Quebec

| Quebec Québec |

|||||

|

|||||

| Motto: Je me souviens (English: I remember) |

|||||

|

|||||

| Capital | Quebec City | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Largest city | Montreal | ||||

| Largest metro | Greater Montreal | ||||

| Official languages | French[1] | ||||

| Demonym | Québécois(e)[2] Quebecer,[3] | ||||

| Government | |||||

| Lieutenant-Governor | Pierre Duchesne | ||||

| Premier | Jean Charest (Liberal) | ||||

| Federal representation | in Canadian Parliament | ||||

| House seats | 75 | ||||

| Senate seats | 24 | ||||

| Confederation | July 1, 1867 (1st, with ON, NS, NB) | ||||

| Area | Ranked 2nd | ||||

| Total | 1,542,056 km2 (595,391 sq mi) | ||||

| Land | 1,365,128 km2 (527,079 sq mi) | ||||

| Water (%) | 176,928 km2 (68,312 sq mi) (11.5%) | ||||

| Population | Ranked 2nd | ||||

| Total (2010) | 7,886,108 (est.)[4] | ||||

| Density | 5.63 /km2 (14.6 /sq mi) | ||||

| GDP | Ranked 2nd | ||||

| Total (2006) | C$285.158 billion[5] | ||||

| Per capita | C$37,278 (10th) | ||||

| Abbreviations | |||||

| Postal | QC[6] | ||||

| ISO 3166-2 | CA-QC | ||||

| Time zone | UTC−5, −4 | ||||

| Postal code prefix | G, H, J | ||||

| Flower | Blue Flag Iris[7] | ||||

| Tree | Yellow Birch[7] | ||||

| Bird | Snowy Owl[7] | ||||

| Website | www.gouv.qc.ca | ||||

| Rankings include all provinces and territories | |||||

Quebec /kəˈbɛk/ or /kwɪˈbɛk/ (French: Québec [kebɛk] (![]() listen))[8] is a province in east-central Canada.[9][10] It is the only Canadian province with a predominantly French-speaking population and the only one whose sole official language is French at the provincial level. Quebec is Canada's largest province by area and its second-largest administrative division; only the territory of Nunavut is larger. It is bordered to the west by the province of Ontario, James Bay and Hudson Bay, to the north by Hudson Strait and Ungava Bay, to the east by the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador and New Brunswick. It is bordered on the south by the U.S. states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York. It also shares maritime borders with Nunavut, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia.

listen))[8] is a province in east-central Canada.[9][10] It is the only Canadian province with a predominantly French-speaking population and the only one whose sole official language is French at the provincial level. Quebec is Canada's largest province by area and its second-largest administrative division; only the territory of Nunavut is larger. It is bordered to the west by the province of Ontario, James Bay and Hudson Bay, to the north by Hudson Strait and Ungava Bay, to the east by the Gulf of Saint Lawrence and the provinces of Newfoundland and Labrador and New Brunswick. It is bordered on the south by the U.S. states of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York. It also shares maritime borders with Nunavut, Prince Edward Island, and Nova Scotia.

Quebec is the second most populous province, after Ontario. Most inhabitants live in urban areas near the Saint Lawrence River between Montreal and Quebec City, the capital. English-speaking communities and English-language institutions are concentrated in the west of the island of Montreal but are also significantly present in the Outaouais, the Eastern Townships, and Gaspé regions. The Nord-du-Québec region, occupying the northern half of the province, is sparsely populated and inhabited primarily by Aboriginal peoples.[11]

Sovereignty plays a large role in the politics of Quebec, and the official opposition social democratic Parti Québécois advocates national sovereignty for the province and secession from Canada. Sovereignist governments have held referendums on independence in 1980 and 1995; both were voted down by voters, the latter defeated by a very narrow margin. In 2006, the Canadian House of Commons passed a symbolic motion recognizing the "Québécois as a nation within a united Canada."[12][13]

While the province's substantial natural resources have long been the mainstay of its economy, sectors of the knowledge economy such as aerospace, information and communication technologies, biotechnology and the pharmaceutical industry also play leading roles. These many industries have all contributed to helping Quebec become the second most economically influential province, second only to Ontario.[14]

Etymology and boundary changes

The name "Quebec", which comes from the Algonquin word kébec meaning "where the river narrows", originally referred to the area around Quebec City where the Saint Lawrence River narrows to a cliff-lined gap. Early variations in the spelling of the name included Québecq (Levasseur, 1601) and Kébec (Lescarbot 1609).[15] French explorer Samuel de Champlain chose the name Québec in 1608 for the colonial outpost he would use as the administrative seat for the French colony of New France.[16]

The Province of Quebec was founded in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 after the Treaty of Paris formally transferred the French colony of Canada[17] to Britain after the Seven Years' War. The proclamation restricted the province to an area along the banks of the Saint Lawrence River. The Quebec Act of 1774 restored the Great Lakes and the Ohio River Valley regions to the province. The Treaty of Versailles, 1783 ceded territories south of the Great Lakes to the United States. After the Constitutional Act of 1791, the territory was divided between Lower Canada (present day Quebec) and Upper Canada (present day Ontario), with each being granted an elected Legislative Assembly. In 1840, these become Canada East and Canada West after the British Parliament unified Upper and Lower Canada into the Province of Canada. This territory was redivided into the Provinces of Quebec and Ontario at Confederation in 1867. Each became one of the first four provinces.

In 1870, Canada purchased Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company. Over the next few decades the Parliament of Canada transferred portions of this territory to Quebec that more than tripled the size of the province.[18] In 1898, the Canadian Parliament passed the first Quebec Boundary Extension Act that expanded the provincial boundaries northward to include the lands of the Cree. This was followed by the addition of the District of Ungava through the Quebec Boundaries Extension Act of 1912 that added the northernmost lands of the aboriginal Inuit to create the modern Province of Quebec. In 1927, the border between Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador was established by the British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Quebec officially disputes this boundary.

Geography

Located in the eastern part of Canada and (from a historical and political perspective) part of Central Canada, Quebec occupies a territory nearly three times the size of France or Texas, most of which is very sparsely populated. Quebec's highest point is Mont D'Iberville, located on the border with Newfoundland and Labrador in the northeastern part of the province.

The Saint Lawrence River has one of the world's largest sustaining large inland Atlantic ports at Montreal (the province's largest city), Trois-Rivières, and Quebec City (the capital). Its access to the Atlantic Ocean and the interior of North America made it the base of early French exploration and settlement in the 17th and 18th centuries. Since 1959, the Saint Lawrence Seaway has provided a navigable link between the Atlantic Ocean and Great Lakes. Northeast of Quebec City, the river broadens into the world's largest estuary, the feeding site of numerous species of whales, fish and sea birds.[19] The river empties into the Gulf of Saint Lawrence. This marine environment sustains fisheries and smaller ports in the Lower Saint Lawrence (Bas-Saint-Laurent), Lower North Shore (Côte-Nord), and Gaspé (Gaspésie) regions of the province.

The most populous physiographic region is the Saint Lawrence Lowland. It extends northeastward from the southwestern portion of the province along the shores of the Saint Lawrence River to the Quebec City region, and includes Anticosti Island, the Mingan Archipelago,[20] and other small islands of the Gulf of St. Lawrence lowland forests ecoregion.[21] Its landscape is low-lying and flat, except for isolated igneous outcrops near Montreal called the Monteregian Hills. Geologically, the lowlands formed as a rift valley about 100 million years ago and are prone to infrequent but significant earthquakes.[22] The most recent layers of sedimentary rock were formed as the seabed of the ancient Champlain Sea at the end of the last ice age about 14,000 years ago.[23] The combination of rich and easily arable soils and Quebec's relatively warm climate make the valley Quebec's most prolific agricultural area. Mixed forests provide most of Canada's maple syrup crop every spring. The rural part of the landscape is divided into narrow rectangular tracts of land that extend from the river and date back to settlement patterns in 17th century New France.

More than 90% of Quebec's territory lies within the Canadian Shield, a rough, rocky terrain sculpted and scraped clean of soil by successive ice ages. It is rich in the forestry, mineral and hydro-electric resources that are a mainstay of the Quebec economy. Primary industries sustain small cities in regions of Abitibi-Témiscamingue, Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean, and Côte-Nord.

In the Labrador Peninsula portion of the Shield, the far northern region of Nunavik includes the Ungava Peninsula and consists of Arctic tundra inhabited mostly by the Inuit. Further south lie the subarctic taiga of the Eastern Canadian Shield taiga ecoregion and the boreal forest of the Central Canadian Shield forests, where spruce, fir, and poplar trees provide raw materials for Quebec's pulp and paper and lumber industries. Although the area is inhabited principally by the Cree, Naskapi, and Innu First Nations, thousands of temporary workers reside at Radisson to service the massive James Bay Hydroelectric Project on the La Grande and Eastmain rivers. The southern portion of the shield extends to the Laurentians, a mountain range just north of Montreal and Quebec City that attracts local and international tourists to ski hills and lakeside resorts.

The Eastern Canadian forests cover the Appalachian Mountains in the eastern portion of the province and on to the Gaspé Peninsula, where they disappear into the Gulf of St. Lawrence. This region sustains a mix of forestry, industry, and tourism based on its natural resources and landscape.

Climate

Quebec has three main climate regions. Southern and western Quebec, including most of the major population centres, have a humid continental climate (Köppen climate classification Dfb) with four distinct seasons having warm to occasionally hot and humid summers and often very cold and snowy winters. The main climatic influences are from western and northern Canada and move eastward, and from the southern and central United States that move northward. Because of the influence of both storm systems from the core of North America and the Atlantic Ocean, precipitation is abundant throughout the year, with most areas receiving more than 1000 mm(40 in) of precipitation, including over 300 centimetres (120 in) of snow in many areas. During the summer, severe weather patterns (such as tornadoes and severe thunderstorms) occur occasionally.

Most of central Quebec has a subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc). Winters are long, very cold, and snowy, and among the coldest in eastern Canada, while summers are warm but very short due to the higher latitude and the greater influence of Arctic air masses. Precipitation is also somewhat less than farther south, except at some of the higher elevations.

The northern regions of Quebec have an arctic climate (Köppen ET), with very cold winters and short, much cooler summers. The primary influences in this region are the Arctic Ocean currents (such as the Labrador Current) and continental air masses from the High Arctic.

History

First Nations and European exploration

At the time of first European contact and later colonization, Algonquian, Iroquoian and Inuit tribes were the peoples who inhabited what is now Quebec. Their lifestyles and cultures reflected the land on which they lived. Seven Algonquian groups lived nomadic lives based on hunting, gathering, and fishing in the rugged terrain of the Canadian Shield: (James Bay Cree, Innu, Algonquins) and Appalachian Mountains (Mi'kmaq, Abenaki). St. Lawrence Iroquoians lived more settled lives, planting squash and maize in the fertile soils of the St. Lawrence Valley. The Inuit continue to fish and hunt whale and seal in the harsh Arctic climate along the coasts of Hudson and Ungava Bay. These people traded fur and food and sometimes warred with each other.

Basque whalers and fishermen traded furs with Saguenay natives throughout the 16th century.[24] The first French explorer to reach Quebec was Jacques Cartier, who planted a cross in 1534 at either Gaspé or Old Fort Bay on the Lower North Shore. He sailed into the St. Lawrence River in 1535 and established an ill-fated colony near present-day Quebec City at the site of Stadacona, a village of the St. Lawrence Iroquoians. Linguists and archeologists have determined these people were distinct from the Iroquoian nations encountered by later French and Europeans, such as the five nations of the Haudenosaunee. Their language was Laurentian, one of the Iroquoian family. By the late 16th century, they had disappeared from the St. Lawrence Valley.

New France

Around 1522 - 1523, the Italian navigator Giovanni da Verrazzano persuaded King Francis I of France to commission an expedition to find a western route to Cathay (China). Late in 1523, Verrazzano set sail in Dieppe, crossing the Atlantic on a small caravel with 53 men. After exploring the coast of the present-day Carolinas early the following year, he headed north along the coast, eventually anchoring in the Narrows of New York Bay. The first European to discover the site of present-day New York, he named it Nouvelle-Angoulême in honour of the king, the former count of Angoulême. Verrazzano's voyage convinced the king to seek to establish a colony in the newly discovered land. Verrazzano gave the names Francesca and Nova Gallia to that land between New Spain (Mexico) and English Newfoundland.

In 1534, Jacques Cartier planted a cross in the Gaspé Peninsula and claimed the land in the name of King Francis I. It was the first province of New France. However, initial French attempts at settling the region met with failure. French fishing fleets, however, continued to sail to the Atlantic coast and into the St. Lawrence River, making alliances with First Nations that would become important once France began to occupy the land. French merchants soon realized the St. Lawrence region was full of valuable fur-bearing animals, especially the beaver, an important commodity as the European beaver had almost been driven to extinction. Eventually, the French crown decided to colonize the territory to secure and expand its influence in America.

Samuel de Champlain was part of a 1603 expedition from France that travelled into the St. Lawrence River. In 1608, he returned as head of an exploration party and founded Quebec City with the intention of making the area part of the French colonial empire. Champlain's Habitation de Quebec, built as a permanent fur trading outpost, was where he would forge a trading, and ultimately a military alliance, with the Algonquin and Huron nations. Natives traded their furs for many French goods such as metal objects, guns, alcohol, and clothing.

Hélène Desportes, born July 7, 1620, to the French habitants (settlers) Pierre Desportes and his wife Françoise Langlois, was the first child of European descent born in Quebec.

From Quebec, coureurs des bois, voyageurs and Catholic missionaries used river canoes to explore the interior of the North American continent, establishing fur trading forts on the Great Lakes (Étienne Brûlé 1615), Hudson Bay (Radisson and Groseilliers 1659–60), Ohio River and Mississippi River (La Salle 1682), as well as the Prairie River and Missouri River (de la Verendrye 1734–1738).

After 1627, King Louis XIII of France introduced the seigneurial system and forbade settlement in New France by anyone other than Roman Catholics. Sulpician and Jesuit clerics founded missions in Trois-Rivières (Laviolette) and Montreal or Ville-Marie (Paul Chomedey de Maisonneuve and Jeanne Mance) to convert New France's Huron and Algonkian allies to Catholicism. The seigneurial system of governing New France also encouraged immigration from the motherland.

New France became a Royal Province in 1663 under King Louis XIV of France with a Sovereign Council that included intendant Jean Talon. This ushered in a golden era of settlement and colonization in New France, including the arrival of les "Filles du Roi". The population grew from about 3,000 to 60,000 people between 1666 and 1760.[26] Colonists built farms on the banks of St. Lawrence River and called themselves "Canadiens" or "Habitants". The colony's total population was limited, however, by a winter climate much harsher than that of France, by the spread of diseases, and by the refusal of the French crown to allow Huguenots, or French Protestants, to settle there. The population of New France lagged far behind that of the Thirteen Colonies to the south, leaving it vulnerable to attack.

Many donnes (the assistants to the Jesuit priests) tried to convert the natives of New France during the 1600's. One Donne, Eustache Lambert, helped the natives destroy a rival tribe, but ultimately failed.

Seven Years' War and capitulation of New France

In 1753 France began building a series of forts in the contested Ohio Country. They refused to leave after being notified by the British Governor, and in 1754 George Washington launched an attack on the French Fort Duquesne (now Pittsburgh) in the Ohio Valley in an attempt to enforce the British claim to the territory. This frontier battle set the stage for the French and Indian War in North America. By 1756, France and Britain were battling the Seven Years' War worldwide. In 1758, the British mounted an attack on New France by sea and took the French fort at Louisbourg.

On September 13, 1759, General James Wolfe defeated General Louis-Joseph de Montcalm on the Plains of Abraham outside Quebec City. With the exception of the small islands of Saint Pierre and Miquelon, located off the coast of Newfoundland, France ceded its North American possessions to Great Britain through the Treaty of Paris (1763) in favor of the island of Guadeloupe for its then-lucrative sugar cane industry. The British Royal Proclamation of 1763 renamed Canada (part of New France) as the Province of Quebec.

At roughly the same time as the northern parts of New France were being turned over to the British and beginning their evolution towards modern day Quebec and Canada, the southern parts of New France (Louisiana) were signed over to Spain by the Treaty of Fontainebleau of 1762. As a result of double cession of Quebec to the British and Louisiana to the Spanish, the first French colonial empire collapsed, with France being expelled almost entirely from the continental Americas, left only with a rump set of colonies restricted principally to scattered territories and islands in the Caribbean.

After the capture of New France the British implemented a plan to control the French and entice them to assimilate into the British way of life. They prevented Catholics from holding public office and forbade the recruitment of priests and brothers, effectively shutting down Quebec's schools and colleges. This first British policy of assimilation (1763–1774) was deemed a failure. Both the demands in the petitions of the Canadiens' élites and the recommendations by Governor Guy Carleton played an important role in persuading London to drop the assimilation scheme, but the looming American revolt was certainly also a factor as the British were fearful that the French-speaking population of Quebec would side with the rebellious Thirteen Colonies to the south, especially if France allied with the Americans as it appeared it would.

Quebec Act and the American Revolution

In 1774, the British Parliament passed the Quebec Act through which the Quebec people obtained their first Charter of Rights. This paved the way to later official recognition of the French language and French culture. The act also allowed Canadiens to maintain French civil law and sanctioned freedom of religion, allowing the Roman Catholic Church to remain, one of the first cases in history of state-sanctioned freedom of practice. Further, it restored the Ohio Valley to Quebec, reserving the territory for the fur trade.

The Quebec Act, while designed to placate one North American colony, had the opposite effect among the Americans to the south. The act was among the so called "Intolerable Acts" that infuriated the American colonists, leading them to the armed insurrection of the American Revolution.

On June 27, 1775, General George Washington decided to attempt an invasion of Canada by the American Continental Army to wrest Quebec and the St. Lawrence River from the British. A force led by Brigadier General Richard Montgomery headed north from Fort Ticonderoga along Lake Champlain and up the St. Lawrence River valley. Meanwhile, Colonel Benedict Arnold persuaded Washington to have him lead a separate expedition through the Maine wilderness. The two forces joined at Quebec City, but were defeated at the Battle of Quebec in December 1775. Prior to this battle Montgomery (killed in the battle) had met with some early successes but the invasion failed when British reinforcements came down the St. Lawrence in May 1776 and the Battle of Trois-Rivières turned into a disaster for the Americans. The army withdrew back to Ticonderoga.

Although some help was given to the Americans by the locals, Governor Carleton punished American sympathizers and public support of the American cause came to an end.

The American Revolutionary War was ultimately successful in winning independence for the Thirteen Colonies. In the Treaty of Paris (1783), the British ceded their territory south of the Great Lakes to the newly formed United States of America.

At the end of the war, 50,000 British Loyalists from America came to Canada and settled amongst a population of 90,000 French people. Many of the loyalist refugees settled into the Eastern Townships of Quebec, in the area of Sherbrooke, Drummondville and Lennoxville.

Patriotes' Rebellion in Lower Canada

In 1837 residents of Lower Canada, led by Louis-Joseph Papineau and Robert Nelson, formed an armed resistance group to seek an end to the unilateral control of the British governors.[27] They made a Declaration of Rights with equality for all citizens without discrimination and a Declaration of Independence of Lower-Canada in 1838.[28] Their actions resulted in rebellions in both Lower and Upper Canada. An unprepared British Army had to raise militia force, the rebel forces scored a victory in Saint-Denis but were soon defeated. The British army burned the Church of St-Eustache, killing the rebels who were hiding within it. The bullet and cannonball marks on the walls of the church are still visible to this day.

After the rebellions, Lord Durham was asked to undertake a study and prepare a report on the matter and to offer a solution for the British Parliament to assess.

The final report recommended that the two provinces of Upper and Lower Canada be united, and that the French speaking population of Lower Canada be assimilated into British culture. Durham's second recommendation was the implementation of responsible government across the colonies. Following Durham's Report, the British government merged the two colonial provinces into one Province of Canada in 1840 with the Act of Union.

However, the political union proved contentious. Reformers in both Canada West (formerly Upper Canada) and Canada East (formerly Lower Canada) worked to repeal limitations on the use of the French language in the Legislature. The two colonies remained distinct in administration, election, and law.

In 1848, Baldwin and LaFontaine, allies and leaders of the Reformist party, were asked by Lord Elgin to form an administration together under the new policy of responsible government. The French language subsequently regained legal status in the Legislature.

Canadian Confederation

In the 1860s, the delegates from the colonies of British North America (Canada, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, and Newfoundland) met in a series of conferences to discuss self-governing status for a new confederation. The first Charlottetown Conference took place in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island followed by the Quebec Conference in Quebec City which led to a delegation going to London, Britain, to put forth a proposal for a national union.

As a result of those deliberations, in 1867 the Parliament of the United Kingdom passed the British North America Act, providing for the Confederation of most of these provinces. The former Province of Canada was divided into its two previous parts as the provinces of Ontario (Upper Canada) and Quebec (Lower Canada). New Brunswick and Nova Scotia joined Ontario and Quebec in the new Dominion of Canada.

Quiet Revolution

The conservative government of Maurice Duplessis and his Union Nationale dominated Quebec politics from 1944 to 1959 with the support of the Roman Catholic church. Pierre Elliot Trudeau and other liberals formed an intellectual opposition to Duplessis's regime, setting the groundwork for the Quiet Revolution under Jean Lesage's Liberals. The Quiet Revolution was a period of dramatic social and political change that saw the decline of Anglo supremacy in the Quebec economy, the decline of the Roman Catholic Church's influence, the nationalization of hydro-electric companies under Hydro-Québec and the emergence of a pro-sovereignty movement under former Liberal minister René Lévesque.

Front de libération du Québec

Beginning in 1963, a terrorist group that became known as the Front de libération du Québec (FLQ) launched a decade of bombings, robberies and attacks[29] directed primarily at English institutions, resulting in at least five deaths. In 1970, their activities culminated in events referred to as the October Crisis when James Cross, the British trade commissioner to Canada, was kidnapped along with Pierre Laporte, a provincial minister and Vice-Premier.[30] Laporte was strangled with his own rosary beads a few days later. In their published Manifesto, the terrorists stated: "In the coming year Bourassa will have to face reality; 100,000 revolutionary workers, armed and organized."

At the request of Premier Robert Bourassa, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invoked the War Measures Act. In addition, the Quebec Ombudsman[31] Louis Marceau was instructed to hear complaints of detainees and the Quebec government agreed to pay damages to any person unjustly arrested (only in Quebec). On February 3, 1971, John Turner, the Minister of Justice of Canada, reported that 497 persons had been arrested throughout Canada under the War Measures Act,[32] of whom 435 had been released. The other 62 were charged, of which 32 were crimes of such seriousness that a Quebec Superior Court judge refused them bail. The crisis ended a few weeks after the death of Pierre Laporte at the hands of his captors. The fallout of the crisis marked the zenith and twilight of the FLQ which lost membership and public support.

Parti Québécois and national unity

In 1977, the newly elected Parti Québécois government of René Lévesque introduced the Charter of the French Language. Often known as Bill 101, it defined French as the only official language of Quebec in areas of provincial jurisdiction.

Lévesque and his party had run in the 1970 and 1973 Quebec elections under a platform of separating Quebec from the rest of Canada. The party failed to win control of Quebec's National Assembly both times — though its share of the vote increased from 23% to 30% — and Lévesque was defeated both times in the riding he contested. In the 1976 election, he softened his message by promising a referendum (plebiscite) on sovereignty-association rather than outright separation, by which Quebec would have independence in most government functions but share some other ones, such as a common currency, with Canada. On November 15, 1976, Lévesque and the Parti Québécois won control of the provincial government for the first time. The question of sovereignty-association was placed before the voters in the 1980 Quebec referendum. During the campaign, Pierre Trudeau promised that a vote for the "no" side was a vote for reforming Canada. Trudeau advocated the patriation of Canada's Constitution from the United Kingdom. The existing constitutional document, the British North America Act, could only be amended by the United Kingdom Parliament upon a request by the Canadian parliament.

Sixty percent of the Quebec electorate voted against the proposition. Polls showed that the overwhelming majority of English and immigrant Quebecers voted against, and that French Quebecers were almost equally divided, with older voters less in favour and younger voters more in favour. After his loss in the referendum, Lévesque went back to Ottawa to start negotiating a new constitution with Trudeau, his minister of Justice Jean Chrétien and the nine other provincial premiers. Lévesque insisted Quebec be able to veto any future constitutional amendments. The negotiations quickly reached a stand-still.

Then on the night of November 4, 1981 (widely known in Quebec as La nuit des longs couteaux and in the rest of Canada as the "Kitchen Accord") Federal Justice Minister Jean Chrétien met with all of the provincial premiers except René Lévesque to sign the document that would eventually become the new Canadian constitution. The next morning, they presented the "fait accompli" to Lévesque. Lévesque refused to sign the document and returned to Quebec. In 1982, Trudeau had the new constitution approved by the British Parliament, with Quebec's signature still missing (a situation that persists to this day). The Supreme Court of Canada confirmed Trudeau's assertion that every province's approval is not required to amend the constitution. Quebec is the only province not to have assented to the patriation of the Canadian constitution in 1982.[33]

In subsequent years, two attempts were made to gain Quebec's approval of the constitution. The first was the Meech Lake Accord of 1987, which was finally abandoned in 1990 when the province of Manitoba did not pass it within the established deadline. (Newfoundland premier Clyde Wells had expressed his opposition to the accord, but, with the failure in Manitoba, the vote for or against Meech never took place in his province.) This led to the formation of the sovereignist Bloc Québécois party in Ottawa under the leadership of Lucien Bouchard, who had resigned from the federal cabinet. The second attempt, the Charlottetown Accord of 1992, was rejected by 56.7% of all Canadians and 57% of Quebecers. This result caused a split in the Quebec Liberal Party that led to the formation of the new Action démocratique (Democratic Action) party led by Mario Dumont and Jean Allaire.

On October 30, 1995, with the Parti Québécois back in power since 1994, a second referendum on sovereignty took place. This time, it was rejected by a slim majority (50.6% NO to 49.4% YES); a clear majority of French-speaking Quebecers voted in favour of sovereignty.

The referendum was enshrouded in controversy. Federalists complained that an unusually high number of ballots had been rejected in pro-federalist areas, notably in the largely Jewish and Greek riding of Chomedey (11.7 % or 5,500 of its ballots were spoiled, compared to 750 or 1.7% in the general election of 1994) although Quebec's chief electoral officer found no evidence of outright fraud. The federal government was accused of not respecting provincial laws with regard to spending during referendums (leading to a corruption scandal that would become public a decade later, greatly damaging the Liberal Party's standing), and of having accelerated the naturalization of immigrants in Quebec before the referendum in order that they could vote, as naturalized citizens were believed more likely to vote no. (43,850 immigrants were naturalized in 1995, whereas the average number between 1988 and 1998 was 21,733.)

The same night of the referendum, an angry Jacques Parizeau, then premier and leader of the "Yes" side, declared that the loss was because of "Money and the ethnic vote". Parizeau resigned over public outrage and as per his commitment to do so in case of a loss. Lucien Bouchard became Quebec's new premier in his place.

Federalists accused the sovereignist side of asking a vague, overly complicated question on the ballot. Its English text read as follows:

Do you agree that Québec should become sovereign after having made a formal offer to Canada for a new economic and political partnership within the scope of the bill respecting the future of Québec and of the agreement signed on June 12, 1995?

After winning the next election in 1998, Bouchard retired from politics in 2001. Bernard Landry was then appointed leader of the Parti Québécois and premier of Quebec. In 2003, Landry lost the election to the Quebec Liberal Party and Jean Charest. Landry stepped down as PQ leader in 2005, and in a crowded race for the party leadership, André Boisclair was elected to succeed him. He also resigned after the renewal of the Quebec Liberal Party's government in the 2007 general election and the Parti Québécois becoming the second opposition party, behind the Action Démocratique. The PQ has promised to hold another referendum should it return to government.

Statut particulier ("special status")

Given the province's heritage and the preponderance of French (unique among the Canadian provinces), there is an ongoing debate in Canada regarding the unique status (statut particulier) of Quebec and its people, wholly or partially. Prior attempts to amend the Canadian constitution to acknowledge Quebec as a 'distinct society' – referring to the province's uniqueness within Canada regarding law, language, and culture – have been unsuccessful; however, the federal government under Prime Minister Jean Chrétien would later endorse recognition of Quebec as a "unique society".[34]

On October 30, 2003, the National Assembly of Quebec voted unanimously to affirm "that the Quebecers form a nation".[35] On November 27, 2006, the House of Commons passed a symbolic motion moved by Prime Minister Stephen Harper declaring that "this House recognize[s] that the Québécois form a nation within a united Canada."[36][37][38] However, there is considerable debate and uncertainty over what this means.[39][40]

At present, nationalism plays a large role in the politics of Quebec, with all three major provincial political parties seeking greater autonomy and recognition of Quebec's unique status. In recent years, much attention has been devoted to examining and defining the nature of Quebec's association with the rest of Canada. Currently, the population is roughly divided between two political visions for the future of their province. About 40% of Quebecers support the idea of either full sovereignty (completely separating from Canada and forming an independent state) or of sovereignty-association with the rest of Canada, which would entail the sharing of some institutional and governmental responsibilities with the federal government in a manner similar to how the European Union shares a common currency and various other services. On the other hand, a slightly larger faction of Quebecers are satisfied with the status quo and wish their province to remain within a united Canadian federation.

Fundamental Values of Quebec Society

On February 8, 2007, Quebec Premier Jean Charest announced the setting up of a Commission tasked with consulting Quebec Society on the matter of arrangements regarding cultural diversity. The Premier's press release[41] reasserted the Three Fundamental Values of Quebec Society:

- Equality between Men and Women

- Primacy of the French Language

- Separation of State and Religion

[These Values] are not subject to any arrangement. They cannot be subordinated to any other principle.[42]

Furthermore, Quebec is a free and democratic society that abides by the Rule of Law[43]

Quebec Society bases its cohesion and specificity on a set of statements, a few notable examples of which include:

- The Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms[44]

- The Charter of the French Language[45]

- The Civil Code of Quebec[46]

Demographics

At 1.74 children per woman,[47] Quebec's 2008 fertility rate is above the Canada-wide rate of 1.59,[48] and has increased for five consecutive years. However, it is still below the replacement fertility rate of 2.1. This contrasts with its fertility rates before 1960, which were among the highest of any industrialized society. Although Quebec is home to only 23.9% of the population of Canada, the number of international adoptions in Quebec is the highest of all provinces of Canada. In 2001, 42% of international adoptions in Canada were carried out in Quebec.

| Year | Population | Five-year % change |

Ten-year % change |

Rank among provinces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1851 | 892,061 | n/a | n/a | 2 |

| 1861 | 1,111,566 | n/a | 24.6 | 2 |

| 1871 | 1,191,516 | n/a | 7.2 | 2 |

| 1881 | 1,359,027 | n/a | 14.1 | 2 |

| 1891 | 1,488,535 | n/a | 9.5 | 2 |

| 1901 | 1,648,898 | n/a | 10.8 | 2 |

| 1911 | 2,005,776 | n/a | 21.6 | 2 |

| 1921 | 2,360,665 | n/a | 17.8 | 2 |

| 1931 | 2,874,255 | n/a | 21.8 | 2 |

| 1941 | 3,331,882 | n/a | 15.9 | 2 |

| 1951 | 4,055,681 | n/a | 21.8 | 2 |

| 1956 | 4,628,378 | 14.1 | n/a | 2 |

| 1961 | 5,259,211 | 13.6 | 29.7 | 2 |

| 1966 | 5,780,845 | 9.9 | 24.9 | 2 |

| 1971 | 6,027,765 | 4.3 | 14.6 | 2 |

| 1976 | 6,234,445 | 3.4 | 7.8 | 2 |

| 1981 | 6,438,403 | 3.3 | 6.8 | 2 |

| 1986 | 6,532,460 | 1.5 | 4.8 | 2 |

| 1991 | 6,895,963 | 5.6 | 7.1 | 2 |

| 1996 | 7,138,795 | 3.5 | 9.3 | 2 |

| 2001 | 7,237,479 | 1.4 | 5.0 | 2 |

| 2006 | 7,546,131 | 4.3 | 5.7 | 2 |

Source: Statistics Canada[49][50]

Origins in this table are self-reported and respondents were allowed to give more than one answer.

| Ethnic origin | Population | Percent |

|---|---|---|

| Canadian | 4,474,115 | 60.1% |

| French | 2,151,655 | 28.9% |

| Irish | 406,085 | 5.5% |

| Italian | 299,655 | 4.0% |

| English | 245,155 | 3.3% |

| North American Indian | 219,815 | 3.0% |

| Scottish | 202,515 | 2.7% |

| Québécois | 140,075 | 1.9% |

| German | 131,795 | 1.8% |

| Chinese | 91,900 | 1.2% |

| Haitian | 91,435 | 1.2% |

| Spanish | 72,090 | 1.0% |

| Jewish | 71,380 | 1.0% |

| Greek | 65,985 | 0.9% |

| Polish | 62,800 | 0.8% |

| Lebanese | 60,950 | 0.8% |

| Portuguese | 57,445 | 0.8% |

| Belgian | 43,275 | 0.6% |

| East Indian | 41,600 | 0.6% |

| Romanian | 40,320 | 0.5% |

| Russian | 40,155 | 0.5% |

| Moroccan | 36,700 | 0.5% |

| American | 36,695 | 0.5% |

| Métis | 36,280 | 0.5% |

| Vietnamese | 33,815 | 0.5% |

Percentages are calculated as a proportion of the total number of respondents (7,435,905) and may total more than 100% due to dual responses.

Only groups with 0.5% or more of respondents are shown.[51]

The 2006 census counted a total aboriginal population of 108,425 (1.5%) including 65,085 North American Indians (0.9%), 27,985 Métis (0.4%), and 10,950 Inuit (0.15%). It should be noted however, that there is a significant undercount, as many of the biggest Indian bands regularly refuse to participate in Canadian censuses for political reasons regarding the question of aboriginal sovereignty. In particular, the largest Mohawk Iroquois reserves (Kahnawake, Akwesasne and Kanesatake) were not counted.

Percentages are calculated as a proportion of the total number of respondents (7,435,905)[52]

Nearly 9% of the population of Quebec belongs to a visible minority group. This is a lower percentage than that of British Columbia, Ontario and Alberta, but higher than that of the other six provinces. Most visible minorities in Quebec live in or near Montreal.

| Visible minority | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Total visible minority population | 654,355 | 8.8% |

| Black | 188,070 | 2.5% |

| Arab | 109,020 | 1.5% |

| Latin American | 89,505 | 1.2% |

| Chinese | 79,830 | 1.1% |

| South Asian | 72,845 | 1.0% |

| Southeast Asian | 50,455 | 0.7% |

Percentages are calculated as a proportion of the total number of respondents (7,435,905).

Only groups with more than 0.5% of respondents are shown[53]

Quebec is unique among the provinces in its overwhelmingly Roman Catholic population. This is a legacy of colonial times when only Roman Catholics were permitted to settle in New France. The 2001 census showed the population to be 90.3% Christian (in contrast to 77% for the whole country) with 83.4% Catholic Christian (including 83.2% Roman Catholic); 4.7% Protestant Christian (including 1.2% Anglican, 0.7% United Church; and 0.5% Baptist); 1.4% Orthodox Christian (including 0.7% Greek Orthodox); and 0.8% other Christian; as well as 1.5% Muslim; 1.3% Jewish; 0.6% Buddhist; 0.3% Hindu; and 0.1% Sikh. An additional 5.8% of the population said they had no religious affiliation (including 5.6% who stated that they had no religion at all).

Percentages are calculated as a proportion of the total number of respondents (7,125,580)[54]

Language

The official language of Quebec is French. Quebec is the only Canadian province whose population is mainly francophone, constituting 80.1% (5,877,660) of the population giving a singular response regarding their first language according to the 2006 Census.[55] About 95% of the people reported being able to speak French, either as their first or second language, and for some as a third language.

English is not designated an official language by Quebec law.[56] However, both English and French are required by the Constitution Act, 1867 for the enactment of laws and regulations and any person may use English or French in the National Assembly and the courts of Quebec. The books and records of the National Assembly must also be kept in both languages.[57][58]

In 2006, 575,560 (7.7% of population) people in Quebec declared English to be their mother tongue, 744,430 (10.0%) mostly used English as their home language, and 918,955 (12.9% according to the 2001 Census) reported English to be their First Official language spoken.[59][60][61] The English-speaking community or Anglophones are entitled to services in English in the areas of justice, health, and education;[56] services in English are offered in municipalities in which more than half the residents have English as their mother tongue.

Allophones, whose mother tongue is neither French nor English, make up 11.9% (886,280) of the population.[55]

There is a considerable number of people that consider themselves to be bilingual (having a knowledge of French and English). In Quebec, about 40.6% (3,017,860) of the population are bilingual; on the island of Montreal, this proportion grows to 60.0% (1,020,760). Quebec has the highest proportion of bilinguals of any Canadian province. The proportion in the rest of Canada is only about 10.2% (2,430,990) of the population having a knowledge of both of the country's official languages. Overall, 17.4% (5,448,850) of Canadians report being bilingual.[62][63]

Languages other than French on commercial signs are only permitted if French is given marked prominence. While this law is now accepted by most of the population, ongoing arguments on its application has led to some conflicts from time to time..

French place names in Canada retain their accents in English text. Legitimate exceptions are Montreal and Quebec, although they are not listed as names of pan-Canadian significance. Quebec province, however, is on the list and is shown without an accent in English. However, the accented forms are increasingly evident in some publications. The Canadian Style states that Montréal and Québec (the city) must retain their accents in English federal documents.

Of the 7,546,131 population counted by the 2006 census, 7,435,905 people completed the section about language. Of these, 7,339,495 gave singular responses to the question regarding their first language. The languages most commonly reported were the following:

| Language | Number of native speakers |

Percentage of singular responses |

|---|---|---|

| French | 5,877,660 | 80.1% |

| English | 575,555 | 7.8% |

| Italian | 124,820 | 1.7% |

| Spanish | 108,790 | 1.5% |

| Arabic | 108,105 | 1.5% |

| Chinese | 63,415 | 0.9% |

| Berber | 41,845 | 0.6% |

| Portuguese | 34,710 | 0.5% |

| Romanian | 27,180 | 0.4% |

| Vietnamese | 25,370 | 0.3% |

| Russian | 19,275 | 0.3% |

| German | 17,855 | 0.2% |

| Polish | 17,305 | 0.2% |

| Armenian | 15,520 | 0.2% |

| Persian | 14,655 | 0.2% |

| Creole | 14,060 | 0.2% |

| Cree | 13,340 | 0.2% |

| Punjabi | 11,905 | 0.2% |

| Tagalog (Filipino) | 11,785 | 0.2% |

| Tamil | 11,570 | 0.1% |

| Hindi | 9,685 | 0.1% |

| Bengali | 9,660 | 0.1% |

| Inuktitut | 9,615 | 0.1% |

| Montagnais-Naskapi | 9,335 | 0.1% |

| Khmer (Cambodian) | 8,250 | 0.1% |

| Yiddish | 8,225 | 0.1% |

| Hungarian (Magyar) | 7,750 | 0.1% |

| Marathi | 6,050 | 0.1% |

| Turkish | 5,865 | 0.1% |

| Ukrainian | 5,395 | 0.1% |

| Atikamekw | 5,245 | 0.1% |

| Bulgarian | 5,215 | 0.1% |

| Lao | 4,785 | 0.1% |

| Hebrew | 4,110 | 0.1% |

| Korean | 3,970 | 0.1% |

| Dutch | 3,620 | 0.05% |

Numerous other languages were also counted, but only languages with more than 3,000 native speakers are shown.

(Figures shown are for the number of single language responses and the percentage of total single-language responses)[64]

Economy

The St. Lawrence River Valley is a fertile agricultural region, producing dairy products, fruit, vegetables, foie gras, maple syrup (of which Quebec is the world's largest producer), fish, and livestock.

North of the St. Lawrence River Valley, the territory of Quebec has significant resources in its coniferous forests, lakes, and rivers—pulp and paper, lumber, and hydroelectricity (of which Quebec is also the world's largest producer through Hydro-Québec)[65][66] are still some of the province's most important industries.

There is a significant concentration of high-tech industries around Montreal, including aerospace companies such as aircraft manufacturer Bombardier, the jet engine company Pratt & Whitney, the flight simulator builder CAE, defence contractor Lockheed Martin, Canada and communications company Bell Canada. In the video game industry, large video game companies such as Electronic Arts and Ubisoft have studios in Montreal.[67]

Government

The Lieutenant Governor represents Queen Elizabeth II as head of state. The head of government is the Premier (called premier ministre in French) who leads the largest party in the unicameral National Assembly or Assemblée Nationale, from which the Council of Ministers is appointed.

Until 1968, the Quebec legislature was bicameral, consisting of the Legislative Council and the Legislative Assembly. In that year the Legislative Council was abolished, and the Legislative Assembly was renamed the National Assembly. Quebec was the last province to abolish its legislative council.

The government of Quebec awards an order of merit called the National Order of Quebec. It is inspired in part by the French Legion of Honour. It is conferred upon men and women born or living in Quebec (but non-Quebecers can be inducted as well) for outstanding achievements.

Administrative subdivisions

Quebec has subdivisions at the regional, supralocal and local levels. Excluding administrative units reserved for Aboriginal lands, the primary types of subdivision are:

At the regional level:

- 17 administrative regions.

At the supralocal level:

- 86 regional county municipalities or RCMs (municipalités régionales de comté, MRC);

- 2 metropolitan communities (communautés métropolitaines).

At the local level:

- 1,117 local municipalities of various types;

- 11 agglomerations (agglomérations) grouping 42 of these local municipalities;

- within 8 local municipalities, 45 boroughs (arrondissements).

Population centres

| Largest Metropolitan Areas in Quebec[68] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Core City | Administrative Region | Pop. | Rank | Core City | Administrative Region | Pop. | ||||

| 1 | Montreal | Montréal | 3,635,571 | 16 | Rouyn-Noranda | Abitibi-Témiscamingue | 39,924 | ||||

| 2 | Quebec City | Capitale-Nationale | 715,515 | 17 | Salaberry-de-Valleyfield | Montérégie | 39,672 | ||||

| 3 | Gatineau | Outaouais | 283,959 | 18 | Alma | Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean | 32,603 | ||||

| 4 | Sherbrooke | Estrie | 186,952 | 19 | Val-d'Or | Abitibi-Témiscamingue | 32,288 | ||||

| 5 | Saguenay | Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean | 151,643 | 20 | Saint-Georges | Chaudière-Appalaches | 31,364 | ||||

| 6 | Trois-Rivières | Mauricie | 141,529 | 21 | Baie-Comeau | Côte-Nord | 29,808 | ||||

| 7 | Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu | Montérégie | 87,492 | 22 | Sept-Îles | Côte-Nord | 27,827 | ||||

| 8 | Drummondville | Centre-du-Québec | 78,108 | 23 | Thetford Mines | Chaudière-Appalaches | 26,107 | ||||

| 9 | Granby | Montérégie | 68,352 | 24 | Rivière-du-Loup | Bas-Saint-Laurent | 24,570 | ||||

| 10 | Shawinigan | Mauricie | 56,434 | 25 | Amos | Abitibi-Témiscamingue | 17,918 | ||||

| 11 | Saint-Hyacinthe | Montérégie | 55,823 | 26 | Matane | Bas-Saint-Laurent | 16,438 | ||||

| 12 | Victoriaville | Centre-du-Québec | 48,893 | 27 | La Tuque | Mauricie | 15,293 | ||||

| 13 | Sorel-Tracy | Montérégie | 48,295 | 28 | Dolbeau-Mistassini | Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean | 14,546 | ||||

| 14 | Rimouski | Bas-Saint-Laurent | 46,807 | 29 | Cowansville | Montérégie | 12,666 | ||||

| 15 | Joliette | Lanaudière | 43,595 | 30 | Lachute | Laurentides | 11,832 | ||||

| Canada 2006 Census | |||||||||||

Sports teams

- Canadian Football League

- Montreal Alouettes

- Can-Am League

- Quebec Capitales

- Premier Basketball League

- Quebec Kebs

- United Soccer Leagues

- Montreal Impact

- Canadian Women's Hockey League

- Montreal Stars

- Quebec Phoenix

Former sports teams

- National Hockey League

- Quebec Nordiques (moved to Denver, Colorado and are now the Colorado Avalanche)

- Quebec Bulldogs (moved to Hamilton, Ontario and became the Hamilton Tigers for the rest of the team's existence)

- Montreal Maroons (defunct)

- Montreal Wanderers (defunct)

- Major League Baseball

- Montreal Expos (moved to Washington, D.C. and are now the Washington Nationals)

- American Hockey League

- Quebec Citadelles (merged with the Hamilton Bulldogs)

- Quebec Aces (moved to Richmond, Virginia and became the Richmond Robins for the rest of the team's existence)

- Sherbrooke Canadiens (moved to Fredericton)

- World League of American Football

- Montreal Machine (defunct)

- Canadian-American League

- Quebec Braves/Alouettes/Athletics (defunct)

- Trois-Rivières Royals (defunct)

- International Hockey League

- Quebec Rafales (defunct)

- Canadian soccer League (1987-1992)

- Montreal Supra (defunct)

- National Lacrosse League

- Montreal Express (folded, rights to team sold, eventually became the Minnesota Swarm)

- National Lacrosse League (1974–1975)

- Quebec Caribous (defunct)

- National Women's Hockey League

- Montreal Axion

- Quebec Avalanche

- North American Soccer League (1968-1984)

- Montreal Manic (defunct)

- Roller Hockey International

- Montreal Roadrunners

Symbols

In 1939, the government of Quebec unilaterally ratified its coat of arms to reflect Quebec's political history: French rule (gold lily on blue background), British rule (lion on red background) and Canadian rule (maple leaves) and with Quebec's motto below "Je me souviens".[69] Je me souviens ("I remember") was first carved under the coat of arms of Quebec's Parliament Building façade in 1883. It is an official part of the coat of arms and has been the official license plate motto since 1978, replacing "La belle province" (the beautiful province). The expression La belle province is still used mostly in tourism as a nickname for the province.

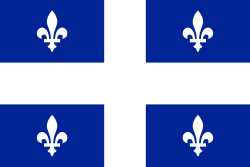

The fleur-de-lis, the ancient symbol of the French monarchy, first arrived on the shores of the Gaspésie in 1534 with Jacques Cartier on his first voyage. In 1900, Quebec finally sought to have its own uniquely designed flag. By 1903, the parent of today's flag had taken shape, known as the "Fleurdelisé". The flag in its present form with its 4 white "fleur-de-lis" lilies on a blue background with a white cross replaced the Union Jack on Quebec's Parliament Building on January 21, 1948.

Other official symbols

- The floral emblem of Quebec is the Iris versicolor.[7]

- Since 1987 the avian emblem of Quebec has been the snowy owl.[7]

- An official tree, the yellow birch (bouleau jaune, merisier), symbolises the importance Quebecers give to the forests. The tree is known for the variety of its uses and commercial value, as well as its autumn colours.[7]

In 1998 the Montreal Insectarium sponsored a poll to choose an official insect. The White Admiral butterfly (Limenitis arthemis)[70] won with 32 % of the 230 660 votes against the Spotted lady beetle (Coleomegilla maculata lengi), the Ebony Jewelwing damselfly (Calopteryx maculata), a species of bumble bee (Bombus impatiens) and the six-spotted tiger beetle (Cicindela sexguttata sexguttata).

Fête nationale

In 1977, the Quebec Parliament declared June 24 to be Quebec's National Holiday. Historically June 24 was a holiday honouring French Canada's patron saint, St. John the Baptist, which is why it is commonly known as La Saint-Jean-Baptiste (often shortened to La St-Jean). On this day, the song "Gens du pays" by Gilles Vigneault is often heard and commonly regarded as Quebec's unofficial anthem.

See also

- Culture of Quebec

- History of Quebec

Notes

- ↑ Titre I – Le statut de la langue française – Chapitre I – La langue officielle du Québec.

- ↑ The term Québécois (feminine: Québécoise), which is usually reserved for francophone Quebecers, may be rendered in English without both e-acute (é): Quebecois (fem.: Quebecoise). (Oxford Guide to Canadian English Usage; ISBN 0-19-541619-8; p. 335).

- ↑ It is sometimes spelled "Quebecker"

- ↑ "Canada's population estimates: Table 2 Quarterly demographic estimates". Statcan.gc.ca. 2010-06-28. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/daily-quotidien/100628/t100628a2-eng.htm. Retrieved 2010-06-30.

- ↑ Gross domestic product, expenditure-based, by province and territory.

- ↑ "Addressing Guidelines". Canada Post. http://www.canadapost.ca/tools/pg/manual/PGaddress-e.asp#1380608.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 "National Flag and Emblems". Services Québec. http://www.gouv.qc.ca/portail/quebec/pgs/commun/portrait?id=portrait.drapeau&lang=en. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ According to the Canadian government, Québec (with the acute accent) is the official name in French and Quebec (without the accent) is the province's official name in English; the name is one of 81 locales of pan-Canadian significance with official forms in both languages. In this system, the official name of the capital is Québec in both official languages. The Quebec government renders both names as Québec in both languages.

- ↑ "Quebec." Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed. 2003. (ISBN 0-87779-809-5) New York: Merriam-Webster, Inc."

- ↑ Quebec is located in the eastern part of Canada, but is also historically and politically considered to be part of Central Canada (with Ontario).

- ↑ "Community highlights for Nord-du-Québec". Statistics Canada. 2006. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/profiles/community/Details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CD&Code1=2499&Geo2=PR&Code2=24&Data=Count&SearchText=Nord-du-Qu%E9bec&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=24&B1=All&Custom=. Retrieved 2008-12-01.

- ↑ "Routine Proceedings: The Québécois". Hansard of 39th Parliament, 1st Session; No. 087. Parliament of Canada. 2006-11-22. http://www2.parl.gc.ca/HousePublications/Publication.aspx?Language=E&Mode=1&Parl=39&Ses=1&DocId=2528725#SOB-1788846. Retrieved 2008-04-30.

- ↑ "House of Commons passes Quebec nation motion". CTV News. 2006-11-27. http://www.ctv.ca/servlet/ArticleNews/story/CTVNews/20061127/quebec_motion_061127?s_name=&no_ads=. Retrieved 2009-10-03. "The motion is largely seen as a symbolic recognition of the Québécois nation."

- ↑ Poitras, François (2004-01). "Regional Economies Special Report Micro-Economic Policy Analysis" (PDF). Industry Canada. http://www.ic.gc.ca/epic/site/eas-aes.nsf/vwapj/srreo200401e.PDF/$FILE/srreo200401e.PDF. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ↑ Afable, Patricia O. and Madison S. Beeler (1996). "Place Names". In "Languages", ed. Ives Goddard. Vol. 17 of Handbook of North American Indians, ed. William C. Sturtevant. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, p. 191.

- ↑ "Canada: A People's History – The birth of Quebec". Canadian Broadcast Corporation. 2001. http://history.cbc.ca/history/?MIval=EpContent.html&series_id=1&episode_id=2&chapter_id=4&page_id=4&lang=E. Retrieved 2006-08-26.

- ↑ From Treaty of Paris, 1763: "His Most Christian Majesty cedes and guaranties to his said Britannick Majesty, in full right, Canada, with all its dependencies, as well as the island of Cape Breton, and all the other islands and coasts in the gulph and river of St. Lawrence, and in general, every thing that depends on the said countries, lands, islands, and coasts, with the sovereignty, property, possession, and all rights acquired by treaty, or otherwise, which the Most Christian King and the Crown of France have had till now over the said countries, lands, islands, places, coasts, and their inhabitants".

- ↑ Library of the Parliament of Canada, Parl.gc.ca

- ↑ "Saguenay-St. Lawrence National Park". http://www.greatcanadianparks.com/quebec/saguenp/index.htm.

- ↑ "Mingan Archipelago National Park Reserve of Canada". Parks Canada. 2008-05-02. http://www.pc.gc.ca/pn-np/qc/mingan/index_e.asp. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ↑ "Borderlands / St. Lawrence Lowlands". The Atlas of Canada. Natural Resources Canada. 2006-10-25. http://atlas.nrcan.gc.ca/site/english/maps/environment/land/st_lawrence_lowlands.html. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ Elson, J.A.. "St Lawrence Lowland". Canadian Encyclopedia. Historica Foundation. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0007093. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ Lasalle, Pierre; Robert J. Rogerson. "Champlain Sea work = Canadian Encyclopedia". Historica Foundation. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0001507. Retrieved 2008-04-28.

- ↑ Basques, The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ↑ "Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online". http://www.biographi.ca/009004-119.01-e.php?BioId=34229.

- ↑ Estimated population of Canada, 1605 to present.

- ↑ SWiSH v2.0. "Les Patriotes de 1837@1838". Cgi2.cvm.qc.ca. http://cgi2.cvm.qc.ca/glaporte/1837.pl?cat=ptype&cherche=DOCUMENT. Retrieved 2010-02-21.

- ↑ Declaration of Independence of Lower Canada. Retrieved on 2010-02-21.

- ↑ Front de libération du Québec from the Canadian Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Tetley, William (2006). "Appendix D: The Crisis per se (in chronological order - October 5, 1970 to December 29, 1970) - English text". The October Crisis, 1970: An Insider's View. McGill-Queen's University Press. ISBN 9780773531185. OCLC 300346822. Archived from the original on June 23, 2009. http://www.mcgill.ca/files/maritimelaw/D.doc. Retrieved June 23, 2009.

- ↑ "Le Protecteur du citoyen". Protecteurducitoyen.qc.ca. http://www.protecteurducitoyen.qc.ca/en/index.asp. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

- ↑ Susan Munroe, October Crisis Timeline, Canada Online. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ↑ Sheppard, Robert. "Constitution, Patriation of". The Canadian Encyclopedia. http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.com/index.cfm?PgNm=TCE&Params=A1ARTA0001869. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ↑ "The Calgary Declaration: Premiers' Meeting". September 14, 1997. http://www.exec.gov.nl.ca/currentevents/unity/unityr1.htm.

- ↑ Résolution de l'Assemblée Nationale du Québec, October 30, 2003PDF (95.4 KB)

- ↑ Hansard; 39th Parliament, 1st Session; No. 087; November 27, 2006.

- ↑ Galloway, Gloria; Curry, Bill; Dobrota, Alex (November 28, 2006). "'Nation' motion passes, but costs Harper". Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20061128.wnation28/BNStory/National/home.

- ↑ Bonoguore, Tenille; Sallot, Jeff; (November 27, 2006). "Harper's Quebec motion passes easily". Globe and Mail. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/servlet/story/RTGAM.20061127.wchong1127/BNStory/National.

- ↑ "Debate: The motions on the Québécois nation". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2006-11-24. http://www.cbc.ca/news/background/parliament39/motion-quebecnation.html. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ↑ "Who's a Québécois? Harper isn't sure". Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. 2006-12-19. http://www.cbc.ca/canada/story/2006/12/19/harper-motion.html?ref=rss. Retrieved 2006-12-21.

- ↑ Le premier ministre énonce sa vision et crée une commission spéciale d’étude (8 février 2007) Qc.ca. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Ibid. Free translation.

- ↑ Qc.ca. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- ↑ Qc.ca. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Qc.ca. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ Qc.ca. Retrieved November 6, 2008.

- ↑ "Fertility rate of women Quebecers over 1.7 children per woman for the first time since 1976". April 14, 2009. http://www.stat.gouv.qc.ca/salle-presse/communiq/2009/avril/avril0914_an.htm.

- ↑ Un peu plus de naissances et de décès au Québec en 2007 : Portail Québec : site officiel du gouvernement du Québec

- ↑ "Population urban and rural, by province and territory". http://www40.statcan.ca/l01/cst01/demo62f.htm.

- ↑ "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, 2006 and 2001 censuses - 100% data". http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/popdwell/Table.cfm?T=101.

- ↑ Ethnic origins, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories - 20% sample data.

- ↑ Aboriginal Population Profile (2006 Census).

- ↑ Visible minority groups, 2006 counts, for Canada, provinces and territories - 20% sample data.

- ↑ Selected Religions, for Canada, Provinces and Territories.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 "Population by mother tongue and age groups, percentage distribution (2006), for Canada, provinces and territories, and census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations – 20% sample data". Statistics Canada. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/highlights/language/Table401.cfm. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Charter of the French Language

- ↑ "Att. Gen. of Quebec v. Blaikie et al., 1979 CanLII 21 (S.C.C.)". Canadian Legal Information Institute. http://www.canlii.org/en/ca/scc/doc/1979/1979canlii21/1979canlii21.html. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ↑ "A.G. (Quebec) v. Blaikie et al., [1981 1 S.C.R. 312"]. http://www.canlii.org/eliisa/highlight.do?language=en&searchTitle=Federal&path=/en/ca/scc/doc/1981/1981canlii14/1981canlii14.html.

- ↑ "Population by mother tongue and age groups, percentage distribution (2006), for Canada, provinces and territories – 20% sample data". Ottawa: Statistics Canada. December 2007. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/highlights/language/Table401.cfm. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ↑ "Population by language spoken most often at home and age groups, percentage distribution (2006), for Canada, provinces and territories, and census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations – 20% sample data". Ottawa: Statistics Canada. December 2007. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/highlights/language/Table402.cfm. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ↑ Greater Montreal Community Development Initiative (GMCDI) (April 2007). "Demographics and the Long-term Development of the English-speaking Communities of the Greater Montreal Region" (PDF). Montreal: The Quebec Community Groups Network. http://www.qcgn.ca/files/QCGN/a20070409_demographics.pdf. Retrieved 2007-04-18.

- ↑ "Language". Statistics Canada. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/profiles/community/Details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=PR&Code1=24&Geo2=PR&Code2=01&Data=Count&SearchText=Quebec&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=Language&Custom=. Retrieved 2007-12-04.

- ↑ "Language". Statistics Canada. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/profiles/community/Details/Page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CD&Code1=2466&Geo2=PR&Code2=24&Data=Count&SearchText=Montreal&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=Language&Custom=. Retrieved 2008-02-18.

- ↑ Detailed Mother Tongue (148), Single and Multiple Language Responses (3) and Sex (3) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census – 20% Sample Data. 2007. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/topics/RetrieveProductTable.cfm?ALEVEL=3&APATH=3&CATNO=&DETAIL=0&DIM=&DS=99&FL=0&FREE=0&GAL=0&GC=99&GK=NA&GRP=1&IPS=&METH=0&ORDER=1&PID=89186&PTYPE=88971&RL=0&S=1&ShowAll=No&StartRow=1&SUB=701&Temporal=2006&Theme=70&VID=0&VNAMEE=&VNAMEF=&GID=837953.

- ↑ Ed Crooks (6 July 2009). "Using Russian hydro to power China". Financial Times. http://blogs.ft.com/energy-source/2009/07/06/using-russian-hydro-to-power-china/. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ↑ PennWell (29 October 2009). "Hydro-Quebec agrees to buy NB Power for C$4.75 billion". HydroWorld. http://www.hydroworld.com/index/display/article-display/9416279805/articles/hrhrw/News-2/2009/10/hydro-quebec-agrees.html. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ The Console Wars: Montreal and the Revolution | Xbox 360, Playstation 3 PS3, Revolution.

- ↑ Statistics Canada. "Population and dwelling counts, for Canada, provinces and territories, census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations, 2006 and 2001 censuses - 100% data". 2006 Census. Statistics Canada. http://www12.statcan.ca/english/census06/data/popdwell/Table.cfm?T=202&PR=24&S=0&O=A&RPP=50. Retrieved 2008-11-06.

- ↑ Justice Québec – Drapeauet et symboles nationaux (French)

- ↑ "Amiral [Toile des insectes du Québec - Insectarium ]". .ville.montreal.qc.ca. 2001-05-29. http://www2.ville.montreal.qc.ca/insectarium/toile/info_insectes/fiches/fic_fiche08_amiral.htm. Retrieved 2010-07-11.

References

- Armony, Victor (2007). Le Québec expliqué aux immigrants. Montréal, VLB Éditeur, 208 pages, ISBN 978-2-89005-985-6.

- Lacoursière, Jacques, Jean Provencher et Denis Vaugeois (2000). Canada-Québec 1534–2000. Sillery, Septentrion. 591 pages, (ISBN 2-89448-156-X)

- Jacques Lacoursière, Histoire du Québec, Des origines à nos jours, Édition Nouveau Monde, 2005, ISBN 2-84736-113-8

- Linteau, Paul-André (1989). Histoire du Québec contemporain – Volume 1; De la Confédération à la crise (1867–1929), Histoire, coll. «Boréal Compact» n° 14, 758 pages, (ISBN 2-89052-297-8)

- Linteau, Paul-André (1989). Histoire du Québec contemporain – Volume 2; Le Québec depuis 1930, Histoire, coll. «Boréal Compact» n° 15, 834 pages, (ISBN 2-89052-298-5)

- Québec. Institut de la statistique du Québec (2007). Le Québec chiffres en main, édition 2007[pdf]. 56 pages, (ISBN 2-550-49444-7)

- Venne, Michel (dir.) (2006). L'annuaire du Québec 2007. Montréal, Fides. 455 pages, (ISBN 2-7621-2746-7)

External links

- (English) Government of Quebec

- Quebec at the Open Directory Project

- (English) Discover the Quebec in pictures, photos

- (English) Bonjour Québec, Quebec government official tourist site

- (English) Bill 101

- (English) CBC Digital Archives – Quebec Elections: 1960–1998

- (French) Agora, online encyclopaedia from Quebec

- (English) An article on the province of Quebec from The Canadian Encyclopedia

- (English) Quebec travel guide from Wikitravel

- History

- (English) Quebec History, online encyclopaedia made by Marianopolis College

- (English) The 1837–1838 Rebellion in Lower Canada, Images from the McCord Museum's collections

- (French) Bibliothèque nationales du Québec Map Collection, 5,000 digitized maps

- (English) Haldimand Collection, documents in relation with Province of Quebec during the American War of Independence (1775–1784)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||