawnee migrations of the middle to late 17th century were probably driven by the Iroquois Wars that began in the 1640s. The Shawnee became known for their widespread settlements from modern Illinois and New York to Georgia. Among their known villages were Eskippakithiki, Sonnionto, and Suwanee, Georgia. Their language became a lingua franca for trade among numerous tribes. They became leaders among the tribes, initiating and sustaining pan-Indian resistance to European and Euro-American expansion.[7]

Prior to 1754, the Shawnee had a headquarters at Shawnee Springs at modern-day Cross Junction, Virginia near Winchester. The father of the later chief Cornstalk held his court there. Two other Shawnee villages existed in the Shenandoah Valley: one at Moorefield, West Virginia, and one on the North River. In 1753, Shawnee to the west sent messengers inviting the Virginia people to leave the Shenandoah Valley and cross the Alleghenies. The Virginia Shawnee migrated west the following year,[8][9] joining Shawnee on the Scioto River in the Ohio country.

After the Beaver Wars, the Iroquois claimed the Ohio Country as their hunting ground by right of conquest, and treated the Shawnee and Delaware who resettled there as dependent tribes. Some independent Iroquois bands from various tribes also migrated westward, where they became known in Ohio as the Mingo. These three tribes — the Shawnee, the Delaware, and the Mingo — then became closely associated with one another, despite the differences in their languages. The first two were Algonguian speaking and the third Iroquoian.

Sixty Years' War

After the Battle of the Monongahela in 1755, many Shawnee fought as allies of their trading partners the French during the early years of the French and Indian War (aka Seven Years War). In 1758 they settled with the British colonists, signing the Treaty of Easton in 1758. When the British defeated the French in 1763, other Shawnee joined Pontiac's Rebellion against the British, which failed a year later.

The British issued the Royal Proclamation of 1763 during Pontiac's Rebellion, to draw a boundary line between the British colonies in the east and the Ohio Country west of the Appalachian Mountains. They were trying to settle points of conflict with the Indians and establish a reserve for them. The Treaty of Fort Stanwix in 1768, however, extended that line westwards, giving the British a claim to what is now West Virginia and Kentucky. The Shawnee did not agree to this treaty: it was negotiated between British officials and the Iroquois, who claimed sovereignty over the land, although Shawnee and other Native American tribes also hunted there.

After the Stanwix treaty, Anglo-Americans began pouring into the Ohio River Valley for settlement. Violent incidents between settlers and Indians escalated into Dunmore's War in 1774. British diplomats managed to isolate the Shawnee during the conflict: the Iroquois and the Delaware stayed neutral. The Shawnee faced the British colony of Virginia with only a few Mingo allies. Lord Dunmore, royal governor of Virginia, launched a two-pronged invasion into the Ohio Country. Shawnee Chief Cornstalk attacked one wing but fought to a draw in the only major battle of the war, the Battle of Point Pleasant.

In the Treaty of Camp Charlotte, Cornstalk and the Shawnee were compelled to recognize the Ohio River boundary established by the 1768 Stanwix treaty. Many other Shawnee leaders refused to recognize this boundary, however. When the American Revolutionary War broke out in 1776, several Shawnee chiefs advocated joining the war as British allies, hoping to drive the colonists back across the mountains. The Shawnee were divided: Cornstalk led those who wished to remain neutral, while war leaders such as Chief Blackfish and Blue Jacket fought as British allies.

After the Revolution, in the Northwest Indian War between the United States and a confederation of Native American tribes, the Shawnee combined with the Miami into a great fighting force. After the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794, most of the Shawnee bands signed the Treaty of Greenville the next year. They were forced to cede large parts of their homeland to the new United States. Other Shawnee groups rejected this treaty and migrated to Missouri, where they settled near Cape Girardeau.

War of 1812

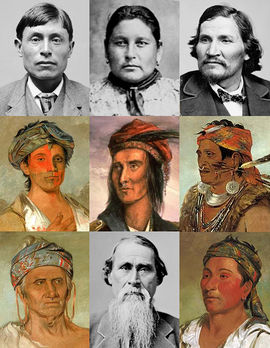

Portraits of Pushmataha (left) and Tecumseh. Pushmataha, 1811 - Sharing Choctaw History.[10] Tecumseh, 1811 - The Portable North American Indian Reader.[11] |

By 1800, only the Chillicothe and Mequachake tribes remained in Ohio, while the Hathawekela, Kispokotha, and Piqua had migrated to Missouri. From 1805, a minority of Shawnee joined the pan-tribal movement of Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa. This led to Tecumseh's War and his death at the Battle of the Thames on October 5, 1813. This was the last attempt by the Shawnee nation to defend the Ohio country from European-American expansion.

A comet, earthquakes, and Tecumseh (1811)

A comet appeared in March 1811. The Shawnee leader Tecumseh, whose name meant "shooting star,"[12] traveled throughout the Southeast where he told the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee, and many others that the comet signaled his coming. McKenney reported that the Tecumseh would prove that the Great Spirit had sent him by giving the them a sign. Shortly after Tecumseh left the Southeast, the sign arrived as promised in the form of an earthquake.

| “ | The Indians were filled with great terror ... the trees and wigwams shook exceedingly; the ice which skirted the margin of the Arkansas river was broken into pieces; and the most of the Indians thought that the Great Spirit, angry with the human race, was about to destroy the world. | ” |

|

—- Roger L. Nichols, The American Indian |

||

On December 11, 1811, the New Madrid Earthquake shook the Muscogee lands and the Midwest. While the interpretation of this event varied from tribe to tribe, one consensus was universally accepted: the powerful earthquake had to have meant something. The earthquake and its aftershocks helped the Tecumseh resistance movement by convincing, not only the Muscogee, but other Native American tribes as well, that the Shawnee must be supported.

The Muscogee who joined Tecumseh's confederation were known as the Red Sticks. Stories of the origin of the Red Stick name varies, but one is that they were named for the Muscogee tradition of carrying a bundle of sticks that mark the days until an event occurs. Sticks painted red symbol war.[13]

| “ | [Governor William Harrison,] you have the liberty to return to your own country ... you wish to prevent the Indians from doing as we wish them, to unite and let them consider their lands as common property of the whole ... You never see an Indian endeavor to make the white people do this ... Sell a country! Why not sell the air, the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children? How can we have confidence in the white people? | ” |

|

—— Tecumseh, 1810[14] |

||

After the war

The Shawnee in Missouri became known as the "Absentee Shawnee." Several hundred members of this tribe left the United States together with some Delaware to settle in the eastern part of Spanish Texas. Although closely allied with the Cherokee led by The Bowl, their chief John Linney remained neutral during the 1839 Cherokee War. In appreciation, Texan president Mirabeau Lamar fully compensated the Shawnee for their improvements and crops when funding their removal north to Arkansaw Territory.[15] The Shawnee settled close to present-day Shawnee, Oklahoma. They were joined by Shawnee from Kansas who shared their traditionalist views and beliefs.

In 1817, the Ohio Shawnee signed the Treaty of Fort Meigs, ceding their remaining lands in exchange for three reservations in Wapaughkonetta, Hog Creek (near Lima) and Lewistown, Ohio. They shared these lands with the Seneca.

Missouri joined the Union in 1821. After the Treaty of St. Louis in 1825, the 1,400 Missouri Shawnees were forcibly relocated from Cape Girardeau to southeastern Kansas, close to the Neosho River.

During 1833, only Black Bob's band of Shawnee resisted removal. They settled in northeastern Kansas near Olathe and along the Kansas (Kaw) River in Monticello near Gum Springs. The Shawnee Methodist Mission was built nearby to minister to the tribe. About 200 of the Ohio Shawnee followed the Prophet Tenskwatawa and joined their Kansas brothers and sisters in 1826.

The main body followed Black Hoof, who fought every effort to force the Shawnee to give up the Ohio homeland. In 1831, the Lewistown group of Seneca-Shawnee left for the Indian territory (present-day Oklahoma). After the death of Black Hoof, the remaining 400 Ohio Shawnee in Wapaughkonetta and Hog Creek surrendered their land and moved to the Shawnee Reserve in Kansas.

During the American Civil War, Black Bob's band fled from Kansas and joined the "Absentee Shawnee" in Oklahoma to escape the war. After the Civil War, the Shawnee in Kansas were expelled and forced to move to northeastern Oklahoma. The Shawnee members of the former Lewistown group became known as the "Eastern Shawnee".

The former Kansas Shawnee became known as the "Loyal Shawnee" (some say this is because of their allegiance with the Union during the war; others say this is because they were the last group to leave their Ohio homelands). The latter group was regarded as part of the Cherokee Nation by the United States because they were also known as the "Cherokee Shawnee". In 2000 the "Loyal" or "Cherokee" Shawnee finally received federal recognition independent of the Cherokee Nation. They are now known as the "Shawnee Tribe". Today, most of the members of the Shawnee nation still reside in Oklahoma.

Groups

Before contact with Europeans, the Shawnee tribe consisted of a loose confederacy of five divisions which shared a common language and culture. The division names have been spelled in a variety of ways.[16] The divisions are:

- Chillicothe (Principal Place),Chalahgawtha, Chalaka, Chalakatha;

- Hathawekela, Thawikila;

- Kispoko,Kispokotha, Kishpoko, Kishpokotha;

- Mekoche,Mequachake, Machachee, Maguck, Mackachack, etc.;

- Pekowi,Pekuwe, Piqua, Pekowitha.

In addition to the five divisions, the Shawnee can be divided into six clans or subdivisons.[17] Each name group is common among each for the five divisions and each Shawnee belongs to a group.[17] The six group names are:

- Pellewomhsoomi (Turkey name group)- represents bird life,

- Kkahkileewomhsoomi (Turtle name group)- represents aquatic life,

- Petekoθiteewomhsoomi (Rounded-feet name group)- represents carnivorous animals like the dog, wolf, or whose paws are ball-shaped or "rounded,"

- Mseewiwomhsoomi (Horse name group)- represents herbivorous animals as the horse and deer,

- θepatiiwomhsoomi (Raccoon name group), represents aniamls having paws which can rip and tear like those of a raccon and bear.

- Petakineeθiiwomhsoomi (Rabbit name group), represents a gentle and peaceful nature.[17]

Membership in a division was inherited from the father, unlike the matrilineal descent often associated with other tribes. Each division had a primary village where the chief of the division lived. This village was usually named after the division. By tradition, each Shawnee division had certain roles it performed on behalf of the entire tribe. By the time they were recorded in writing by European-Americans, these strong social traditions were fading. They remain poorly understood. Because of the scattering of the Shawnee people from the 17th century through the 19th century, the roles of the divisions changed.

Today there are three federally recognized tribes in the United States, all of which are located in Oklahoma:

- The Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma, consisting mainly of Hathawekela, Kispokotha, and Pekuwe;

- The Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma, mostly of the Mekoche division; and

- The Shawnee Tribe, formerly an official part of the Cherokee Nation, mostly of the Chaalakatha and Mekoche divisions.

As of 2008, there were 7584 enrolled Shawnee, with most living in Oklahoma.[18]

Shawnee in Ohio and other states

At least four bands of Shawnee reside in Ohio:

- the Blue Creek Band,

- the East of the River Shawnee,

- the Piqua Shawnee Tribe - officially recognized in Alabama by proclamation, and in Ohio by Ohio Senate Resolution 188, adopted February 26, 1991 and by the Ohio House of Representatives 119th General Assembly Resolution No. 83, adopted April 3, 1991 as presented to the Bureau of Indian Affairs Washington D.C., and in Kentucky by Govenor's Proclamation dated August 13, 1991

- the United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation[19]

These bands are not federally recognized. "Joint Resolution to recognize the Shawnee Nation United Remnant Band" as adopted by the [Ohio] Senate, 113th General Assembly, Regular Session, Am. Sub. H.J.R. No. 8, 1979-1980</ref>, though some legal scholars dispute the formality of this recognition.[20]

Other bands residing in Ohio, Kentucky and Alabama.

In 2010 the Ridgetop Shawnee Tribe of Indians were named as an official State Recognized Tribe in Kentucky. The Ridgetop Shawnee Tribe of Indians were recognized by a 97-0 vote in the Kentucky State House. [21] .[22] [23]

The Piqua Shawnee Tribe are officially recognized in Alabama by proclamation, and in Ohio by Ohio Senate Resolution 188, adopted February 26, 1991 and by the Ohio House of Representatives 119th General Assembly Resolution No. 83, adopted April 3, 1991 as presented to the Bureau of Indian Affairs Washington D.C., and in Kentucky by Govenor's Proclamation dated August 13, 1991 [24][25]

Flags of the Shawnee

|

Flag of the Absentee-Shawnee Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma |

Flag of the Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma |

Flag of the Shawnee Tribe |

Flag of the United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation |

Coins of the Shawnee

|

First coin issue of 2002 - one dollar |

Tecumseh commemorative dollar |

Famous Shawnee

- Cornstalk (1720–1777), led the Shawnee in Dunmore's War,

- Blue Jacket (1743–1810), also known as Weyapiersenwah, was an important predecessor to Tecumseh and a leader in the Northwest Indian War.

- Black Hoof (1740–1831), also known as Catecahassa, was a respected Shawnee chief who believed the Shawnee had to adapt to European-American culture to survive.

- Chiksika (1760–1792), Kispoko war chief and older brother of Tecumseh

- Tecumseh (1768–1813), outstanding Shawnee leader, and his brother Tenskwatawa attempted to unite the Eastern tribes against the expansion of European-American settlement.\

- Tenskwatawa (1775–1836), Shawnee prophet and younger brother of Tecumseh

- Black Bob, 19th c. leader and warrior

- Tall Eagle (Sat-Okh) (1920–2003), Polish-Shawnee Canadian, fought in WWII, novelist

- Nas'Naga (1941- ), American Shawnee novelist and poet.

See also

- Shawnee language

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Oklahoma Indian Affairs Commission. Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial. 2008.

- ↑ Shawano was an archaic name for the tribes bearing this generic name Shaawanwa lenaki. Reference: Shawnee Traditions

- ↑ O'Donnell, James H. Ohio's First Peoples, p. 31. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8214-1525-5 (paperback), ISBN 0-8214-1524-7 (hardcover), also: Howard, James H. Shawnee!: The Ceremonialism of a Native Indian Tribe and its Cultural Background, p. 1. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-8214-0417-2; ISBN 0-8214-0614-0 (pbk.), and the unpublished dissertation Schutz, Noel W. Jr.: The Study of Shawnee Myth in an Ethnographic and Ethnohistorical Perspective, Ph.D. Dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Indiana University, 1975.

- ↑ Charles Augustus Hanna, 1911 The Wilderness Trail, esp. chap. IV, "The Shawnees", pp. 119-160.

- ↑ Carrie Hunter Willis and Etta Belle Walker, Legends of the Skyline Drive and the Great Valley of Virginia, 1937, pp. 15-16.

- ↑ Edward Bland, The Discoverie of New Brittaine,

- ↑ Gallay, Alan. The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South, 1670-1717, p. 55. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-300-10193-7

- ↑ Legends of the Skyline Drive and the Great Valley of Virginia, pp. 16-17.

- ↑ Joseph Doddridge, 1850, A History of the Valley of Virginia, p. 44

- ↑ Jones, Charile; Mike Bouch (November 1987). "Sharing Choctaw History". University of Minnesota. http://www.tc.umn.edu/~mboucher/mikebouchweb/choctaw/push1.htm. Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ Turner III, Frederick (1978). "Poetry and Oratory". The Portable North American Indian Reader. Penguin Book. pp. 246–247. ISBN 0-14-015077-3.

- ↑ Sugden, John. "The Shooting Star.' New York Times: Books. 1997 (retrieved 5 Dec 2009)

- ↑ "The Creeks." War of 1812" People and Stories. (retrieved 5 Dec 2009)

- ↑ Turner III, Frederick. "Poetry and Oratory". The Portable North American Indian Reader. Penguin Book. pp. 245–246. ISBN 0-14-015077-3.

- ↑ Lipscomb, Carol A.: "SHAWNEE INDIANS" from the Handbook of Texas Online. Retrieved 21 Feb 2010.

- ↑ Sugden, John (1997). "The Panther and the Turtle". Tecumseh: A Life. Henry Holt and Company, LLC.. p. 13. ISBN 0805061215. http://books.google.com/books?id=M5u-9OY8A0AC&printsec=frontcover&dq=tecumseh&source=bl&ots=hTqLRDHv7u&sig=jH3ugFWebYmOlRD0Ac0fm7KSQsQ&hl=en&ei=GDliTOKyNcT38Aao0MT2CQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CCgQ6AEwATgK#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Voegellin, C.F. and Voegelin, E. W. (1935). Shawnee Name Groups. American Anthropologist. pp. 617–635. 1525/aa.1935.37.4.02a00070. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1525/aa.1935.37.4.02a00070/abstract.

- ↑ Oklahoma Indian Commission. Oklahoma Indian Nations Pocket Pictorial. 2008

- ↑ "American Indians in Ohio", Ohio Memory: An Online Scrapbook of Ohio History, The Ohio Historical Society, retrieved September 30, 2007

- ↑ Watson, Blake A.. "Indian Gambling in Ohio:What are the Odds?" (PDF). Capital University Law Review 237 (2003) (excerpts). http://www.westgov.org/wga/meetings/gaming/watson-ohio.pdf. Retrieved 2007-09-30. "Ohio in any event does not officially recognize Indian tribes." Watson cites legal opinions that the resolution by the Ohio Legislature recognizing the United Remnant Band of the Shawnee Nation was ceremonial and did not grant legal status as a tribe.

- ↑ General Assembly, Kentucky (2009-feb-2009), "House Joint Resolution 15 - 2009 session of the Kentucky General Assembly", None, http://www.lrc.ky.gov/record/09RS/HJ15.htm

- ↑ manuals.chfs.ky.gov, manuals.chfs.ky.gov (2010-aug-2010), "Indian Child Welfare Act Compliance Desk Aid For Kentucky Child Welfare Workers", none, http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:h0ffCH-3o38J:manuals.chfs.ky.gov/dcbs_manuals/dpp/docs/Indian%2520Child%2520Welfare%2520Act%2520Compliance%2520Desk%2520Aid.doc+ridgetop+shawnee+recognized&cd=9&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us

- ↑ Tara Metts, Metts (2010-aug-2010), "National Indian Child Welfare Association (NICWA) and its implications in Kentucky", Citizen Foster Care Review Board, http://courts.ky.gov/aoc/juvenile/recentnewsletter.htm

- ↑ Alabama Indian Affairs Commission

- ↑ Koenig, Alexa; Jonathan Stein. [http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=alexa_koenig "Federalism and the State Recognition of Native American Tribes: A Survey of State-Recognized Tribes and State Recognition Processes Across the United States"]. Santa Clara Law Review Volume 48 (forthcoming). pp. Section 12. Ohio. http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1000&context=alexa_koenig. Retrieved 2007-09-30. "Ohio recognizes one state tribe, the United Remnant Band. . . . Ohio does not have a detailed scheme for regulating tribal-state relations."

References

- Callender, Charles. "Shawnee", in Northeast: Handbook of North American Indians, vol. 15, ed. Bruce Trigger. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 1978. ISBN 0-16-072300-0

- Clifton, James A. Star Woman and Other Shawnee Tales. Lanham, MD: University Press of America, 1984. ISBN 0-8191-3712-X; ISBN 0-8191-3713-8 (pbk.)

- Edmunds, R. David. The Shawnee Prophet. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1983. ISBN 0-8032-1850-8.

- Edmunds, R. David. Tecumseh and the Quest for Indian Leadership. Originally published 1984. 2nd edition, New York: Pearson Longman, 2006. ISBN 0-321-04371-5

- Edmunds, R. David. "Forgotten Allies: The Loyal Shawnees and the War of 1812" in David Curtis Skaggs and Larry L. Nelson, eds., The Sixty Years' War for the Great Lakes, 1754–1814, pp. 337–51. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2001. ISBN 0-87013-569-4.

- Howard, James H. Shawnee!: The Ceremonialism of a Native Indian Tribe and its Cultural Background. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1981. ISBN 0-8214-0417-2; ISBN 0-8214-0614-0 (pbk.)

- O'Donnell, James H. Ohio's First Peoples. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 2004. ISBN 0-8214-1525-5 (paperback), ISBN 0-8214-1524-7 (hardcover).

- Sugden, John. Tecumseh: A Life. New York: Holt, 1997. ISBN 0-8050-4138-9 (hardcover); ISBN 0-8050-6121-5 (1999 paperback).

- Sugden, John. Blue Jacket: Warrior of the Shawnees. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2000. ISBN 0-8032-4288-3.

External links

- Absentee Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- East Of The River Shawnee

- Shawnee History

- Shawnee Indian Mission

- Shawnee Nation URB

- "Shawnee Indian Tribe", Access Genealogy

- Treaty of Fort Meigs, 1817, Central Michigan State University

- Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- The Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma

- BlueJacket