Rectangle

| Rectangle | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Family | Orthotope |

| Type | Quadrilateral |

| Edges and vertices | 4 |

| Schläfli symbol | {}x{} |

| Symmetry group | D2 (*2) |

| Coxeter-Dynkin diagram | |

| Dual polygon | Rhombus |

| Properties | isogonal, convex, cyclic |

In Euclidean plane geometry, a rectangle is any quadrilateral with four right angles. The term "oblong" is occasionally used to refer to a non-square rectangle.[1][2] A rectangle with vertices ABCD would be denoted as ABCD.

A so-called crossed rectangle is a crossed (self-intersecting) quadrilateral which consists of two opposite sides of a rectangle along with the two diagonals.[3] Its angles are not right angles. Other geometries, such as spherical, elliptic, and hyperbolic, have so-called rectangles with opposite sides equal in length and equal angles that are not right angles.

Rectangles are involved in many tiling problems, such as tiling the plane by rectangles or tiling a rectangle by polygons.

Contents |

Classification

Traditional hierarchy

A rectangle is a special case of a parallelogram, whose opposite sides are equal in length and parallel to each other.

A parallelogram, and hence also a rectangle, is a special case of a trapezium (known as a trapezoid in North America), which has at least one pair of parallel opposite sides.

A trapezium, and hence also a rectangle, is convex. Any line drawn through it (and not tangent to an edge or corner) meets its boundary exactly twice.

A convex quadrilateral, and hence also a rectangle, is

- Star-shaped: The whole interior is visible from a single point, without crossing any edge.

- Simple: The boundary does not cross itself.

Alternative hierarchy

De Villiers defines a rectangle more generally as any quadrilateral with axes of symmetry through each pair of opposite sides.[4] This definition includes both right-angled rectangles and crossed rectangles. Each has an axis of symmetry parallel to and equidistant from a pair of opposite sides, and another which is the perpendicular bisector of those sides, but, in the case of the crossed rectangle, the first axis is not an axis of symmetry for either side that it bisects.

Quadrilaterals with two axes of symmetry, each through a pair of opposite sides, belong to the larger class of quadrilaterals with at least one axis of symmetry through a pair of opposite sides. These quadrilaterals comprise isosceles trapezia and crossed isosceles trapezia (crossed quadrilaterals with the same vertex arrangement as isosceles trapezia).

Properties

Symmetry

A rectangle is cyclic: all corners lie on a single circle.

It is equiangular: all its corner angles are equal (each of 90 degrees).

It is isogonal or vertex-transitive: all corners lie within the same symmetry orbit.

It has two lines of reflectional symmetry and rotational symmetry of order 2 (through 180°).

Rectangle-rhombus duality

The dual polygon of a rectangle is a rhombus, as shown in the table below.

| Rectangle | Rhombus |

|---|---|

| All angles are congruent. | All sides are congruent. |

| Its centre is equidistant from its vertices, hence it has a circumcircle. | Its centre is equidistant from its sides, hence it has an incircle. |

| Its axes of symmetry bisect opposite sides. | Its axes of symmetry bisect opposite angles. |

Miscellaneous

The two diagonals are equal in length and bisect each other. Every quadrilateral with both these properties is a rectangle.

A rectangle is rectilinear: its sides meet at right angles.

A non-square rectangle has 5 degrees of freedom, comprising 2 for position, 1 for rotational orientation, 1 for overall size, and 1 for shape.

Two rectangles, neither of which will fit inside the other, are said to be incomparable.

Formulas

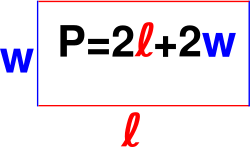

If a rectangle has length  and width

and width

Theorems

The isoperimetric theorem for rectangles states that among all rectangles of a given perimeter, the square has the largest area.

The midpoints of the sides of any quadrilateral with perpendicular diagonals form a rectangle.

The Japanese theorem for cyclic quadrilaterals[5] states that the incentres of the four triangles determined by the vertices of a cyclic quadrilateral taken three at a time form a rectangle.

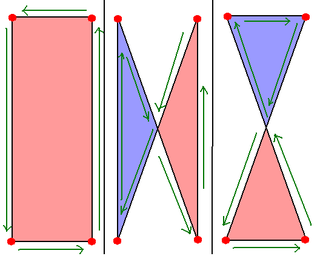

Crossed rectangles

A crossed (self-intersecting) quadrilateral consists of two opposite sides of a non-self-intersecting quadrilateral along with the two diagonals. Similarly, a crossed rectangle is a crossed quadrilateral which consists of two opposite sides of a rectangle along with the two diagonals. It has the same vertex arrangement as the rectangle. It appears as two identical triangles with a common vertex, but the geometric intersection is not considered a vertex.

A crossed quadrilateral is sometimes likened to a bow tie or butterfly. A three-dimensional rectangular wire frame that is twisted can take the shape of a bow tie. A crossed rectangle is sometimes called an "angular eight".

The interior of a crossed rectangle can have a polygon density of +/-1 in each triangle, dependent upon the winding orientation as clockwise or counterclockwise.

A crossed rectangle is not equiangular. The sum of its interior angles (two acute and two reflex), as with any crossed quadrilateral, is 720°. [6]

A rectangle and a crossed rectangle are quadrilaterals with the following properties in common:

- Opposite sides are equal in length.

- The two diagonals are equal in length.

- It has two lines of reflectional symmetry and rotational symmetry of order 2 (through 180°).

Other rectangles

In solid geometry, a figure is non-planar if it is not contained in a (flat) plane. A skew rectangle is a non-planar quadrilateral with opposite sides equal in length and four equal acute angles.[7] A saddle rectangle is a skew rectangle with vertices that alternate an equal distance above and below a plane passing through its center, named for its minimal surface interior seen with saddle point at its center.[8] The convex hull of this skew rectangle is a special tetrahedron called a rhombic disphenoid. (The term "skew rectangle" is also used in 2D graphics to refer to a distortion of a rectangle using a "skew" tool. The result can be a parallelogram or a trapezoid/trapezium.)

In spherical geometry, a spherical rectangle is a figure whose four edges are great circle arcs which meet at equal angles greater than 90 degrees. Opposite arcs are equal in length. The surface of a sphere in Euclidean solid geometry is a non-Euclidean surface in the sense of elliptic geometry. Spherical geometry is the simplest form of elliptic geometry.

In elliptic geometry, an elliptic rectangle is a figure in the elliptic plane whose four edges are elliptic arcs which meet at equal angles greater than 90 degrees. Opposite arcs are equal in length.

In hyperbolic geometry, a hyperbolic rectangle is a figure in the hyperbolic plane whose four edges are hyperbolic arcs which meet at equal angles less than 90 degrees. Opposite arcs are equal in length.

Tessellations

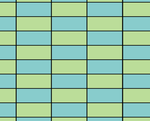

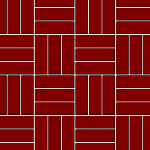

The rectangle is used in many periodic tessellation patterns, in brickwork, for example, these isogonal tilings:

Stacked bond |

Running bond |

Basket weave |

Basket weave |

Herringbone pattern |

Squared, perfect, and other tiled rectangles

A rectangle tiled by squares, rectangles, or triangles is said to be a "squared", "rectangled", or "triangled" (or "triangulated") rectangle respectively. The tiled rectangle is perfect[9][10] if the tiles are similar and finite in number and no two tiles are the same size. If two such tiles are the same size, the tiling is imperfect. In a perfect (or imperfect) triangled rectangle the triangles must be right triangles.

A rectangle has commensurable sides if and only if it is tileable by a finite number of unequal squares.[9][11] The same is true if the tiles are unequal isosceles right triangles.

The tilings of rectangles by other tiles which have attracted the most attention are those by congruent non-rectangular polyominoes, allowing all rotations and reflections. There are also tilings by congruent polyaboloes.

See also

- Cuboid

- Hyperrectangle

- Golden rectangle

References

- ↑ http://www.mathsisfun.com/definitions/oblong.html

- ↑ http://www.icoachmath.com/SiteMap/Oblong.html

- ↑ Coxeter, Harold Scott MacDonald; Longuet-Higgins, M. S.; Miller, J. C. P. (1954). "Uniform polyhedra". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series A. Mathematical and Physical Sciences (The Royal Society) 246 (916): 401–450. doi:10.1098/rsta.1954.0003. MR0062446. ISSN 0080-4614. http://www.jstor.org/stable/91532.

- ↑ An Extended Classification of Quadrilaterals (An excerpt from De Villiers, M. 1996. Some Adventures in Euclidean Geometry. University of Durban-Westville.)

- ↑ Cyclic Quadrilateral Incentre-Rectangle with interactive animation illustrating a rectangle that becomes a 'crossed rectangle', making a good case for regarding a 'crossed rectangle' as a type of rectangle.

- ↑ Stars: A Second Look

- ↑ http://mathworld.wolfram.com/SkewQuadrilateral.html

- ↑ Williams, Robert (1979). The Geometrical Foundation of Natural Structure: A Source Book of Design. Dover Publications, Inc. ISBN 0-486-23729-X. "Skew Polygons (Saddle Polygons)." §2.2

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 R.L. Brooks, C.A.B. Smith, A.H. Stone and W.T. Tutte (1940). "The dissection of rectangles into squares". Duke Math. J. 7 (1): 312–340. doi:10.1215/S0012-7094-40-00718-9. http://projecteuclid.org/euclid.dmj/1077492259.

- ↑ J.D. Skinner II, C.A.B. Smith and W.T. Tutte (November 2000). "On the Dissection of Rectangles into Right-Angled Isosceles Triangles". J. Combinatorial Theory Series B 80 (2): 277–319. doi:10.1006/jctb.2000.1987.

- ↑ R. Sprague (1940). "Ũber die Zerlegung von Rechtecken in lauter verschiedene Quadrate". J. fũr die reine und angewandte Mathematik 182: 60–64.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Rectangle" from MathWorld.

- Definition and properties of a rectangle with interactive animation.

- Area of a rectangle with interactive animation.

,

, ,

, ,

, , the rectangle is a

, the rectangle is a