Rigveda

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures |

|---|

|

| Vedas |

| Rigveda · Yajurveda Samaveda · Atharvaveda |

| Vedangas |

| Shiksha · Chandas Vyakarana · Nirukta Kalpa · Jyotisha |

| Upanishads |

| Rig vedic Aitareya Yajur vedic

Brihadaranyaka · Isha Taittiriya · Katha Shvetashvatara Sama vedic

Chandogya · Kena Atharva vedic

Mundaka · Mandukya Prashna |

| Puranas |

| Brahma puranas Brahma · Brahmānda Brahmavaivarta Markandeya · Bhavishya Shiva puranas

Shiva · Linga Skanda · Vayu |

| Epics |

| Ramayana Mahabharata (Bhagavad Gita) |

| Other scriptures |

| Manu Smriti Artha Shastra · Agama Tantra · Sūtra · Stotra Dharmashastra Divya Prabandha Tevaram Ramcharitmanas Yoga Vasistha |

| Scripture classification |

| Śruti · Smriti |

The Rigveda (Sanskrit: ऋग्वेद ṛgveda, a compound of ṛc "praise, verse"[1] and veda "knowledge") is an ancient Indian sacred collection of Vedic Sanskrit hymns. It is counted among the four canonical sacred texts (śruti) of Hinduism known as the Vedas.[2] Some of its verses are still recited as Hindu prayers, at religious functions and other occasions, putting these among the world's oldest religious texts in continued use. [3]

It is one of the oldest extant texts in any Indo-European language. Philological and linguistic evidence indicate that the Rigveda was composed in the north-western region of the Indian subcontinent, roughly between 1700–1100 BC[4] (the early Vedic period). There are strong linguistic and cultural similarities with the early Iranian Avesta, deriving from the Proto-Indo-Iranian times, often associated with the early Andronovo (Sintashta-Petrovka) culture of ca. 2200-1600 BC.

However there is astrological and astronomical concerns [5] in the dating of the Rig Veda since as Kenoyer holds that the Indus valley script can be traced to at least 3,300 BC—making it as old or older than the oldest Sumerian written records. [6] Using astronomy as a tool to date the Rig Veda is now an accepted methodology and presents a date or origin closer to 3800 BC if not older. [7] [8]

Evidence from other sources known since the late nineteenth century also tends to confirm the great antiquity of the Vedic tradition. Certain Vedic texts, for example, refer to astronomical events that took place in ancient astronomical time.

Professor Colin Renfrew, professor of archeology at Cambridge University, in his Archeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins, (1988) gives evidence for Indo-Europeans in India as early as 6,000 BC and comments:

"As far as I can see there is nothing in the Hymns of the Rigveda which demonstrates that the Vedic-speaking population were intrusive to the area: this comes rather from a historical assumption about the ‘coming’ of the Indo-Europeans." [9]

Attempts to date the Rig Veda based on astronomical evidence have great merit, but the conclusions are hotly debated, and probably not entirely free of conjecture since there has been a bias from a western mindset and an opposing view correlating using astronomy and religious texts. Several contemporary scholars however take them quite seriously as a method of dating the Rig Veda.

Contents |

Text

The surviving form of the Rigveda is based on an early Iron Age (c. 10th c. BC) collection that established the core 'family books' (mandalas 2–7, ordered by author, deity and meter [10]) and a later redaction, co-eval with the redaction of the other Vedas, dating several centuries after the hymns were composed. This redaction also included some additions (contradicting the strict ordering scheme) and orthoepic changes to the Vedic Sanskrit such as the regularization of sandhi (termed orthoepische Diaskeuase by Oldenberg, 1888).

As with the other Vedas, the redacted text has been handed down in several versions, most importantly the Padapatha that has each word isolated in pausa form and is used for just one way of memorization; and the Samhitapatha that combines words according to the rules of sandhi (the process being described in the Pratisakhya) and is the memorized text used for recitation.

The Padapatha and the Pratisakhya anchor the text's fidelity and meaning[11] and the fixed text was preserved with unparalleled fidelity for more than a millennium by oral tradition alone. In order to achieve this the oral tradition prescribed very structured enunciation, involving breaking down the Sanskrit compounds into stems and inflections, as well as certain permutations. This interplay with sounds gave rise to a scholarly tradition of morphology and phonetics. The Rigveda was probably not written down until the Gupta period (4th to 6th century AD), by which time the Brahmi script had become widespread (the oldest surviving manuscripts date to the Late Middle Ages[12]). The oral tradition still continued into recent times.

The original text (as authored by the Rishis) is close to but not identical to the extant Samhitapatha, but metrical and other observations allow to reconstruct (in part at least) the original text from the extant one, as printed in the Harvard Oriental Series, vol. 50 (1994) [13].

Organization

The text is organized in 10 books, known as Mandalas, of varying age and length. The "family books": mandalas 2-7, are the oldest part of the Rigveda and the shortest books; they are arranged by length and account for 38% of the text. The eighth and ninth mandalas, comprising hymns of mixed age, account for 15% and 9%, respectively. The first and the tenth mandalas are the youngest; they are also the longest books, of 191 suktas each, accounting for 37% of the text.

Each mandala consists of hymns called sūkta (su-ukta, literally, "well recited, eulogy") intended for various sacrificial rituals. The sūktas in turn consist of individual stanzas called ṛc ("praise", pl. ṛcas), which are further analysed into units of verse called pada ("foot"). The meters most used in the ṛcas are the jagati (a pada consists of 12 syllables), trishtubh (11), viraj (10), gayatri and anushtubh (8).

For pedagogical convenience, each mandala is synthetically divided into roughly equal sections of several sūktas, called anuvāka ("recitation"), which modern publishers often omit. Another scheme divides the entire text over the 10 mandalas into aṣṭaka ("eighth"), adhyāya ("chapter") and varga ("class"). Some publishers give both classifications in a single edition.

The most common numbering scheme is by book, hymn and stanza (and pada a, b, c ..., if required). E.g., the first pada is

- 1.1.1a agním īḷe puróhitaṃ "Agni I invoke, the housepriest"

and the final pada is

- 10.191.4d yáthā vaḥ súsahā́sati

Recensions

The major Rigvedic shakha ("branch", i. e. recension) that has survived is that of Śākalya. Another shakha that may have survived is the Bāṣkala, although this is uncertain.[14][15][16] The surviving padapatha version of the Rigveda text is ascribed to Śākalya.[17] The Śākala recension has 1,017 regular hymns, and an appendix of 11 vālakhilya hymns[18] which are now customarily included in the 8th mandala (as 8.49–8.59), for a total of 1028 hymns.[19] The Bāṣkala recension includes 8 of these vālakhilya hymns among its regular hymns, making a total of 1025 regular hymns for this śākhā.[20] In addition, the Bāṣkala recension has its own appendix of 98 hymns, the Khilani.[21]

In the 1877 edition of Aufrecht, the 1028 hymns of the Rigveda contain a total of 10,552 ṛcs, or 39,831 padas. The Shatapatha Brahmana gives the number of syllables to be 432,000,[22] while the metrical text of van Nooten and Holland (1994) has a total of 395,563 syllables (or an average of 9.93 syllables per pada); counting the number of syllables is not straightforward because of issues with sandhi and the post-Rigvedic pronunciation of syllables like súvar as svàr.

The Rigveda mentions a library with thousands of documents (sahsra akshare parame vyomen---) kept under the protection of Suryadeva, the last Deva king. It is this library, which has never been found, that the Hindus refer to as the Vedas. The Kalpa branch of the Vedas the knowledge in science and technology has completely disappeared. One branch of the Vedas - Jyotish (Astronomy) has only partly survived.

Rishis

Tradition associates a rishi (the composer) with each ṛc of the Rigveda.[23] Most sūktas are attributed to single composers. The "family books" (2-7) are so-called because they have hymns by members of the same clan in each book; but other clans are also represented in the Rigveda. In all, 10 families of rishis account for more than 95% of the ṛcs; for each of them the Rigveda includes a lineage-specific āprī hymn (a special sūkta of rigidly formulaic structure, used for animal sacrifice in the soma ritual).

| Family | Āprī | Ṛcas[24] |

|---|---|---|

| Angiras | I.142 | 3619 (especially Mandala 6) |

| Kanva | I.13 | 1315 (especially Mandala 8) |

| Vasishtha | VII.2 | 1276 (Mandala 7) |

| Vishvamitra | III.4 | 983 (Mandala 3) |

| Atri | V.5 | 885 (Mandala 5) |

| Bhrgu | X.110 | 473 |

| Kashyapa | IX.5 | 415 (part of Mandala 9) |

| Grtsamada | II.3 | 401 (Mandala 2) |

| Agastya | I.188 | 316 |

| Bharata | X.70 | 170 |

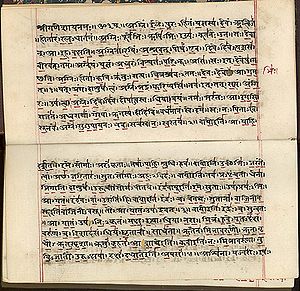

Manuscripts

There are, for example, 30 manuscripts of Rigveda at the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, collected in the 19th century by Georg Bühler, Franz Kielhorn and others, originating from different parts of India, including Kashmir, Gujarat, the then Rajaputana, Central Provinces etc. They were transferred to Deccan College, Pune, in the late 19th century. They are in the Sharada and Devanagari scripts, written on birch bark and paper. The oldest of them is dated to 1464. The 30 manuscripts were added to UNESCO's "Memory of the World" Register in 2007.[25]

Of these 30 manuscripts, 9 contain the samhita text, 5 have the padapatha in addition. 13 contain Sayana's commentary. At least 5 manuscripts (MS. no. 1/A1879-80, 1/A1881-82, 331/1883-84 and 5/Viś I) have preserved the complete text of the Rigveda. MS no. 5/1875-76, written on birch bark in bold Sharada, was only in part used by Max Müller for his edition of the Rigveda with Sayana's commentary.

Müller used 24 manuscripts then available to him in Europe, while the Pune Edition used over five dozen manuscripts, but the editors of Pune Edition could not procure many manuscripts used by Müller and by the Bombay Edition, as well as from some other sources; hence the total number of extant manuscripts known then must surpass perhaps eighty at least[26]

Contents

- See also: Rigvedic deities

The Rigvedic hymns are dedicated to various deities, chief of whom are Indra, a heroic god praised for having slain his enemy Vrtra; Agni, the sacrificial fire; and Soma, the sacred potion or the plant it is made from. Equally prominent gods are the Adityas or Asura gods Mitra–Varuna and Ushas (the dawn). Also invoked are Savitr, Vishnu, Rudra, Pushan, Brihaspati or Brahmanaspati, as well as deified natural phenomena such as Dyaus Pita (the shining sky, Father Heaven ), Prithivi (the earth, Mother Earth), Surya (the sun god), Vayu or Vata (the wind), Apas (the waters), Parjanya (the thunder and rain), Vac (the word), many rivers (notably the Sapta Sindhu, and the Sarasvati River). The Adityas, Vasus, Rudras, Sadhyas, Ashvins, Maruts, Rbhus, and the Vishvadevas ("all-gods") as well as the "thirty-three gods" are the groups of deities mentioned.

The hymns mention various further minor gods, persons, , phenomena and items, and contain fragmentary references to possible historical events, notably the struggle between the early Vedic people (known as Vedic Aryans, a subgroup of the Indo-Aryans) and their enemies, the Dasa or Dasyu and their mythical prototypes, the Paṇi (the Bactrian Parna).

- Mandala 1 comprises 191 hymns. Hymn 1.1 is addressed to Agni, and his name is the first word of the Rigveda. The remaining hymns are mainly addressed to Agni and Indra, as well as Varuna, Mitra, the Ashvins, the Maruts, Usas, Surya, Rbhus, Rudra, Vayu, Brhaspati, Visnu, Heaven and Earth, and all the Gods.

- Mandala 2 comprises 43 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra. It is chiefly attributed to the Rishi gṛtsamada śaunahotra.

- Mandala 3 comprises 62 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra and the Vishvedevas. The verse 3.62.10 has great importance in Hinduism as the Gayatri Mantra. Most hymns in this book are attributed to viśvāmitra gāthinaḥ.

- Mandala 4 comprises 58 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra as well as the Rbhus, Ashvins, Brhaspati, Vayu, Usas, etc. Most hymns in this book are attributed to vāmadeva gautama.

- Mandala 5 comprises 87 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra, the Visvedevas ("all the gods'), the Maruts, the twin-deity Mitra-Varuna and the Asvins. Two hymns each are dedicated to Ushas (the dawn) and to Savitr. Most hymns in this book are attributed to the atri clan.

- Mandala 6 comprises 75 hymns, mainly to Agni and Indra, all the gods, Pusan, Ashvin, Usas, etc. Most hymns in this book are attributed to the bārhaspatya family of Angirasas.

- Mandala 7 comprises 104 hymns, to Agni, Indra, the Visvadevas, the Maruts, Mitra-Varuna, the Asvins, Ushas, Indra-Varuna, Varuna, Vayu (the wind), two each to Sarasvati (ancient river/goddess of learning) and Vishnu, and to others. Most hymns in this book are attributed to vasiṣṭha maitravaruṇi.

- Mandala 8 comprises 103 hymns to various gods. Hymns 8.49 to 8.59 are the apocryphal vālakhilya. Hymns 1-48 and 60-66 are attributed to the kāṇva clan, the rest to other (Angirasa) poets.

- Mandala 9 comprises 114 hymns, entirely devoted to Soma Pavamana, the cleansing of the sacred potion of the Vedic religion.

- Mandala 10 comprises additional 191 hymns, frequently in later language, addressed to Agni, Indra and various other deities. It contains the Nadistuti sukta which is in praise of rivers and is important for the reconstruction of the geography of the Vedic civilization and the Purusha sukta which has great significance in Hindu social tradition. It also contains the Nasadiya sukta (10.129), probably the most celebrated hymn in the west, which deals with creation. The marriage hymns (10.85) and the death hymns (10.10-18) still are of great importance in the performance of the corresponding Grhya rituals.

Dating and historical context

The Rigveda's core is accepted to date to the late Bronze Age, making it one of the few examples with an unbroken tradition. Its composition is usually dated to roughly between 3300–1100 BC.[27] The EIEC (s.v. Indo-Iranian languages, p. 306) gives 1500–1000.[28]

Being composed in an early Indo-Aryan language, the hymns must post-date the Indo-Iranian separation, dated to roughly 2000 BC.[29] A reasonable date close to that of the composition of the core of the Rigveda is that of the Indo-Aryan Mitanni documents of c. 1400 BC.[30] Other evidence also points to a composition close to 1400 BC[31][32]

Dating using Sthapatya Veda Architecture Perhaps the most interesting evidence for the antiquity of the Vedic tradition comes from architectural remains of towns and cities of the ancient Indus-Saraswati civilization. The Indus Valley Civilization flourished, according to the most reliable current scientific estimates, between 2,600 and 1,900 BC—but there are cities, such as Mehrgarh, that date back to 6,500-7,000 BC. These dates are based on archeological fieldwork using standard methods that are commonly recognized in the scientific community today. Over 1600 settlements have been found in the vast Indus/Saraswati region that extended over 25,000 square miles.

The most well known cities of the Indus valley civilization, Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa, were built of kiln-fired brick and laid out on an exact north-south axis. This means that the main streets of the city ran north-south, and the entrance of the homes and public buildings faced east. The cities were also built to the west of the rivers, so that they were on land that sloped east to the river.

These facts, which may seem trivial on first glance, turn out to be highly significant. The ancient architectural system of Sthapatya Veda prescribes detailed principles of construction of homes and cities. One of the main principles of Sthapatya Veda is that cities be laid out on an exact north-south grid, with all houses facing due east. Another is that the buildings be oriented to the east with a slope to the east and any body of water on the east. Most of the cities of the Saraswati and Indus valley followed these principles exactly.

Astrological and Astronomical Dating [33] Several astronomers now perscribe to the dating of the Rig Veda using Astrological and mathematical formulas. The dating of the Rig Veda Archeologist Jonathan Kenoyer holds that the Indus valley script can be traced to at least 3,300 BC—making it as old or older than the oldest Sumerian written records. [34] Using astronomy as a tool to date the Rig Veda is now an accepted methodology and presents a date or origin closer to 3800 BC if not older. [35] [36]

Evidence from other sources known since the late nineteenth century also tends to confirm the great antiquity of the Vedic tradition. Certain Vedic texts, for example, refer to astronomical events that took place in ancient astronomical time.

The German scholar, H. Jacobi, came to the conclusion that the Brahmanas are from a period around or older than 4,500 BC. Jacobi concludes that “the Rig Vedic period of culture lies anterior to the third pre-Christian millennium.”[37] B. Tilak, using similar astronomical calculations, estimates the time of the Rig Veda at 6,000 BC. [38]

Professor Colin Renfrew, professor of archeology at Cambridge University, in his Archeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins, (1988) gives evidence for Indo-Europeans in India as early as 6,000 BC and comments:

"As far as I can see there is nothing in the Hymns of the Rigveda which demonstrates that the Vedic-speaking population were intrusive to the area: this comes rather from a historical assumption about the ‘coming’ of the Indo-Europeans." [39]

The Rig Veda mentions the Indus river quite often, and it mentions the Saraswati no less than 60 times. Its reference to the Saraswati as a “mighty river flowing from the mountains to the sea” shows that the Rig Vedic tradition must have been in existence long before 3,000 BC when the Saraswati ceased to be a “mighty river” and became a seasonal trickle. Frawley and Rajaram drew the conclusion that the Rig Veda must have been composed long before 3,000 BC. While the The Mahabharata, the great epic of classical Sanskrit, describes the Saraswati as a seasonal river. Since the Saraswati dried up by 1900 BC, the Mahabharata would have to be dated at least before 1,900 BC. Since it was still a seasonal river in 3,000, Rajaram and Frawley put the date of the Mahabharata in 3,000 BC. [40]

Attempts to date the Rig Veda based on astronomical evidence have great merit, but the conclusions are hotly debated, and probably not entirely free of conjecture since there has been a bias from a western mindset and an opposing view correlating using astronomy and religious texts. Several contemporary scholars however take them quite seriously as a method of dating the Rig Veda. Philological The Rigveda is far more archaic than any other Indo-Aryan text. For this reason, it was in the center of attention of western scholarship from the times of Max Müller and Rudolf Roth onwards. The Rigveda records an early stage of Vedic religion. There are strong linguistic and cultural similarities with the early Iranian Avesta,[41] deriving from the Proto-Indo-Iranian times,[42][43] often associated with the early Andronovo culture of ca. 2000 BC.[44]

The text in the following centuries underwent pronunciation revisions and standardization (samhitapatha, padapatha). This redaction would have been completed around the 6th century BC.[45] Exact dates are not established, but they fall within the pre-Buddhist period (500, or rather 400 BC).

Writing appears in India around the 3rd century BC in the form of the Brahmi script, but texts of the length of the Rigveda were likely not written down until much later, the oldest surviving Rigvedic manuscript dating to the 14th century. While written manuscripts were used for teaching in medieval times, they were written on birch bark or palm leaves, which decompose fairly quickly in the tropical climate, until the advent of the printing press from the 16th century. Some Rigveda commentaries may date from the second half of the first millennium CE. The hymns were thus preserved by oral tradition for up to a millennium from the time of their composition until the redaction of the Rigveda, and the entire Rigveda was preserved in shakhas for another 2,500 years from the time of its redaction until the editio princeps by Rosen, Aufrecht and Max Müller.

After their composition, the texts were preserved and codified by an extensive body of Vedic priesthood as the central philosophy of the Iron Age Vedic civilization. The Brahma Purana and the Vayu Purana name one Vidagdha as the author of the Padapatha.[46] The Rk-pratishakhya names Sthavira Shakalya of the Aitareya Aranyaka as its author.[47]

Summary The Rigveda describes a mobile, semi-nomadic culture, with horse-drawn chariots, oxen-drawn wagons, and metal (bronze) weapons. The geography described is consistent with that of the Greater Punjab: Rivers flow north to south, the mountains are relatively remote but still visible and reachable (Soma is a plant found in the high mountains, and it has to be purchased from tribal people). Nevertheless, the hymns were certainly composed over a long period, with the oldest (not preserved) elements possibly reaching back to times close to the split of Proto-Indo-Iranian (around 2000 BC)[48] Thus there was some debate over whether the boasts of the destruction of stone forts by the Vedic Aryans and particularly by Indra refer to cities of the Indus Valley civilization or whether they rather hark back to clashes between the early Indo-Aryans with the BMAC in what is now northern Afghanistan and southern Turkmenistan (separated from the upper Indus by the Hindu Kush mountain range, and some 400 km distant).

While it is highly likely that the bulk of the Rigvedic hymns were composed in the Punjab, even if based on earlier poetic traditions, there is no mention of either tigers or rice[49] in the Rigveda (as opposed to the later Vedas), suggesting that Vedic culture only penetrated into the plains of India after its completion. Similarly, there is no mention of iron as the term ayas occurring in the Rig Veda refers to useful metal in general.[50] The "black metal" (kṛṣṇa ayas) is first mentioned in the post-Rigvedic texts (Atharvaveda etc.). The Iron Age in northern India begins in the 10th century in the Greater Panjab. There is a widely accepted timeframe for the beginning codification of the Rigveda by compiling the hymns very late in the Rigvedic or rather in the early post-Rigvedic period, including the arrangement of the individual hymns in ten books, coeval with and the composition of the younger Veda Samhitas. This time coincides with the early Kuru kingdom, shifting the center of Vedic culture east from the Punjab into what is now Uttar Pradesh. The fixing of the samhitapatha (by keeping Sandhi) intact and of the padapatha (by dissolving Sandhi out of the earlier metrical text), occurred during the later Brahmana period.

Some of the names of gods and goddesses found in the Rigveda are found amongst other belief systems based on Proto-Indo-European religion, while words used share common roots with words from other Indo-European languages.

The horse (ashva), cattle, sheep and goat play an important role in the Rigveda. There are also references to the elephant (Hastin, Varana), camel (Ustra, especially in Mandala 8), ass (khara, rasabha), buffalo (Mahisa), wolf, hyena, lion (Simha), mountain goat (sarabha) and to the gaur in the Rigveda.[51] The peafowl (mayura), the goose (hamsa) and the chakravaka (Anas casarca) are some birds mentioned in the Rigveda.

Ancillary Texts

Rigveda Brahmanas

Of the Brahmanas that were handed down in the schools of the Bahvṛcas (i.e. "possessed of many verses"), as the followers of the Rigveda are called, two have come down to us, namely those of the Aitareyins and the Kaushitakins. The Aitareya-brahmana[52] and the Kaushitaki- (or Sankhayana-) brahmana evidently have for their groundwork the same stock of traditional exegetic matter. They differ, however, considerably as regards both the arrangement of this matter and their stylistic handling of it, with the exception of the numerous legends common to both, in which the discrepancy is comparatively slight. There is also a certain amount of material peculiar to each of them.

The Kaushitaka is, upon the whole, far more concise in its style and more systematic in its arrangement features which would lead one to infer that it is probably the more modern work of the two. It consists of thirty chapters (adhyaya); while the Aitareya has forty, divided into eight books (or pentads, pancaka), of five chapters each. The last ten adhyayas of the latter work are, however, clearly a later addition though they must have already formed part of it at the time of Pāṇini (ca. 5th c. BC), if, as seems probable, one of his grammatical sutras, regulating the formation of the names of Brahmanas, consisting of thirty and forty adhyayas, refers to these two works. In this last portion occurs the well-known legend (also found in the Shankhayana-sutra, but not in the Kaushitaki-brahmana) of Shunahshepa, whom his father Ajigarta sells and offers to slay, the recital of which formed part of the inauguration of kings.

While the Aitareya deals almost exclusively with the Soma sacrifice, the Kaushitaka, in its first six chapters, treats of the several kinds of haviryajna, or offerings of rice, milk, ghee, &c., whereupon follows the Soma sacrifice in this way, that chapters 7-10 contain the practical ceremonial and 11-30 the recitations (shastra) of the hotar. Sayana, in the introduction to his commentary on the work, ascribes the Aitareya to the sage Mahidasa Aitareya (i.e. son of Itara), also mentioned elsewhere as a philosopher; and it seems likely enough that this person arranged the Brahmana and founded the school of the Aitareyins. Regarding the authorship of the sister work we have no information, except that the opinion of the sage Kaushitaki is frequently referred to in it as authoritative, and generally in opposition to the Paingya—the Brahmana, it would seem, of a rival school, the Paingins. Probably, therefore, it is just what one of the manuscripts calls it—the Brahmana of Sankhayana (composed) in accordance with the views of Kaushitaki.

Rigveda Aranyakas

Each of these two Brahmanas is supplemented by a "forest book", or Aranyaka. The Aitareyaranyaka is not a uniform production. It consists of five books (aranyaka), three of which, the first and the last two, are of a liturgical nature, treating of the ceremony called mahavrata, or great vow. The last of these books, composed in sutra form, is, however, doubtless of later origin, and is, indeed, ascribed by Hindu authorities either to Shaunaka or to Ashvalayana. The second and third books, on the other hand, are purely speculative, and are also styled the Bahvrca-brahmana-upanishad. Again, the last four chapters of the second book are usually singled out as the Aitareyopanishad, ascribed, like its Brahmana (and the first book), to Mahidasa Aitareya; and the third book is also referred to as the Samhita-upanishad. As regards the Kaushitaki-aranyaka, this work consists of 15 adhyayas, the first two (treating of the mahavrata ceremony) and the 7th and 8th of which correspond to the 1st, 5th, and 3rd books of the Aitareyaranyaka, respectively, whilst the four adhyayas usually inserted between them constitute the highly interesting Kaushitaki (brahmana-) upanishad, of which we possess two different recensions. The remaining portions (9-15) of the Aranyaka treat of the vital airs, the internal Agnihotra, etc., ending with the vamsha, or succession of teachers.

Medieval Hindu scholarship

According to Hindu tradition, the Rigvedic hymns were collected by Paila under the guidance of Vyāsa, who formed the Rigveda Samhita as we know it. According to the Śatapatha Brāhmana, the number of syllables in the Rigveda is 432,000, equalling the number of muhurtas (1 day = 30 muhurtas) in forty years. This statement stresses the underlying philosophy of the Vedic books that there is a connection (bandhu) between the astronomical, the physiological, and the spiritual.

The authors of the Brāhmana literature discussed and interpreted the Vedic ritual. Yaska was an early commentator of the Rigveda by discussing the meanings of difficult words. In the 14th century, Sāyana wrote an exhaustive commentary on it.

A number of other commentaries bhāṣyas were written during the medieval period, including the commentaries by Skandasvamin (pre-Sayana, roughly of the Gupta period), Udgitha (pre-Sayana), Venkata-Madhava (pre-Sayana, ca. 10th to 12th century) and Mudgala (after Sayana, an abbreviated version of Sayana's commentary).[53]

In contemporary Hinduism

Hindu revivalism

Since the 19th and 20th centuries, some reformers like Swami Dayananda, founder of the Arya Samaj and Sri Aurobindo have attempted to re-interpret the Vedas to conform to modern and established moral and spiritual norms. Dayananda considered the Vedas (which he defined to include only the samhitas) to be source of truth, totally free of error and containing the seeds of all valid knowledge. Contrary to common understanding, he was adamant that Vedas were monotheistic and that they did not sanction idol worship.[54] Starting 1877, he intended to publish commentary on the four vedas but completed work on only the Yajurveda, and a partial commentary on the Rigveda. Dayananda's work is not highly regarded by Vedic scholars and Indologist Louis Renou, among others, dismissed it as, "a vigorous (and from our point of view, extremely aberrant) interpretation in the social and political sense."[55][56]

Dayananda and Aurobindo moved the Vedantic perception of the Rigveda from the original ritualistic content to a more symbolic or mystical interpretation. For example, instances of animal sacrifice were not seen by them as literal slaughtering, but as transcendental processes.

"Indigenous Aryans" debate

Questions surrounding the Rigvedic Sarasvati river and the Nadistuti sukta in particular have become tied to an ideological debate on the Indo-Aryan migration (termed "Aryan Invasion Theory") vs. the claim that Vedic culture together with Vedic Sanskrit originated in the Indus Valley Civilisation (termed "Out of India theory"), a topic of great significance in Hindu nationalism, addressed for example by Amal Kiran and Shrikant G. Talageri. Subhash Kak (1994) claimed that there is an "astronomical code" in the organization of the hymns. Bal Gangadhar Tilak, also based on astronomical alignments in the Rigveda, in his "The Orion" (1893) had claimed presence of the Rigvedic culture in India in the 4th millennium BC, and in his "Arctic Home in the Vedas" (1903) even argued that the Aryans originated near the North Pole and came south during the Ice Age.

Debate on alternative suggestions on the date of the Rigveda, typically much earlier dates, are mostly taking place outside of scholarly literature. Some writers out of the mainstream claim to trace astronomical references in the Rigveda, dating it to as early as 4000 BC,[57] a date well within the Indian Neolithic.[58]. Publications to this effect have increased during the late 1990s to early 2000s in the context of historical revisionism in Hindu nationalism, notably in books published by Voice of India.[59]

Translations

The first published translation of any portion of the Rigveda in any Western language was into Latin, by Friedrich August Rosen (Rigvedae specimen, London 1830). Predating Müller's editio princeps of the text, Rosen was working from manuscripts brought back from India by Colebrooke.

H. H. Wilson was the first to make a complete translation of the Rig Veda into English, published in six volumes during the period 1850-88.[60] Wilson's version was based on the commentary of Sāyaṇa. In 1977, Wilson's edition was enlarged by Nag Sharan Singh (Nag Publishers, Delhi, 2nd ed. 1990).

In 1889, Ralph T.H. Griffith published his translation as The Hymns of the Rig Veda, published in London (1889).[61]

A German translation was published by Karl Friedrich Geldner, Der Rig-Veda: aus dem Sanskrit ins Deutsche Übersetzt, Harvard Oriental Studies, vols. 33–37 (Cambridge, Massachusetts: 1951-7).[62]

Geldner's translation was the philologically best-informed to date, and a Russian translation based on Geldner's by Tatyana Elizarenkova was published by Nauka 1989-1999[63]

A 2001 revised edition of Wilson's translation was published by Ravi Prakash Arya and K. L. Joshi.[64] The revised edition updates Wilson's translation by replacing obsolete English forms with more modern equivalents, giving the English translation along with the original Sanskrit text in Devanagari script, along with a critical apparatus.

In 2004 the United States' National Endowment for the Humanities funded Joel Brereton and Stephanie W. Jamison as project directors for a new original translation to be issued by Oxford University Press.[65][66]

Numerous partial translations exist into various languages. Notable examples include:

- A. A. Macdonell. Hymns from the Rigveda (Calcutta, London, 1922); A Vedic Reader for Students (Oxford, 1917).

- French: A. Langlois, Rig-véda, ou livre des hymnes, Paris 1948-51 ISBN 2-7200-1029-4

- Hungarian: Laszlo Forizs, Rigvéda - Teremtéshimnuszok (Creation Hymns of the Rig-Veda), Budapest, 1995 ISBN 963-85349-1-5 Hymns of the Rig-Veda

- Wendy Doniger O'Flaherty issued a modern selection with a translation of 108 hymns, along with critical apparatus. A bibliography of translations of the Rig Veda appears as an Appendix that work.[67]

- A new German translations of books 1 and 2 was presented in 2007 by Michael Witzel and Toshifumi Goto (ISBN 978-3-458-70001-2 / ISBN 978-3-458-70001-3).

- A partial Hindi translation by Govind Chandra Pande was published in 2008 (by Lokbharti Booksellers and Distributors, Allahabad, covering books 3-5).

Notes

- ↑ derived from the root ṛc "to praise", cf. Dhātupātha 28.19. Monier-Williams translates "a Veda of Praise or Hymn-Veda"

- ↑ There is some confusion with the term "Veda", which is traditionally applied to the texts associated with the samhita proper, such as Brahmanas or Upanishads. In English usage, the term Rigveda is usually used to refer to the Rigveda samhita alone, and texts like the Aitareya-Brahmana are not considered "part of the Rigveda" but rather "associated with the Rigveda" in the tradition of a certain shakha.

- ↑ most popularly the Gayatri mantra of RV 3. Brodd, Jefferey (2003). World Religions. Winona, Minnesota: Saint Mary's Press. ISBN 978-0-88489-725-5.

- ↑ Oberlies (1998:155) gives an estimate of 1100 BC for the youngest hymns in book 10. Estimates for a terminus post quem of the earliest hymns are more uncertain. Oberlies (p. 158) based on 'cumulative evidence' sets wide range of 1700–1100.

- ↑ Rig Veda, verses 1.117.22, 1.116.12, 1.84.13.5.

- ↑ .See Jonnathan Mark Kenoyer, “Birth of a Civilization.” Archeology, January/February 1998, 54-61, p. 61.

- ↑ J. Norman Lockyer, The Dawn of Astronomy, MIT Press, 1894.

- ↑ Ancient calendars and constellations By Emmeline Mary Plunket

- ↑ Colin Renfrew, Professor of Archeology at Cambridge University, in his famous work, Archeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988) Renfrew also sees evidence that the Indo-Europeans were in Greece as early as 6,000 BC.

- ↑ H. Oldenberg, Prolegomena,1888, Engl. transl. New Delhi: Motilal 2004

- ↑ K. Meenakshi (2002). "Making of Pāṇini". In George Cardona, Madhav Deshpande, Peter Edwin Hook. Indian Linguistic Studies: Festschrift in Honor of George Cardona. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 235. ISBN 8120818857.

- ↑ The oldest manuscript in the Pune collection dates to the 15th century. The Benares Sanskrit University has a Rigveda manuscript of the 14th century. Earlier manuscripts are extremely rare; the oldest known manuscript preserving a Vedic text was written in the 11th century in Nepal (catalogued by the Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project, Hamburg.

- ↑ B. van Nooten and G. Holland, Rig Veda. A metrically restored text. Cambridge: Harvard Oriental Series 1994

- ↑ Michael Witzel says that "The RV has been transmitted in one recension (the śākhā of Śākalya) while others (such as the Bāṣkala text) have been lost or are only rumored about so far." Michael Witzel, p. 69, "Vedas and Upaniṣads", in: The Blackwell Companion to Hinduism, Gavin Flood (ed.), Blackwell Publishing Ltd., 2005.

- ↑ Maurice Winternitz (History of Sanskrit Literature, Revised English Translation Edition, 1926, vol. 1, p. 57) says that "Of the different recensions of this Saṃhitā, which once existed, only a single one has come down to us." He adds in a note (p. 57, note 1) that this refers to the "recension of the Śākalaka-School."

- ↑ Sures Chandra Banerji (A Companion To Sanskrit Literature, Second Edition, 1989, Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, pp. 300-301) says that "Of the 21 recensions of this Veda, that were known at one time, we have got only two, viz. Śākala and Vāṣkala."

- ↑ Maurice Winternitz (History of Sanskrit Literature, Revised English Translation Edition, 1926, vol. 1, p. 283.

- ↑ Mantras of "khila" hymns were called khailika and not ṛcas (Khila meant distinct "part" of Rgveda separate from regular hymns; all regular hymns make up the akhila or "the whole" recognised in a śākhā, although khila hymns have sanctified roles in rituals from ancient times).

- ↑ Hermann Grassmann had numbered the hymns 1 through to 1028, putting the vālakhilya at the end. Griffith's translation has these 11 at the end of the 8th mandala, after 8.92 in the regular series.

- ↑ cf. Preface to Khila section by C.G.Kāshikar in Volume-5 of Pune Edition of RV (in references).

- ↑ These Khilani hymns have also been found in a manuscript of the Śākala recension of the Kashmir Rigveda (and are included in the Poone edition).

- ↑ equalling 40 times 10,800, the number of bricks used for the uttaravedi: the number is motivated numerologically rather than based on an actual syllable count.

- ↑ In a few cases, more than one rishi is given, signifying lack of certainty.

- ↑ Talageri (2000), p.33

- ↑ http://hinduism.about.com/od/scripturesepics/a/rigveda.htm

- ↑ cf. Editorial notes in various volumes of Pune Edition, see references.

- ↑ Oberlies (1998:155) gives an estimate of 1100 BC for the youngest hymns in book 10. Estimates for a terminus post quem of the earliest hymns are far more uncertain. Oberlies (p. 158) based on 'cumulative evidence' sets wide range of 1700–1100

- ↑ Philological estimates tend to date the bulk of the text to the second half of the second millennium. Compare Max Müller's statement "the hymns of the Rig-Veda are said to date from 1500 BC" ('Veda and Vedanta', 7th lecture in India: What Can It Teach Us: A Course of Lectures Delivered Before the University of Cambridge, World Treasures of the Library of Congress Beginnings by Irene U. Chambers, Michael S. Roth.

- ↑ Mallory, J. P.; Adams, Douglas Q. (1997). "Indo-Iranian Languages". Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Fitzroy Dearborn.

- ↑ "As a possible date ad quem for the RV one usually adduces the Hittite-Mitanni agreement of the middle of the 14th cent. B.C. which mentions four of the major Rgvedic gods: mitra, varuNa, indra and the nAsatya azvin)" M. Witzel, Early Sanskritization - Origin and development of the Kuru state.

- ↑ The Vedic People: Their History and Geography, Rajesh Kochar, 2000, Orient Longman, ISBN 8125013849

- ↑ Rigveda and River Saraswati: http://www.class.uidaho.edu/ngier/306/contrasarav.htm

- ↑ Rig Veda, verses 1.117.22, 1.116.12, 1.84.13.5.

- ↑ .See Jonnathan Mark Kenoyer, “Birth of a Civilization.” Archeology, January/February 1998, 54-61, p. 61.

- ↑ J. Norman Lockyer, The Dawn of Astronomy, MIT Press, 1894.

- ↑ Ancient calendars and constellations By Emmeline Mary Plunket

- ↑ Maurice Winternitz, A History of Vedic Literature, Vol. 1, p. 277.

- ↑ B.G. Tilak, The Orion, or Researches into the Antiquity of the Vedas (Bombay: 1893).

- ↑ Colin Renfrew, Professor of Archeology at Cambridge University, in his famous work, Archeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1988) Renfrew also sees evidence that the Indo-Europeans were in Greece as early as 6,000 BC.

- ↑ N.S. Rajaram, Hindustan Times. N.S. Rajaram, Aryan Invasion of India: The Myth and the Truth.

- ↑ Oldenberg 1894 (tr. Shrotri), p.14 "The Vedic diction has a great number of favourite expressions which are common with the Avestic, though not with later Indian diction. In addition, there is a close resemblance between them in metrical form, in fact, in their overall poetic character. If it is noticed that whole Avesta verses can be easily translated into the Vedic alone by virtue of comparative phonetics, then this may often give, not only correct Vedic words and phrases, but also the verses, out of which the soul of Vedic poetry appears to speak."

- ↑ Mallory 1989 p.36 "Probably the least-contested observation concerning the various Indo-European dialects is that those languages grouped together as Indic and Iranian show such remarkable similarities with one another that we can confidently posit a period of Indo-Iranian unity..."

- ↑ Bryant 2001:130–131 "The oldest part of the Avesta... is linguistically and culturally very close to the material preserved in the Rgveda... There seems to be economic and religious interaction and perhaps rivalry operating here, which justifies scholars in placing the Vedic and Avestan worlds in close chronological, geographical and cultural proximity to each other not far removed from a joint Indo-Iranian period."

- ↑ Mallory 1989 "The identification of the Andronovo culure as Indo-Iranian is commonly accepted by scholars."

- ↑ Oldenberg (p. 379) places it near the end of the Brahmana period, seeing that the older Brahmanas still contain pre-normalized Rigvedic citations. The Brahmana period is later than the composition of the samhitas of the other Vedas, stretching for about the 10th to 6th centuries. This would mean that the redaction of the texts as preserved was completed in roughly the 6th century BC. The EIEC (p. 306) gives a 7th century date.

- ↑ . The Shatapatha Brahmana refers to a Vidagdha Shakalya without discussing anything related to the Padapatha.

- ↑ Jha 1992

- ↑ minority opinions name dates as early as the 4th millennium BC; "The Aryan Non-Invasionist Model" by Koenraad Elst

- ↑ There is however mention of ApUpa, Puro-das and Odana in the Rigveda, terms that, at least in later texts, refer to rice dishes, see Talageri (2000)

- ↑ The term "ayas" (=metal) occurs in the Rigveda, usually translated as "bronze", although Chakrabarti, D.K. The Early Use of Iron in India (1992) Oxford University Press argues that it may refer to any metal. If ayas refers to iron, the Rigveda must date to the late 2nd millennium at the earliest.

- ↑ among others, Macdonell and Keith, and Talageri 2000, Lal 2005

- ↑ Edited, with an English translation, by M. Haug (2 vols., Bombay, 1863). An edition in Roman transliteration, with extracts from the commentary, has been published by Th. Aufrecht (Bonn, 1879).

- ↑ edited in 8 volumes by Vishva Bandhu, 1963-1966.

- ↑ Salmond, Noel A. (2004). "Dayananda Saraswati". Hindu iconoclasts: Rammohun Roy, Dayananda Sarasvati and nineteenth-century polemics against idolatry. Wilfrid Laurier University Press. pp. 65–91. ISBN 0-88920-419-5.

- ↑ Llewellwyn, John (1994). "From interpretation to reform: Dayanand's reading of the Vedas". In Patton, Laurie L.. Authority, anxiety, and canon: essays in Vedic interpretation. Albany, N.Y: State University of New York Press. pp. 235–252. ISBN 0-7914-1937-1.

- ↑ Renou, Louis (1965). The destiny of the Veda in India. Motilal Banarsidas. p. 4.

- ↑ summarized by Klaus Klostermaier in a 1998 presentation

- ↑ e.g. Michael Witzel, The Pleiades and the Bears viewed from inside the Vedic texts, EVJS Vol. 5 (1999), issue 2 (December) [1]; Elst, Koenraad (1999). Update on the Aryan Invasion Debate. Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-86471-77-4.; Bryant, Edwin and Laurie L. Patton (2005) The Indo-Aryan Controversy, Routledge/Curzon.

- ↑ they reached a peak when the academic Journal of Indo-European Studies waived peer-review in a 2002 issue in order to give a platform to the views of N. Kazanas, suggests a date as early as 3100 BC. The journal's editor J. P. Mallory described this exceptional issue as motivated by a "sense of fair play". The debate consisted of an article by Kazanas, nine highly critical reviews by referees published in reply and a "final response" by Kazanas (Journal of Indo-European Studies 30, 2002. Journal of Indo-European Studies 31, 2003)

- ↑ Wilson, H. H. Ṛig-Veda-Sanhitā: A Collection of Ancient Hindu Hymns. 6 vols. (London, 1850-88); repring: Cosmo Publications (1977)

- ↑ reprinted Delhi 1973, reprinted by Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers: 1999. Complete revised and enlarged edition. 2-volume set. ISBN 8121500419

- ↑ reprint: Harvard Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies Harvard (University Press) (2003) ISBN 0-674-01226-7

- ↑ extended from a partial translation Rigveda: Izbrannye Gimny, published in 1972.

- ↑ Ravi Prakash Arya and K. L. Joshi. Ṛgveda Saṃhitā: Sanskrit Text, English Translation, Notes & Index of Verses. (Parimal Publications: Delhi, 2001) ISBN 81-7110-138-7 (Set of four volumes). Parimal Sanskrit Series No. 45; 2003 reprint: 81-7020-070-9

- ↑ http://www.neh.gov/news/awards/collaborative2004.html retrieved 22 March 2007.

- ↑ Joel Brereton and Stephanie W. Jamison. The Rig Veda: Translation and Explanatory Notes. (Oxford University Press) ISBN 0195179188

- ↑ See Appendix 3, O'Flaherty, Wendy Doniger. The Rig Veda. (Penguin Books: 1981) ISBN 0-140-44989-2

Bibliography

- Editions

- editio princeps: Friedrich Max Müller, The Hymns of the Rigveda, with Sayana's commentary, London, 1849–75, 6 vols., 2nd ed. 4 vols., Oxford, 1890–92.

- Theodor Aufrecht, 2nd ed., Bonn, 1877.

- Sontakke, N. S., ed (1933-46,Reprint 1972-1983.). Rgveda-Samhitā: Śrimat-Sāyanāchārya virachita-bhāṣya-sametā (First ed.). Pune: Vaidika Samśodhana Maṇḍala. The Editorial Board for the First Edition included N. S. Sontakke (Managing Editor), V. K. Rājvade, M. M. Vāsudevaśāstri, and T. S. Varadarājaśarmā.

- B. van Nooten und G. Holland, Rig Veda, a metrically restored text, Department of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England, 1994.

- Rgveda-Samhita, Text in Devanagari, English translation Notes and indices by H. H. Wilson, Ed. W.F. Webster, originally in 1888, Published Nag Publishers 1990, 11A/U.A. Jawaharnagar,Delhi-7.

- Commentary

- Sayana (14th century)

- ed. Müller 1849-75 (German translation);

- ed. Müller (original commentary of Sāyana in Sanskrit based on 24 manuscripts).

- ed. Sontakke et al., published by Vaidika Samsodhana Mandala, Pune (2nd ed. 1972) in 5 volumes.

- Rgveda-Samhitā Srimat-sāyanāchārya virachita-bhāṣya-sametā, ed. by Sontakke et al., published by Vaidika Samśodhana Mandala,Pune-9,1972 ,in 5 volumes (It is original commentary of Sāyana in Sanskrit based on over 60 manuscripts).

- Sri Aurobindo: Hymns to the Mystic Fire (Commentary on the Rig Veda), Lotus Press, Twin Lakes, Wisconsin ISBN 0-914955-22-5 [2]

- Philology

- Vashishtha Narayan Jha, A Linguistic Analysis of the Rgveda-Padapatha Sri Satguru Publications, Delhi (1992).

- Bjorn Merker, Rig Veda Riddles In Nomad Perspective, Mongolian Studies, Journal of the Mongolian Society XI, 1988.

- Thomas Oberlies, Die Religion des Rgveda, Wien 1998.

- Oldenberg, Hermann: Hymnen des Rigveda. 1. Teil: Metrische und textgeschichtliche Prolegomena. Berlin 1888; Wiesbaden 1982.

- —Die Religion des Veda. Berlin 1894; Stuttgart 1917; Stuttgart 1927; Darmstadt 1977

- —Vedic Hymns, The Sacred Books of the East vo, l. 46 ed. Friedrich Max Müller, Oxford 1897

- Adolf Kaegi, The Rigveda: The Oldest Literature of the Indians (trans. R. Arrowsmith), Boston,, Ginn and Co. (1886), 2004 reprint: ISBN 9781417982059.

- Historical

- Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195137779

- Lal, B.B. 2005. The Homeland of the Aryans. Evidence of Rigvedic Flora and Fauna & Archaeology, New Delhi, Aryan Books International.

- Talageri, Shrikant: The Rigveda: A Historical Analysis, 2000. ISBN 81-7742-010-0

- Archaeoastronomy

- Tilak, Bal Gangadhar: The Orion, 1893.

See also

External links

- Rigveda - Nominations submitted by India in 2006-2007 for inclusion in the Memory of the World Register. (.doc format)

- Text

- Devanagari and transliteration experimental online text at: sacred-texts.com

- ITRANS, Devanagari, transliteration online text and PDF, several versions prepared by Detlef Eichler

- Transliteration with tone accents PDF prepared by Keith Briggs

- Transliteration, metrically restored online text, at: Linguistics Research Center, Univ. of Texas

- The Hymns of the Rigveda by Friedrich Max Müller large PDF files of book scans. Two editions: London, 1877 (Samhita and Pada texts) and Oxford, 1890–92, with Sayana's commentary.

- Audio download MP3, chanted in North Indian style, i.e. without tones (yeha swara) at: gatewayforindia.com

- Translation

- The Rig Veda 1895, by Ralph Griffith (sacred-texts.com)

- Rig-Veda Sanhita: A Collection of Ancient Hindu Hymns by H. H. Wilson (Scroll a little down.)

|

||||||||||||||