Saxons

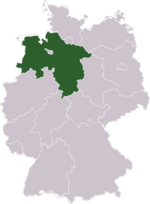

The Saxons (Latin: Saxones) were a confederation of Old Germanic tribes. Their modern-day descendants in Lower Saxony and Westphalia and other German states are considered ethnic Germans (the state of Sachsen is not inhabited by ethnic Saxons; the state of Sachsen-Anhalt is, though, in its northern and western parts); those in the eastern Netherlands are considered to be ethnic Dutch; and those in Southern England ethnic English (see Anglo-Saxons). Their earliest known area of settlement is Northern Albingia, an area approximately that of modern Holstein.

Saxons participated in the Germanic settlement of Britain during and after the 5th century. It is unknown how many migrated from the continent to Britain though estimates for the total number of Germanic settlers vary between 10,000 and 200,000.[1] Since the 18th century, many continental Saxons have settled other parts of the world, especially in North America, Australia, South Africa, South of Brazil and in areas of the former Soviet Union, where some communities still maintain parts of their cultural and linguistic heritage, often under the umbrella categories "German", and "Dutch".

Because of international Hanseatic trading routes and contingent migration during the Middle Ages, Saxons mixed with and had strong influences upon the languages and cultures of the Scandinavian and Baltic peoples, and also upon the Polabian Slavs and Pomeranian West Slavic peoples.

The pre-Christian settlement of the Saxon people originally covered an area a little more to the northwest, with parts of the southern Jutland Peninsula, Old Saxony and small sections of the eastern Low Countries (Belgium and the Netherlands). During the 5th century AD, the Saxons were part of the people invading the Romano-British province of Britannia. One of the other tribes was the Germanic Angles, whose name, taken together with that of the Saxons led to the formation of the modern term, Anglo-Saxons.

Contents |

Early history

Ptolemy's Geographia, written in the 2nd century, is sometimes considered to contain the first mentioning of the Saxons. Some copies of this text mention a tribe called Saxones in the area to the north of the lower River Elbe, thought to derive from the word Sax or stone knife.[2] However, other copies call the same tribe Axones, and it is considered likely that it is a misspelling of the tribe that Tacitus in his Germania called Aviones. It is considered likely that "Saxones" was an attempt by later scribes to correct a name which meant nothing to them.[3]

The first undisputed mention of the Saxon name in its modern form is from 356, when Julian, later the Roman Emperor, mentioned them in a speech as allies of Magnentius, a rival emperor in Gaul. All mentions of the Saxons during the 4th and early 5th centuries referred to pirates and warlords in Gaul and Britain, rather than to a specific tribe or inhabitants of a specific area. In order to defend against Saxon raiders, the Romans created a military district called the Litus Saxonicum ("Saxon Coast") on both sides of the English Channel. In 441/442, Saxons are mentioned for the first time as inhabitants of Britain, when an unknown Gaulish historian wrote: "Britain falls under the rule of the Saxons".

Saxons as inhabitants of present-day Northern Germany are first mentioned in 555, when Theudebald, the Frankish king, died and the Saxons used this opportunity for an uprising. The uprising was suppressed by Chlothar I, Theudebald's successor. Some of their Frankish successors fought against the Saxons, others were allied with them; Chlothar II won a decisive victory against the Saxons. The Thuringians frequently appeared as allies of the Saxons.

The Saxons may have derived their name from seax, a kind of knife for which they were known.[4] The seax has a lasting symbolic impact in the English counties of Essex and Middlesex, both of which feature three seaxes in their ceremonial emblem.

Continental Saxons

Saxony

The Continental Saxons living in what was known as Old Saxony appear to have consolidated themselves by the end of the 8th century. After subjugation by the Emperor Charlemagne a political entity called the Duchy of Saxony appeared.

The Saxons long resisted both becoming Christians[5] and being incorporated into the orbit of the Frankish kingdom, but they were decisively conquered by Charlemagne in a long series of annual campaigns, the Saxon Wars (772 – 804). During Charlemagne's campaign in Hispania (778), the Saxons advanced to Deutz on the Rhine and plundered along the river. With defeat came the enforced baptism and conversion of the Saxon leaders and their people. Their sacred tree or pillar, a symbol of Irminsul, was destroyed.

Under Carolingian rule, the Saxons were reduced to tributary status. There is evidence that the Saxons, as well as Slavic tributaries such as the Abodrites and the Wends, often provided troops to their Carolingian overlords. The dukes of Saxony became kings (Henry I, the Fowler, 919) and later the first emperors (Henry's son, Otto I, the Great) of Germany during the 10th century, but they lost this position in 1024. The duchy was divided up in 1180 when Duke Henry the Lion, Emperor Otto's grandson, refused to follow his cousin, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa, into war in Lombardy.

During the High Middle Ages, under the Salian emperors and, later, under the Teutonic Knights, German settlers moved east along the River Elbe into the area of a western Slavic tribe, the Sorbs. The Sorbs were gradually Germanised. This region subsequently acquired the name Saxony through political circumstances, though it was initially called the March of Meissen. The rulers of Meissen acquired control of the Duchy of Saxony in 1423 and eventually applied the name Saxony to the whole of their kingdom. Since then, this part of eastern Germany has been referred to as Saxony (German: Sachsen), a source of some misunderstanding about the original homeland of the Saxons, mostly in the present-day German state of Lower Saxony (German: Niedersachsen).

Italy and Gaul

In 569, some Saxons accompanied the Lombards into Italy under the leadership of Alboin and settled there.[6] In 572, they raided Gaul as far as Stablo near Riez. Divided, they were easily defeated by Gallo-Roman General Mummolus. When the Saxons regrouped, a peace treaty was negotiated whereby the Italian Saxons were allowed to settle with their families in Austrasia.[7] Gathering their families and belongings in Italy, they returned to Gaul in two groups in 573. One group proceeded by way of Nice and another via Embrun, joining up at Avignon, where they plundered the territory and were consequently stopped from crossing the Rhone by Mummolus. They were forced to pay compensation for what they had robbed before they could enter Austrasia.

Some Saxons already lived in Gaul (e.g. Vron-Ponthieu, Sassetot-le-Mauconduit; Flanders up to Ile d'Aix) at that time. A Saxon king named Eadwacer conquered Angers in 463 only to be dislodged by Childeric I and the Salian Franks, allies of the Roman Empire. It is possible that Saxon settlement of Great Britain began only in response to expanding Frankish control of the Channel coast.[8]

A Saxon unit of laeti had been settled at Bayeux — the Saxones Baiocassenses — since the time of the Notitia Dignitatum.[9] These Saxons became subjects of Clovis I late in the fifth century. The Saxons of Bayeux comprised a standing army and were often called upon to serve alongside the local levy of their region in Merovingian military campaigns. They were ineffective against Waroch in this capacity in 579.[10] In 589, the Saxons wore their hair in the Breton fashion at the orders of Fredegund and fought with them as allies against Guntram.[11] Beginning in 626, the Saxons of the Bessin were used by Dagobert I for his campaigns against the Basques. One of their own, Aeghyna, was even created a dux over the region of Vasconia.[12]

Saxons in Britain

Saxons, along with Angles, Jutes, Frisians, and possibly Franks, invaded or migrated to the island of Great Britain (Britannia) around the time of the collapse of Roman authority in the west. Saxon raiders had been harassing the eastern and southern shores of Britannia for centuries before, prompting the construction of a string of coastal forts called the litora Saxonica or Saxon Shore, and many Saxons and other folk had been permitted to settle in these areas as farmers long before the end of Roman rule in Britannia. According to tradition, however, the Saxons (and other tribes) first entered Britain en masse as part of a deal to protect the Britons from the incursions of the Picts, Irish, and others. The story as reported in such sources as the Historia Brittonum indicates that the British king Vortigern allowed the Germanic warlords Hengist and Horsa to settle their people on the Isle of Thanet in exchange for their service as mercenaries. Hengist manipulated Vortigern into granting more land and allowing for more settlers to come in, paving the way for the Germanic settlement of Britain.

Four separate Saxon realms emerged:

- East Saxons: created the Kingdom of Essex.

- Middle Saxons: created the province of Middlesex

- South Saxons: led by Aelle, created the Kingdom of Sussex

- West Saxons: created the Kingdom of Wessex

During the period of the reigns from Egbert to Alfred the Great, the kings of Wessex emerged as Bretwalda, unifying the country and eventually forging it into the kingdom of England in the face of Viking invasions.

Historians are divided about what followed: some argue that the takeover of southern Great Britain by the Anglo-Saxons was peaceful. There is, however, only one known account from a native Briton who lived at this time (Gildas), and his description is of a forced takeover:

For the fire...spread from sea to sea, fed by the hands of our foes in the east, and did not cease, until, destroying the neighbouring towns and lands, it reached the other side of the island, and dipped its red and savage tongue in the western ocean. In these assaults...all the columns were levelled with the ground by the frequent strokes of the battering-ram, all the husbandmen routed, together with their bishops, priests, and people, whilst the sword gleamed, and the flames crackled around them on every side. Lamentable to behold, in the midst of the streets lay the tops of lofty towers, tumbled to the ground, stones of high walls, holy altars, fragments of human bodies, covered with livid clots of coagulated blood, looking as if they had been squeezed together in a press; and with no chance of being buried, save in the ruins of the houses, or in the ravening bellies of wild beasts and birds; with reverence be it spoken for their blessed souls, if, indeed, there were many found who were carried, at that time, into the high heaven by the holy angels... Some, therefore, of the miserable remnant, being taken in the mountains, were murdered in great numbers; others, constrained by famine, came and yielded themselves to be slaves for ever to their foes, running the risk of being instantly slain, which truly was the greatest favour that could be offered them: some others passed beyond the seas with loud lamentations instead of the voice of exhortation...Others, committing the safeguard of their lives, which were in continual jeopardy, to the mountains, precipices, thickly wooded forests, and to the rocks of the seas (albeit with trembling hearts), remained still in their country.

Social structure

Bede, a Northumbrian, writing around the year 730, remarks that "the old (that is, the continental) Saxons have no king, but they are governed by several ealdormen (or satrapa) who, during war, cast lots for leadership but who, in time of peace, are equal in power." The regnum Saxonum was divided into three provinces — Westphalia, Eastphalia and Angria — which comprised about one hundred pagi or Gaue. Each Gau had its own satrap with enough military power to level whole villages which opposed him.[13]

In the mid 9th century, Nithard first described the social structure of the Saxons beneath their leaders. The caste structure was rigid; in the Saxon language the three castes, excluding slaves, were called the edhilingui (related to the term aetheling), frilingi, and lazzi. These terms were subsequently Latinised as nobiles or nobiliores; ingenui, ingenuiles, or liberi; and liberti, liti, or serviles.[14] According to very early traditions which probably contain a good deal of historical truth, the edhilingui were the descendants of the Saxons who led the tribe out of Holstein and during the migrations of the sixth century.[14] They were a conquering, warrior elite. The frilingi represented the descendants of the amicii, auxiliarii, and manumissi of that caste, while the lazzi represented the descendants of the original inhabitants of the conquered territories, who were forced to make oaths of submission and pay tribute to the edhilingui.

The Lex Saxonum regulated the Saxons' unusual society. Intermarriage between the castes was forbidden by the Lex and wergilds were set based upon caste membership. The edhilingui were worth 1,440 solidi, or about 700 head of cattle, the highest wergild on the continent; the price of a bride was also very high. This was six times as much as that of the frilingi and eight times as much as the lazzi. The gulf between noble and ignoble was very large, but the difference between a freeman and an indentured labourer was small.[15]

According to the Vita Lebuini antiqua, an important source for early Saxon history, the Saxons held an annual council at Marklo where they "confirmed their laws, gave judgment on outstanding cases, and determined by common counsel whether they would go to war or be in peace that year."[13] All three castes participated in the general council; twelve representatives from each caste were sent from each Gau. In 782, Charlemagne abolished the system of Gaue and replaced it with the Grafschaftsverfassung, the system of counties typical of Francia.[16] Charlemagne outlawed the Marklo councils and thus pushed the frilingi and lazzi out of political power. The old Saxon system of Abgabengrundherrschaft, lordship based on dues and taxes, was replaced by a form of feudalism based on service and labour, personal relationships, and oaths.[17]

Religion

Paganism and politics

Saxon pagan practices were closely related to Saxon political practices. The annual councils of the entire tribe began with invocations of the gods, and the procedure by which dukes were elected in wartime, by drawing lots, probably had pagan significance, that is, giving trust to divine providence to guide the seemingly random decision making.[18] There were also sacred rituals and objects, such as the pillars called Irminsul, which were believed to connect heaven and earth. Charlemagne had one such pillar chopped down in 772.

Something of pagan Saxon practice in Britain can be gleaned from place names. The Germanic gods Woden, Frigg, Tiw, and Thunor, who are attested to in every Germanic pagan tradition, were worshipped in Wessex, Sussex, and Essex, and they are the only ones directly attested to, though the names of the third and fourth months (March and April) of the Old English calendar bear the names Hrethmonath and Eosturmonath, meaning "month of Hretha" and "month of Ēostre", apparently from the names of two goddesses who were worshipped around that season.[19] The pagan Saxons offered cakes to their gods in February (Solmonath) and there was a religious festival associated with the harvest, Halegmonath ("holy month" or month of offerings", September).[20] The pagan calendar began on 25 December, and the months of December and January were called Yule (or Giuli) and contained a Modra niht or "night of the mothers", another religious festival of unknown content.

The Saxon freemen and servile class remained practising pagans long after their nominal conversion to Christianity. Nursing a hatred of the upper class which, with Frankish assistance, had marginalised them from political power, the lower classes (the plebeium vulgus or cives) were still a problem for Christian authorities as late as 836, when the Translatio S. Liborii remarks on their obstinacy in pagan ritus et superstitio (usage and superstition).[21]

Conversion and resistance

The conversion of the Saxons in England from their original Germanic paganism to Christianity occurred in the early to late seventh century under the influence of the already converted Jutes of Kent. In the 630s, Birinus became the "apostle to the West Saxons" and converted Wessex, whose first Christian king was Cynegils. The West Saxons begin to emerge from obscurity only with their conversion to Christianity and the keeping of written records. The Gewisse, a West Saxon people, were especially resistant to Christianity; but Birinus merely exercised more efforts against them.[19] In Wessex, a bishopric was founded at Dorchester. The South Saxons were first evangelised extensively under Anglian influence; Aethelwalh of Sussex was converted by Wulfhere, King of Mercia, and allowed Wilfrid, Archbishop of York, to evangelise his people beginning in 681. The chief South Saxon bishopric was that of Selsey. The East Saxons were more pagan than the southern or western Saxons; their territory had a superabundance of pagan sites.[22] Their king, Saeberht, was converted early and a diocese was established at London, but its first bishop, Mellitus, was expelled by Saeberth's heirs. The conversion of the East Saxons was only completed under Cedd in the 650s and 660s.

The continental Saxons were evangelised largely by English missionaries in the late seventh and early eighth centuries. Around 695, two early English missionaries, Hewald the White and Hewald the Black were martyred by the vicani, that is, villagers.[18] Throughout the century that followed, it was the villagers and other peasants who were to prove the greatest opponents of Christianisation, while missionaries often received the support of the edhilingui and other noblemen. Saint Lebuin, an Englishman who preached to the Saxons between 745 and 770, built a church and made many friends among the nobility, some of whom were compelled to save him from an angry mob at the annual council at Marklo. Social tensions arose between the Christianity-sympathetic noblemen and the staunchly pagan lower castes.[23]

Under Charlemagne, the Saxon Wars had as their chief object the conversion and integration of the Saxons into the Frankish empire. Though much of the highest caste converted readily, forced baptisms and forced tithing made enemies of the lower orders. Even some contemporaries found the methods employed to win over the Saxons wanting, as this excerpt from a letter of Alcuin of York to his friend Meginfrid, written in 796, shows:

If the light yoke and sweet burden of Christ were to be preached to the most obstinate people of the Saxons with as much determination as the payment of tithes has been exacted, or as the force of the legal decree has been applied for fault of the most trifling sort imaginable, perhaps they would not be averse to their baptismal vows.[24]

Louis the Pious, Charlemagne's successor, reportedly treated the Saxons more as Alcuin would have wished, and consequently they were faithful subjects.[25] The lower classes, however, revolted against Frankish overlordship in favour of their old paganism as late as the 840s, when the Stellinga rose up against the Saxon leadership, who were allied with the Frankish emperor Lothair I. After the suppression of the Stellinga, in 851 Louis the German brought relics from Rome to Saxony to foster a devotion to the Roman Catholic Church.[26] When the Poeta Saxo composed his verse Annales of Charlemagne's reign with an emphasis on his conquest of Saxony, the great emperor was viewed on par with the Roman emperors as the bringer of Christian salvation to a pagan people.

Vernacular Christianity

In the ninth century, the Saxon nobility became vigorous supporters of monasticism and formed a bulwark of Christianity against the existing Slavic paganism to the east and the Nordic paganism of the Vikings to the north. Indeed, Saxony, once so pagan, became the source of a bold and unique Christianity, as evidenced by the Christian literature in the vernacular Old Saxon; the literary output and wide influence of Saxon monasteries such as Fulda, Corvey, and Verden; and the theological controversy between the Augustinian Gottschalk and the semipelagian Rabanus Maurus.[27]

From an early date, Charlemagne and Louis the Pious supported Christian vernacular works in order to evangelise the Saxons more efficiently. The Heiland, a verse epic of the life of Christ in a Germanic setting, and Genesis, another epic retelling of the events of the first book of the Bible, were commissioned in the early ninth century by Louis to disseminate scriptural knowledge to the masses. A council of Tours in 813 and then a synod of Mainz in 848 both declared that homilies ought to be preached in the vernacular. The earliest preserved text in the Saxon language is a baptismal vow from the late eighth or early ninth century; the vernacular was used extensively in an effort to Christianise the lowest castes of Saxon society.[28]

Etymology

Following the downfall of Henry the Lion and the subsequent split of the Saxon tribal duchy into several territories, the name of the Saxon duchy was transferred to the lands of the Ascanian family. This led to the differentiation between Lower Saxony, lands settled by the Saxon tribe, and Upper Saxony, as the duchy (finally a kingdom). When the Upper was dropped from Upper Saxony, a different region had acquired the Saxon name, ultimately replacing the name's original meaning.

The Finns and Estonians have changed their usage of the term Saxony over the centuries to denote the whole country of Germany (Saksa and Saksamaa respectively) and the Germans (saksalaiset and sakslased, respectively) now. In old Finnish the word saksa meant merchant, as in the words voisaksa (butter seller) and kauppasaksa (traveling salesman), in Estonian saks means master.

The label "Saxons" (in Romanian 'Saşi') was also applied to German settlers who migrated during the 13th century to southeastern Transylvania.

In the Celtic languages, the word for the English nationality is derived from the word Saxon. The most prominent example, often used in English, is the Gàidhlig loanword Sassenach (Saxon), often used disparagingly in Scottish English/Scots. England, in Gàidhlig, is Sasainn (Saxony). Other examples are the Welsh Saesneg (the English language), Irish Sasana (England), Breton Saozneg (the English language), and Cornish Sowson (English people) and Sowsnek (English language), as in the famous My ny vynnav kows Sowsnek! (I will not speak English!).

During Georg Friederich Händel's visit to Italy, much was made of his being from Saxony; in particular, the Venetians greeted the 1709 performance of his opera Agrippina with the cry Viva il caro Sassone, "Long live the beloved Saxon!"[29]

The word also survives as the surnames Saß/Sass, Sachse and Sachs. The Dutch female first name "Saskia" originally meant "A Saxon woman" (alteration of "Saxia").

Notes

- ↑ Germans set up an apartheid-like society in Britain

- ↑

"Saxony". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913.

"Saxony". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. - ↑ Green, D. H. & Siegmund, F.: The Continental Saxons from the Migration Period to the Tenth Century: An Ethnographic Perspective, Boydell Press, 2003 pages 14-15 ISBN 1843830264, 9781843830269

- ↑ Burton, Mark (2002). Milites deBec Equipment.Retrieved 27 September 2005.

- ↑ "they are much given to devil worship," Einhard said, "and they are hostile to our religion," as when they martyred the Saints Ewald

- ↑ Bachrach, p.39.

- ↑ Bachrach, p.39

- ↑ Stenton, 12.

- ↑ Bachrach, 10.

- ↑ Bachrach, 52.

- ↑ Bachrach, 63.

- ↑ Fredegar, IV.54, p. 66.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Goldberg, 473.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Goldberg, 471.

- ↑ Goldberg, 472.

- ↑ Goldberg, 476.

- ↑ Goldberg, 479.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Goldberg, 474.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Stenton, 97–98.

- ↑ Stenton

- ↑ Goldberg, 480.

- ↑ Stenton, 102.

- ↑ Goldberg

- ↑ Goldberg, 478.

- ↑ Hummer, 141, based on Astronomus.

- ↑ Hummer, 143.

- ↑ Goldberg, 477.

- ↑ Hummer, 138–139.

- ↑ Barber, David W. (1996). Bach, Beethoven And the Boys: Music History as it Ought to be Taught. Sound and Vision, Toronto ISBN 0-920151-10-8

References

- Thompson, James Westfall. Feudal Germany. 2 vol. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 1928.

- Reuter, Timothy. Germany in the Early Middle Ages 800–1056. New York: Longman, 1991.

- Reuter, Timothy (trans.) The Annals of Fulda. (Manchester Medieval series, Ninth-Century Histories, Volume II.) Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1992.

- Wallace-Hadrill, J. M., translator. The Fourth Book of the Chronicle of Fredegar with its Continuations. Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1960.

- Stenton, Sir Frank M. Anglo-Saxon England. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Bachrach, Bernard S. Merovingian Military Organization, 481–751. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971.

- Goldberg, Eric J. "Popular Revolt, Dynastic Politics, and Aristocratic Factionalism in the Early Middle Ages: The Saxon Stellinga Reconsidered." Speculum, Vol. 70, No. 3. (Jul., 1995), pp 467–501.

- Hummer, Hans J. Politics and Power in Early Medieval Europe: Alsace and the Frankish Realm 600–1000. Cambridge University Press: 2005.

External links

- James Grout: Saxon Advent, part of the Encyclopædia Romana

- Saxons and Britons

- Info Britain: Saxon Britain

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||