Scythians

The Scythians or Scyths[1] (Greek: Σκύθης, Σκύθοι) were an ancient Iranian people of horse-riding nomadic pastoralists[2][3] who throughout Classical Antiquity dominated the Pontic-Caspian steppe, known at the time as Scythia. By Late Antiquity the closely-related Sarmatians came to dominate the Scythians in this area. Much of the surviving information about the Scythians comes from the Greek historian Herodotus (c. 440 BC) in his Histories and Ovid in his poem of exile Epistulae ex Ponto, and archaeologically from the exquisite goldwork found in Scythian burial mounds in Ukraine and Southern Russia.

The name "Scythian" has also been used to refer to various peoples seen as similar to the Scythians, or who lived anywhere in a vast area covering present-day Central Asia, Russia, and Ukraine—known until medieval times as Scythia.[4] For example, the name of the Scythians has been used in reference to the Goths.[5]

Contents |

Etymology

The Histories of Herodotus provide the most important literary sources relating to ancient Scyths. According to Sulimirski,[6] Herodotus provides a broadly correct depiction but apparently knew little of the eastern part of Scythia. According to Herodotus the ancient Persians called all the Scyths "Saca" (Herodotus 7.64). Their principal tribe, the Royal Scyths, ruled the vast lands occupied by the nation as a whole (Herodotus 4.20); and they called themselves Skolotoi. Oswald Szemerényi devotes a thorough discussion to the etymology of the word Scyth in his work "Four old Iranian ethnic names: Scythian - Skudra - Sogdian - Saka".[7] The related words derive from *skeud, an ancient Indo-European word for archer (cf. English shoot), hence Assyrian Ishkuzi and Greek Skuth, represent Iranian *skuda (archer), which in turn in Scythian was rendered as Skula, (plural; skulata).

History and archeology

Origins and pre-history (to 700 BC)

Scholars generally classify the Scythian language as a member of the Eastern Iranian languages. The Scythians are thought to have originated from the Central Asian region of Greater Iran (Persia),[8][9][10][11][12] as a branch of the ancient Iranian peoples expanding north into the steppe regions from around 1000 BC.[7][6][13]

The Scythians first appeared in the historical record in the 8th century BC.[7] Herodotus reported three versions as to the origins of the Scythians, but placed greatest faith in this version:[14]

There is also another different story, now to be related, in which I am more inclined to put faith than in any other. It is that the wandering Scythians once dwelt in Asia, and there warred with the Massagetae, but with ill success; they therefore quitted their homes, crossed the Araxes, and entered the land of Cimmeria.

Around 676 BC, the Scythians (led by Ishpaki — Old Iranian *Spakaaya) in alliance with the Mannaens attacked Assyria. The group first appears in Assyrian annals under the name Ishkuzai. According to the brief assertion of Esarhaddon's inscription, the Assyrian empire defeated the alliance. Subsequent mention of Scythians in Babylonian and Assyrian texts occurs in connection with Media. Both Old Persian and Greek sources mention them during the period of the Achaemenid empires, with Greek sources locating them in the steppe between the Dnieper and Don rivers.

Josephus claimed that the Scythians were descended from Magog, the grandson of Noah.

Interpreting literary and archaeological evidence, contemporary scholars posit two major theories. The first major theory follows Herodotus' (third) account, stating that the Scythians were an Iranic group who arrived from Inner Asia. A second school of thought suggests a development autochthonous to the Pontic steppe/ trans-Caucasian region. They argue that the Scythians emerged from local groups of the Timber Grave culture (broadly associated with the "Cimmerians"), who rose as the new leaders of the region. This second theory is supported by anthropological evidence which found that Scythian skulls are similar to preceding findings from the Timber Grave culture, and distinct from those of the Central Asian Sacae.[15]

Classical Antiquity (600 BC to AD 300)

Herodotus provides the first detailed description of the Scythians. He classes the Cimmerians as a distinct autochthonous tribe, expelled by the Scythians from the northern Black Sea coast (Hist. 4.11–-12). Herodotus also states (4.6) that the Scythians consisted of the Auchatae, Catiaroi, Traspians and Paralatae or "Royal Scythians." Throughout his work Herodotus specifically distinguished between the nomadic Scythians in the south and the agricultural Scythians to the north.

For Herodotus, the Scythians were outlandish barbarians living north of the Black Sea in what are now Moldova and Ukraine—-Michael Kulikowski, Rome's Gothic wars

In 512 BC, when King Darius the Great of Persia attacked the Scythians, he allegedly penetrated into their land after crossing the Danube. Herodotus relates that the nomad Scythians succeeded in frustrating the designs of the Persian army by letting it march through the entire country without an engagement. According to Herodotus, Darius in this manner came as far as the Volga River.

During the 5th to 3rd centuries BC the Scythians evidently prospered. When Herodotus wrote his Histories in the 5th century BC, Greeks distinguished Scythia Minor in present-day Romania and Bulgaria from a Greater Scythia that extended eastwards for a 20-day ride from the Danube River, across the steppes of today's East Ukraine to the lower Don basin. The Don, then known as Tanaïs, has served as a major trading route ever since. The Scythians apparently obtained their wealth from their control over the slave-trade from the north to Greece through the Greek Black Sea colonial ports of Olbia, Chersonesos, Cimmerian Bosporus, and Gorgippia. They also grew grain, and shipped wheat, flocks, and cheese to Greece.

Strabo (c. 63 BC –- 24 AD) reports that King Ateas united under his power the Scythian tribes living between the Maeotian marshes and the Danube. His westward expansion brought him in conflict with Philip II of Macedon (reigned 359 to 336 BC), who took military action against the Scythians in 339 BC. Ateas died in battle, and his empire disintegrated. In the aftermath of this defeat, the Celts seem to have displaced the Scythians from the Balkans, while in south Russia a kindred tribe, the Sarmatians, gradually overwhelmed them. In 329 BC Philip's son, Alexander the Great, came into conflict with the Scythians at the Battle of Jaxartes. A nomad army sought to take revenge for the death of Ateas against the Macedonians, as they pushed the borders of their empire north and east, and take advantage of a revolt by the local Sogdian satrap. However, the nomad army was utterly crushed by Alexander, and following this defeat, the Scythians were no longer in a position to challenge the power of Macedon.

By the time of Strabo's account (the first decades of the first millennium AD), the Crimean Scythians had created a new kingdom extending from the lower Dnieper to the Crimea. The kings Skilurus and Palakus waged wars with Mithridates the Great (reigned 120–63 BC) for control of the Crimean littoral, including Chersonesos and the Cimmerian Bosporus. Their capital city, Scythian Neapolis, stood on the outskirts of modern Simferopol. The Goths destroyed it later, in the mid-3rd century AD.

Before the 20th century, some scholars assumed that the Scythians descended from the Mongolic people.[17] The Scythian community inhabited western Mongolia in the 5th and 6th centuries. The mummy of a Scythian warrior, which is believed to be about 2,500 years old, was a 30-to-40 year-old man with blond hair, and was found in the Altai, Mongolia.[18]

Sakas

Asians, especially Persians, knew the Scythians in Asia as Sakas. The Indo-Scythians had the name "Shaka" in South Asia, an extension on the name "Saka". Herodotus (7.64) describes them as Scythians, called by a different name:

The Sacae, or Scyths, were clad in trousers, and had on their heads tall stiff caps rising to a point. They bore the bow of their country and the dagger; besides which they carried the battle-axe, or sagaris. They were in truth Amyrgian (Western) Scythians, but the Persians called them Sacae, since that is the name which they gave to all Scythians.

In the Mahabharata, Sakas, Pahlavas, and Kambojas are mentioned as related tribes.

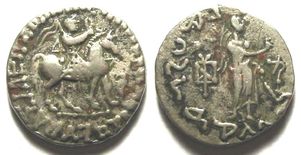

Indo-Scythians

In the 2nd century BC, a group of Scythian tribes, known as the Indo-Scythians, migrated into Bactria, Sogdiana and Arachosia. The migrations in 175–-125 BC of the Kushan (Chinese: "Yuezhi") tribes, who originally lived in eastern Tarim Basin before the Huns (Chinese: "Xiongnu") tribes dislodged them, displaced the Indo-Scythians from Central Asia. Led by their king Maues, they ultimately settled in modern-day Punjab and Kashmir from around 85 BC, where they replaced the kingdom of the Indo-Greeks by the time of Azes II (reigned c. 35–-12 BC). Kushans invaded again in the 1st century, but the Indo-Scythian rule persisted in some areas of Central India until the 5th century.

Hellenic-Scythian contact still focused on the Hellenistic cities and settlements of the Crimea (especially in the Bosporan Kingdom). Greek craftsmen from the colonies north of the Black Sea made spectacular Scythian-style gold ornaments (see below), applying Greek realism to depict Scythian motifs of lions, antlered reindeer, and gryphons.

Late Antiquity (AD 300 to 600)

In Late Antiquity the notion of a Scythian ethnicity grew more vague, and outsiders might dub any people inhabiting the Pontic-Caspian steppe as "Scythians", regardless of their language. Thus, Priscus, a Byzantine emissary to Attila, repeatedly referred to the latter's followers as "Scythians". But Eunapius, Claudius Cladianus and Olympiodorus usually mean "Goths" when they write "Scythians".

The Goths had displaced the Sarmatians in the 2nd century from most areas near the Roman frontier, and by early medieval times, the Turkic migration marginalized East Iranian dialects, and assimilated the Saka linguistically.

Archaeology

Archaeological remains of the Scythians include kurgan tombs (ranging from simple exemplars to elaborate "Royal kurgans" containing the "Scythian triad" of weapons, horse-harness, and Scythian-style wild-animal art), gold, silk, and animal sacrifices, in places also with suspected human sacrifices[19][20] Mummification techniques and permafrost have aided in the relative preservation of some remains. Scythian archaeology also examines the remains of North Pontic Scythian cities and fortifications[21]

The spectacular Scythian grave-goods from Arzhan, and others in Tuva have been dated from about 900 BC onward. One grave find on the lower Volga gave a similar date, and one of the Steblev graves from the eastern, European end of the Scythian area was dated to the late 8th century BC.[22]

Archaeologists can distinguish three periods of ancient Scythian archaeological remains:

- 1st period - pre-Scythian and initial Scythian epoch: from the 9th to the middle of the 7th century BC

- 2nd period - early Scythian epoch: from the 7th to the 6th century BC

- 3rd period - classical Scythian epoch: from the 5th to the 4th century BC

From the 8th century BC to the 2nd century BC, archaeology records a split into two distinct settlement areas: the older in the Sayan-Altai area in Central Asia, and the younger in the North Pontic area in Eastern Europe.[23]

Kurgans

Large burial mounds (some over 20 metres high), provide the most valuable archaeological remains associated with the Scythians. They dot the Ukrainian and south Russian steppes, extending in great chains for many kilometers along ridges and watersheds. From them archaeologists have learned much about Scythian life and art.[24] The Ukrainian term for such a burial mound, "kurhan" (Ukrainian: Курган) as well as the Russian term kurgan, derives from a Turkic word for "castle".[25]

Some Scythian-Sarmatian cultures may have given rise to the myth of Amazons. Graves of armed females have been found in southern Ukraine and Russia. David Anthony notes, "About 20% of Scythian-Sarmatian "warrior graves" on the lower Don and lower Volga contained females dressed for battle as if they were men, a phenomenon that probably inspired the Greek tales about the Amazons."[26]

Tamgas

Scythian tribes and clans have left behind them as important ethnological markers their tamgas (brand-marks which identify individual possession), a must for pastoral societies with shared grazing-ranges. Tamgas allow reconstruction of movements and family links where no written records have survived.

Besides identifying property, tamgas marked participation of members of the clan in collective actions (treaties, religious ceremonies, fraternization, public functions), and served as symbols of authority for minting coins. The tamga forms stayed unchanged for about 2,000 years within kindred ethnic groups, but after the decline of some famous clan another clan would adopt its tamga.

Wide use of tamgas originated from western Turkestan and Mongolia no later than the beginning of the 6th century BC. Analysis of tamgas for most powerful clans and for the kings of the Bosporus has allowed scholars to define precisely their genealogy and their relations with territories from where their forefathers migrated to Europe: Chorasm, Kang-Kü, Bactria, Sogdiana.[27]

Pazyryk culture

Some of the first Bronze Age Scythian burials documented by modern archaeologists include the kurgans at Pazyryk in the Ulagan district of the Altai Republic, south of Novosibirsk in the Altai Mountains of southern Siberia. Archaeologists have extrapolated the Pazyryk culture from these finds: five large burial mounds and several smaller ones between 1925 and 1949, one opened in 1947 by Russian archaeologist Sergei Rudenko. The burial mounds concealed chambers of larch-logs covered over with large cairns of boulders and stones.

Pazyryk culture flourished between the 7th and 3rd century BC in the area associated with the Sacae.

Ordinary Pazyryk graves contain only common utensils, but in one, among other treasures, archaeologists found the famous Pazyryk Carpet, the oldest surviving wool-pile oriental rug. Another striking find, a 3-metre-high four-wheel funerary chariot, survived superbly preserved from the 5th century BC.

Although some scholars sought to connect the Pazyryk nomads with indigenous ethnic groups of the Altai, Rudenko summed up the cultural context in the following dictum:

All that is known to us at the present time about the culture of the population of the High Altai, who have left behind them the large cairns, permits us to refer them to the Scythian period, and the Pazyryk group in particular to the fifth century BC. This is supported by radiocarbon dating.

Belsk excavations

Recent digs(see:Gelonus) in Belsk near Poltava (Ukraine) have uncovered a "vast city", with the largest area of any city in the world at that time. It has been tentatively identified by a team of archaeologists led by Boris Shramko as the site of Gelonus, the purported capital of Scythia. The city's commanding ramparts and vast area of 40 square kilometers exceed even the outlandish size reported by Herodotus. Its location at the northern edge of the Ukrainian steppe would have allowed strategic control of the north-south trade-route. Judging by the finds dated to the 5th and 4th centuries BC, craft workshops and Greek pottery abounded.

Tillia tepe treasure

A site found in 1968 in Tillia tepe (literally "The golden hill") in northern Afghanistan (former Bactria) near Shebergan consisted of the graves of five women and one man with extremely rich jewelry, dated to around the 1st century BC, and generally thought to belong to Scythian tribes. Altogether the graves yielded several thousands of pieces of fine jewelry, usually made from combinations of gold, turquoise and lapis-lazuli.

A high degree of cultural syncretism pervades the findings, however. Hellenistic cultural and artistic influences appear in many of the forms and human depictions (from amorini to rings with the depiction of Athena and her name inscribed in Greek), attributable to the existence of the Seleucid empire and Greco-Bactrian kingdom in the same area until around 140 BC, and the continued existence of the Indo-Greek kingdom in the northwestern Indian sub-continent until the beginning of our era. This testifies to the richness of cultural influences in the area of Bactria at that time.

Interesting fact is that in Bulgarian language the verb 'да се скитам / da se skitam' (to wander, move or travel slowly through or over) Cognitive скит- / skit- and the word скитник, скиталец/skitnik, skitalec have meaning of (wanderer, nomad).

Influence

China

Ancient influences from Central Asia became identifiable in China following contacts of metropolitan China with nomadic western and northwestern border territories from the 8th century BC. The Chinese adopted the Scythian-style animal art of the steppes (descriptions of animals locked in combat), particularly the rectangular belt-plaques made of gold or bronze, and created their own versions in jade and steatite.[28]

Following their expulsion by the Yuezhi, some Scythians may also have migrated to the area of Yunnan in southern China. Scythian warriors could also have served as mercenaries for the various kingdoms of ancient China. Excavations of the prehistoric art of the Dian civilization of Yunnan have revealed hunting scenes of Caucasoid horsemen in Central Asian clothing.[29]

Northeastern Asia

Scythian influences have been identified as far as Korea and Japan. Various Korean artifacts, such as the royal crowns of the kingdom of Silla, are said to be of Scythian design.[30] Similar crowns, brought through contacts with the continent, can also be found in Kofun era Japan.

Language

The Scythian language and its various dialects formed part of the Indo-European language-family. The personal names found in the contemporary Greek literary and epigraphic texts suggest that the language of the Scythians and the Sarmatians (who spoke a dialect of Scythian according to Hist. 4.117 Herodotus) belonged to the Northeast Iranian branch. An alternative theory suggests that at least some Scythian tribes, such as the Meotians (Sindi), spoke Indo-Aryan dialects.[31]

Naming and etymology

The Scythians known to Herodotus (Hist. 4.6) called themselves Skolotoi. The Greek word Skythēs probably reflects an older rendering of the very same name, *Skuδa- (whereas Herodotus transcribes the unfamiliar [ð] sound with Λ; -toi represents the North-east Iranian plural ending -ta). The word originally means "shooter, archer", and it ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European root *skeud- "to shoot, throw" (compare English shoot, German Schütze).

The Sogdians' name for themselves, Swγδ, may represent a related word (*Skuδa > *Suγuδa with an anaptyctic vowel). The name also occurs in Assyrian in the form Aškuzai or Iškuzai ("Scythian"). It may have provided the source for biblical Hebrew Ashkenaz (original *אשכוז ’škuz got misspelled as אשכנז ’šknz), later a Jewish name of the Germanic areas of Central Europe and hence a self-descriptor of the Central European Jews who lived there among the Ashkenazim ("Germans") at that time called Teutons or Wendels.

The Old Persians used another name for the Scythians, namely Saka, which perhaps derived from the Iranian verbal root sak- "to go, to roam", i.e. "wanderer, nomad". The Chinese knew the Saka (Asian Scythians) as Sai (Chinese character: 塞, Old Sinitic *sək). The modern Iranian province of Sistan takes its name from the classical Sakestan (place of Saka).[32][33][34]

Society

Scythians lived in confederated tribes, a political form of voluntary association which regulated pastures and organized a common defence against encroaching neighbors for the pastoral tribes of mostly equestrian herdsmen. While the productivity of domesticated animal-breeding greatly exceeded that of the settled agricultural societies, the pastoral economy also needed supplemental agricultural produce, and stable nomadic confederations developed either symbiotic or forced alliances with sedentary peoples — in exchange for animal produce and military protection.

Herodotus relates that three main tribes of the Scythians descended from three brothers, Lipoxais, Arpoxais, and Colaxais:[35]

In their reign a plough, a yoke, an axe, and a bowl, all made of gold, fell from heaven upon the Scythian territory. The oldest of the brothers wished to take them away, but as he drew near the gold began to burn. The second brother approached them, but with the like result. The third and youngest then approached, upon which the fire went out, and he was enabled to carry away the golden gifts. The two eldest then made the youngest king, and henceforth the golden gifts were watched by the king with the greatest care, and annually approached with magnificent sacrifices.[36]

Herodotus also mentions a royal tribe or clan, an elite which dominated the other Scythians:

Then on the other side of the Gerros we have those parts which are called the "Royal" lands and those Scythians who are the bravest and most numerous and who esteem the other Scythians their slaves.[37]

The elder brothers then, acknowledging the significance of this thing, delivered the whole of the kingly power to the youngest. From Lixopais, they say, are descended those Scythians who are called the race of the Auchatai; from the middle brother Arpoxais those who are called Catiaroi and Traspians, and from the youngest of them the "Royal" tribe, who are called Paralatai: and the whole together are called, they say, Scolotoi, after the name of their king; but the Hellenes gave them the name of Scythians. Thus the Scythians say they were produced; and from the time of their origin, that is to say from the first king Targitaos, to the passing over of Dareios [the Persian Emperor Darius I] against them [512 BC], they say that there is a period of a thousand years and no more.[38]

This royal clan is also named in other classical sources the "Royal Dahae". The rich burials of Scythian kings in (kurgans) is independent evidence for the existence of this powerful royal elite.

Although scholars have traditionally treated the three tribes as geographically distinct, Georges Dumézil interpreted the divine gifts as the symbols of social occupations, illustrating his trifunctional vision of early Indo-European societies: the plough and yoke symbolised the farmers, the axe — the warriors, the bowl — the priests.[39] According to Dumézil, "the fruitless attempts of Arpoxais and Lipoxais, in contrast to the success of Colaxais, may explain why the highest strata was not that of farmers or magicians, but rather that of warriors."[40]

Ruled by small numbers of closely-allied élites, Scythians had a reputation for their archers, and many gained employment as mercenaries. Scythian élites had kurgan tombs: high barrows heaped over chamber-tombs of larch-wood — a deciduous conifer that may have had special significance as a tree of life-renewal, for it stands bare in winter. Burials at Pazyryk in the Altay Mountains have included some spectacularly preserved Scythians of the "Pazyryk culture" — including the Ice Maiden of the 5th century BC.

Scythian women dressed in much the same fashion as men. A Pazyryk burial found in the 1990s contained the skeletons of a man and a woman, each with weapons, arrowheads, and an axe.

As far as we know, the Scythians had no writing system. Until recent archaeological developments, most of our information about them came from the Greeks. The Ziwiye hoard, a treasure of gold and silver metalwork and ivory found near the town of Sakiz south of Lake Urmia and dated to between 680 and 625 BC, includes objects with Scythian "animal style" features. One silver dish from this find bears some inscriptions, as yet undeciphered and so possibly representing a form of Scythian writing.

Homer called the Scythians "the mare-milkers". Herodotus described them in detail: their costume consisted of padded and quilted leather trousers tucked into boots, and open tunics. They rode with no stirrups or saddles, just saddle-cloths. Herodotus reports that Scythians used cannabis, both to weave their clothing and to cleanse themselves in its smoke (Hist. 4.73-75); archaeology has confirmed the use of cannabis in funeral rituals. The Scythian philosopher Anacharsis visited Athens in the 6th century BC and became a legendary sage.

Scythians also had a reputation for the use of barbed and poisoned arrows of several types, for a nomadic life centered on horses — "fed from horse-blood" according to Herodotus — and for skill in guerrilla warfare.The Scythians gold was made by dipping and pegging a sheep skin in a river that had gold and then it was lifted out and the skin was burnt leaving the gold to run out.

Amazons

The name may be derived from the Greek a-mazos or "without a breast", due to the legend that these female warriors cut off their right breasts so as to be better able to shoot with a bow and arrow. Another possibility is that Amazōn is the Ionian Greek form of the Iranian word ha-mazan, fighting together. The regular Greek form would be hamazōn, but because the Ionians dropped their "H's", hamazōn becomes amazōn, the form taken into the other Greek dialects [41].

Art

Scythian contacts with craftsmen in Greek colonies along the northern shores of the Black Sea resulted in the famous Scythian gold adornments that feature among the most glamorous artifacts of world museums. Ethnographically extremely useful as well, the gold depicts Scythian men as bearded, long-haired Caucasoids. "Greco-Scythian" works depicting Scythians within a much more Hellenic style date from a later period, when Scythians had already adopted elements of Greek culture.

Scythians had a taste for elaborate personal jewelry, weapon-ornaments and horse-trappings. They executed Central-Asian animal motifs with Greek realism: winged gryphons attacking horses, battling stags, deer, and eagles, combined with everyday motifs like milking ewes.

In 2000, the touring exhibition 'Scythian Gold' introduced the North American public to the objects made for Scythian nomads by Greek craftsmen north of the Black Sea, and buried with their Scythian owners under burial mounds on the flat plains of present-day Ukraine, most of them unearthed after 1980.

In 2001, the discovery of an undisturbed royal Scythian burial-barrow illustrated for the first time Scythian animal-style gold that lacks the direct influence of Greek styles. Forty-four pounds of gold weighed down the royal couple in this burial, discovered near Kyzyl, capital of the Siberian republic of Tuva.

Religion

The religious beliefs of the Scythians was a type of Pre-Zoroastrian Iranian religion and differed from the post-Zoroastrian Iranian thoughts.[42] Foremost in the Scythian pantheon stood Tabiti, who was later replaced by Atar, the fire-pantheon of Iranian tribes, and Agni, the fire deity of Indo-Aryans.[42] The Scythian belief was a more archaic stage than the Zoroastrian and Hindu systems. The use of cannabis to induce trance and divination by soothsayers was a characteristic of the Scythian belief system.[42]

Culture

Clothing

Men and women dressed differently. Herodotus mentioned that Sakas had " high caps and ...wore trousers." Clothing was sewn from plain-weave wool, hemp cloth, silk fabrics, felt, leather and hides. Pazyryk findings give the most number of almost fully preserved garments and clothing worn by the Scythian/Saka peoples. Ancient Persian bas-relief - Apadana or Behistun inscription, ancient Greek pottery, archaeological findings from Ukraine, Russia, Kazakhstan, China et al. give visual representations of these garments.

Headgear

Herodotus says Sakas had " high caps tapering to a point and stiffly upright." Asian Saka headgear is clearly visible on the Persepolis Apadana staircase bas-relief - high pointed hat with flaps over ears and the nape of the neck. From China to Danube delta men seemed to have worn a variety of soft headgear - either conical like the one described by Herodotus, or rounder, more like a Phrygian cap etc. Women wore a variety of different headdresses, some conical in shape others more like flattened cylinders, also adorned with metal (golden) plaques. Based on the Pazyryk findings (can be seen also in the south Siberian, Uralic and Kazakhstan rock drawings) some caps were topped with zoomorphic wooden sculptures firmly attached to a cap and forming an integral part of the headgear, similar to the surviving nomad helmets from northern China.

Tunics

Men and warrior women wore tunics, often embroidered, adorned with felt applique work, or metal (golden) plaques. Persepolis Apadana again serves a good starting point to observe tunics of the Sakas. They appear to be a sewn, long sleeve garment that extended to the knees and belted with a belt while owner's weapons were fastened to the belt (sword or dagger, gorytos, battleax, whetstone etc.). Based on numerous archeological findings in Ukraine, southern Russian and Kazakhstan men and warrior women wore long sleeve tunics that were always belted, often with richly ornamented belts. The Kazakhstan Saka (e.g. Issyk Golden Man/Maiden) wore shorter tunics and more close fitting tunics than the Pontic steppe Scythians. Some Pazyryk culture Saka wore short belted tunic with a lapel on a right side, upright collar, 'puffed' sleeves narrowing at a wrist and bound in narrow cuffs of a color different from the rest of the tunic.

Robes

Scythian women wore long, loose robes, ornamented with metal plaques (gold).

Shawls

Women wore shawls, often richly decorated with metal (golden) plaques.

Coats and cloaks

Men and women wore coats, e.g. Pazyryk Saka had many varieties, from fur to felt. They could have worn a ridding coat that later was known as a Median robe or Kantus. Long sleeved, and open, it seems that on the Persepolis Apadana Skudrian delegation is perhaps shown wearing such coat. Pazyryk felt tapestry shows a rider wearing a billowing cloak.

Trousers

Men and wore long trousers, often adorned with metal plaques and often embroidered or adorned with felt appliques; trousers could have been wider or tight fitting depending on the area. Materials used depended on the wealth, climate and necessity.

Footwear

Men and warrior women wore variations of long and shorter boots, wool-leather-felt gaiter-boots and moccasin-like shoes. They were either of a laced or simple slip on type. Women wore also soft shoes with metal (gold) plaques.

Belts

Men and women wore belts. Warrior belts were made of leather, often with gold or other metal adornments and had many attached leather thongs for fastening of the owner's gorytos, sword, whet stone, whip etc. Belts were fastened with metal or horn belt-hooks, leather thongs and metal (often golden) or horn belt-plates.

Historiography

Herodotus

Herodotus wrote about an enormous city, Gelonus, in the northern part of Scythia[43]

The Budini are a large and powerful nation: they have all deep blue eyes, and bright red hair. There is a city in their territory, called Gelonus, which is surrounded with a lofty wall, thirty furlongs [Polytonic

Herodotus and other classical historians listed quite a number of tribes who lived near the Scythians, and presumably shared the same general milieu and nomadic steppe culture, often called "Scythian culture", even though scholars may have difficulties in determining their exact relationship to the "linguistic Scythians". A partial list of these tribes includes the Agathyrsi, Geloni, Budini, and Neuri.

Herodotus presented four different versions of Scythian origins:

- Firstly (4.7), the Scythians' legend about themselves, which portrays the first Scythian king, Targitaus, as the child of the sky-god and of a daughter of the Dnieper. Targitaus allegedly lived a thousand years before the failed Persian invasion of Scythia, or around 1500 BC. He had three sons, before whom fell from the sky a set of four golden implements — a plough, a yoke, a cup and a battle-axe. Only the youngest son succeeded in touching the golden implements without them bursting with fire, and this son's descendants, called by Herodotus the "Royal Scythians", continued to guard them.

- Secondly (4.8), a legend told by the Pontic Greeks featuring Scythes, the first king of the Scythians, as a child of Hercules and Echidna.

- Thirdly (4.11), in the version which Herodotus said he believed most, the Scythians came from a more southern part of Central Asia, until a war with the Massagetae (a powerful tribe of steppe nomads who lived just northeast of Persia) forced them westward.

- Finally (4.13), a legend which Herodotus attributed to the Greek bard Aristeas, who claimed to have got himself into such a Bachanalian fury that he ran all the way northeast across Scythia and further. According to this, the Scythians originally lived south of the Rhipaean mountains, until they got into a conflict with a tribe called the Issedones, pressed in their turn by the Cyclopes; and so the Scythians decided to migrate westwards.

Persians and other peoples in Asia referred to the Scythians living in Asia as Sakas. Herodotus (IV.64) describes them as Scythians, although they figure under a different name:

The Sacae, or Scyths, were clad in trousers, and had on their heads tall stiff caps rising to a point. They bore the bow of their country and the dagger; besides which they carried the battle-axe, or sagaris. They were in truth Amyrgian (Western) Scythians, but the Persians called them Sacae, since that is the name which they gave to all Scythians.

Strabo

In the 1st century BC, the Greek-Roman geographer Strabo gave an extensive description of the eastern Scythians, whom he located in north-eastern Asia beyond Bactria and Sogdiana:[44]

Strabo went on to list the names of the various tribes among the Scythians, probably making an amalgam with some of the tribes of eastern Central Asia (such as the Tocharians):[44]

Now the greater part of the Scythians, beginning at the Caspian Sea, are called Daheans, but those who are situated more to the east than these are named Massageteans and Saceans, whereas all the rest are given the general name of Scythians, though each people is given a separate name of its own. They are all for the most part nomads. But the best known of the nomads are those who took away Bactriana from the Greeks (i.e. Greco-Bactrians), I mean the Asians, Pasians, Tocharians, and Sacarauls, who originally came from the country on the other side of the Jaxartes River that adjoins that of the Sacae and the Sogdians and was occupied by the Sacae. And as for the Daëans, some of them are called Aparns, some Xanthians, and some Pissures. Now of these the Aparni are situated closest to Hyrcania and the part of the sea that borders on it, but the remainder extend even as far as the country that stretches parallel to Aria.

Indian sources

Sakas receive numerous mentions in Indian texts, including the Puranas, the Manusmriti, the Ramayana, the Mahabharata, the Mahabhashya of Patanjali, the Brhat Samhita of Varaha Mihira, the Kavyamimamsa, the Brhat-Katha-Manjari and the Kaṭha–Saritsagara.

Genetics

Mitochondrial DNA extracted from skeletal remains obtained from excavated Scythian kurgans have produced a myriad of results and conclusions. Analysis of the HV1 sequence obtained from a male Scytho-Siberian's remains at the Kizil site in the Altai Republic revealed the individual possessed the N1a maternal lineage. The study also noted that haplogroup mtDNA N1a was found at a relatively high frequency in the southern fringes of the Eurasian steppe, Iran (8.3%), and within the Indian Havik group (8.3%), an upper Brahmin caste. From this, a possible link to ancient populations presumed to have come from Europe that lived in the neighboring Central Asian parts of India and Iran was suggested.[45]

Additionally, mitochondrial DNA has been extracted from two Scytho-Siberian skeletons found in the Altai Republic (Russia) dating back 2,500 years. Both remains were determined to be of males from a population who had characteristics "of mixed Euro-Mongoloid origin". However it should be noted that "European individual ancestry" does not necessarily mean that these individuals were from Europe, as no test to distinguish between European and Asian Caucasoids was performed[46]. One of the individuals was found to carry the F2a maternal lineage, and the other the D lineage, both of which are characteristic of East Eurasian populations.[47]

Maternal genetic analysis of Saka period male and female skeletal remains from a double inhumation kurgan located at the Beral site in Kazakhstan determined that the two were most likely not closely related and were possibly husband and wife. The HV1 mitochondrial sequence of the male was similar to the Anderson sequence which is most frequent in European populations. Contrary, the HV1 sequence of the female suggested a greater likelihood of Asian origins. The study's findings were in line with the hypothesis that mixings between Scythians and other populations occurred. This was buttressed by the discovery of several objects with a Chinese inspiration in the grave. No conclusive associations with haplogroups were made though it was suggested that the female may have derived from either mtDNA X or D.[48]

Y-Chromosome DNA testing performed on ancient Scythian skeletons dating to the Bronze and Iron Ages in the Krasnoyarsk region found that all but one of 11 subjects carried Y-DNA R1a1, with blue or green eye color and light hair common, suggesting mostly European origin of that particular population.[49] Additional testing on the Xiongnu specimens revealed that the Scytho-Siberian skeleton (dated to the 5th century BCE) from the Sebÿstei site exhibited R1a1 haplogroup. Moreoever, the STR haplotype motifs characterising these R1a1 haplogroups were found to closely resemble those found amongst current Balto-Slavic populations in eastern Europe, as well as in indigenous populations in southern Siberia. In contrast, they were found only sporadically amongst central and east Asian populations, and not at all amongst western Europeans[49].

Post-classical "Scythians"

Migration period

Although the classical Scythians may have largely disappeared by the 1st century BC, Eastern Romans continued to speak conventionally of "Scythians" to designate Germanic tribes and confederations[50] or mounted Eurasian nomadic barbarians in general: in 448 AD two mounted "Scythians" led the emissary Priscus to Attila's encampment in Pannonia. The Byzantines in this case carefully distinguished the Scythians from the Goths and Huns who also followed Attila.

The Sarmatians (including the Alans and finally the Ossetians) counted as Scythians in the broadest sense of the word — as speakers of Northeast Iranian languages — but nevertheless remain distinct from the Scythians proper.[51]

Byzantine sources also refer to the Rus raiders who attacked Constantinople around 860 AD in contemporary accounts as "Tauroscythians", because of their geographical origin, and despite their lack of any ethnic relation to Scythians. Patriarch Photius may have first applied the term to them during the Siege of Constantinople (860).

Early Modern usage

Owing to their reputation as established by Greek historians, the Scythians long served as the epitome of savagery and barbarism in the early modern period. Shakespeare, for instance, alluded to the legend that Scythians ate their children in his play King Lear:

The barbarous Scythian

Or he that makes his generation messes

To gorge his appetite, shall to my bosom

¨ Be as well neighbour'd, pitied, and relieved,

As thou my sometime daughter.[52]

Characteristically, early modern English discourse on Ireland frequently resorted to comparisons with Scythians in order to confirm that the indigenous population of Ireland descended from these ancient "bogeymen", and showed themselves as barbaric as their alleged ancestors. Edmund Spenser wrote that

the Chiefest [nation that settled in Ireland] I Suppose to be Scithians ... which firste inhabitinge and afterwarde stretchinge themselves forthe into the lande as theire numbers increased named it all of themselues Scuttenlande which more brieflye is Called Scuttlande or Scotlande.[53]

As proofs for this origin Spenser cites the alleged Irish customs of blood-drinking, nomadic lifestyle, the wearing of mantles and certain haircuts and

Cryes allsoe vsed amongeste the Irishe which savor greatlye of the Scythyan Barbarisme.

William Camden, one of Spenser's main sources, comments on this legend of origin that

to derive descent from a Scythian stock, cannot be thought any waies dishonourable, seeing that the Scythians, as they are most ancient, so they have been the Conquerours of most Nations, themselves alwaies invincible, and never subject to the Empire of others.[54]

The 15th-century Polish chronicler Jan Długosz was the first to connect the prehistory of Poland with Sarmatians, and the connection was taken up by other historians and chroniclers, such as Marcin Bielski, Marcin Kromer and Maciej Miechowita. Other Europeans depended for their view of Polish Sarmatism on Miechowita's Tractatus de Duabus Sarmatiis, a work which provided a substantial source of information about the territories and peoples of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in a language of international currency.[55] Tradition specified that the Sarmatians themselves were descended from Japheth, son of Noah.[56]

In the 17th and 18th centuries, foreigners regarded the Russians as descendants of Scythians. It became conventional to refer to Russians as Scythians in 18th century poetry, and Alexander Blok drew on this tradition sarcastically in his last major poem, The Scythians (1920). In the nineteenth century, romantic revisionists in the West transformed the "barbarian" Scyths of literature into the wild and free, hardy and democratic ancestors of all blond Indo-Europeans.

Descent claims

A number of groups have claimed possible descent from the Scythians, including the Ossetians, Pashtuns, the Turkic Kazakhs and Yakuts (whose endoethnonym is "Sakha"), and Parthians (whose homelands laid to the east of the Caspian Sea and thought to have come there from north of the Caspian). Some legends of the Picts; the Gaels; the Hungarians; Serbs and Croats (among others) also include mention of Scythian origins. In the second paragraph of the 1320 Declaration of Arbroath the élite of Scotland claim Scythia as a former homeland of the Scots. Some writers claim that Scythians figured in the formation of the empire of the Medes and likewise of Caucasian Albania.

The Carolingian kings of the Franks traced Merovingian ancestry to the Germanic tribe of the Sicambri. Gregory of Tours documents in his History of the Franks that when Clovis was baptised, he was referred to as a Sicamber with the words "Mitis depone colla, Sicamber, adora quod incendisti, incendi quod adorasti."'. The Chronicle of Fredegar in turn reveals that the Franks believed the Sicambri to be a tribe of Scythian or Cimmerian descent, who had changed their name to Franks in honour of their chieftain Franco in 11 BC. The Scythians also feature in some post-Medieval national origin-legends of the Celts.

Based on such accounts of Scythian founders of certain Germanic as well as Celtic tribes, British historiography in the British Empire period such as Sharon Turner in his History of the Anglo-Saxons, made them the ancestors of the Anglo-Saxons. The idea was taken up in the British Israelism of John Wilson, who adopted and promoted the "idea that the "European 'race', in particular the Anglo-Saxons, were descended from certain Scythian tribes, and these Scythian tribes (as many had previously stated from the Middle Ages onward) were in turn descended from the ten Lost Tribes of Israel."[57] Tudor Parfitt, author of The Lost Tribes of Israel, points out that the proof cited by adherents of British Israelism is "of a feeble composition even by the low standards of the genre."[58]

Whatever the claims of various modern ethnic groups, the peoples once known as the Scythians of Antiquity were amalgamated into the various Slavic groups of eastern and southeastern Europe.[59]

See also

References

- ↑ Scythian is pronounced /ˈsɪθi.ən/ or /ˈsɪði.ən/. Scyth is pronounced /ˈsɪθ/. From Greek Σκύθης. Note Scytho- /ˈsaɪθoʊ/ in composition (OED).

- ↑ Scythian, member of a nomadic people originally of Iranian people who migrated from Central Asia to southern Russia in the 8th and 7th centuries BC—The New Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th edition—Micropædia on "Scythian", 10:576

- ↑ Scythian mummy shown in Germany, BBC News

- ↑ Frozen Siberian Mummies Reveal a Lost Civilization, Discover magazine

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski Rome's Gothic Wars, page 15. "And so the Goths, when they first appear in our written sources, are Scythians- they lived where the Scythians had once lived, they were the barbarian mirror image of the civilised Greek world as the Scytians had been, and so they were themselves Scytians."

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Sulimirski, T. "The Scyths" in: The Cambridge History of Iran; vol. 2: 149-99 Azargoshnasp.net

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Szemerényi, Oswald (1980) "Four old Iranian ethnic names: Scythian; Skudra; Sogdian; Saka" in: Sitzungsberichte der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften; 371 = Scripta minora, vol. 4, pp. 2051–93 Azagoshnasp.net

- ↑ Kuhrt, Amélie, ed. (2007) The Persian Empire: a Corpus of Sources of the Achaemenid Period; Volume 1; p. 44

- ↑ Farley, Frank Edgar (2009) Scandinavian Influences in the English Romantic Movement; p. 197

- ↑ Saklani, Dinesh Prasad (1998) Ancient Communities of the Himalaya; p. 42

- ↑ Bosworth, Joseph (1848) The Origin of the English, Germanic, and Scandinavian Languages, and Nations; p. 204

- ↑ MSN Encarta - Scythians, Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2009, Contributed By: Maria Brosius, D.Phil, 1997–2009, 2009-09-30

- ↑ Grousset, René (1989) "The empire of the Steppes". Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; p. 19. Jacobson, Esther. "The Art of Scythians", Brill Academic Publishers, 1995, pg 63 ISBN 90-04-09856-9 Gamkrelidze and Ivanov. Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Typological Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture (Parts I and II). Tbilisi State University., 1984 Mallory, J.P. . In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language Archeology and Myth. Thames and Hudson. Read Chapter 2 and see 51-53 for a quick reference.(1989) Newark, T. The Barbarians: Warriors and wars of the Dark Ages, Blandford: New York. See pages 65, 85, 87, 119-139. ,1985 Renfrew, C. Archeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European origins, Cambridge University Press, 1988 Abaev, V.I. and H. W. Bailey, "Alans", Encyclopædia Iranica, Vol. 1. pp. 801–803. ; Great Soviet Encyclopedia, (translation of the 3rd Russian-language edition), 31 vols., New York, 1973–1983. Vogelsang, W J The rise & organisation of the Achaemenid empire — the eastern evidence (Studies in the History of the Ancient Near East Vol. III). Leiden: Brill. pp. 344., 1992 ISBN 90-04-09682-5. Sinor, Denis. Inner Asia: History — Civilization — Languages, Routledge, 1997 pg 82 ISBN 0-7007-0896-0 ; "Scythian." (2006). In Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved September 7, 2006, from Encyclopædia Britannica Premium Service Masica, Colin P. The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge University Press, 1993, pg 48 ISBN 0-521-29944-6

- ↑ Herodotus 4.11 trans. G. Rawlinson.

- ↑ Pavel Dolukhanov. The Early Slavs. Eastern Europe from the initial Settlement to the Kievan Rus. Longman, 1996. Pg 125 (& references therin)

- ↑ Michael Kulikowski Rome's Gothic wars page 14

- ↑ The Mysterious Scythians Burst Into History

- ↑ Archeological Sensation-Ancient Mummy Found in Mongolia

- ↑ Hughes, Dennis. (1991) Human Sacrifice in Ancient Greece. Routledge pp. 10, 64-65, 118.

- ↑ Baldick, Julian. (2000) Animals and Shaman: Ancient Religions of Central Asia. I.B. Tauris. pp.35–36.

- ↑ Tsetskhladze, Gocha R. (2001) North Pontic Archaeology: Recent Discoveries and Studies. BRIL. pp. 5–474.

- ↑ Some problems in the study of the chronology of the Ancient Nomadic Cultures in Eurasia (9th - 3rd centuries BC. A. Yu. Alekseev, N. A. Bokovenko, Yu. Boltrik, et alia. Geochronometria Vol. 21, pp 143–150, 2002. Journal on Methods and Applications of Absolute Chronology.

- ↑ A. Yu. Alekseev et al., "Chronology of Eurasian Scythian Antiquities..."

- ↑ John Boardman, I. E. S. Edwards, E. Sollberger, N. G. L. Hammond. The Cambridge Ancient History. Cambridge University Press. January 16, 1992, pg 550.

- ↑ "kurgan." Merriam-Webster, 2002. Webster's Third New International Dictionary, Unabridged (10 October 2006).

- ↑ Anthony, David W. (2007). The Horse, the Wheel, and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691058873. http://books.google.com/books?id=rOG5VcYxhiEC.

- ↑ S. A. Yatsenko, Tamgas ...

- ↑ Mallory and Mair, The Tarim Mummies: Ancient China and the Mystery of the Earliest Peoples from the West, 2000)

- ↑ "Les Saces", Iaroslav Lebedynsky, p.73 ISBN 2877723372

- ↑ Crowns similar to the Scythian ones discovered in Tillia Tepe "appear later, during the 5th and 6th century at the eastern edge of the Asia continent, in the tumulus tombs of the Kingdom of Silla, in South-East Korea. "Afganistan, les trésors retrouvés", 2006, p282, ISBN 9782711852185

- ↑ Rjabchikov 2004

- ↑ Donna Rosenberg, "World Mythology: An Anthology of Great Myths and Epics ", NTC Pub. Group, 1999. pg 58. excerpt: "Later, in the second century B.C., related Saka tribes moved southwest from Sakestan ("the land of the Sakas") to the area that become Seistan and Zabulistan on the eastern border of Persia."

- ↑ B.N. Puri, "The Sakas and Indo-Parthians" in Ahmad Hasan Dani, Vadim Mikhaĭlovich Masson, János Harmatta, Boris Abramovich Litvinovskiĭ, Edmund Bosworth. History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Motilal Banarsidass Publ, 1999. excerpt:""The Indo-Greeks in Kabul impeded further Saka progress and compelled them to move westwards in the direction of Herat and thence to Sistan. This country was finally named Sakastan after them."

- ↑ Jane Hathaway, "A Tale of Two Factions: Myth, Memory, and Identity in Ottoman Egypt and Yemen". SUNY Press, 2003. excerpt:"Sistan (Sakastan) takes its name from the Scythians"

- ↑ Traces of the Iranian root xšaya — "ruler" — may persist in all three names.

- ↑ Herodotus. History. Book IV, verse 5. http://etext.library.adelaide.edu.au/h/herodotus/h4m/complete.html.

- ↑ Herodotus. History. Book IV, verses 19–20. http://etext.library.adelaide.edu.au/h/herodotus/h4m/complete.html.

- ↑ Herodotus. History. Book IV, verses 6–7. http://etext.library.adelaide.edu.au/h/herodotus/h4m/complete.html.

- ↑ The first scholar to compare the three strata of Scythian society to the Indian castes, Arthur Christensen, published Les types du premiere homme et du premier roi dans l'histoire legendaire des Iraniens, I (Stockholm, Leiden, 1917).

- ↑ Quoted in Wouter Wiggert Belier. Decayed Gods: Origin and Development of Georges Dumezil's "Ideologie Tripartie". Brill Academic Publishers, 1991. ISBN 90-04-06195-9. Page 69.

- ↑ Dictionary.com, Amazon

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 J.Harmatta: "Scythians" in UNESCO Collection of History of Humanity - Volume III: From the Seventh Century BC to the Seventh Century AD. Routledge/UNESCO. 1996. pg 182

- ↑ Herodotus 4.108 trans. Rawlinson.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Strabo, Geography, 11.8.1

- ↑ Ricaut, F. et al. 2004. Genetic Analysis of a Scytho-Siberian Skeleton and Its Implications for Ancient Central Asian Migrations. Human Biology. 76 (1): 109–125

- ↑ Bouakaze, 2009 :Pigment phenotype and biogeographical ancestry from ancient skeletal remains: inferences from multiplexed autosomal SNP analysis

- ↑ Ricaut,F. et al. 2004. Genetic Analysis and Ethnic Affinities From Two Scytho-Siberian Skeletons. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 123:351–360

- ↑ Clisson, I. et al. 2002. Genetic analysis of human remains from a double inhumation in a frozen kurgan in Kazakhstan (Berel site, Early 3rd Century BC). International Journal of Legal Medicine. 116:304–308

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Keyser, Christine (May 16, 2009). "Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people". Human Genetics. http://www.springerlink.com/content/4462755368m322k8/?p=087abdf3edf548a4a719290f7fc84a62&pi=0. Retrieved April 6, 2010.

- ↑ see Zosimus, Historia Nova, 1.23 & 1.28, also Zonaras, Epitome historiarum, book 12. Also the title "Scythika" of the lost work of the 3rd century Greek historian Dexippus who narrated the Germanic invasions of his age

- ↑ The Ossetes, the only Iranian people presently[update] resident in Europe, call their country Iriston or Iron, though North Ossetia now[update] officially has the designation Alania. They speak an North-Eastern Iranian language Ossetic, whose more widely-spoken dialect, Iron or Ironig (i.e. Iranian), preserves some similarities with the Gathic Avestan language, another Iranian language of the Eastern branch.

- ↑ King Lear Act I, Scene i.

- ↑ A View of the Present State of Ireland, c. 1596.

- ↑ Britannia, 1586 etc., English translation 1610.

- ↑ Andrzej Wasko, Sarmatism or the Enlightenment: The Dilemma of Polish Culture, Sarmatian Review XVII.2.

- ↑ Colin Kidd, British Identities before Nationalism; Ethnicity and Nationhood in the Atlantic World, 1600–1800, Cambridge University Press, 1999, p. 29

- ↑ Parfitt, Tudor (2003). The Lost Tribes of Israel: The History of a Myth. Phoenix. p. 54.

- ↑ Parfitt, Tudor (2003). The Lost Tribes of Israel: The History of a Myth. Phoenix. p. 61.

- ↑ The Myth of Nations. Patrick Geary. Page 145 the Slavs.. formed as they were through amalgams of what the Roman sources termed Scythian and Sarmatian and Germannic populations..

Further reading

|

Indo-European topics |

|---|

| Indo-European languages (list) |

| Albanian · Armenian · Baltic Celtic · Germanic · Greek Indo-Iranian (Indo-Aryan, Iranian) Italic · Slavic extinct: Anatolian · Paleo-Balkan (Dacian, |

| Proto-Indo-European language |

| Vocabulary · Phonology · Sound laws · Ablaut · Root · Noun · Verb |

| Indo-European language-speaking peoples |

| Europe: Balts · Slavs · Albanians · Italics · Celts · Germanic peoples · Greeks · Paleo-Balkans (Illyrians · Thracians · Dacians) ·

Asia: Anatolians (Hittites, Luwians) · Armenians · Indo-Iranians (Iranians · Indo-Aryans) · Tocharians |

| Proto-Indo-Europeans |

| Homeland · Society · Religion |

| Indo-European studies |

- Alekseev, A. Yu. et al., "Chronology of Eurasian Scythian Antiquities Born by New Archaeological and 14C Data". Radiocarbon, Vol .43, No 2B, 2001, p 1085–1107.

- Davis-Kimball, Jeannine. 2002. Warrior Women: An Archaeologist's Search for History's Hidden Heroines. Warner Books, New York. 1st Trade printing, 2003. ISBN 0-446-67983-6 (pbk).

- Gamkrelidze and Ivanov (1984). Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Typological Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture (Parts I and II). Tbilisi State University.

- Harmatta, J., "Studies in the History and Language of the Sarmatians", Acta Universitatis de Attila József Nominatae. Acta antique et archaeologica Tomus XIII. Szeged 1970, Kroraina.com

- (German) Jaedtke, Wolfgang. Steppenkind, Piper Verlag, Munich 2008. ISBN 978-3-492-25146-4. This novel contains detailed descriptions of the life of nomadic Scythians around 700 BC.

- Lebedynsky, I. (2001). "Les Scythes: la civilisation nomade des steppes VIIe - III siècle av. J.-C." / Errance, Paris.

- Lebedynsky Iaroslav (2006) "Les Saces", Editions Errance, ISBN 2877723372

- Mallory, J.P. (1989). In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language Archeology and Myth. Thames and Hudson. Chapter 2; and pages 51–53 for a quick reference.

- Newark, T. (1985). The Barbarians: Warriors and wars of the Dark Ages. Blandford: New York. See pages 65, 85, 87, 119-139.

- Renfrew, C. (1988). Archeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European origins. Cambridge University Press.

- Rolle, Renate, The world of the Scythians, London and New York (1989).

- (Russian) Rjabchikov, S. V., The Scythians, Sarmatians, Meotians and Slavs: Sign System, Mythology, Folklore. Rostov-on-Don, 2004

- (Russian) Rybakov, Boris. Paganism of Ancient Rus. Nauka, Moscow, 1987

- Sulimirski, T. "The Scyths", in Cambridge History of Iran, vol. 2: 149-99, Azargoshnasp.net

- Szemerényi, O., "Four Old Iranian Ethnic Names: Scythian - Skudra - Sogdian - Saka", Vienna (1980), Azargoshnasp.net

- Torday, Laszlo (1998). Mounted Archers: The Beginnings of Central Asian History. Durham Academic Press. ISBN 1-900838-03-6.

- (Russian) Yatsenko, S. A., "Tamgas of Iranolingual antique and Early Middle Ages people". Russian Academy of Science, Moscow Press "Eastern Literature", 2001

External links

- The Slavonic Antiquity by Sergei V. Rjabchikov

- "A chronology of the Scythian antiquities of Eurasia based on new archaeological and C-14 data", Alekseev, A.Y. et al. A detailed scholarly article on pre-Scythian, early Scythian and classical Scythian archaeological sites and their dating, by the Hermitage Museum's director of archaeology and others.

- "Some problems in the study of the chronology of the ancient nomadic cultures in Eurasia (9th - 3rd centuries BC)", Alekseev, A.Y. et al. More of the same.

- "Scythian Gold From Siberia Said to Predate the Greeks" A journalist's article on the Arzhan finds, quoting Hermitage experts

- A Scythian warrior found at a height of 2600 metres in the Altay Mountains in an intact burial mound (August 25, 2006)

- Scythians overview by Chris Bennet

- Livius website articles on ancient history, entry on Scythians/Sacae by Jona Lendering

- The early burial in Tuva

- Scythian myth and culture; map

- Color illustrations of Scythian gold

- Published excavations of royal Scythian kurgan (barrow) at Chertomlyk reviewed

- all known Scythian kings listed on Regnal Chronologies

- Herodotus, Histories, Book IV - translated by Rawlinson, the 1942 edition

- Livio Stecchini, "The Mapping of the Earth: Scythia": reconstructing the map of Scythia according to the conceptual geography of Herodotus

- Livio Stecchini, "The Mapping of the Earth: Gerrhos"

- 1998 NOVA documentary: "Ice Mummies: Siberian Ice Maiden" Transcript

- on Sarmatian (a related Iranian group) trade and ethnic connections

- Scythia Group (a Yahoo group for discussing the Scythians)

- Ryzhanovka

- Genetics

- Haplogroups in India (PDF file)

- Y-Chromosome Biallelic Haplogroups

- Unravelling migrations in the steppe: mitochondrial DNA sequences from ancient central Asians.

- Ancient DNA provides new insights into the history of south Siberian Kurgan people

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||