Rhinoceros

| Rhinoceros Fossil range: Eocene–Recent |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Black Rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) in Tanzania. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Rhinocerotidae Gray, 1820 |

| Extant Genera | |

|

Ceratotherium |

|

Rhinoceros (pronounced /raɪˈnɒsərəs/) – Greek ῥῑνόκερως – often colloquially abbreviated rhino, is a group of five extant species of odd-toed ungulates in the family rhinocerotidae. Two of these species are native to Africa and three to southern Asia.

The rhinoceros family is characterized by its large size (one of the largest remaining megafauna), with all of the species able to reach one ton or more in weight; an herbivorous diet; and a thick protective skin, 1.5–5 cm thick, formed from layers of collagen positioned in a lattice structure; relatively small brains for mammals this size (400–600 g); and a large horn. They generally eat leafy material, although their ability to ferment food in their hindgut allows them to subsist on more fibrous plant matter, if necessary. Unlike other perissodactyls, the African species of rhinoceros lack teeth at the front of their mouths, relying instead on their powerful premolar and molar teeth to grind up plant food.[1]

Rhinoceros are killed by humans for their valuable horns, which are made of keratin, the same type of protein that makes up hair and fingernails.[2] Both African species and the Sumatran Rhinoceros have two horns, while the Indian and Javan Rhinoceros have a single horn. Rhinoceros have acute hearing and sense of smell, but poor eyesight. Most live to be about 60 years old or more.

The IUCN Red List identifies three of the species as "critically endangered".

Contents |

Taxonomy and naming

The word rhinoceros is derived through Latin from the Greek ῥῑνόκερως, which is composed of ῥῑνο-, ῥίς (rhino-, rhis), meaning nose, and κέρας (keras), meaning horn. The plural in English is rhinoceros or rhinoceroses. The collective noun for a group of rhinoceros is crash or herd.[3]

The five living species fall into three categories. The two African species, the White Rhinoceros and the Black Rhinoceros, diverged during the early Pliocene (about 5 million years ago) but the Dicerotini group to which they belong originated in the middle Miocene, about 14.2 million years ago. The main difference between black and white rhinos is the shape of their mouths. White rhinos have broad flat lips for grazing and black rhinos have long pointed lips for eating foliage. A popular — if unverified — theory claims that the name White Rhinoceros was actually a mistake, or rather a corruption of the word wyd ("wide" in Afrikaans), referring to their square lips.[4]

White Rhinoceros are divided into Northern and Southern subspecies. There are two living Rhinocerotini species, the Indian Rhinoceros and the Javan Rhinoceros, which diverged from one another about 10 million years ago. The Sumatran Rhinoceros is the only surviving representative of the most primitive group, the Dicerorhinini, which emerged in the Miocene (about 20 million years ago).[5] The extinct Woolly Rhinoceros of northern Europe and Asia was also a member of this tribe.

A subspecific hybrid white rhino (Ceratotherium s. simum × C. s. cottoni) was bred at the Dvůr Králové Zoo (Zoological Garden Dvur Kralove nad Labem) in the Czech Republic in 1977. Interspecific hybridisation of Black and White Rhinoceros has also been confirmed.[6]

All rhinoceros species have 82 chromosomes (diploid number, 2N, per cell), except the Black Rhinoceros, which has 84. This is the highest known chromosome number of all mammals.

White Rhinoceros

The White or Square-lipped Rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum) is, after the elephant, the most massive remaining land animal in the world, along with the Indian Rhinoceros and the hippopotamus, which are of comparable size. There are two subspecies of White Rhinos; as of 2005, South Africa has the most of the first subspecies, the Southern White Rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum simum). The population of Southern White Rhinos is about 14,500, making them the most abundant subspecies of rhino in the world. However, the population of the second subspecies, the critically endangered Northern White Rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum cottoni), is down to as few as four individuals in the wild, and as of June 2008 this sub-species are thought to have become extinct in the wild.[7]. Six are known to be held in captivity, two of which reside in a zoo in San Diego. There are currently four that were in held in captivity since 1982 in a zoo in the Czech Republic which were transferred to a wildlife refuge in Kenya in December 2009, in an effort have the animals reproduce and save the subspecies[8].

The White Rhino has an immense body and large head, a short neck and broad chest. This rhino can exceed 3,500 kg (7,700 lb), have a head-and-body length of 3.5–4.6 m (11–15 ft) and a shoulder height of 1.8–2 m (5.9–6.6 ft) The record-sized White Rhinoceros was about 4,600 kg (10,000 lb).[9] On its snout it has two horns. The front horn is larger than the other horn and averages 90 cm (35 in) in length and can reach 150 cm (59 in). The White Rhinoceros also has a prominent muscular hump that supports its relatively large head. The colour of this animal can range from yellowish brown to slate grey. Most of its body hair is found on the ear fringes and tail bristles with the rest distributed rather sparsely over the rest of the body. White Rhinos have the distinctive flat broad mouth which is used for grazing.

Black Rhinoceros

The name Black Rhinoceros (Diceros bicornis) was chosen to distinguish this species from the White Rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum). This can be confusing, as those two species are not really distinguishable by colour. There are four subspecies of black rhino: South-central (Diceros bicornis minor), the most numerous, which once ranged from central Tanzania south through Zambia, Zimbabwe and Mozambique to northern and eastern South Africa; South-western (Diceros bicornis bicornis) which are better adapted to the arid and semi-arid savannas of Namibia, southern Angola, western Botswana and western South Africa; East African (Diceros bicornis michaeli), primarily in Tanzania; and West African (Diceros bicornis longipes) which was tentatively declared extinct in 2006.[10]

An adult Black Rhinoceros stands 150–175 cm (59–69 in) high at the shoulder and is 3.5–3.9 m (11–13 ft) in length.[11] An adult weighs from 850 to 1,600 kg (1,900 to 3,500 lb), exceptionally to 1,800 kg (4,000 lb), with the females being smaller than the males. Two horns on the skull are made of keratin with the larger front horn typically 50 cm long, exceptionally up to 140 cm. Sometimes, a third smaller horn may develop. The Black Rhino is much smaller than the White Rhino, and has a pointed mouth, which they use to grasp leaves and twigs when feeding.

Indian Rhinoceros

The Indian Rhinoceros or the Great One-horned Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros unicornis) is now found almost exclusively in Nepal and North-Eastern India. The rhino once inhabited many areas of Pakistan to Burma and may have even roamed in China. But because of human influence their range has shrunk and now they only exist in several protected areas of India (in Assam, West Bengal and a few pairs in Uttar Pradesh) and Nepal, plus a few pairs in Lal Suhanra national park in Pakistan. It is confined to the tall grasslands and forests in the foothills of the Himalayas.

The Indian Rhinoceros has thick, silver-brown skin which creates huge folds all over its body. Its upper legs and shoulders are covered in wart-like bumps, and it has very little body hair. Fully grown males are larger than females in the wild, weighing from 2,500–3,200 kg (5,500–7,100 lb).The Indian rhino stands at 1.75-2.0 meters (5.75-6.5 ft) Female Indian rhinos weigh about 1,900 kg. The Indian Rhino is from 3–4 metres long. The record-sized specimen of this rhino was approximately 3,800 kg. The Indian Rhino has a single horn that reaches a length of between 20 and 100 cm. Its size is comparable to that of the White Rhino in Africa.

Two-thirds of the world's Great One-horned Rhinoceroses are now confined to the Kaziranga National Park situated in the Golaghat district of Assam, India.[12]

Javan Rhinoceros

The Javan Rhinoceros (Rhinoceros sondaicus) is one of the rarest and most endangered large mammals anywhere in the world.[13] According to 2002 estimates, only about 60 remain, in Java (Indonesia) and Vietnam. Of all the rhino species, the least is known of the Javan Rhino. These animals prefer dense lowland rain forest, tall grass and reed beds that are plentiful with large floodplains and mud wallows. Though once widespread throughout Asia, by the 1930s the rhinoceros was nearly hunted to extinction in India, Burma, Peninsular Malaysia, and Sumatra for the supposed medical powers of its horn and blood. As of 2009, there are only 40 of them remaining in Ujung Kulon Conservation, Java, Indonesia.

Like the closely related larger Indian Rhinoceros, the Javan rhinoceros has only a single horn. Its hairless, hazy gray skin falls into folds into the shoulder, back, and rump giving it an armored-like appearance. The Javan rhino's body length reaches up to 3.1–3.2 m (10–10 ft), including its head and a height of 1.5–1.7 m (4 ft 10 in–5 ft 7 in) tall. Adults are variously reported to weigh between 900–1,400 kg[14] or 1,360-2,000 kg.[15] Male horns can reach 26 cm in length while in females they are knobs or are not present at all.[15]

Sumatran Rhinoceros

The Sumatran Rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) is the smallest extant rhinoceros species, as well as the one with the most fur, which allows it to survive at very high altitudes in Borneo and Sumatra. Due to habitat loss and poaching, its numbers have declined and it is one of the world's rarest mammals. About 275 Sumatran Rhinos are believed to remain.

Typically a mature Sumatran rhino stands about 130 cm (51 in) high at the shoulder, a body length of 240–315 cm (94–124 in) and weighs around 700 kg (1,500 lb), though the largest individuals have been known to weigh as much as 1,000 kilograms. Like the African species, it has two horns; the largest is the front (25–79 cm) and the smaller being the second, which is usually less than 10 cm long. The males have much larger horns than the females. Hair can range from dense (the most dense hair in young calves) to scarce. The color of these rhinos is reddish brown. The body is short and has stubby legs. They also have a prehensile lip.

Evolution

Rhinocerotoids diverged from other perissodactyls by the early Eocene. Fossils of Hyrachyus eximus found in North America date to this period. This small hornless ancestor resembled a tapir or small horse more than a rhino. Three families, sometimes grouped together as the superfamily Rhinocerotoidea, evolved in the late Eocene: Hyracodontidae, Amynodontidae and Rhinocerotidae.

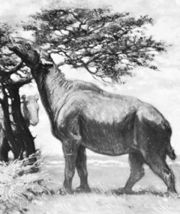

Hyracodontidae, also known as "running rhinos," showed adaptations for speed, and would have looked more like horses than modern rhinos. The smallest hyracodontids were dog-sized; the largest was Indricotherium, believed to be one of the largest land mammals that ever existed. The hornless Indricotherium was almost seven metres high, ten metres long, and weighed as much as 15 tons. Like a giraffe, it ate leaves from trees. The Hyracodontids spread across Eurasia from the mid-Eocene to early Miocene.

The family Amynodontidae, also known as "aquatic rhinos," dispersed across North America and Eurasia, from the late Eocene to early Oligocene. The amynodontids were hippopotamus-like in their ecology and appearance, inhabiting rivers and lakes, and sharing many of the same adaptations to aquatic life as hippos.

The family of all the modern rhinoceros, the Rhinocerotidae, first appeared in the Late Eocene in Eurasia. The earliest members of Rhinocerotidae were small and numerous; at least 26 genera lived in Eurasia and North America until a wave of extinctions in the middle Oligocene wiped out most of the smaller species. Several independent lineages survived, however. Menoceras, a pig-sized rhinoceros which had two horns side-by-side or the Teleoceras of North America which had short legs and a barrel chest and lived until about 5 million years ago. The last rhinos in America became extinct during the Pliocene.

Modern rhinos are believed to have dispersed from Asia beginning in the Miocene. Two species survived the most recent period of glaciation and inhabited Europe as recently as 10,000 years ago. The woolly rhinoceros appeared in China around 1 million years ago and first arrived in Europe around 600,000 years ago and again 200,000 years ago, where alongside the woolly mammoth, they became numerous but eventually were hunted to extinction by early humans. Another species of enormous rhino, Elasmotherium, survived through the middle Pleistocene. Also known as the giant rhinoceros, Elasmotherium was two meters tall, five meters long and weighed around five tons, with a single enormous horn, hypsodont teeth and long legs for running.

Of the extant rhinoceros species, the Sumatran Rhino is the most archaic, first emerging more than 15 million years ago. The Sumatran Rhino was closely related to the woolly rhinoceros, but not to the other modern species. The Indian Rhino and Javan Rhino are closely related and from a more recent lineage of Asian rhino. The ancestors of early Indian and Javan rhino emerged 2-4 million years ago.[16]

The origin of the two living African rhinos can be traced back to the late Miocene (6 mya) species Ceratotherium neumayri. The lineages containing the living species diverged by the early Pliocene (1.5 mya), when Diceros praecox, the likely ancestor of the Black Rhinoceros, appears in the fossil record.[17] The black and white rhinoceros remain so closely related that they can still mate and successfully produce offspring.[6]

- Family Rhinocerotidae[18]

- Subfamily Rhinocerotinae

- Tribe Aceratheriini

- †Aceratherium lived from 33.9—3.4 Ma

- †Acerorhinus 13.6—7.0 Ma

- †Alicornops 13.7—5.33 Ma

- †Aphelops 20.430—5.330 Ma

- †Chilotheridium 23.03—11.610 Ma

- †Chilotherium 13.7—3.4 Ma

- †Dromoceratherium 15.97—7.25 Ma

- †Floridaceras 20.43—16.3 Ma

- †Hoploaceratherium 16.9—16.0 Ma

- †Mesaceratherium

- †Peraceras 20.6—10.3 Ma

- †Plesiaceratherium 20.0—11.6 Ma

- †Proaceratherium 16.9—16.0 Ma

- †Sinorhinus

- †Subchilotherium

- Tribe Teleoceratini

- †Aprotodon 28.4—5.330 Ma

- †Brachydiceratherium

- †Brachypodella

- †Brachypotherium 20.0—5.33 Ma

- †Diaceratherium 28.4—16.0 Ma

- †Prosantorhinus 16.9—7.25 Ma

- †Shennongtherium

- †Teleoceras 16.9—4.9 Ma

- Tribe Rhinocerotini 40.4—11.1 Ma

- †Gaindatherium 11.61—11.1 Ma

- Rhinoceros - Indian & Javan Rhinoceros

- Tribe Dicerorhinini 5.330—0.011 Ma

- †Coelodonta - Woolly Rhinoceros

- Dicerorhinus - Sumatran Rhinoceros 23.030—0.110 Ma

- †Dihoplus 11.610—1.810 Ma

- †Lartetotherium 15.97—8.7 Ma

- †Stephanorhinus 9.7—0.126 Ma - Merck´s Rhinoceros & Narrow-nosed Rhinoceros

- Tribe Dicerotini 23.03—Present

- Ceratotherium - White Rhinoceros 7.250—Present

- Diceros - Black Rhinoceros 23.03—Present

- †Paradiceros 15.97—11.61 Ma

- Tribe Aceratheriini

- Subfamily Elasmotheriinae

- †Gulfoceras 23.030—20.430 Ma

- Tribe Diceratheriini

- †Diceratherium 33.9—11.610 Ma

- †Subhyracodon 38.0—26.3 Ma

- Tribe Elasmotheriini 20.0—0.126 Ma

- †Bugtirhinus 20.0—16.9 Ma

- †Caementodon

- †Elasmotherium - Giant Rhinoceros 3.6—0.126 Ma

- †Hispanotherium synonymized with Huaqingtherium 16.0—7.250 Ma

- †Iranotherium

- †Kenyatherium

- †Meninatherium

- †Menoceras 23.03—16.3 Ma

- †Ougandatherium 20.0—16.9 Ma

- †Parelasmotherium

- †Procoelodonta

- †Sinotherium 9.0—5.3 Ma

- Subfamily Rhinocerotinae

Predators

In the wild, adult rhinoceros have few natural predators other than humans. Young rhinos can fall prey to predators such as big cats, crocodiles, wild dogs, and hyena. It has also been reported that a large Nile crocodile (Crocodylus niloticus) was seen taking a black rhino while it was drinking from a river; whether other species of rhino may fall prey to these large reptiles is unknown. Although rhinos are of large size and have a reputation of being tough, they are actually very easily poached. Because it visits water holes daily, the rhinoceros is easily killed while taking a drink. As of December 2009 poaching has been on a "global" increase whilst efforts to protect the rhinoceros are being considered increasingly ineffective. The worst estimate, that only 3% of poachers are successfully countered, is reported of Zimbabwe. Rhino horn is considered to be particularly effective on fevers and even "life saving" by traditional Chinese medicine practitioners, which in turn provides a sales market. Nepal is apparently alone in avoiding the crisis while poacher-hunters grow ever more sophisticated.[19] South African officials are calling for urgent action against rhinoceros poaching after poachers killed the last female rhinoceros in Krugersdorp Park near Johannesburg.[20]

Horns

The most obvious distinguishing characteristic of the rhinos is a large horn above the nose. Rhinoceros horns, unlike those of other horned mammals, consist of keratin only and lack a bony core, such as bovine horns. Rhinoceros horns are used in traditional Asian medicine, and for dagger handles in Yemen and Oman. Esmond Bradley Martin has reported on the trade for dagger handles in Yemen. [2]

One repeated misconception is that rhinoceros horn in powdered form is used as an aphrodisiac in Traditional Chinese Medicine as Cornu Rhinoceri Asiatici (犀角). It is, in fact, prescribed for fevers and convulsions.[21] Discussions with TCM practitioners to reduce its use have met with mixed results since some TCM doctors mistakenly see rhinoceros horn as a life-saving medicine of better quality than substitutes.[22] China has signed the CITES treaty however. To prevent poaching, in certain areas, rhinos have been tranquilized and their horns removed. Many rhino range States have stockpiles of rhino horn.[23]

Historical representations

Albrecht Dürer created a famous woodcut of a rhinoceros in 1515, based on a written description and brief sketch by an unknown artist of an Indian rhinoceros that had arrived in Lisbon earlier that year. Dürer never saw the animal itself, and as a result, Dürer's Rhinoceros is a somewhat inaccurate depiction.

There are legends about rhinoceros stamping out fire in Malaysia, India, and Burma. The mythical rhinoceros has a special name in Malay, badak api, where badak means rhinoceros and api means fire. The animal would come when a fire is lit in the forest and stamp it out.[24] There are no recent confirmations of this phenomenon. However, this legend has been reinforced by the film The Gods Must Be Crazy, where an African rhinoceros is shown to be putting out two campfires.[25]

Footnotes

- ↑ Owen-Smith, Norman (1984). Macdonald, D.. ed. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. pp. 490–495. ISBN 0-87196-871-1.

- ↑ What is a rhinoceros horn made of?

- ↑ San Diego Zoo

- ↑ Rookmaaker, Kees (2003). "Why the name of the white rhinoceros is not appropriate". Pachyderm 34: 88–93.

- ↑ Rabinowitz, Alan (June 1995) "Helping a Species Go Extinct: The<33 six. Sumatran Rhino in Borneo" Conservation Biology 9(3): pp. 482-488

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Robinson, Terry J.; V. Trifonov, I. Espie, E.H. Harley (01 2005). "Interspecific hybridization in rhinoceroses: Confirmation of a Black × White rhinoceros hybrid by karyotype, fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and microsatellite analysis". Conservation Genetics 6 (1): 141–145. doi:10.1007/s10592-004-7750-9. http://www.springerlink.com/openurl.asp?genre=article&doi=10.1007/s10592-004-7750-9.

- ↑ Times Online | News | Environment | Poachers kill last four wild northern white rhinos

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "African Rhinoceros". Safari Now. http://196.36.153.129/cms/african-rhino/irie.aspx. Retrieved 2008-03-19.

- ↑ "West African black rhino 'is extinct'". The Times. July 7, 2006. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,3-2260631,00.html. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ↑ Dollinger, Peter and Silvia Geser. "Black Rhinoceros". World Association of Zoos and Aquariums. http://www.waza.org/virtualzoo/factsheet.php?id=118-003-003-001&view=Rhinos&main=virtualzoo. Retrieved 2007-10-09.

- ↑ Bhaumik, Subir (17 April 2007). "Assam rhino poaching 'spirals'". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/south_asia/6564337.stm. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

- ↑ Derr, Mark (July 11, 2006). "Racing to Know the Rarest of Rhinos, Before It’s Too Late". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2006/07/11/science/11rhin.html?_r=1. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ↑ Species Endangered: Javan Rhinoceros

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Rhino Guide: Javan Rhinoceros

- ↑ Lacombat, Frédéric (2005). "The evolution of the rhinoceros". In Fulconis, R.. Save the rhinos: EAZA Rhino Campaign 2005/6. London: European Association of Zoos and Aquaria. pp. 46–49.

- ↑ Geraads, Denis (2005). "Pliocene Rhinocerotidae (Mammalia) from Hadar and Dikika (Lower Awash, Ethiopia), and a revision of the origin of modern African rhinos". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (2): 451–460. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2005)025[0451:PRMFHA]2.0.CO;2. http://www.vertpaleo.org/publications/jvp/25-451-461.cfm.

- ↑ Haraamo, Mikko (2005-11-15). "Mikko's Phylogeny Archive entry on "Rhinoceratidae"". http://www.fmnh.helsinki.fi/users/haaramo/metazoa/deuterostoma/chordata/synapsida/eutheria/Perissodactyla/Rhinocerotidae/Rhinocerotidae.htm. Retrieved 2008-01-07.

- ↑ 'Global surge' in rhino poaching BBC

- ↑ "Poachers kill last female rhino in South African park for prized horn". National Ledger. July 20, 2010. http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2010/jul/18/poachers-kill-last-female-rhino. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- ↑ Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, Third Edition, by Dan Bensky, Steven Clavey, Erich Stoger, and Andrew Gamble. September 2004

- ↑ Parry-Jones, Rob and Amanda Vincent (January 3, 1998). "Can we tame wild medicine? To save a rare species, Western conservationists may have to make their peace with traditional Chinese medicine.". New Scientist 157 (2115). http://seahorse.fisheries.ubc.ca/pdfs/parryjones_and_vincent1998_newscientist.html.

- ↑ Milledge, Simon. Rhino Horn StockpilePDF (1.34 MB), TRAFFIC, 2005. Retrieved 2008-01-09.

- ↑ Rhinoceros Frequently Asked Questions

- ↑ The Gods Must Be Crazy, James Uys, C.A.T. Films, 1980.

References

- Cerdeño, Esperanza (1995). "Cladistic Analysis of the Family Rhinocerotidae (Perissodactyla)". Novitates (American Museum of Natural History) (3143). ISSN 0003-0082. http://digitallibrary.amnh.org/dspace/bitstream/2246/3566/1/N3143.pdf

- Chapman, January 1999. The Art of Rhinoceros Horn Carving in China. Christies Books, London. ISBN 0-903432-57-9.

- Emslie, R. and Brooks, M. (1999). African Rhino. Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN/SSC African Rhino Specialist Group. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. ISBN 2831705029

- Foose, Thomas J. and van Strien, Nico (1997). Asian Rhinos – Status Survey and Conservation Action Plan. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland, and Cambridge, UK. ISBN 2-8317-0336-0

- Hieronymus, Tobin L.; Lawrence M. Witmer and Ryan C. Ridgely (2006). "Structure of White Rhinoceros (Ceratotherium simum) Horn Investigated by X-ray Computed Tomography and Histology With Implications for Growth and External Form". Journal of Morphology 267 (10): 1172–1176. doi:10.1002/jmor.10465. PMID 16823809. http://www.oucom.ohiou.edu/dbms-witmer/Downloads/2006_Hieronymus-Witmer-Ridgely_rhino_horn.pdf

- Laufer, Berthold. 1914. "History of the Rhinoceros." In: Chinese Clay Figures, Part I: Prolegomena on the History of Defence Armour. Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, pp. 73–173.

- White Rhinoceros, White Rhinoceros Profile, Facts, Information, Photos, Pictures, Sounds, Habitats, Reports, News - National Geographic

- Unattributed. "White Rhino (Ceratotherum simum)" (in en-US). Rhinos. The International Rhino Foundation. http://www.rhinos-irf.org/white/. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

External links

- Rhino Species & Rhino Images page on the Rhino Resource Center

- Rhinoceros entry on World Wide Fund for Nature website.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||