Scientology

| Scientology | |

|---|---|

The Scientology Symbol is composed of the letter S that stands for Scientology and the ARC and KRC triangles, two important concepts in Scientology |

|

| Formation | 1953 |

| Type | Religious / Commercial |

| Headquarters | Church of Scientology International, Los Angeles, California, USA |

| Chairman of Religious Technology Center | David Miscavige |

| Website | scientology.org |

Scientology is a body of beliefs and related practices created by L. Ron Hubbard (1911–1986), starting in 1952, as a successor to his earlier self-help system, Dianetics.[1] Hubbard characterized Scientology as a religion, and in 1953 incorporated the Church of Scientology in Camden, New Jersey.[2][3]

Scientology teaches that people are immortal spiritual beings who have forgotten their true nature.[4] Its method of spiritual rehabilitation is a type of counseling known as auditing, in which practitioners aim to consciously re-experience painful or traumatic events in their past in order to free themselves of their limiting effects.[5] Study materials and auditing courses are made available to members in return for specified donations.[6] Scientology is legally recognized as a tax-exempt religion in the United States and some other countries,[7][8][9][10] and the Church of Scientology emphasizes this as proof that it is a bona fide religion.[11] In other countries such as France, Germany and the United Kingdom, Scientology does not have comparable religious status.

A large number of organizations overseeing the application of Scientology have been established,[12] the most notable of these being the Church of Scientology. Scientology sponsors a variety of social service programs.[12][13] These include a set of moral guidelines expressed in a brochure called The Way to Happiness, the Narconon anti-drug program, the Criminon prison rehabilitation program, the Study Tech education methodology, a volunteer organization, and a business management method.[14]

Scientology has been surrounded by controversies since its inception. It has often been described as a cult that financially defrauds and abuses its members, charging exorbitant fees for its spiritual services.[6][15][16] The Church of Scientology has consistently used litigation against such critics, and its aggressiveness in pursuing its foes has been condemned as harassment.[17][18] Further controversy has focused on Scientology's belief that souls ("thetans") reincarnate and have lived on other planets before living on Earth.[19] Former members say that some of Hubbard's writings on this remote extraterrestrial past, included in confidential Upper Levels, are not revealed to practitioners until they have paid thousands of dollars to the Church of Scientology.[20][21] Another controversial belief held by Scientologists is that the practice of psychiatry is destructive and abusive and must be abolished.[22][23]

Contents |

Etymology and earlier usage

The word Scientology is a pairing of the Latin word scientia ("knowledge", "skill"), which comes from the verb scīre ("to know"), and the Greek λόγος lógos ("word" or "account [of]").[24][25]

In 1901, Allen Upward coined Scientology "as a disparaging term, to indicate a blind, unthinking acceptance of scientific doctrine" according to the Internet Sacred Text Archive as quoted in the preface to Forgotten Books' recent edition of Upward's book, The New Word: On the meaning of the word Idealist.[26] Continuing to quote, the publisher writes "I'm not aware of any evidence that Hubbard knew of this fairly obscure book."[27]

In 1934, philosopher A Nordenholz published a book that used the term to mean "science of science".[28] It is also uncertain whether Hubbard was aware of this prior usage of the word.[29]

History

Dianetics

Scientology was developed by L Ron Hubbard as a successor to his earlier self-help system, Dianetics. Dianetics uses a counseling technique known as auditing, developed by Hubbard to enable conscious recall of traumatic events in an individual's past.[5] It was originally intended to be a new psychotherapy and was not expected to become the foundation for a new religion.[31][32]

Hubbard, an American writer of pulp fiction, especially science fiction,[33] first published his ideas on the human mind in the Explorers Club Journal and the May 1950 issue of Astounding Science Fiction magazine.[34] Two of Hubbard's key supporters at the time were John W. Campbell Jr., the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, and Dr. Joseph A. Winter. Winter, hoping to have Dianetics accepted in the medical community, submitted papers outlining the principles and methodology of Dianetic therapy to the Journal of the American Medical Association and the American Journal of Psychiatry in 1949, but these were rejected.[35][36]

May 1950 saw the publication of Hubbard's Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health. His book entered the New York Times best-seller list in June 18 and stayed there until December 24 of that year.[37] Dianetics appealed to a broad range of people who used instructions from the book and applied the method to each other, becoming practitioners themselves.[34][38] Hubbard found himself the leader of a growing Dianetics movement.[34] He became a popular lecturer and established the Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation in Elizabeth, New Jersey, where he trained his first Dianetics counselors or auditors.[34][38]

Dianetics soon met with criticism. Morris Fishbein, the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association and well-known at the time as a debunker of quack medicine, dismissed Hubbard's book.[39] An article in Newsweek stated that "the dianetics concept is unscientific and unworthy of discussion or review".[40] In January 1951, the New Jersey Board of Medical Examiners instituted proceedings against the Hubbard Dianetic Research Foundation for teaching medicine without a license, which eventually led to that foundation's bankruptcy.[41][42][43]

Some practitioners of Dianetics reported experiences which they believed had occurred in past lives, or previous incarnations.[38] In early 1951, reincarnation became a subject of intense debate within Dianetics.[44] Campbell and Winter, who was still hopeful of winning support for Dianetics from the medical community, championed a resolution to ban the topic.[44] But Hubbard decided to take the reports of past life events seriously and postulated the existence of the thetan, a concept similar to the soul.[38] This was an important factor in the transition from secular Dianetics to the religion of Scientology.[38]

Also in 1951, Hubbard introduced the electropsychometer (E-meter for short) as an auditing aid.[44] Based on a design by Hubbard, the device is held by Scientologists to be a useful tool in detecting changes in a person's state of mind.[44]

The Church of Scientology

In 1952, Hubbard built on the existing framework set forth in Dianetics, and published a new set of teachings as Scientology, a religious philosophy.[45] In December 1953, Hubbard incorporated three churches – a "Church of American Science", a "Church of Scientology" and a "Church of Spiritual Engineering" – in Camden, New Jersey.[46] On 18 February 1954, with Hubbard's blessing, some of his followers set up the first local Church of Scientology, the Church of Scientology of California, adopting the "aims, purposes, principles and creed of the Church of American Science, as founded by L. Ron Hubbard."[46][47] The movement spread quickly through the United States and to other English-speaking countries such as Britain, Ireland, South Africa and Australia.[48] The second local Church of Scientology to be set up, after the one in California, was in Auckland, New Zealand.[48] In 1955, Hubbard established the Founding Church of Scientology in Washington, D.C.[38] In 1957, the Church of Scientology of California was granted tax-exempt status by the United States Internal Revenue Service (IRS), and so, for a time, were other local churches.[39][49] In 1958 however, the IRS started a review of the appropriateness of this status.[39] In 1959, Hubbard moved to England, remaining there until the mid-1960s.[38]

The Church experienced further challenges. The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) began an investigation concerning the claims the Church of Scientology made in connection with its E-meters.[39] On January 4, 1963, they raided offices of the Church of Scientology and seized hundreds of E-meters as illegal medical devices. The devices have since been required to carry a disclaimer saying that they are a purely religious artifact.[50]

In the mid-sixties, the Church of Scientology was banned in several Australian states, starting with Victoria in 1965.[51] The ban was based on the Anderson Report, which found that the auditing process involved "command" hypnosis, in which the hypnotist assumes "positive authoritative control" over the patient. On this point the report stated,

It is the firm conclusion of this Board that most scientology and dianetic techniques are those of authoritative hypnosis and as such are dangerous ... the scientific evidence which the Board heard from several expert witnesses of the highest repute ... leads to the inescapable conclusion that it is only in name that there is any difference between authoritative hypnosis and most of the techniques of scientology. Many scientology techniques are in fact hypnotic techniques, and Hubbard has not changed their nature by changing their names.[52]

The Australian Church was forced to operate under the name of the "Church of the New Faith" as a result, the name and practice of Scientology having become illegal in the relevant states.[51] Several years of court proceedings aimed at overturning the ban followed.[51]

In the course of developing Scientology, Hubbard presented rapidly changing teachings that were often self-contradictory.[53][54] For the inner cadre of Scientologists in that period, involvement depended not so much on belief in a particular doctrine but on absolute, unquestioning faith in Hubbard.[53] In 1966 Hubbard stepped down as executive director of Scientology to devote himself to research and writing.[38][55] The following year, he formed the Sea Organization or Sea Org, which was to develop into an elite group within Scientology.[38][56] The Sea Org was based on three ships, the Diana, the Athena, and the Apollo, which served as the flag ship.[56] One month after the establishment of the Sea Org, Hubbard announced that he had made a breakthrough discovery, the result of which were the "OT III" materials purporting to provide a method for overcoming factors inhibiting spiritual progress.[56] These materials were first disseminated on the ships, and then propagated by Sea Org members reassigned to staff Advanced Organizations on land.[56]

In 1967 the IRS removed Scientology's tax-exempt status, asserting that its activities were commercial and operated for the benefit of Hubbard, rather than for charitable or religious purposes.[49] The decision resulted in a process of litigation that would be settled in the Church's favour a quarter of a century later, the longest case of litigation in IRS history.[39]

In 1979, as a result of FBI raids during Operation Snow White, eleven senior people in the church's Guardian's Office were convicted of obstructing justice, burglary of government offices, and theft of documents and government property. In 1981, Scientology took the German government to court for the first time.[57]

On January 1, 1982 Scientology established the Religious Technology Center (RTC) to oversee and ensure the standard application of Scientology technology.[58]

On November 11, 1982, the Free Zone was established by former top Scientologists in disagreement with RTC.[59] The Free Zone later became known as "Ron's Org" and was headed by former Hubbard Scientology Flagship Apollo Sea Org Captain "Bill" Robertson. The Free Zone Association was founded and registered under the laws of Germany.[60]

In 1983, in a unanimous decision, the High Court of Australia recognized Scientology as a religion in Australia, overturning restrictions that had limited activities of the church after the Anderson Report.[61]

On January 24, 1986, L. Ron Hubbard died at his ranch near San Luis Obispo, California and David Miscavige became the head of the organization.

Starting in 1991, persons connected with Scientology filed fifty lawsuits against the Cult Awareness Network (CAN), a group that had been critical of Scientology.[62] Although many of the suits were dismissed, one of the suits filed against the Cult Awareness Network resulted in $2 million in losses for the network.[62] Consequently, the organization was forced to go bankrupt.[62] In 1996, Steven L. Hayes, a Scientologist, purchased the bankrupt Cult Awareness Network's logo and appurtenances.[62][63] A new Cult Awareness Network was set up with Scientology backing, which operates as an information and networking center for non-traditional religions, referring callers to academics and other experts.[64][65]

In a 1993 U.S. lawsuit brought by the Church of Scientology against Steven Fishman, a former member of the Church, Fishman made a court declaration which included several dozen pages of formerly secret esoterica detailing aspects of Scientologist cosmogony.[66] As a result of the litigation, this material, normally strictly safeguarded and only used in Scientology's more advanced "OT levels", found its way onto the Internet.[66] This resulted in a battle between the Church of Scientology and its online critics over the right to disclose this material, or safeguard its confidentiality.[66] The Church of Scientology was forced to issue a press release acknowledging the existence of this cosmogony, rather than allow its critics "to distort and misuse this information for their own purposes."[66] Even so, the material, notably the story of Xenu, has since been widely disseminated and used to caricature Scientology, despite the Church's vigorous program of copyright litigation.[66]

Recognition as a religion

In December 1993, the Church of Scientology experienced a major breakthrough in its ongoing legal battles when the IRS granted full tax exemption to all Scientology Churches, missions and organizations.[67][68] Based on the IRS exemptions, the U.S. State Department formally criticized Germany for discriminating against Scientologists and began to note Scientologists' complaints of harassment in its annual human rights reports.[49]

In 1997, an open letter to then-German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, published as a newspaper advertisement in the International Herald Tribune, drew parallels between the "organized oppression" of Scientologists in Germany, and Nazi policies espoused by Germany in the 1930s.[69][70] The letter was signed by Dustin Hoffman, Goldie Hawn and a number of other Hollywood celebrities and executives.[70][71] Commenting on the matter, a spokesman for the U.S. Department of State said that Scientologists were discriminated against in Germany, but condemned the comparisons to the Nazis' treatment of Jews as extremely inappropriate, as did a United Nations Special Rapporteur.[71][72]

In 2000, the Italian Supreme Court ruled that Scientology is a religion for legal purposes.[73][74] In recent years, religious recognition has also been obtained in a number of other European countries, including Sweden,[8][75] Spain,[75][76] Portugal,[77] Slovenia,[75] Croatia[75] and Hungary,[75] as well as Kyrgyzstan[78] and Taiwan.[8] Other countries, notably Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Belgium and the United Kingdom, refuse to grant Scientology religious recognition.

Membership statistics

In 2005, the Church of Scientology stated its worldwide membership to be 8 million, although that number included people who took only the introductory course and did not continue on.[79] In 2007 a Church official claimed 3.5 million members in the United States,[80] but according to a 2001 survey published by the City University of New York, 55,000 people in the United States would, if asked to identify their religion, have stated Scientology.[81] In 2008, the same survey team estimated that only 25,000 Americans identify as Scientologists.[82]

Scientologists tend to disparage general religious surveys on the grounds that many members maintaining cultural and social ties to other religious groups will, when asked their religion, answer with their traditional and more socially acceptable affiliation. On the other hand, religious scholar J. Gordon Melton has said that the church's estimates of its membership numbers are significantly exaggerated.[83]

Beliefs and practices

Scientology claims that its beliefs and practices are based on rigorous research, and its doctrines are accorded a significance equivalent to that of scientific laws.[84] "Scientology works 100 percent of the time when it is properly applied to a person who sincerely desires to improve his life", the Church of Scientology says.[84] Conversion is held to be of lesser significance than the practical application of Scientologist methods.[84] Adherents are encouraged to validate the value of the methods they apply through their personal experience.[84] Hubbard himself put it this way: "For a Scientologist, the final test of any knowledge he has gained is, 'did the data and the use of it in life actually improve conditions or didn't it?'"[84]

Body and Spirit

Scientology beliefs revolve around the thetan, the individualized expression of the cosmic source, or life force, named after the Greek letter theta (θ).[85][86][87] The thetan is the true identity of a person – an intrinsically good, omniscient, non-material core capable of unlimited creativity.[85][86]

In the primordial past, thetans brought the material universe into being largely for their own pleasure.[85] The universe has no independent reality, but derives its apparent reality from the fact that most thetans agree it exists.[86] Thetans fell from grace when they began to identify with their creation, rather than their original state of spiritual purity.[85] Eventually they lost their memory of their true nature, along with the associated spiritual and creative powers. As a result, thetans came to think of themselves as nothing but embodied beings.[86][88]

Thetans are reborn time and time again in new bodies through a process called "assumption" which is analogous to reincarnation.[85] Like Hinduism, Scientology posits a causal relationship between the experiences of earlier incarnations and one's present life, and with each rebirth, the effects of the MEST universe (MEST here stands for matter, energy, space, and time) on the thetan become stronger.[85]

Emotions and the mind

Scientology presents two major divisions of the mind.[89] The reactive mind is thought to absorb all pain and emotional trauma, while the analytical mind is a rational mechanism which is responsible for consciousness.[86][90] The reactive mind stores mental images which are not readily available to the analytical (conscious) mind; these are referred to as engrams.[91] Engrams are painful and debilitating; as they accumulate, people move further away from their true identity.[85] To avoid this fate is Scientology's basic goal.[85] Dianetic auditing is one way by which the Scientologist may progress toward the Clear state, winning gradual freedom from the reactive mind's engrams, and acquiring certainty of his or her reality as a thetan.[88]

Scientology uses an emotional classification system called the tone scale.[92] The tone scale is a tool used in counseling; Scientologists maintain that knowing a person's place on the scale makes it easier to predict their actions and assists in bettering their condition.[93]

Survival and ethics

Scientology emphasizes the importance of survival, which it subdivides into eight classifications that are referred to as dynamics.[94][95] An individual's desire to survive is considered to be the first dynamic, while the second dynamic relates to procreation and family.[94][96] The remaining dynamics encompass wider fields of action, involving groups, mankind, all life, the physical universe, the spirit, and the Supreme Being.[94] The optimum solution to any problem is held to be the one that brings the greatest benefit to the greatest number of dynamics.[94]

Scientology teaches that spiritual progress requires and enables the attainment of high ethical standards.[97] In Scientology, rationality is stressed over morality.[97] Actions are considered ethical if they promote survival across all eight dynamics, thus benefiting the greatest number of people or things possible while harming the fewest.[98]

ARC and KRC triangles

The ARC and KRC triangles are concept maps which show a relationship between three concepts to form another concept. These two triangles are present in the Scientology symbol. The lower triangle, the ARC triangle, is a summary representation of the knowledge the Scientologist strives for.[85] It encompasses Affinity (affection, love or liking), Reality (consensual reality) and Communication (the exchange of ideas).[85] Scientologists believe that improving one of the three aspects of the triangle "increases the level" of the other two, but Communication is held to be the most important.[99] The upper triangle is the KRC triangle, the letters KRC positing a similar relationship between Knowledge, Responsibility and Control.[100]

In Scientology, social problems are ascribed to breakdowns in ARC – in other words, a lack of agreement on reality, a failure to communicate effectively, or a failure to develop affinity.[101] These can take the form of overts – harmful acts against another, either intentionally or by omission – which are usually followed by withholds – efforts to conceal the wrongdoing, which further increase the level of tension in the relationship.[101]

Social and antisocial personalities

While Scientology states that many social problems are the unintentional results of people's imperfections, it asserts that there are also truly malevolent individuals.[101] Hubbard believed that approximately 80 percent of all people are what he called social personalities – people who welcome and contribute to the welfare of others.[101] The remaining 20 percent of the population, Hubbard thought, were suppressive persons.[101] According to Hubbard, only about 2.5 percent of this 20 percent are hopelessly antisocial personalities; these make up the small proportion of truly dangerous individuals in humanity: "the Adolf Hitlers and the Genghis Khans, the unrepentant murderers and the drug lords."[101][102] Scientologists believe that any contact with suppressive or antisocial individuals has an adverse effect on one's spiritual condition, necessitating disconnection.[101][102]

In Scientology, defectors who turn into critics of the movement are declared suppressive persons,[103][104][105][106] and the Church of Scientology has a reputation for moving aggressively against such detractors.[107] A Scientologist who is actively in communication with a suppressive person and as a result shows signs of antisocial behaviour is referred to as a Potential Trouble Source.[108][109]

Auditing

Scientology asserts that people have hidden abilities which have not yet been fully realized.[110] It is believed that increased spiritual awareness and physical benefits are accomplished through counseling sessions referred to as auditing.[111] Through auditing, it is said that people can solve their problems and free themselves of engrams.[112] This restores them to their natural condition as thetans and enables them to be at cause in their daily lives, responding rationally and creatively to life events rather than reacting to them under the direction of stored engrams.[113] Accordingly, those who study Scientology materials and receive auditing sessions advance from a status of Preclear to Clear and Operating Thetan.[114] Scientology's utopian aim is to "clear the planet", a world in which everyone has cleared themselves of their engrams.[115]

Auditing is a one-on-one session with a Scientology counselor or auditor.[116] It bears a superficial similarity to confession or pastoral counseling, but the auditor does not dispense forgiveness or advice the way a pastor or priest might do.[116] Instead, the auditor's task is to help the person discover and understand engrams, and their limiting effects, for themselves.[116] Most auditing requires an E-meter, a device that measures minute changes in electrical resistance through the body when a person holds electrodes (metal "cans"), and a small current is passed through them.[112][116] Scientology asserts that watching for changes in the E-meter's display helps locate engrams.[116] Once an area of concern has been identified, the auditor asks the individual specific questions about it, in order to help them eliminate the engram, and uses the E-meter to confirm that the engram's "charge" has been dissipated and the engram has in fact been cleared.[116] As the individual progresses, the focus of auditing moves from simple engrams to engrams of increasing complexity.[116] At the more advanced OT auditing levels, Scientologists perform solo auditing sessions, acting as their own auditors.[116]

The Bridge to Total Freedom

Spiritual development within Scientology is accomplished by studying Scientology materials. Scientology materials (called Technology or Tech in Scientology jargon) are structured in sequential levels (or gradients), so that easier steps are taken first and greater complexities are handled at the appropriate time. This process is sometimes referred to as moving along the Bridge to Total Freedom, or simply the Bridge.[99] It has two sides: training and processing.[97] Training means education in the principles and practices of auditing.[97] Processing is personal development through participation in auditing sessions.[97]

The Church of Scientology believes in the principle of reciprocity, involving give-and-take in every human transaction.[6] Accordingly, members are required to make donations for study courses and auditing as they move up the Bridge, the amounts increasing as higher levels are reached.[6] Participation in higher-level courses on the Bridge may cost several thousand dollars, and Scientologists usually move up the Bridge at a rate governed by their income.[6]

Space opera and confidential materials

The Church of Scientology holds that at the higher levels of initiation (OT levels) mystical teachings are imparted that may be harmful to unprepared readers. These teachings are kept secret from members who have not reached these levels. The Church states that the secrecy is warranted to keep its materials' use in context, and to protect its members from being exposed to materials they are not yet prepared for.[117]

These are the OT levels, the levels above Clear, whose contents are guarded within Scientology. The OT level teachings include accounts of various cosmic catastrophes that befell the thetans.[118] Hubbard described these early events collectively as space opera.

In the OT levels, Hubbard explains how to reverse the effects of past-life trauma patterns that supposedly extend millions of years into the past.[119] Among these advanced teachings is the story of Xenu (sometimes Xemu), introduced as the tyrant ruler of the "Galactic Confederacy." According to this story, 75 million years ago Xenu brought billions of people to Earth in spacecraft resembling Douglas DC-8 airliners, stacked them around volcanoes and detonated hydrogen bombs in the volcanoes. The thetans then clustered together, stuck to the bodies of the living, and continue to do this today. Scientologists at advanced levels place considerable emphasis on isolating body thetans and neutralizing their ill effects.[120]

The material contained in the OT levels has been characterized as bad science fiction by critics, while others claim it bears structural similarities to gnostic thought and ancient Hindu myths of creation and cosmic struggle.[118][121] J. Gordon Melton suggests that these elements of the OT levels may never have been intended as descriptions of historical events, and that, like other religious mythology, they may have their truth in the realities of the body and mind which they symbolize.[118] He adds that on whatever level Scientologists might have received this mythology, they seem to have found it useful in their spiritual quest.[118]

The high-ranking OT levels are made available to Scientologists only by invitation, after a review of the candidate's character and contribution to the aims of Scientology.[112] Individuals who have read these materials may not disclose what they contain without jeopardizing their standing in the Church.[112] Excerpts and descriptions of OT materials were published online by a former member in 1995 and then circulated in mainstream media. This occurred after the teachings were submitted as evidence in court cases involving Scientology, thus becoming a matter of public record.[119][122] There are eight publicly known OT levels, OT I to VIII.[123] The highest level, OT VIII, is only disclosed at sea, on the Scientology cruise ship Freewinds.[123] It has been rumored that additional OT levels, said to be based on material written by Hubbard long ago, will be released at some appropriate point in the future.[124]

There is a large Church of Spiritual Technology symbol carved into the ground at Scientology's Trementina Base that is visible from the air.[125] Washington Post reporter Richard Leiby wrote, "Former Scientologists familiar with Hubbard’s teachings on reincarnation say the symbol marks a 'return point' so loyal staff members know where they can find the founder’s works when they travel here in the future from other places in the universe."[126]

Ceremonies

In Scientology, ceremonies for events such as weddings, child naming, and funerals are observed.[85] Friday services are held to commemorate the completion of a person's religious services during the prior week.[85] Ordained Scientology ministers may perform such rites.[85] However, these services and the clergy who perform them play only a minor role in Scientologists' religious lives.[127]

Influences

The general orientation of Hubbard's philosophy owes much to Will Durant, author of the popular 1926 classic The Story of Philosophy; Dianetics is dedicated to Durant.[128] Hubbard's view of a mechanically functioning mind in particular finds close parallels in Durant's work on Spinoza.[128]

Sigmund Freud's psychology, popularized in the 1930s and 1940s, was a key contributor to the Dianetics therapy model, and was acknowledged unreservedly as such by Hubbard.[129] Hubbard never forgot meeting Cmdr. Joseph Cheesman Thompson, a U.S. Navy officer who studied with Freud, when he was 12 years old,[130] and when he wrote to the American Psychological Association in 1949, he stated that he was conducting research based on the "early work of Freud".[131]

Another major influence was Alfred Korzybski's General Semantics.[129] Hubbard was friends with fellow science fiction writer A. E. van Vogt, who explored the implications of Korzybski's non-Aristotelian logic in works such as The World of Null-A, and Hubbard's view of the reactive mind has clear and acknowledged parallels with Korzybski's thought; in fact, Korzybski's "anthropometer" may have been what inspired Hubbard's invention of the E-meter.[129]

Beyond that, Hubbard himself named a great many other influences in his own writing – in Scientology 8-8008, for example, these include philosophers from Anaxagoras and Aristotle to Herbert Spencer and Voltaire, physicists and mathematicians like Euclid and Isaac Newton, as well as founders of religions such as Buddha, Confucius, Jesus and Mohammed – but there is little evidence in Hubbard's writings that he studied these figures to any great depth.[129]

As noted, there are elements of Eastern religions evident in Scientology,[131] in particular the concepts of karma, as present in Hinduism and in Jainism, and dharma.[132][133] In addition to the links to Hindu texts, Hubbard tried to connect Scientology with Taoism and Buddhism.[134] Scientology has been said to share features with Gnosticism as well.[135][136]

In the 1940s, Hubbard was in contact with Jack Parsons, a rocket scientist and member of the Ordo Templi Orientis then led by Aleister Crowley, and there have been suggestions that this connection influenced some of the ideas and symbols of Scientology.[137][138] Religious scholars like Gerald Willms and J. Gordon Melton have pointed out that Crowley's teachings bear little if any resemblance to Scientology doctrine.[137][138]

Organization

There are a considerable number of Scientology organizations (or orgs) which generally support one of the following three aims: enabling Scientology practice and training, promoting the wider application of Scientology technology, or campaigning for social change.[139] These organizations are supported by a three-tiered hierarchical structure comprising lay practitioners, staff and, at the top of the hierarchy, members of the so-called Sea Organization or Sea Org.[140] The Sea Org, comprising over 5,000 members, has been compared to the monastic orders found in other religions; it is composed of the most dedicated adherents, who work for nominal compensation and symbolically express their religious commitment by signing a billion-year contract.[140][141]

The internal structure of Scientology organizations is strongly bureaucratic, with detailed coordination of activities and collection of stats to measure organizational and individual performance.[140] Organizational operating budgets are performance-related and subject to frequent reviews.[140] Scientology has an internal justice system (the Ethics system) designed to deal with unethical or antisocial behavior.[140][142] Ethics officers are present in every org; they are tasked with ensuring correct application of Scientology technology and deal with violations such as non-compliance with standard procedures or any other behavior adversely affecting an org's performance, ranging from errors and misdemeanors to crimes and suppressive acts, as defined by internal documents.[143]

A controversial part of the Scientology justice system is the Rehabilitation Project Force (RPF).[143] When a Sea Org member is accused of a violation, such as lying, sexual misconduct, dereliction of duty, or failure to comply with Church policy, a Committee of Evidence examines the case.[143] If the charge is substantiated, the individual may accept expulsion from the Sea Org or participate in the RPF to become eligible to rejoin the Sea Org.[143] The RPF involves a daily regimen of five hours of auditing or studying, eight hours of work, often physical labor, such as building renovation, and at least seven hours of sleep.[143] Douglas E. Cowan and David G. Bromley state that scholars and observers have come to radically different conclusions about the RPF and whether it is "voluntary or coercive, therapeutic or punitive".[143]

Practice and training organizations

Many Scientologists' first contact with Scientology is through local informal groups and field auditors practicing Dianetics counseling.[144] In addition to these, Scientology operates hundreds of Churches and Missions around the world.[145] This is where Scientologists receive introductory training, and it is at this local level that most Scientologists participate.[145] Churches and Missions are licensed franchises; they offer services for a fee, and return a proportion of their income to the mother church.[145] They are also required to adhere to the standards established by the Religious Technology Center (RTC), which supervises the application of Scientology tech, owns the trademarks and service marks of Scientology, and collaborates with the Commodore's Messenger Organization to administer and control the various corporate entities within Scientology.[146][147] The RTC's Chairman is David Miscavige, who, while not the titular head of the Church of Scientology, is believed to be the most powerful person in the Scientology movement.[148]

Once an individual has reached Clear and wishes to proceed further, they can take OT auditing and coursework with Advanced Organizations located in Los Angeles, Sydney, East Grinstead and Copenhagen.[149] Beyond OT V, the Flag Service Organization in Clearwater, Florida offers the auditing and course work for OT levels VI and VII, while OT VIII is offered only by the Flag Ship Service Organization aboard the Scientology ship Freewinds.[150] Since 1981, all of these Churches and organizations have been united under the Church of Scientology International umbrella organization, with the Sea Org providing staff for all levels above the local Churches and Missions.[145][150]

Technology application organizations

A number of Scientology organizations specialize in promoting the use of Scientology technology as a means to solve social problems.

- Narconon is a drug education and rehabilitation program. The program is founded on Hubbard's belief that drugs and poisons stored in the body impede spiritual growth, and was originally conceived by William Benitez, a prison inmate who applied Hubbard's ideas to rid himself of his drug habit.[145][151] Narconon is offered in the United States, Canada and a number of European countries; its Purification Program uses a regimen composed of sauna, physical exercise, vitamins and diet management, combined with auditing and study.[145][151]

- Criminon is a program designed to rehabilitate criminal offenders by teaching them study and communication methods and helping them reform their lives.[145] The program originally grew out of the Narconon effort and today is available in over 200 prisons.[151] It has experienced steady growth, based on a good success rate, with low recidivism.[151]

- Applied Scholastics promotes the use of Hubbard's educational methodology, known as study tech.[152] Originally developed to help Scientologists study course materials, Hubbard's study tech is now used in some private and public schools as well.[153] Applied Scholastics is active across Europe and North America as well as in Australia, Malaysia, China and South Africa.[153] It supports literacy efforts in American cities and Third World countries, and its methodology is sometimes included in management training programs.[154]

- The Way to Happiness Foundation promotes a moral code written by Hubbard, to date translated into more than 40 languages.[152]

- The Association for Better Living and Education (ABLE) acts as an umbrella organization for these efforts.[155]

- The World Institute of Scientology Enterprises (WISE) is a not-for-profit organization which licenses Hubbard's management techniques for use in businesses.[152] The most prominent training supplier to make use of Hubbard's technology is Sterling Management Systems.[152]

The Church of Scientology has also instituted a Volunteer Ministers program to provide disaster relief; for example, Volunteer Ministers were active in the aftermath of 9/11, providing food and water and applying Scientology methods such as "Assists" to people in acute emotional distress.[156][157]

Social reform organizations

Some Scientology organizations are focused on bringing about social change.[152] One of these is the Citizens Commission on Human Rights (CCHR). Founded in 1969, it has a long history of opposing psychiatric practices such as lobotomy, electric shock treatment and the use of mood-altering drugs.[158][159] The psychiatric establishment rejected Hubbard's theories in the early 1950s.[159] Ever since, Scientology has argued that psychiatry suffers from the fundamental flaw of ignoring humanity's spiritual dimension, and that it fails to take Hubbard's insights about the nature of the mind into account.[158] Scientology holds psychiatry responsible for a great many wrongs in the world, saying it has at various times offered itself as a tool of political suppression and "that psychiatry spawned the ideology which fired Hitler's mania, turned the Nazis into mass murderers, and created the Holocaust."[158][159] In recent years, the CCHR has conducted high-profile campaigns against Ritalin, given to children to control hyperactivity, and Prozac, a commonly used antidepressant.[159] Neither drug was taken off the market as a result of the campaign, but Ritalin sales decreased, and Prozac suffered bad press.[159]

The main other organization in this field is the National Commission on Law Enforcement and Social Justice, devoted to combating what it describes as abusive practices by government and police agencies, especially Interpol.[159][160]

Other entities

Other prominent Scientology-related organizations include:

- International Association of Scientologists, the official Scientology membership organization.

- Church of Spiritual Technology, a non-profit organization that owns the copyrights to Scientology books.

Free Zone

Although Scientology is most often used as shorthand for the Church of Scientology, a number of groups practice Scientology and Dianetics outside of the official Church. These groups consist of both former members of the official Church of Scientology, as well as entirely new members. These groups are collectively known as the Free Zone. Capt. Bill Robertson, a former Sea Org member, was a primary instigator in the movement.[161] The Church labels these groups as squirrels in Scientology jargon, and often subjects them to considerable legal and social pressure.

Dispute of religion status

Scientology status by country

The Church of Scientology has pursued an extensive public relations campaign for the recognition of Scientology as a religion in the various countries in which it exists.[21][162][163] Opinions around the world still differ on whether Scientology is to be recognized as a religion or not,[164] and Scientology has often encountered opposition due to its strong-arm tactics directed against critics and members wishing to leave the organization.[104] A number of governments now view the Church as a religious organization entitled to protections and tax relief, while others continue to view it as a pseudoreligion or cult.[165][166] The differences between these classifications have become a major problem when discussing religions in general and Scientology specifically.[79]

Scientology is officially recognized as a religion in the United States.[7][8][9][10] Recognition came in 1993, when the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) stated that "[Scientology is] operated exclusively for religious and charitable purposes."[167][168]

The New York Times noted in this connection that the Church of Scientology had funded a campaign which included a whistle-blower organization to publicly attack the IRS, as well as the hiring of private investigators to look into the private lives of IRS officials.[49] In 1991, Mr. Miscavige, the highest-ranking Scientology leader, arranged a meeting with Fred T. Goldberg Jr., the Commissioner of the Internal Revenue Service at the time.[169] The meeting was an "opportunity for the church to offer to end its long dispute with the agency, including the dozens of suits brought against the IRS." The committee met several times with the Scientology legal team and "was persuaded that those involved in the Snow White crimes had been purged, that church money was devoted to tax-exempt purposes and that, with Mr. Hubbard's death, no one was getting rich from Scientology."[49] In August 1993, a settlement was reached; the church would receive its tax-exempt status and end its legal assault on the IRS and its personnel. The church was only required to resubmit new applications for exemption to the IRS exempt organizations division; the division was told "not to consider any substantive matters" because those issues had been resolved by the committee.[49] The secret agreement was announced on Oct. 13, 1993 with the IRS refusing to disclose any of the terms or the reasoning behind their decision.[49] Both the IRS and Scientology rejected any allegations of foul play or undue pressure having been brought to bear upon IRS officials, insisting that the decision had been based on the merits of the case.[170] IRS officials "insisted that Scientology's tactics had not affected the decision" and that "ultimately the decision was made on a legal basis".[49]

Elsewhere, Scientology has been able to obtain religious recognition in such countries as Australia,[8][171] Portugal,[172] Spain,[173][174] Slovenia,[75] Sweden,[75][175][176] Croatia,[75] Hungary[75] and Kyrgyzstan.[78] In New Zealand Scientology is recognized as a religious charity,[177] it has gained judicial recognition in Italy,[178] and its officials have won the right to perform marriages in South Africa.[74]

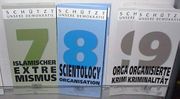

The Church has so far failed to win religious recognition in Canada.[74] In the UK, the Charity Commission for England and Wales ruled in 1999 that Scientology was not a religion and refused to register the Church as a charity, although a year later, it was recognized as a not-for-profit body in a separate proceeding by the UK Revenue and Customs and exempted from UK value added tax.[74][179] The German government takes the view that Scientology is a commercial, rather than religious organization, and has even gone so far as to consider a ban on Scientology, saying that the political goals of Scientology are incompatible with the German Constitution.[180] France and Belgium have not recognized Scientology as a religion, and Stephen A. Kent, writing in 2001, noted that no such recognition had been obtained in Ireland, Luxembourg, Israel and Mexico either.[181] The Belgian State Prosecution Service has recommended that various individuals and organizations associated with Scientology should be prosecuted.[182][183] An administrative court is to decide if charges will be pressed.[182][183] In Greece, Scientology is not recognized as a religion by the Greek government, and multiple applications for religious status have been denied, for example in 2000 and 2003.[184]

Scholarly views on Scientology's status as a religion

While acknowledging that a number of his colleagues accept Scientology as a religion, sociologist and professor Stephen A. Kent wrote: "Rather than struggling over whether or not to label Scientology as a religion, I find it far more helpful to view it as a multifaceted transnational corporation, only one element of which is religious" [emphasis in the original].[185][186] Kent also holds that the US government sees Scientology not as a religion, but as a charitable organization due to their religious claims.[187]

David G. Bromley of Virginia Commonwealth University characterizes Scientology as "a 'quasi-religious therapy' that resembles Freudian 'depth psychology' while also drawing upon Buddhism, Hinduism and Gnosticism."[188]

Dr. Frank K. Flinn, adjunct professor of religious studies at Washington University in St. Louis wrote, "it is abundantly clear that Scientology has both the typical forms of ceremonial and celebratory worship and its own unique form of spiritual life."[189] Flinn further states that religion requires "beliefs in something transcendental or ultimate, practices (rites and codes of behavior) that re-inforce those beliefs and, a community that is sustained by both the beliefs and practices," all of which are present within Scientology.[79]

Using the synonym of alternative religions, Barrett (1998:237) and Hunt (2003:195) place Scientology in the sociological grouping of personal development movements together with the Neurolinguistic Programming, Emin, and Insight. According to Religious Studies professor Mary Farrell Benarowski, Scientology describes itself as drawing on science, religion, psychology and philosophy but "had been claimed by none of them and repudiated, for the most part, by all."[190]

Describing the variety of scholarly opinions in existence, David G. Bromley and Douglas E. Cowan stated in 2006 that "Overall, however, most scholars have concluded that Scientology falls within the category of religion for the purposes of academic study, and a number have defended the Church in judicial and political proceedings on this basis."[127] Bromley and Cowan noted in 2008 that Scientology's attempts "to gain favor with new religion scholars" had often been problematic.[162]

Scientology as a commercial venture

While NRM scholars have generally accepted the religious nature of Scientology, media reports have tended to express the opinion that "Scientology is a business, often given to criminal acts, and sometimes masquerading as a religion."[127][191] During his lifetime, Hubbard was accused of using religion as a façade for Scientology to maintain tax-exempt status and avoid prosecution for false medical claims.[191] According to several of his fellow science fiction writers, Hubbard had on several occasions stated that the way to get rich was to start a religion.[192][193]

The Church of Scientology denounces the idea of Hubbard starting a religion for personal gain as an "unfounded rumor."[194] The Church also suggests that the origin of the "rumor" was a quote by George Orwell which had been "misattributed" to Hubbard.[195] Robert Vaughn Young, who left the Church in 1989 after being its spokesman for twenty years, suggested that reports of Hubbard making such a statement could be explained as a misattribution of Orwell, despite having encountered three of Hubbard's associates from his science fiction days who remembered Hubbard making statements of that sort in person.[196] It was Young who by a stroke of luck came up with the "Orwell quote": "... but I have always thought there might be a lot of cash in starting a new religion, and we'll talk it over some time..." It appears in a letter by George Orwell (signed Eric Blair) to a friend Jack Common, dated 16-February-38 (February 16, 1938), and was published in Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, vol. 1.[197] In 2006, Rolling Stone's Janet Reitman writes Hubbard said the same thing to science fiction writer Lloyd Eshbach, a fact quoted in Eshbach's autobiography.[198]

Scientology maintains strict control over the use of its symbols, icons, and names. It claims copyright and trademark over its "Scientology cross", and its lawyers have threatened lawsuits against individuals and organizations who have published the image in books and on Web sites. Because of this, it is very difficult for individual groups to attempt to publicly practice Scientology on their own, independent of the official Church of Scientology. Scientology has filed suit against a number of individuals who have attempted to set up their own auditing practices, using copyright and trademark law to shut these groups down.[199]

The Church of Scientology and its many related organizations have amassed considerable real estate holdings worldwide, likely in the hundreds of millions of dollars.[17] Scientology encourages existing members to "sell" Scientology to others by paying a commission to those who recruit new members.[17] Scientology franchises, or missions, must pay the Church of Scientology roughly 10% of their gross income.[200] On that basis, it is likened to a pyramid selling scheme.[201] While introductory courses do not cost much, courses at the higher levels may cost several thousand dollars each.[202]

In conjunction with the Church of Scientology's request to be officially recognized as a religion in Germany, around 1996 the German state Baden-Württemberg conducted a thorough investigation regarding the group's activities within Germany.[203] The results of this investigation indicated that at the time of publication, Scientology's main sources of revenue ("Haupteinnahmequellen der SO") were from course offerings and sales of their various publications. Course offerings ranged from (German Marks) DM 182.50 to about DM 30,000 – the equivalent today of approximately $119 to $19,560 USD. Revenue from monthly, bi-monthly, and other membership offerings could not be estimated in the report, but was nevertheless placed in the millions. Defending its practices against accusations of profiteering, the Church has countered critics by drawing analogies to other religious groups who have established practices such as tithing, or require members to make donations for specific religious services.[204]

In June 2006, it was announced at the Book Expo America that a Dianetics Racing Team had joined NASCAR. The Number 27 Ford Taurus driven by Kenton Gray in that year displayed a large Dianetics logo.[205][206]

Controversies

Of the many new religious movements to appear during the 20th century, the Church of Scientology has, from its inception, been one of the most controversial, coming into conflict with the governments and police forces of several countries (including the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada[209] and Germany).[1][17][196][210][211] It has been one of the most litigious religious movements in history, filing countless lawsuits against governments, organizations and individuals.[212]

Reports and allegations have been made, by journalists, courts, and governmental bodies of several countries, that the Church of Scientology is an unscrupulous commercial enterprise that harasses its critics and brutally exploits its members.[196][210] Time magazine published an article in 1991 which described Scientology as "a hugely profitable global racket that survives by intimidating members and critics in a Mafia-like manner."[17]

The controversies involving the Church and its critics, some of them ongoing, include:

- Scientology's disconnection policy, in which members are encouraged to cut off all contact with friends or family members who are "antagonistic" to Scientology.[213]

- The death of a Scientologist Lisa McPherson while in the care of the Church. (Robert Minton sponsored the multi-million dollar law suit against Scientology for the death of McPherson. In May 2004, McPherson's estate and the Church of Scientology reached a confidential settlement.)[214]

- Criminal activities committed on behalf of the Church or directed by Church officials (Operation Snow White, Operation Freakout).

- Conflicting statements about L. Ron Hubbard's life, in particular accounts of Hubbard discussing his intent to start a religion for profit and of his service in the military.[17]

- Scientology's harassment and litigious actions against its critics encouraged by its Fair Game policy.[17]

- Attempts to legally force search engines such as Google and Yahoo! to omit any webpages critical of Scientology from their search engines (and in Google's case, AdSense), or at least the first few search pages.[215]

- Allegations by former high-ranking Scientologists that David Miscavige beats and demoralizes staff and that physical violence by superiors towards staff working for them is a common occurrence in the church.[216][217] Scientology spokesman Tommy Davis denied these claims and provided witnesses to rebut them.[216]

- In October 2009, a French court found the Church of Scientology guilty of organized fraud. Four officers of the organization were fined and given suspended prison sentences of up to 2 years. The Church of Scientology said it would appeal the judgement. Prosecutors had hoped to achieve a ban of Scientology in France, but due to a temporary change in French law, which "made it impossible to dissolve a legal entity on the grounds of fraud", no ban was pronounced.[218]

- In November 2009, Australian Senator Nick Xenophon used a speech in Federal Parliament to allege that the Church of Scientology is a criminal organization. Based on letters from former followers of the religion, he said that there were "allegations of forced imprisonment, coerced abortions, and embezzlement of church funds, of physical violence and intimidation, blackmail and the widespread and deliberate abuse of information obtained by the organization ..."[219]

Due to these allegations, a considerable amount of investigation has been aimed at the Church, by groups ranging from the media to governmental agencies.[196][210]

Scientology social programs such as drug and criminal rehabilitation have likewise drawn both support and criticism.[220][221][222][223]

Professor of sociology Stephen A. Kent says "Scientologists see themselves as possessors of doctrines and skills that can save the world, if not the galaxy."[112] As stated in Scientology doctrine: "The whole agonized future of this planet, every man, woman and child on it, and your own destiny for the next endless trillions of years depend on what you do here and now with and in Scientology."[112] Kent has described Scientology's ethics system as "a peculiar brand of morality that uniquely benefited [the Church of Scientology] ... In plain English, the purpose of Scientology ethics is to eliminate opponents, then eliminate people's interests in things other than Scientology."[224] On the other hand, the sociologist David G. Bromley has noted that "a number of religious groups had radical and confrontational styles early in their history" and that "Scientology is now becoming less controversial."[225]

Scientology and the Internet

In the 1990s, Scientology representatives began to take action against increased criticism against Scientology on the Internet. The organization says that the actions taken were to prevent distribution of copyrighted Scientology documents and publications online, fighting what it refers to as "copyright terrorists".[226]

In January 1995, Church lawyer Helena Kobrin attempted to shut down the newsgroup alt.religion.scientology by sending a control message instructing Usenet servers to delete the group.[227] In practice, this rmgroup message had little effect, since most Usenet servers are configured to disregard such messages when sent to groups that receive substantial traffic, and newgroup messages were quickly issued to recreate the group on those servers that did not do so. However, the issuance of the message led to a great deal of public criticism by free-speech advocates.[228][229] Among the criticism raised, one suggestion is that Scientology's true motive is to suppress the free speech of its critics.[230][231]

The Church also began filing lawsuits against those who posted copyrighted texts on the newsgroup and the World Wide Web, and lobbied for tighter restrictions on copyrights in general. The Church supported the controversial Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act as well as the even more controversial Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Some of the DMCA's provisions (notably the Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act) were heavily influenced by Church litigation against US Internet service providers over copyrighted Scientology materials that had been posted or uploaded through their servers.

Beginning in the middle of 1996 and ensuing for several years, the newsgroup was attacked by anonymous parties using a tactic dubbed sporgery by some, in the form of hundreds of thousands of forged spam messages posted on the group. Some investigators said that some spam had been traced to Church members.[233][234] Former Scientologist Tory Christman later asserted that the Office of Special Affairs had undertaken a concerted effort to destroy alt.religion.scientology through these means; the effort failed.[235]

On January 14, 2008, a video produced by the Church of Scientology featuring an interview with Tom Cruise was leaked to the Internet and uploaded to YouTube.[236][237][238] The Church of Scientology issued a copyright violation claim against YouTube requesting the removal of the video.[239] Subsequently, the "Anonymous" group of internet users voiced its criticism of Scientology and began attacking the Church.[240] Calling the action by the Church of Scientology a form of Internet censorship, participants of Anonymous coordinated Project Chanology, which consisted of a series of denial-of-service attacks against Scientology websites, prank calls, and black faxes to Scientology centers.[241][242][243][244][245] On January 21, 2008, Anonymous announced its intentions via a video posted to YouTube entitled "Message to Scientology", and a press release declaring a "war" against both the Church of Scientology and the Religious Technology Center.[244][246][247] In the press release, the group stated that the attacks against the Church of Scientology would continue in order to protect the freedom of speech, and end what they saw as the financial exploitation of church members.[248]

On January 28, 2008, an Anonymous video appeared on YouTube calling for protests outside Church of Scientology centers on February 10, 2008.[249][250] According to a letter Anonymous e-mailed to the press, about 7,000 people protested in more than 90 cities worldwide.[251][252] Many protesters wore masks based on the character V from V for Vendetta (who was influenced by Guy Fawkes) or otherwise disguised their identities, in part to protect themselves from reprisals from the Church of Scientology.[253][254] Many further protests have followed since then in cities around the world.[255]

The Arbitration Committee of the Wikipedia internet encyclopedia decided in May 2009 to restrict access to its site from Church of Scientology IP addresses, to prevent self-serving edits by Scientologists.[256][257] A "host of anti-Scientologist editors" were topic-banned as well.[256][257] The committee concluded that both sides had "gamed policy" and resorted to "battlefield tactics", with articles on living persons being the "worst casualties".[256]

Scientology and hypnosis

Scientology literature states that L. Ron Hubbard demonstrated his professional expertise in hypnosis by "discovering" the Dianetic engram. Hubbard was said to be an accomplished hypnotist, and close acquaintances such as Forrest Ackerman (Hubbard's literary agent) and A. E. van Vogt (an early supporter of Dianetics) witnessed repeated demonstrations of his hypnotic skills.[192]

Auditing confidentiality

During the auditing process, the auditor may collect personal information from the person being audited.[258] Auditing records are referred to within Scientology as preclear folders.[259] The Church of Scientology has strict codes designed to protect the confidentiality of the information contained in these folders.[258] However, people leaving Scientology know that the Church is in possession of very personal information about them, and that the Church has a history of attacking and psychologically abusing those who leave it and become critics.[259] On December 16, 1969 a Guardian's Office order (G. O. 121669) by Mary Sue Hubbard authorized the use of auditing records for purposes of "internal security."[260] Some former members have said that while they were still in the Church, they combed through information obtained in auditing sessions to see if it could be used for smear campaigns against critics.[261][262] The Church of Scientology of California responded by stating that the letter which gave Mary Sue Hubbard authority to cull confessional files was not official policy and had been previously canceled. Charges that private information from auditing files has actually been used against individuals have not been upheld in court.[258]

Celebrities

Hubbard envisaged that celebrities would have a key role to play in the dissemination of Scientology, and in 1955 launched Project Celebrity, creating a list of 63 famous people that he asked his followers to target for conversion to Scientology.[263] Former silent-screen star Gloria Swanson and jazz pianist Dave Brubeck were among the earliest celebrities attracted to Hubbard's teachings.[263][264]

Today, Scientology operates eight churches that are designated Celebrity Centers, the largest of these being the one in Hollywood.[265] Celebrity Centers are open to the general public, but are primarily designed to minister to celebrity Scientologists.[265] Entertainers such as John Travolta, Kirstie Alley, Lisa Marie Presley, Nancy Cartwright, Jason Lee, Isaac Hayes, Tom Cruise, Chick Corea and Katie Holmes have generated considerable publicity for Scientology.[263]

See also

- Scientology and other religions

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Remember Venus?". Time Magazine. 1952-12-22. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,889564,00.html. Retrieved 2007-07-20.

- ↑ Melton, J. Gordon (1992). Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America. New York: Garland Pub. p. 190. ISBN 0-8153-1140-0.

- ↑ Guiley, Rosemary (1991). Harper's Encyclopedia of Mystical & Paranormal Experience. [San Francisco]: HarperSanFrancisco. p. 107. ISBN 0-06-250365-0.

- ↑ Neusner 2003, p. 227

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Melton 2000, pp. 28

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Melton 2000, pp. 59–60

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Finkelman, Paul (2006). Encyclopedia of American Civil Liberties. CRC Press. p. 287. ISBN 9780415943420. http://books.google.com/?id=YoI14vYA8r0C&pg=PA287&lpg=PA287&dq=%22Scientology+has+achieved+full+legal+recognition+as+a+religious+denomination+in+the+United+States%22. "Scientology has achieved full legal recognition as a religious denomination in the United States."

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Davis, Derek H. (2004). "The Church of Scientology: In Pursuit of Legal Recognition" (PDF). Zeitdiagnosen: Religion and Conformity. Münster, Germany: Lit Verlag. http://www.umhb.edu/files/academics/crl/publications/articles/the_church_of_scientologypursuit_of_legal_recognition.pdf. Retrieved 2008-05-10. "Many countries, including the United States, now give official recognition to Scientology as a religion [...]"

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lucy Morgan (29 March 1999). "Abroad: Critics public and private keep pressure on Scientology". St. Petersburg Times. "In the United States, Scientology gained status as a tax-exempt religion in 1993 when the Internal Revenue Service agreed to end a long legal battle over the group's right to the exemption."

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Toomey, Shamus (2005-06-26). "'TomKat' casts spotlight back on Scientology.", Chicago Sun-Times

- ↑ Willms 2009, p. 245. "Being a religion is one of the most important issues of Scientology's current self-representation."

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Koff, Stephen (1988-12-22). "Dozens of groups operate under auspices of Church of Scientology". St. Petersburg Times. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/sptimes/access/51440809.html?dids=51440809:51440809&FMT=FT&FMTS=ABS:FT. Retrieved 2008-09-30.

- ↑ Neusner 2003, p. 222

- ↑ Melton 2000, pp. 39–52

- ↑ Beit-Hallahmi, Benjamin (2003). "Scientology: Religion or racket?". Marburg Journal of Religion 8 (1): 1–11. http://www.uni-marburg.de/fb03/ivk/mjr/pdfs/2003/articles/breit2003.pdf.

- ↑ Marney, Holly (2007-05-20). "Cult or cure?". Opinion. Scotsman. http://news.scotsman.com/opinion.cfm?id=782292007. Retrieved 2009-01-04. "Labelled a cult by its critics, defended as a bona fide religion by devotees [...]"

Mallia, Joseph (1998-03-01). "Powerful church targets fortunes, souls of recruits". Inside the Church of Scientology. Boston Herald. http://www.apologeticsindex.org/s04a01.html. "It is just such tactics that cause critics to call the church – founded in 1953 – a cult and a money-grabbing machine that separates thousands of ordinary church members like Covarrubias from their free will and their money."

Huus, Kari (2005-07-05). "Scientology courts the stars". MSNBC. http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/8333804/print/1/displaymode/1098/. Retrieved 2009-01-04. "[...] Scientology, recognized by the federal government as a religious organization but denounced by critics as a cult that extracts tens of thousands of dollars from its followers." - ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 Behar, Richard (6 May 1991). "Scientology: The Thriving Cult of Greed and Power". Time Magazine. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,972865,00.html. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ↑ Palmer, Richard (1994-04-03). "Cult Accused of Intimidation". Sunday Times.

"Copyright – or wrong?". Salon Technology. http://www.salon.com/tech/feature/1999/07/22/scientology/index.html. "The Church of Scientology has determinedly fought to dismantle the Web sites that have republished its material all across the Net – using legal threats, filtering software and innumerable pro-Scientology posts in Usenet groups."

Kennedy, Dan (1996-04-19). "Earle Cooley is chairman of BU's board of trustees. He's also made a career out of keeping L. Ron Hubbard's secrets.". BU's Scientology Connection. Boston Phoenix. http://bostonphoenix.com/alt1/archive/specials/scientology/SCIENTOLOGY_1.html. Retrieved 2009-01-04. "The modern version of this scorched-earth policy is a virtual war on church critics who, like Lerma, post copyrighted church documents on the Net in an effort to expose it."

Sumi, Glenn (2006-10-12). "Managing Anger: Kenneth Anger speaks out on phones, artistic theft and Scientology". NOW Magazine. http://www.nowtoronto.com/issues/2006-10-12/movie_interview.php. Retrieved 2009-01-04. ""The Scientology people are very litigious," he says. "They're bulldogs who bite your ankle and won't give up, harassing people to death with lawsuits that go on and on.""

Welkos, Robert W.; Sappell, Joel (1990-06-29). "On the Offensive Against an Array of Suspected Foes". Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-scientology062990x,0,138179,full.story. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

Methvin, Eugene H. (May 1990). "Scientology: Anatomy of a Frightening Cult". Reader's Digest. pp. 1–6.

"Oral Questions to the Minister of State for the Home Office, 17 December 1996" Hansard, vol. 760, cols. 1392–1394 quote: "Baroness Sharples: Is my noble friend further aware that a number of those who have left the cult have been both threatened and harassed and many have been made bankrupt by the church?" - ↑ Sappell, Joel; Welkos, Robert W. (1990-06-24). "Defining the Theology". Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/news/local/la-scientologysidea062490,0,7631220,full.story. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ Ortega, Tony (2008-06-30). "Scientology's Crushing Defeat". Village Voice. http://www.villagevoice.com/content/printVersion/487758. Retrieved 2009-01-04. "Former members say that today the typical Scientologist must spend several years and about $100,000 in auditing before they find out on OT III that they are filled with alien souls that must be removed by further, even more expensive auditing."

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Kennedy, Dominic (2007-06-23). "'Church' that yearns for respectability". The Times (London). http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/comment/faith/article1975105.ece. Retrieved 2009-01-04. "Scientology is probably unique in that it keeps its sacred texts secret until, typically, devotees have paid enough money to learn what they say."

- ↑ Kent, Stephen A "Scientology – Is this a Religion?" (1999). Retrieved 24 November 2008.

- ↑ Cohen, David (23 October 2006). "Tom's aliens target City's 'planetary rulers'". Evening Standard.

- ↑ Cusack 2009, p. 394

- ↑ Benjamin J. Hubbard/John T. Hatfield/James A. Santucci An Educator's Classroom Guide to America's Religious Beliefs and Practices, p. 89, Libraries Unlimited, 2007 ISBN 978-1591584094

- ↑ The New Word original version available for download.

- ↑ The New Word, Publisher: Forgotten Books (February 7, 2008), ISBN 160506811X ISBN 978-1605068114

- ↑ Anastasius Nordenholz Scientology: Science of the Constitution and Usefulness of Knowledge, Freie Zone e. V., 1995 ISBN 978-3980472418

- ↑ The Encyclopedia of Christianity, Erwin Fahlbusch, Geoffrey W. Bromiley, page 556

- ↑ Kennedy, Shawn G. (1987-03-01). "Q AND A - New York Times". Query.nytimes.com. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B0DE2DE1E3CF932A35750C0A961948260. Retrieved 2009-01-12.

- ↑ Wilson, Bryan (1970). Religious Sects: A Sociological Study, McGraw-Hill, p. 163

- ↑ "Book: The Oxford Handbook of New Religious Movements By James R. Lewis, p. 110". Books.google.com. http://books.google.com/books?id=wpqKdDvLV0gC&pg=PA110&dq=dianetics&lr=&as_brr=3&as_pt=ALLTYPES#PPA110,M1. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ↑ Melton 2000, p. 4

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Melton 2000, pp. 9, 67

- ↑ Miller, Russell (1987). Bare-faced Messiah, The True Story of L. Ron Hubbard (First American ed.). New York: Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 0-8050-0654-0 page=151. http://www.xenu.net/archive/books/bfm/bfm09.htm.

- ↑ Wallis, Roy (1977). The Road to Total Freedom: A Sociological Analysis of Scientology, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0231042000]

- ↑ "Adult New York Times Best Seller Lists for 1950". Hawes.com. http://www.hawes.com/1950/1950.htm. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 38.4 38.5 38.6 38.7 38.8 Cowan & Bromley 2006, p. 172

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 Melton 2000, p. 13

- ↑ "Poor Man's Psychoanalysis?". Newsweek. 1950-11-06.

- ↑ Flowers 1984, p. 96–97

- ↑ Thomas Streissguth Charismatic Cult Leaders, p. 70, The Oliver Press Inc., 1996 ISBN 978-1881508182

- ↑ George Malko Scientology: the now religion, p. 58, Delacorte Press, 1970 ASIN B0006CAHJ6

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 Melton 2000, p. 10

- ↑ Christian D. Von Dehsen-Scott L. Harris Philosophers and Religious Leaders, p. 90, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1999 ISBN 978-1573561525

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Miller, Russell (1987). Bare-faced Messiah, The True Story of L. Ron Hubbard (First American ed.). New York: Henry Holt & Co. ISBN 0-8050-0654-0 pages=140–142. http://www.xenu.net/archive/books/bfm/bfm13.htm.

- ↑ Melton 2000, p. 11

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Melton 2000, p. 12

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 49.5 49.6 49.7 Frantz, Douglas (1997-03-09). "Scientology's Puzzling Journey From Tax Rebel to Tax Exempt". New York Times. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9B05E7DE1639F93AA35750C0A961958260&sec=&spon=&pagewanted=all. Retrieved 2008-10-26.

- ↑ "1963 FDA raid". Cs.cmu.edu. 1963-01-04. http://www.cs.cmu.edu/~dst/E-Meter/Mark-VII/. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 Melton 2000, p. 14

- ↑ Anderson, Kevin Victor, Q.C.; Victoria Board of Enquiry into Scientology (1965). Report of the Board of Enquiry into Scientology. Melbourne: Government Printer. p. 155.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Lindholm, Charles (1992). "Charisma, Crowd Psychology and Altered States of Consciousness". Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry (Kluwer Academic Publishers) 16 (3): 287–310. doi:10.1007/BF00052152.

- ↑ Wallis, Roy (1977). The Road to Total Freedom. New York: Columbia University Press. p. 153.

- ↑ Neusner 2003, p. 225

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 Melton 2000, p. 17

- ↑ Elisabeth Amveck Researching New Religious Movements, p. 261, Routledge, 2006 ISBN 978-0415277549

- ↑ Lewis & Hammer 2007, p. 24

- ↑ William W. Zellner Extraordinary Groups, p. 295, Macmillan, 2007 ISBN 978-0716770343

- ↑ "Freie Zone". Scientologie.org. 2001-12-13. http://www.scientologie.org/gif/wip-decision.pdf. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ↑ Melton 2000, pp. 14–15

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 62.2 62.3 Knapp, Dan (19 December 1996). "Group that once criticized Scientologists now owned by one". CNN (Time Warner). http://www.cnn.com/US/9612/19/scientology/index.html. Retrieved 2007-10-29.

- ↑ Russell, Ron (1999-09-09). "Scientology's Revenge - For years, the Cult Awareness Network was the Church of Scientology's biggest enemy. But the late L. Ron Hubbard's L.A.-based religion cured that–by taking it over". New Times LA.

- ↑ "Book: Cults: A Reference Handbook By James R. Lewis, Published by ABC-CLIO, 2005, ISBN 1851096183, 9781851096183". Books.google.co.uk. http://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&id=aqmbnfXCzn0C&dq=Lewis++cults+reference+handbook&printsec=frontcover&source=web&ots=9V_fdrgIdd&sig=LOVhKSCubo2WEKr48ef-o8mKCwI&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA299,M1. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ↑ Goodman, Leisa, Human Rights Director, Church of Scientology International (2001). "A Letter from the Church of Scientology". Marburg Journal of Religion: Responses From Religions: pp. Volume 6, No. 2, 4 pages. http://web.uni-marburg.de/religionswissenschaft/journal/mjr/goodman.html. Retrieved 2007-10-28.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 66.4 Dawson, Lorne L.; Cowan, Douglas E. (2004). Religion Online. New York, NY/London, UK: Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 262, 264–265. ISBN 0415970229. http://books.google.com/?id=88vcFt6rOigC&pg=PA264&dq=Scientology+xenu+internet+OT

- ↑ Phillip Lucas New Religious Movements in the 21st Century, p. 235, Routledge, 2004 ISBN 978-0415965774

- ↑ Internal Revenue Service (1993). "Form 906 - Closing Agreement On Final Determination Covering Specific Matters". http://www.xenu.net/archive/IRS/#VIII. Retrieved 2010-05-28.

- ↑ Schmid, John (1997-01-15). German Party Replies To Scientology Backers, Herald Tribune

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Germany, America and Scientology, Washington Post, February 1, 1997

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Bonfante, Jordan; van Voorst, Bruce (1997-02-10). "Does Germany Have Something Against These Guys?", Time

- ↑ Staff (1998-04-02). "U.N. Derides Scientologists' Charges About German 'Persecution'", New York Times

- ↑ "Italian Supreme Court decision". Cesnur.org. http://www.cesnur.org/testi/scie_march2000.htm. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 Cowan & Bromley 2006, p. 185

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 75.4 75.5 75.6 75.7 75.8 La justice espagnole accorde à la Scientologie le statut de religion, 2008-01-09, Le Monde: "L'Eglise de scientologie s'installe peu à peu dans le paysage cultuel européen. Après la Suède, le Portugal, la Slovénie, la Croatie ou la Hongrie, la justice espagnole vient à son tour d'inscrire la scientologie au registre légal des religions. Cette inscription, intervenue le 19 décembre, fait suite à une décision de l'Audience nationale, la plus haute juridiction espagnole." ("The Church of Scientology is slowly establishing itself in the European religious landscape. After Sweden, Portugal, Slovenia, Croatia and Hungary, it was now the turn of the Spanish legal system to add Scientology to the official register of religions. The registration, which took place on 19 December, followed a decision by the Audiencia Nacional, the highest court of Spain.")

- ↑ La Audiencia Nacional reconoce a la Cienciología como iglesia, 2007-11-01, El País

- ↑ "2007 U.S. Department of State – 2007 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices: Portugal". State.gov. 2008-03-11. http://www.state.gov/g/drl/rls/hrrpt/2007/100579.htm. Retrieved 2010-09-04.