Heinrich Schliemann

| Heinrich Schliemann | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Heinrich Schliemann

|

|

| Born | January 6, 1822 Neubukow |

| Died | December 26, 1890 Naples |

| Nationality | German |

| Fields | Archaeology |

Heinrich Schliemann (German pronunciation: [ˈʃliːman]; (January 6, 1822, Neubukow, Mecklenburg-Schwerin – December 26, 1890, Naples) was a German businessman and archaeologist, and an advocate of the historical reality of places mentioned in the works of Homer. Schliemann was an important archaeological excavator of Troy, along with the Mycenaean sites Mycenae and Tiryns. His successes lent material weight to the idea that Homer's Iliad and Virgil's Aeneid reflect actual historical events.

Contents |

Childhood, youth, and life as a businessman

Schliemann was born in Neubukow in 1822. His father, Ernst Schliemann, was a poor Protestant minister. Heinrich's mother, Luise Therese Sophie, died in 1831, when Heinrich was nine years old. After his mother's death, his father sent Heinrich to live with his uncle. When he was eleven years old, his father paid for him to enroll in the Gymnasium (grammar school) at Neustrelitz. Heinrich's later interest in history was initially encouraged by his father, who had schooled him in the tales of the Iliad and the Odyssey and had given him a copy of Ludwig Jerrer's Illustrated History of the World for Christmas in 1829. According to his diary, Schliemann's interest in ancient Greece was conceived when he overheard a university student reciting the Odyssey of Homer in classical Greek; Heinrich was taken by the language's beauty. Schliemann later claimed that at the age of 8, he had declared he would one day excavate the city of Troy.

However, Heinrich had to transfer to the Realschule (vocational school) after his father was accused of embezzling church funds[1] and had to leave that institution in 1836 when his father was no longer able to pay for it. His family's poverty made a university education impossible, so it was Schliemann's early academic experiences that influenced the course of his education as an adult. He wanted to return to the educated life, to reacquire and explore the interests he had been deprived of in childhood. In his archaeological career, however, there was often a division between Schliemann and the educated professionals.

At age 14, after leaving Realschule, Heinrich became an apprentice at Herr Holtz's grocery in Fürstenberg. One story has it that his passion for Homer was born when he heard a drunkard reciting it at the grocer's.[2] He labored for five years, until he was forced to leave because he burst a blood vessel lifting a heavy barrel.[3] In 1841, Schliemann moved to Hamburg and became a cabin boy on the Dorothea, a steamer bound for Venezuela. After twelve days at sea, the ship foundered in a gale. The survivors washed up on the shores of the Netherlands.[4] Schliemann became a messenger, office attendant, and later, a bookkeeper in Amsterdam.

On March 1, 1844, 22-year old Schliemann took a position with B. H. Schröder & Co., an import/export firm. There, he displayed such talent that they sent him as a General Agent in 1846 to St. Petersburg. There, the markets were favorable. In time, Schliemann represented a number of companies. He continued to nourish a passion for the Homeric story and an ambition to become a great linguist. He learned Russian and Greek, employing a system that he used his entire life to learn languages—Schliemann claimed that it took him six weeks to learn a language[5] and wrote his diary in the language of whatever country he happened to be in.

By the end of his life, he could converse in English, French, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, Swedish, Italian, Greek, Latin, Russian, Arabic, and Turkish as well as German. Schliemann's ability with languages was an important part of his career as a businessman in the importing trade. In 1850, Heinrich learned of the death of his brother, Ludwig, who had become wealthy as a speculator in the California gold fields. Schliemann went to California in early 1851 and started a bank in Sacramento. The bank bought and resold over a million dollars of gold dust in just six months. Prospectors could mine or pan for the gold, but they had no way to sell it except to middlemen such as Schliemann, who made quick fortunes on the exchanges.

Schliemann also amassed a large fortune speculating on various stock markets prior to the California Gold Rush, adding to his already considerable fortune. While he was there, California became the 31st state in September 1850 and Schliemann acquired United States citizenship.

According to his memoirs, before arriving in California he dined in Washington with President Millard Fillmore and his family,[6] but there is no mention of this in the official presidential records. He also published an account of the San Francisco fire of 1851.

Schliemann was not in the United States long. Rather suddenly, on April 7, 1852, he sold his business and returned to Russia. There he attempted to live the life of a gentleman, which brought him into contact with Ekaterina Lyschin, the niece of one of his wealthy friends. Schliemann had previously learned his childhood sweetheart, Minna, had married.

Heinrich and Ekaterina married on October 12, 1852. The marriage was troubled from the start. Ekaterina wanted him to be richer than he was and withheld conjugal rights until he made a move in that direction. Schliemann cornered the market in indigo (an important dye) and then went into the indigo business itself, turning a good profit. Ekaterina and Heinrich had a son, Sergey. Two other children followed.

Having a family to support motivated Schliemann to attend to business even though he still had his first fortune. He found a way to make yet another quick fortune as a military contractor in the Crimean War, 1854-1856. He cornered the market in saltpeter, sulfur, and lead, constituents of ammunition, which he resold to the Russian government.

By 1858, Schliemann was wealthy enough to retire. Some say he retired at 36, which would have been in 1858; others say 1863, at age 41. In his memoirs, he claimed that he wished to dedicate himself to the pursuit of Troy, whenever the exact date of the completion of his business career.

Life as an archaeologist

Schliemann's first interest of a classical nature seems to have been the location of Troy. The city's very existence was then in dispute. Perhaps his attention was attracted by the first excavations at Santorini in 1862 by Ferdinand Fouqué. This possibility argues for an early retirement date, as he was already an international traveller by then. He may have been inspired by Frank Calvert, whom he met on his first visit to the Hissarlik site in 1868.

Somewhere in his many travels and adventures, Schliemann lost Ekaterina. She was not interested in adventure and had remained in Russia. Schliemann claimed to have utilised the divorce laws of Indiana in 1869. Using Indiana's lax divorce laws enabled Schliemann to divest himself of his Russian wife Ekaterina in absentia.[7]

Based on the work of a British archaeologist, Frank Calvert, who had been excavating the site in Turkey for over 20 years, Schliemann decided that Hissarlik was, in fact, the site of Troy. In 1868 — a busy year for Schliemann — he visited sites in the Greek world, published Ithaka, der Peloponnesus und Troja in which he asserted that Hissarlik was the site of Troy, and submitted a dissertation in ancient Greek proposing the same thesis to the University of Rostock. He received a PhD in 1869[8] from the university of Rostock for that submission. Regardless of his previous interests and adventures, Schliemann's course was set. He would take over Calvert's excavations on the eastern half of the Hissarlik site, which was on Calvert's property. The Turkish government owned the western half. Calvert became Schliemann's collaborator and partner.

Schliemann brought dedication, enthusiasm, conviction and his not inconsiderable fortune to the work. Excavations cannot be made without funds, and are vain without publication of the results. Schliemann was able to provide both. Consequently, he made his name in the field of Mycenaean archaeology. Despite later criticism, his work continues to receive great attention and favor from some Classical archaeologists to this day.

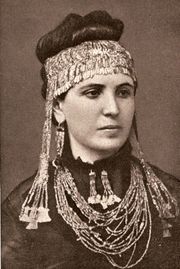

Schliemann knew he would need an assistant who was knowledgeable in matters pertaining to Greek culture. As he had divorced Ekaterina in 1869, he was able to advertise for a wife: which he did, in a newspaper in Athens. A friend, the Archbishop of Athens, suggested a relative of his, the seventeen-year-old Sophia Engastromenos (1852–1932). Schliemann soon married her in October 1869. They later had two children, Andromache and Agamemnon Schliemann; he reluctantly allowed them to be baptized, but only solemnized the ceremony by placing a copy of the Iliad on the children's heads and reciting one hundred hexameters.

By 1871, Schliemann was ready to go to work at Troy.

His career began before archaeology developed as a professional field, so, by present standards, the field technique of Schliemann's work leaves much to be desired. Thinking that Homeric Troy must be in the lowest level, Schliemann and his workers dug hastily through the upper levels, reaching fortifications that he took to be his target. In 1872, he and Calvert fell out over this method. Schliemann flew into a fury when Calvert published an article stating that the Trojan War period was missing from the site's archaeological record.

As if to confirm Schliemann's views, a cache of gold appeared in 1873; Schliemann named it "Priam's Treasure". He later wrote that he had seen the gold glinting in the dirt and dismissed the workmen so that he and Sophie could excavate it themselves, removing it in her shawl. Schliemann was successful in creating public interest in antiquity. Sophie later wore "the Jewels of Helen" for the public. Schliemann published his findings in 1874, in Trojanische Altertümer ("Trojan Antiquities").

This publicity backfired when the Turkish government revoked Schliemann's permission to dig and sued him for a share of the gold. Collaborating with Calvert, Schliemann had smuggled the treasure out of Turkey, alienating the Turkish authorities. He defended his "smuggling" in Turkey as an attempt to protect the items from corrupt local officials. Priam's Treasure today remains a subject of international dispute.

Schliemann published Troja und seine Ruinen (Troy and Its Ruins) in 1875 and excavated the Treasury of Minyas at Orchomenus. In 1876, he began digging at Mycenae. Upon discovering the Shaft Graves, with their skeletons and more regal gold (including the Mask of Agamemnon), Schliemann cabled the king of Greece. The results were published in Mykena in 1878.

Although he had received permission in 1876 to continue excavation, Schliemann did not reopen the dig at Troy until 1878–1879, after another excavation in Ithaca designed to locate an actual site mentioned in the Odyssey. This was his second excavation at Troy. Emile Burnouf and Rudolph Virchow joined him there in 1879. Schliemann made a third excavation at Troy in 1882–1883, an excavation of Tiryns with Wilhelm Dörpfeld in 1884, and yet again, a fourth excavation at Troy, also with Dörpfeld (who emphasized the importance of strata), in 1888–1890.

Death

On August 1, 1890, Schliemann returned reluctantly to Athens, and in November traveled to Halle for an operation on his chronically infected ears. The doctors dubbed the operation a success, but his inner ear became painfully inflamed. Ignoring his doctors' advice, he left the hospital and traveled to Leipzig, Berlin, and Paris. From the latter, he planned to return to Athens in time for Christmas, but his ears became even worse. Too sick to make the boat ride from Naples to Greece, Schliemann remained in Naples, but managed to make a journey to the ruins of Pompeii. On Christmas Day he collapsed into a coma and died in a Naples hotel room on December 26, 1890. His corpse was then transported by friends to the First Cemetery in Athens. It was interred in a mausoleum shaped like a temple erected in ancient Greek style designed by Ernst Ziller in the form of a pedimental sculpture. The frieze circling the outside of the mausoleum shows Schliemann conducting the excavations at Mycenae and other sites. His magnificent residence in the city centre of Athens, houses today the Numismatic Museum of Athens.

Criticisms

Schliemann's work left much to be desired. Further excavation of the Troy site by others indicated that the level he named the Troy of the Iliad was not that, although they retain the names given by Schliemann. His excavations were even condemned by later archaeologists as having destroyed the main layers of the real Troy. However, before Schliemann, not many people even believed in a real Troy, and those who did were divided about where to look for it. Charles Maclaren had pointed to Hissarlik as the location of Troy as early as 1822, but many other locations had been suggested. Kenneth W. Harl in the Teaching Company's Great Ancient Civilizations of Asia Minor lecture series sarcastically claims that Schliemann's excavations were carried out with such rough methods that he did to Troy what the Greeks couldn't do in their times, destroying and leveling down the entire city walls to the ground.

One of the main problems of his work is that King Priam's Treasure was putatively found in the Troy II level, of the primitive Early Bronze Age, long before Priam's city of Troy VI or Troy VIIa in the prosperous and elaborate Mycenaean Age. Moreover, the finds were unique. These unique and elaborate gold artifacts do not appear to belong to the Early Bronze Age. But given that the age of the Trojan War was Schliemann's main aim and that he did not really consider the possibility that there had been several cities one after another on the site, it is hardly surprising that he called the spectacular find "Priam's Treasure".

In the 1960s William Niederland, a psychoanalyst, conducted a psychobiography of Schliemann to account for his unconscious motives. Niederland read thousands of Schliemann's letters and found that he resented his father and blamed him for his mother's death, as evidenced by vituperative letters to his sisters. According to Niederland Schliemann's preoccupation (as he saw it) with graves and the dead reflected grief over the loss of his home and his efforts at resurrecting the Homeric dead should represent a restoration of his mother and nothing specifically in the early letters indicate that he was interested in Troy or classical archaeology. Whether this sort of evaluation is valid is debatable. He was accused of not always being scrupulous about providing the whole truth and that his father's experiences gave him a sympathy to means that were not always legal or aboveboard (he has been accused of forging documents to divorce his wife and fill in false facts in his application for US citizenship). He is also accused of being a black market trader, though several documentaries from the late 80s and early 90s prefer to gloss over this accusation.

In 1972, Professor William Calder of the University of Colorado, speaking at a commemoration of Schliemann's birthday, claimed that he had uncovered several possible untruths. Other investigators followed, such as Professor David Traill of the University of California. Schliemann has been accused of embellishing his stories. As mentioned above, Schliemann claimed in his memoirs to have dined with President Millard Fillmore in the White House in 1850. However, newspapers of the day make no mention of such a meeting. Schliemann left California hastily to escape from his business partner, with whom he had conflicts. In the frontier society of the Gold Rush, cheating was punishable by lynching. He has been accused of lying, with regard to his claim that he had become a U.S. citizen in 1850 while in California; supposedly, he was granted citizenship while in New York City instead in 1868. He has also been suspected of being granted citizenship at that time and place on the basis of his false claim that he had been a long-time resident. The worst accusation against Schliemann, by academic standards, is that he may have fabricated Priam's Treasure, or at least combined several disparate finds. His servant, Yannakis, claimed that he found some of it in a tomb some distance away, and that it contained no gold. However, recent examination of the actual artifacts in a museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, where they were taken as loot during the Second World War and later re-exhibited, has shown the artifacts to be genuine.

In literature

Fiction: "Nightfall" (1941) by Isaac Asimov. "We've located series of civilizations, nine of them definitely, and indications of others as well, all of which have reached heights comparable to our own, and all of which, without exception, were destroyed by fire at the very height of their culture."

Biographical novel: The Greek Treasure (1975) by Irving Stone.

Fiction: Uhura's Song (Star Trek 21), by Janet Kagan. In the story, the Enterprise crew searches for a forgotten civilization of felinoids by following a song of their descendants. The character Evan Wilson brings up Heinrich Schliemann as a reason to follow the song, and when questioned as to who he is, says that he found Troy on the strength of a song.[9] "Heinrich Schliemann" thus becomes a catchphrase on the ship, giving a morale boost to the crew.

Works

- La Chine et le Japon au temps présent (1867)

- Ithaka, der Peloponnesus und Troja (1868) (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01682-7)

- Trojanische Altertümer: Bericht über die Ausgrabungen in. Troja (1874) (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01703-9)

- Troja und seine Ruinen (1875). Translated into EnglishTroy and its Remains (1875) (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01717-6)

- Mykena (1878). Translated into English Mycenae: A Narrative of Researches and Discoveries at Mycenae and Tiryns (1878) (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01692-6)

- Ilios, City and Country of the Trojans (1880) (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01679-7)

- Orchomenos: Bericht über meine Ausgrabungen in Böotischen Orchomenos (1881) (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01718-3)

- Tiryns: Der prähistorische Palast der Könige von Tiryns (1885) (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01720-6). Translated into English Tiryns: The Prehistoric Palace of the Kings of Tiryns (1885)

- Bericht über de Ausgrabungen in Troja im Jahre 1890 (1891) (reissued by Cambridge University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1-108-01719-0).

See also

- National Archaeological Museum of Athens

- Numismatic Museum of Athens

- Mask of Agamemnon

- Priam's Treasure

- Troy

References

- ↑ Robert Payne, The Gold of Troy: The Story of Heinrich Schliemann and the Buried Cities of Ancient Greece, 1959, repr. New York: Dorset, 1990, p. 15.

- ↑ Payne, p. 70.

- ↑ "Schliemann, Heinrich" in Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie, at de.wikisource. (German)

- ↑ Payne, p. 25.

- ↑ Payne, p. 30.

- ↑ Leo Deuel, Memoirs of Heinrich Schliemann: A Documentary Portrait Drawn from his Autobiographical Writings, Letters, and Excavation Reports, New York: Harper, 1977, ISBN 0060111062, p. 67; he also mentions meeting President Andrew Johnson, p. 126.

- ↑ Indiana Historical Society - Manuscripts and Archives Department. Heinrich Schliemann Papers,1869-1960: Collection # M 0378. Catalog.

- ↑ Bernard, Wolfgang. Homer-Forschung zu Schliemanns Zeit und heute at the Wayback Machine (archived June 9, 2007). (in German).

- ↑ p. 38: "I think you're as crazy as Heinrich Schliemann—and you know what happened to him!"

Sources

- Boorstin, Daniel (1983). The Discoverers. Random House. ISBN 0394402294.

- Durant, Will (1939). The Life of Greece: Being a history of Greek civilization from the beginnings, and of civilization in the Near East from the death of Alexander, to the Roman conquest. Simon & Schuster. OCLC 355696346.

- Poole, Lynn; Poole, Gray (1966). One Passion, Two Loves. Crowell. OCLC 284890..

- Silberman, Neil Asher (1990). Between Past and Present: Archaeology, Ideology, and Nationalism in the Modern Middle East. New York: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-41610-5.

- Tolstikov, Vladimir; Treister, Mikhail (1996). The Gold of Troy. Searching for Homer's Fabled City. Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0810933942.

- Traill, David A. (1995). Schliemann of Troy: Treasure and Deceit. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 0-312-14042-8.

- Wood, Michael (1987). In Search of the Trojan War. New American Library. ISBN 0-452-25960-6.

External links

- American School of Classical Studies at Athens. Heinrich Schliemann and Family Papers at the Wayback Machine (archived October 5, 2007)..

Media related to Heinrich Schliemann at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Heinrich Schliemann at Wikimedia Commons Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Schliemann, Heinrich". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). "Schliemann, Heinrich". Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.