Rubik's Cube

| Rubik's Cube | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Type | Puzzle |

| Inventor | Ernő Rubik |

| Company | Ideal Toys |

| Country | Hungary |

| Availability | 1974–present |

| Official website | |

The Rubik's Cube is a 3-D mechanical puzzle invented in 1974[1] by Hungarian sculptor and professor of architecture Ernő Rubik. Originally called the "Magic Cube",[2] the puzzle was licensed by Rubik to be sold by Ideal Toys in 1980[3] and won the German Game of the Year special award for Best Puzzle that year. As of January 2009, 350 million cubes have sold worldwide[4][5] making it the world's top-selling puzzle game.[6][7] It is widely considered to be the world's best-selling toy.[8]

In a classic Rubik's Cube, each of the six faces is covered by nine stickers, among six solid colours (traditionally white, red, blue, orange, green, and yellow).[9] A pivot mechanism enables each face to turn independently, thus mixing up the colours. For the puzzle to be solved, each face must be a solid colour. Similar puzzles have now been produced with various numbers of stickers, not all of them by Rubik. The original 3×3×3 version celebrates its thirtieth anniversary in 2010.

Contents |

Conception and development

Prior attempts

In March 1970, Larry Nichols invented a 2×2×2 "Puzzle with Pieces Rotatable in Groups" and filed a Canadian patent application for it. Nichols's cube was held together with magnets. Nichols was granted U.S. Patent 3,655,201 on April 11, 1972, two years before Rubik invented his Cube.

On April 9, 1970, Frank Fox applied to patent his "Spherical 3×3×3". He received his UK patent (1344259) on January 16, 1974.

Rubik's invention

In the mid-1970s, Ernő Rubik worked at the Department of Interior Design at the Academy of Applied Arts and Crafts in Budapest.[10] He sought to find a teaching tool to help his students understand 3D objects. Rubik invented his "Magic Cube" in 1974 and obtained Hungarian patent HU170062 for the Magic Cube in 1975 but did not take out international patents. The first test batches of the product were produced in late 1977 and released to Budapest toy shops. Magic Cube was held together with interlocking plastic pieces that prevented the puzzle being easily pulled apart, unlike the magnets in Nichols's design. In September 1979, a deal was signed with Ideal Toys to bring the Magic Cube to the Western world, and the puzzle made its international debut at the toy fairs of London, Paris, Nuremberg and New York in January and February 1980.

After its international debut, the progress of the Cube towards the toy shop shelves of the West was briefly halted so that it could be manufactured to Western safety and packaging specifications. A lighter Cube was produced, and Ideal Toys decided to rename it. "The Gordian Knot" and "Inca Gold" were considered, but the company finally decided on "Rubik's Cube", and the first batch was exported from Hungary in May 1980. Taking advantage of an initial shortage of Cubes, many imitations appeared.

Patent disputes

Nichols assigned his patent to his employer Moleculon Research Corp., which sued Ideal Toy Company in 1982. In 1984, Ideal lost the patent infringement suit and appealed. In 1986, the appeals court affirmed the judgment that Rubik's 2×2×2 Pocket Cube infringed Nichols's patent, but overturned the judgment on Rubik's 3×3×3 Cube.[11]

Even while Rubik's patent application was being processed, Terutoshi Ishigi, a self-taught engineer and ironworks owner near Tokyo, filed for a Japanese patent for a nearly identical mechanism, which was granted in 1976 (Japanese patent publication JP55-008192). Until 1999, when an amended Japanese patent law was enforced, Japan's patent office granted Japanese patents for non-disclosed technology within Japan without requiring worldwide novelty[12][13]. Hence, Ishigi's patent is generally accepted as an independent reinvention at that time.[14][15][16]

Rubik applied for another Hungarian patent on October 28, 1980, and applied for other patents. In the United States, Rubik was granted U.S. Patent 4,378,116 on March 29, 1983, for the Cube.

Greek inventor Panagiotis Verdes patented[17] a method of creating cubes beyond the 5×5×5, up to 11×11×11, in 2003 although he claims he originally thought of the idea around 1985.[18] As of June 19, 2008, the 5×5×5, 6×6×6, and 7×7×7 models are in production in his "V-Cube" line.

Mechanics

A standard Rubik's cube measures 5.7 cm (approximately 2¼ inches) on each side. The puzzle consists of twenty-six unique miniature cubes, also called "cubies" or "cubelets". Each of these includes a concealed inward extension that interlocks with the other cubes, while permitting them to move to different locations. However, the centre cube of each of the six faces is merely a single square façade; all six are affixed to the core mechanism. These provide structure for the other pieces to fit into and rotate around. So there are twenty-one pieces: a single core piece consisting of three intersecting axes holding the six centre squares in place but letting them rotate, and twenty smaller plastic pieces which fit into it to form the assembled puzzle.

Each of the six center pieces pivots on a screw (fastener) held by the center piece, a "3-D cross". A spring between each screw head and its corresponding piece tensions the piece inward, so that collectively, the whole assembly remains compact, but can still be easily manipulated. The screw can be tightened or loosened to change the "feel" of the Cube. Newer official Rubik's brand cubes have rivets instead of screws and cannot be adjusted.

The Cube can be taken apart without much difficulty, typically by rotating the top layer by 45° and then prying one of its edge cubes away from the other two layers. Consequently it is a simple process to "solve" a Cube by taking it apart and reassembling it in a solved state.

There are twelve edge pieces which show two coloured sides each, and eight corner pieces which show three colours. Each piece shows a unique colour combination, but not all combinations are present (for example, if red and orange are on opposite sides of the solved Cube, there is no edge piece with both red and orange sides). The location of these cubes relative to one another can be altered by twisting an outer third of the Cube 90°, 180° or 270°, but the location of the coloured sides relative to one another in the completed state of the puzzle cannot be altered: it is fixed by the relative positions of the centre squares and the distribution of colour. However, Cubes with alternative colour arrangements also exist; for example, they might have the yellow face opposite the green, and the blue face opposite the white (with red and orange opposite faces remaining unchanged).

Douglas Hofstadter, in the July 1982 issue of Scientific American, pointed out that Cubes could be coloured in such a way as to emphasise the corners or edges, rather than the faces as the standard colouring does; but neither of these alternative colourings has ever become popular.

Mathematics

Permutations

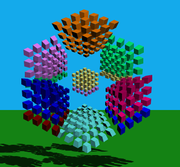

The original (3×3×3) Rubik's Cube has eight corners and twelve edges. There are 8! (40,320) ways to arrange the corner cubes. Seven can be oriented independently, and the orientation of the eighth depends on the preceding seven, giving 37 (2,187) possibilities. There are 12!/2 (239,500,800) ways to arrange the edges, since an odd permutation of the corners implies an odd permutation of the edges as well. Eleven edges can be flipped independently, with the flip of the twelfth depending on the preceding ones, giving 211 (2,048) possibilities.[19]

There are exactly 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 permutations, which is approximately forty-three quintillion. The puzzle is often advertised as having only "billions" of positions, as the larger numbers could be regarded as incomprehensible to many. To put this into perspective, if every permutation of a 57-millimeter Rubik's Cube were lined up end to end, it would stretch out approximately 261 light years.

The preceding figure is limited to permutations that can be reached solely by turning the sides of the cube. If one considers permutations reached through disassembly of the cube, the number becomes twelve times as large:

The full number is 519,024,039,293,878,272,000 or 519 quintillion possible arrangements of the pieces that make up the Cube, but only one in twelve of these are actually solvable. This is because there is no sequence of moves that will swap a single pair of pieces or rotate a single corner or edge cube. Thus there are twelve possible sets of reachable configurations, sometimes called "universes" or "orbits", into which the Cube can be placed by dismantling and reassembling it.

Centre faces

The original Rubik's Cube had no orientation markings on the centre faces, although some carried the words "Rubik's Cube" on the centre square of the white face, and therefore solving it does not require any attention to orienting those faces correctly. However, if one has a marker pen, one could, for example, mark the central squares of an unscrambled Cube with four coloured marks on each edge, each corresponding to the colour of the adjacent face. Some Cubes have also been produced commercially with markings on all of the squares, such as the Lo Shu magic square or playing card suits. Thus one can nominally solve a Cube yet have the markings on the centres rotated; it then becomes an additional test to solve the centers as well.

Marking the Rubik's Cube increases its difficulty because this expands its set of distinguishable possible configurations. When the Cube is unscrambled apart from the orientations of the central squares, there will always be an even number of squares requiring a quarter turn. Thus there are 46/2 = 2,048 possible configurations of the centre squares in the otherwise unscrambled position, increasing the total number of possible Cube permutations from 43,252,003,274,489,856,000 (4.3×1019) to 88,580,102,706,155,225,088,000 (8.9×1022).[20]

Algorithms

In Rubik's cubists' parlance, a memorised sequence of moves that has a desired effect on the cube is called an algorithm. This terminology is derived from the mathematical use of algorithm, meaning a list of well-defined instructions for performing a task from a given initial state, through well-defined successive states, to a desired end-state. Each method of solving the Rubik's Cube employs its own set of algorithms, together with descriptions of what the effect of the algorithm is, and when it can be used to bring the cube closer to being solved.

Most algorithms are designed to transform only a small part of the cube without scrambling other parts that have already been solved, so that they can be applied repeatedly to different parts of the cube until the whole is solved. For example, there are well-known algorithms for cycling three corners without changing the rest of the puzzle, or flipping the orientation of a pair of edges while leaving the others intact.

Some algorithms have a certain desired effect on the cube (for example, swapping two corners) but may also have the side-effect of changing other parts of the cube (such as permuting some edges). Such algorithms are often simpler than the ones without side-effects, and are employed early on in the solution when most of the puzzle has not yet been solved and the side-effects are not important. Towards the end of the solution, the more specific (and usually more complicated) algorithms are used instead, to prevent scrambling parts of the puzzle that have already been solved.

Solutions

Move notation

Many 3×3×3 Rubik's Cube enthusiasts use a notation developed by David Singmaster to denote a sequence of moves, referred to as "Singmaster notation".[21] Its relative nature allows algorithms to be written in such a way that they can be applied regardless of which side is designated the top or how the colours are organised on a particular cube.

- F (Front): the side currently facing you

- B (Back): the side opposite the front

- U (Up): the side above or on top of the front side

- D (Down): the side opposite the top, underneath the Cube

- L (Left): the side directly to the left of the front

- R (Right): the side directly to the right of the front

- ƒ (Front two layers): the side facing you and the corresponding middle layer

- b (Back two layers): the side opposite the front and the corresponding middle layer

- u (Up two layers) : the top side and the corresponding middle layer

- d (Down two layers) : the bottom layer and the corresponding middle layer

- l (Left two layers) : the side to the left of the front and the corresponding middle layer

- r (Right two layers) : the side to the right of the front and the corresponding middle layer

- x (rotate): rotate the entire Cube on R

- y (rotate): rotate the entire Cube on U

- z (rotate): rotate the entire Cube on F

When a prime symbol ( ′ ) follows a letter, it denotes a face turn counter-clockwise, while a letter without a prime symbol denotes a clockwise turn. A letter followed by a 2 (occasionally a superscript 2) denotes two turns, or a 180-degree turn. R is right side clockwise, but R' is right side counter-clockwise. The letters x, y, and z are used to indicate that the entire Cube should be turned about one of its axes. When x, y or z are primed, it is an indication that the cube must be rotated in the opposite direction. When they are squared, the cube must be rotated twice.

For methods using middle-layer turns (particularly corners-first methods) there is a generally accepted "MES" extension to the notation where letters M, E, and S denote middle layer turns. It was used e.g. in Marc Waterman's Algorithm.[22]

- M (Middle): the layer between L and R, turn direction as L (top-down)

- E (Equator): the layer between U and D, turn direction as D (left-right)

- S (Standing): the layer between F and B, turn direction as F

The 4×4×4 and larger cubes use an extended notation to refer to the additional middle layers. Generally speaking, uppercase letters (F B U D L R) refer to the outermost portions of the cube (called faces). Lowercase letters (ƒ b u d ℓ r) refer to the inner portions of the cube (called slices). An asterisk (L*), a number in front of it (2L), or two layers in parenthesis (Lℓ), means to turn the two layers at the same time (both the inner and the outer left faces) For example: (Rr)' ℓ2 ƒ' means to turn the two rightmost layers counterclockwise, then the left inner layer twice, and then the inner front layer counterclockwise.

Optimal solutions

Although there are a significant number of possible permutations for the Rubik's Cube, there have been a number of solutions developed which allow for the cube to be solved in well under 100 moves.

Many general solutions for the Rubik's Cube have been discovered independently. The most popular method was developed by David Singmaster and published in the book Notes on Rubik's "Magic Cube" in 1981. This solution involves solving the Cube layer by layer, in which one layer (designated the top) is solved first, followed by the middle layer, and then the final and bottom layer. After practice, solving the Cube layer by layer can be done in under one minute. Other general solutions include "corners first" methods or combinations of several other methods. In 1982, David Singmaster and Alexander Frey hypothesised that the number of moves needed to solve the Rubik's Cube, given an ideal algorithm, might be in "the low twenties". In 2007, Daniel Kunkle and Gene Cooperman used computer search methods to demonstrate that any 3×3×3 Rubik's Cube configuration can be solved in 26 moves or less.[23][24][25] In 2008, Tomas Rokicki lowered that number to 22 moves,[26][27][28] and in July 2010, a team of researchers including Rokicki, working with Google, proved the so-called "God's number" to be 20.[29][30]

A solution commonly used by speed cubers was developed by Jessica Fridrich. It is similar to the layer-by-layer method but employs the use of a large number of algorithms, especially for orienting and permuting the last layer. The cross is done first followed by first-layer corners and second layer edges simultaneously, with each corner paired up with a second-layer edge piece. This is then followed by orienting the last layer then permuting the last layer (OLL and PLL respectively). Fridrich's solution requires learning roughly 120 algorithms but allows the Cube to be solved in only 55 moves on average.

Philip Marshall's The Ultimate Solution to Rubik's Cube is a modified version of Fridrich's method, averaging only 65 twists yet requiring the memorization of only two algorithms.[31]

A now well-known method was developed by Lars Petrus. In this method, a 2×2×2 section is solved first, followed by a 2×2×3, and then the incorrect edges are solved using a three-move algorithm, which eliminates the need for a possible 32-move algorithm later. The principle behind this is that in layer by layer you must constantly break and fix the first layer; the 2×2×2 and 2×2×3 sections allow three or two layers to be turned without ruining progress. One of the advantages of this method is that it tends to give solutions in fewer moves.

In 1997, Denny Dedmore published a solution described using diagrammatic icons representing the moves to be made, instead of the usual notation.[32]

Competitions and records

Speedcubing competitions

Speedcubing (or speedsolving) is the practice of trying to solve a Rubik's Cube in the shortest time possible. There are a number of speedcubing competitions that take place around the world.

The first world championship organised by the Guinness Book of World Records was held in Munich on March 13, 1981. All Cubes were moved 40 times and lubricated with petroleum jelly. The official winner, with a record of 38 seconds, was Jury Froeschl, born in Munich. The first international world championship was held in Budapest on June 5, 1982, and was won by Minh Thai, a Vietnamese student from Los Angeles, with a time of 22.95 seconds.

Since 2003, the winner of a competition is determined by taking the average time of the middle three of five attempts. However, the single best time of all tries is also recorded. The World Cube Association maintains a history of world records.[33] In 2004, the WCA made it mandatory to use a special timing device called a Stackmat timer.

In addition to official competitions, informal alternative competitions have been held which invite participants to solve the Cube in unusual situations. Some such situations include:

- Blindfolded solving[34]

- Solving the Cube with one person blindfolded and the other person saying what moves to do, known as "Team Blindfold"

- Solving the Cube underwater in a single breath[35]

- Solving the Cube using a single hand[36]

- Solving the Cube with one's feet[37]

Of these informal competitions, the World Cube Association only sanctions blindfolded, one-handed, and feet solving as official competition events.[38]

In blindfolded solving, the contestant first studies the scrambled cube (i.e., looking at it normally with no blindfold), and is then blindfolded before beginning to turn the cube's faces. Their recorded time for this event includes both the time spent examining the cube and the time spent manipulating it.

Records

The current world record for single time on a 3×3×3 Rubik's Cube was set by Erik Akkersdijk in 2008, who had a best time of 7.08 seconds at the Czech Open 2008. The world record average solve is currently held by Feliks Zemdegs; which is 8.52 seconds[39] at the New Zealand Championships 2010.

On March 17, 2010, 134 school boys from Dr Challoner's Grammar School, Amersham, England broke the previous Guinness World Record for most people solving a Rubik's cube at once in 12 minutes.[40] The previous record set in December 2008 in Santa Ana, CA achieved 96 completions.

Variations

There are different variations of Rubik's Cubes with up to seven layers: the 2×2×2 (Pocket/Mini Cube), the standard 3×3×3 cube, the 4×4×4 (Rubik's Revenge/Master Cube), and the 5×5×5 (Professor's Cube), the 6×6×6 (V-Cube 6), and 7×7×7 (V-Cube 7).

CESailor Tech's E-cube is an electronic variant of the 3x3x3 cube, made with RGB LEDs and switches.[41] There are two switches on each row and column. Pressing the switches indicates the direction of rotation, which causes the LED display to change colours, simulating real rotations. The product was demonstrated at the Taiwan government show of College designs on October 30, 2008.

Another electronic variation of the 3×3×3 Cube is the Rubik's TouchCube. Sliding a finger across its faces causes its patterns of coloured lights to rotate the same way they would on a mechanical cube. The TouchCube was introduced at the American International Toy Fair in New York on February 15, 2009.[42][43]

The Cube has inspired an entire category of similar puzzles, commonly referred to as twisty puzzles, which includes the cubes of different sizes mentioned above as well as various other geometric shapes. Some such shapes include the tetrahedron (Pyraminx), the octahedron (Skewb Diamond), the dodecahedron (Megaminx), the icosahedron (Dogic). There are also puzzles that change shape such as Rubik's Snake and the Square One.

Custom-built puzzles

In the past, puzzles have been built resembling the Rubik's Cube or based on its inner workings. For example, a cuboid is a puzzle based on the Rubik's Cube, but with different functional dimensions, such as, 2×3×4, 3×3×5, or 2×2×4. Many cuboids are based on 4×4×4 or 5×5×5 mechanisms, via building plastic extensions or by directly modifying the mechanism itself.

Some custom puzzles are not derived from any existing mechanism, such as the Gigaminx v1.5-v2, Bevel Cube, SuperX, Toru, Rua, and 1×2×3. These puzzles usually have a set of masters 3D printed, which then are copied using molding and casting techniques to create the final puzzle.

Other Rubik's Cube modifications include cubes that have been extended or truncated to form a new shape. An example of this is the Trabjer's Octahedron, which can be built by truncating and extending portions of a regular 3×3. Most shape mods can be adapted to higher-order cubes. In the case of Tony Fisher's Rhombic Dodecahedron, there are 3×3, 4×4, 5×5, and 6×6 versions of the puzzle.

Rubik's Cube software

Puzzles like the Rubik's Cube can be simulated by computer software, which provide functions such as recording of player metrics, storing scrambled Cube positions, conducting online competitions, analyzing of move sequences, and converting between different move notations. Software can also simulate very large puzzles that are impractical to build, such as 100×100×100 and 1,000×1,000×1,000 cubes, as well as virtual puzzles that cannot be physically built, such as 4- and 5-dimensional analogues of the cube.[44][45]

Popular culture

Many movies and TV shows have featured characters that solve Rubik's Cubes quickly to establish their high intelligence. Rubik's cube also regularly feature as motifs in works of art.

See also

- Combination puzzles (also known as "twisty" puzzles)

- N-dimensional sequential move puzzles

- Rubik, the Amazing Cube

- Rubik's 360

- Rubik's cube group

- Sudoku Cube

- Cubage (video game)

- Octacube

- God's algorithm

Notes

- ↑ William Fotheringham (2007). Fotheringham's Sporting Pastimes. Anova Books. pp. 50. ISBN 1-86105-953-1.

- ↑ 'Driven mad' Rubik's nut weeps on solving cube... after 26 years of trying, Daily Mail Reporter, January 12, 2009.

- ↑ Daintith, John (1994). A Biographical Encyclopedia of Scientists. Bristol: Institute of Physics Pub. pp. 771. ISBN 0-7503-0287-9.

- ↑ William Lee Adams (2009-01-28). "The Rubik's Cube: A Puzzling Success". TIME. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1874509,00.html. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ↑ Alastair Jamieson (2009-01-31). "Rubik's Cube inventor is back with Rubik's 360". The Daily Telegraph (London). http://www.telegraph.co.uk/lifestyle/4412176/Rubiks-Cube-inventor-is-back-with-Rubiks-360.html. Retrieved 2009-02-05.

- ↑ "eGames, Mindscape Put International Twist On Rubik's Cube PC Game". Reuters. 2008-02-06. http://www.reuters.com/article/pressRelease/idUS147698+06-Feb-2008+PNW20080206. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ Marshall, Ray. Squaring up to the Rubchallenge. icNewcastle. Retrieved August 15, 2005.

- ↑ "Rubik's Cube 25 years on: crazy toys, crazy times". The Independent (London). 2007-08-16. http://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/rubiks-cube-25-years-on-crazy-toys-crazy-times-461768.html. Retrieved 2009-02-06.

- ↑ Michael W. Dempsey (1988). Growing up with science: The illustrated encyclopedia of invention. London: Marshall Cavendish. pp. 1245. ISBN 0-8747-5841-6.

- ↑ Kelly Boyer Sagert (2007). The 1970s (American Popular Culture Through History). Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. pp. 130. ISBN 0-313-33919-8.

- ↑ Moleculon Research Corporation v. CBS, Inc.

- ↑ Japan: Patents (PCT), Law (Consolidation), 26/04/1978 (22/12/1999), No. 30 (No. 220)

- ↑ Major Amendments to the Japanese Patent Law (since 1985)

- ↑ Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1985). Metamagical Themas. Basic Books.Hofstadter gives the name as "Ishige".

- ↑ Rubik's Cube Chronology Researched and maintained by Mark Longridge (c) 1996-2004

- ↑ The History of Rubik's Cube - Erno Rubik

- ↑ Verdes, PK, Cubic logic game, Greek patent GR1004581, filed May 21, 2003, issued May 26, 2004.

- ↑ Vcube Inventor

- ↑ Martin Schönert "Analyzing Rubik's Cube with GAP": the permutation group of Rubik's Cube is examined with GAP computer algebra system

- ↑ Scientific American, p28, vol 246, 1982 retrieved online Jan 29, 2009.

- ↑ Joyner, David (2002). Adventures in group theory: Rubik's Cube, Merlin's machine, and Other Mathematical Toys. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 7. ISBN 0-8018-6947-1.

- ↑ Treep, Anneke; Waterman, Marc (1987). Marc Waterman's Algorithm, Part 2. Cubism For Fun 15. Nederlandse Kubus Club. p. 10.

- ↑ Kunkle, D.; Cooperman, C. (2007). "Twenty-Six Moves Suffice for Rubik's Cube". Proceedings of the International Symposium on Symbolic and Algebraic Computation (ISSAC '07). ACM Press. http://www.ccs.neu.edu/home/gene/papers/rubik.pdf.

- ↑ KFC (2008). "Rubik’s cube proof cut to 25 moves". http://arxivblog.com/?p=332.

- ↑ Julie J. Rehmeyer. "Cracking the Cube". MathTrek. http://blog.sciencenews.org/mathtrek/2007/08/cracking_the_cube.html. Retrieved 2007-08-09.

- ↑ Tom Rokicki. "Twenty-Five Moves Suffice for Rubik's Cube". http://arxiv.org/abs/0803.3435. Retrieved 2008-03-24.

- ↑ "Rubik's Cube Algorithm Cut Again, Down to 23 Moves". Slashdot. http://science.slashdot.org/article.pl?sid=08/06/05/2054249. Retrieved 2008-06-05.

- ↑ Tom Rokicki. "Twenty-Two Moves Suffice". http://cubezzz.homelinux.org/drupal/?q=node/view/121. Retrieved 2008-08-20.

- ↑ Flatley, Joseph F. (2010-08-09). "Rubik's Cube solved in twenty moves, 35 years of CPU time". Engadget. http://www.engadget.com/2010/08/09/rubiks-cube-solved-in-twenty-moves-35-years-of-cpu-time/. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ↑ Davidson, Morley; Dethridge, John; Kociemba; Rokicki, Tomas. "God's Number is 20". www.cube20.org. http://www.cube20.org/. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ↑ Philip Marshall (2005), The Ultimate Solution to Rubik's Cube.

- ↑ Website with solutions created by Denny Dedmore

- ↑ "World Cube Association Official Results". World Cube Association. http://www.worldcubeassociation.org/results/regions.php?regionId=&eventId=333&years=&history=History. Retrieved 2008-02-16.

- ↑ Rubik's 3x3x3 Cube: Blindfolded records

- ↑ Rubik's Cube 3x3x3: Underwater

- ↑ Rubik's 3x3x3 Cube: One-handed

- ↑ Rubik's 3x3x3 Cube: With feet

- ↑ "Competition Regulations, Article 9: Events". World Cube Association. 2008-04-09. http://www.worldcubeassociation.org/regulations/#events. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ↑ WorldCubeAssociation: Feliks Zemdegs wins New Zealand Championships 2010

- ↑ BBC: Pupils break Rubik's Cube Record

- ↑ CESailor website, retrieved 2009-04-23.

- ↑ "NY Toy Fair opens with new Rubik's Cube, Lego deals". Reuters. 2009-02-16. http://uk.reuters.com/article/rbssConsumerGoodsAndRetailNews/idUKN1546558020090216?sp=true. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ "Toy Fair Kicks Off At Javits Center". http://www.ny1.com/Content/Top_Stories/93988/toy-fair-kicks-off-at-javits-center/Default.aspx. Retrieved 2009-03-23.

- ↑ Magic Cube 4D

- ↑ Magic Cube 5D

References

- Cube Games by Don Taylor & Leanne Rylands

- Four-Axis Puzzles by Anthony E. Durham.

- Handbook of Cubik Math by Alexander H. Frey, Jr. and David Singmaster; Enslow Publishers, Hillside, NJ, USA, 1982, ISBN 0-7188-2555-1

- Mathematics of the Rubik's Cube Design by Hana M. Bizek; ISBN 0-8059-3919-9

- Mastering Rubik's Cube by Don Taylor; Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, UK, 1981, ISBN 0-1400-6102-9

- Metamagical Themas by Douglas R. Hofstadter contains two insightful chapters regarding Rubik's Cube and similar puzzles, "Magic Cubology" and "On Crossing the Rubicon", originally published as articles in the March 1981 and July 1982 issues of Scientific American; ISBN 0-465-04566-9

- Notes on Rubik's 'Magic Cube' by David Singmaster; Penguin Books, Harmondsworth, UK, 1981, ISBN 0-1400-6149-5

- Rubik's Cube Made Easy by Jack Eidswick, Ph.D.

- The Simple Solution to Rubik's Cube by James Nourse; Bantam Books, NY, USA, 1981, ISBN 0-553-14017-5

- Speedsolving The Cube by Dan Harris

- Teach yourself cube-bashing, a layered solution by Colin Cairns and Dave Griffiths, from September 1979, cited by Singmaster's 'Notes on Rubik's Magic Cube'

- Unscrambling The Cube by M. Razid Black & Herbert Taylor, Introduction by Professor Solomon W. Golomb

- University of Michigan's endover cube decorated to look like a Rubik's cube

External links

- Rubik's Cube at the Open Directory Project

- Rubik's official site

- World Cube Association (WCA)

- Speedcubing.com

- Speedsolving.com Wiki

- How to Solve a Rubik's Cube (Video)

- How to Solve a Rubik’s Cube

- More than 2,000 cubes and cubelike puzzles

- Adventures in Group Theory: Rubik's Cube, Merlin's Machine, and Other Mathematical Toys

- A forum for twisty puzzle enthusiasts; includes commentary and advice about making custom puzzles

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||