Orthogonal group

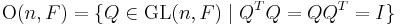

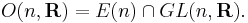

In mathematics, the orthogonal group of degree n over a field F (written as O(n,F)) is the group of n-by-n orthogonal matrices with entries from F, with the group operation that of matrix multiplication. This is a subgroup of the general linear group GL(n,F) given by

where QT is the transpose of Q. The classical orthogonal group over the real numbers is usually just written O(n).

More generally the orthogonal group of a non-singular quadratic form over F is the group of linear operators preserving the form (the above group O(n, F) is then the orthogonal group of the sum-of-n-squares quadratic form). The Cartan–Dieudonné theorem describes the structure of the orthogonal group.

The special orthogonal group, SO(n,F), is the kernel of the Dickson invariant and usually has index 2 in O(n,F).[1] When the characteristic of F is not 2, the Dickson Invariant is 0 whenever the determinant is 1. Thus when the characteristic is not 2, SO(n,F) is commonly defined to be the elements of O(n,F) with determinant 1. Each element in O(n,F) has determinant −1 or 1. Thus in characteristic 2, the determinant is always 1. By analogy with GL/SL (general linear group, special linear group), the orthogonal group is sometimes called the general orthogonal group and denoted GO.

The derived subgroup Ω(n,F) of O(n,F) is an often studied object because when F is a finite field Ω(n,F) is often a finite simple group, a Chevalley group of type Dn. By the Jordan–Hölder Theorem, the finite simple groups are building blocks of finite groups much as the prime numbers are to the integers. The classification of finite simple groups is believed to be complete making Ω(n,F) one of many groups central to the study of group theory.

Both O(n,F) and SO(n,F) are algebraic groups, because the condition that a matrix be orthogonal, i.e. have its own transpose as inverse, can be expressed as a set of polynomial equations in the entries of the matrix.

| Group theory | ||||||||

|

||||||||

Group theory

|

||||||||

| Lie groups | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

Over the real number field

Over the field R of real numbers, the orthogonal group O(n,R) and the special orthogonal group SO(n,R) are often simply denoted by O(n) and SO(n) if no confusion is possible. They form real compact Lie groups of dimension n(n − 1)/2. O(n,R) has two connected components, with SO(n,R) being the identity component, i.e., the connected component containing the identity matrix.

The real orthogonal and real special orthogonal groups have the following geometric interpretations

O(n,R) is a subgroup of the Euclidean group E(n), the group of isometries of Rn; it contains those that leave the origin fixed –  It is the symmetry group of the sphere (n = 3) or hypersphere and all objects with spherical symmetry, if the origin is chosen at the center.

It is the symmetry group of the sphere (n = 3) or hypersphere and all objects with spherical symmetry, if the origin is chosen at the center.

SO(n,R) is a subgroup of E+(n), which consists of direct isometries, i.e., isometries preserving orientation; it contains those that leave the origin fixed –  It is the rotation group of the sphere and all objects with spherical symmetry, if the origin is chosen at the center.

It is the rotation group of the sphere and all objects with spherical symmetry, if the origin is chosen at the center.

{ I, −I } is a normal subgroup and even a characteristic subgroup of O(n,R), and, if n is even, also of SO(n,R). If n is odd, O(n,R) is the direct product of SO(n,R) and { I, −I }. The cyclic group of k-fold rotations Ck is for every positive integer k a normal subgroup of O(2,R) and SO(2,R).

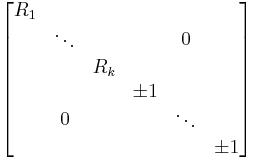

Relative to suitable orthogonal bases, the isometries are of the form:

where the matrices R1,...,Rk are 2-by-2 rotation matrices. The orthogonal group is generated by reflections (two reflections give a rotation), as in a Coxeter group,[note 1] and elements have length at most n (require at most n reflections to generate; this follows from the above classification, noting that a rotation is generated by 2 reflections, and is true more generally for indefinite orthogonal groups, by the Cartan–Dieudonné theorem). A longest element (element needing the most reflections) is reflection through the origin (the map  ), though so are other maximal combinations of rotations (and a reflection, in odd dimension).

), though so are other maximal combinations of rotations (and a reflection, in odd dimension).

The symmetry group of a circle is O(2,R), also called Dih (S1), where S1 denotes the multiplicative group of complex numbers of absolute value 1.

SO(2,R) is isomorphic (as a Lie group) to the circle S1 (circle group). This isomorphism sends the complex number exp(φi) = cos(φ) + i sin(φ) to the orthogonal matrix

The group SO(3,R), understood as the set of rotations of 3-dimensional space, is of major importance in the sciences and engineering. See rotation group and the general formula for a 3 × 3 rotation matrix in terms of the axis and the angle.

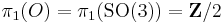

In terms of algebraic topology, for n > 2 the fundamental group of SO(n,R) is cyclic of order 2, and the spinor group Spin(n) is its universal cover. For n = 2 the fundamental group is infinite cyclic and the universal cover corresponds to the real line (the spinor group Spin(2) is the unique 2-fold cover).

Even and odd dimension

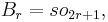

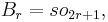

The structure of the orthogonal group differs in certain respects between even and odd dimensions – for example,  (reflection through the origin) is orientation-preserving in even dimension, but orientation-reversing in odd dimension. When this distinction wishes to be emphasized, the groups are generally denoted O(2k) and O(2k+1), reserving n for the dimension of the space (

(reflection through the origin) is orientation-preserving in even dimension, but orientation-reversing in odd dimension. When this distinction wishes to be emphasized, the groups are generally denoted O(2k) and O(2k+1), reserving n for the dimension of the space ( or

or  ). The letters p or r are also used, indicating the rank of the corresponding Lie algebra; in odd dimension the corresponding Lie algebra is

). The letters p or r are also used, indicating the rank of the corresponding Lie algebra; in odd dimension the corresponding Lie algebra is  while in even dimension the Lie algebra is

while in even dimension the Lie algebra is

Lie algebra

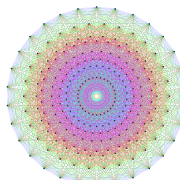

The Lie algebra associated to the Lie groups O(n,R) and SO(n,R) consists of the skew-symmetric real n-by-n matrices, with the Lie bracket given by the commutator. This Lie algebra is often denoted by o(n,R) or by so(n,R), and called the orthogonal Lie algebra or special orthogonal Lie algebra. These Lie algebras are the compact real forms of two of the four families of semisimple Lie algebras: in odd dimension  while in even dimension

while in even dimension

More intrinsically, given a vector space with an inner product, the special orthogonal Lie algebra is given by the bivectors on the space, which are sums of simple bivectors (2-blades)  . The correspondence is given by the map

. The correspondence is given by the map  where

where  is the covector dual to the vector v; in coordinates these are exactly the elementary skew-symmetric matrices.

is the covector dual to the vector v; in coordinates these are exactly the elementary skew-symmetric matrices.

This characterization is used in interpreting the curl of a vector field (naturally a 2-vector) as an infinitesimal rotation or "curl", hence the name. Generalizing the inner product with a nondegenerate form yields the indefinite orthogonal Lie algebras

The representation theory of the orthogonal Lie algebras includes both representations corresponding to linear representations of the orthogonal groups, and representations corresponding to projective representations of the orthogonal groups (linear representations of spin groups), the so-called spin representation, which are important in physics.

3D isometries that leave the origin fixed

Isometries of R3 that leave the origin fixed, forming the group O(3,R), can be categorized as:

- SO(3,R):

- identity

- rotation about an axis through the origin by an angle not equal to 180°

- rotation about an axis through the origin by an angle of 180°

- the same with inversion in the origin (x is mapped to −x), i.e. respectively:

- inversion in the origin

- rotation about an axis by an angle not equal to 180°, combined with reflection in the plane through the origin perpendicular to the axis

- reflection in a plane through the origin

The 4th and 5th in particular, and in a wider sense the 6th also, are called improper rotations.

See also the similar overview including translations.

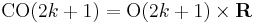

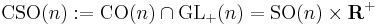

Conformal group

Being isometries (preserving distances), orthogonal transforms also preserve angles, and are thus conformal maps, though not all conformal linear transforms are orthogonal. In classical terms this is the difference between congruence and similarity, as exemplified by SSS (Side-Side-Side) congruence of triangles and AAA (Angle-Angle-Angle) similarity of triangles. The group of conformal linear maps of Rn is denoted CO(n) for the conformal orthogonal group, and consists of the product of the orthogonal group with the group of dilations. If n is odd, these two subgroups do not intersect, and they are a direct product:  , while if n is even, these subgroups intersect in

, while if n is even, these subgroups intersect in  , so this is not a direct product, but it is a direct product with the subgroup of dilation by a positive scalar:

, so this is not a direct product, but it is a direct product with the subgroup of dilation by a positive scalar:  .

.

Similarly one can define CSO(n); note that this is always : .

.

Over the complex number field

Over the field C of complex numbers, O(n,C) and SO(n,C) are complex Lie groups of dimension n(n − 1)/2 over C (which means the dimension over R is twice that). O(n,C) has two connected components, and SO(n,C) is the connected component containing the identity matrix. For n ≥ 2 these groups are noncompact.

Just as in the real case SO(n,C) is not simply connected. For n > 2 the fundamental group of SO(n,C) is cyclic of order 2 whereas the fundamental group of SO(2,C) is infinite cyclic.

The complex Lie algebra associated to O(n,C) and SO(n,C) consists of the skew-symmetric complex n-by-n matrices, with the Lie bracket given by the commutator.

Topology

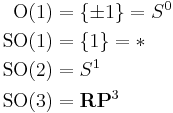

Low dimensional

The low dimensional (real) orthogonal groups are familiar spaces:

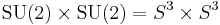

The group  is double covered by

is double covered by  .

.

Here Sn denotes the n-dimensional sphere, RPn the n-dimensional real projective space, and SU(n) the special unitary group of degree n.

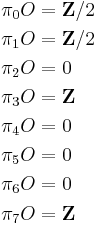

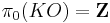

Homotopy groups

The homotopy groups of the orthogonal group are related to homotopy groups of spheres, and thus are in general hard to compute.

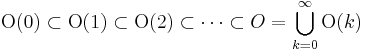

However, one can compute the homotopy groups of the stable orthogonal group (aka the infinite orthogonal group), defined as the direct limit of the sequence of inclusions

(as the inclusions are all closed inclusions, hence cofibrations, this can also be interpreted as a union).

is a homogeneous space for

is a homogeneous space for  , and one has the following fiber bundle:

, and one has the following fiber bundle:

,

,

which can be understood as "The orthogonal group  acts transitively on the unit sphere

acts transitively on the unit sphere  , and the stabilizer of a point (thought of as a unit vector) is the orthogonal group of the perpendicular complement, which is an orthogonal group one dimension lower". The map

, and the stabilizer of a point (thought of as a unit vector) is the orthogonal group of the perpendicular complement, which is an orthogonal group one dimension lower". The map  is the natural inclusion.

is the natural inclusion.

Thus the inclusion  is (n − 1)-connected, so the homotopy groups stabilize, and

is (n − 1)-connected, so the homotopy groups stabilize, and  for

for  : thus the homotopy groups of the stable space equal the lower homotopy groups of the unstable spaces.

: thus the homotopy groups of the stable space equal the lower homotopy groups of the unstable spaces.

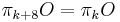

Via Bott periodicity,  , thus the homotopy groups of O are 8-fold periodic, meaning

, thus the homotopy groups of O are 8-fold periodic, meaning  , and one need only compute the lower 8 homotopy groups to compute them all.

, and one need only compute the lower 8 homotopy groups to compute them all.

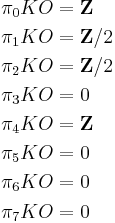

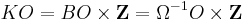

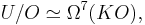

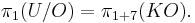

Relation to KO-theory

Via the clutching construction, homotopy groups of the stable space O are identified with stable vector bundles on spheres (up to isomorphism), with a dimension shift of 1:  .

.

Setting  (to make

(to make  fit into the periodicity), one obtains:

fit into the periodicity), one obtains:

Computation and Interpretation of homotopy groups

Low-dimensional groups

The first few homotopy groups can be calculated by using the concrete descriptions of low-dimensional groups.

from orientation-preserving/reversing (this class survives to

from orientation-preserving/reversing (this class survives to  and hence stably)

and hence stably)

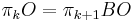

yields

yields

, which is spin

, which is spin , which surjects onto

, which surjects onto  ; this latter thus vanishes

; this latter thus vanishes

Lie groups

From general facts about Lie groups,  always vanishes, and

always vanishes, and  is free (free abelian).

is free (free abelian).

Vector bundles

From the vector bundle point of view,  is vector bundles over

is vector bundles over  , which is two points. Thus over each point, the bundle is trivial, and the non-triviality of the bundle is the difference between the dimensions of the vector spaces over the two points, so

, which is two points. Thus over each point, the bundle is trivial, and the non-triviality of the bundle is the difference between the dimensions of the vector spaces over the two points, so

is dimension

is dimension

Loop spaces

Using concrete descriptions of the loop spaces in Bott periodicity, one can interpret higher homotopy of O as lower homotopy of simple to analyze spaces. Using  , O and O/U have two components,

, O and O/U have two components,  and

and  have

have  components, and the rest are connected.

components, and the rest are connected.

Interpretation of homotopy groups

In a nutshell:[2]

is dimension

is dimension is orientation

is orientation is spin

is spin is topological quantum field theory

is topological quantum field theory

Let  , and let

, and let  be the tautological line bundle over the projective line

be the tautological line bundle over the projective line  , and

, and ![[L_F]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/0e6888233b208932107aaa0819647a1d.png) its class in K-theory. Noting that

its class in K-theory. Noting that  , these yield vector bundles over the corresponding spheres, and

, these yield vector bundles over the corresponding spheres, and

is generated by

is generated by ![[L_{\mathbf R}]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/b2f43f71fc3cc4fbe5e1c38fd1002220.png)

is generated by

is generated by ![[L_{\mathbf C}]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/2652c49d4fbe2ad379e94155f98c04ce.png)

is generated by

is generated by ![[L_{\mathbf H}]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/e0c02ee70f2893f347dbf9925255a567.png)

is generated by

is generated by ![[L_{\mathbf O}]](/2010-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.8_orig_2010-12/I/36b41d3674a48ccefc91229ec620b6f4.png)

From the point of view of symplectic geometry,  can be interpreted as the Maslov index, thinking of it as the fundamental group of the stable Lagrangian Grassmannian

can be interpreted as the Maslov index, thinking of it as the fundamental group of the stable Lagrangian Grassmannian  as

as  so

so

Over finite fields

Orthogonal groups can also be defined over finite fields  , where

, where  is a power of a prime

is a power of a prime  . When defined over such fields, they come in two types in even dimension:

. When defined over such fields, they come in two types in even dimension:  and

and  ; and one type in odd dimension:

; and one type in odd dimension:  .

.

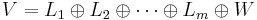

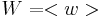

If  is the vector space on which the orthogonal group

is the vector space on which the orthogonal group  acts, it can be written as a direct orthogonal sum as follows:

acts, it can be written as a direct orthogonal sum as follows:

,

,

where  are hyperbolic lines and

are hyperbolic lines and  contains no singular vectors. If

contains no singular vectors. If  , then

, then  is of plus type. If

is of plus type. If  then

then  has odd dimension. If

has odd dimension. If  has dimension 2,

has dimension 2,  is of minus type.

is of minus type.

In the special case where n = 1,  is a dihedral group of order

is a dihedral group of order  .

.

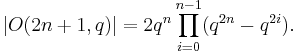

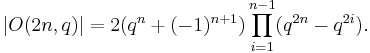

We have the following formulas for the order of these groups, O(n,q) = { A in GL(n,q) : A·At=I }, when the characteristic is greater than two

If −1 is a square in

If −1 is a nonsquare in

The Dickson invariant

For orthogonal groups, the Dickson invariant is a homomorphism from the orthogonal group to Z/2Z, and is 0 or 1 depending on whether an element is the product of an even or odd number of reflections. More concretely, the Dickson Invariant can be defined as  where I is the identity (Taylor 1992, Theorem 11.43). Over fields that are not of characteristic 2 it is equivalent to the determinant: the determinant is −1 to the power of the Dickson invariant. Over fields of characteristic 2, the determinant is always 1, so the Dickson invariant gives extra information. In characteristic 2, the special orthogonal group is defined to be the elements of Dickson invariant 0, rather than the elements of determinant 1.

where I is the identity (Taylor 1992, Theorem 11.43). Over fields that are not of characteristic 2 it is equivalent to the determinant: the determinant is −1 to the power of the Dickson invariant. Over fields of characteristic 2, the determinant is always 1, so the Dickson invariant gives extra information. In characteristic 2, the special orthogonal group is defined to be the elements of Dickson invariant 0, rather than the elements of determinant 1.

The Dickson invariant can also be defined for Clifford groups and Pin groups in a similar way (in all dimensions).

Orthogonal groups of characteristic 2

Over fields of characteristic 2 orthogonal groups often behave differently. This section lists some of the differences.

- Any orthogonal group over any field is generated by reflections, except for a unique example where the vector space is 4 dimensional over the field with 2 elements and the Witt index is 2 (Grove 2002, Theorem 6.6 and 14.16). Note that a reflection in characteristic two has a slightly different definition. In characteristic two, the reflection orthogonal to a vector u takes a vector v to v+B(v,u)/Q(u)·u where B is the bilinear form and Q is the quadratic form associated to the orthogonal geometry. Compare this to the Householder reflection of odd characteristic or characteristic zero, which takes v to v − 2·B(v,u)/Q(u)·u.

- The center of the orthogonal group usually has order 1 in characteristic 2, rather than 2.

- In odd dimensions 2n+1 in characteristic 2, orthogonal groups over perfect fields are the same as symplectic groups in dimension 2n. In fact the symmetric form is alternating in characteristic 2, and as the dimension is odd it must have a kernel of dimension 1, and the quotient by this kernel is a symplectic space of dimension 2n, acted upon by the orthogonal group.

- In even dimensions in characteristic 2 the orthogonal group is a subgroup of the symplectic group, because the symmetric bilinear form of the quadratic form is also an alternating form.

The spinor norm

The spinor norm is a homomorphism from an orthogonal group over a field F to

- F*/F*2,

the multiplicative group of the field F up to square elements, that takes reflection in a vector of norm n to the image of n in F*/F*2.

For the usual orthogonal group over the reals it is trivial, but it is often non-trivial over other fields, or for the orthogonal group of a quadratic form over the reals that is not positive definite.

Galois cohomology and orthogonal groups

In the theory of Galois cohomology of algebraic groups, some further points of view are introduced. They have explanatory value, in particular in relation with the theory of quadratic forms; but were for the most part post hoc, as far as the discovery of the phenomena is concerned. The first point is that quadratic forms over a field can be identified as a Galois H1, or twisted forms (torsors) of an orthogonal group. As an algebraic group, an orthogonal group is in general neither connected nor simply-connected; the latter point brings in the spin phenomena, while the former is related to the discriminant.

The 'spin' name of the spinor norm can be explained by a connection to the spin group (more accurately a pin group). This may now be explained quickly by Galois cohomology (which however postdates the introduction of the term by more direct use of Clifford algebras). The spin covering of the orthogonal group provides a short exact sequence of algebraic groups.

Here μ2 is the algebraic group of square roots of 1; over a field of characteristic not 2 it is roughly the same as a two-element group with trivial Galois action. The connecting homomorphism from H0(OV), which is simply the group OV(F) of F-valued points, to H1(μ2) is essentially the spinor norm, because H1(μ2) is isomorphic to the multiplicative group of the field modulo squares.

There is also the connecting homomorphism from H1 of the orthogonal group, to the H2 of the kernel of the spin covering. The cohomology is non-abelian, so that this is as far as we can go, at least with the conventional definitions.

Related groups

The orthogonal groups and special orthogonal groups have a number of important subgroups, supergroups, quotient groups, and covering groups. These are listed below.

The inclusions  and

and  are part of a sequence of 8 inclusions used in a geometric proof of the Bott periodicity theorem, and the corresponding quotient spaces are symmetric spaces of independent interest – for example,

are part of a sequence of 8 inclusions used in a geometric proof of the Bott periodicity theorem, and the corresponding quotient spaces are symmetric spaces of independent interest – for example,  is the Lagrangian Grassmannian.

is the Lagrangian Grassmannian.

Lie subgroups

In physics, particularly in the areas of Kaluza–Klein compactification, it is important to find out the subgroups of the orthogonal group. The main ones are:

– preserves an axis

– preserves an axis – U(n) are those that preserve a compatible complex structure or a compatible symplectic structure – see 2-out-of-3 property; SU(n) also preserves a complex orientation.

– U(n) are those that preserve a compatible complex structure or a compatible symplectic structure – see 2-out-of-3 property; SU(n) also preserves a complex orientation.

Lie supergroups

The orthogonal group O(n) is also an important subgroup of various Lie groups:

Discrete subgroups

As the orthogonal group is compact, discrete subgroups are equivalent to finite subgroups.[note 2] These subgroups are known as point group and can be realized as the symmetry groups of polytopes. A very important class of examples are the finite Coxeter groups, which include the symmetry groups of regular polytopes.

Dimension 3 is particularly studied – see point groups in three dimensions, polyhedral groups, and list of spherical symmetry groups. In 2 dimensions, the finite groups are either cyclic or dihedral – see point groups in two dimensions.

Other finite subgroups include:

- Permutation matrices (the Coxeter group An)

- Signed permutation matrices (the Coxeter group Bn); also equals the intersection of the orthogonal group with the integer matrices.[note 3]

Covering and quotient groups

The orthogonal group is neither simply connected nor centerless, and thus has both a covering group and a quotient group, respectively:

- Two covering Pin groups, Pin+(n) → O(n) and Pin−(n) → O(n),

- The quotient projective orthogonal group, O(n) → PO(n).

These are all 2-to-1 covers.

For the special orthogonal group, the corresponding groups are:

- Spin group, Spin(n) → SO(n),

- Projective special orthogonal group, SO(n) → PSO(n).

Spin is a 2-to-1 cover, while in even dimension, PSO(2k) is a 2-to-1 cover, and in odd dimension PSO(2k+1) is a 1-to-1 cover, i.e., isomorphic to SO(2k+1). These groups, Spin(n), SO(n), and PSO(n) are Lie group forms of the compact special orthogonal Lie algebra,  – Spin is the simply connected form, while PSO is the centerless form, and SO is in general neither.[note 4]

– Spin is the simply connected form, while PSO is the centerless form, and SO is in general neither.[note 4]

In dimension 3 and above these are the covers and quotients, while dimension 2 and below are somewhat degenerate; see specific articles for details.

Applications to string theory

The group O(10) is of special importance in superstring theory because it is the symmetry group of 10 dimensional space-time.

Principal homogeneous space: Stiefel manifold

The principal homogeneous space for the orthogonal group O(n) is the Stiefel manifold  of orthonormal bases (orthonormal n-frames).

of orthonormal bases (orthonormal n-frames).

In other words, the space of orthonormal bases is like the orthogonal group, but without a choice of base point: given a orthogonal space, there is no natural choice of orthonormal basis, but once one is given one, there is a one-to-one correspondence between bases and the orthogonal group. Concretely, a linear map is determined by where it sends a basis: just as an invertible map can take any basis to any other basis, an orthogonal map can take any orthogonal basis to any other orthogonal basis.

The other Stiefel manifolds  for

for  of incomplete orthonormal bases (orthonormal k-frames) are still homogeneous spaces for the orthogonal group, but not principal homogeneous spaces: any k-frame can be taken to any other k-frame by an orthogonal map, but this map is not uniquely determined.

of incomplete orthonormal bases (orthonormal k-frames) are still homogeneous spaces for the orthogonal group, but not principal homogeneous spaces: any k-frame can be taken to any other k-frame by an orthogonal map, but this map is not uniquely determined.

See also

- Stiefel manifold

Specific transforms

- Coordinate rotations and reflections

- Reflection through the origin

Specific groups

- rotation group, SO(3,R)

- SO(8)

Related groups

- indefinite orthogonal group

- unitary group

- symplectic group

Lists of groups

- list of finite simple groups

- list of simple Lie groups

Notes

- ↑ The analogy is stronger: Weyl groups, a class of (representations of) Coxeter groups, can be considered as simple algebraic groups over the field with one element, and there are a number of analogies between algebraic groups and vector spaces on the one hand, and Weyl groups and sets on the other.

- ↑ Infinite subsets of a compact space have an accumulation point and are not discrete.

- ↑

equals the signed permutation matrices because an integer vector of norm 1 must have a single non-zero entry, which must be ±1 (if it has two non-zero entries or a larger entry, the norm will be larger than 1), and in an orthogonal matrix these entries must be in different coordinates, which is exactly the signed permutation matrices.

equals the signed permutation matrices because an integer vector of norm 1 must have a single non-zero entry, which must be ±1 (if it has two non-zero entries or a larger entry, the norm will be larger than 1), and in an orthogonal matrix these entries must be in different coordinates, which is exactly the signed permutation matrices. - ↑ In odd dimension, SO(2k+1)

PSO(2k+1) is centerless (but not simply connected), while in even dimension SO(2k) is neither centerless nor simply connected.

PSO(2k+1) is centerless (but not simply connected), while in even dimension SO(2k) is neither centerless nor simply connected.

References

- Grove, Larry C. (2002), Classical groups and geometric algebra, Graduate Studies in Mathematics, 39, Providence, R.I.: American Mathematical Society, MR1859189, ISBN 978-0-8218-2019-3

- Taylor, Donald E. (1992), The Geometry of the Classical Groups, 9, Berlin: Heldermann Verlag, MR1189139, ISBN 3-88538-009-9