Samanids

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Greater Iran | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| until the rise of modern nation-states | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pre-modern | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History of Afghanistan | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|||||||||||||||||

| See also | |||||||||||||||||

| Ariana · Khorasan | |||||||||||||||||

| Timeline | |||||||||||||||||

|

Pre-Islamic period

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Islamic conquest

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

Modern history

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|

The Samani dynasty (Persian: سلسلهٔ سامانیان), also known as the Samanid Empire, or simply Samanids (819–999)[1] (Persian: سامانیان Sāmāniyān) was an important Persian state[2] and empire[3] in Central Asia and Greater Khorasan, named after its founder Saman Khuda who converted to Sunni Islam[4] despite being from Zoroastrian theocratic nobility. It was the first native Persian dynasty in Greater Iran and Central Asia after the Arab conquest and the collapse of the Sassanid Persian empire. During the Samanid period the Tajik nation was formed in Central Asia. The Samanid Empire is considered as the first Tajik state.

Contents |

Domination

The Samanids are considered an important Persian state.[5] Their rule lasted for 180 years, and their territory encompassed Khorasan, Ray, Transoxiania, Tabaristan, Kerman, Gorgan, and the area west of these provinces up to Isfahan. The Samanids were descendants of Bahram Chobin,[6][7] and thus descended from the House of Mihrān, one of the Seven Great Houses of Iran. In governing their territory, the Samanids modeled their state organization after the Abbasids, mirroring the caliph's court and organization.[8] They were rewarded for supporting the Abbasids in Transoxania and Khorasan, and with their established capitals located in Bukhara, Balkh, Samarkand, and Herat, they carved their kingdom after defeating the Saffarids.[6]

With their roots stemming from the city of Balkh (then, part of Greater Khorasan)[9][10][11] the Samanids promoted the arts, giving rise to the advancement of science and literature, and thus attracted scholars such as Rudaki and Avicenna. While under Samanid control, Bukhara was a rival to Baghdad in its glory.[4] Scholars note that the Samanids revived Persian more than the Buyids and the Saffarids, while continuing to patronize Arabic to a significant degree.[4] Nevertheless, in a famous edict, Samanid authorities declared that "here, in this region, the language is Persian, and the kings of this realm are Persian kings."[4]

History

The Samanid Empire was the first native dynasty to arise in Iran after the Muslim Arab conquest. It was renowned for the impulse that it gave to Iranian national sentiment and learning.

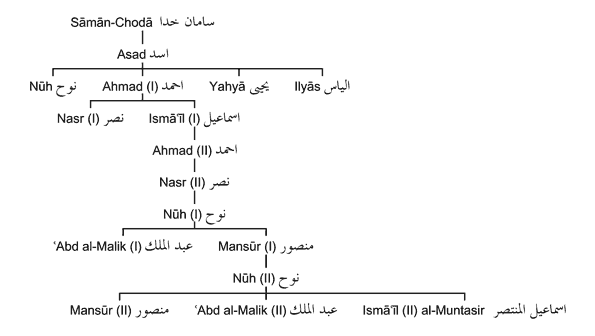

The four grandsons of the dynasty's founder, Saman-Khoda, had been rewarded with provinces for their faithful service to the Abbasid caliph al-Mamun: Nuh obtained Samarkand; Ahmad, Fergana; Yahya, Shash; and Elyas, Herat. Ahmad's son Nasr became governor of Transoxania in 875, but it was his brother and successor, Ismail I (892-907), who overthrew the Saffarids in Khorasan (900) and the Zaydites of Tabaristan, thus establishing a semiautonomous rule over Transoxania and Khorasan, with Bukhara as his capital.

Cultural and religious legacy

The Samanids not only revived Persian culture but they also determinedly propagated Sunni Islam. In doing so, the Samanids repressed Ismaili Shiism[13] but remained tolerant of Twelver Shiism.[4] The Samanid state became a staunch patron of Islamic architecture and spread the Islamo-Persian culture deep into the heart of Central Asia. The population within its areas began firmly accepting Islam in significant numbers, notably in Taraz, now in modern day Kazakhstan. The first complete translation of the Qur'an into Persian occurred during the reign of Samanids in the 9th century.

According to historians, through the zealous missionary work of Samanid rulers, as many as 30,000 tents of Turks came to profess Islam and later under the Ghaznavids higher than 55,000 under the Hanafi school of thought.[4] The mass conversion of the Turks to Islam eventually led to a growing influence of the Ghaznavids, who would later rule the region.

Agriculture and trading were the economic basis of Samanid State. The Samanids were heavily involved in trading - even with Europe, as thousands of Samanid coins that have been found in the Baltic and Scandinavian countries testify[14].

Another lasting contribution of the Samanids to the history of Islamic art is the pottery known as Samanid Epigraphic Ware: plates, bowls, and pitchers fired in a white slip and decorated only with calligraphy, often elegantly and rhythmically written. The Arabic phrases used in this calligraphy are generally more or less generic well wishes, or Islamic admonitions to good table manners. In 999 their realm was conquered by the Karakhanids.

Under Ghaznavid rule, the Shahnameh, was completed. In commending the Samanids, the epic Persian poet Ferdowsi says of them:

کجا آن بزرگان ساسانیان

زبهرامیان تا بسامانیان

"Where have all the great Sassanids gone?

From the Bahrāmids to the Samanids what has come upon?"

Samanid Amirs

- Saman Khuda

- Asad ibn Saman

- Yahya ibn Asad (819-855)

- Nasr I (864 - 892) (Effectively independent 875)

- Ismail (892 - 907)

- Ahmad (907 - 914)

- Nasr II (914 - 943)

- Nuh I (943 - 954)

- 'Abd al-Malik I (954 - 961)

- Mansur I (961 - 976)

- Nuh II (976 - 997)

- Mansur II (997 - 999)

- 'Abd al-Malik II (999)

See also

- Persian empire

- History of Iran

- Greater Khorasan

- Full list of Iranian Kingdoms

- List of Sunni Muslim dynasties

Notes

- ↑ Encyclopedia Britannica, Online Edition, 2007, Samani Dynasty, LINK

- ↑ Islam after communism: religion and politics in Central Asia By Adeeb Khalid, pg. 148

- ↑

- A historical atlas of Uzbekistan, By Aisha Khan, Published by The Rosen Publishing Group, 2003, ISBN 0823938689, 9780823938681, pg. 23;

- The Cambridge History of Iran, By Richard Nelson Frye, William Bayne Fisher, John Andrew Boyle, Published by Cambridge University Press, 1975, ISBN 0521200938, 9780521200936, pg. 164;

- The New Encyclopaedia Britannica, By Encyclopaedia Britannica Publishers, Inc. Staff, Encyclopaedia Britannica, inc, Published by Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1987, ISBN 0852294433, 9780852294437, pg. 891;

- The monumental inscriptions from early Islamic Iran and Transoxiana, By Sheila Blair, Published by BRILL, 1992, ISBN 9004093672, 9789004093676, pg. 27.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 The History of Iran By Elton L. Daniel, pg. 74

- ↑ Tajikistan in the New Central Asia, By Lena Jonson, pg. 18

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Iran and America: Re-Kind[l]ing a Love Lost By Badi Badiozamani, Ghazal Badiozamani, pg. 123

- ↑ History of Bukhara by Narshakhi, Chapter XXIV, Pg 79

- ↑ The Monumental Inscriptions from Early Islamic Iran and Transoxiana By Sheila S. Blair, pg. 27

- ↑ Iranica, "ASAD B. SĀMĀNḴODĀ, ancestor of the Samanid dynasty" [1]

- ↑ Britannica, "The Samanids", Their eponym was Sāmān-Khodā, a landlord in the district of Balkh and, according to the dynasty’s claims, a descendant of Bahrām Chūbīn, the Sāsānian general.[2] or [3]

- ↑ Kamoliddin, Shamsiddin S. "To the Question of the Origin of the Samanids", Transoxiana: Journal Libre de Estudios Orientales, [4]

- ↑ Bowl with white slip, incised design, colored, and glazed. Excavated at Sabz Pushan, Neishapur, Iran. 9th-early 10th century. New York Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ↑ An Ismaili Heresiography: The "Bab Al-Shaytan" from Abu Tammam's Kitab Al ... By Wilferd Madelung, Paul Ernest Walker, pg. 5

- ↑ History of Bukhara, By Narshakhi trans. Richard N. Frye, pg. 143