Salic law

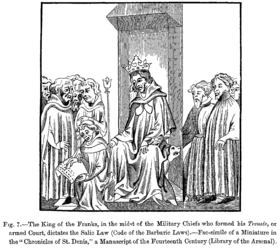

Salic law (Lat. Lex Salica) was a body of traditional law codified for governing the Salian Franks in the early Middle Ages during the reign of King Clovis I in the 6th century. Although Salic Law reflects very ancient usage and practices, the Lex Salica likely was first compiled only sometime between 507 and 511.[1]

The best-known tenet of Salic law is agnatic succession, the rule excluding females from the inheritance of a throne or fief. Indeed, "Salic law" has often been used simply as a synonym for agnatic succession. But the importance of Salic law extends beyond the rules of inheritance, as it is a direct ancestor of the systems of law in many parts of Europe today.

Contents |

General law

The law of Charlemagne was based on Salic Law, an influence as great as that of Greece and Rome. Through that connection, Salic law has had a formative influence on the tradition of statute law that has extended since then to modern times in Central Europe, especially in the German states, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, parts of Italy, Austria and Hungary, Romania, and the Balkans.

The Salic Law codified inheritance, crime, and murder. In a kingdom with many ethnic groups, each expected to be governed under its own law. The detailed laws established damages to be paid and fines levied in recompense of injuries to persons and damage to goods, e.g., slaves, theft, and unproved insults. One-third of the fine paid court costs. Judicial interpretation was by a jury of peers. These laws and their interpretations grant insight to Frankish society; Salic Law establishes that an individual person is legally unprotected by law if he or she does not belong to a family.

The most formative (geo-)political aspect of Salic inheritance law for Europe's history was its equal division of land amongst all living male children in opposition to primogeniture. This caused not only the break-up of the Carolingian Empire amongst Charlemagne's grandsons (under the Treaty of Verdun), but many kingdoms during the medieval period.

Agnatic succession

Salic law regulates succession according to sex. Agnatic succession means succession to the throne or fief going to an agnate of the predecessor; for example, a brother, a son, or nearest male relative through the male line, including collateral agnate branches, for example very distant cousins. Chief forms are agnatic seniority and agnatic primogeniture. The latter, which has been the most usual, means succession going to the eldest son of the monarch; if the monarch had no sons, the throne would pass to the nearest male relative in the male line.

Female inheritance

One provision of Salic law continued to play a role in European politics during the Middle Ages and beyond. Concerning the inheritance of land, Salic Law said

- But of Salic land no portion of the inheritance shall come to a woman: but the whole inheritance of the land shall come to the male sex.[2]

or, another transcript:

- concerning terra Salica no portion or inheritance is for a woman but all the land belongs to members of the male sex who are brothers.

As actually interpreted by the Salian Franks, the law simply prohibited women from inheriting, not all property (such as movables), but ancestral "Salic land"; and under Chilperic I sometime around the year 570, the law was actually amended to permit inheritance of land by a daughter if a man had no surviving sons. (This amendment, depending on how it is applied and interpreted, offers the basis for either Semi-Salic succession or male-preferred primogeniture, or both.)

The wording of the law, as well as usual usages in those days and centuries afterwards, seems to support an interpretation that inheritance is divided between brothers. And, if it is intended to govern succession, it can be interpreted to mandate agnatic seniority, not a direct primogeniture.

In its use by hereditary monarchies since the 15th century, aiming at agnatic succession, the Salic law is regarded as excluding all females from the succession as well as prohibiting succession rights to transfer through any woman. At least two systems of hereditary succession are direct and full applications of the Salic Law: agnatic seniority and agnatic primogeniture.

The so-called Semi-Salic version of succession order stipulates that firstly all male descendance is applied, including all collateral male lines; but if all agnates become extinct, then the closest heiress (such as a daughter) of the last male holder of the property inherits, and after her, her own male heirs according to the Salic order. In other words, the female closest to the last incumbent is regarded as a male for the purposes of inheritance/succession. This is a pragmatic way of putting order: the female is the closest, thus continuing the most recent incumbent's blood, and not involving any more distant relative than necessary. At that order, the original primogeniture is not followed with regard to the requisite female. She could be a child of a relatively junior branch of the whole dynasty, but still inherits thanks to the longevity of her own branch.

From the Middle Ages, we have one practical system of succession in cognatic male primogeniture, which actually fulfills apparent stipulations of original Salic law: succession is allowed also through female lines, but excludes the females themselves in favour of their sons. For example, a grandfather, without sons, is succeeded by his grandson, a son of his daughter, when the daughter in question is still alive. Or an uncle, without his own children, is succeeded by his nephew, a son of his sister, when the sister in question is still alive.

Strictly seen, this fulfills the Salic condition of "no land comes to a woman, but the land comes to the male sex". This can be called a Quasi-Salic system of succession and it should be classified as primogenitural, cognatic, and male.

Application in France

In 1316, King John I the Posthumous died, and for the first time in the history of the House of Capet, a king's closest living relative upon his death was not his son. French lords (notably led by the late king's uncle, Philip of Poitiers, the beneficiary of their position) wanted to forbid inheritance by a woman. These lords wanted to favour Philip's claim over John's half-sister Joan (later Joan II of Navarre), but disqualify her future claim to the French throne, and any possible future claims of Edward III of England. These events later led to the Hundred Years' War (1337–1453).

In 1328, a further limitation was needed, to bar inheritance by a male through a female line. A number of excuses were given for these applications of succession, such as "genealogical proximity with the king Saint Louis"; the role of monarch as war leader; and barring the realm going to an alien man and his clan through a woman, which also denied an order of succession where an alien man could become king of France by marriage to its queen, without necessarily having any French blood himself. Also, in 1316 the rival heir was a five-year-old female and powerless compared with the rival. In 1328, the rival was the king of England, against which France had been in a state of intermittent war for over 200 years. As far as can be ascertained, Salic law was not explicitly mentioned.

Jurists later resurrected the long-defunct Salic law and reinterpreted it to justify the line of succession arrived at in the cases of 1316 and 1328 by forbidding not only inheritance by a woman but also inheritance through a female line (In terram Salicam mulieres ne succedant).

Notwithstanding Salic law, when Francis II of Brittany died in 1488 without male issue, his daughter Anne succeeded him and ruled as duchess of Brittany until her death in 1514. (Brittany had been inherited by women earlier – Francis's own dynasty obtained the duchy through their ancestress Duchess Constance of Brittany in the 12th century.) Francis's own family, the Montfort branch of the ducal house, had obtained Brittany in the 1350s on the basis of agnatic succession, and at that time, their succession was limited to the male line only.

This law was by no means intended to cover all matters of inheritance — for example, not the inheritance of movables – only those land considered "Salic" — and there is still debate as to the legal definition of this word, although it is generally accepted to refer to lands in the royal fisc. Only several hundred years later, under the Direct Capetian kings of France and their English contemporaries who held lands in France, did Salic law become a rationale for enforcing or debating succession. By then somewhat anachronistic (there were no Salic lands, since the Salian monarchy and its lands had originally emerged in what is now the Netherlands), the idea was resurrected by Philip V in 1316 to support his claim to the throne by removing his niece Jeanne from the succession, following the death of his nephew John.

In 1328, at latest, the Salic Law needed a further interpretation to forbid not only inheritance by a woman, but inheritance through a female line, in order to bar the male Edward III of England, descendant of French kings through his mother Isabel of France, from the succession. When the Direct Capetian line ended, the law was contested by England, providing a putative motive for the Hundred Years' War.

Shakespeare claims that Charles VI rejected Henry V's claim to the French throne on the basis of Salic law's inheritance rules, leading to the Battle of Agincourt. In fact, the conflict between Salic law and English law was a justification for many overlapping claims between the French and English monarchs over the French Throne.

Other examples of the application of Salic inheritance laws

A number of military conflicts in European history have stemmed from the application of, or disregard for, Salic law. The Carlist Wars occurred in Spain over the question of whether the heir to the throne should be a female or a male relative. The War of the Austrian Succession was triggered by the Pragmatic Sanction in which Charles VI of Austria, who himself had inherited the Austrian patrimony over his nieces as a result of Salic law, attempted to ensure the inheritance directly to his own daughter Maria Theresa of Austria, this being an example of an operation of the Semi-Salic law.

In the modern kingdom of Italy under the house of Savoy the succession to the throne was regulated by Salic law.

The British and Hanoverian thrones separated after the death of King William IV of the United Kingdom and of Hanover in 1837. Hanover practised the Salic law, while Britain did not. King William's niece Victoria ascended to the throne of Great Britain and Ireland, but the throne of Hanover went to William's brother Ernest, Duke of Cumberland. Salic law was also an important issue in the Schleswig-Holstein question, and played a weary prosaic day-to-day role in the inheritance and marriage decisions of common princedoms of the German states such as Saxe-Weimar, to cite a representative example. It is not much of an overstatement to say that European nobility confronted Salic issues at every turn and nuance of diplomacy, and certainly, especially when negotiating marriages, for the entire male line had to be extinguished for a land title to pass (by marriage) to a female's husband—women rulers were anathema in the German states well into the modern era.

In a similar way, the thrones of the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Grand Duchy Of Luxembourg were separated in 1890, with the succession of Princess Wilhelmina as the first Queen-regent of the Netherlands. As a remnant of Salic law, the office of the reigning monarch of the Netherlands is always formally known as 'King' even though her title may be 'Queen'. Luxembourg passed to the House of Orange-Nassau's distantly-related agnates, the House of Nassau-Weilburg. However, that house too faced extinction in the male line less than two decades later. With no other male-line agnates in the remaining branches of the House Of Nassau, Grand Duke William IV adopted a semi-salic law of succession so that he could be succeeded by his daughters.

In the Channel Islands, the only part of the former Duchy of Normandy still held by the British Crown, Queen Elizabeth II is traditionally ascribed the title of Duke of Normandy (never Duchess). The influence of Salic law is presumed to explain why she is toasted as "The Queen our Duke". The same is the case in the Duchy and County Palatine of Lancaster, in England. The loyal toast there is to "The Queen, the Duke of Lancaster".

Old Dutch Frankish

The Salic Law contains the sole direct attestations of Old Dutch. These consist mainly of loose words (Malbergse glossen), but include a full sentence[3]:

- Maltho thi afrio lito

- "I tell you: I free you, half free."

Literary references

Shakespeare uses the Salic Law as a plot device in Henry V, saying it was upheld by the French to bar Henry V’s claiming the French throne. The play Henry V begins with the Archbishop of Canterbury asking if the claim might be upheld despite the Salic Law. The Archbishop replies, That the land Salique is in Germany, between the floods of Sala and of Elbe; the law is German, not French. The Archbishop's justification for Henry's claim, which Shakespeare intentionally renders obtuse and verbose (for comedic as well as politically expedient reasons), is also erroneous, as the Salian Franks originated in the Netherlands and the peoples of Clovis I lived along the Scheldt, Belgium.

In Royal Flash, by George MacDonald Fraser, the hero, Flashman, on his marriage, is presented with the Royal Consort's portion of the Crown Jewels, and The Duchess did rather better; as ever, feeling hard done-by, he thinks, It struck me then, and it strikes me now, that the Salic Law was a damned sound idea. p. 172, Grafton paperback, 2006.

See also

- Early Germanic law

- Agnatic descent

Notes

- ↑ Fosberry, John trans, Criminal Justice through the Ages, English trans. John Fosberry. Mittalalterliches Kriminalmuseum, Rothenburg ob der Tauber, (1990 Eng. trans. 1993) p.7

- ↑ Cave, Roy and Coulson, Herbert. A Source Book for Medieval Economic History, Biblo and Tannen, New York (1965) p.336

- ↑ "The Dutch Language". Livius.org. http://www.livius.org/dutchhistory/language.html. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

References

- Cave, Roy and Coulson, Herbert. A Source Book for Medieval Economic History, Biblo and Tannen, New York (1965)

- Craig Taylor, ed., Debating the Hundred Years War. "Pour ce que plusieurs" (La Loy Salique) and "A declaration of the trew and dewe title of Henrie VIII", Camden 5th series, Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0-521-873908

- Craig Taylor, "The Salic Law and the Valois succession to the French crown", French History, 15 (2001), pp. 358–77.

- Craig Taylor, "The Salic Law, French Queenship and the Defence of Women in the Late Middle Ages", French Historical Studies, 29 (2006), pp. 543–64.

- Drew, Katherine Fischer, The laws of the Salian Franks (Pactus legis Salicae), Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press (1991), ISBN 0-8122-8256-6/ISBN 0-8122-1322-X.

- Fosberry, John trans, Criminal Justice through the Ages, trans. John Fosberry. Mittalalterliches Kriminalmuseum, Rothenburg ob der Tauber, (1990 Eng. trans. 1993)