Inductance

| Electromagnetism | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

Electricity · Magnetism

|

||||||||||||

Inductance is the property in an electrical circuit where a change in the electric current through that circuit induces an electromotive force (EMF) that opposes the change in current (See Induced EMF).

In electrical circuits, any electric current, i, produces a magnetic field and hence generates a total magnetic flux, Φ, acting on the circuit. This magnetic flux, due to Lenz's law, tends to act to oppose changes in the flux by generating a voltage (a back EMF) in the circuit that counters or tends to reduce the rate of change in the current. The ratio of the magnetic flux times turns of wire to the current is called the self-inductance, which is usually simply referred to as the inductance of the circuit. To add inductance to a circuit, electronic components called inductors are used, which consist of coils of wire to concentrate the magnetic field.

The term 'inductance' was coined by Oliver Heaviside in February 1886.[1] It is customary to use the symbol L for inductance, possibly in honour of the physicist Heinrich Lenz.[2][3]

The SI unit of inductance is the henry (H), named after American scientist and magnetic researcher Joseph Henry. 1 H = 1 Wb/A.

Contents |

Definitions

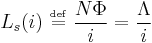

The quantitative definition of the (self-) inductance of a wire loop in SI units (webers per ampere, known as henries) is

where L is the inductance, Φ denotes the magnetic flux through the area spanned by the loop, N is the number of wire turns, and i is the current in amperes. The flux linkage thus is

.

.

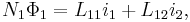

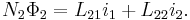

There may, however, be contributions from other circuits. Consider for example two circuits K1, K2, carrying the currents i1, i2. The flux linkages of K1 and K2 are given by

According to the above definition, L11 and L22 are the self-inductances of K1 and K2, respectively. It can be shown (see below) that the other two coefficients are equal: L12 = L21 = M, where M is called the mutual inductance of the pair of circuits.

The number of turns N1 and N2 occur somewhat asymmetrically in the definition above. However, Lmn is always proportional to the product NmNn, and thus the total currents Nmim contribute to the flux.

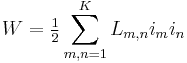

Self and mutual inductances also occur in the expression

for the energy of the magnetic field generated by K electrical circuits where in is the current in the n-th circuit. This equation is an alternative definition of inductance that also applies when the currents are not confined to thin wires, where it is not immediately clear what area is encompassed by the circuit nor how the magnetic flux through the circuit is to be defined.

The definition L = NΦ/i, in contrast, is more direct and more intuitive. It may be shown that the two definitions are equivalent by equating the time derivative of W and the electric power transferred to the system. This analysis assumes linearity, for nonlinear definitions and discussion see nonlinear inductance.

Properties of inductance

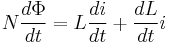

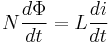

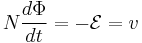

Taking the time derivative of both sides of the equation NΦ = Li yields:

In most physical cases, the inductance is constant with time and so

By Faraday's Law of Induction we have:

where  is the Electromotive force (emf) and

is the Electromotive force (emf) and  is the induced voltage. Note that the emf is opposite to the induced voltage. Thus:

is the induced voltage. Note that the emf is opposite to the induced voltage. Thus:

or

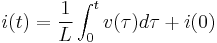

These equations together state that, for a steady applied voltage v, the current changes in a linear manner, at a rate proportional to the applied voltage, but inversely proportional to the inductance. Conversely, if the current through the inductor is changing at a constant rate, the induced voltage is constant.

The effect of inductance can be understood using a single loop of wire as an example. If a voltage is suddenly applied between the ends of the loop of wire, the current must change from zero to non-zero. However, a non-zero current induces a magnetic field by Ampère's law. This change in the magnetic field induces an emf that is in the opposite direction of the change in current. The strength of this emf is proportional to the change in current and the inductance. When these opposing forces are in balance, the result is a current that increases linearly with time where the rate of this change is determined by the applied voltage and the inductance.

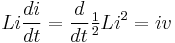

An alternative explanation of this behaviour is possible in terms of energy conservation. Multiplying the equation for di/dt above with Li leads to

Since iv is the energy transferred to the system per time it follows that (L/2)i2 is the energy of the magnetic field generated by the current. A change in current thus implies a change in magnetic field energy, and this only is possible if there also is a voltage.

A mechanical analogy is a body with mass M, velocity v and kinetic energy (M/2)v2. A change in velocity (current) requires or generates a force (an electrical voltage) proportional to mass (inductance).

Coupled inductors

Mutual inductance occurs when the change in current in one inductor induces a voltage in another nearby inductor. It is important as the mechanism by which transformers work, but it can also cause unwanted coupling between conductors in a circuit.

The mutual inductance, M, is also a measure of the coupling between two inductors. The mutual inductance by circuit i on circuit j is given by the double integral Neumann formula, see calculation techniques

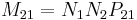

The mutual inductance also has the relationship:

where

is the mutual inductance, and the subscript specifies the relationship of the voltage induced in coil 2 to the current in coil 1.

is the mutual inductance, and the subscript specifies the relationship of the voltage induced in coil 2 to the current in coil 1.- N1 is the number of turns in coil 1,

- N2 is the number of turns in coil 2,

- P21 is the permeance of the space occupied by the flux.

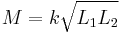

The mutual inductance also has a relationship with the coupling coefficient. The coupling coefficient is always between 1 and 0, and is a convenient way to specify the relationship between a certain orientation of inductor with arbitrary inductance:

where

- k is the coupling coefficient and 0 ≤ k ≤ 1,

- L1 is the inductance of the first coil, and

- L2 is the inductance of the second coil.

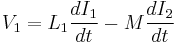

Once the mutual inductance, M, is determined from this factor, it can be used to predict the behavior of a circuit:

where

- V1 is the voltage across the inductor of interest,

- L1 is the inductance of the inductor of interest,

- dI1 / dt is the derivative, with respect to time, of the current through the inductor of interest,

- dI2 / dt is the derivative, with respect to time, of the current through the inductor that is coupled to the first inductor, and

- M is the mutual inductance.

The minus sign arises because of the sense the current I2 has been defined in the diagram. With both currents defined going into the dots the sign of M will be positive.[4]

When one inductor is closely coupled to another inductor through mutual inductance, such as in a transformer, the voltages, currents, and number of turns can be related in the following way:

where

is the voltage across the secondary inductor,

is the voltage across the secondary inductor, is the voltage across the primary inductor (the one connected to a power source),

is the voltage across the primary inductor (the one connected to a power source), is the number of turns in the secondary inductor, and

is the number of turns in the secondary inductor, and is the number of turns in the primary inductor.

is the number of turns in the primary inductor.

Conversely the current:

where

is the current through the secondary inductor,

is the current through the secondary inductor, is the current through the primary inductor (the one connected to a power source),

is the current through the primary inductor (the one connected to a power source), is the number of turns in the secondary inductor, and

is the number of turns in the secondary inductor, and is the number of turns in the primary inductor.

is the number of turns in the primary inductor.

Note that the power through one inductor is the same as the power through the other. Also note that these equations don't work if both transformers are forced (with power sources).

When either side of the transformer is a tuned circuit, the amount of mutual inductance between the two windings determines the shape of the frequency response curve. Although no boundaries are defined, this is often referred to as loose-, critical-, and over-coupling. When two tuned circuits are loosely coupled through mutual inductance, the bandwidth will be narrow. As the amount of mutual inductance increases, the bandwidth continues to grow. When the mutual inductance is increased beyond a critical point, the peak in the response curve begins to drop, and the center frequency will be attenuated more strongly than its direct sidebands. This is known as overcoupling.

Calculation techniques

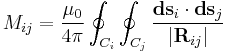

Mutual inductance

The mutual inductance by a filamentary circuit i on a filamentary circuit j is given by the double integral Neumann formula

The symbol μ0 denotes the magnetic constant (4 × 10−7 H/m),

× 10−7 H/m),  and

and  are the curves spanned by the wires,

are the curves spanned by the wires,  is the distance between two points. See a derivation of this equation.

is the distance between two points. See a derivation of this equation.

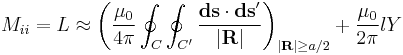

Self-inductance

Formally the self-inductance of a wire loop would be given by the above equation with i = j. However, 1/R becomes infinite and thus the finite radius a along with the distribution of the current in the wire must be taken into account. There remain the contribution from the integral over all points where |R| ≥ a/2 and a correction term,

Here a and l denote radius and length of the wire, and Y is a constant that depends on the distribution of the current in the wire: Y = 0 when the current flows in the surface of the wire (skin effect), Y = 1/4 when the current is homogenuous across the wire. This approximation is accurate when the wires are long compared to their cross-sectional dimensions. Here is a derivation of this equation.

Method of images

In some cases different current distributions generate the same magnetic field in some section of space. This fact may be used to relate self inductances (method of images). As an example consider the two systems:

- A wire at distance d/2 in front of a perfectly conducting wall (which is the return)

- Two parallel wires at distance d, with opposite current

The magnetic field of the two systems coincides (in a half space). The magnetic field energy and the inductance of the second system thus are twice as large as that of the first system.

Relation between inductance and capacitance

Inductance per length L' and capacitance per length C' are related to each other in the special case of transmission lines consisting of two parallel perfect conductors of arbitrary but constant cross section,[5]

Here ε and µ denote dielectric constant and magnetic permeability of the medium the conductors are embedded in. There is no electric and no magnetic field inside the conductors (complete skin effect, high frequency). Current flows down on one line and returns on the other. The signal propagation speed coincides with the propagation speed of electromagnetic waves in the bulk.

Self-inductance of simple electrical circuits in air

The self-inductance of many types of electrical circuits can be given in closed form. Examples are listed in the table.

| Type | Inductance /  |

Comment |

|---|---|---|

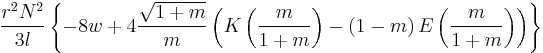

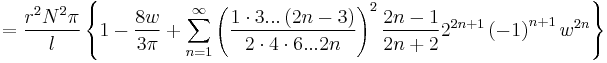

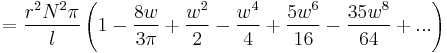

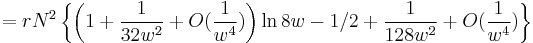

| Single layer solenoid[6] |

|

: Number of turns : Number of turnsr: Radius l: Length w = r/l   : Elliptic integrals : Elliptic integrals |

| Coaxial cable, high frequency |

|

a1: Outer radius a: Inner radius l: Length |

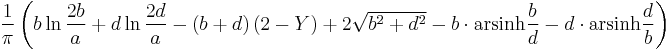

| Circular loop[7] |  |

r: Loop radius a: Wire radius |

| Rectangle |  |

b, d: Border length d >> a, b >> a a: Wire radius |

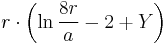

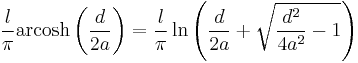

| Pair of parallel wires |

|

a: Wire radius d: Distance, d ≥ 2a l: Length of pair |

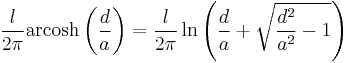

| Pair of parallel wires, high frequency |

|

a: Wire radius d: Distance, d ≥ 2a l: Length of pair |

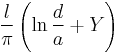

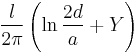

| Wire parallel to perfectly conducting wall |

|

a: Wire radius d: Distance, d ≥ a l: Length |

| Wire parallel to conducting wall, high frequency |

|

a: Wire radius d: Distance, d ≥ a l: Length |

The symbol μ0 denotes the magnetic constant (4 × 10−7 H/m). For high frequencies the electric current flows in the conductor surface (skin effect), and depending on the geometry it sometimes is necessary to distinguish low and high frequency inductances. This is the purpose of the constant Y: Y = 0 when the current is uniformly distributed over the surface of the wire (skin effect), Y = 1/4 when the current is uniformly distributed over the cross section of the wire. In the high frequency case, if conductors approach each other, an additional screening current flows in their surface, and expressions containing Y become invalid. Details for some circuit types are available on another page.

× 10−7 H/m). For high frequencies the electric current flows in the conductor surface (skin effect), and depending on the geometry it sometimes is necessary to distinguish low and high frequency inductances. This is the purpose of the constant Y: Y = 0 when the current is uniformly distributed over the surface of the wire (skin effect), Y = 1/4 when the current is uniformly distributed over the cross section of the wire. In the high frequency case, if conductors approach each other, an additional screening current flows in their surface, and expressions containing Y become invalid. Details for some circuit types are available on another page.

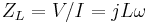

Phasor circuit analysis and impedance

Using phasors, the equivalent impedance of an inductance is given by:

where

- j is the imaginary unit,

- L is the inductance,

- ω = 2πf is the angular frequency,

- f is the frequency and

- Lω = XL is the inductive reactance.

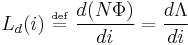

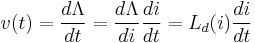

Nonlinear inductance

Many inductors make use of magnetic materials. These materials over a large enough range exhibit a nonlinear permeability with such effects as saturation. This in-turn makes the resulting inductance a function of the applied current. Faraday's Law still holds but inductance is ambiguous and is different whether you are calculating circuit parameters or magnetic fluxes.

The secant or large-signal inductance is used in flux calculations. It is defined as:

The differential or small-signal inductance, on the other hand, is used in calculating voltage. It is defined as:

The circuit voltage for a nonlinear inductor is obtained via the differential inductance as shown by Faraday's Law and the chain rule of calculus.

There are similar definitions for nonlinear mutual inductances.

See also

- Alternating current

- Dot convention

- Eddy current

- Electromagnetic induction

- Electricity

- Faraday's law of induction

- Gyrator

- Hydraulic analogy

- Inductor

- Leakage inductance

- LC circuit

- Magnetomotive force (MMF)

- RLC circuit

- RL circuit

- SI electromagnetism units

- Solenoid

- Transformer

- Kinetic inductance

References

- ↑ Heavyside, O. Electrician. Feb. 12, 1886, p. 271. See reprint

- ↑ "The Physics Hypertextbook: Inductance". 1998-2008. http://hypertextbook.com/physics/electricity/inductance/.

- ↑ Michael W. Davidson (1995-2008). "Molecular Expressions: Electricity and Magnetism Introduction: Inductance". http://micro.magnet.fsu.edu/electromag/electricity/inductance.html.

- ↑ Mahmood Nahvi, Joseph Edminister (2002). Schaum's outline of theory and problems of electric circuits. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 338. ISBN 0071393072. http://books.google.com/?id=nrxT9Qjguk8C&pg=PA338.

- ↑ Jackson, J. D. (1975). Classical Electrodynamics. Wiley. p. 262.

- ↑ Lorenz, L. (1879). "Über die Fortpflanzung der Elektrizität". Annalen der Physik VII: 161–193.

- ↑ Elliott, R. S. (1993). Electromagnetics. New York: IEEE Press. Note: The constant -3/2 in the result for a uniform current distribution is wrong.

General references

- Frederick W. Grover (1952). Inductance Calculations. Dover Publications, New York.

- Griffiths, David J. (1998). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-805326-X.

- Wangsness, Roald K. (1986). Electromagnetic Fields (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-81186-6.

- Hughes, Edward. (2002). Electrical & Electronic Technology (8th ed.). Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-582-40519-X.

- Küpfmüller K., Einführung in die theoretische Elektrotechnik, Springer-Verlag, 1959.

- Heaviside O., Electrical Papers. Vol.1. – L.; N.Y.: Macmillan, 1892, p. 429-560.

for w << 1

for w << 1 for w >> 1

for w >> 1