Schizophrenia

| Schizophrenia | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Cloth embroidered by a schizophrenia patient giving a look into her state of mind. |

|

| ICD-10 | F20. |

| ICD-9 | 295 |

| OMIM | 181500 |

| DiseasesDB | 11890 |

| MedlinePlus | 000928 |

| eMedicine | med/2072 emerg/520 |

| MeSH | F03.700.750 |

Schizophrenia (pronounced /ˌskɪtsɵˈfrɛniə/ or /ˌskɪtsɵˈfriːniə/) is a serious mental illness characterized by a disintegration of the process of thinking and of emotional responsiveness.[1] It most commonly manifests as auditory hallucinations, paranoid or bizarre delusions, or disorganized speech and thinking with significant social or occupational dysfunction. Onset of symptoms typically occurs in young adulthood,[2] with around 1.5% lifetime prevalence[3][4] of the population affected. Diagnosis is based on the patient's self-reported experiences and observed behavior. No laboratory test for schizophrenia currently exists.[5]

Studies suggest that genetics, early environment, neurobiology, psychological and social processes are important contributory factors; some recreational and prescription drugs appear to cause or worsen symptoms. Current psychiatric research is focused on the role of neurobiology, but no single organic cause has been found. As a result of the many possible combinations of symptoms, there is debate about whether the diagnosis represents a single disorder or a number of discrete syndromes. Despite the etymology of the term from the Greek roots skhizein (σχίζειν, "to split") and phrēn, phren- (φρήν, φρεν-; "mind"), schizophrenia does not imply a "split mind" and it is not the same as dissociative identity disorder (formerly called multiple personality disorder or split personality), a condition with which it is often confused in public perception.[6]

Increased dopamine activity in the mesolimbic pathway of the brain is commonly found in people with schizophrenia. The mainstay of treatment is antipsychotic medication; this type of drug primarily works by suppressing dopamine activity. Dosages of antipsychotics are generally lower than in the early decades of their use. Psychotherapy, and vocational and social rehabilitation are also important. In more serious cases—where there is risk to self and others—involuntary hospitalization may be necessary, although hospital stays are less frequent and for shorter periods than they were in previous times.[7]

The disorder is thought to mainly affect cognition, but it also usually contributes to chronic problems with behavior and emotion. People with schizophrenia are likely to have additional (comorbid) conditions, including major depression and anxiety disorders;[8] the lifetime occurrence of substance abuse is around 40%. Social problems, such as long-term unemployment, poverty and homelessness, are common. Furthermore, the average life expectancy of people with the disorder is 10 to 12 years less than those without, due to increased physical health problems and a higher suicide rate (about 5%).[9][10]

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

A person diagnosed with schizophrenia may experience hallucinations (most commonly hearing voices), delusions (often bizarre or persecutory in nature), and disorganized thinking and speech. The latter may range from loss of train of thought, to sentences only loosely connected in meaning, to incoherence known as word salad in severe cases. There is often an observable pattern of emotional difficulty, for example lack of responsiveness or motivation. Impairment in social cognition is associated with schizophrenia, as are symptoms of paranoia, and social isolation commonly occurs. In one uncommon subtype, the person may be largely mute, remain motionless in bizarre postures, or exhibit purposeless agitation; these are signs of catatonia.

Late adolescence and early adulthood are peak years for the onset of schizophrenia. In 40% of men and 23% of women diagnosed with schizophrenia, the condition arose before the age of 19.[11] These are critical periods in a young adult's social and vocational development. To minimize the developmental disruption associated with schizophrenia, much work has recently been done to identify and treat the prodromal (pre-onset) phase of the illness, which has been detected up to 30 months before the onset of symptoms, but may be present longer.[12] Those who go on to develop schizophrenia may experience the non-specific symptoms of social withdrawal, irritability and dysphoria in the prodromal period,[13] and transient or self-limiting psychotic symptoms in the prodromal phase before psychosis becomes apparent.[14]

Schneiderian classification

The psychiatrist Kurt Schneider (1887–1967) listed the forms of psychotic symptoms that he thought distinguished schizophrenia from other psychotic disorders. These are called first-rank symptoms or Schneider's first-rank symptoms, and they include delusions of being controlled by an external force; the belief that thoughts are being inserted into or withdrawn from one's conscious mind; the belief that one's thoughts are being broadcast to other people; and hearing hallucinatory voices that comment on one's thoughts or actions or that have a conversation with other hallucinated voices.[15] Although they have significantly contributed to the current diagnostic criteria, the specificity of first-rank symptoms has been questioned. A review of the diagnostic studies conducted between 1970 and 2005 found that these studies allow neither a reconfirmation nor a rejection of Schneider's claims, and suggested that first-rank symptoms be de-emphasized in future revisions of diagnostic systems.[16]

Positive and negative symptoms

Schizophrenia is often described in terms of positive and negative (or deficit) symptoms.[17] The term positive symptoms refers to symptoms that most individuals do not normally experience but are present in schizophrenia. They include delusions, auditory hallucinations, and thought disorder, and are typically regarded as manifestations of psychosis. Negative symptoms are things that are not present in schizophrenic persons but are normally found in healthy persons, that is, symptoms that reflect the loss or absence of normal traits or abilities. Common negative symptoms include flat or blunted affect and emotion, poverty of speech (alogia), inability to experience pleasure (anhedonia), lack of desire to form relationships (asociality), and lack of motivation (avolition). Research suggests that negative symptoms contribute more to poor quality of life, functional disability, and the burden on others than do positive symptoms.[18]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is based on the self-reported experiences of the person, and abnormalities in behavior reported by family members, friends or co-workers, followed by a clinical assessment by a psychiatrist, social worker, clinical psychologist, mental health nurse or other mental health professional. Psychiatric assessment includes a psychiatric history and some form of mental status examination.

Standardized criteria

The most widely used standardized criteria for diagnosing schizophrenia come from the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, version DSM-IV-TR, and the World Health Organization's International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, the ICD-10. The latter criteria are typically used in European countries, while the DSM criteria are used in the United States and the rest of the world, as well as prevailing in research studies. The ICD-10 criteria put more emphasis on Schneiderian first-rank symptoms, although, in practice, agreement between the two systems is high.[19]

According to the revised fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, three diagnostic criteria must be met:[5]

- Characteristic symptoms: Two or more of the following, each present for much of the time during a one-month period (or less, if symptoms remitted with treatment).

- Delusions

- Hallucinations

- Disorganized speech, which is a manifestation of formal thought disorder

- Grossly disorganized behavior (e.g. dressing inappropriately, crying frequently) or catatonic behavior

- Negative symptoms: Blunted affect (lack or decline in emotional response), alogia (lack or decline in speech), or avolition (lack or decline in motivation)

- If the delusions are judged to be bizarre, or hallucinations consist of hearing one voice participating in a running commentary of the patient's actions or of hearing two or more voices conversing with each other, only that symptom is required above. The speech disorganization criterion is only met if it is severe enough to substantially impair communication.

- Social/occupational dysfunction: For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, one or more major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care, are markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset.

- Duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least six months. This six-month period must include at least one month of symptoms (or less, if symptoms remitted with treatment).

If signs of disturbance are present for more than a month but less than six months, the diagnosis of schizophreniform disorder is applied.[5] Psychotic symptoms lasting less than a month may be diagnosed as brief psychotic disorder, and various conditions may be classed as psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. Schizophrenia cannot be diagnosed if symptoms of mood disorder are substantially present (although schizoaffective disorder could be diagnosed), or if symptoms of pervasive developmental disorder are present unless prominent delusions or hallucinations are also present, or if the symptoms are the direct physiological result of a general medical condition or a substance, such as abuse of a drug or medication.

Confusion with other conditions

Psychotic symptoms may be present in several other mental disorders, including bipolar disorder,[20] borderline personality disorder,[21] drug intoxication and drug-induced psychosis. Delusions ("non-bizarre") are also present in delusional disorder, and social withdrawal in social anxiety disorder, avoidant personality disorder and schizotypal personality disorder. Schizophrenia is complicated with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) considerably more often than could be explained by pure chance, although it can be difficult to distinguish compulsions that represent OCD from the delusions of schizophrenia.[22]

A more general medical and neurological examination may be needed to rule out medical illnesses which may rarely produce psychotic schizophrenia-like symptoms,[5] such as metabolic disturbance, systemic infection, syphilis, HIV infection, epilepsy, and brain lesions. It may be necessary to rule out a delirium, which can be distinguished by visual hallucinations, acute onset and fluctuating level of consciousness, and indicates an underlying medical illness. Investigations are not generally repeated for relapse unless there is a specific medical indication or possible adverse effects from antipsychotic medication.

"Schizophrenia" does not mean dissociative identity disorder—formerly and still widely known as "multiple personalities"—despite the etymology of the word (Greek σχίζω = "I split").

Subtypes

The DSM-IV-TR contains five sub-classifications of schizophrenia, although the developers of DSM-5 are recommending they be dropped from the new classification:[23]

- Paranoid type: Where delusions and hallucinations are present but thought disorder, disorganized behavior, and affective flattening are absent. (DSM code 295.3/ICD code F20.0)

- Disorganized type: Named hebephrenic schizophrenia in the ICD. Where thought disorder and flat affect are present together. (DSM code 295.1/ICD code F20.1)

- Catatonic type: The subject may be almost immobile or exhibit agitated, purposeless movement. Symptoms can include catatonic stupor and waxy flexibility. (DSM code 295.2/ICD code F20.2)

- Undifferentiated type: Psychotic symptoms are present but the criteria for paranoid, disorganized, or catatonic types have not been met. (DSM code 295.9/ICD code F20.3)

- Residual type: Where positive symptoms are present at a low intensity only. (DSM code 295.6/ICD code F20.5)

The ICD-10 defines two additional subtypes.

- Post-schizophrenic depression: A depressive episode arising in the aftermath of a schizophrenic illness where some low-level schizophrenic symptoms may still be present. (ICD code F20.4)

- Simple schizophrenia: Insidious and progressive development of prominent negative symptoms with no history of psychotic episodes. (ICD code F20.6)

Controversies and research directions

The scientific validity of schizophrenia, and its defining symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations, have been criticised.[24][25] In 2006, a group of consumers and mental health professionals from the UK, under the banner of Campaign for Abolition of the Schizophrenia Label, argued for a rejection of the diagnosis of schizophrenia based on its heterogeneity and associated stigma, and called for the adoption of a biopsychosocial model. Other UK psychiatrists opposed the move arguing that the term schizophrenia is a useful, even if provisional concept.[26][27]

Similarly, there is an argument that the underlying issues would be better addressed as a spectrum of conditions[28] or as individual dimensions along which everyone varies rather than by a diagnostic category based on an arbitrary cut-off between normal and ill.[29] This approach appears consistent with research on schizotypy, and with a relatively high prevalence of psychotic experiences, mostly non-distressing delusional beliefs, among the general public.[30][31][32] In concordance with this observation, psychologist Edgar Jones, and psychiatrists Tony David and Nassir Ghaemi, surveying the existing literature on delusions, pointed out that the consistency and completeness of the definition of delusion have been found wanting by many; delusions are neither necessarily fixed, nor false, nor involve the presence of incontrovertible evidence.[33][34][35]

Nancy Andreasen, a leading figure in schizophrenia research, has criticized the current DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria for sacrificing diagnostic validity for the sake of artificially improving reliability. She argues that overemphasis on psychosis in the diagnostic criteria, while improving diagnostic reliability, ignores more fundamental cognitive impairments that are harder to assess due to large variations in presentation.[36][37] This view is supported by other psychiatrists.[38] In the same vein, Ming Tsuang and colleagues argue that psychotic symptoms may be a common end-state in a variety of disorders, including schizophrenia, rather than a reflection of the specific etiology of schizophrenia, and warn that there is little basis for regarding DSM’s operational definition as the "true" construct of schizophrenia.[28] Neuropsychologist Michael Foster Green went further in suggesting the presence of specific neurocognitive deficits may be used to construct phenotypes that are alternatives to those that are purely symptom-based. These deficits take the form of a reduction or impairment in basic psychological functions such as memory, attention, executive function and problem solving.[39][40]

The exclusion of affective components from the criteria for schizophrenia, despite their ubiquity in clinical settings, has also caused contention. This exclusion in the DSM has resulted in a "rather convoluted" separate disorder—schizoaffective disorder.[38] Citing poor interrater reliability, some psychiatrists have totally contested the concept of schizoaffective disorder as a separate entity.[41][42] The categorical distinction between mood disorders and schizophrenia, known as the Kraepelinian dichotomy, has also been challenged by data from genetic epidemiology.[43]

An approach broadly known as the anti-psychiatry movement, most active in the 1960s, opposes the orthodox medical view of schizophrenia as an illness.[44] Psychiatrist Thomas Szasz argues that psychiatric patients are individuals with unconventional thoughts and behavior that society diagnoses as a method of social control, and therefore the diagnosis of "schizophrenia" is merely a form of social construction.[45] The Hearing Voices Movement argues that many people diagnosed as psychotic need their experiences to be accepted and valued rather than medicalized.

Causes

While the reliability of the diagnosis introduces difficulties in measuring the relative effect of genes and environment (for example, symptoms overlap to some extent with severe bipolar disorder or major depression), evidence suggests that genetic and environmental factors can act in combination to result in schizophrenia.[47] Evidence suggests that the diagnosis of schizophrenia has a significant heritable component but that onset is significantly influenced by environmental factors or stressors.[48] The idea of an inherent vulnerability (or diathesis) in some people, which can be unmasked by biological, psychological or environmental stressors, is known as the stress-diathesis model.[49] An alternative idea that biological, psychological and social factors are all important is known as the "biopsychosocial" model.

Genetic

Estimates of the heritability of schizophrenia tend to vary owing to the difficulty of separating the effects of genetics and the environment although twin and adoption studies have suggested a high level of heritability (the proportion of variation between individuals in a population that is influenced by genetic factors).[50] It has been suggested that schizophrenia is a condition of complex inheritance, with many different potential genes each of small effect, with different pathways for different individuals. Some have suggested that several genetic and other risk factors need to be present before a person becomes affected but this is still uncertain.[51] Candidate genes linked to an increased risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder as found in recent genome wide association studies appear to be partly separate and partly overlapping between the two disorders[52] Metaanalyses of genetic linkage studies have produced evidence of chromosomal regions increasing susceptibility,[53] which interacts directly with the Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) gene protein[54] more recently the zinc finger protein 804A.[55] has been implicated as well as the chromosome 6 HLA region.[56] However, a large and comprehensive genetic study found no evidence of any significant association with any of 14 previously identified candidate genes.[57] Schizophrenia, in a small minority of cases, has been associated with rare deletions or duplications of tiny DNA sequences (known as copy number variants) disproportionately occurring within genes involved in neuronal signaling and brain development/human cognitive, behavioral, and psychological variation.[58][59][60] Relations have been found between autism and schizophrenia based on duplications and deletions of chromosomes; research showed that schizophrenia and autism are significantly more common in combination with 1q21.1 deletion syndrome, velo-cardio-facial syndrome and Phelan-McDermid syndrome. Duplications of parts of the chrmosomes which are opposites of these syndromes show more autism-results. Research on autism/schizophrenia relations for chromosome 15 (15q13.3), chromosome 16 (16p13.1) and chromosome 17 (17p12) are inconclusive.[61].

Assuming a hereditary genetic basis, one question for evolutionary psychology is why genes that increase the likelihood of the condition evolved, assuming the condition would have been maladaptive from an evolutionary/reproductive point of view. One theory implicates genes involved in the evolution of language and human nature, but so far all theories have been disproved or remain unsubstantiated.[62][63]

Prenatal

Causal factors are thought to initially come together in early neurodevelopment to increase the risk of later developing schizophrenia. One curious finding is that people diagnosed with schizophrenia are more likely to have been born in winter or spring, (at least in the northern hemisphere).[64] There is now evidence that prenatal exposure to infections increases the risk for developing schizophrenia later in life, providing additional evidence for a link between in utero developmental pathology and risk of developing the condition.[65]

Social

Living in an urban environment has been consistently found to be a risk factor for schizophrenia.[66][67] Social disadvantage has been found to be a risk factor, including poverty[68] and migration related to social adversity, racial discrimination, family dysfunction, unemployment or poor housing conditions.[69] Childhood experiences of abuse or trauma have also been implicated as risk factors for a diagnosis of schizophrenia later in life.[70][71] Parenting is not held responsible for schizophrenia but unsupportive dysfunctional relationships may contribute to an increased risk.[72][73]

Substance Abuse

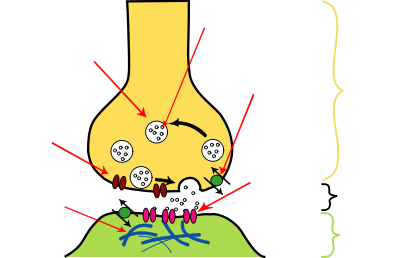

| Structure of a typical chemical synapse |

|---|

Postsynaptic

density Voltage-

gated Ca++ channel Synaptic

vesicle Reuptake

pump Receptor

Axon terminal

|

In a recent study of people with schizophrenia and a substance abuse disorder, over a ten year period, "substantial proportions were above cutoffs selected by dual diagnosis clients as indicators of recovery."[74] Although about half of all patients with schizophrenia use drugs or alcohol, and the vast majority use tobacco, a clear causal connection between drug use and schizophrenia has been difficult to prove. The two most often used explanations for this are "substance use causes schizophrenia" and "substance use is a consequence of schizophrenia", and they both may be correct.[75] A 2007 meta-analysis estimated that cannabis use is statistically associated with a dose-dependent increase in risk of development of psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia, though the authors admit that some uncertainty about causality still remains.[76] For example, cannabis use has increased dramatically in several countries over the past few decades, though contrary to predictions the rates of psychosis and schizophrenia have generally not increased.[77][78][79]

Psychotic individuals may also use drugs to cope with unpleasant states such as depression, anxiety, boredom and loneliness, because drugs increase "feel-good" neurotransmitters level.[80] Various studies have shown that amphetamines increases the concentrations of dopamine in the synaptic cleft, thereby heightening the response of the post-synaptic neuron.[81] However, regarding psychosis itself, it is well understood that methamphetamine and cocaine use can result in methamphetamine- or cocaine-induced psychosis that present very similar symptomatology (sometimes even misdiagnosed as schizophrenia) and may persist even when users remain abstinent.[82] The same can also be said for alcohol-induced psychosis, though to a somewhat lesser extent.[83][84][85]

Mechanisms

Psychological

A number of psychological mechanisms have been implicated in the development and maintenance of schizophrenia. Cognitive biases that have been identified in those with a diagnosis or those at risk, especially when under stress or in confusing situations, include excessive attention to potential threats, jumping to conclusions, making external attributions, impaired reasoning about social situations and mental states, difficulty distinguishing inner speech from speech from an external source, and difficulties with early visual processing and maintaining concentration.[86][87][88][89] Some cognitive features may reflect global neurocognitive deficits in memory, attention, problem-solving, executive function or social cognition, while others may be related to particular issues and experiences.[72][90]

Despite a common appearance of "blunted affect", recent findings indicate that many individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia are emotionally responsive, particularly to stressful or negative stimuli, and that such sensitivity may cause vulnerability to symptoms or to the disorder.[91][91][92][93] Some evidence suggests that the content of delusional beliefs and psychotic experiences can reflect emotional causes of the disorder, and that how a person interprets such experiences can influence symptomatology.[94][95][96][97] The use of "safety behaviors" to avoid imagined threats may contribute to the chronicity of delusions.[98] Further evidence for the role of psychological mechanisms comes from the effects of psychotherapies on symptoms of schizophrenia.[99]

Neural

Studies using neuropsychological tests and brain imaging technologies such as fMRI and PET to examine functional differences in brain activity have shown that differences seem to most commonly occur in the frontal lobes, hippocampus and temporal lobes.[100] These differences have been linked to the neurocognitive deficits often associated with schizophrenia.[101]

Particular focus has been placed upon the function of dopamine in the mesolimbic pathway of the brain. This focus largely resulted from the accidental finding that a drug group which blocks dopamine function, known as the phenothiazines, could reduce psychotic symptoms. It is also supported by the fact that amphetamines, which trigger the release of dopamine, may exacerbate the psychotic symptoms in schizophrenia.[102] An influential theory, known as the Dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, proposed that excess activation of D2 receptors was the cause of (the positive symptoms of) schizophrenia. Although postulated for about 20 years based on the D2 blockade effect common to all antipsychotics, it was not until the mid-1990s that PET and SPET imaging studies provided supporting evidence. This explanation is now thought to be simplistic, partly because newer antipsychotic medication (called atypical antipsychotic medication) can be equally effective as older medication (called typical antipsychotic medication), but also affects serotonin function and may have slightly less of a dopamine blocking effect.[103]

Interest has also focused on the neurotransmitter glutamate and the reduced function of the NMDA glutamate receptor in schizophrenia. This has largely been suggested by abnormally low levels of glutamate receptors found in postmortem brains of people previously diagnosed with schizophrenia[104] and the discovery that the glutamate blocking drugs such as phencyclidine and ketamine can mimic the symptoms and cognitive problems associated with the condition.[105] The fact that reduced glutamate function is linked to poor performance on tests requiring frontal lobe and hippocampal function and that glutamate can affect dopamine function, all of which have been implicated in schizophrenia, have suggested an important mediating (and possibly causal) role of glutamate pathways in schizophrenia.[106] Positive symptoms fail however to respond to glutamatergic medication.[107]

There have also been findings of differences in the size and structure of certain brain areas in schizophrenia. A 2006 metaanlaysis of MRI studies found that whole brain and hippocampal volume are reduced and that ventricular volume is increased in patients with a first psychotic episode relative to healthy controls. The average volumetric changes in these studies are however close to the limit of detection by MRI methods, so it remains to be determined whether schizophrenia is a neurodegenerative process that begins at about the time of symptom onset, or whether it is better characterised as a neurodevelopmental process that produces abnormal brain volumes at an early age.[108] In first episode psychosis typical antipsychotics like haloperidol were associated with significant reductions in gray matter volume, whereas atypical antipsychotics like olanzapine were not.[109] Studies in non-human primates found gray and white matter reductions for both typical and atypical antipsychotics.[110]

A 2009 meta-analysis of diffusion tensor imaging studies identified two consistent locations of reduced fractional anisotropy (roughly the level of organization of neural connections) in schizophrenia. The authors suggest that two networks of white matter tracts may be affected in schizophrenia, with the potential for "disconnection" of the gray matter regions which they link.[111] During fMRI studies, greater connectivity in the brain's default network and task-positive network has been observed in patients diagnosed with schizophrenia, and may reflect excessive attentional orientation toward introspection and toward extrospection, respectively. The greater anti-correlation between the two networks suggests excessive rivalry between the networks.[112]

Screening and prevention

There are no reliable markers for the later development of schizophrenia although research is being conducted into how well a combination of genetic risk plus non-disabling psychosis-like experience predicts later diagnosis.[113] People who fulfill the 'ultra high-risk mental state' criteria, that include a family history of schizophrenia plus the presence of transient or self-limiting psychotic experiences, have a 20–40% chance of being diagnosed with the condition after one year.[114] The use of psychological treatments and medication has been found effective in reducing the chances of people who fulfill the 'high-risk' criteria from developing full-blown schizophrenia.[115] However, the treatment of people who may never develop schizophrenia is controversial,[116] in light of the side-effects of antipsychotic medication; particularly with respect to the potentially disfiguring tardive dyskinesia and the rare but potentially lethal neuroleptic malignant syndrome.[117] The most widely used form of preventative health care for schizophrenia takes the form of public education campaigns that provide information on risk factors and early symptoms, with the aim to improve detection and provide treatment earlier for those experiencing delays.[118] The new clinical approach early intervention in psychosis is a secondary prevention strategy to prevent further episodes and prevent the long term disability associated with schizophrenia.

Management

The concept of a cure as such remains controversial, as there is no consensus on the definition, although some criteria for the remission of symptoms have recently been suggested.[119] The effectiveness of schizophrenia treatment is often assessed using standardized methods, one of the most common being the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS).[120] Management of symptoms and improving function is thought to be more achievable than a cure. Treatment was revolutionized in the mid-1950s with the development and introduction of chlorpromazine.[121] A recovery model is increasingly adopted, emphasizing hope, empowerment and social inclusion.[122]

Hospitalization may occur with severe episodes of schizophrenia. This can be voluntary or (if mental health legislation allows it) involuntary (called civil or involuntary commitment). Long-term inpatient stays are now less common due to deinstitutionalization, although can still occur.[7] Following (or in lieu of) a hospital admission, support services available can include drop-in centers, visits from members of a community mental health team or Assertive Community Treatment team, supported employment[123] and patient-led support groups.

In many non-Western societies, schizophrenia may only be treated with more informal, community-led methods. Multiple international surveys by the World Health Organization over several decades have indicated that the outcome for people diagnosed with schizophrenia in non-Western countries is on average better there than for people in the West.[124] Many clinicians and researchers suspect the relative levels of social connectedness and acceptance are the difference,[125] although further cross-cultural studies are seeking to clarify the findings.

Medication

The first line psychiatric treatment for schizophrenia is antipsychotic medication.[126] These can reduce the positive symptoms of psychosis. Most antipsychotics take around 7–14 days to have their main effect. Currently available antipsychotics fail, however, to significantly ameliorate the negative symptoms, and the improvements on cognition may be attributed to the practice effect.[127][128][129][130]

The newer atypical antipsychotic drugs are usually preferred for initial treatment over the older typical antipsychotic, although they are expensive and are more likely to induce weight gain and obesity-related diseases.[131] In 2005–2006, results from a major randomized trial sponsored by the US National Institute of Mental Health (Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness, or CATIE)[132] found that a representative first-generation antipsychotic, perphenazine, was as effective as and more cost-effective than several newer drugs taken for up to 18 months. The atypical antipsychotic which patients were willing to continue for the longest, olanzapine, was associated with considerable weight gain and risk of metabolic syndrome. Clozapine was most effective for people with a poor response to other drugs, but it had troublesome side effects. Because the trial excluded patients with tardive dyskinesia, its relevance to these people is unclear.[133]

Careful approach needs to be taken when blocking dopamine function, which is responsible for the psychological reward system. Excessive blocking of this neurotransmitter can cause dysphoria. This may cause suicidal ideation, or lead some patients to compensate for their dopamine deficiency with illicit drugs or alcohol. Atypical antipsychotics are preferred for this reason, because they are less likely to cause movement disorders, dysphoria, and increased drug cravings that have been associated with older typical antipsychotics.[134]

Because of their reportedly lower risk of side effects that affect mobility, atypical antipsychotics have been first-line treatment for early-onset schizophrenia for many years before certain drugs in this class were approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in children and teenagers with schizophrenia. This advantage comes at the cost of an increased risk of metabolic syndrome and obesity, which is of concern in the context of long-term use begun at an early age. Especially in the case of children and teenagers who have schizophrenia, medication should be used in combination with individual therapy and family-based interventions.[11]

Recent reviews have refuted the claim that atypical antipsychotics have fewer extrapyramidal side effects than typical antipsychotics, especially when the latter are used in low doses or when low potency antipsychotics are chosen.[135]

Prolactin elevations have been reported in women with schizophrenia taking atypical antipsychotics.[136] It remains unclear whether the newer antipsychotics reduce the chances of developing neuroleptic malignant syndrome, a rare but serious and potentially fatal neurological disorder most often caused by an adverse reaction to neuroleptic or antipsychotic drugs.[137]

Response of symptoms to medication is variable: treatment-resistant schizophrenia is a term used for the failure of symptoms to respond satisfactorily to at least two different antipsychotics.[138] Patients in this category may be prescribed clozapine,[139] a medication of superior effectiveness but several potentially lethal side effects including agranulocytosis and myocarditis.[140] Clozapine may have the additional benefit of reducing propensity for substance abuse in schizophrenic patients.[141] For other patients who are unwilling or unable to take medication regularly, long-acting depot preparations of antipsychotics may be given every two weeks to achieve control. The United States and Australia are two countries with laws allowing the forced administration of this type of medication on those who refuse, but are otherwise stable and living in the community. At least one study suggested that in the longer-term some individuals may do better not taking antipsychotics.[142]

Psychological and social interventions

Psychotherapy is also widely recommended and used in the treatment of schizophrenia, although services may often be confined to pharmacotherapy because of reimbursement problems or lack of training.[143]

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is used to target specific symptoms[144][145][146] and improve related issues such as self-esteem, social functioning, and insight. Although the results of early trials were inconclusive[147] as the therapy advanced from its initial applications in the mid 1990s, some reviews have suggested that CBT is an effective treatment for the psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia.[148][149] However, in a 2010 article in Psychological Medicine entitled, "Cognitive behavioral therapy for the major psychiatric disorder: does it really work?",[150] Lynch, Laws & McKenna found that no trial employing both blinding and psychological placebo has found CBT to be effective in either reducing symptoms or preventing relapse in schizophrenia.

Another approach is cognitive remediation, a technique aimed at remediating the neurocognitive deficits sometimes present in schizophrenia. Based on techniques of neuropsychological rehabilitation, early evidence has shown it to be cognitively effective, with some improvements related to measurable changes in brain activation as measured by fMRI.[151][152] A similar approach known as cognitive enhancement therapy, which focuses on social cognition as well as neurocognition, has shown efficacy.[153]

Family therapy or education, which addresses the whole family system of an individual with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, has been consistently found to be beneficial, at least if the duration of intervention is longer-term.[154][155][156] Aside from therapy, the effect of schizophrenia on families and the burden on carers has been recognized, with the increasing availability of self-help books on the subject.[157][158] There is also some evidence for benefits from social skills training, although there have also been significant negative findings.[159][160] Some studies have explored the possible benefits of music therapy and other creative therapies.[161][162][163]

The Soteria model is alternative to inpatient hospital treatment using a minimal medication approach. It is described as a milieu-therapeutic recovery method, characterized by its founder as "the 24 hour a day application of interpersonal phenomenologic interventions by a nonprofessional staff, usually without neuroleptic drug treatment, in the context of a small, homelike, quiet, supportive, protective, and tolerant social environment."[164] Although research evidence is limited, a 2008 systematic review found the programme equally as effective as treatment with medication in people diagnosed with first and second episode schizophrenia.[165]

Other

Electroconvulsive therapy is not considered a first line treatment but may be prescribed in cases where other treatments have failed. It is more effective where symptoms of catatonia are present,[166] and is recommended for use under NICE guidelines in the UK for catatonia if previously effective, though there is no recommendation for use for schizophrenia otherwise.[167] Psychosurgery has now become a rare procedure and is not a recommended treatment.[168]

Service-user led movements have become integral to the recovery process in Europe and the United States; groups such as the Hearing Voices Network and the Paranoia Network have developed a self-help approach that aims to provide support and assistance outside the traditional medical model adopted by mainstream psychiatry. By avoiding framing personal experience in terms of criteria for mental illness or mental health, they aim to destigmatize the experience and encourage individual responsibility and a positive self-image. Partnerships between hospitals and consumer-run groups are becoming more common, with services working toward remediating social withdrawal, building social skills and reducing rehospitalization.[169]

Regular exercise can have healthful effects on both the physical and mental health and well-being of individuals with schizophrenia.[170]

Prognosis

Course

Coordinated by the World Health Organization and published in 2001, The International Study of Schizophrenia (ISoS) was a long-term follow-up study of 1633 individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia around the world. Of the 75% who were available for follow-up, half had a favourable outcome, and 16% had a delayed recovery after an early unremitting course. More usually, the course in the first two years predicted the long-term course. Early social intervention was also related to a better outcome. The findings were held as important in moving patients, carers and clinicians away from the prevalent belief of the chronic nature of the condition.[171] A review of major longitudinal studies in North America noted this variation in outcomes, although outcome was on average worse than for other psychotic and psychiatric disorders. A moderate number of patients with schizophrenia were seen to remit and remain well; the review raised the question that some may not require maintenance medication.[172]

A clinical study using strict recovery criteria (concurrent remission of positive and negative symptoms and adequate social and vocational functioning continuously for two years) found a recovery rate of 14% within the first five years.[173] A 5-year community study found that 62% showed overall improvement on a composite measure of clinical and functional outcomes.[174]

World Health Organization studies have noted that individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia have much better long-term outcomes in developing countries (India, Colombia and Nigeria) than in developed countries (United States, United Kingdom, Ireland, Denmark, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Japan, and Russia),[175] despite antipsychotic drugs not being widely available.

Defining recovery

Rates are not always comparable across studies because exact definitions of remission and recovery have not been widely established. A "Remission in Schizophrenia Working Group" has proposed standardized remission criteria involving "improvements in core signs and symptoms to the extent that any remaining symptoms are of such low intensity that they no longer interfere significantly with behavior and are below the threshold typically utilized in justifying an initial diagnosis of schizophrenia".[176] Standardized recovery criteria have also been proposed by a number of different researchers, with the stated DSM definitions of a "complete return to premorbid levels of functioning” or "complete return to full functioning" seen as inadequate, impossible to measure, incompatible with the variability in how society defines normal psychosocial functioning, and contributing to self-fulfilling pessimism and stigma.[177] Some mental health professionals may have quite different basic perceptions and concepts of recovery than individuals with the diagnosis, including those in the Consumer/Survivor/Ex-Patient Movement.[178] One notable limitation of nearly all the research criteria is failure to address the person's own evaluations and feelings about their life. Schizophrenia and recovery often involve a continuing loss of self-esteem, alienation from friends and family, interruption of school and career, and social stigma, "experiences that cannot just be reversed or forgotten".[122] An increasingly influential model defines recovery as a process, similar to being "in recovery" from drug and alcohol problems, and emphasizes a personal journey involving factors such as hope, choice, empowerment, social inclusion and achievement.[122]

Predictors

Several factors have been associated with a better overall prognosis: Being female, rapid (vs. insidious) onset of symptoms, older age of first episode, predominantly positive (rather than negative) symptoms, presence of mood symptoms, and good pre-illness functioning.[179][180] The strengths and internal resources of the individual concerned, such as determination or psychological resilience, have also been associated with better prognosis.[172] The attitude and level of support from people in the individual's life can have a significant impact; research framed in terms of the negative aspects of this—the level of critical comments, hostility, and intrusive or controlling attitudes, termed high 'Expressed emotion'—has consistently indicated links to relapse.[181] Most research on predictive factors is correlational in nature, however, and a clear cause-and-effect relationship is often difficult to establish.

Mortality

In a study of over 168,000 Swedish citizens undergoing psychiatric treatment, schizophrenia was associated with an average life expectancy of approximately 80–85% of that of the general population; women were found to have a slightly better life expectancy than men, and a diagnosis of schizophrenia was associated with an overall better life expectancy than substance abuse, personality disorder, heart attack and stroke.[182] Other identified factors include smoking,[183] poor diet, little exercise and the negative health effects of psychiatric drugs.[9]

There is a higher than average suicide rate associated with schizophrenia. This has been cited at 10%, but a more recent analysis of studies and statistics revises the estimate at 4.9%, most often occurring in the period following onset or first hospital admission.[184] Several times more attempt suicide.[185] There are a variety of reasons and risk factors.[186][187]

Violence

The relationship between violent acts and schizophrenia is a contentious topic. Current research indicates that the percentage of people with schizophrenia who commit violent acts is higher than the percentage of people without any disorder, but lower than is found for disorders such as alcoholism, and the difference is reduced or not found in same-neighbourhood comparisons when related factors are taken into account, notably sociodemographic variables and substance misuse.[188] Studies have indicated that 5% to 10% of those charged with murder in Western countries have a schizophrenia spectrum disorder.[189][190][191]

The occurrence of psychosis in schizophrenia has sometimes been linked to a higher risk of violent acts. Findings on the specific role of delusions or hallucinations have been inconsistent, but have focused on delusional jealousy, perception of threat and command hallucinations. It has been proposed that a certain type of individual with schizophrenia may be most likely to offend, characterized by a history of educational difficulties, low IQ, conduct disorder, early-onset substance misuse and offending prior to diagnosis.[189]

Individuals with a diagnosis of schizophrenia are often the victims of violent crime—at least 14 times more often than they are perpetrators.[192][193] Another consistent finding is a link to substance misuse, particularly alcohol,[194] among the minority who commit violent acts. Violence by or against individuals with schizophrenia typically occurs in the context of complex social interactions within a family setting,[195] and is also an issue in clinical services[196] and in the wider community.[197]

Epidemiology

Schizophrenia occurs equally in males and females, although typically appears earlier in men—the peak ages of onset are 20–28 years for males and 26–32 years for females.[2] Onset in childhood is much rarer,[198] as is onset in middle- or old age.[199] The lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia—the proportion of individuals expected to experience the disease at any time in their lives—is commonly given at 1%. However, a 2002 systematic review of many studies found a lifetime prevalence of 0.55%.[4] Despite the received wisdom that schizophrenia occurs at similar rates worldwide, its prevalence varies across the world,[200] within countries,[201] and at the local and neighbourhood level.[202] One particularly stable and replicable finding has been the association between living in an urban environment and schizophrenia diagnosis, even after factors such as drug use, ethnic group and size of social group have been controlled for.[66] Schizophrenia is known to be a major cause of disability. In a 1999 study of 14 countries, active psychosis was ranked the third-most-disabling condition after quadriplegia and dementia and ahead of paraplegia and blindness.[203]

History

Accounts of a schizophrenia-like syndrome are thought to be rare in the historical record before the 1800s, although reports of irrational, unintelligible, or uncontrolled behavior were common. A detailed case report in 1797 concerning James Tilly Matthews, and accounts by Phillipe Pinel published in 1809, are often regarded as the earliest cases of the illness in the medical and psychiatric literature.[204] Schizophrenia was first described as a distinct syndrome affecting teenagers and young adults by Bénédict Morel in 1853, termed démence précoce (literally 'early dementia'). The term dementia praecox was used in 1891 by Arnold Pick to in a case report of a psychotic disorder. In 1893 Emil Kraepelin introduced a broad new distinction in the classification of mental disorders between dementia praecox and mood disorder (termed manic depression and including both unipolar and bipolar depression). Kraepelin believed that dementia praecox was primarily a disease of the brain,[205] and particularly a form of dementia, distinguished from other forms of dementia, such as Alzheimer's disease, which typically occur later in life.[206]

The word schizophrenia—which translates roughly as "splitting of the mind" and comes from the Greek roots schizein (σχίζειν, "to split") and phrēn, phren- (φρήν, φρεν-, "mind")[207]—was coined by Eugen Bleuler in 1908 and was intended to describe the separation of function between personality, thinking, memory, and perception. Bleuler described the main symptoms as 4 A's: flattened Affect, Autism, impaired Association of ideas and Ambivalence.[208] Bleuler realized that the illness was not a dementia as some of his patients improved rather than deteriorated and hence proposed the term schizophrenia instead.

In the early 1970s, the diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia was the subject of a number of controversies which eventually led to the operational criteria used today. It became clear after the 1971 US-UK Diagnostic Study that schizophrenia was diagnosed to a far greater extent in America than in Europe.[209] This was partly due to looser diagnostic criteria in the US, which used the DSM-II manual, contrasting with Europe and its ICD-9. David Rosenhan's 1972 study, published in the journal Science under the title On being sane in insane places, concluded that the diagnosis of schizophrenia in the US was often subjective and unreliable.[210] These were some of the factors in leading to the revision not only of the diagnosis of schizophrenia, but the revision of the whole DSM manual, resulting in the publication of the DSM-III in 1980.{subscription required}[211]

The term schizophrenia is commonly misunderstood to mean that affected persons have a "split personality". Although some people diagnosed with schizophrenia may hear voices and may experience the voices as distinct personalities, schizophrenia does not involve a person changing among distinct multiple personalities. The confusion arises in part due to the literal interpretation of Bleuler's term schizophrenia. The first known misuse of the term to mean "split personality" was in an article by the poet T. S. Eliot in 1933.[212]

Society and culture

Stigma

Social stigma has been identified as a major obstacle in the recovery of patients with schizophrenia.[213] In a large, representative sample from a 1999 study, 12.8% of Americans believed that individuals with schizophrenia were "very likely" to do something violent against others, and 48.1% said that they were "somewhat likely" to. Over 74% said that people with schizophrenia were either "not very able" or "not able at all" to make decisions concerning their treatment, and 70.2% said the same of money management decisions.[214] The perception of individuals with psychosis as violent has more than doubled in prevalence since the 1950s, according to one meta-analysis.[215]

In 2002, the Japanese Society of Psychiatry and Neurology changed the term for schizophrenia from Seishin-Bunretsu-Byo 精神分裂病 (mind-split-disease) to Tōgō-shitchō-shō 統合失調症 (integration disorder) to reduce stigma,[216] The new name was inspired by the biopsychosocial model, and it increased the percentage of cases in which patients were informed of the diagnosis from 36.7% to 69.7% over three years.[217]

Iconic cultural depictions

The book and film A Beautiful Mind chronicled the life of John Forbes Nash, a Nobel Prize-winning mathematician who was diagnosed with schizophrenia. The Marathi film Devrai (featuring Atul Kulkarni) is a presentation of a patient with schizophrenia. The film, set in Western India, shows the behavior, mentality, and struggle of the patient as well as his loved-ones. Other factual books have been written by relatives on family members; Australian journalist Anne Deveson told the story of her son's battle with schizophrenia in Tell Me I'm Here,[218] later made into a movie. The book The Eden Express by Mark Vonnegut recounts his struggle with schizophrenia and his recovering journey.

See also

- Persecutory delusions

- Catastrophic schizophrenia

References

- ↑ "schizophrenia" Concise Medical Dictionary. Oxford University Press, 2010. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Maastricht University Library. 29 June 2010 <http://www.oxfordreference.com/views/ENTRY.html?subview=Main&entry=t60.e9060>

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Castle D, Wessely S, Der G, Murray RM (December 1991). "The incidence of operationally defined schizophrenia in Camberwell, 1965-84". The British Journal of Psychiatry 159: 790–4. doi:10.1192/bjp.159.6.790. PMID 1790446.

- ↑ Bhugra D (May 2005). "The global prevalence of schizophrenia". PLoS Medicine 2 (5): e151; quiz e175. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020151. PMID 15916460.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Goldner EM, Hsu L, Waraich P, Somers JM (November 2002). "Prevalence and incidence studies of schizophrenic disorders: a systematic review of the literature". Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 47 (9): 833–43. PMID 12500753.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 American Psychiatric Association (2000). "Schizophrenia". Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.. ISBN 0-89042-024-6. http://www.behavenet.com/capsules/disorders/schiz.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-04.

- ↑ Rathus, Spencer; Jeffrey Nevid (1991). Abnormal Psychology. Prentice Hall. p. 228. ISBN 0130052167.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Becker T, Kilian R (2006). "Psychiatric services for people with severe mental illness across western Europe: what can be generalized from current knowledge about differences in provision, costs and outcomes of mental health care?". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Supplement 429 (429): 9–16. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00711.x. PMID 16445476.

- ↑ Sim K, Chua TH, Chan YH, Mahendran R, Chong SA (October 2006). "Psychiatric comorbidity in first episode schizophrenia: a 2 year, longitudinal outcome study". Journal of Psychiatric Research 40 (7): 656–63. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.06.008. PMID 16904688.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Brown S, Barraclough B, Inskip H (2000). "Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia". British Journal of Psychiatry 177: 212–7. doi:10.1192/bjp.177.3.212. PMID 11040880.

- ↑ Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM (March 2005). "The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination". Archives of General Psychiatry 62 (3): 247–53. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.247. PMID 15753237.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cullen KR, Kumra S, Regan J et al. (2008). "Atypical Antipsychotics for Treatment of Schizophrenia Spectrum Disorders". Psychiatric Times 25 (3). http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/schizophrenia/article/10168/1147536.

- ↑ Addington J; Cadenhead KS, Cannon TD, Cornblatt B, McGlashan TH, Perkins DO, Seidman LJ, Tsuang M, Walker EF, Woods SW, Heinssen R (2007). "North American prodrome longitudinal study: a collaborative multisite approach to prodromal schizophrenia research". Schizophrenia Bulletin 33 (3): 665–72. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl075. PMID 17255119.

- ↑ Parnas J; Jorgensen A (1989). "Pre-morbid psychopathology in schizophrenia spectrum". British Journal of Psychiatry 115: 623–7. PMID 2611591.

- ↑ Amminger GP; Leicester S, Yung AR, Phillips LJ, Berger GE, Francey SM, Yuen HP, McGorry PD (2006). "Early-onset of symptoms predicts conversion to non-affective psychosis in ultra-high risk individuals". Schizophrenia Research 84 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.018. PMID 16677803.

- ↑ Schneider, K (1959). Clinical Psychopathology (5 ed.). New York: Grune & Stratton. http://books.google.com/?id=ofzOAAAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Nordgaard J, Arnfred SM, Handest P, Parnas J (January 2008). "The diagnostic status of first-rank symptoms". Schizophrenia Bulletin 34 (1): 137–54. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbm044. PMID 17562695.

- ↑ Sims A (2002). Symptoms in the mind: an introduction to descriptive psychopathology. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders. ISBN 0-7020-2627-1.

- ↑ Velligan DI and Alphs LD (March 1, 2008). "Negative Symptoms in Schizophrenia: The Importance of Identification and Treatment". Psychiatric Times 25 (3). http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/schizophrenia/article/10168/1147581.

- ↑ Jakobsen KD; Frederiksen JN, Hansen T, Jansson LB, Parnas J, Werge T (2005). "Reliability of clinical ICD-10 schizophrenia diagnoses". Nordic Journal of Psychiatry 59 (3): 209–12. doi:10.1080/08039480510027698. PMID 16195122.

- ↑ Pope HG (1983). "Distinguishing bipolar disorder from schizophrenia in clinical practice: guidelines and case reports" (PDF). Hospital and Community Psychiatry 34: 322–28. http://psychservices.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/reprint/34/4/322.pdf. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ McGlashan TH (February 1987). "Testing DSM-III symptom criteria for schizotypal and borderline personality disorders". Archives of General Psychiatry 44 (2): 143–8. PMID 3813809.

- ↑ Bottas A (April 15, 2009). "Comorbidity: Schizophrenia With Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder". Psychiatric Times 26 (4). http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/display/article/10168/1402540.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Work Groups (2010) Proposed Revisions - Schizophrenia and Other Psychotic Disorders. Retrieved 17 February 2010.

- ↑ Boyle, Mary (2002). Schizophrenia: a scientific delusion?. New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-22718-6.

- ↑ Bentall, Richard P.; Read, John E; Mosher, Loren R. (2004). Models of Madness: Psychological, Social and Biological Approaches to Schizophrenia. Philadelphia: Brunner-Routledge. ISBN 1-58391-906-6.

- ↑ "Schizophrenia term use 'invalid'". BBC. United Kingdom: BBC News online. 9 October 2006. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/6033013.stm. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ↑ "CASL Biography". http://www.caslcampaign.com/aboutus_biography.php. Retrieved 2009-02-01. and "CASL History". http://www.caslcampaign.com/aboutus.php. Retrieved 2009-02-01.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Tsuang MT; Stone WS, Faraone SV (2000). "Toward reformulating the diagnosis of schizophrenia". American Journal of Psychiatry 157 (7): 1041–50. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.7.1041. PMID 10873908.

- ↑ Peralta V, Cuesta MJ (June 2007). "A dimensional and categorical architecture for the classification of psychotic disorders". World Psychiatry 6 (2): 100–1. PMID 18235866.

- ↑ Verdoux H; van Os J (2002). "Psychotic symptoms in non-clinical populations and the continuum of psychosis". Schizophrenia Research 54 (1–2): 59–65. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00352–8 (inactive 2009-12-08). PMID 11853979.

- ↑ Johns LC; van Os J (2001). "The continuity of psychotic experiences in the general population". Clinical Psychology Review 21 (8): 1125–41. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(01)00103–9 (inactive 2010-03-22). PMID 11702510.

- ↑ Peters ER; Day S, McKenna J, Orbach G (2005). "Measuring delusional ideation: the 21-item Peters et al. Delusions Inventory (PDI)". Schizophrenia Bulletin 30 (4): 1005–22. PMID 15954204.

- ↑ Edgar Jones (1999). "The Phenomenology of Abnormal Belief: A Philosophical and Psychiatric Inquiry". Philosophy, Psychiatry and Psychology 6 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1353/ppp.1999.0004 (inactive 2009-12-08). http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/philosophy_psychiatry_and_psychology/v006/6.1jones01.html. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ David AS (1999). "On the impossibility of defining delusions". Philosophy, Psychiatry and Psychology 6 (1): 17–20. doi:10.1353/ppp.1999.0006 (inactive 2009-12-08). http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/philosophy_psychiatry_and_psychology/v006/6.1david.html. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ S. Nassir Ghaemi (1999). "An Empirical Approach to Understanding Delusions". Philosophy, Psychiatry and Psychology 6 (1): 21–24. doi:10.1353/ppp.1999.0007 (inactive 2009-12-08). http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/philosophy_psychiatry_and_psychology/v006/6.1ghaemi.html. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ Andreasen NC (March 2000). "Schizophrenia: the fundamental questions". Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 31 (2–3): 106–12. doi:10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00027-2. PMID 10719138. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0165017399000272.

- ↑ Andreasen NC (September 1999). "A unitary model of schizophrenia: Bleuler's "fragmented phrene" as schizencephaly". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56 (9): 781–7. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.781. PMID 12884883. http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12884883.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Jansson LB, Parnas J (September 2007). "Competing definitions of schizophrenia: what can be learned from polydiagnostic studies?". Schizophr Bull 33 (5): 1178–200. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl065. PMID 17158508. http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=17158508.

- ↑ Green MF, Nuechterlein KH (1999). "Should schizophrenia be treated as a neurocognitive disorder?". Schizophr Bull 25 (2): 309–19. PMID 10416733. http://schizophreniabulletin.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10416733.

- ↑ Green, Michael (2001). Schizophrenia revealed: from neurons to social interactions. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-70334-7. Lay summary.

- ↑ Lake CR, Hurwitz N (July 2007). "Schizoaffective disorder merges schizophrenia and bipolar disorders as one disease—there is no schizoaffective disorder". Curr Opin Psychiatry 20 (4): 365–79. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e3281a305ab. PMID 17551352. http://meta.wkhealth.com/pt/pt-core/template-journal/lwwgateway/media/landingpage.htm?an=00001504-200707000-00011.

- ↑ Malhi GS, Green M, Fagiolini A, Peselow ED, Kumari V (February 2008). "Schizoaffective disorder: diagnostic issues and future recommendations". Bipolar Disorders 10 (1 Pt 2): 215–30. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2007.00564.x. PMID 18199238.

- ↑ Craddock N, Owen MJ (May 2005). "The beginning of the end for the Kraepelinian dichotomy". Br J Psychiatry 186: 364–6. doi:10.1192/bjp.186.5.364. PMID 15863738. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=15863738.

- ↑ Cooper, David A. (1969). The Dialectics of Liberation (Pelican). London, England: Penguin Books Ltd. ISBN 0-14-021029-6.

- ↑ Szasz, Thomas Stephen (1974). The myth of mental illness: foundations of a theory of personal conduct. San Francisco: Harper & Row. ISBN 0-06-091151-4.

- ↑ Meyer-Lindenberg A; Miletich RS, Kohn PD, Esposito G, Carson RE, Quarantelli M, Weinberger DR, Berman KF (2002). "Reduced prefrontal activity predicts exaggerated striatal dopaminergic function in schizophrenia". Nature Neuroscience 5 (3): 267–71. doi:10.1038/nn804. PMID 11865311.

- ↑ Harrison PJ; Owen MJ (2003). "Genes for schizophrenia? Recent findings and their pathophysiological implications". The Lancet 361 (9355): 417–19. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12379–3 (inactive 2009-12-08). PMID 12573388.

- ↑ Day R; Nielsen JA, Korten A, Ernberg G, Dube KC, Gebhart J, Jablensky A, Leon C, Marsella A, Olatawura M, et al. (1987). "Stressful life events preceding the acute onset of schizophrenia: a cross-national study from the World Health Organization". Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 11 (2): 123–205. doi:10.1007/BF00122563. PMID 3595169.

- ↑ Corcoran C; Walker E, Huot R, Mittal V, Tessner K, Kestler L, Malaspina D (2003). "The stress cascade and schizophrenia: etiology and onset". Schizophrenia Bulletin 29 (4): 671–92. PMID 14989406.

- ↑ O'Donovan MC, Williams NM, Owen MJ (October 2003). "Recent advances in the genetics of schizophrenia". Hum. Mol. Genet. 12 Spec No 2: R125–33. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddg302. PMID 12952866.

- ↑ Owen MJ, Craddock N, O'Donovan MC (September 2005). "Schizophrenia: genes at last?". Trends Genet. 21 (9): 518–25. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2005.06.011. PMID 16009449.

- ↑ Craddock N, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ (January 2006). "Genes for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder? Implications for psychiatric nosology". Schizophr Bull 32 (1): 9–16. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbj033. PMID 16319375.

- ↑ Datta SR, McQuillin A, Rizig M, et al. (June 2010). "A threonine to isoleucine missense mutation in the pericentriolar material 1 gene is strongly associated with schizophrenia". Mol. Psychiatry 15 (6): 615–28. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.128. PMID 19048012.

- ↑ Hennah W, Thomson P, McQuillin A, et al. (September 2009). "DISC1 association, heterogeneity and interplay in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder". Mol. Psychiatry 14 (9): 865–73. doi:10.1038/mp.2008.22. PMID 18317464.

- ↑ O'Donovan MC, Craddock NJ, Owen MJ (July 2009). "Genetics of psychosis; insights from views across the genome". Hum. Genet. 126 (1): 3–12. doi:10.1007/s00439-009-0703-0. PMID 19521722.

- ↑ Purcell SM, Wray NR, Stone JL, et al. (August 2009). "Common polygenic variation contributes to risk of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder". Nature 460 (7256): 748–52. doi:10.1038/nature08185. PMID 19571811.

- ↑ Sanders AR, Duan J, Levinson DF, et al. (April 2008). "No significant association of 14 candidate genes with schizophrenia in a large European ancestry sample: implications for psychiatric genetics". Am J Psychiatry 165 (4): 497–506. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101573. PMID 18198266.

- ↑ Walsh T, McClellan JM, McCarthy SE et al. (2008). "Rare structural variants disrupt multiple genes in neurodevelopmental pathways in schizophrenia". Science 320 (5875): 539–43. doi:10.1126/science.1155174. PMID 18369103.

- ↑ Kirov G, Grozeva D, Norton N et al. (2009). "Support for the involvement of large CNVs in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia". Hum Mol Genet 18 (8): 1497. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp043. PMID 19181681.

- ↑ The International Schizophrenia Consortium (11 September 2008). "Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications increase risk of schizophrenia". Nature 455 (7210): 237–41. doi:10.1038/nature07239. PMID 18668038.

- ↑ Crespi B, Stead P, Elliot M (January 2010). "Evolution in health and medicine Sackler colloquium: Comparative genomics of autism and schizophrenia". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107 Suppl 1: 1736–41. doi:10.1073/pnas.0906080106. PMID 19955444.

- ↑ Crow TJ (July 2008). "The 'big bang' theory of the origin of psychosis and the faculty of language". Schizophr. Res. 102 (1–3): 31–52. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.03.010. PMID 18502103. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0920-9964(08)00149–7.

- ↑ Mueser KT, Jeste DV (2008). Clinical Handbook of Schizophrenia. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 1593856520.

- ↑ Davies G; Welham J, Chant D, Torrey EF, McGrath J (2003). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of Northern Hemisphere season of birth studies in schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin 29 (3): 587–93. PMID 14609251.

- ↑ Brown AS (2006). "Prenatal infection as a risk factor for schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Bulletin 32 (2): 200–2. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbj052. PMID 16469941.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Van Os J (2004). "Does the urban environment cause psychosis?". British Journal of Psychiatry 184 (4): 287–288. doi:10.1192/bjp.184.4.287. PMID 15056569.

- ↑ van Os J, Krabbendam L, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P (March 2005). "The schizophrenia envirome". Current Opinion in Psychiatry 18 (2): 141–5. doi:10.1097/00001504-200503000-00006. PMID 16639166. http://www.co-psychiatry.com/pt/re/copsych/abstract.00001504-200503000-00006.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ↑ Mueser KT, McGurk SR (2004). "Schizophrenia". The Lancet 363 (9426): 2063–72. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16458–1 (inactive 2009-12-08). PMID 15207959.

- ↑ Selten JP, Cantor-Graae E, Kahn RS (March 2007). "Migration and schizophrenia". Current Opinion in Psychiatry 20 (2): 111–115. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328017f68e. PMID 17278906. http://www.co-psychiatry.com/pt/re/copsych/abstract.00001504-200703000-00003.htm. Retrieved 2008-07-06.

- ↑ Schenkel LS; Spaulding WD, Dilillo D, Silverstein SM (2005). "Histories of childhood maltreatment in schizophrenia: Relationships with premorbid functioning, symptomatology, and cognitive deficits". Schizophrenia Research 76 (2–3): 273–286. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.03.003. PMID 15949659.

- ↑ Janssen; Krabbendam L, Bak M, Hanssen M, Vollebergh W, de Graaf R, van Os J (2004). "Childhood abuse as a risk factor for psychotic experiences". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 109 (1): 38–45. doi:10.1046/j.0001–690X.2003.00217.x (inactive 2009-12-08). PMID 14674957.

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Bentall RP; Fernyhough C, Morrison AP, Lewis S, Corcoran R (2007). "Prospects for a cognitive-developmental account of psychotic experiences". Br J Clin Psychol 46 (Pt 2): 155–73. doi:10.1348/014466506X123011. PMID 17524210.

- ↑ Subotnik, KL; Goldstein, MJ, Nuechterlein, KH, Woo, SM and Mintz, J (2002). "Are Communication Deviance and Expressed Emotion Related to Family History of Psychiatric Disorders in Schizophrenia?". Schizophrenia Bulletin 28 (4): 719–29. PMID 12795501.

- ↑ Ten-Year Recovery Outcomes for Clients With Co-Occurring Schizophrenia and Substance Use Disorders - Drake et al. 32 (3): 464 - Schizophrenia Bulletin

- ↑ Ferdinand RF, Sondeijker F, van der Ende J, Selten JP, Huizink A, Verhulst FC (2005). "Cannabis use predicts future psychotic symptoms, and vice versa". Addiction 100 (5): 612–8. doi:10.1111/j.1360–0443.2005.01070.x (inactive 2009-12-08). PMID 15847618.

- ↑ Moore THM, Zammit S, Lingford-Hughes A et al. (2007). "Cannabis use and risk of psychotic or affective mental health outcomes: a systematic review". Lancet 370 (9584): 319–328. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61162-3. PMID 17662880.

- ↑ Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M (2001) (PDF). Comorbidity between cannabis use and psychosis: Modelling some possible relationships.. Technical Report No. 121.. Sydney: National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre.. http://ndarc.med.unsw.edu.au/NDARCWeb.nsf/resources/TR_18/$file/TR.121.PDF. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ Frisher M, Crome I, Martino O, Croft P (September 2009). "Assessing the impact of cannabis use on trends in diagnosed schizophrenia in the United Kingdom from 1996 to 2005". Schizophr. Res. 113 (2-3): 123–8. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2009.05.031. PMID 19560900.

- ↑ http://www.nhsconfed.org/Publications/Documents/MHN_factsheet_August_2009_FINAL_2.pdf Key facts and trends in mental health, National Health Service, 2009

- ↑ Gregg L, Barrowclough C, Haddock G (2007). "Reasons for increased substance use in psychosis". Clin Psychol Rev 27 (4): 494–510. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.004. PMID 17240501.

- ↑ Kuczenski R, Segal DS (May 1997). "Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine: comparison with amphetamine". J. Neurochem. 68 (5): 2032–7. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68052032.x (inactive 2008-12-29). PMID 9109529.

- ↑ Mahoney JJ, Kalechstein AD, De La Garza R, Newton TF (2008). "Presence and persistence of psychotic symptoms in cocaine- versus methamphetamine-dependent participants". The American Journal on Addictions 17 (2): 83–98. doi:10.1080/10550490701861201. PMID 18393050.

- ↑ Larson, Michael (2006-03-30). "Alcohol-Related Psychosis". eMedicine. WebMD. http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic3113.htm. Retrieved September 27, 2006.

- ↑ Soyka, Michael (March 1990). "Psychopathological characteristics in alcohol hallucinosis and paranoid schizophrenia". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 81 (3): 255–9. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.1990.tb06491.x. PMID 2343749.

- ↑ Gossman, William (November 19, 2005). "Delirium Tremens". eMedicine. WebMD. http://www.emedicine.com/EMERG/topic123.htm. Retrieved October 16, 2006.

- ↑ Broome MR, Woolley JB, Tabraham P, et al. (November 2005). "What causes the onset of psychosis?". Schizophr. Res. 79 (1): 23–34. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.007. PMID 16198238.

- ↑ Lewis R (2004). "Should cognitive deficit be a diagnostic criterion for schizophrenia?". Journal of Psychiatry and Neuroscience 29 (2): 102–113. PMID 15069464.

- ↑ Brüne M, Abdel-Hamid M, Lehmkämper C, Sonntag C (May 2007). "Mental state attribution, neurocognitive functioning, and psychopathology: what predicts poor social competence in schizophrenia best?". Schizophr. Res. 92 (1-3): 151–9. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2007.01.006. PMID 17346931.

- ↑ Sitskoorn MM; Aleman A, Ebisch SJH, Appels MCM, Khan RS (2004). "Cognitive deficits in relatives of patients with schizophrenia: a meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Research 71 (2): 285–295. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.03.007. PMID 15474899.

- ↑ Kurtz MM (2005). "Neurocognitive impairment across the lifespan in schizophrenia: an update". Schizophrenia Research 74 (1): 15–26. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.07.005. PMID 15694750.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Cohen AS; Docherty, NM; Docherty NM (2004). "Affective reactivity of speech and emotional experience in patients with schizophrenia". Schizophrenia Research 69 (1): 7–14. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00069–0 (inactive 2009-12-08). PMID 15145465.

- ↑ Horan WP; Blanchard JJ (2003). "Emotional responses to psychosocial stress in schizophrenia: the role of individual differences in affective traits and coping". Schizophrenia Research 60 (2–3): 271–83. doi:10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00227-X. PMID 12591589.

- ↑ Barrowclough C; Tarrier N, Humphreys L, Ward J, Gregg L, Andrews B (2003). "Self-esteem in schizophrenia: relationships between self-evaluation, family attitudes, and symptomatology". J Abnorm Psychol 112 (1): 92–9. doi:10.1037/0021–843X.112.1.92 (inactive 2009-12-08). PMID 12653417.

- ↑ Birchwood M; Meaden A, Trower P, Gilbert P, Plaistow J (2000). "The power and omnipotence of voices: subordination and entrapment by voices and significant others". Psychol Med 30 (2): 337–44. doi:10.1017/S0033291799001828. PMID 10824654.

- ↑ Smith B, Fowler DG, Freeman D, et al. (September 2006). "Emotion and psychosis: links between depression, self-esteem, negative schematic beliefs and delusions and hallucinations". Schizophr. Res. 86 (1-3): 181–8. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2006.06.018. PMID 16857346.

- ↑ Beck, AT (2004). "A Cognitive Model of Schizophrenia". Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy 18 (3): 281–88. doi:10.1891/jcop.18.3.281.65649.

- ↑ Bell V; Halligan PW, Ellis HD (2006). "Explaining delusions: a cognitive perspective". Trends in Cognitive Science 10 (5): 219–26. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2006.03.004. PMID 16600666.

- ↑ Freeman D, Garety PA, Kuipers E, Fowler D, Bebbington PE, Dunn G (January 2007). "Acting on persecutory delusions: the importance of safety seeking". Behav Res Ther 45 (1): 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.014. PMID 16530161.

- ↑ Kuipers E, Garety P, Fowler D, Freeman D, Dunn G, Bebbington P (October 2006). "Cognitive, emotional, and social processes in psychosis: refining cognitive behavioral therapy for persistent positive symptoms". Schizophr Bull 32 Suppl 1: S24–31. doi:10.1093/schbul/sbl014. PMID 16885206.

- ↑ Kircher, Tilo; Renate Thienel (2006). "Functional brain imaging of symptoms and cognition in schizophrenia". The Boundaries of Consciousness. Amsterdam: Elsevier. p. 302. ISBN 0444528768. http://books.google.com/?id=YHGacGKyVbYC&pg=PA302.

- ↑ Green MF (2006). "Cognitive impairment and functional outcome in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder". Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 67 (Suppl 9): 3–8. PMID 16965182.

- ↑ {{cite journal |author=Laruelle M, Abi-Dargham A, van Dyck CH, et al. |title=Single photon emission computerized tomography imaging of amphetamine-induced dopamine release in drug-free schizophrenic subjects |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=93 |issue=17 |pages=9235–40 |year=1996 |month=August |pmid=8799184 |pmc=38625 |doi= 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9235

- ↑ Jones HM; Pilowsky LS (2002). "Dopamine and antipsychotic drug action revisited". British Journal of Psychiatry 181: 271–275. doi:10.1192/bjp.181.4.271. PMID 12356650.

- ↑ Konradi C; Heckers S (2003). "Molecular aspects of glutamate dysregulation: implications for schizophrenia and its treatment". Pharmacology and Therapeutics 97 (2): 153–79. doi:10.1016/S0163-7258(02)00328–5 (inactive 2009-12-08). PMID 12559388.

- ↑ Lahti AC; Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA (2001). "Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers". Neuropsychopharmacology 25 (4): 455–67. doi:10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00243–3 (inactive 2009-12-08). PMID 11557159.

- ↑ Coyle JT; Tsai G, Goff D (2003). "Converging evidence of NMDA receptor hypofunction in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1003: 318–27. doi:10.1196/annals.1300.020. PMID 14684455.

- ↑ Tuominen HJ; Tiihonen J, Wahlbeck K (2005). "Glutamatergic drugs for schizophrenia: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Schizophrenia Research 72 (2-3): 225–34. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2004.05.005. PMID 15560967.

- ↑ Steen RG, Mull C, McClure R, Hamer RM, Lieberman JA (June 2006). "Brain volume in first-episode schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies". Br J Psychiatry 188: 510–8. doi:10.1192/bjp.188.6.510. PMID 16738340. http://bjp.rcpsych.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=16738340.

- ↑ Lieberman JA, Bymaster FP, Meltzer HY, et al. (September 2008). "Antipsychotic drugs: comparison in animal models of efficacy, neurotransmitter regulation, and neuroprotection". Pharmacol. Rev. 60 (3): 358–403. doi:10.1124/pr.107.00107. PMID 18922967.