Rabbi

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Jews and Judaism |

|---|

|

| Who is a Jew? · Etymology · Culture |

|

God in Judaism (Names)

Principles of faith · Mitzvot (613) Halakha · Shabbat · Holidays Prayer · Tzedakah Brit · Bar / Bat Mitzvah Marriage · Bereavement Philosophy · Ethics · Kabbalah Customs · Synagogue · Rabbi |

|

Ashkenazi · Sephardi · Mizrahi

Romaniote · Italki · Yemenite African · Beta Israel · Bukharan · Georgian • German · Mountain · Chinese Indian · Khazars · Karaim • Krymchaks • Samaritans • Crypto-Jews |

|

Population

Jews by country · Rabbis

Population comparisons Lists of Jews |

|

Denominations

Alternative · Conservative

Humanistic · Karaite · Liberal · Orthodox · Reconstructionist Reform · Renewal · Traditional |

|

Timeline · Leaders

Ancient · Kingdom of Judah Temple Babylonian exile Yehud Medinata Hasmoneans · Sanhedrin Schisms · Pharisees Jewish-Roman wars Christianity and Judaism Islam and Judaism Diaspora · Middle Ages Sabbateans · Hasidism · Haskalah Emancipation · Holocaust · Aliyah Israel (history) Arab conflict · Land of Israel Baal teshuva · Persecution Antisemitism (history) |

|

Politics

|

In Judaism, a rabbi (pronounced /ˈræbaɪ/, Hebrew for "teacher") is a religious teacher.

The basic form of the rabbi developed in the Pharisaic and Talmudic era, when learned teachers assembled to codify Judaism's written and oral laws. In more recent centuries, the duties of the rabbi became increasingly influenced by the duties of the Protestant Christian Minister, hence the title "pulpit rabbis", and in 19th century Germany and the United States rabbinic activities including sermons, pastoral counseling, and representing the community to the outside, all increased in importance.

Within the various Jewish denominations there are different requirements for rabbinic ordination, and differences in opinion regarding who is to be recognized as a rabbi. All types of Judaism except for Orthodox Judaism ordain women as rabbis and cantors [3] [4].

Contents |

The word 'rabbi'

Etymology and history

The word rabbi derives from the Hebrew root word רַב, rav, which in biblical Hebrew means ‘great’ in many senses, including "revered". The word comes from the Semitic root R-B-B, and is cognate to Arabic ربّ rabb, meaning "lord" (generally used when talking about God, but also about temporal lords). As a sign of great respect, some great rabbis are simply called "The Rav".

Rabbi is not an occupation found in the Torah (i.e. the Pentateuch) as such, and ancient generations did not employ related titles such as Rabban, Ribbi, or Rab to describe either the Babylonian sages or the sages in Israel.[1] Even the very eminent Biblical prophets are referred to as "Haggai the prophet" e.g. The titles "Rabban" and "Rabbi" are first mentioned in Hebrew scriptures in the Mishnah (c. 200 CE). The term was first used for Rabban Gamaliel the elder, Rabban Simeon his son, and Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai, all of whom were patriarchs or presidents of the Sanhedrin.[2] A Greek transliteration of the word is also found in the books of Matthew, Mark and John in the New Testament, where it is used in reference to Jesus.[3]

Pronunciation

Sephardic and Yemenite Jews pronounce this word רִבִּי ribbī; the modern Israeli pronunciation רַבִּי rabbī is derived from an 18th century innovation in Ashkenazic prayer books, although this vocalization is also found in some ancient sources. Other variants are rəvī and, in Yiddish, rebbə. The word could be compared to the Syriac word rabi ܪܒܝ.

In ancient Hebrew, rabbi was a proper term of address while speaking to a superior, in the second person, similar to a vocative case. While speaking about a superior, in the third person one could say Ha-Rav ("the Master") or Rabbo ("his Master"). Later, the term evolved into a formal title for members of the Patriarchate. Thus, the title gained an irregular plural form: רַבָּנִים Rabbanim ("rabbis"), and not רַבָּי Rabbai ("my Masters").

Honor

There is a mitzvah to stand up for a Rabbi or Torah Scholar when they enter your presence. [4] However, if one is more learned than the Rabbi there is no need to stand. One must also stand for the wife of a Rabbi or Torah Scholar and address them with much respect. In many places today and throughout history, Rabbis and Torah Scholars had the power to place individuals who insulted them in excommunication. However, they were praised for never doing so when it came to personal honor. [5] Kohanim, like everyone else, are required to honor Rabbis and Torah Scholars.[6]

The definition of a Torah Scholar is complex and subjective.

Historical overview

The governments of the Kingdoms of Israel and Judah were based on a system of Jewish kings, prophets, the legal authority of the court of the Sanhedrin and the ritual authority of priesthood. Members of the Sanhedrin had to receive their semicha ("ordination") derived in an uninterrupted line of transmission from Moses, yet rather than being referred to as "rabbis" they were more frequently called judges (dayanim) akin to the Shoftim or "Judges" as in the Book of Judges.

All of the above personalities would have been expected to be steeped in the wisdom of the Torah and the commandments, which would have made them "rabbis" in the modern sense of the word. This is illustrated by an two-thousand-year-old teaching in the Mishnah, Ethics of the Fathers (Pirkei Avot), which observed about King David,

- "He who learns from his fellowman a single chapter, a single halakha, a single verse, a single Torah statement, or even a single letter, must treat him with honor. For so we find with David King of Israel, who learned nothing from Ahitophel except two things, yet called him his teacher [Hebrew text: "rabbo"], his guide, his intimate, as it is said: 'You are a man of my measure, my guide, my intimate' (Psalms 55:14). One can derive from this the following: If David King of Israel who learned nothing from Ahitophel except for two things, called him his teacher, his guide, his intimate, one who learns from his fellowman a single chapter, a single halakha, a single verse, a single statement, or even a single letter, how much more must he treat him with honor. And honor is due only for Torah, as it is said: 'The wise shall inherit honor' (Proverbs 3:35), 'and the perfect shall inherit good' (Proverbs 28:10). And only Torah is truly good, as it is said: 'I have given you a good teaching, do not forsake My Torah' (Psalms 128:2)." (Ethics of the Fathers 6:3)

With the destruction of the two Temples in Jerusalem, the end of the Jewish monarchy, and the decline of the dual instititutions of prophets and the priesthood, the focus of scholarly and spiritual leadership within the Jewish people shifted to the sages of the Men of the Great Assembly (Anshe Knesset HaGedolah). This assembly was composed of the earliest group of "rabbis" in the more modern sense of the word, in large part because they began the formulation and explication of what became known as Judaism's "Oral Law (Torah SheBe'al Peh). This was eventually encoded and codified within the Mishnah and Talmud and subsequent rabbinical scholarship, leading to what is known as Rabbinic Judaism.

Sages

The title "Rabbi" was borne by the sages of ancient Israel, who were ordained by the Sanhedrin in accordance with the custom handed down by the elders. They were titled Ribbi and received authority to judge penal cases. Rab was the title of the Babylonian sages who taught in the Babylonian academies.

After the suppression of the Patriarchate and Sanhedrin by Theodosius II in 425, there was no more formal ordination in the strict sense. A recognised scholar could be called Rab or Hacham, like the Babylonian sages. The transmission of learning from master to disciple remained of tremendous importance, but there was no formal rabbinic qualification as such.

Middle Ages

Maimonides rules that every congregation is obliged to appoint a preacher and scholar to admonish the community and teach Torah, and the social institution he describes is the germ of the modern congregational rabbinate. In the fifteenth century in Central Europe, the custom grew up of licensing scholars with a diploma entitling them to be called Mori (my teacher). At the time this was objected to as hukkat ha-goy (imitating the ways of the Gentiles), as it was felt to resemble the conferring of doctorates in Christian universities. However the system spread, and it is this diploma that is referred to as semicha (ordination) at the present day.

18th-19th century

In 19th century Germany and the United States, the duties of the rabbi became increasingly influenced by the duties of the Protestant Christian Minister, hence the title "pulpit rabbis". Sermons, pastoral counseling, representing the community to the outside, all increased in importance. Non-Orthodox rabbis, on a day-to-day business basis, now spend more time on these traditionally non-rabbinic functions than they do teaching, or answering questions on Jewish law and philosophy. Within the Modern Orthodox community, rabbis still mainly deal with teaching and questions of Jewish law, but are increasingly dealing with these same pastoral functions. Orthodox Judaism's National Council of Young Israel and Modern Orthodox Judaism's Rabbinical Council of America have set up supplemental pastoral training programs for their rabbis.

Traditionally, rabbis have never been an intermediary between God and humans. This idea was traditionally considered outside the bounds of Jewish theology. Unlike spiritual leaders in many other faiths, they are not considered to be imbued with special powers or abilities.

In an ironic twist, the secular system in most states requires that a Jewish wedding be performed by an ordained rabbi in order to be legally recognized, even though there is no such requirement in Jewish law. In other words, the secular system treats rabbis as the Jewish equivalent to Catholic Priests or Protestant Ministers, although they are not religious equivalents.

Authority

Acceptance of rabbinic credentials involves both issues of practicality and principle.

As a practical matter, communities and individuals typically tend to follow the authority of the rabbi they have chosen as their leader (called by some as the mara d'atra) on issues of Jewish law. They may recognize that other rabbis have the same authority elsewhere, but for decisions and opinions important to them they will work through their own rabbi.

The same pattern is true within broader communities, ranging from Hasidic communities to rabbinical or congregational organizations: there will be a formal or de facto structure of rabbinic authority that is responsible for the members of the community.

Ordination

Traditionally, a person obtains semicha ("rabbinic ordination") after the completion of an arduous learning program in the codes of Jewish law and responsa.

The most general form of semicha is Yore yore ("he shall teach"). Most Rabbis hold this qualification; they are sometimes called a moreh hora'ah ("a teacher of rulings"). A more advanced form of semicha is Yadin yadin ("he shall judge"). This enables the recipient to adjudicate cases of monetary law, amongst other responsibilities. Although the recipient can now be formally addressed as a dayan ("judge"), the vast majority retain the title rabbi. Only a small percentage of rabbis earn this ordination. Although not strictly necessary, many Orthodox rabbis hold that a beth din (court of Jewish law) should be made up of dayanim.

Orthodox Judaism

An Orthodox semicha requires the successful completion of a rigorous program encompassing Jewish law and responsa in keeping with longstanding tradition. Orthodox rabbinical students work to gain knowledge in Talmud, Rishonim and Acharonim (early and late medieval commentators) and Jewish law. They study sections of the Shulchan Aruch (codified Jewish law) and its main commentaries that pertain to daily-life questions (such as the laws of keeping kosher, Shabbat, and the laws of sex as it relates to family purity). Orthodox rabbis typically study at yeshivas, which are dedicated religious schools. Modern Orthodox rabbinical students, such as those at Yeshiva University, study some elements of modern theology or philosophy, as well as the classical rabbinic works on such subjects.

The entrance requirements for an Orthodox yeshiva include a strong background within Jewish law, liturgy, Talmudic study, and attendant languages (e.g., Hebrew, Aramaic and in some cases Yiddish). Since rabbinical studies typically flow from other yeshiva studies, those who seek a semicha are typically not required to have completed a university education. There are some exceptions to this rule, including Yeshiva University , which requires all rabbinical students to complete an undergraduate degree before entering the program and a Masters or equivalent before ordination. Yeshivat Chovevei Torah Rabbinical School also requires an undergraduate degree before entering the program.

Haredi Judaism

While some Haredi (including Hasidic) yeshivas (also known as "Talmudical/Rabbinical schools or academies") do grant official semicha ("ordination") to many students wishing to become rabbis, most of the students within the yeshivas engage in learning Torah or Talmud without the goal of becoming rabbis or holding any official positions.

The curriculum for obtaining semicha ("ordination") as rabbis for Haredi and Hasidic scholars is the same as described above for all Orthodox students wishing to obtain the official title of "Rabbi" and to be recognized as such.

Women do not, and cannot, become rabbis in Orthodox Judaism. Only men can do so, and only after a long process of study in, and recognition by, their own yeshivas.

Within the Hasidic world, the positions of spiritual leadership are dynastically transmitted within established families, usually from fathers to sons, while a small number of students obtain official ordination to become dayanim ("judges") on religious courts, poskim ("decisors" of Jewish law), as well as teachers in the Hasidic schools. The same is true for the non-Hasidic Litvish yeshivas that are controlled by dynastically transmitted rosh yeshivas and the majority of students will not become rabbis, even after many years of post-graduate kollel study.

Some yeshivas, such as Yeshiva Chofetz Chaim (in New York) and Yeshiva Ner Yisrael (in Baltimore, Maryland), may encourage their students to obtain semicha and mostly serve as rabbis who teach in other yeshivas or Hebrew day schools. Other yeshivas, such as Yeshiva Chaim Berlin (Brooklyn, New York) or the Mirrer Yeshiva (in Brooklyn and Jerusalem), do not have an official "semicha/rabbinical program" to train rabbis, but provide semicha on an "as needs" basis if and when one of their senior students is offered a rabbinical position but only with the approval of their rosh yeshivas.

Consequently, within the world of Haredi Judaism, the English word and title of "Rabbi" for anyone is often scorned and derided, because in their view the once-lofty title of "Rabbi" has been debased in modern times. This is one reason that Haredim will often prefer using Hebrew names for rabbinic titles based on older traditions, such as: Rav (denoting "[great] rabbi"), HaRav ("the [great] rabbi"), Moreinu HaRav ("our teacher the [great] rabbi"), Moreinu ("our teacher"), Moreinu VeRabeinu HaRav ("our teacher and our rabbi/master the [great] rabbi"), Moreinu VeRabeinu ("our teacher and our rabbi/master"), Rosh yeshiva ("[the] head [of the] yeshiva"), Rosh HaYeshiva ("head [of] the yeshiva"), "Mashgiach" (for Mashgiach ruchani) ("spiritual supervsor/guide"), Mora DeAsra ("teacher/decisor" [of] the/this place"), HaGaon ("the genius"), Rebbe ("[our/my] rabbi"), HaTzadik ("the righteous/saintly"), "ADMOR" ("Adoneinu Moreinu VeRabeinu") ("our master, our teacher and our rabbi/master") or often just plain Reb which is a shortened form of rebbe that can be used by, or applied to, any married Jewish male as the situation applies.

Note: A rebbetzin (a Yiddish usage common among Ashkenazim) or a rabbanit (in Hebrew and used among Sephardim) is the official "title" used for, or by, the wife of any Orthodox, Haredi, or Hasidic rabbi. Rebbetzin may also be used as the equivalent of Reb and is sometimes abbreviated as such as well.

Honor

There is a mitzvah to stand up for a Rabbi or Torah Scholar when they enter your presence. [7] However, if one is more leaned than the Rabbi there is no need to stand. One must also stand for the wife of a Rabbi or Torah Scholar and address them with the utmost respect. [8] In many places today and throughout history, Rabbis and Torah Scholars had the power to place individuals who insulted them in excommunication. [9] Kohanim, like everyone else, are required to honor Rabbis and Torah Scholars.

Conservative and Masorti Judaism

Conservative Judaism confers rabbinic ordination after the completion of a rigorous program in the codes of Jewish law and responsa in keeping with Jewish tradition. Additional requirements include the study of: the Hebrew Bible, Mishna and Talmud, the Midrash literature, Jewish ethics and lore, the codes of Jewish law, the Conservative responsa literature, both traditional and modern Jewish works on theology and philosophy.

Conservative Judaism has less stringent study requirements for Talmud and responsa study compared to Orthodoxy but adds following subjects as requirements for rabbinic ordination: pastoral care and psychology, the historical development of Judaism; and academic biblical criticism.

Entrance requirements to a Conservative rabbinical study include a strong background within Jewish law and liturgy, knowledge of Hebrew, familiarity with rabbinic literature, Talmud, etc., and the completion of an undergraduate university degree. Rabbinical students usually earn a secular degree (e.g., Master of Hebrew Letters) upon graduation. Ordination is granted at the Ziegler School of Rabbinic Studies in Los Angeles, the Rabbinical School of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America in New York, the Schechter Institute for Jewish Studies in Jerusalem, the Jewish Theological Seminary – University of Jewish Studies of Budapest and the Seminario Rabinico Latinoamericano in Buenos Aires (Argentina).

All Conservative seminaries train women as rabbis and cantors.

Reform Judaism

The Reform rabbinical seminaries require students to first earn a bachelor's degree before entering the rabbinate as well as have a basic knowledge of Hebrew.[10] Studies are mandated in pastoral care and psychology, the historical development of Judaism; and academic biblical criticism. In addition, practical rabbinic experience, such as working at a small congregation as a student rabbi one weekend or month or interning at a larger synagogue as a student rabbi is required.

All Reform seminaries train women as rabbis and cantors.

The seminary of Reform Judaism in the United States is Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion. It has campuses in Cincinnati, New York City, Los Angeles, and in Jerusalem. In the United Kingdom the Reform and Liberal movements maintain Leo Baeck College for the training of rabbis, and in Germany the progressive Abraham Geiger College trains Europeans for the rabbinate.

Seminaries unaffiliated with main denominations

There are several possibilities for receiving rabbinic ordination in addition to seminaries maintained by the large Jewish denominations. These include seminaries maintained by smaller denominational movements, and nondenominational (also called "transdenominational" or "postdenominational") Jewish seminaries.

- The Union for Traditional Judaism (UTJ), an offshoot of the left-wing of Orthodoxy and the right-wing of Conservative Judaism, has a seminary in New Jersey[11]; the seminary is accepted by all non-Orthodox rabbis as a valid, traditional rabbinical seminary. The vast majority of Orthodox Jews do not recognize ordination from UTJ. However, it bridges Conservative and Orthodox Judaism, and Modern Orthodox synagogues have hired UTJ rabbis. Though the more mainstream body of Modern Orthodox Judaism, such as the Rabbinical Council of America, does not recognize ordination from UTJ. UTJ only ordains men.

- The Jewish Renewal movement has an ordination program, ALEPH, but no central campus. Orthodox Judaism holds that this program does not produce valid rabbis. Women are ordained as cantors and rabbis in the Jewish Renewal movement.

- The Academy for Jewish Religion, in New York City, since 1956, and the unrelated Academy for Jewish Religion-California, in Los Angeles, since 2000, have been rabbinic (and cantorial) seminaries unaffiliated with any denomination or movement. Hebrew College, near Boston, includes a similarly unaffiliated rabbinic school, opened in the Fall of 2003. These seminaries are accepted by all non-Orthodox rabbis as valid rabbinical seminaries, and they all ordain women as well as men. Orthodox Jews do not consider these ordinations valid, because these seminaries do not consider Orthodox halacha to be binding.

- Humanistic Judaism has the International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism, which currently has two centers of activity: one in Jerusalem and the other in Farmington Hills, Michigan. Both places ordain women as well as men.

- Reconstructionist Judaism has the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College, which is located in Pennsylvania and ordains women and men as rabbis and cantors.

Expectations

There is no formal requirement to have semicha in order to be called "rabbi" by one's students; it is not a title that one gives to oneself. Haredi Judaism and Hasidic Judaism hold that being tested and certified as a rabbi might be a requirement for certain employment opportunities, but in and of itself it is not the ultimate goal to which an individual need aspire. Rather, they encourage their students to study the Torah as an end in itself. Students are also instructed in the study of mussar, or an equivalent, which teaches improvement of one's character. Students are expected to have a general knowledge of the Shulchan Aruch (Code of Jewish Law), so that even when they go into business, or other fields, they will continue to utilize the Torah's teachings, and live their lives in accordance therewith.

Interdenominational recognition

Historically and until the present, recognition of a rabbi relates to a community's perception of the rabbi's competence to interpret Jewish law and act as a teacher on central matters within Judaism. More broadly speaking, it is also an issue of being a worthy successor to a sacred legacy.

As a result, there have always been greater or lesser disputes about the legitimacy and authority of rabbis. Historical examples include Samaritans and Karaites.

The divisions between the various religious branches within Judaism may have their most pronounced manifestation on whether rabbis from one movement recognizes the legitimacy and/or authority of rabbis in another.

As a general rule within Orthodoxy and among some in the Conservative movement, rabbis are reluctant to accept the authority of other rabbis whose Halakhic standards are not as strict as their own. In some cases, this leads to an outright rejection of even the legitimacy of other rabbis; in others, the more lenient rabbi may be recognized as a spiritual leader of a particular community but may not be accepted as a credible authority on Jewish law.

- The Orthodox rabbinical establishment rejects the validity of Conservative, Reform and Reconstructionist rabbis on the grounds that their movements' teachings are in violation of traditional Jewish tenets. Some Modern Orthodox rabbis are respectful toward non-Orthodox rabbis and focus on commonalities even as they disagree on interpretation of some areas of Halakha (with Conservative rabbis) or the authority of Halakha (with Reform and Reconstructionist rabbis).

- Conservative rabbis accept the legitimacy of Orthodox rabbis, though they are often critical of Orthodox positions. Although they would rarely look to Reform or Reconstructionist rabbis for Halakhic decisions, they accept the legitimacy of these rabbis' religious leadership.

- Reform and Reconstructionist rabbis, on the premise that all the main movements are legitimate expressions of Judaism, will accept the legitimacy of other rabbis' leadership, though will not accept their views on Jewish law, since Reform and Reconstructionism reject Halakha as binding.

These debates cause great problems for recognition of Jewish marriages, conversions, and other life decisions that are touched by Jewish law. Orthodox rabbis do not recognize conversions by non-Orthodox rabbis. Conservative rabbis recognise all conversions done according to halakha. Finally, the North American Reform and Reconstructionst movemements recognize patrilineality, under certain circumstances, as a valid claim towards Judaism, whereas Conservative and Orthodox maintain the position expressed in the Talmud and Codes that one can be a Jew only through matrilineality (born of a Jewish mother) or through conversion to Judaism.

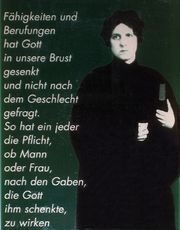

Women

Codes of Jewish law are silent on the issue of women being ordained as rabbis. No prohibition exists, and women who are educated in halacha are entitled to rule on questions of law.[12] However, women in Orthodox Judaism (unlike women in all other types of Judaism) are not eligible to be judges on courts of Jewish law,[13] and may not hold positions of authority over a community.[14] The position of official rabbi of a community, mara de'atra ("master of the place"), has generally been treated in the responsa as such a position.

There were some rare cases of female rabbis in earlier centuries, such as the 17th century Asenath Barzani, who acted as a rabbi among Kurdish Jews [5], and Hannah Rachel Verbermacher, the Maiden of Ludmir, a 19th century female Hasid who fulfilled many of the traditional roles of a Hasidic Rebbe.[15] These cases, however, were isolated and rare.

Today all types of Judaism except for Orthodox Judaism allow and do have female rabbis [6].

The first formally ordained female rabbi was Regina Jonas, ordained in Germany in 1935 [7]. Since 1972, when Sally Priesand became the first female rabbi in Reform Judaism[8], Reform Judaism's Hebrew Union College has ordained 552 women rabbis (as of 2008).[16]

Sandy Eisenberg Sasso became the first female rabbi in Reconstructionist Judaism in 1974 [9], (one of 110 by 2006); and Amy Eilberg became the first female rabbi in Conservative Judaism in 1985 [10](one of 177 by 2006). Lynn Gottlieb became the first female rabbi in Jewish Renewal in 1981 [11], and Tamara Kolton became the very first rabbi of either sex (and therefore, since she was female, the first female rabbi) in Humanistic Judaism in 1999 [12]. In 2009 Alysa Stanton became the world's first African-American female rabbi.[17]

In Europe, Leo Baeck College had ordained 30 female rabbis by 2006 (out of 158 ordinations in total since 1956), starting with Jackie Tabick in 1975.[18]

The consensus of the Orthodox Jewish community has been that women are ineligible to becoming rabbis; the growing calls for Orthodox yeshivas to admit women as rabbinical students have resulted in widespread opposition among the Orthodox rabbinate. Rabbi Norman Lamm, one of the leaders of Modern Orthodoxy and Rosh Yeshiva of Yeshiva University's Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary, opposes giving semicha to women. "It shakes the boundaries of tradition, and I would never allow it." (Helmreich, 1997) Writing in an article in the Jewish Observer, Moshe Y'chiail Friedman states that Orthodox Judaism prohibits women from being given semicha and serving as rabbis. He holds that the trend towards this goal is driven by sociology, and not halakha ("Jewish law"). In his words, the idea is a "quirky fad." [19] No Orthodox rabbinical association (e.g. Agudath Yisrael, Rabbinical Council of America) has allowed women to be ordained using the term rabbi.

However, in the last twenty years Orthodox Judaism has begun to develop clergy-like roles for women as halakhic court advisors and congregational advisors. Some Orthodox Jewish women now serve in Orthodox Jewish congregations in roles that previously were reserved for males, specifically rabbis. The term rabbanit is sometimes used for women in this role.[20]

In Israel, the Shalom Hartman Institute, founded by Orthodox Rabbi David Hartman, is opening a program in 2009 that will grant semicha to women and men of all Jewish denominations, including Orthodox Judaism, although the students are meant to "assume the role of 'rabbi-educators' - not pulpit rabbis- in North American community day schools. [13]" .[21]

Rabbi Aryeh Strikovski (Machanaim Yeshiva and Pardes Institute) worked in the 1990s with Rabbi Avraham Shapira (then a co-Chief rabbi of Israel) to initiate the program for training Orthodox women as halakhic Toanot ("advocates") in rabbinic courts. They have since trained nearly seventy women in Israel. Strikovski states that "The knowledge one requires to become a court advocate is more than a regular ordination, and now to pass certification is much more difficult than to get ordination.". Furthermore, Rav Strikovsky granted ordination to Haviva Ner-David (who is American) in 2006, although she has not been able to find a job as a rabbi.[22]

In Israel a growing number of Orthodox women are being trained as yoatzot halachah.[23]

- …Strikovski and his colleagues aren't willing to confer a title commensurate with experience. Clarifying his position, he laughs, "If a man passed such a test [on Halacha] we would call him a rabbi — but who cares what you call it?" he says. "Rav Soloveitchik, my teacher, always used to say: 'If you know [Jewish law], then you don't need ordination; and if you don't know, then ordination won't make a difference.'" Further, the title of rabbi only had meaning during the time of the Sanhedrin, he argues. "Later titles were modified from generation to generation and community to community, and now the important thing is not the title but that there is a revolution where women can and do study the oral law." + - :(Feldinger, 2005)

Rahel Berkovits, an Orthodox Talmud teacher at Jerusalem's Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies, states that as a result of such changes in Haredi and Modern Orthodox Judaism, "Orthodox women found and oversee prayer communities, argue cases in rabbinic courts, advise on halachic issues, and dominate in social work activities that are all very associated with the role a rabbi performs, even though these women do not have the official title of rabbi."

The use of Toanot is not restricted to any one segment of Orthodoxy; In Israel they have worked with Haredi and Modern Orthodox Jews. Orthodox women may study the laws of family purity at the same level of detail that Orthodox males do at Nishmat, the Jerusalem Center for Advanced Jewish Study for Women. The purpose is for them to be able to act as halakhic advisors for other women, a role that traditionally was limited to male rabbis. This course of study is overseen by Rabbi Yaakov Varhaftig.

Modern Orthodox trends

Furthermore, several efforts are underway within Modern Orthodox communities to include qualified women in activities traditionally limited to rabbis:

- In the United States, Modern Orthodox rabbis Avi Weiss and Saul Berman created an advanced educational institute for women called Torat Miriam. They do not claim that the graduates of this institute are rabbis, but that the long term goal is to have women "work on a professional level in the synagogue," he said. (Helmreich, 1997)

- Rabbi Aryeh Strikovski (Mahanayim Yeshiva and Pardes Institute) worked in the 1990s with Rabbi Avraham Shapira (then a co-Chief rabbi of Israel) to initiate the program for training Orthodox women as halakhic Toanot ("advocates") in rabbinic courts. They have since trained nearly seventy women. Strikovski states that "The knowledge one requires to become a court advocate is more than a regular ordination, and now to pass certification is much more difficult than to get ordination." The use of Toanot is not restricted to any one segment of Orthodoxy; in Israel they have worked with Haredi and Modern Orthodox Jews.

- In Israel a growing number of Orthodox women are being trained as yoatzot halachah, who serve many in the Israeli Haredi community.

- At Nishmat, the Jerusalem Center for Advanced Jewish Study for Women, Orthodox women may study the laws of family purity at the same level of detail that Orthodox males do. The purpose is for them to be able to act as halakhic advisors for other women, a role that traditionally was limited to male rabbis. This course of study is overseen by Rabbi Yaakov Varhaftig.

- Rahel Berkovits, an Orthodox Talmud teacher at Jerusalem's Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies, states that as a result of such changes in Haredi and Modern Orthodox Judaism, "Orthodox women have founded and overseen prayer communities, argue cases in rabbinic courts, advise on halachic issues, and dominate in social work activities that are all very associated with the role a rabbi performs, even though these women do not have the official title of rabbi."

- In 2009, Orthodox Rabbi Avi Weiss founded Yeshivat Maharat, a school which, "is dedicated to giving Orthodox women proficiency in learning and teaching Talmud, understanding Jewish law and its application to everyday life as well as the other tools necessary to be Jewish communal leaders. [14]" Those women who graduate from Yeshivat Maharat are given the title of Maharat, which "is an acronym, in Hebrew, for manhigot hilkhatiot, rukhaniot vTorahniot, meaning, someone who is a spiritual leader trained in Torah and the intricacies of Jewish law." [15]. They are then placed in Orthodox Jewish synagogues as "spiritual and halakhic leaders," although not rabbis [16].

See also

- Abraham-Geiger-Kolleg

- Academy for Jewish Religion in New York

- Academy for Jewish Religion in California

- Beth din

- Clergy

- Hebrew College

- Hebrew Union College

- International Institute for Secular Humanistic Judaism

- Jewish Theological Seminary of America

- List of rabbis

- Mashgiach ruchani

- Mashpia

- Posek

- Rabbinical College of America

- Rabbinic literature

- Rebbe

- Reconstructionist Rabbinical College

- Rosh yeshiva

- Semicha

- Synagogue

- Yeshiva

- Yeshiva University

- Yeshivat Chovevei Torah

References

General

- Rabbi, Rabbinate, article in the Encyclopaedia Judaica, 2nd ed., vol. 17, pp. 11–19, Keter Publishing, 2007.

- Aaron Kirchenbaum, Mara de-Atra: A Brief Sketch, Tradition, Vol. 27, No. 4, 1993, pp. 35–40

- Aharon Lichtenstein, The Israeli Chief Rabbinate: A Current Halakhic Perspective, Tradition, Vol. 26, No. 4, 1992, pp. 26–38

- Jeffrey I. Roth, Inheriting the Crown in Jewish Law: The Struggle for Rabbinic Compensation, Tenure and Inheritance Rights, Univ. of South Carolina Press, 2006

- S. Schwarzfuchs, A Concise History of the Rabbinate, Oxford, 1993

Women in Orthodoxy

- Mason Delugoda

- Debra Nussbau, Cohen, Jewish tradition vs. the modern-day female, March 17, 2000, Jewish Telegraphic Agency

- Lauren Gelfond Feldinger, The Next Feminist Revolution, The Jerusalem Post, March 17, 2005

- Moshe Y'chiail Freidman, Women in the Rabbinate, Jewish Observer, 17:8, 1984, 28-29.

- Laurie Goodstein, Causing a Stir, 2 Synagogues Hire Women to Aid Rabbis, February 6, 1998, New York Times

- Jeff Helmreich, Orthodox women moving toward religious leadership, Friday June 6, 1997, Long Island Jewish World

- Marilyn Henry, Orthodox women crossing threshold into synagogue, Jerusalem Post Service, May 15, 1998

- Jonathan Mark, Women Take Giant Step In Orthodox Community: Prominent Manhattan shul hires ‘congregational intern’ for wide-ranging spiritual duties, The Jewish Week December 19, 1997

- Emanuel Rackman, (Women as Rabbis) Suggestions for Alternatives, Judaism , Vol.33, No.1, 1990, p. 66-69.

- Ben Greenberg, Women Orthodox Rabbis: Heresy or Possibility?, First Things, October 2009

- Gil Student, When Values Collide, First Things, September 2009

- Mimi Feigelson, Yeshivah Student, Feminine Gender, Eretz Acheret Magazine

Notes

- ↑ This is evident from the fact that Hillel I, who came from Babylon, did not have the title Rabban prefixed to his name.

- ↑ The title Ribbi too, came into vogue among those who received the laying on of hands at this period, as, for instance, Ribbi Zadok, Ribbi Eliezer ben Jacob, and others, and dates from the time of the disciples of Rabban Johanan ben Zakkai downward. Now the order of these titles is as follows: Ribbi is greater than Rab; Rabban again, is greater than Ribbi; while the simple name is greater than Rabban. Besides the presidents of the Sanhedrin no one is called Rabban.

- ↑ Englishman's Greek Concordance of the New Testament by Wigram, George V.; citing Matthew 26:25, Mark 9:5 and John 3:2 (among others)

- ↑ See Talmud Kidushin daf 30-40

- ↑ http://www.yutorah.org/lectures/lecture.cfm/746702/Rabbi_Hanan_Balk/The_Obligation_to_Respect_the_Wife_of_a_Torah_Scholar_or_a_Talmidat_Chacham

- ↑ http://www.yutorah.org/lectures/lecture.cfm/746702/Rabbi_Hanan_Balk/The_Obligation_to_Respect_the_Wife_of_a_Torah_Scholar_or_a_Talmidat_Chacham

- ↑ See Talmud Kidushin daf 30-40

- ↑ http://www.yutorah.org/lectures/lecture.cfm/746702/Rabbi_Hanan_Balk/The_Obligation_to_Respect_the_Wife_of_a_Torah_Scholar_or_a_Talmidat_Chacham

- ↑ http://www.yutorah.org/lectures/lecture.cfm/746702/Rabbi_Hanan_Balk/The_Obligation_to_Respect_the_Wife_of_a_Torah_Scholar_or_a_Talmidat_Chacham

- ↑ HUC-JIR admissions requirements

- ↑ Ari L. Goldman, Religion Notes, The New York times, Saturday, March 10, 1990

- ↑ Pitchei Teshuvah CM 7:5

- ↑ Shulchan Aruch CM 7:4

- ↑ Maimonides, Melachim 1:6

- ↑ They Called Her Rebbe, the Maiden of Ludmir. Winkler, Gershon, Ed. Et al. Judaica Press, Inc., October 1990.

- ↑ Statistics, Hebrew Union College, Jewish Institute of Religion

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Rabbi Elizabeth Tikvah Sarah, Women rabbis — a new kind of rabbinic leadership?, 2006.

- ↑ Friedman, Moshe Y'chiail, "Women in the Rabbinate", Friedman, Moshe Y'chiail. Jewish Observer, 17:8, 1984, 28-29.

- ↑ "Rabbanit Reclaimed", Hurwitz, Sara. JOFA Journal, VI, 1, 2006, 10-11.

- ↑ Jan 10, 2008 23:50 | Updated Jan 13, 2008 8:48|Jewishworld.Jpost.Com Hartman Institute to ordain women rabbis

- ↑ Copy of Original Certificate MS Word Document

- ↑ "Rabbis, Rebbetzins and Halakhic Advisors", Wolowelsky, Joel B.. Tradition, 36:4, 2002, pp. 54-63.

External links

- Rabbi, Jewishencyclopedia.com

"Rabbi and Rabbinism". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. - A pre-Vatican II Catholic view of the development of the Rabbinical office

"Rabbi and Rabbinism". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1913. - A pre-Vatican II Catholic view of the development of the Rabbinical office

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||