Sekhmet

| Sekhmet | |

|---|---|

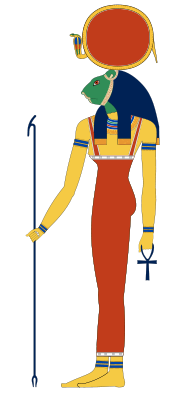

Sekhmet with head of lioness and a solar disk and uraeus on her head |

|

| Goddess of warfare, pestilence and the desert | |

| Major cult center | Memphis, Leontopolis |

| Symbol | Sun disk, red linen |

| Parents | Ra ? |

| Siblings | Presumably Hathor, Bast, Serket, Shu, and Tefnut |

| Consort | Ptah |

In Egyptian mythology, Sekhmet (also spelled Sachmet, Sakhet, Sekmet, Sakhmet and Sekhet; and given the Greek name, Sachmis), was originally the warrior goddess of Upper Egypt. She is depicted as a lioness, the fiercest hunter known to the Egyptians. It was said that her breath created the desert. She was seen as the protector of the pharaohs and led them in warfare.

Her cult was so dominant in the culture that when the first pharaoh of the twelfth dynasty, Amenemhat I, moved the capital of Egypt to Itjtawy, the centre for her cult was moved as well. Religion, the royal lineage, and the authority to govern were intrinsically interwoven in Ancient Egypt during its approximately three thousand years of existence.

Sekhmet also is a solar deity, often considered an aspect of the goddesses Hathor and Bast. She bears the solar disk and the Uraeus which associates her with Wadjet and royalty. With these associations she can be construed as being a divine arbiter of the goddess Ma'at (Justice, or Order) in the Judgment Hall of Osiris, The Eye of Horus, and connecting her with Tefnut as well.

Contents |

History

Upper Egypt is in the south and Lower Egypt is in the delta region in the north. As Lower Egypt had been conquered by Upper Egypt, Sekhmet (lioness) was seen as the more powerful of the two warrior goddesses, the other, Bast (cat), being the similar warrior goddess of Lower Egypt. Consequently, it was Sekhmet who was seen as the Avenger of Wrongs, and the Scarlet Lady,[1] a reference to blood, as the one with bloodlust. She also was seen as a special goddess for women, ruling over menstruation. Unable to be eliminated completely however, Bast became a lesser deity and even was marginalized as Bastet by the priests of Amun who added a second female ending to her name that may have implied a diminutive status, becoming seen as a domestic cat at times.

Sekhmet became identified in some later cults as a daughter of the new sun god, Ra, when his cult merged with and supplanted the worship of Horus (the son of Osiris and Isis, who was one of the oldest of Egyptian deities and gave birth daily to the sun). At that time many roles of deities were changed in the Egyptian myths. Some were changed further when the Greeks established a royal line of rulers that lasted for three hundred years and some of their historians tried to create parallels between deities in the two pantheons.

Her name suits her function and means, the (one who is) powerful. She also was given titles such as the (One) Before Whom Evil Trembles, the Mistress of Dread, and the Lady of Slaughter.

Sekhmet was believed to protect the pharaoh in battle, stalking the land, and destroying the pharaoh's enemies with arrows of fire. An early Egyptian sun deity also, her body was said to take on the bright glare of the midday sun, gaining her the title Lady of Flame. It was said that death and destruction were balm for her warrior's heart and that the hot desert winds were believed to be her breath.[1]

In order to placate Sekhmet's wrath, her priestesses performed a ritual before a different statue of the goddess on each day of the year. This practice resulted in many images of the goddess being preserved. Most of her statuettes were rigidly crafted and do not exhibit any expression of movements or dynamism; this design was made to make them last a long time rather than to express any form of functions or actions she is associated with. It is estimated that more than seven hundred statues of Sekhmet once stood in one funerary temple alone, that of Amenhotep III, on the west bank of the Nile. It was said that her statues were protected from theft or vandalism by coating them with anthrax.

Sekhmet also was seen as a bringer of disease as well as the provider of cures to such ills. The name "Sekhmet" literally became synonymous with physicians and surgeons during the Middle Kingdom. In antiquity, many members of Sekhmet's priesthood often were considered to be on the same level as physicians.

She was envisioned as a fierce lioness, and in art, was depicted as such, or as a woman with the head of a lioness, who was dressed in red, the colour of blood. Sometimes the dress she wears exhibits a rosetta pattern over each nipple, an ancient leonine motif, which can be traced to observation of the shoulder-knot hairs on lions. Occasionally, Sekhmet was also portrayed in her statuettes and engravings with minimal clothing or naked. Tame lions were kept in temples dedicated to Sekhmet at Leontopolis.

Festivals and evolution

To pacify Sekhmet, festivals were celebrated at the end of battle, so that the destruction would come to an end. During an annual festival held at the beginning of the year, a festival of intoxication, the Egyptians danced and played music to soothe the wildness of the goddess and drank great quantities of beer ritually to imitate the extreme drunkenness that stopped the wrath of the goddess—when she almost destroyed humankind. This may relate to averting excessive flooding during the inundation at the beginning of each year as well, when the Nile ran blood-red with the silt from upstream and Sekhmet had to swallow the overflow to save humankind.

In 2006, Betsy Bryan, an archaeologist with Johns Hopkins University excavating at the temple of Mut presented her findings about the festival that included illustrations of the priestesses being served to excess and its adverse effects being ministered to by temple attendants.[2] Participation in the festival was great, including the priestesses and the population. Historical records of tens of thousands attending the festival exist. These findings were made in the temple of Mut because when Thebes rose to greater prominence, Mut absorbed the warrior goddesses as some of her aspects. First, Mut became Mut-Wadjet-Bast, then Mut-Sekhmet-Bast (Wadjet having merged into Bast), then Mut also assimilated Menhit, another lioness goddess, and her adopted son's wife, becoming Mut-Sekhmet-Bast-Menhit, and finally becoming Mut-Nekhbet. These temple excavations at Luxor discovered a "porch of drunkenness" built onto the temple by the Pharaoh Hatshepsut, during the height of her twenty year reign.

In a later myth developed around an annual drunken Sekhmet festival, Ra (who created himeself), by then the sun god of Upper Egypt, created her from a fiery eye gained from his mother, Hathor (daughter of Ra), to destroy mortals who conspired against him (Lower Egypt). In the myth, Sekhmet's blood-lust was not quelled at the end of battle and led to her destroying almost all of humanity, so Ra had tricked her by turning the Nile as red as blood (the Nile turns red every year when filled with silt during inundation) so that Sekhmet would drink it. The trick was, however, that the red liquid was not blood, but beer mixed with pomegranate juice so that it resembled blood, making her so drunk that she gave up slaughter and became an aspect of the gentle Hathor to some moderns.

After Sekhmet's worship was moved to Memphis, Horus the Elder (whose eyes were the sun and the moon) and Ra had been identified as one another (or allies) under the name Ra-Horakhty (with many variant spellings) and so when the two religious systems were merged and Ra became seen as a form of Atum, known as Atum-Ra, Sekhmet (the lioness daughter of Ra), as a form of Hathor (the cow goddess and the mother of the sun who gives birth anew to it every day), was seen as Atum's mother. She then was seen as the mother of Nefertum, the youthful form of Atum who emerged in later myths, and so was said to have Ptah, Nefertum's father, as a husband — as were most of the goddesses when they acquired counterparts as paired deities.

Although Sekhmet again became identified as an aspect of Hathor, over time both evolved back into separate deities because the characters of the two goddesses were so vastly different. Later, as noted above, the creation goddess Mut, the great mother, gradually became absorbed into the identities of the patron goddesses, merging with Sekhmet, and also sometimes with Bast.

Sekhmet later was considered to be the mother of Maahes, a deity who appeared during the New Kingdom period. He was seen as a lion prince, the son of the goddess. The late origin of Maahes in the Egyptian pantheon may be the incorporation of a Nubian deity of ancient origin in that culture, arriving during trade and warfare or even, during a period of domination by Nubia. During the Greek occupation of Egypt, note was made of a temple for Maahes that was an auxiliary facility to a large temple to Sekhmet at Taremu in the delta region (likely a temple for Bast originally), a city which the Greeks called Leontopolis, where by that time, an enclosure was provided to house lions.

In popular culture

Sekhmet is referenced in the album The Circus by The Venetia Fair. Sekhmet is the lion.

Death metal band Nile referenced Sekhmet in their song "The Eye Of Ra" on their album Those Whom the Gods Detest.

Sekhmet is used in The 39 Clues book Beyond The Grave and it is the reason why they travel to Cairo.

Sekhmet is also featured in The Red Pyramid written by Rick Riordan.

References

- ↑ Sources from Sekhmet article by Caroline Seawright at Tour Egypt, retrieved December 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Sex and booze figured in Egyptian rites", archaeologists find evidence for ancient version of ‘Girls Gone Wild’. From MSNBC, Oct 30, 2006

External links

- Ancient Egypt: the Mythology - Sekhmet

- Temple of Sekhmet, in Cactus Springs, Nevada

- "Ancient war goddess statues unearthed in Egypt", archaeologists unearth six statues of the lion-headed war goddess Sekhmet in temple of pharaoh Amenhotep III. 2006-03-06

- Sharayat Sakhmat GLBT Indigenist group dedicated to Sekhmet Kemetism

|

||||||||||||||||||||